Abstract

Background

Many anti-stigma programs for healthcare workers already exist however there is less research on the effectiveness of training in skills for health professionals to counter stigma and its impacts on patients.

Aims

The objective of this study was to examine the theory base, content, delivery, and outcomes of interventions for healthcare professionals which aim to equip them with knowledge and skills to aid patients to mitigate stigma and discrimination and their health impacts.

Methods

Five electronic databases and grey literature were searched. Data were screened by two independent reviewers, conflicts were discussed. Quality appraisal was realized using the ICROMS tool. A narrative synthesis was carried out.

Results

The final number of studies was 41. In terms of theory base, there are three strands - responsibility as part of the professional role, correction of wrongful practices, and collaboration with local communities. Content focusses either on specific groups experiencing health-related stigma or health advocacy in general.

Conclusions

Findings suggest programs should link definitions of stigma to the role of the professional. They should be developed following a situational analysis and include people with lived experience. Training should use interactive delivery methods. Evaluation should include follow-up times that allow examination of behavioural change. PROSPERO, ID: CRD42020212527

Introduction

In 1998, The Lancet published an essay by Norman Sartorius, entitled “Stigma: what can psychiatrists do about it?” (Sartorius, Citation1998). Focusing particularly on schizophrenia, he recommended that psychiatrists expand the focus of clinical work beyond symptom reduction to improving quality of life; reflect on and try to improve their own attitudes, by updating their clinical knowledge and learning from patients and their families about the impact of the illness and of stigma on them; monitor for discrimination and expand their role include to advocacy; and learn from others about how stigma and discrimination can be reduced.

More than twenty years later, it is worth considering the progress against these recommendations. Outcomes other than clinical ones are widely used in research and routine practice, and the concept of personal recovery has had a significant impact on mental health policy and practice in many countries (Le Boutillier et al., Citation2011). Further, continuing professional development is embedded in the requirements for license renewals and revalidation for many professionals. Reflective practice is used extensively in undergraduate and postgraduate training which in theory provides scope for examining one’s own attitudes to people with a mental disorder (Schutz, Citation2007). Stigma among health professionals, including mental health professionals, is an increasing focus of research (Henderson et al., Citation2014).

However, many people with mental disorders report contact with healthcare professionals as the most stigmatizing (Bates & Stickley, Citation2013). Health professionals’ stigma may lead to overlooking and underestimating the physical health of patients with mental health disorders (Liu et al., Citation2017). For example, people with mental health disorders receive a lower quality of care for physical health issues such as cardiovascular disease (Kugathasan et al., Citation2018) and diabetes (Mitchell et al., Citation2009), which may in part be due to lower referral rates of patients with mental health disorders to specialists or prescriptions (Corrigan et al., Citation2014). Moreover, health professionals often engage in stigmatizing practices such as labelling (Perry et al., Citation2020; Schulze, Citation2007), which may lead to not engaging with the patient or examining their problem fully (Carrara et al., Citation2019). These processes have been identified as contributors (Liu et al., 2017) to the reduced life expectancy in high-income countries of 15–20 years for people with severe mental illness, which may be even greater in low- and middle-income countries (Fekadu et al., Citation2015; Wahlbeck et al., Citation2011; Walker et al., Citation2015). It is useful to emphasise the power of health professionals as decision-makers at the individual and organisations levels, following Link and Phelan’s definition of stigma as the co-occurrence of labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in a context in which power is exercised (Link & Phelan, Citation2001).

Consequently, healthcare professionals have been the target of several national campaigns to reduce mental health-related stigma (One of Us in Denmark (Bratbo & Vedelsby, Citation2017), Opening minds in Canada (Stuart et al., Citation2014)). Trainings delivered through such campaigns have mainly focused on reducing provider bias and discrimination, showing short-term changes in knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes (Friedrich et al., Citation2013; Knaak, Citation2018). Reviews of anti-stigma interventions encompassing health professionals show similar findings and emphasise the need for longer term follow-up and the need to use behavioural outcome measures (Henderson et al., Citation2014; Mehta et al., Citation2015; Thornicroft et al., Citation2016). Their effect on providers’ behaviours and consequently patients’ health outcomes in the long term is unknown.

On the other hand, the potential for health professionals’ leadership in reducing the impact of mental health discrimination on their patients has not been examined extensively. Previous articles have acknowledged the potential impact that physicians’ advocacy could have in reducing discrimination (Arboleda-Flórez & Stuart, Citation2012; Thornicroft et al., Citation2010; Ungar et al., Citation2016), agreeing professionals could champion anti-stigma efforts, including much-needed structural changes as health care quality improvement and policy change work. The extent to which stigma reduces mental health professionals’ ability to provide effective care includes relative underfunding for mental health services, barriers to seeking and engaging with treatment, obstacles to rehabilitation due to discrimination in employment and within social networks, reluctance to pursue economic and social opportunities due to the anticipation of discrimination, and negative self-evaluation due to internalised stigma. However, there is little evidence that advocacy and effective stigma reduction methods have been incorporated into the role of psychiatrists or other mental health professionals, (Henderson et al., Citation2014; Mehta et al., Citation2015; Thornicroft et al., Citation2016; Zäske et al., Citation2014). As a result, how anti- stigma advocacy should be incorporated by mental health professionals is not yet clear.

The rationale for this review, therefore, is that we need to return to Sartorius’s recommendation and to learn from those fields of medicine in which there is an increasing focus on physicians’ social accountability and advocacy. Across North America, several organizations have expressed a pressing need for advocacy training in medical education (ACGME, Citation2007; Frank et al., Citation2015; Shaws et al., Citation2017). The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada published a CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework, introducing health advocacy as one of six main competencies which medical education programs should address (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Citation2011). The role of a health advocate is defined as to “identify and understand needs, speak on behalf of others when required, and support the mobilization of resources to effect change” (Frank et al., Citation2015). A series of articles in Canadian Family Physician (Buchman et al., Citation2016; Goel et al., Citation2016; Meili et al., Citation2016; Woollard et al., Citation2016) describes health advocacy activities in pursuit of social accountability at the levels of individual patients or families (micro), at the level of the local community (meso) and at the national or international level (macro). Training based on this spectrum, therefore, includes a variety of skills, whether this be helping a patient consider the pros and cons of self-disclosure of a concealable health condition (micro), working at the interface of health and other sectors to improve local services (meso) or campaigning for policy change (macro). As these may appear disparate, the ability to identify the right level of advocacy to address a particular issue necessitates such a spectrum approach. These skills can be taught at the undergraduate level to reinforce the idea of social accountability as part of professional identity, while postgraduate training can be tailored to specialty.

