Abstract

Background

Prior research on informal caregivers of people with schizophrenia (PWS) has primarily focused on parental caregivers. However, siblings also play an important role in the recovery process of PWS.

Aims

The aim of this study is to compare the coping profiles of family caregivers according to whether they are siblings or parents of the PWS.

Method

Parent and sibling caregivers (N = 181) completed the Family Coping Questionnaire (FCQ), which assessed their coping strategies.

Results

The results reveal that parents and siblings do not use the same coping strategies and styles. Three coping profiles were identified depending on the caregiver’s relationship with the PWS. Most parents displayed an undifferentiated profile (96.7%), while siblings were more heterogeneously distributed among the undifferentiated profile (58.3%), problem-focused profile (37.5%), and emotion and social support-focused profile (4.2%).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the coping capacities of family caregivers to deal with the illness of their sibling or child with schizophrenia are diverse and that it is important to differentiate among them. This would enable these caregivers to benefit from support that could be tailored to their specific needs.

Introduction

In recent years, family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia (PWS) have received increasing attention due to the deinstitutionalization movement (van der Meer & Wunderink, Citation2019). Family caregivers of PWS include members of nuclear families who provide support to people with chronic illness, such as parents, siblings, wives, and children (Kamil & Velligan, Citation2019). These caregivers constantly encounter their relatives’ symptomatology, including delusions, violent communication, disorganization symptoms or decreased interest in daily activities, which leads to social and professional dysfunctions that are characteristic of the disease (Porcelli et al., Citation2020). This situation generates intense stress, which such caregivers try to regulate through coping strategies (Kamil & Velligan, Citation2019). However, depending on whether these strategies are adapted to stressful situations, coping plays a crucial role in the physical and psychological health of individuals.

Stress and coping in family caregivers

The transactional model of stress, theorized by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), suggests that a situation can be stressful when it exceeds the individual’s resources. Consequently, coping corresponds to the cognitive and behavioral efforts deployed by the individual to try to reduce this stress. Coping can be understood in several ways, namely, through coping strategies, coping styles or coping profiles.

Coping strategies

Coping strategies refer to the different adjustment strategies that may be applied to deal with a particular situation, such as information seeking, resignation, and spiritual support. These strategies appear to be effective depending on whether the caregiver’s burden is reduced, unchanged or worsened (Grover et al., Citation2015; Magliano et al., Citation2000; Rexhaj et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2019). For example, disengagement or avoidance coping strategies used by family caregivers have been found to be positively correlated with their subjective burden (Kate et al., Citation2013; Ong et al., Citation2016). Conversely, information-seeking strategies are considered adaptive to reduce subjective burden (Grover et al., Citation2015; Kate et al., Citation2013).

Coping styles

Coping styles are a group of several coping strategies with similar characteristics. Three main coping styles emerge from the scientific literature about family caregivers of PWS: problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping and social support-focused coping (Plessis et al., Citation2018; Rexhaj et al., Citation2013). When the coping style is problem-focused, coping strategies consist of taking direct action to alleviate the problematic situation by seeking information, taking control, or weighing the pros and cons. This style appears to be most suitable for relatives of PWS (Grover et al., Citation2015; Rexhaj et al., Citation2016).

When the coping style is emotion-focused, coping strategies are used to regulate emotions by different means, such as positive reappraisal and distancing, and can be accompanied by compassion fatigue (Stamm, Citation2010). It is generally correlated with feelings of responsibility for the disease and leads to guilt and shame (Rexhaj et al., Citation2016), which suggests that it would not be suitable for family members of PWS.

The coping style centered on social support refers to coping strategies that involve seeking or maintaining social contacts, particularly with other relatives or health professionals (Kate et al., Citation2013). According to Grandón et al. (Citation2008), the more impaired the patient’s social functioning, the less this coping style is used by caregivers.

