Abstract

Background

In the UK military, adjustment disorder (AjD) is reported as one of the most diagnosed mental disorders, alongside depression, in personnel presenting to mental health services. Despite this, little is understood about what may predict AjD, common treatment or outcomes for this population.

Aim

The systematic review aimed to summarise existing research for AjD in Armed Forces (AF) populations, including prevalence and risk factors, and to outline clinical and occupational outcomes.

Method

A literature search was conducted in December 2020 to identify research that investigated AjD within an AF population (serving or veteran) following the PRISMA guidelines.

Results

Eighty-three studies were included in the review. The AjD prevalence estimates in AF populations with a mental disorder was considerably higher for serving AF personnel (34.9%) compared to veterans (12.8%). Childhood adversities were identified as a risk factor for AjD. AjD was found to increase the risk of suicidal ideation, with one study reporting a risk ratio of 4.70 (95% Confidence Interval: 3.50–6.20). Talking therapies were the most common treatment for AjD, however none reported on treatment effectiveness.

Conclusion

This review found that AjD was commonly reported across international AF. Despite heterogeneity in the results, the review identifies several literature gaps.

Background

Armed Forces (AF) personnel are often required to work in challenging environments which may impact their physical and psychological health. Research has identified several occupational stressors which may increase the risk of psychological ill-health including deployment, combat experience, lack of leadership support and role conflict (Brooks & Greenberg, Citation2018; Campbell & Nobel, Citation2009). In 2021, Defence Statistics data indicated that 1 in 10 UK AF personnel were seen by an AF clinician for mental health reasons (Ministry of Defence, Citation2021). Of those seen by a clinician, 33% were initially found to be experiencing adjustment disorder (AjD). Of the whole AF population AjD (0.6%) was as frequently diagnosed as depression (0.6%) and seen more frequently than Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (0.2%) and substance misuse (0.1%).

The tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) identifies symptoms of AjD as: anxiety, depressed mood and worry, and an inability to cope (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation1993). The main distinction between AjD and other mental disorders is the exposure to a specific external stressor which triggers the symptomology and significantly impacts the individual’s ability to cope (Carta et al., Citation2009; Casey, Citation2009; Kazlauskas et al., Citation2018; Reid, Citation2018). The exact nature of the external stressor can vary from a serious accident (Kühn et al., Citation2006), to a bereavement (Greis, Citation2012), financial issues or a divorce (Glaesmer et al., Citation2015). Much like PTSD, individuals are aware of the stressor, which must be identified before making a diagnosis (Casey, Citation2009). However, there are differences which separate PTSD from AjD (Zelviene & Kazlauskas, Citation2018). The stressful event for PTSD can be unexpected, traumatic, stressful or life-threatening event where the individual may have episodes of reliving the event (i.e. flashbacks) (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation1993). In comparison, for AjD the individual’s response to a significant life event needs to exceed a “normal” reaction if others were experiencing the same event (Gradus et al., Citation2010) and symptoms can be directly linked to the event (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation1993).

Despite AjD’s prevalence within the AF population, little research has been conducted into the disorder. This contrasts the substantial body of literature exploring risk factors, outcomes, and treatment for other mental disorders such as depression and PTSD. Research beyond the UK AF has been conducted to explore potential AjD risk factors, however, all report mixed findings (Chen et al., Citation2011; Haskell et al., Citation2011; Yaseen, Citation2017). Yaseen (Citation2017) identified that individuals who had a low educational level, who were single, between 15 and 25 years old or a student had an increased risk of AjD. However, it is unclear whether this risk profile would accurately translate to an AF population. Further, literature identifies talking therapies and self-help tools are the most common treatment used for AjD in the general population (O’Donnell et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), however, there is no “gold-standard”. In fact, AjD remains one of the last disorders without treatment recommendations in The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines. Without an up-to-date literature summary for AjD in military populations there is a lack of clarity around typical symptom presentation and potential outcomes, increasing the difficulty to develop appropriate treatment pathways. Further, this hinders capacity to adjust military policies and practices appropriately; for example, should personnel with AjD be allowed access to firearms or deploy to conflict zones?

This review has three aims; (1) to summarise existing research conducted into AjD on AF populations (both AF personnel and veterans), (2) to outline any clinical or career implications that AjD may have for AF personnel and veterans and, (3) to identify areas needed for future explorative research to progress our understanding of AjD in AF population. The review includes eligible studies that report on the prevalence, risk and protective factors, symptomology, comorbidities, outcomes, and treatment pathways for AjD in AF populations.

Methods

Search strategy

The review followed guidelines outlined by PRISMA for conducting systematic reviews. Electronic databases were searched for eligible studies in December 2020. Databases included Embase, Medline, Global Health, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science and ASSIA. Database search terms included adjustment disorder (“adjustment disorder” OR “adjustment disorder with” OR F43.2 (ICD code)) AND military (“military” OR “armed forces” OR “army” OR “navy” OR “air force” OR “US coast guard” OR “marine*” OR “veteran*” OR “defence” OR “military personnel*” OR “soldier*” OR “ex-military” OR “ex-service” OR “new recruits” OR “conscript*”).

Eligibility criteria

The following review eligibility criteria were applied:

AjD was featured in the study results.

The study population included either AF personnel or veterans.

Participants had a formal diagnosis of AjD (i.e. given by a clinical professional), a self-reported diagnosis of AjD or were identified with a probable AjD using an AjD assessment measure (e.g. General Health Questionnaire).

The study was published in English (although studies could be conducted in any country).

The study was conducted from 1980 onwards (when the term “adjustment disorder” was first included in a diagnostic manual (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, 2013)).

The full-text version of the study is freely available or could be retrieved.

The study reported on peer-reviewed, empirical research thereby excluding:

Case reports

Literature reviews

Conference proceedings

PhD dissertations

Book chapters

Study protocols

This review uses the term “adjustment disorder” throughout which also includes sub-types that fall under the code F43.2 in the ICD-10 (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation1993). Qualitative and quantitative studies were included in the review.

Study quality

Quality assessment of all eligible AF personnel and veteran studies was primarily conducted by AM and reviewed by an independent reviewer (BC). The National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute’s Study Quality Assessment Tools (National Institutes of Health, Citation2014) were employed to assess study quality and any risk of bias. This tool examines specific study designs and assigns a score of either “good”, “fair” or “poor”. Those studies which were assigned a score of “poor” were excluded from the review. Where reviewers disagreed on scores, they were reassessed, and a consensus reached.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from included studies: author, publication date, location of study, population and participant characteristics, sample size, study methodology, AjD diagnosis, presence and characteristics of a control group, other mental disorders reported on, study design, and study outcomes.

Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006) was used to review and provide a summary of the included studies focusing on the following outcomes: AjD prevalence estimates, risk factors (including protective factors), symptoms, comorbidities, outcomes, and treatment. The review also included military Service subcategories for the study populations (i.e. serving, ex-serving, new recruits, conscripts) and separately examined the outcomes for veterans and AF personnel. There are discrepancies between the definition of a military veteran across different countries. In the United States (US), a veteran is defined as an AF personnel who has been deployed at least once, whereas in the UK a veteran is defined as an ex-serving Armed Forces personnel who served in any military Service as a regular or reserve for at least one day. Where applicable odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (AOR) or unadjusted odds ratio (UOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted for AjD risk and protective factors.

Results

Study sample

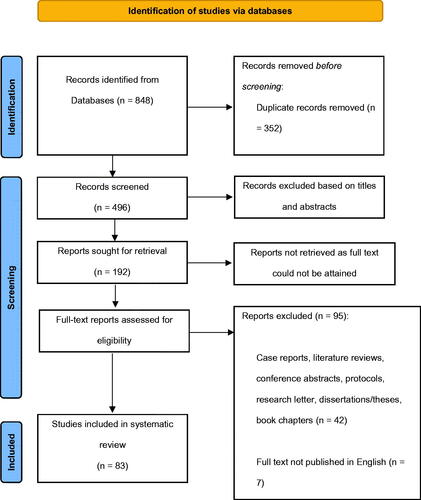

Eighty-three papers published between 1984 and 2020 were included in the final analysis (). Of the studies included, the majority (fifty-four studies) were conducted in the United States (US). Other study locations included the United Kingdom (UK), Turkey, Taiwan, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Israel, Korea, Sweden, and Sri Lanka. Sixty-seven studies used a cohort or observational design, and sixteen studies used a case-control design.

Figure 1. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the review’s study identification, screening, and inclusion process.

Fifty-three studies examined current AF personnel across military Services (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines and Coast Guard) (). Thirteen of these studies included personnel from two or more Service branches, twenty studies used only Army personnel in the sample and three studies were comprised of Air Force personnel only, the remaining studies did not specify which Service branch personnel served in. Thirty-one studies included both males and females in the study sample, with the frequency of male participants in each sample varying from 55% to 99%. Nineteen studies had a male-only sample, one study had a female-only sample, and two studies did not report the gender of participants. Three of the studies recruited only AF personnel but employed a longitudinal cohort study design meaning participants had often left the military (became veterans) at follow-up (Elonheimo et al., Citation2007; Gale et al., Citation2010; Ristkari et al., Citation2006).

Table 1. List of studies with AF personnel as the study population that was included in the final synthesis (n = 53).

Thirty of the studies included in the review sampled veteran participants, and all employed a cohort design (). As all thirty veteran studies were conducted in the US, the US definition of veteran will be employed. Most veteran studies included a study sample with both males and females (N = 24), although most participants in these studies were male (80–98%). Three studies included female veterans only and one study examined a male-only sample. All data for veteran studies were extracted from the US Veteran’s Affairs (VA) database.

Table 2. List of studies with military veteran participants as the study population that were included in the final synthesis (n = 30).

Adjustment disorder prevalence estimates

Forty-one of the 83 studies included in this review reported on the prevalence of AjD. As most studies were conducted in the US (N = 30), the AjD prevalence estimates reported in this review predominantly reflect the US military population. Over half of the studies included in this review reported on participants who were serving members of the AF at the time of data collection (n = 27).

Of the studies included in this review on AF personnel that reported AjD estimates (n = 27), twenty-two reported AjD as either the most reported, or second most reported mental disorder for AF personnel compared to other commonly assessed mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Only six studies reported AjD prevalence in a general AF population (including healthy AF personnel), with AjD prevalence ranging from 0.7 to 16.8% (M = 7.4%). In comparison, where AF personnel all had a mental disorder (n = 19), a mean prevalence of 34.9% was reported. Two studies reported AjD with depressed mood (Giotakos & Konstantakopoulos, Citation2002) and AjD with mixed disturbance of emotion and conduct (George et al., Citation2019) as the most common AjD subtypes.

For studies where the sample consisted of veterans with a mental disorder (n = 8), AjD prevalence ranged from 4.3 to 34% (M = 12.8%).

Risk factors and protective factors of adjustment disorder

Sixteen studies discussed risk and protective factors (n = 16). Most of these studies (n = 13) used an AF personnel sample, with four studies using veteran samples. It should be noted that there was a lack of homogeneity between studies of the risk factors investigated. Childhood adversity (n = 2) and personality traits (n = 2) were examined as pre-enlistment risk factors associated with AjD in later life. Specifically, increased parental abuse (Giotakos & Konstantakopoulos, Citation2002), reduced paternal care and protection (For-Wey et al., Citation2002), and increased neuroticism, alexithymia traits and decreased extroversion (Chen et al., Citation2011; For-Wey et al., Citation2002) were associated with AjD. However, both Chen et al. (Citation2011) and For-Wey et al. (Citation2002) were conducted in Taiwan where AF personnel were conscripts. Conscripted personnel have limited comparability to the UK AF which is voluntaryFootnote1 as military experiences and length of time served can differ. Haskell et al. (Citation2011) reported being female increased the risk of developing AjD (unadjusted OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.10–1.28) (adjusted OR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.14–1.34). Larson et al. (Citation2011) found that Army personnel were significantly more at risk of developing AjD, and Jones et al. (Citation2010) identified AjD as the most common mental disorder amongst deployed Army personnel.

Protective AjD factors were discussed (n = 4) including a higher level of education and increased IQFootnote2 (Gale et al., Citation2010), and AF personnel not deployed (Eick-Cost et al., Citation2017). Shrestha et al. (Citation2018) found that increased optimism, coping, adaptability, positive affect, spirituality, and life meaning, minimal catastrophic thinking, and reduced loneliness significantly reduced the likelihood of AjD or reduced the severity of AjD symptoms (Shrestha et al., Citation2018). Lindstrom et al. (Citation2006) found a negative association between combat support roles and adjustment disorder for female AF personnel compared to other military roles. However, the study does not clearly state which regiments were categorised as combat support roles and other occupational roles.