The aim of the present study is to examine the theory base, content, delivery, and evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of interventions for healthcare professionals or healthcare students which aim to equip them with knowledge and skills to aid their patients to mitigate stigmatization and its health impacts. Such interventions may also aim to improve professionals’ or students’ attitudes to patients with stigmatised health conditions, particular individual characteristics, or from specific communities, but this cannot be the sole aim for inclusion in this review. To operationalise this aim, we address two research questions: “What are the theory base, content, and delivery methods of training for health professionals/students who provide direct patient care to reduce discrimination and its health impact on patients?” and “What is the evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of programs with respect to knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards addressing discrimination and its health impact on patients?” Our future goal is for the results to inform the creation of interventions for mental health professionals, targeted at mental health stigma.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and narrative synthesis. A study protocol was written after initial scoping searches and background reading (available in PROSPERO, ID: CRD42020212527).

Eligibility criteria

There were two sets of inclusion criteria, Table S1 in the supplementary material shows the PICO charts for both research questions. Participants’ inclusion criteria were common to both i.e. all had to be health professionals or healthcare students. Study design inclusion criteria differed: for the first research question any design was included while for the second research question empirical studies that reported feasibility outcomes e.g. recruitment and retention rates, satisfaction, or acceptability outcomes were included. All studies included had to be completed, therefore protocols were excluded. All languages were included, however, the abstract had to be in English.

Table 1. Data extraction.

Information sources and search strategy

Data were collected through five different databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid) to search studies from the medical environment; PsycINFO (via Ovid) to search studies from the mental health stigma perspective, CINAHL (via EBSCO) for healthcare and nursing-specific articles; EMBASE to cover more fields of healthcare; and ERIC (via EBSCO) for literature on further education. Grey literature was also hand searched via the meta-search engine DogPile. The date last searched for the above databases was the 8th of May 2022. The terms used in the search were classified into four themes, health professionals terms such as “Health$professional” or “nurs$”, stigma terms such as “stigma” or “discrimination”, content terms such as “health advocacy” or “social accountability” and delivery terms such as “training” or “curriculum”. MeSH terms were also used for the appropriate databases. Titles and abstracts from 1980 and onwards were searched. The search strategy used was:

“Health professional terms” tw AND (“Intervention terms” adj3 “Stigma terms”) ti

OR

((“Culturally competent care” OR “Cultural competenc*”) adj3 “intervention terms”) ti AND “Health professional terms” tw AND “Stigma terms” tw

OR

(Health professional MESH terms AND Stigma MESH terms AND Intervention MESH terms)

Table 2. Efficacy outcomes

Study selection

In the first stage of screening for abstract and title, two co-reviewers (ZG, BI) screened all of the data independently then discussed conflicts until they reached a mutual agreement. In case of persistent conflict, a third reviewer was consulted (CH). In the second stage of full-text screening, the data were divided in two halves which each co-reviewer (ZG, BI) screened independently. Before screening all data the same two co-reviewers screened 10% of each other’s data set in order to achieve mutual agreement. Conflicts were discussed until mutual agreement was reached, if conflict persisted a third reviewer was consulted (CH).

For the data extraction stage data remained split between two co-reviewers as it was in the full-text screening stage. Data extraction was firstly done for 10% of the data by the same two independent co-reviewers, conflicts were discussed, following which co-reviewers extracted data for their half of the data each.

Data extraction

A bespoke data extraction tool was used. Included studies were classified according to the authors, origin, year of publication, sample characteristics, methods, and main results. For research question 1, data on the theory base, content, and delivery of the programs were collected while, for research question 2, data on effectiveness measures and their outcomes were collected. Outcome measures were categorised based on a definition of stigma as a problem which arises from a lack of knowledge such as ignorance and misinformation, negative attitudes fuelled by prejudices, and excluding or avoiding behaviours, otherwise called discrimination (Thornicroft, Citation2008).

Data synthesis

The data were analysed and synthesized using narrative synthesis (Popay et al., Citation2006). The data were categorized and synthesized based on: the research questions they pertain to; the type of discrimination they address, this was defined via the rationale of each study and the theory base which they employed for example social justice models or human rights models; and finally, the level at which they destigmatize – individual or structural.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was carried out using the ICROMS (Integrated quality Criteria for the Review of Multiple Study designs) tool, however, studies which scored low were not excluded. This was done independently by two co-reviewers on 10% of the papers. This tool was chosen as it is one of the few tools which allows to assess studies of different designs. The ICROMS tool uses a list of seven quality criteria (aims and justifications, sampling bias, bias in measurements and binding, bias in follow-up, bias in other study aspects, analytical rigour, and bias in reporting/ethical considerations). Each criterion is scored according to a scoring matrix which describes the lowest possible score each study design should achieve for inclusion (Zingg et al., Citation2016).

Results

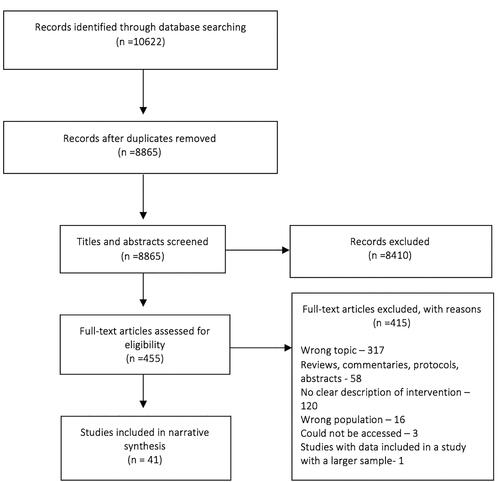

The total number of papers identified was 10,622, and 8865 after removing duplicates, one paper was identified by one of the review authors (CH) as she is the study principal investigator. After the first stage of screening for abstracts and titles, 453 papers were included. After inspection of the full texts of the 455 papers 41 were included for final data extraction. Also, three other papers were not processed in the data extraction stage as they are protocols or descriptive studies but were described as they are of interest for future reference. Most papers excluded at the full-text stage were ineligible because the programs they described were either focusing solely on destigmatizing healthcare professionals and not training them to help their patients, or solely measured attitudes in healthcare professionals. The exclusion reasoning can be seen in the PRISMA flow chart below (Moher et al., Citation2009) ().