Coping profiles

A particular combination of several coping styles corresponds to a coping profile (Doron et al., Citation2015). In other words, to cope with a single situation, the same family caregiver may use several coping styles and this specific combination will define their coping profile (Scazufca & Kuipers, Citation1999). The majority of studies focus on demonstrating that individuals are prone to adopt one type of coping strategy over another instead of analyzing groups of individuals using several dimensions of coping styles simultaneously (Doron et al., Citation2015).

Coping strategies according to kinship

The majority of studies on family caregivers’ coping strategies do not consider kinship ties and their specificities (Guan et al., Citation2021; McFarlane, Citation2016; Meng et al., Citation2021; Onwumere et al., Citation2017). However, studies by Stanley and Balakrishnan (Citation2021a, Citation2021b) have shown differences in experiences between parents and spouses of PWS, suggesting an effect of kinship on the experience of caring. Moreover, sibling caregivers may experience relationships, problems and apprehensions that are quite distinct from those of parents, despite their limited importance in the existing PWS literature on family caregivers (Plessis et al., Citation2020b; Young et al., Citation2019). Indeed, the role of sibling caregiving is typically studied as relays after the death of their carer parents (Chadda, Citation2014; Dodge & Smith, Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2007; Stein et al., Citation2020). However, this approach neglects scenarios in which they may be called upon to provide support to their ailing relative before their parents die (Sin et al., Citation2016). Unlike parents, siblings have no obligation to care for their suffering relative. Therefore, siblings typically take on the role of carer out of family loyalty, responding to an implicit demand from the family group. The consequences often involve ambivalence in the initially egalitarian and reciprocal sibling relationship (Schmid et al., Citation2009). This ambivalence creates emotional distress that contributes to the deterioration of the psychological health of these siblings (Plessis et al., Citation2020; Yusuf & Nuhu, Citation2011).

The current study has two objectives. First, it aims to compare parental caregivers with sibling caregivers in terms of coping strategies and coping styles. Second, it seeks to explore coping profiles or specific combinations of coping styles (Eisenbarth, Citation2012). We hypothesize that we can distinguish between coping strategies, coping styles and coping profiles, depending on the nature of kinship to the PWS. Specifically, siblings tend to use more emotionally and socially supportive coping styles than parents, who adopt a more problem-oriented style. Similarly, the exploration of coping profiles should allow the identification of two distinct profiles depending on whether the caregivers are parents or siblings.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The sample of caregivers was obtained from French-speaking Switzerland and France (N = 204). It was composed of parent caregivers, sibling caregivers and other caregivers, including aunts and uncles, spouses and children. The sample of other caregivers (n = 23) was not homogeneous in their family ties and was therefore excluded from the study. Therefore, after excluding the sample of other caregivers, the sample for the study consisted of 181 family caregivers. We split this sample according to the family relationship of the caregivers with the patient (parent or sibling). The first group included 61 parental caregivers (70.49% female, Mage = 61.21, SD = 7.73) and the second group included 120 sibling caregivers (81.67% female, Mage = 37.94, SD = 13.71). There was no indication of whether the participants came from the same or different families as the experience of caring was unique to each family member.

Participants were recruited between 2012 and 2015 through family support associations. We contacted the presidents of associations consisting of relatives of people suffering from mental disorders in Switzerland (e.g. L'Ilot, Synapsespoir, etc.) and France (Unafam) in order to submit the study to their members. The project was presented online by the associations and meetings were organized to disseminate the relevant information. Participants could either pick up printed questionnaires with a prepaid envelope during the meetings or complete the questionnaire online using the electronic link sent by the associations’ presidents. No financial incentives were offered; all participants were volunteers.

A convenience sampling strategy was used for recruitment based on the following criteria: (1) being 18 years old or older, (2) living in Switzerland or France, (3) speaking French fluently, (4) being a family member of a PWS, and (5) considering themself as a caregiver for the family member suffering from schizophrenia.

Measures

Sociodemographic data

To identify the specificity of the family caregiver sample, a sociodemographic questionnaire was developed. Questions about the participants were related to age, gender and kinship with their ill relative. Questions about their ill relatives focused on the patients’ age, gender and the duration of illness.

