Abstract

Background

Black people in the United Kingdom disproportionately acquire long-term health conditions and are marginalised from the labour market compared with other groups. These conditions interact and reinforce high rates of unemployment among Black people with long-term health conditions.

Aims

To examine the efficacy, and experience, of employment support interventions in meeting the needs of Black service users in Britain.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted focusing on peer-reviewed literature featuring samples drawn from the United Kingdom.

Results

The literature search revealed a paucity of articles that include analysis of Black people’s outcomes or experiences. Six articles met the selection criteria of the review, of which five focused on mental health impairments. No firm conclusions could be drawn from the systematic review; however, the evidence suggests that Black people are less likely than their White counterparts to secure competitive employment and that Individual Placement and Support (IPS) may be less effective for Black participants.

Conclusions

We argue for a greater focus on ethnic differences in employment support outcomes with an emphasis on how such services may remediate racial differences in employment outcomes. We conclude by foregrounding how structural racism may explain the dearth of empirical evidence in this review.

Keywords:

Black people in the UK are less likely than their White counterparts to be in employment, and those Black people who are employed, are more likely to occupy low-paid, precarious work (Trades Union Congress, Citation2020; Li & Heath, Citation2020). Such jobs can have a detrimental effect on a person’s physical and mental health (Llosa et al., Citation2018; Marmot et al., Citation2001). As several audit studies have shown, Black people, suffer an ethnic penalty in the labour market, receiving lower call-back rates based on their names alone even where they have similar qualifications to their White counterparts (Berthoud, Citation2000; Heath & Di Stasio, Citation2019). Racism is a likely factor explaining these differential outcomes in employment rates between Black people and the rest of the population (Tew et al., Citation2012).

Another group who are less likely to be in employment are people with long-term health conditions (Antao et al., Citation2013; Kirsh et al., Citation2009). Unemployment in turn, negatively influences health, contributing to the development of additional comorbidities (Wanberg, Citation2012), which reduces the likelihood of sustaining meaningful employment (Marwaha et al., Citation2007). However, long-term health conditions are unequally distributed across society, and some groups are disproportionately affected. People racialised as Black are one such group.

Black people are more likely to be diagnosed with long-term health conditions such as hypertension, heart disease and stroke and additionally acquire comorbidities more rapidly than their White counterparts (Brown et al., Citation2012; Guy’s & St Thomas’ Charity, Citation2018). The excessive burden of poor health extends to mental health problems, where Black people disproportionately require mental health services (Arai & Harding, Citation2004; Boydell et al., Citation2013), are more likely to be in-patients and more likely to experience compulsory hospital admission (Bhui et al., Citation2003). The presence of these mental health conditions is associated with poorer labour market outcomes (Harvey et al., Citation2009).

Taken together, the evidence suggests that Black people with pre-existing long-term health conditions are particularly marginalised from the labour market. As such, this group are in need of employment support programmes, which have been shown to protect against long-term ill health and increase the likelihood of recovery (Bartley et al., Citation2004). However, given the potential double disadvantage in employment faced by Black people, relating to both their race and health, it is important to understand how these multiple burdens and their interaction may complicate the efficacy of employment support services. It is unclear whether employment support interventions designed to support people with long-term health conditions can overcome the additional effects of anti-Black racism.

To explore this issue, we conducted a systematic narrative review focusing on studies that report on employment support interventions featuring Black participants. Crucially, the review focuses on articles where the specific effects on Black participants are discussed.

Employment support for people with long-term health conditions

Employment support interventions for people with long-term health conditions have received increasing policy focus in the United Kingdom (Corbiere & Lecomte, Citation2009; Crowther et al., Citation2001; Jenaro et al., Citation2002; Schneider, Citation1998). These interventions are bifurcated by their relative focus on training and job placement, and the order in which they do them (Modini et al., Citation2016). Broadly speaking, employment support interventions either emphasise ‘train then place’ or ‘place then train’ models.

The various train-place models may combine one or more elements of sheltered or transitional employment and pre-vocational training. These approaches aim to prepare people for employment through training, improving work readiness and helping them develop resumes and interview skills. Partcipants in such programmes may also gain work in a sheltered, non-competitive environment, sometimes through a ‘Clubhouse’ model (McKay et al., Citation2018). At a later stage, there may be the possibility of moving into competitive employment.