The data extracted can be seen in . Most of the studies were done in high-income countries, most in the USA or Canada (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Crawford et al., Citation2017; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015, Citation2020; Jindal et al., Citation2022; Knaak, Citation2018; Lax et al., Citation2019; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; Tucker et al., Citation2020; White-Davis et al., Citation2018; Zäske et al., Citation2014). Four studies included data from middle and low-income countries (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Potts et al., Citation2022; Uys et al., Citation2009) In terms of participants, 24 studies focused on healthcare students, be that nursing or medicine, describing programs added to teaching curriculums at universities (Allen et al., Citation2013; Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Burdett et al., Citation2010; Crawford et al., Citation2017; DallaPiazza et al., Citation2018; DeLashmutt & Rankin, Citation2005; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015, Citation2020; İnan et al., Citation2019; Jones, Citation2000; Jindal et al., Citation2022; Lax et al., Citation2019; Mason & Miller, Citation2006; McAllister, Citation2008; O Carroll & O’Reilly, Citation2019; Potts et al., Citation2022; Shah et al., Citation2014; Sheely-Moore & Kooyman, Citation2011; Tucker et al., Citation2020; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Wagaman et al., Citation2019; Werkmeister Rozas & Garran, Citation2016). A small proportion of studies focused on participants with work experience, such as therapists or specialist mental healthcare staff (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Fisher et al., Citation2017; Fisher-Borne, Citation2009; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Knaak, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2015, Citation2013; Nelson et al., Citation2015; Sherman et al., Citation2019; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; White-Davis et al., Citation2018; Zäske et al., Citation2014).

Quality appraisal

Twelve studies could not be assessed because they did not have an empirical study design. Of the remaining 29, the ICROMS minimum scores were achieved for 14 of the 29 studies. The studies which did not achieve the minimum scores lacked enough information about participant recruitment and sampling, blinding, prevention of detection bias or contamination between groups. See Table S3 in the supplementary material for all ICROMS scores.

Table 3. Acceptability outcomes.

Research question 1 – What are the theory base, content and delivery methods of the programs?

Theory base

Fourteen of the 41 studies included considered the idea that the goals of the program should align with the vision of the curriculum or the role of the professional themselves (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Jones, Citation2000; Jindal et al., Citation2022; Lax et al., Citation2019; Mason & Miller, Citation2006; Sherman et al., Citation2019; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Wagaman et al., Citation2019; Werkmeister Rozas & Garran, Citation2016; White-Davis et al., Citation2018). This means that the programs’ theory base was set on the premise that it is supposed to teach its participants something that should be core to their knowledge in their profession. Another theory used by a single study is the idea of increasing the effectiveness of work (Crawford et al., Citation2017). This also implies that the behaviour, attitudes and skills the program is teaching are integral to the participants’ profession. Some studies focused on actual collaboration and creation of change, either in the communities where the participants work or in collaboration with other healthcare professionals (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Lax et al., Citation2019; Tucker et al., Citation2020).

Eight other studies operated on the premise that healthcare professionals are harming their patients with a lack of skills, thus deepening discrimination (DeLashmutt & Rankin, Citation2005; Potts et al., Citation2022; Knaak, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2015; Nelson et al., Citation2015; O Carroll & O’Reilly, Citation2019; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Zäske et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, some of the interventions are based on the theory that stigma is implicit in all structures of healthcare, and therefore simple programs are no longer enough to impact change, there is a need for healthcare professionals to actively fight against organizational stigma (Allen et al., Citation2013; Geibel et al., Citation2017; İnan et al., Citation2019; McAllister, Citation2008; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2019).

Content

More programs focused on individual discrimination combined with some aspects of structural discrimination rather than solely on structural discrimination. Those which focused on structural stigma often centred around social determinants of health, community health, advocacy, and political action while targeting the idea of the responsibility of the professional (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Crawford et al., Citation2017; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Lax et al., Citation2019). The studies which focused on individual stigma emphasized more needs-based approaches, which were embedded in communication with patients, and targeted individual healthcare professionals’ stigmatizing beliefs (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Knaak, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2015; Potts et al., Citation2022; Zäske et al., Citation2014).

Frequently mentioned concepts were those of social justice knowledge, action, and integration as well as health and human rights (Allen et al., Citation2013; Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Crawford et al., Citation2017; Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Jones & Smith, Citation2014; McAllister, Citation2008; Webb & Sergison, Citation2003). These were operationalized within the limits of the participants’ current or future profession. Specific concepts often mentioned were social determinants of health and discrimination, marginalization of certain groups (Allen et al., Citation2013; Crawford et al., Citation2017; DallaPiazza et al., Citation2018; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Knaak, Citation2018; Lax et al., Citation2019; O’Carroll & O’Reilly, Citation2019). A small proportion of studies focused on stigma specifically, for example, stigma of a specific health condition or racism (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Fisher-Borne, Citation2009; İnan et al., Citation2019; Knaak, Citation2018; Potts et al., Citation2022; Sherman et al., Citation2019; Webb & Sergison, Citation2003; Werkmeister Rozas & Garran, Citation2016; Zäske et al., Citation2014). Some studies focused on the participants’ own biases and actively examining them (Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Knaak, Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2015; Potts et al., Citation2022; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Wagaman et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2019). Three studies also focused on discrimination from the perspective of the patient (Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Zäske et al., Citation2014).

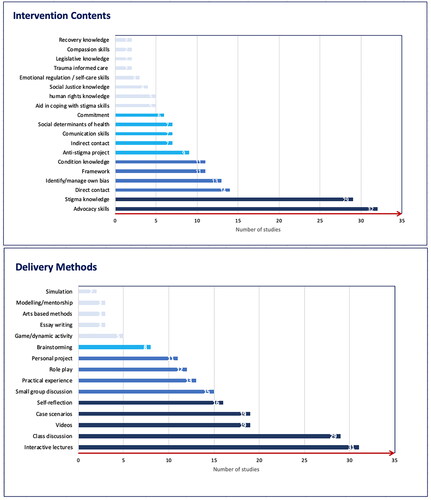

Finally, a large majority of studies focused on teaching correct practices and skills (Allen et al., Citation2013; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Fisher-Borne, Citation2009; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Griffith & Kohrt, Citation2016; İnan et al., Citation2019; Knaak, Citation2018; Lax et al., Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; McAllister, Citation2008; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Webb & Sergison, Citation2003; Wu et al., Citation2019). These can be further categorized as communication skills, the ability to address discrimination in different settings, comfort around topics of stigma, and specific strategies such as defining and working with legislation regarding poverty, human rights activism, screening and referral to appropriate services to mitigate social determinants of health and actively developing projects that address discrimination. Frequencies can be seen in below.