Adjustment disorder symptoms

Eight studies discussed symptoms of AjD. Two of the eight studies reported that most AF personnel experience moderate AjD symptoms (Doruk et al., Citation2008; Peterson et al., Citation2018). Other symptoms for AjD described by studies included dysphoria (Baker & Miller, Citation1991), non-replicative nightmaresFootnote3 (Freese et al., Citation2018) and somatic complaints (Ristkari et al., Citation2006). One study reported a significant increase in harm avoidance, and reduced self-directedness, cooperativeness, self-transcendence compared to healthy controls (Na et al., Citation2012). Oh et al. (Citation2018) found AF personnel with AjD had significantly higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T/S), Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90-R), and the Stress-Response Inventory (SRI) when compared to healthy controls.Footnote4 The study also found significant increased physical measures of stress (e.g., skin temperature), in comparison to healthy controls when performing a stress task. Giotakos and Konstantakopoulos (Citation2002) found from the SCL-90-R symptom checklist that somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic, anxiety and paranoid ideation all significantly were increased for AjD patients compared to healthy controls.

Comorbidities

Twenty-eight studies commented on AjD comorbidities. Of the veteran studies (n = 10), most commented on AjD comorbid with PTSD. When compared to other disorders, AjD had lower PTSD comorbidity (5.6%) when compared to depression (12.7%) and anxiety (14.9%) (Smith et al., Citation2016). Similar results were found in two other studies (Cohen et al., Citation2009; O’Donovan et al., Citation2015). Hefner and Rosenheck (Citation2019) reported a significantly higher risk for veterans to be diagnosed with AjD, if diagnosed with PTSD and two other mental disorders compared to PTSD alone (RR: 2.27). Babson et al. (Citation2018) found that significantly more insomniac case participants had an AjD compared to participants that did not report insomnia.

For AF personnel, Walter et al. (Citation2018) reported that AjD was the second most common mental disorder comorbid with PTSD (37%) with most common being depression (49%). Similar findings were found for AF personnel where comorbid PTSD and AjD were reported more frequently than AjD alone (Kozarić-Kovačić & Kocijan-Hercigonja, Citation2001) and personnel were significantly more likely to receive an AjD diagnosis if also diagnosed with PTSD.

Substance misuse was often identified as comorbid with AjD (n = 6); however, no studies reported significant associations. Ho and Rosenheck (Citation2018) did report an increased risk of being diagnosed with AjD for veterans if diagnosed with both cancer and a substance use disorder compared to just cancer alone (RR: 3.16). Doruk et al. (Citation2008) found similar results, reporting that 33.8% of AF personnel with AjD reported a history of substance misuse compared to controls (4.3%) (p < 0.0001). Doruk et al. (Citation2008) also reported more significant life events were experienced by AjD personnel with a history of substance misuse. Links between substance misuse, AjD and significant life events may be suggestive of harmful behaviours used as a coping mechanism for a precursor stressor.

Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were discussed in relation to AjD (n = 9) in AF personnel only. Seven studies reported a significant increase of suicidal ideation or attempts for AjD AF personnel compared to healthy controls, with one study reporting a risk ratio of 4.70 (95% CI: 3.50–6.20) (Bachynski et al., Citation2012). The remaining two studies found that suicide attempts were significantly associated with AjD (George et al., Citation2019; Kochanski-Ruscio et al., Citation2014). Kochanski-Ruscio et al. (Citation2014) study found over half of personnel with AjD (57%) had attempted suicide at least once and 48% had multiple attempts. Na et al. (Citation2013) found that significantly more personnel with AjD who had a history of suicidal ideation scored for alexithymia (an inability to identify one’s emotions) compared to personnel with AjD but without a history of suicide attempts and healthy controls.

Effect of adjustment disorder on military attrition

Six studies examined AjD and personnel attrition in the military, with most studies (n = 5) reporting higher rates of discharge or recommendation for separation from Service for AF personnel with AjD when compared to other mental disorders (Cigrang et al., Citation1998; Englert et al., Citation2003; Hansen-Schwartz et al., Citation2005; Jones et al., Citation2009; Niebuhr et al., Citation2006). Studies investigating early career personnel (i.e., basic trainees and conscripts) had higher discharge because of AjD (Cigrang et al., Citation1998; Englert et al., Citation2003; Hansen-Schwartz et al., Citation2005; Niebuhr et al., Citation2006). However, Britt et al. (Citation2018) found that AF personnel diagnosed with AjD were significantly more likely to be given a waiver to still be able to join the military compared to any other mental disorders.

Adjustment disorder treatment

Over half of the studies discussing help-seeking for treatment and treatment of AjD (n = 20) used veteran samples (n = 13). AjD had the strongest significant association with mental health outpatient care (Maguen et al., Citation2012) and an increased likelihood of help-seeking through veteran programmes when compared to other disorders (Etingen et al., Citation2019; Hoff & Rosenheck, Citation2000). Smith et al. (Citation2016) found that veterans received a diagnosis more frequently and quicker if AjD was comorbid with PTSD. Gerson et al. (Citation2004) reported the typical AjD duration for veterans as three months from stressor to diagnosis, and of patients receiving care at medical units, AjD was the most frequently diagnosed mental disorder after discharge.

In terms of treatment pathways, psychotherapy or counselling were the most frequently reported treatment options for AjD (Funderburk et al., Citation2011; Schmitz et al., Citation2012), behavioural modification training (e.g. substance abuse class, coping skills training) or a combination of psychotherapy and psychotropic medication (Schmitz et al., Citation2012; Smith et al., Citation2016). No studies investigated the effectiveness of AjD treatment in a AF population.

Discussion

Adjustment disorder prevalence estimates

From the review, the overall AjD prevalence estimate for AjD in both AF personnel and veterans is comparable, whilst there are notable differences in AjD prevalence estimates for those with a recognised mental disorder (AF personnel studies 35.7 vs. 12.8% for veterans).

Increased prevalence estimates of AjD amongst diagnosed AF personnel compared to veterans may suggest “stressors” that precursor AjD are more common in and specific to military life. Since experiences of military stressors are collectively shared amongst AF personnel (e.g., deployments), and stressors may be more persistent and ongoing (e.g., continuous deployment posts), meaning symptoms of AjD are slower to be relieved and more accepted as the “norm”. Although, most studies included in the review were conducted in the US and relevance to the UK AF population, and specifically the stressors experienced, are limited as military experiences can differ between the UK and the US (Sundin et al., Citation2014).