Place-train models have gained more prominence in recent years. The best-known is Individual Placement and Support (IPS), and variants of this model. The aim of the model is to place people who want to work into competitive employment and then train them on the job. This approach involves the provider working in partnership with clinical teams and employers to find jobs based on clients’ preferences. In particular, it focuses on rapid job searching (Bond et al., Citation2011). There is a wealth of evidence suggesting that IPS creates positive employment outcomes for participants (Kinoshita et al., Citation2013; Knapp et al., Citation2013; Luciano et al., Citation2014; Modini et al., Citation2016). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis shows that recipients of IPS are more than twice as likely as non-recipients to find competitive employment (Brinchmann et al., Citation2020).

Alternative models that are less well evidenced in the literature include transitioning people into self-employment (Rizzo, Citation2002). These might show promise for people who are furthest away from the employment market and have been piloted with people with severe mental illness and criminal history (Samele et al., Citation2018).

Aim of this review

The present systematic literature review seeks to understand the effects of employment support in the context of the United Kingdom. Building on the extant literature, we seek to understand the effectiveness, and experience of, employment support in the UK for Black people with long-term mental or physical health conditions.

Method

Search strategy

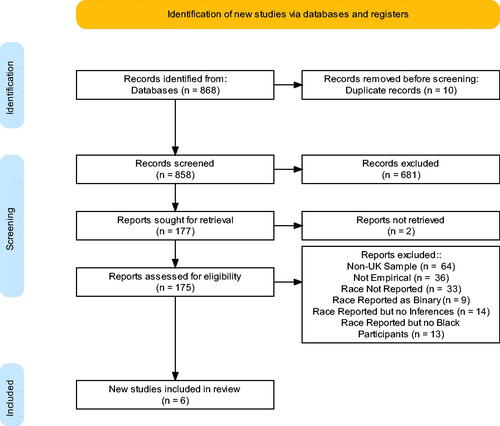

The systematic literature review follows a structured methodology and is reported using the PRISMA guidelines (Siddaway, Wood and Hedges, Citation2019), although it was not registered. Using search strings related to race, health, location and employment support, we searched three meta-databases; Web of Science Core Collection, EBSCOhost and OVID (Embase, PsycArticles, PsycInfo), to obtain relevant publications for the review. Specifically, we searched these databases for unemployment (unemploy*) and ethnicity (black* or ethnic* or race) and terms related to employment support (“individual placement and support” or “supported employment” or “employment support” or “assisted employment” or “vocational rehabilitation”), location (“United Kingdom” or “UK” or “Britain” or “Scotland” or “Wales” or “Northern Ireland” or “England”) and finally health condition (“mental health” or “physical health” or “mental illness”). These terms could appear anywhere in the text. Our searches were limited to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English. Search results were not limited by publication date however, we are restricted to peer-reviewed literature published before 5 April 2020 when the searches were conducted.

Eligibility criteria and selection

Studies were included in the review if they met four criteria. First, given that race and racism are understood differently, and may have different effects, across cultural contexts we limited the review to empirical studies where the participants were located in the United Kingdom. Second, the study must have included participants who are identified as Black (or another category with the same substantive meaning e.g. Afro-Caribbean, African). In addition, any analysis of either quantitative or qualitative nature must make inferences about this group, as distinct from a broader non-White grouping. Third, the study must have a substantive focus on the long-term ill health of a physical and/or psychological nature. Finally, the study must focus on employment support broadly defined. That is, the study either reports on an intervention directly, or the experiences of citizens who have had/are having an intervention.

Results

The searches resulted in 868 potentially relevant publications. These articles were reviewed using a step-by-step process. First, publications were screened for relevance by title and abstract after removing duplicates (N = 10). This resulted in 175 publications that were included for full-text analysis (two could not be retrieved owing to retraction). These remaining manuscripts were assessed independently by two authors (CO, YI) and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. A total of 169 articles were excluded following full-text review because they used a non-UK Sample (N = 64), were not empirical (i.e. were conceptual/theoretical and included no primary or secondary data, N = 36), did not report race or ethnicity (N = 33), reported race in a binary format such that Black participants were not distinguishable from other groups (N = 9), did not make inferences about Black participants based on the analysis (N = 14), or had no Black participants (N = 13).

Six manuscripts were agreed upon for inclusion in the review and given the small number of articles a narrative approach is most appropriate for reporting our findings (see ). describes the articles included in the systematic review, reporting their methodological approach, total sample, total Black sample, and the nature of the study.