The family coping questionnaire

The Family Coping Questionnaire (FCQ) is a self-report questionnaire developed by Magliano et al. (Citation1996) and validated in its French version by Plessis et al. (Citation2018). Family caregivers are required to respond to each item using a five-point Likert scale (1: never; 2: rarely; 3: sometimes; 4: very often; 5: not applicable). The FCQ is a clinical assessment tool suitable for families that focuses on specific ways of coping with the dysfunctions that characterize psychotic pathology. The French version of the FCQ includes 27 items that are used to provide a score for seven coping strategies.

These seven subscales can be clustered into three coping style factors (Plessis et al., Citation2018). The respondents can obtain a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 4 for each coping style. First, problem-focused coping includes five subscales that are representative of coping strategies, including the patients’ social involvement, positive communication, avoidance, information gathering and resignation. The patient’s social involvement subscale refers to the inclusion of the patient in social or familial activities, the positive communication subscale refers to the ability of the caregiver to communicate calmly and peacefully with the patient, the avoidance subscale refers to an effort by the caregiver to keep the patient away from them, the information gathering subscale refers to the caregiver’s ability to seek information about how to manage the patient’s illness, and the resignation subscale refers to the caregiver’s acceptance of the situation with no expectation of change. The avoidance and resignation subscales are negatively correlated with this coping style. Second, emotion-focused coping includes three subscales or coping strategies, such as coercion, avoidance and resignation. The coercion subscale refers to the caregiver’s anger and aggressiveness towards the patient and the avoidance and resignation subscales have been described previously. Third, social support-focused coping includes two subscales or coping strategies, namely, avoidance and social interest. The social interest subscale refers to the ability of family members to maintain an interest in their own social environment. The avoidance subscale has been described previously.

In this study, the French version of the FCQ showed good internal consistency (α = 0.851).

Statistical analysis

First, strategies and coping styles were compared based on kinship and gender using t-tests for independent samples. P values were corrected to account for multiple comparisons. Next, correlation analyses were performed for strategies and coping styles and the duration of illness/care and the age of the care recipient/caregiver, respectively.

Second, to assess the existence of specific coping profiles, latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted. The best solution was determined using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) coefficient, which balances the model fit with its complexity (Schwarz, Citation1978). For the sake of parsimony, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test and the parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test were used to verify whether a solution with one fewer class could present a similar degree of adjustment. Each coping style was entered separately for analysis. The relationship between the profiles and the caregiver’s familial position was estimated using a three-step latent class regression model with the Lanza method for categorical distal variables (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014; Lanza et al., Citation2013). To rule out the possibility that the association between class membership and familial position could only be explained by age, a logistic regression model was developed, with age and class membership as the independent variables and familial position as the dependent variable. Finally, to test whether the duration of illness differs among classes, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with class membership as the independent variable and duration of illness as the dependent variable. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM-SPSS 25 and Mplus version 8 software. All statistical tests were two-tailed and significance was determined at the 0.05 level.

Ethics approval

Information about the study was provided orally and/or in writing via an information letter to the participants. Written, free and informed consent was requested from all potential respondents before participation in the research. The research protocol received full authorization from the Ethics Committee for human-based research in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland and it conformed to the ethical standards defined by the local institutional review board and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2013).

Results

Sociodemographic data

A total of 181 family caregivers of PWS participated in this study. Among them, 120 were siblings and 61 were parents (see ). The majority of participants were female (70.49% parents and 81.67% siblings) and were caring for a male (74.41% parents and 86.67% siblings). In general, sibling caregivers were younger than parent caregivers (t = −13.91; p < 0.001). Siblings were on average 37 years old (SD = 13.71 years) and parents 60 years old (SD = 7.73 years) but they are caring for an older PWS than their parent (Mage of the PWS in the sibling sample = 37.69 years old; SD = 11.97; Mage of the PWS in the parent sample = 32.13 years old; SD = 10.70). The duration of the relative’s illness was longer in the sibling sample than in the parent sample (t = 2.20; p < 0.05).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of family caregivers (N = 181).