However, this does not explain why differences in AjD prevalence estimates between AF personnel and veterans are only apparent amongst those with mental disorders, and not within the wider community. It could be argued that higher AjD estimates are reported for AF personnel with mental disorders as AjD is often described as a less “severe” disorder compared to other mental disorders. For instance, the DSM-5 diagnostic criterion outlines that an AjD diagnosis can only be given once all other potential mental disorders are screened out (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Perhaps AjD diagnoses may not be as accurate as first thought. An AjD diagnosis may act as a “last case” diagnosis to offer, which in turn, increases prevalence. This is further supported by the results reported by Britt et al. (Citation2018) where personnel were more likely to receive a waiver for AjD compared to any other mental disorder, suggesting personnel are less likely to be discharged and retained in the military more easily. However, the restructuring of the diagnostic criterion for AjD in the new ICD-11 which will bring AjD more in line with other disorders such as depression and PTSD, may counteract this argument if prevalence estimates remain relatively similar.

Predictive factors of adjustment disorder

Pre-enlistment risk factors for AF personnel with AjD were discussed including personality traits and experiences of childhood adversity, specifically parental abuse, and neglect (Chen et al, Citation2011; For-wey et al., Citation2002; Giotakos & Konstantakopoulos, Citation2002). Childhood adversity is often associated with a multitude of mental disorders in AF personnel (Montgomery et al., Citation2013) including PTSD (Ozer et al., Citation2003), psychosis (Rössler et al., Citation2014), and anxiety (Sareen et al., Citation2013). Applewhite et al. (Citation2016) found that 85% of AF personnel help-seeking for a mental health issue reported at least one account of childhood adversity, with 40% reporting four or more accounts. However, links between childhood adversity and AjD require further exploration to unpick which features (e.g., abuse, neglect) put someone significantly more at risk later in adulthood. McLaughlin et al. (Citation2010) reported an increased risk for depression among individuals who had three or more accounts of childhood adversity and experienced a stressful life event in the past year (27.3%) compared to those without childhood adversity (14.8%). However, this study did not include explorations of association between AjD, childhood adversity and stressful life events, considering the importance of a stressful event in the AjD diagnostic criterion.

Despite the paucity of studies reporting military risk factors compared to non-military risk factors, the findings cannot be disregarded. Several studies highlighted that basic trainees or conscripts with AjD were often recommended for separation of duty or discharged (Cigrang et al., Citation1998; Englert et al., Citation2003; Hansen-Schwartz et al., Citation2005; Niebuhr et al., Citation2006). This suggests a potential association between new recruits, enlisting and AjD. However, research exploring new recruits and AjD is scarce and is recommended to explore which experiences specifically increase the risk of AjD for new recruits. The breadth of the review topic meant studies which investigated predictive factors of AjD contained a multitude of methodological practices, sample sizes and aims. As a result, a meta-analysis approach could not be employed which would provide a more scientific comparison of predictive factors for AjD between studies.

Suicidal ideation

Significant associations with suicidal ideation were discussed. Suicidal ideation is often described in general population studies as a common symptom for AjD (Carta et al., Citation2009; Fielden, Citation2012; Gradus et al., Citation2010). There is a surprising lack of inclusion of AjD in research which examines mental disorders and suicidal ideation in the general population and AF population, although some studies suggest that suicidal ideation can be as common in AjD as it is in depression (Polyakova et al., Citation1998). Despite suicidal ideation reoccurring in literature included in this review, current diagnostic manuals (ICD-10 and DSM-5) do not identify suicidal ideation as a symptom of AjD. It is clear the association between suicidal ideation and AjD requires serious consideration and research focus to emphasise suicidal risk as part of the AjD diagnostic criterion for clinical practice. Including suicidal risk in the AjD diagnostic description will not only help clinicians identify those at greater risk but also the correct treatment pathway. However, this could have significant implications on personnel attrition and increased military discharge for AjD personnel with suicidal ideation. Occupational outcomes such as this may be perceived as negative, but AjD patients would have the opportunity to recover away from military duties, resulting in a quicker recovery if the AjD precursor stressor is specific to military experience. It is recommended that future research lends itself to understanding the link between AjD and suicidal ideation and the impacts this may have on treatment options, recovery, and career outcomes.

Treatment

Treatment for AjD has previously been highlighted as an under-researched area for the general population (Carta et al., Citation2009) and even more so for AF population as highlighted in this review. Psychotherapy and self-help tools are the most frequently given treatment for AjD (O’Donnell et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Across all studies in the current review, no specific treatment stood out as most used and this reflects the lack of standardised clinical practice for AjD. For example, in the UK there is currently no guidance given by NICE to advise clinicians on AjD treatment. Research is needed to develop an evidence-based treatment framework for AjD and to contribute to the development of NICE guidelines.

Little is known about the effectiveness of AjD treatment and prognosis for AF populations. The reduction in evidence-based AjD treatment research could be explained due to the disorder’s relatively “short” symptom duration typically lasting up to six months (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation1993). Capturing participants when experiencing AjD symptoms provides a relatively short window, increasing research difficulty. Forming evidence-based guidelines for AjD treatment will help inform military healthcare policies to guarantee that patients are provided with the most effective care. This will benefit the patient as well as the military as an institution by preventing money and resources being wasted on AjD treatment for which the evidence on effectiveness is lacking. By guaranteeing the same standards of care and attention are provided to AjD as they are to other mental disorders, AjD awareness may increase and encourage help-seeking for AF personnel who experience AjD symptoms. Furthermore, without research into AjD prognosis, the implications of being diagnosed with AjD on clinical and career outcomes are still unknown. Future explorative research should follow AF personnel with AjD overtime to understand what implications AjD may have on career progression, recovery, and future mental disorder occurrence.

Conclusion

The systematic review aimed to summarise existing AjD research for AF populations, to outline clinical or career implications that AjD may have, and to identify areas needed for future exploration. Overall, AjD presented as a common mental disorder for AF populations across nations, and specifically for active AF personnel. Mixed risk and protective factors for AjD were identified, however, further investigations into military-specific risk factors is warranted as this research area was limited. Similarly, little research attention was afforded to exploring the implications AjD may have on clinical or career outcomes and the effectiveness of treatment, nevertheless the review findings suggest associations between AjD and increased military attrition which should be explored further.