Table 1. Studies, year of publication and sample characteristics.

It seems clear that despite the obvious discrimination faced by Black people with long-term health conditions, the published literature provides little direction either about the overall experiences of Black people receiving employment support, or the effectiveness of such support. In fact, according to at least one paper ‘evidence-based’ models such as Individual Placement and Support (IPS) appear to be ineffective when a large proportion of participants are Black (Howard et al., Citation2010).

Perceptions of Black people with long-term health conditions

Secker et al. (Citation2001) use a mixed qualitative approach to understand the perceived barriers to employment and potential solutions for mental health service users. Specifically, participants were recruited who were on ‘Care Programme Approach (CPA)’ levels two and three, i.e., those with the greatest support needs. Study two of the paper examines focus groups conducted with mental health service users, including two from African and Caribbean Mental Health Services.

In general, participants highlighted the fear of losing benefits and a lack of impartial advice as a significant barriers to accessing employment, education or training (Secker et al., Citation2001). Additionally, Black participants stressed how both institutional and personal racism exacerbated the stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness. Participants across focus groups proposed a range of solutions. These included impartial benefits advice, expert careers advice, peer support and the strengthening of anti-discrimination legislation. Nevertheless, specific needs were highlighted by Black participants which differed from other participants. Black participants particularly valued open competitive employment at market rates above sheltered employment.

These findings are buttressed in the ethnographic work of Qureshi et al. (Citation2014), which explores the relationship between long-term ill health, poverty and ethnicity in East London. The comparative qualitative analysis focuses on four ethnic groups – Ghanaian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and White British. The analysis accounts for historical migration patterns whereby highly educated Ghanaians (and others) were purposely recruited for skilled workers in the public sector. Nevertheless, Black participants in this study experienced long-term sickness in different ways to other groups. In particular, the study notes how accessing legal entitlements to employment support such as adaptations, sick pay and sick leave are contingent on supportive, informal relationships with managers. The strength of such relationships may be informed not only by the nature and length of sickness but also other social identity dynamics such as race, ethnicity and culture.

Longitudinal vocational trajectories of Black people with long-term sickness

Using longitudinal data, Hodgekins et al. (Citation2015) tracked the social recovery trajectories of 764 individuals with first-episode psychosis through early intervention services over 12 months. Social recovery was assessed using a Time Use Survey, which measured time spent in structured activity (including paid and voluntary work, education, housework and childcare, leisure, and sports). Latent class growth analysis applied to the data identified three latent classes of social recovery. These were Low-Stable, where social disability was high and remained high over 12 months, Moderate-Increasing, where social disability was moderate but improved over time, and High-Decreasing, where social disability was low but tended to increase over the analysis period. Black people in the study were significantly more likely to be in the Low-Stable class suggesting high levels of social disability and little improvement over 12 months. Thus, being racialised as Black was associated with less structured activity compared with White counterparts.

Other longitudinal evidence is somewhat contradictory. In Tapfumaneyi et al. (Citation2015), 1013 first-episode psychosis patients were tracked over one year through early intervention services to understand predictors of vocational activity. The study shows that Black African participants were more likely to be in education at one-year follow-up compared with their White counterparts. However, there were no differences in the likelihood of gaining employment among ethnic groups. Higher participation in education among Black Africans is explained through an appeal to Black African cultural norms which are supposed to place greater emphasis on educational attainment. Nevertheless, following this evidence we may expect greater educational attainment among Black Africans to manifest in more positive outcomes in employment, though this was not the case.

Individual placement and support

In a longitudinal study of the effectiveness of Individual placement and support (IPS), Rinaldi & Perkins (Citation2007) show markedly increased competitive employment among participants who engaged with IPS services. The study compares IPS services with typical vocational support offered by care coordinators across two London boroughs. Results showed that 46% of participants using IPS improved their vocational status after six months compared to 30% of those not receiving the service. After 12 months, 62% had improved their vocational status in IPS compared with 37% of those supported by a care coordinator. These differences were statistically significant.

Concerning race specifically, a comparison between ethnic groups showed no significant differences in the proportion of people in open employment after six or 12 months. Although it is noted that Asian people in the sample were more likely to be in open employment at baseline. Thus, in this study, IPS seems to create similar outcomes for Black clients compared with other racial groups. However, the authors recognize that the “design used does not allow confident statements about causality” (Rinaldi & Perkins, Citation2007, p. 245).