Delivery methods

The length of the programs varied, from hours to days or weeks. Most studies included a component of knowledge transmission (Allen et al., Citation2013; Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; DeLashmutt & Rankin, Citation2005; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; İnan et al., Citation2019; Jindal et al., Citation2022; Knaak, Citation2018; Lax et al., Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2015; Mason & Miller, Citation2006; McAllister, Citation2008; Potts et al., Citation2022; Sherman et al., Citation2019; Sukhera et al., Citation2020; Tucker et al., Citation2020; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018; Uys et al., Citation2009; Wagaman et al., Citation2019; Webb & Sergison, Citation2003; Werkmeister Rozas & Garran, Citation2016; White-Davis et al., Citation2018; Wu et al., Citation2019; Zäske et al., Citation2014). The latter was achieved in several different ways, for example, lecture components on basic facts of discrimination, didactic teaching, a transformative learning approach, roleplays, seminars, workshops, videos, case-based examples. However, some also included more introspective methods of learning such as considering one’s own behaviour and skills through journaling or applying the knowledge learned to own experiences from practice (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Boutain, Citation2008; Crawford et al., Citation2017; Knaak, Citation2018). Applying knowledge in practice was mentioned by a proportion of studies. This most often took the form of working on a project alongside local communities, working with mentors, or training other students in a train-the-trainer approach (Bakshi et al., Citation2015; Dharamsi et al., Citation2010; Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Üstün & İnan, Citation2018). Some studies also included learning from people with lived experience through discussions (Lax et al., Citation2019; Potts et al., Citation2022; Zäske et al., Citation2014). Finally, two studies used an online platform or remote video projection to deliver the program (Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Knaak, Citation2018). Frequencies can be seen in below.

Research question 2 – What is the evidence for the effectiveness and feasibility of the programs?

The results for research question 2 were extracted from 19 studies out of the 41 included and can be seen in below. In general, for all the studies some positive, significant outcomes are reported. About half of the studies show changes in mean scores for measures of attitudes (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; İnan et al., Citation2019; Knaak, Citation2018; Lax et al., Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2015; Potts et al., Citation2022; Tucker et al., Citation2020; Zäske et al., Citation2014). Ten studies show changes in knowledge (Crawford et al., Citation2017; Fisher-Borne, Citation2009; Flatt-Fultz & Phillips, Citation2012; Geibel et al., Citation2017; Gonzalez et al., Citation2015; Knaak, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2015; Nelson et al., Citation2015; Tucker et al., Citation2020; Zäske et al., Citation2014), while only seven show changes in skills (Crawford et al., Citation2017; Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002; Lax et al., Citation2019; Nelson et al., Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2019; Tucker et al., Citation2020; Zäske et al., Citation2014).

However, there is great variability in the scales chosen to assess different components of the programs presented in the studies. Furthermore, not all studies assessed knowledge, attitudes, and skills but rather selected some of these components or specific subsets within these components. Therefore, it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of the studies against each other. Finally, it must be noted that the scales chosen to assess discrimination mostly assessed intended behaviour rather than actual completed actions. Finally, two studies chose to assess the impact on patients by directly measuring patient outcomes (Geibel et al., Citation2017; Uys et al., Citation2009). Detailed efficacy outcomes can be seen in Table S4 in supplementary materials.

Feasibility or acceptability was measured only in six studies, the specific outcomes can be seen in below. Most of the studies report positive outcomes with participants rating the interventions agreeable and acceptable for their practice.

Studies included but not processed for data extraction

There are three studies which were not included in the data extraction stage either because they do not fit the inclusion criteria or because they are protocols. It is important to describe these studies to map possible outcomes in future literature. Firstly, Grandón et al. (Citation2019) describe in their protocol an educational program for healthcare professionals which will focus on educational outcomes and contact with people with lived experience to reduce stigma, as well as promoting inclusive behaviours towards people with severe mental disorders. Secondly, Chenneville, Gabbidon and Drake’s (Citation2019) study describes a program delivered by community healthcare workers to youth living with HIV to destigmatize and educate them about the condition. Through qualitative research Chenneville et al., (Citation2019) found that community healthcare workers delivering the program saw a destigmatizing effect on themselves through teaching the program. This finding would tie into other studies mentioned which also utilize a train-the-trainers approach (Ezedinachi et al., Citation2002). Finally, Maranzan (Citation2016) describes a new learning environment called interprofessional education in which participants learn from other professionals within their field who have experience within the chosen topic. This type of learning could be well suited to learn about and integrate stigma reduction strategies through an open unbiased discussion amongst healthcare professionals.

Discussion

The current study aimed to assess the existing evidence regarding programs targeted at healthcare professionals which aim to not only destigmatize but also to teach healthcare professionals how to address stigma. The search identified 41 studies from which data was extracted. While the programs differed in many aspects, there were some clear themes within each category explored – theory base, content, and delivery methods. In terms of effectiveness, feasibility, and evaluation there are some concerns regarding the methods employed by each study.

The studies included can be considered of varying quality, with some of them being of very low quality. The quality of the studies included in turn impacts the quality of the current study findings. However, because we focused on program content, no studies which scored low in their quality appraisal were excluded, to allow the extraction of such data. We also included papers which did not include program evaluation but instead aimed to describe the programs in detail and explain the rationale for their creation.

Feasibility and evaluation

In most papers, feasibility and evaluation were described as practical approaches to the implementation of interventions. Thus, there is a distinct lack of information on barriers to delivery, or resources needed to implement an intervention. Therefore, we describe feasibility and evaluation as concrete aspects of interventions which allow its implementation.

Firstly, in terms of the feasibility of the programs, it is clear that programs can be delivered to either undergraduates or postgraduate trainees, and there were no clear differences in length or delivery formats between courses for these groups. However, only a small sub-set of programs addressed fully qualified professionals, suggesting that it is harder to reach this group.

Secondly, interventions for postgraduate and fully qualified professionals were found largely in certain specialties such as primary care, where they are tailored to participants’ professional roles. This suggests that some specialties may not yet be widely incorporating health advocacy training even where this has been recommended at the national level (Leveridge et al., Citation2007).