Disclosure statement

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, Public Health England or the Department of Health and Social Care. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Conscripts are often of a younger age demographic, and this is reflected in the participant samples for both studies as the mean age was 22 years, compared to the average age of UK military personnel being 31 years (Ministry of Defence, Citation2020).

2 Gale et al. (Citation2010) reported that for each one-point decrease on the nine-point IQ scale, there was an increased risk of hospital admission for AjD (HR: 1.75, CI: 1.70–1.80).

3 Freese et al. (Citation2018) describe non-replicative nightmares, for the specific purpose of their study, as a nightmare that is not an exact replica of a traumatic event the patient has experienced but the nightmare is symbolic of a traumatic event and has associations with their diagnosis.

4 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), adjustment disorder often mirrors symptoms of other mental disorders such as depression and anxiety and symptoms for adjustment disorder include depressed mood, anxiety, and worry.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Applewhite, L., Arincorayan, D., & Adams, B. (2016). Exploring the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in soldiers seeking behavioral health care during a combat deployment. Military Medicine, 181(10), 1275–1280. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00460

- Apter, A., King, R. A., Bleich, A., Fluck, A., Kotler, M., & Kron, S. (2008). Fatal and non-fatal suicidal behavior in Israeli adolescent males. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110701798679.

- Babson, K. A., Wong, A. C., Morabito, D., & Kimerling, R. (2018). Insomnia symptoms among female veterans: Prevalence, risk factors, and the impact on psychosocial functioning and health care utilization. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(6), 931–939. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7154

- Bachynski, K. E., Canham-Chervak, M., Black, S. A., Dada, E. O., Millikan, A. M., & Jones, B. H. (2012). Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007–8. Injury Prevention, 18(6), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112.

- Baker, F. M., & Miller, C. L. (1991). Screening a skilled nursing home population for depression. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 4(4), 218–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/089198879100400407

- Balandiz, H., & Bolu, A. (2017). Forensic mental health evaluations of military personnel with traumatic life event, in a university hospital in Ankara, Turkey. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 51, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2017.07.018

- Beehler, G. P., Rodrigues, A. E., Mercurio-Riley, D., & Dunn, A. S. (2013). Primary care utilization among veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A retrospective chart review. Pain Medicine, 14(7), 1021–1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12126.

- Black, D. W., Blum, N., Letuchy, E., Doebbeling, C. C., Forman-Hoffman, V. L., & Doebbeling, B. N. (2006). Borderline personality disorder and traits in veterans: psychiatric comorbidity, healthcare utilization, and quality of life along a continuum of severity. CNS Spectrums, 11(9), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852900014772

- Blonigen, D. M., Macia, K. S., Bi, X., Suarez, P., Manfredi, L., & Wagner, T. H. (2017). Factors associated with emergency department use among veteran psychiatric patients. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 88(4), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9490-2

- Britt, T. W., McGhee, J. S., & Quattlebaum, M. D. (2018). Common mental disorders among US army aviation personnel: Prevalence and return to duty. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(12), 2173–2186. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22688

- Brooks, S. K., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Non-deployment factors affecting psychological wellbeing in military personnel: Literature review. Journal of Mental Health, 27(1), 80–90.

- Callegari, L. S., Zhao, X., Nelson, K. M., & Borrero, S. (2015). Contraceptive adherence among women veterans with mental illness and substance use disorder. Contraception, 91(5), 386–392.

- Callegari, L. S., Zhao, X., Nelson, K. M., Lehavot, K., Bradley, K. A., & Borrero, S. (2014). Associations of mental illness and substance use disorders with prescription contraception use among women veterans. Contraception, 90(1), 97–103.

- Campbell, D. J., & Nobel, O. B. Y. (2009). Occupational stressors in military service: A review and framework. Military Psychology, 21(sup2), S47–S67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995600903249149

- Carta, M. G., Balestrieri, M., Murru, A., & Hardoy, M. C. (2009). Adjustment Disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 5(1), 15–15.

- Casey, P. (2009). Adjustment disorder. CNS Drugs, 23(11), 927–938. https://doi.org/10.2165/11311000-000000000-00000

- Chang, H., Shiah, I., Chang, C., Chen, C., & Huang, S. (2008). A study of prematurely discharged from service and related factors in Taiwanese conscript soldiers with mental illness. Journal of Medical Sciences-Taipei, 28(1), 15.

- Chen, P.-F., Chen, C.-S., Chen, C.-C., & Lung, F.-W. (2011). Alexithymia as a screening index for male conscripts with adjustment disorder. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 82(2), 139–150.

- Cigrang, J. A., Carbone, E. G., Todd, S., & Fiedler, E. (1998). Mental health attrition from Air Force basic military training. Military Medicine, 163(12), 834–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/163.12.834.

- Cohen, B. E., Marmar, C., Ren, L., Bertenthal, D., & Seal, K. H. (2009). Association of cardiovascular risk factors with mental health diagnoses in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans using VA health care. JAMA, 302(5), 489–492.

- DiNapoli, E. A., Bramoweth, A. D., Cinna, C., & Kasckow, J. (2016). Sedative hypnotic use among veterans with a newly reported mental health disorder. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(8), 1391–1398.

- Dobscha, S. K., Delucchi, K., & Young, M. L. (1999). Adherence with referrals for outpatient follow-up from a VA psychiatric emergency room. Community Mental Health Journal, 35(5), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018786512676

- Doruk, A., Çelik, C., Özdemir, B., & Özşahin, A. (2008). Adjustment disorder and life events. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry, 9, 197–202.

- Ecker, A. H., Lang, B., Hogan, J., Cucciare, M. A., & Lindsay, J. (2020). Cannabis use disorder among veterans: Comorbidity and mental health treatment utilization. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 109, 46–49.

- Eick-Cost, A. A., Hu, Z., Rohrbeck, P., & Clark, L. L. (2017). Neuropsychiatric outcomes after mefloquine exposure among US military service members. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 96(1), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0390

- Elonheimo, H., Niemelä, S., Parkkola, K., Multimäki, P., Helenius, H., Nuutila, A.-M., & Sourander, A. (2007). Police-registered offenses and psychiatric disorders among young males. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(6), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0192-1.

- Englert, D. R., Hunter, C. L., & Sweeney, B. J. (2003). Mental health evaluations of U.S. Air Force basic military training and technical training students. Military Medicine, 168(11), 904–910. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/168.11.904.