Randomised control trials are often considered a ‘gold standard’ and can be useful in determining the causal effect of an intervention (Cartwright, Citation2010). In this vein, Howard et al. (Citation2010) tested the effectiveness of IPS compared with treatment as usual (i.e. ‘train-place’ approaches involving psychosocial rehabilitation and preparation for employment). In particular, the study aimed to assess whether at 1-year follow-up a significantly greater percentage of individuals who received IPS would be in open competitive employment compared with those receiving treatment as usual. The IPS element of the RCT was conducted across two sites, and both were rated as having good fidelity to the IPS model. Nevertheless, the study concluded that there was no evidence that IPS was better than treatment as usual in helping people with severe mental illness to gain competitive employment.

The authors note that 62% of the study sample were ethnic minorities (41% Black in the control condition and 45% Black in the treatment condition) and that this may have limited the success of the intervention. Expressly, “the relatively high proportion of participants from ethnic groups other than White (62%) could also limit the success of IPS in the UK, as people from other ethnic groups are more likely to be unemployed in the UK” (Howard et al., Citation2010, p. 409). This suggests that IPS programmes (even if they are effective) may not compensate for racial discrimination in recruitment practices that affect people racialised as Black.

General discussion

It is clear from the available literature that Black people disproportionately bear the burden of long-term health conditions in the UK, whilst simultaneously being marginalised from the labour market. Yet, an array of evidence suggests that employment can assist with recovery and protects health. As such, employment support for Black people with long-term health conditions is particularly important because this group especially faces health and employment inequalities. However, it is also possible that employment support interventions may not be able to overcome the interwoven discrimination related to both health status and race. The current review sought to assess the experience, and effectiveness, of employment support for Black people with long-term health conditions.

The results of our literature search revealed only six articles that met our criteria. Race reporting in the employment support literature lacks detail and 42 articles were rejected either because they did not report race at all or because race was reported as binary (i.e., White and non-White or some variation of this theme). A further 13 articles were rejected because they did not include any Black participants.

Despite the clear rationale for research which focuses on the needs of Black citizens, little research has been conducted that analyses the results of employment support with attention to race. The lack of research that deals explicitly with the influence of race is prevalent in other academic disciplines and may represent a broader issue in academia itself. For instance, in a longitudinal study of articles published in ‘top tier’ psychology journals, Roberts et al. (Citation2020) have shown that, over the past 50 years, only 5% of publications highlighted race in the title or abstract. The lack of publications in our review concurs with this data and suggests that little attention has been paid to the dynamics of race with employment support interventions, despite an obvious rationale for doing so.

Overall, this narrative systematic review provides a complicated and somewhat disjointed understanding of the experiences and effects of employment support for Black citizens in the UK. First, as highlighted in the motivation for this review, Black people report that racism exacerbates the stigmatisation associated with disability. Concurrently, Black people reportedly value open employment over and above sheltered employment (Secker et al., Citation2001). However, where studies have assessed employment outcomes, the best evidence suggests that Black people are less likely than their White counterparts to secure such work, but more likely to go into education (Tapfumaneyi et al., Citation2015). This contradiction, between Black people’s stated goal of competitive employment and the empirical findings related to education, is not resolved within the literature. Moreover, other large-scale studies suggest that Black citizens are less likely overall to recover from social disability following the first episode of psychosis, i.e., they were more likely to spend less time in structured activity, and for the amount of time spent in structured activity to remain low over 12-months (Hodgekins et al., Citation2015). Put another way, standard practice related to the first episode of psychosis seems to be ineffective in reducing social disability for Black service users.

Concerning IPS, which is seen to be both the best evidenced and most promising employment support intervention for people with long-term mental health conditions – evidence from an RCT suggests that where Black people make up a large proportion of the participants, the intervention may be ineffective (Howard et al., Citation2010). This finding may suggest that IPS is not able to overcome the dual effects of both ableism and racism faced by Black participants with long-term mental health conditions in the labour market. Nevertheless, observational studies have shown that there are no statistically significant differences between ethnic groups in IPS programmes (Rinaldi & Perkins, Citation2007). Indeed, new cross-sectional evidence continues to support the claim that outcomes across ethnic groups within IPS programmes are substantively the same – such that Black participants have a similar likelihood of employment as other groups (Perkins et al., Citation2022).