Coping strategies

The results are presented in . In terms of coping strategies used, parents and siblings differed in all dimensions, except for resignation and coercion. Parents relied more on information, positive communication and the patient’s social involvement than the siblings did. Conversely, siblings reported greater use of the social interest and avoidance coping strategies.

Table 2. Comparison of strategies and coping styles of parents and siblings.

shows the correlations between coping strategies and the caregiver’s age, the age of the care recipient and the duration of the illness.

Table 3. Pearson’s correlations between strategies and coping styles and sociodemographic variables.

Coping styles

In general, parents were more prone to adopt a problem-coping style than siblings. In contrast, siblings reported a higher use of emotion and social support-coping styles in comparison with parents (see ).

shows the correlations between coping styles and the caregiver’s age, the age of the care recipient and the duration of the illness (see ).

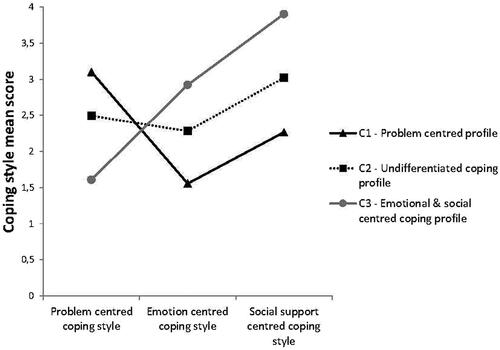

Coping profiles

Three coping profiles were identified based on the three-class model solution, which are shown in . The first class (C1), called the “problem-centered profile” (71.3% of the entire sample), consisted of caregivers with a profile oriented towards high problem-centered coping and low emotion and social support-centered coping. The second class (C2), called the “undifferentiated profile” (25.9% of the entire sample), consisted of caregivers with a relatively undifferentiated coping style. The third class (C3), called “emotional and social-centered coping profile” (2.8% of the entire sample), consisted of caregivers with low problem-centered and high emotion and social support coping styles.

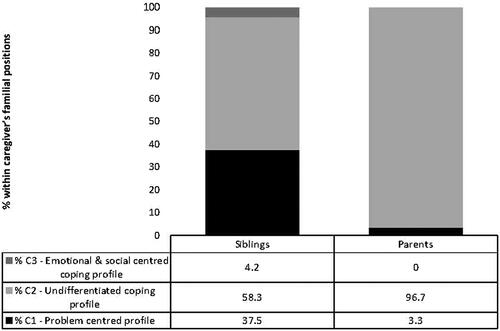

Membership in one of the three classes was associated with the caregiver’s familial positions (χ2(2) = 94.959, p < .001). shows the distribution of coping profiles according to family relationships. Parents were largely observed to exhibit an undifferentiated coping profile (96.7%). However, the siblings’ coping profiles appear to be more diverse than those of the parents. Of them, 58.3% were represented in the undifferentiated coping profile, 37.5% of them (versus 3.3% in the parents’ sample) displayed a problem coping profile, and 4.2% of the sample displayed an emotional coping profile (versus 0% in the parents’ sample).

Figure 2. Distribution (in percent) of coping profiles of family caregivers according to the relationship with the person suffering from schizophrenia.

The results of the logistic regression model suggested that family position could be predicted by coping profile membership (p < .001) even when age was considered. Caregivers with a problem-centered coping profile had been exposed to a shorter duration of illness than caregivers displaying the undifferentiated coping profile (p = .012).

Discussion

This study permitted us to compare the coping strategies of family caregivers of PWS according to their relationship with the ill relative, namely, siblings and parents. Our results suggest that coping behaviors are differentiated according to this relationship.

Coping strategies and styles

More specifically, our results suggest that parents display a greater tendency to adopt coping strategies that are focused on information, positive communication and patient involvement than siblings. Similarly, these parents also adopt the problem-focused coping style more than siblings. These results are consistent with the literature, which largely states that parental caregivers typically favor a problem-focused coping style (Grover et al., Citation2015).