- Etingen, B., Hogan, T. P., Martinez, R. N., Shimada, S., Stroupe, K., Nazi, K., Connolly, S. L., Lipschitz, J., Weaver, F. M., & Smith, B. (2019). How Do patients with mental health diagnoses use online patient portals? An observational analysis from the Veterans Health Administration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 46(5), 596–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00938-x.

- Fielden, J. S. (2012). Management of adjustment disorder in the deployed setting. Military Medicine, 177(9), 1022–1027. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-12-00057

- For-Wey, L., Fei-Yin, L., & Bih-Ching, S. (2002). The relationship between life adjustment and parental bonding in military personnel with adjustment disorder in Taiwan. Military Medicine, 167(8), 678–682.

- Freese, F., Wiese, M., Knaust, T., Schredl, M., Schulz, H., De Dassel, T., & Wittmann, L. (2018). Comparison of dominant nightmare types in patients with different mental disorders. International Journal of Dream Research, 11, 1–5.

- Funderburk, J. S., Sugarman, D. E., Labbe, A. K., Rodrigues, A., Maisto, S. A., & Nelson, B. (2011). Behavioral health interventions being implemented in a VA primary care system. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-011-9230-y.

- Gale, C. R., Batty, G. D., Tynelius, P., Deary, I. J., & Rasmussen, F. (2010). Intelligence in early adulthood and subsequent hospitalization for mental disorders. Epidemiology, 21(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0b013e3181c17da8.

- Garvey Wilson, A. L., Messer, S. C., & Hoge, C. W. (2009). U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(6), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0461-7.

- George, B. J., Ribeiro, S., Lee-Tauler, S. Y., Bond, A. E., Perera, K. U., Grammer, G., Weaver, J., & Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M. (2019). Demographic and clinical characteristics of military service members hospitalized following a suicide attempt versus suicide ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183274.

- Gerson, S., Mistry, R., Bastani, R., Blow, F., Gould, R., Llorente, M., Maxwell, A., Moye, J., Olsen, E., Rohrbaugh, R., Rosansky, J., Van Stone, W., & Jarvik, L. (2004). Symptoms of depression and anxiety (MHI) following acute medical/surgical hospitalization and post-discharge psychiatric diagnoses (DSM) in 839 geriatric US veterans. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(12), 1155–1167. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1217.

- Giotakos, O., & Konstantakopoulos, G. (2002). Parenting received in childhood and early separation anxiety in male conscripts with adjustment disorder. Military Medicine, 167(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/167.1.28.

- Glaesmer, H., Romppel, M., Brähler, E., Hinz, A., & Maercker, A. (2015). Adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11: Dimensionality and symptom differentiation. Psychiatry Research, 229(3), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.010

- Goldstein, G., Luther, J. F., Haas, G. L., Appelt, C. J., & Gordon, A. J. (2010). Factor structure and risk factors for the health status of homeless veterans. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 81(4), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-010-9140-4.

- Goodman, G. P., DeZee, K. J., Burks, R., Waterman, B. R., & Belmont, P. J. Jr, (2011). Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders sustained by a US Army brigade combat team during the Iraq War. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33(1), 51–57..

- Gould, M., Sharpley, J., & Greenberg, N. (2008). Patient characteristics and clinical activities at a British military department of community mental health. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32(3), 99–102. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.107.016337

- Gradus, J. L., Qin, P., Lincoln, A. K., Miller, M., Lawler, E., & Lash, T. L. (2010). The association between adjustment disorder diagnosed at psychiatric treatment facilities and completed suicide. Clinical Epidemiology, 2, 23–28.

- Greis, L. M. (2012). Adjustment disorder related to bereavement. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 8(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2011.08.018

- Gubata, M. E., Urban, N., Cowan, D. N., & Niebuhr, D. W. (2013). A prospective study of physical fitness, obesity, and the subsequent risk of mental disorders among healthy young adults in army training. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 75(1), 43–48.

- Hageman, I., Pinborg, A., & Andersen, H. S. (2008). Complaints of stress in young soldiers strongly predispose to psychiatric morbidity and mortality: Danish national cohort study with 10-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01129.x.

- Hansen-Schwartz, J., Kijne, B., Johnsen, A., & Andersen, H. S. (2005). The course of adjustment disorder in Danish male conscripts. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59(3), 193–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480510027661.

- Haskell, S. G., Mattocks, K., Goulet, J. L., Krebs, E. E., Skanderson, M., Leslie, D., Justice, A. C., Yano, E. M., & Brandt, C. (2011). The burden of illness in the first year home: Do male and female VA users differ in health conditions and healthcare utilization. Women’s Health Issues, 21(1), 92–97.

- Hefner, K., & Rosenheck, R. (2019). Multimorbidity among Veterans diagnosed with PTSD in the Veterans Health Administration nationally. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(2), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09632-5.

- Ho, P., & Rosenheck, R. (2018). Substance use disorder among current cancer patients: rates and correlates nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Psychosomatics, 59(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2018.01.003

- Hoff, R. A., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2000). Cross-system service use among psychiatric patients: Data from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 27(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02287807.

- Hunt, M. G., Cuddeback, G. S., Bromley, E., Bradford, D. W., & Hoff, R. A. (2019). Changing rates of mental health disorders among veterans treated in the VHA during troop drawdown, 2007–2013. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(7), 1120–1124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00437-1.

- Johnson-Lawrence, V. D., Szymanski, B. R., Zivin, K., McCarthy, J. F., Valenstein, M., & Pfeiffer, P. N. (2012). Primary care-mental health integration programs in the veterans affairs health system serve a different patient population than specialty mental health clinics. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 14(3), 27140. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.11m01286

- Jones, N., Fear, N., Greenberg, N., Hull, L., & Wessely, S. (2009). Occupational outcomes in soldiers hospitalized with mental health problems. Occupational Medicine, 59(7), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqp115

- Jones, N., Fear, N. T., Jones, M., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2010). Long-term military work outcomes in soldiers who become mental health casualties when deployed on operations. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 73(4), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2010.73.4.352

- Kazlauskas, E., Gegieckaite, G., Eimontas, J., Zelviene, P., & Maercker, A. (2018). A brief measure of the International Classification of Diseases-11 adjustment disorder: Investigation of psychometric properties in an adult help-seeking sample. Psychopathology, 51(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000484415

- Kelley, A. M., Bernhardt, K., McPherson, M., Persson, J. L., & Gaydos, S. J. (2020). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use among army aviators. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, 91(11), 897–900. https://doi.org/10.3357/amhp.5671.2020

- King, P. R., Vair, C. L., Wade, M., Gass, J., Wray, L. O., Kusche, A., Saludades, C., & Chang, J. (2015). Outpatient health care utilization in a sample of cognitively impaired veterans receiving care in VHA geriatric evaluation and management clinics. Psychological Services, 12(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000015

- Krishnan, R. R., Volow, M. R., Miller, P. P., & Carwile, S. T. (1984). Narcolepsy: preliminary retrospective study of psychiatric and psychosocial aspects. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 141(3), 428–431. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.141.3.428.