Our review does not enable us to conclude with conviction that any form of intervention is effective for Black people with long-term health conditions. The available evidence does however confirm that following first-episode psychosis Black people have poorer employment outcomes than other groups (Hodgekins et al., Citation2015; Tapfumaneyi et al., Citation2015). The literature also suggests that Black people report a desire for paid competitive employment and additional barriers to employment in comparison with other groups. Namely that racism exacerbated the stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness, marginalising them from the labour market (Secker et al., Citation2001). Given the known relationship between vocational activity and recovery, it is likely that Black people’s marginalisation from the labour market contributes to their overrepresentation in coercive mental health services and entry through ‘crisis routes’ (Bhui et al., Citation2003). That is to say, the discrimination faced by Black people in the labour market coupled with a long-term health condition may contribute to the exacerbation of an existing health condition, particularly poor mental health (Wickham et al., Citation2020).

Evidence from the United States shows that the underlying mechanisms of race-related health disparities differ across groups. The Black population is characterised by cumulative disadvantage which increases the level of serious illness faced by Black Americans during their 50’s and 60’s (Brown et al., Citation2012). Structural inequality faced by Black people in the UK may similarly be explained through the lens of cumulative disadvantage, which suggests that racial health disparities increase over the life course. From this perspective, early intervention becomes crucial to slowing the progression of health inequalities.

Limitations

This narrative review, and the literature it drew from, have two important limitations. First, there are a low number of studies included in this review. The inclusion of samples from other geographies may have increased the number of studies available and made meta-analyses possible. However, social representations of race, disability and effective modes of intervention are culturally bounded and do not translate perfectly across cultures. As such, the experiences of Black Britons in employment support, and more broadly, are not wholly the same as the experiences of other African diasporas. For these reasons, the study specifically focused on the UK context rather than applying a broader range of inclusion criteria. Although this limits the range of literature that we can examine, it also highlights the need for new research in the UK.

Another reason for the low number of included articles may be the other search parameters. Different search terms may have generated broader literature, especially via the inclusion of ‘grey’ literature such as these and service reviews (Robotham & Couperthwaite, Citation2020; Wrynne, Citation2017). In relation to the search terms in particular, a different set of phrases may have altered the outcome of the review. However, given that we allowed our search terms to appear anywhere in the article text, we have confidence that this is sufficiently inclusive and provided a high chance of accessing the majority of relevant literature.

Secondly, a disproportionate number of the studies included in the review are specifically focused on mental health. Although we aimed to understand employment support for Black people with long-term health conditions in a broad sense, only one of the six included articles features participants who are not mental health service users. Thus, the review provides little indication of the effectiveness of employment support for Black individuals with physical health conditions. This may be reflective of the wider welfare policy environment in the UK which is characterised by increasing conditionality, particularly targeting those who are unemployed and Disabled, as well as those with mental health impairments (Dwyer et al., Citation2020).

Future research

We recommend that researchers studying employment support consider demographic factors in their studies including, but not limited to, race/ethnicity. It is clear that demographic differences are implicated in the likelihood of gaining employment and that multiple individual attributes interact to shape social outcomes (Crenshaw, Citation1989). More specifically, the fact that one is both Black and has a long-term health condition at least has the potential to influence the effectiveness of employment support interventions. Researchers should be mindful to explore potential differences between groups by ensuring the collection of high-quality demographic data which goes beyond analysing simple “White/non-White” binaries.

Conclusion

The lack of empirical evidence relating to the experiences and outcomes of Black people in employment support is characterised by structural racism. Structural racism is the formalisation of “macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial and ethnic groups” (Gee & Ford, Citation2011, p. 3; Powell, Citation2008). Multiple lines of evidence support this conclusion. Namely that previous research highlighted in this paper identifies Black people as being more likely to be marginalised from the labour market and more likely to have a long-term health conditions. In parallel, it has been shown that research which deals with race explicitly is marginalised from the academic discourse. In this way, poor outcomes for members of Black communities are held in place by a lack of attention to their social conditions. Although recent events around the world have brought renewed focus on racial disparities, there are many areas where the experiences of Black people are persistently ignored. In this article, we have highlighted one such area where research is sorely lacking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antao, L., Shaw, L., Ollson, K., Reen, K., To, F., Bossers, A., & Cooper, L. (2013). Chronic pain in episodic illness and its influence on work occupations: A scoping review. Work, 44(1), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-01559