Thirdly, as most of the programs were carried out in high-income countries, the feasibility of such programs in low- and middle-income countries is hard to establish on the basis of the evidence presented. This is also because, as already stated, it is unclear what resources and investments were necessary for the presented interventions in the first place. Furthermore, in different cultures, the needs of patients but also necessary resources may be different, and they may experience stigma in different ways from participants in high-income countries.

In terms of evaluation, very few studies included a pilot stage or a situational analysis to adapt the programs to their contexts. While most studies used a pre-post data collection method, only one conducted a follow-up assessment beyond six weeks. This means that no data on actual behavioural change were collected. Furthermore, as already mentioned no data from patients were collected so the intended impact of the programs could never be directly measured. The findings seem to point to positive outcomes, however, the outcomes that were measured were very variable and therefore it is hard to compare which program was, in fact, more effective. Another factor that complicates the evaluation of the effectiveness of the included studies is that most of them did not effectively link the theory basis or content of the programs to the outcome measures. Therefore, we can only assume implicit theories, such as active learning style may help with knowledge retention regarding discrimination. The above issues could be remedied by a longer follow-up period which would measure actual behavioural changes as well as impacts as perceived by their patients.

Theory base, content and delivery methods

The theory base for most studies could be summarized intro three main foci– responsibility as part of the professional role, correction of wrongful practices, and collaboration with local communities. However, based on previous literature it seems that embedding the program into morals tied to the role of the healthcare professional seems to lead to better long-term changes. Research has suggested that continued professional development for healthcare professions seems to be more effective if embedded into the concept of social accountability and the professional role (Fleet et al., Citation2008).

With regard to the content of the programs, there seems to be a split between focusing on broad topics such as social determinants of health versus stigma towards a particular health condition. Broad concepts such as the social determinants of health can be limiting, as they are harder to define or operationalize for training purposes. However, such concepts also invite a much larger conversation which can lead to programs which address the societal structures of stigma. On the contrary, programs which focus on specific mental health disorders invite a more in-depth analysis of the needs of patients with such disorders. They remain tied to a smaller community and may be preferable for more specialized healthcare professionals. Nevertheless, either of these approaches allow the introduction of the spectrum of social accountability and the “fit” between a particular issue and the level (micro, meso, or macro) at which it would best be addressed (Bernard et al., Citation2019).

Few studies focus on addressing the participants’ biases and stigma directly, rather they educate without assessing the initial levels of discrimination participants may hold. However, realizing one’s own bias may consist of an education outcome in and of itself (Menatti et al., Citation2012). Further, while all the studies provide their participants with some methods on how to combat stigma, not as many provide specific methods and skills. This is especially important when needing to address structural stigma as this can be a challenge for which healthcare professionals are not prepared. Finally, few studies chose to mention patient perspectives, be that in designing the program or in its content. Very few papers focus on the concept of self-stigma with only a few interventions implementing components of empowerment of people with lived experience. This is a gap in the literature that further ties to the lack of patient perspectives in interventions for the healthcare professional. However, when it comes to experiences of stigma people with lived experience should be considered the experts. Moreover, adapting the program to the needs of the patients would increase its effectiveness. For example, community-based participatory research has often been shown to be an effective way to create programs which are suited to the needs of vulnerable communities (Stacciarini et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, the creation of a program which does not include people with lived experience input could be considered stigmatizing in and of itself. Without this input, programs which teach healthcare professionals to combat the stigma which their patients experience could easily become paternalistic in their rhetoric.

Regarding delivery methods, while all programs used active learning as a key component, the way in which this was delivered differed. Several studies also lead to the application of the knowledge learned in projects or real-life settings mediated for example via roleplays. Previous research on microaggressions in the classroom setting suggests “the advantage of discussion” is the opportunity for “the ambiguous nature of microaggressions be elucidated for those that may not be aware that bias has occurred” (Boysen, Citation2012). This is especially useful as subtle forms of stigma are common and many times unnoticed in health professionals (e.g. over protectionist behaviour, lower educational expectations) (Mason & Miller, Citation2006).

Perhaps most interestingly, some programs required students to work with communities and create long-lasting projects. This meant that not only did the program train the participants but also contributed actively towards destigmatisation.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is its breadth of coverage, due to the range of databases used and the inclusion of undergraduate and postgraduate trainees and fully qualified professionals across the health professions. However, the review is nonetheless vulnerable to publication bias. The studies included describe programs with positive outcomes, it is very likely that programs or versions of the programs included which did not work were not published. The current study also did not use meta-analysis to analyse the data. This is primarily because of the differences between study designs, populations assessed, and programs. However, the chosen narrative synthesis allows for a robust analysis of the data. Another limitation of this study is the fact that the stages of full-text screening and data extraction were done by only one reviewer for most papers due to the division of the data set after 10% of each half was discussed among co-reviewers.

Conclusions

The reason for undertaking the current study was to inform the development of a program to focus on mental health stigma and how mental health professionals can reduce it. First, the program should be based on theories encompassing both the structural and individual levels. It should contain clear definitions of structural and individual-level stigma and operationalize it using data to show the impacts on patients. Second, it should draw on the idea of the professional role of healthcare providers and their professional accountability. Third, in terms of the inclusion of people with lived experience, there is a need to work alongside vulnerable communities and individuals. For example, Schwartz (Citation2002) outlines that for such cooperation to happen there is a need to have clear guidelines for both the practice and education of healthcare professionals. Regarding some of the programs, there is also a risk that communities may end up feeling exploited. Program participants may gain the impression that projects and collaborations are being done in a sense of optical allyship – meaning that the programs are done in a tokenistic fashion to simply achieve an outcome imposed by current trends or societal pressure. On the other hand, there is a risk of an overly protective stance on the part of professionals, as a result of trying to shield patients from the stigma which reduces their social and economic opportunities. Healthcare professionals’ programs should therefore focus on empowering rather than protecting patients, in both the process of program development and the program content. Moreover, since the impacts of stigma can be seen in social determinants of health, healthcare professionals working with vulnerable populations will need to learn more specific skills in relation to such determinants, such as advocacy for economic stability or educational achievements. Skills such as capacity building may therefore be suitable for such situations.