- Kochanski-Ruscio, K. M., Carreno-Ponce, J. T., DeYoung, K., Grammer, G., & Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M. (2014). Diagnostic and psychosocial differences in psychiatrically hospitalized military service members with single versus multiple suicide attempts. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 450–456.

- Koo, K. H., Hebenstreit, C. L., Madden, E., Seal, K. H., & Maguen, S. (2015). Race/ethnicity and gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Psychiatry Research, 229(3), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.08.013

- Kozarić-Kovačić, D., & Kocijan-Hercigonja, D. (2001). Assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbidity. Military Medicine, 166(8), 677–680.

- Kühn, M., Ehlert, U., Rumpf, H. J., Backhaus, J., Hohagen, F., & Broocks, A. (2006). Onset and maintenance of psychiatric disorders after serious accidents. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(8), 497–503.

- Larson, G. E., Hammer, P. S., Conway, T. L., Schmied, E. A., Galarneau, M. R., Konoske, P., J. A., Webb-Murphy, K. J., Schmitz, N., Edwards, & Johnson, D. C. (2011). Pre-deployment and in-theatre diagnoses of American military personnel serving in Iraq. Psychiatric Services, 62(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0015

- Lev-Tzion, R., Friedman, T., Schochat, T., Gazala, E., & Wohl, Y. (2007). Asthma and psychiatric disorders in male army recruits and soldiers. Israel Medical Association Journal, 9(5), 361.

- Li, H., Lin, Y., Chen, J., Wang, X., Wu, Q., Li, Q., & Chen, Z. (2017). Abnormal regional homogeneity and functional connectivity in adjustment disorder of new recruits: a resting-state fMRI study. Japanese Journal of Radiology, 35(4), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-017-0614-2

- Lindstrom, K. E., Smith, T. C., Wells, T. S., Wang, L. Z., Smith, B., Reed, R. J., Goldfinger, W. E., & Ryan, M. A. K. (2006). The mental health of U.S. military women in combat support occupations. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(2), 162–172.

- Maguen, S., Madden, E., Cohen, B. E., Bertenthal, D., & Seal, K. H. (2012). Time to treatment among veterans of conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan with psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatric Services, 63(12), 1206–1212. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200051

- Manos, G. H., Carlton, J. R., Kolm, P., Arguello, J. C., Alfonso, B. R., & Ho, A. P. (2002). Crisis intervention in a military population: A comparison of inpatient hospitalization and a day treatment program. Military Medicine, 167(10), 821–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/167.10.821

- Mathew, N., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2016). Prescription opioid use among seriously mentally ill veterans nationally in the Veterans Health Administration. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9939-4

- McDonald, S. D., Mickens, M. N., Goldberg-Looney, L. D., Mutchler, B. J., Ellwood, M. S., & Castillo, T. A. (2018). Mental disorder prevalence among U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients with spinal cord injuries. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 41(6), 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2017.1293868.

- McLaughlin, K. A., Conron, K. J., Koenen, K. C., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40(10), 1647–1658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992121

- Melcer, T., Walker, J., Sechriest, V. F., Bhatnagar, V., Richard, E., Perez, K., & Galarneau, M. (2019). A retrospective comparison of five‐year health outcomes following upper limb amputation and serious upper limb injury in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. The Journal of Injury, Function, and Rehabilitation, 11(6), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12047

- Melcer, T., Walker, G. J., Sechriest, V. F., Galarneau, M., Konoske, P., & Pyo, J. (2013). Short-term physical and mental health outcomes for combat amputee and nonamputee extremity injury patients. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 27(2), e31–e37.

- Mergui, J., Raveh-Brawer, D., Ben-Ishai, M., Prijs, S., Gropp, C., Barash, I., Golmard, J. L., & Jaworowski, S. (2018). Psychopathology of Israeli soldiers presenting to a general hospital emergency department: Lessons for the attending physician and psychiatrist. Israel Medical Association Journal, 20(9), 561–566.

- Ministry of Defence. (2020). UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 October 2020. - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- Ministry of Defence. (2021). UK Armed Forces mental health annual summary & trend over time, 2007/8–2020/21. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1083916/MH_Annual_Report_2021-22.pdf

- Montgomery, A. E., Cutuli, J. J., Evans-Chase, M., Treglia, D., & Culhane, D. P. (2013). Relationship among adverse childhood experiences, history of active military service, and adult outcomes: Homelessness, mental health, and physical health. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S262–S268. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301474

- Morgan, M. A., Kelber, M. S., O'Gallagher, K., Liu, X., Evatt, D. P., & Belsher, B. E. (2019). Discrepancies in diagnostic records of military service members with self-reported PTSD: Healthcare use and longitudinal symptom outcomes. General Hospital Psychiatry, 58, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.02.006.

- Na, K.-S., Oh, S.-J., Jung, H.-Y., Irene Lee, S., Kim, Y.-K., Han, C., Ko, Y.-H., Paik, J.-W., & Kim, S.-G. (2013). Alexithymia and low cooperativeness are associated with suicide attempts in male military personnel with adjustment disorder: A case–control study. Psychiatry Research, 205(3), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.027.

- Na, K. S., Oh, S. J., Jung, H. Y., Lee, S. I., Kim, Y. K., Han, C., Ko, Y. H., Paik, J. W., & Kim, S. G. (2012). Temperament and character of young male conscripts with adjustment disorder a case-control study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(11), 973–977.