- Arai, L., & Harding, S. (2004). A review of the epidemiological literature on the health of UK-born Black Caribbeans. Critical Public Health, 14(2), 81–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/109581590410001725355

- Bartley, M., Sacker, A., & Clarke, P. (2004). Employment status, employment conditions, and limiting illness: Prospective evidence from the British household panel survey 1991–2001. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 58(6), 501–506. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.009878

- Berthoud, R. (2000). Ethnic employment penalties in Britain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 26(3), 389–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/713680490

- Bhui, K., Stansfeld, S., Hull, S., Priebe, S., Mole, F., & Feder, G. (2003). Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK: Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.2.105

- Bond, G. R., Becker, D. R., & Drake, R. E. (2011). Measurement of fidelity of implementation of evidence-based practices: case example of the IPS fidelity scale. Clinical Psychology, 18(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01244.x

- Boydell, J., Bebbington, P., Bhavsar, V., Kravariti, E., van Os, J., Murray, R. M., & Dutta, R. (2013). Unemployment, ethnicity and psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 127(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01921.x

- Brinchmann, B., Widding-Havneraas, T., Modini, M., Rinaldi, M., Moe, C. F., McDaid, D., Park, A. L., Killackey, E., Harvey, S. B., & Mykletun, A. (2020). A meta-regression of the impact of policy on the efficacy of individual placement and support. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(3), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13129

- Brown, T. H., O'Rand, A. M., & Adkins, D. E. (2012). Race-ethnicity and health trajectories: Tests of three hypotheses across multiple groups and health outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146512455333

- Cartwright, N. (2010). What are randomised controlled trials good for? Philosophical Studies, 147(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9450-2

- Corbiere, M., & Lecomte, T. (2009). Vocational services offered to people with severe mental illness. Journal of Mental Health, 18(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701677779

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). HeinOnline – 1989. . The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–168.

- Crowther, R. E., Marshall, M., Bond, G. R., & Huxley, P. (2001). Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: Systematic review. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 322(7280), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7280.204

- Dwyer, P., Scullion, L., Jones, K., McNeill, J., & Stewart, A. B. R. (2020). Work, welfare, and wellbeing: The impacts of welfare conditionality on people with mental health impairments in the UK. Social Policy & Administration, 54(2), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12560

- Gee, G. C., & Ford, C. L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old Issues. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000130

- Guy’s & St Thomas’ Charity. (2018). From one to many: Exploring people’s progression to multiple long-term conditions in an urban environment.

- Harvey, S. B., Henderson, M., Lelliott, P., & Hotopf, M. (2009). Mental health and employment: Much work still to be done. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(3), 201–203. (Issue https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055111

- Heath, A. F., & Di Stasio, V. (2019). Racial discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: a meta-analysis of field experiments on racial discrimination in the British labour market. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 1774–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12676

- Hodgekins, J., Birchwood, M., Christopher, R., Marshall, M., Coker, S., Everard, L., Lester, H., Jones, P., Amos, T., Singh, S., Sharma, V., Freemantle, N., & Fowler, D. (2015). Investigating trajectories of social recovery in individuals with first-episode psychosis: A latent class growth analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(6), 536–543. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153486

- Howard, L. M., Heslin, M., Leese, M., McCrone, P., Rice, C., Jarrett, M., Spokes, T., Huxley, P., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Supported employment: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(5), 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061465

- Jenaro, C., Mank, D., Bottomley, J., Doose, S., & Tuckerman, P. (2002). Supported employment in the international context: An analysis of processes and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 17(1), 5–21.

- Kinoshita, Y., Furukawa, T. A., Kinoshita, K., Honyashiki, M., Omori, I. M., Marshall, M., Bond, G. R., Huxley, P., Amano, N., & Kingdon, D. (2013). Supported employment for adults with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(9), 1-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008297.pub2

- Kirsh, B., Stergiou-Kita, M., Gewurtz, R., Dawson, D., Krupa, T., Lysaght, R., & Shaw, L. (2009). From margins to mainstream: What do we know about work integration for persons with brain injury, mental illness and intellectual disability? Work, 32(4), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0851

- Knapp, M., Patel, A., Curran, C., Latimer, E., Catty, J., Becker, T., Drake, R. E., Fioritti, A., Kilian, R., Lauber, C., RöSSLER, W., Tomov, T., Van Busschbach, J., Comas-Herrera, A., White, S., Wiersma, D., & Burns, T. (2013). Supported employment: Cost-effectiveness across six European sites. World Psychiatry, 12(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20017