Conversely, sibling caregivers tend to use coping strategies that focus more on avoidance and preservation of their social interests in comparison to the parents. These siblings also use a coping style that is more emotionally and socially supportive than parents. The preponderant use of avoidance strategies by siblings compared to parents could be an identity defense as they may avoid confronting certain situations (e.g. delusions) generated by the pathology of the suffering sibling. Unlike parents, siblings do not have generational barriers to defend themselves against identifications with the suffering sibling (Davtian, Citation2010). However, if avoidance initially constitutes a method of escape to reduce stress, this strategy ultimately represents a risk factor for the psychological health of individuals (Holahan et al., Citation2005). Emotional coping strategies, including coercion, avoidance and resignation, are associated with a significant burden on family caregivers of PWS (Kate et al., Citation2013) and may lead to negative perceptions regarding the recovery of the patients (Rexhaj et al., Citation2016).

Coping strategies and styles were also found to be related to the age and duration of illness of the PWS. These results suggest that the older the PWS, the more likely the caregivers are to use strategies of information, positive communication, and patient involvement, thus suggesting a communication-centered coping style focused on a recovery pathway (Lauzier-Jobin & Houle, Citation2021). Conversely, the younger the caregiver, the less likely they are to use these strategies, thus suggesting that caregivers should be supported from the first psychotic episode onwards to help implement coping strategies that are beneficial for recovery.

Coping profiles

When comparing coping strategies and styles according to the relationship of family caregivers with the PWS, our results highlight the differences between parents and sibling caregivers. Our profile analyses confirm that the same family caregiver may use more than one coping style when dealing with stressful situations (Sideridis, Citation2006). Further, the results of our study show that while the parents almost exclusively use a single coping profile (undifferentiated coping used by 96.7% of the parents), the siblings have more differentiated coping profiles. Among the group of siblings, 58.3% had an undifferentiated coping profile, 37.5% had a profile centered primarily on the problem-focused coping style, and only 4.2% displayed a profile centered on the emotion and social support coping styles. In general, family caregivers appear to use the undifferentiated coping profile the most, which indicates that caregivers use problem-focused coping styles as often as emotion-focused coping or social support styles. This undifferentiated coping profile could reflect flexibility on the part of the caregivers, who manage to diversify their coping styles according to the situations they face. In particular, it has been shown that good psychological flexibility could alleviate the feelings of distress experienced by family caregivers of persons presenting a first psychotic episode (Jansen et al., Citation2017). Our results also show that the longer the duration of illness of the relative, the more likely it is for caregivers to present an undifferentiated coping profile, thus suggesting that flexibility in the use of different coping styles tends to increase with the experience of being a caregiver. This would explain why Magliano et al. (Citation1998) observed that the emotion-focused coping style is used more as the caregiver gets older; it may be used more than at the beginning but is used just as much as the other coping styles, as shown in our profile analyses.

Our results further indicate that the problem-centered coping profile is 1) more present among sibling caregivers than among parent caregivers, and 2) among caregivers who have been ill for the shortest time. The preferential use of the problem-focused coping style by sibling caregivers seems particularly appropriate while the latter are likely seeking information about the illness. This quest for information is the main need mentioned by siblings of PWS (Davtian, Citation2003). Problem-focused coping is generally considered suitable for family caregivers of PWS (Grover et al., Citation2015; Rexhaj et al., Citation2016; Scazufca & Kuipers, Citation1999). Our results, therefore, suggest that approximately one-third of siblings spontaneously adopt a suitable coping style.