In order to offer all the above qualities, the studies should improve their research designs and inclusion of people with lived experience. Situational analysis and piloting would ensure that the program is sufficiently tailored to the healthcare professionals’ setting as well as their patients’ context. Secondly, there is a need to identify a theory to achieve modelling of how the program and works to achieve its intended outcomes. Thirdly, the program should be tailored to the participants’ context which means assessing the feasibility, acceptability, sustainability, and perceived effectiveness of the program. Studies should aim to use rigorous study designs including longer follow-up periods (Craig et al., Citation2008), and assess skills rather than intended behaviour. Lastly, studies should try to include measures of the direct impact on patients.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (84.5 KB)Acknowledgments

Thank you to Selin Oturaklı, Sakina Hassani and Ma Ning for their kind translation of the studies in Turkish, Persian and Chinese respectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Sstatement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrams, L. S., & Moio, J. A. (2009). Critical race theory and the cultural competence dilemma in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2009.200700109

- ACGME. (2007). Common program requirements 2007. http://www.Acgme.Org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_04012007.Pdf.

- Allen, J., Brown, L., Duff, C., Nesbitt, P., & Hepner, A. (2013). Development and evaluation of a teaching and learning approach in cross-cultural care and antidiscrimination in university nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 33(12, 1592–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.12.006

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Perseus Book.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2008). The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. Retrieved from https://www.aacnnursing.org/portals/42/publications/baccessentials08.pdf

- Arboleda-Flórez, J., & Stuart, H. (2012). From sin to science: Fighting the stigmatization of mental illnesses. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(8), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700803

- Arredondo, P., Toporek, R., Brown, S. P., Jones, J., Locke, D. C., Sanchez, J., & Stadler, H. (1996). Operationalization of the multicultural counseling competencies. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 24(1), 42–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.1996.tb00288.x

- Bakshi, S., James, A., Hennelly, M. O., Karani, R., Palermo, A.-G., Jakubowski, A., Ciccariello, C., & Atkinson, H. (2015). The human rights and social justice scholars program: A collaborative model for preclinical training in social medicine. Annals of Global Health, 81(2), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.04.001

- Baum, F. (2011). The New Public Health, 3rd edition. Sydney Australia: Oxford University Press.

- Bates, L., & Stickley, T. (2013). Confronting Goffman: How can mental health nurses effectively challenge stigma? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(7), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01957.x

- Bernard, C., Soklaridis, S., Paton, M., Fung, K., Fefergrad, M., Andermann, L., Johnson, A., Ferguson, G., Iglar, K., & Whitehead, C. R. (2019). Family physicians and health advocacy: Is it really a difficult fit? Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 65(7), 491–496.

- Boutain, D. M. (2008). Social justice as a framework for undergraduate community health clinical experiences in the United States. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 5(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1419

- Boysen, G. A. (2012). Teacher and student perceptions of microaggressions in college classrooms. College Teaching, 60(3), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2012.654831

- Bratbo, J., & Vedelsby, A. K. (2017). ONE OF US: The national campaign for anti-stigma in Denmark. In W. Gaebel, W. Rossler, N. Sartorius (Eds.). The stigma of mental illness - end of the story? Springer International Publishing.

- Brigham, T. M. (1977). Liberation in social work education: Applications from Paulo Freire. Journal of Education for Social Work, 13(3), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220612.1977.10671449

- Buchman, S., Woollard, R., Meili, R., & Goel, R. (2016). Practising social accountability: From theory to action. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 62(1), 15–18.

- Burdett, J., Tremayne, P., & Utecht, C. (2010). How to make care champions. Nursing Older People, 22(2), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2010.03.22.2.26.c7566

- Campinha-Bacote, J. (1999). A model and instrument for addressing cultural competence in health care. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(5), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-19990501-06

- Carrara, B. S., Ventura, C. A. A., Bobbili, S. J., Jacobina, O. M. P., Khenti, A., & Mendes, I. A. C. (2019). Stigma in health professionals towards people with mental illness: An integrative review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(4), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.006

- Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018854

- Chenneville, T., Gabbidon, K., & Drake, H. (2019). The HIV SEERs Project: A Qualitative Analysis of Program Facilitators’ Experience. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 18, 2325958218822308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325958218822308

- Corrigan, P. W., Mittal, D., Reaves, C. M., Haynes, T. F., Han, X., Morris, S., & Sullivan, G. (2014). Mental health stigma and primary health care decisions. Psychiatry Research, 218(1–2), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.028

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Crawford, E., Aplin, T., & Rodger, S. (2017). Human rights in occupational therapy education: A step towards a more occupationally just global society. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12321

- Cross, H., & Choudhary, R. (2005). STEP: An intervention to address the issue of stigma related to leprosy in Southern Nepal. Leprosy Review, 76(4), 316–324.

- DallaPiazza, M., Padilla-Register, M., Dwarakanath, M., Obamedo, E., Hill, J., & Soto-Greene, M. L. (2018). Exploring racism and health: An intensive interactive session for medical students. MedEdPORTAL, 14(1), 10783. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10783

- DeLashmutt, M. B., & Rankin, E. A. (2005). A different kind of clinical experience. Nurse Educator, 30(4), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200507000-00005

- Dharamsi, S., Richards, M., Louie, D., Murray, D., Berland, A., Whitfield, M., & Scott, I. (2010). Enhancing medical students’ conceptions of the CanMEDS Health Advocate Role through international service-learning and critical reflection: A phenomenological study. Medical Teacher, 32(12), 977–982. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903394579

- Ezedinachi, E., Ross, M., Meremiku, M., Essien, E., Edem, C., Ekure, E., & Ita, O. (2002). The impact of an intervention to change health workers’ HIV/AIDS attitudes and knowledge in Nigeria. Public Health, 116(2), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ph.1900834

- Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Kebede, D., Alem, A., Cleare, A. J., Prince, M., Hanlon, C., & Shibre, T. (2015). Excess mortality in severe mental illness: 10-year population-based cohort study in rural Ethiopia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149112

- Fisher, A. K., Moore, D. J., Simmons, C., & Allen, S. C. (2017). Teaching social workers about microaggressions to enhance understanding of subtle racism. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2017.1289877

- Fisher-Borne, M. M. (2009). The design, implementation and evaluation of a statewide cultural competency training for North Carolina Disease Intervention Specialists. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Flatt-Fultz, E., & Phillips, L. A. (2012). Empowerment training and direct support professionals’ attitudes about individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 16(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629512443652

- Fleet, L. J., Kirby, F., Cutler, S., Dunikowski, L., Nasmith, L., & Shaughnessy, R. (2008). Continuing professional development and social accountability: A review of the literature. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 22(Suppl 1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802028360

- Frank, J. R., Snell, L., Sherbino, J. (2015). CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

- Friedrich, B., Evans-Lacko, S., London, J., Rhydderch, D., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Anti-stigma training for medical students: The Education Not Discrimination project. British Journal of Psychiatry, 55, s89–s94. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.114017

- Geibel, S., Hossain, S. M. I., Pulerwitz, J., Sultana, N., Hossain, T., Roy, S., Burnett-Zieman, B., Stackpool-Moore, L., Friedland, B. A., Yasmin, R., Sadiq, N., & Yam, E. (2017). Stigma reduction training improves healthcare provider attitudes toward, and experiences of, young marginalized people in Bangladesh. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), S35–S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.026

- Goel, R., Buchman, S., Meili, R., & Woollard, R. (2016). Social accountability at the micro level: One patient at a time. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 62(4), 287–290.