- National Institutes of Health. (2014). Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Neal, L. A., Kiernan, M., Hill, D., McManus, F., & Turner, M. A. (2003). Management of mental illness by the British Army. The British Journal of Psychiatry182(4), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.4.337

- Niebuhr, D. W., Powers, T. E., Krauss, M. R., Cuda, A. S., & Johnson, B. M. (2006). A review of initial entry training discharges at Fort Leonard Wood, MO, for accuracy of discharge classification type: Fiscal year 2003. Military Medicine, 171(11), 1142–1146. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed.171.11.1142

- O’Donnell, M. L., Agathos, J. A., Metcalf, O., Gibson, K., & Lau, W. (2019). Adjustment disorder: Current developments and future directions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142537

- O’Donnell, M. L., Metcalf, O., Watson, L., Phelps, A., & Varker, T. (2018). A systematic review of psychological and pharmacological treatments for adjustment disorder in adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(3), 321–331.

- O’Donovan, A., Cohen, B. E., Seal, K. H., Bertenthal, D., Margaretten, M., Nishimi, K., & Neylan, T. C. (2015). Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 77(4), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015.

- Oh, D. J., Lee, D. H., Kim, E. Y., Kim, W. J., & Baik, M. J. (2018). Altered autonomic reactivity in Korean military soldiers with adjustment disorder. Psychiatry Research, 261, 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.065.

- Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L., & Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52–73.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., & Mulrow, C. D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic reviews, 10(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Perera, H., Suveendran, T., & Mariestella, A. (2004). Profile of psychiatric disorders in the Sri Lanka Air Force and the outcome at 6 months. Military Medicine, 169(5), 396–399. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed.169.5.396

- Peterson, A. L., Hale, W. J., Baker, M. T., Cigrang, J. A., Moore, B. A., Straud, C. L., Dukes, S. F., Young-McCaughan, S., Gardner, C. L., Arant-Daigle, D., Pugh, M. J., Williams Christians, I., & Mintz, J, STRONG STAR Consortium. (2018). Psychiatric aeromedical evacuations of deployed active-duty U.S. military personnel during operations enduring freedom, Iraqi freedom, and new dawn. Military Medicine, 183(11–12), e649–e658. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy188

- Polyakova, I., Knobler, H. Y., Ambrumova, A., & Lerner, V. (1998). Characteristics of suicidal attempts in major depression versus adjustment reactions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 47(1–3), 159–167.

- Prier, R. E., McNeil, J. G., & Burge, J. R. (1991). Inpatient psychiatric morbidity of HIV-infected soldiers. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 42(6), 619–623. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.42.6.619.

- Reid, G. (2018). Adjustment disorder: An occupational perspective (with particular focus on the military). Adjustment Disorders, 173, 173-188.

- Ristkari, T., Sourander, A., Ronning, J., & Helenius, H. (2006). Self-reported psychopathology, adaptive functioning and sense of coherence, and psychiatric diagnosis among young men. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(7), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0059-x

- Rössler, W., Hengartner, M. P., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Haker, H., & Angst, J. (2014). Impact of childhood adversity on the onset and course of subclinical psychosis symptoms–results from a 30-year prospective community study. Schizophrenia Research, 153(1–3), 189–195.

- Sareen, J., Henriksen, C. A., Bolton, S. L., Afifi, T. O., Stein, M. B., & Asmundson, G. J. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences in relation to mood and anxiety disorders in a population-based sample of active military personnel. Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171200102X

- Schmitz, K. J., Schmied, E. A., Webb-Murphy, J. A., Hammer, P. S., Larson, G. E., Conway, T. L., Galarneau, M. R., Boucher, W. C., Edwards, N. K., & Johnson, D. C. (2012). Psychiatric diagnoses and treatment of U.S. military personnel while deployed to Iraq. Military Medicine, 177(4), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-11-00294.

- Shelef, L., Kaminsky, D., Carmon, M., Kedem, R., Bonne, O., Mann, J. J., & Fruchter, E. (2015). Risk factors for suicide attempt among Israeli Defence Forces soldiers: A retrospective case-control study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.016

- Shrestha, A., Cornum, B. R., Vie, L. L., Scheier, L. M., Lester, M. P. B., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). Protective effects of psychological strengths against psychiatric disorders among soldiers. Military Medicine, 183(suppl_1), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx189.

- Smith, N. B., Cook, J. M., Pietrzak, R., Hoff, R., & Harpaz-Rotem, I. (2016). Mental health treatment for older veterans newly diagnosed with PTSD: A national investigation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(3), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.02.001.

- Sundin, J., Herrell, R. K., Hoge, C. W., Fear, N. T., Adler, A. B., Greenberg, N., Riviere, L. A., Thomas, J. L., Wessely, S., & Bliese, P. D. (2014). Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(3), 200–207.

- Tsai, J., Rosenheck, R. A., Kasprow, W. J., & McGuire, J. F. (2014). Homelessness in a national sample of incarcerated veterans in state and federal prisons. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41(3), 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0483-7.

- Turner, M. A., Kiernan, M. D., McKechanie, A. G., Finch, P. J. C., McManus, F. B., & Neal, L. A. (2005). Acute military psychiatric casualties from the war in Iraq. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(6), 476–479. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.6.476

- Walter, K. H., Levine, J. A., Highfill-McRoy, R. M., Navarro, M., & Thomsen, C. J. (2018). Prevalence of Posttraumatic stress disorder and psychological comorbidities among U.S. active-duty service members, 2006-2013. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(6), 837–844. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22337

- West, J. C., Wilk, J. E., Duffy, F. F., Kuramoto, S. J., Rae, D. S., Moscicki, E. K., & Hoge, C. W. (2014). Mental health treatment access and quality in the Army: Survey of mental health clinicians. Journal of Psychiatric Practice®, 20(6), 448–459.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (1993). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Health Organization.

- Yacobi, A., Fruchter, E., Mann, J. J., & Shelef, L. (2013). Differentiating army suicide attempters from psychologically treated and untreated soldiers: A demographic, psychological and stress-reaction characterization. Journal of affective disorders, 150(2), 300–305.

- Yaseen, Y. A. (2017). Adjustment disorder: Prevalence, sociodemographic risk factors, and its subtypes in outpatient psychiatric clinic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 28, 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.012

- Zelviene, P., & Kazlauskas, E. (2018). Adjustment disorder: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 375–381.

- Zrihen, I., Ashkenazi, I., Lubin, G., & Magnezi, R. (2007). The cost of preventing stigma by hospitalizing soldiers in a general hospital instead of a psychiatric hospital. Military Medicine, 172(7), 686–689. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed.172.7.686.