However, in our study, the coping profile focusing on emotion and social support was used exclusively by sibling caregivers, even though only 5% of them used it. Some studies appear to suggest that it would be poorly suited for caregivers of PWS (Creado et al., Citation2006; Rexhaj et al., Citation2016); therefore, siblings may have less effective coping processes than parents. This coping profile reflects the use of a coping style centered not only on emotion but also on social support. There is no consensus in the literature on the use of the social support coping style. While Kate et al. (Citation2013) suggest that such a coping strategy is significantly associated with caregiver burden, Ben-Zur (Citation2009) suggests that it is adapted to respond to a perceived stressful situation.

Implications of the study

Our results show that most family caregivers present an undifferentiated coping profile, thus demonstrating a certain degree of psychological flexibility. However, siblings, unlike parents, appear to show greater rigidity in the coping profiles they adopt, favoring a coping style that is either problem-oriented or emotionally and socially supportive. Therefore, although these coping profiles may be adapted to deal with their specific experiences, it is likely that this group would particularly benefit from individualized support, which would help them to diversify and adopt the coping strategies most relevant to them. More generally, our results suggest that all family members caring for PWS would require targeted support appropriate to their problems and the stage of recovery of the person being cared for (Coloni-Terrapon et al., Citation2019; Rexhaj et al., Citation2017). The Ensemble program, which provides individualized support for family caregivers of people suffering from severe mental illness, could be particularly appropriate as it is based on the specific needs of each participant (Rexhaj et al., Citation2017).

Directions for future research

Family caregivers are not always parents; therefore, distinguishing between siblings and parents was a key step that opens the way to including other caregivers, including informal caregivers outside the nuclear family, such as aunts and uncles, friends and neighbors.

Our results suggest that there is a link between the age of the PWS and the coping strategies adopted by the family caregivers. Further studies of younger PWS and their caregivers would allow us to examine the evolution of coping strategies over the course of the disease (Dillinger & Kersun, Citation2020). Such research would allow for the development of an appropriate system to care for both the PWS and their caregivers from the first signs of the disease.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that need to be highlighted. First, the ratio of men to women was not well balanced. Evidence suggests that the overrepresentation of women is a recurrent feature of samples comprising family caregivers of people with mental disorders (Kamil & Velligan, Citation2019; Onwumere et al., Citation2017) and ours is no exception. Second, the recruitment procedure used may have introduced a sampling bias. As discussed previously, the majority of caregivers in our sample were recruited through associations of relatives of people with mental disorders. Third, the chronicity of schizophrenia can lead to episodic crises in the sufferer, which may require family caregivers to adapt and sometimes modify the type of coping strategies that they use. Therefore, our results are only representative of the time at which the relatives participated in the study. Fourth, the time spent by each participant with their relative suffering from schizophrenia was not known in this study. However, the participants all considered themselves caregivers, which suggests a strong commitment to their relatives.

Conclusion

This study is the first to identify the differences in coping styles of adult caregivers of PWS according to their relationship. Our results show differences in coping strategies and styles, as well as in coping profiles. The profile approach has made it possible, for the first time, to consider coping in a way other than the usual independent approach. The results show three coping profiles, namely, (1) problem-focused, (2) undifferentiated, and (3) emotion-focused and social support. These are used to a greater or lesser extent depending on the relationship of the caregiver to the PWS. These findings suggest that it is important to differentiate between the relational status of caregivers and their individual needs to better understand their investments in their caregiving role and to provide them with adapted support.

Author contributions

LP and SR conceived the study and LP, PG and SR designed it. LP and SR recruited the participants and collected the data. LP, SR, HW and PG analyzed and interpreted the data. LP, HW, and SR wrote the paper. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Ethical approval

Protocol 280/2011, by the Ethics Committee for human-based research in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling : Three-step approaches using M plus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Ben-Zur, H. (2009). Coping styles and affect. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(2), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015731

- Chadda, R. K. (2014). Caring for the family caregivers of persons with mental illness. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(3), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.140616

- Coloni-Terrapon, C., Favrod, J., Clément-Perritaz, A., Gothuey, I., & Rexhaj, S. (2019). Optimism and the psychological recovery process among informal caregivers of inpatients suffering from depressive disorder : A descriptive exploratory study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00972

- Creado, D. A., Parkar, S. R., & Kamath, R. M. (2006). A comparison of the level of functioning in chronic schizophrenia with coping and burden in caregivers. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.31615

- Davtian, H. (2003). Les frères et soeurs de malades psychiques, résultats de l’enquête et réflexions. Unafam.