- Gonzalez, C. M., Fox, A. D., & Marantz, P. R. (2015). The evolution of an elective in health disparities and advocacy. Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1636–1640. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000850

- Gonzalez, C. M., Walker, S. A., Rodriguez, N., Karp, E., & Marantz, P. R. (2020). It can be done! A skills-based elective in implicit bias recognition and management for preclinical medical students. Academic Medicine, 95(12S), S150–S155. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003697

- Grandón, P., Saldivia, S., Vaccari, P., Ramirez-Vielma, R., Victoriano, V., Zambrano, C., Ortiz, C., & Cova, F. (2019). An integrative program to reduce stigma in primary healthcare workers toward people with diagnosis of severe mental disorders: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00110

- Griffith, J. L., & Kohrt, B. A. (2016). Managing stigma effectively: What social psychology and social neuroscience can teach us. Academic Psychiatry, 40(2), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0391-0

- Henderson, C., Noblett, J., Parke, H., Clement, S., Caffrey, A., Gale-Grant, O., Schulze, B., Druss, B., & Thornicroft, G. (2014). Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(6), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6

- Hocking, C., Townsend, E. L., & Mace, J. (2021). World federation of occupational therapists position statement: Occupational therapy and human rights (Revised 2019) – the backstory and future challenges. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 78, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2021.1915608

- İnan, F. Ş., Günüşen, N., Duman, Z. Ç., & Ertem, M. Y. (2019). The impact of mental health nursing module, clinical practice and an anti-stigma program on nursing students’ attitudes toward mental illness: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(3), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.10.001

- Jindal, M., Mistry, K. B., McRae, A., Unaka, N., Johnson, T., & Thornton, R. L. (2022). It makes me a better person and doctor”: A qualitative study of residents’ perceptions of a curriculum addressing racism. Academic Pediatrics, 22(2), 332–341.

- Jones, C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1212–1215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212

- Jones, M., & Smith, P. (2014). Population-focused nursing: Advocacy for vulnerable populations in an RN-BSN program. Public Health Nursing, 31(5), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12114

- Knaak, S. (2018). Destigmatizing Practices and Mental Illness’ online program for nurses and allied health providers: Evaluation report.

- Kratzke, C., & Bertolo, M. (2013). Enhancing students’ cultural competence using cross-cultural experiential learning. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 20(3), 107–111.

- Kugathasan, P., Horsdal, H. T., Aagaard, J., Jensen, S. E., Laursen, T. M., & Nielsen, R. E. (2018). Association of secondary preventive cardiovascular treatment after myocardial infarction with mortality among patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(12), 1234–1240. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2742

- Larson, G. (2008). Anti-oppressive practice in mental health. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 19(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428230802070223

- Lax, Y., Braganza, S., & Patel, M. (2019). Three-tiered advocacy: Using a longitudinal curriculum to teach pediatric residents advocacy on an individual, community, and legislative level. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 6, 2382120519859300. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519859300

- Le Boutillier, C., Leamy, M., Bird, V. J., Davidson, L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1470–1476. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.001312011

- Lee, C. (2018). Counseling for social justice. (2nd ed.). American Counselling Association.

- Leininger, M., & McFarland, M. (2002). Transcultural nursing concepts, theories, research and practice (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Leveridge, M., Beiko, D., Wilson, J. W. L., & Siemens, D. R. (2007). Health advocacy training in urology: A Canadian survey on attitudes and experience in residency. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 1(4), 363–369. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.438

- Li, L., Lin, C., Guan, J., & Wu, Z. (2013). Implementing a stigma reduction intervention in healthcare settings. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(3 Suppl 2), 18710. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.3.18710

- Li , Li, J., Thornicroft, G., Yang, H., Chen, W., & Huang, Y. (2015). Training community mental health staff in Guangzhou, China: evaluation of the effect of a new training model. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0660-1

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Liu, N. H., Daumit, G. L., Dua, T., Aquila, R., Charlson, F., Cuijpers, P., Druss, B., Dudek, K., Freeman, M., Fujii, C., Gaebel, W., Hegerl, U., Levav, I., Munk Laursen, T., Ma, H., Maj, M., Elena Medina-Mora, M., Nordentoft, M., Prabhakaran, D., & Saxena, S. (2017). Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: A multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20384

- Maranzan, K. A. (2016). Interprofessional education in mental health: An opportunity to reduce mental illness stigma. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1146878

- Mason, S. E., & Miller, R. (2006). Stigma and schizophrenia. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 26(1–2), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v26n01_05

- McAllister, M. (2008). Looking below the surface: Developing critical literacy skills to reduce the stigma of mental disorders. Journal of Nursing Education, 47(9), 426–430. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20080901-06

- Mehta, N., Clement, S., Marcus, E., Stona, A.-C., Bezborodovs, N., Evans-Lacko, S., Palacios, J., Docherty, M., Barley, E., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(5), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.151944

- Meili, R., Buchman, S., Goel, R., & Woollard, R. (2016). Social accountability at the macro level: Framing the big picture. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 62(10), 785–788.

- Menatti, A., Smyth, F., Teachman, A. B., Nosek, A. B. (2012). Reducing stigma toward individuals with mental illnesses: A brief, online intervention. Stigma Research and Action.

- Mitchell, A. J., Malone, D., & Doebbeling, C. C. (2009). Quality of medical care for people with and without comorbid mental illness and substance misuse: systematic review of comparative studies. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(6), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045732

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Nelson, S. C., Prasad, S., & Hackman, H. W. (2015). Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(5), 915–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25448

- O Carroll, A., & O’Reilly, F. (2019). Medicine on the margins. An innovative GP training programme prepares GPs for work with underserved communities. Education for Primary Care, 30(6), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2019.1670738

- Perry, A., Lawrence, V., & Henderson, C. (2020). Stigmatisation of those with mental health conditions in the acute general hospital setting. A qualitative framework synthesis. Social Science & Medicine, 255, 112974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112974

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

- Potts, L. C., Bakolis, I., Deb, T., Lempp, H., Vince, T., Benbow, Y., & Henderson, C. (2022). Anti-stigma training and positive changes in mental illness stigma outcomes in medical students in ten countries: A mediation analysis on pathways via empathy development and anxiety reduction. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(9), 1861–1873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02284-0

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (2011). CanMEDS: Better standards, better physicians, better care.