- Li, Y., & Heath, A. (2020). Persisting disadvantages: a study of labour market dynamics of ethnic unemployment and earnings in the UK (2009–2015). Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(5), 857–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539241

- Llosa, J. A., Menéndez-Espina, S., Agulló-Tomás, E., & Rodríguez-Suárez, J. (2018). Incertidumbre laboral y salud mental: Una revisión meta-analítica de las consecuencias del trabajo precario en trastornos mentales. Anales de Psicología, 34(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.2.281651

- Luciano, A., Drake, R. E., Bond, G. R., Becker, D. R., Carpenter-Song, E., Lord, S., Swarbrick, P., & Swanson, S. J. (2014). Evidence-based supported employment for people with severe mental illness: Past, current, and future research. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 40(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-130666

- Marmot, M., Ferrie, J., Newman, K., & Stansfeld, S. (2001). The contribution of job insecurity to socio-economic inequalities. Economic and Social Reseach Council, May, 0–4.

- Marwaha, S., Johnson, S., Bebbington, P., Stafford, M., Angermeyer, M. C., Brugha, T., Azorin, J. M., Kilian, R., Hansen, K., & Toumi, M. (2007). Rates and correlates of employment in people with schizophrenia in the UK, France and Germany. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020982

- McKay, C., Nugent, K. L., Johnsen, M., Eaton, W. W., & Lidz, C. W. (2018). A Systematic Review of Evidence for the Clubhouse Model of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0760-3

- Modini, M., Tan, L., Brinchmann, B., Wang, M. J., Killackey, E., Glozier, N., Mykletun, A., & Harvey, S. B. (2016). Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.165092

- Perkins, R., Patel, R., Willett, A., Chisholm, L., & Rinaldi, M. (2022). Individual placement and support: cross-sectional study of equality of access and outcome for Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. BJPsych Bulletin, 46(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.9

- Powell, J. A. (2008). Structural racism: Building upon the insights of John Calmore. North Carolina Law Review, 86(3), 791–816. http://www.gnocdc.org/orleans/8/22/people.htm.

- Qureshi, K., Salway, S., Chowbey, P., & Platt, L. (2014). Long-term ill health and the social embeddedness of work: a study in a post-industrial, multi-ethnic locality in the UK. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(7), 955–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12128

- Rinaldi, M., & Perkins, R. (2007). Implementing evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31(7), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.106.010199

- Rizzo, D. C. (2002). With a little help from my friends: Supported self-employment for people with severe disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 17(2), 97–105.

- Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709

- Robotham, D., & Couperthwaite, L. (2020). Work Well, An Evaluation. https://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Work-Well-Final-Report-August-2020.pdf

- Samele, C., Forrester, A., & Bertram, M. (2018). An evaluation of an employment pilot to support forensic mental health service users into work and vocational activities. Journal of Mental Health, 27(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1276527

- Schneider, J. (1998). Models of specialist employment for people with mental health problems. Health and Social Care in the Community, 6(2), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2524.1998.00110.x

- Secker, J., Grove, B., & Seebohm, P. (2001). Challenging barriers to employment, training and education for mental health service users: The service user’s perspective. Journal of Mental Health, 10(4), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230120041155

- Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- Tapfumaneyi, A., Johnson, S., Joyce, J., Major, B., Lawrence, J., Mann, F., Chisholm, B., Rahaman, N., Wooley, J., & Fisher, H. L. (2015). Predictors of vocational activity over the first year in inner-city early intervention in psychosis services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 9(6), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12125

- Tew, J., Ramon, S., Slade, M., Bird, V., Melton, J., & Le Boutillier, C. (2012). Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of the evidence. British Journal of Social Work, 42(3), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr076

- Trades Union Congress. (2020). Dying on the Job

- Wanberg, C. R. (2012). The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 369–396. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100500

- Wickham, S., Bentley, L., Rose, T., Whitehead, M., Taylor-Robinson, D., & Barr, B. (2020). Effects on mental health of a UK welfare reform, universal credit: A longitudinal controlled study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(3), e157–e164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30026-8

- Wrynne, C. (2017). Individual Career Management [Kings College London]. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/88100276/2018_Wrynne_Claire_1018108_ethesis.pdf