- Davtian, H. (2010). Le handicap psychique et son retentissement sur la fratrie. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, 168(10), 773–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2010.09.010

- Dillinger, R. L., & Kersun, J. M. (2020). Caring for caregivers: Understanding and meeting their needs in coping with first episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(5), 528–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12870

- Dodge, C. E., & Smith, A. P. (2019). Caregiving as role transition : Siblings’ experiences and expectations when caring for a brother or sister with schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 38(2), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2019-005

- Doron, J., Trouillet, R., Maneveau, A., Ninot, G., & Neveu, D. (2015). Coping profiles, perceived stress and health-related behaviors: A cluster analysis approach. Health Promotion International, 30(1), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau090

- Eisenbarth, C. (2012). Coping profiles and psychological distress: A cluster analysis. North American Journal of Psychology, 14(3), 485–496.

- Grandón, P., Jenaro, C., & Lemos, S. (2008). Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry Research, 158(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.013

- Grover, S., Chakrabarti, & S., Pradyumna. (2015). Coping among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 24(1), 5–11., https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.160907

- Guan, Z., Wang, Y., Lam, L., Cross, W., Wiley, J. A., Huang, C., Bai, X., Sun, M., & Tang, S. (2021). Severity of illness and distress in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: Do internalized stigma and caregiving burden mediate the relationship? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(3), 1258–1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14648

- Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., Brennan, P. L., & Schutte, K. K. (2005). Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658

- Jansen, J. E., Haahr, U. H., Lyse, H.-G., Pedersen, M. B., Trauelsen, A. M., & Simonsen, E. (2017). Psychological flexibility as a buffer against caregiver distress in families with psychosis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01625

- Kamil, S. H., & Velligan, D. I. (2019). Caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia: Who are they and what are their challenges? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(3), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000492

- Kate, N., Grover, S., Kulhara, P., & Nehra, R. (2013). Relationship of caregiver burden with coping strategies, social support, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in the caregivers of schizophrenia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(5), 380–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.014

- Lanza, S. T., Tan, X., & Bray, B. C. (2013). Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling : a Multidisciplinary Journal, 20(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.742377

- Lauzier-Jobin, F., & Houle, J. (2021). Caregiver support in mental health recovery : A critical realist qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 31(13), 2440–2453. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211039828

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Co Inc.

- Magliano, L., Fadden, G., Economou, M., Held, T., Xavier, M., Guarneri, M., Malangone, C., Marasco, C., & Maj, M. (2000). Family burden and coping strategies in schizophrenia: 1-year follow-up data from the BIOMED I study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 35(3), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050192

- Magliano, L., Fadden, G., Madianos, M., Almeida, J. M. C.de, Held, T., Guarneri, M., Marasco, C., Tosini, P., & Maj, M. (1998). Burden on the families of patients with schizophrenia: Results of the BIOMED I study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33(9), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050073

- Magliano, L., Guarneri, M., Marasco, C., Tosini, P., Morosini, P. L., & Maj, M. (1996). A new questionnaire assessing coping strategies in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: Development and factor analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 94(4), 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09853.x

- McFarlane, W. R. (2016). Family interventions for schizophrenia and the psychoses: A review. Family Process, 55(3), 460–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12235

- Meng, N., Chen, J., Cao, B., Wang, F., Xie, X., & Li, X. (2021). Focusing on quality of life in the family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia from the perspective of family functioning. Medicine, 100(5), e24270. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024270

- Ong, H. C., Ibrahim, N., & Wahab, S. (2016). Psychological distress, perceived stigma, and coping among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 9, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S112129

- Onwumere, J., Lotey, G., Schulz, J., James, G., Afsharzadegan, R., Harvey, R., Chu Man, L., Kuipers, E., & Raune, D. (2017). Burnout in early course psychosis caregivers: The role of illness beliefs and coping styles. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 11(3), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12227

- Plessis, L., Golay, P., Wilquin, H., Favrod, J., & Rexhaj, S. (2018). Internal validity of the French version of the Family Coping Questionnaire (FCQ): A confirmatory factor analysis. Psychiatry Research, 269, 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.021

- Plessis, L., Wilquin, H., Pavani, J.-B., & Bouteyre, E. (2020). Explaining differences between sibling relationships in schizophrenia and nonclinical sibling relationships. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00321

- Porcelli, S., Kasper, S., Zohar, J., Souery, D., Montgomery, S., Ferentinos, P., Rujescu, D., Mendlewicz, J., Merlo Pich, E., Pollentier, S., Penninx, B. W. J. H., & Serretti, A. (2020). Social dysfunction in mood disorders and schizophrenia: Clinical modulators in four independent samples. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 99, 109835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109835

- Rexhaj, S., Jose, A. E., Golay, P., & Favrod, J. (2016). Perceptions of schizophrenia and coping styles in caregivers: Comparison between India and Switzerland. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(9-10), 585–594.

- Rexhaj, S., Leclerc, C., Bonsack, C., Golay, P., & Favrod, J. (2017). Feasibility and accessibility of a tailored intervention for informal caregivers of people with severe psychiatric disorders : A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8(178). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00178

- Rexhaj, S., Python, N. V., Morin, D., Bonsack, C., & Favrod, J. (2013). Correlational study: Illness representations and coping styles in caregivers for individuals with schizophrenia. Annals of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-12-27

- Scazufca, M., & Kuipers, E. (1999). Coping strategies in relatives of people with schizophrenia before and after psychiatric admission. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 174(2), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.174.2.154

- Schmid, R., Schielein, T., Binder, H., Hajak, G., & Spiessl, H. (2009). The forgotten caregivers: Siblings of schizophrenic patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 13(4), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651500903141400

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136

- Sideridis, G. D. (2006). Coping is not an ‘either’ ‘or’: The interaction of coping strategies in regulating affect, arousal and performance. Stress and Health, 22(5), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1114

- Sin, J., Murrells, T., Spain, D., Norman, I., & Henderson, C. (2016). Wellbeing, mental health knowledge and caregiving experiences of siblings of people with psychosis, compared to their peers and parents: An exploratory study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(9), 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1222-7

- Smith, M. J., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick Seltzer, M. (2007). Siblings of adults with schizophrenia: Expectations about future caregiving roles. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.29

- Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual: The concise manual for the Professional Quality of Life Scale., 2nd Edition, ProQOL.org.

- Stanley, S., & Balakrishnan, S. (2021a). Informal caregiving in schizophrenia: Correlates and predictors of perceived rewards. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(3), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2021.1904089

- Stanley, S., & Balakrishnan, S. (2021b). Informal caregivers of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia: Determinants and predictors of resilience. Journal of Mental Health, 19(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1952945

- Stein, C. H., Gonzales, S. M., Walker, K., Benoit, M. F., & Russin, S. E. (2020). Self and sibling care attitudes, personal loss, and stress-related growth among siblings of adults with mental illness. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(6), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000511

- van der Meer, L., & Wunderink, C. (2019). Contemporary approaches in mental health rehabilitation. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000343

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

- Young, L., Murata, L., McPherson, C., Jacob, J. D., & Vandyk, A. D. (2019). Exploring the Experiences of Parent Caregivers of Adult Children With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.08.005

- Yu, W., Chen, J., Hu, J., & Hu, J. (2019). Relationship between mental health and burden among primary caregivers of outpatients with schizophrenia. Family Process, 58(2), 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12340

- Yusuf, A. J., & Nuhu, F. T. (2011). Factors associated with emotional distress among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Katsina, Nigeria. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0166-6