- Sartorius, N. (1998). Stigma: What can psychiatrists do about it? The Lancet, 352(9133), 1058–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08008-8

- Schulze, B. (2007). Stigma and mental health professionals: A review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278929

- Schutz, S. (2007). Reflection and reflective practice. Community Practitioner, 80(9), 26–29.

- Schwartz, L. (2002). Is there an advocate in the house? The role of health care professionals in patient advocacy. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28(1), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.28.1.37

- Sensoy, Ö., & DiAngelo, R. (2012). Is everyone really equal?:An introduction to key concepts in social justice education. Teachers College Press.

- Shah, S. M., Heylen, E., Srinivasan, K., Perumpil, S., & Ekstrand, M. L. (2014). Reducing HIV stigma among nursing students. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 36(10), 1323–1337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914523685

- Shaws, E., Oandasan, I., Fowler, N. C. F. (2017). CanMEDS 2017: A competency framework for family physicians across the continuum. The College of Family Physicians of Canada.

- Sheely-Moore, A. I., & Kooyman, L. (2011). Infusing multicultural and social justice competencies within counseling practice: A guide for trainers. Adultspan Journal, 10(2), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0029.2011.tb00129.x

- Sherman, M. D., Ricco, J., Nelson, S. C., Nezhad, S. J., & Prasad, S. (2019). Implicit bias training in residency program: Aiming for enduring effects. Family Medicine, 51(8), 677–681. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.947255

- Stacciarini, J.-M R., Shattell, M. M., Coady, M., & Wiens, B. (2011). Review: Community-based participatory research approach to address mental health in minority populations. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(5), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9319-z

- Stuart, H., Chen, S.-P., Christie, R., Dobson, K., Kirsh, B., Knaak, S., Koller, M., Krupa, T., Lauria-Horner, B., Luong, D., Modgill, G., Patten, S. B., Pietrus, M., Szeto, A., & Whitley, R. (2014). Opening minds in Canada: Background and rationale. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(10 suppl), S8–S12. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901S04

- Sue, D. W., Lin, A. I., Torino, G. C., Capodilupo, C. M., & Rivera, D. P. (2009). Racial microaggressions and difficult dialogues on race in the classroom. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014191

- Sukhera, J., Miller, K., Scerbo, C., Milne, A., Lim, R., & Watling, C. (2020). Implicit stigma recognition and management for health professionals. Academic Psychiatry, 44(1), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01133-8

- Teal, C. R., Shada, R. E., Gill, A. C., Thompson, B. M., Frugé, E., Villarreal, G. B., & Haidet, P. (2010). When best intentions aren’t enough: Helping medical students develop strategies for managing bias about patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(S2), S115–S118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1243-y

- Thornicroft, G. (2008). Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 17(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00002621

- Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., O’Reilly, C., & Henderson, C. (2016). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. The Lancet, 387(10023), 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6

- Thornicroft, G., Rose, D., & Mehta, N. (2010). Discrimination against people with mental illness: What can psychiatrists do? Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004481

- Tucker, J. R., Seidman, A. J., Van Liew, J. R., Streyffeler, L., Brister, T., Hanson, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Effect of contact-based education on medical student barriers to treating severe mental illness: A non-randomized, controlled trial. Academic Psychiatry, 44(5), 566–571.

- Ungar, T., Knaak, S., & Szeto, A. C. (2016). Theoretical and practical considerations for combating mental illness stigma in health care. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9910-4

- Üstün, B., & İnan, F. Ş. (2018). Example of psychiatric nursing practice: Antistigma education program. Journal of Education and Research in Nursing, 15(2), 131. https://doi.org/10.5222/HEAD.2018.131

- Uys, L., Chirwa, M., Kohi, T., Greeff, M., Naidoo, J., Makoae, L., Dlamini, P., Durrheim, K., Cuca, Y., & Holzemer, W. L. (2009). Evaluation of a health setting-based stigma intervention in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(12), 1059–1066. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0085

- Wagaman, M. A., Odera, S. G., & Fraser, D. v. (2019). A pedagogical model for teaching racial justice in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(2), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1513878

- Wahlbeck, K., Westman, J., Nordentoft, M., Gissler, M., & Laursen, T. M. (2011). Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: Life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100

- Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E., & Druss, B. G. (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(4), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502

- Webb, E., & Sergison, M. (2003). Evaluation of cultural competence and antiracism training in child health services. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(4), 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.88.4.291

- Werkmeister Rozas, L., & Garran, A. M. (2016). Towards a human rights culture in social work education. British Journal of Social Work, 46(4), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv032

- White-Davis, T., Edgoose, J., Brown Speights, J. S., Fraser, K., Ring, J. M., Guh, J., & Saba, G. W. (2018). Addressing racism in medical education. Family Medicine, 50(5), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.875510

- Woollard, R., Buchman, S., Meili, R., Strasser, R., Alexander, I., & Goel, R. (2016). Social accountability at the meso level: Into the community. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 62(7), 538–540.

- Wright, C. J., Katcher, M. L., Blatt, S. D., Keller, D. M., Mundt, M. P., Botash, A. S., & Gjerde, C. L. (2005). Toward the development of advocacy training curricula for pediatric residents: A national delphi study. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 5(3), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1367/A04-113R.1

- Wu, D., Saint-Hilaire, L., Pineda, A., Hessler, D., Saba, G. W., Salazar, R., & Olayiwola, N. (2019). The efficacy of an antioppression curriculum for health professionals. Family Medicine, 51(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.227415

- Zäske, H., Freimüller, L., Wölwer, W., & Gaebel, W. (2014). Antistigma-Kompetenz in der psychiatrischen Versorgung: Ergebnisse der Pilotierung einer berufsgruppenübergreifenden Weiterbildung. Fortschritte Der Neurologie Psychiatrie, 82(10), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1385130

- Zingg, W., Castro-Sanchez, E., Secci, F. V., Edwards, R., Drumright, L. N., Sevdalis, N., & Holmes, A. H. (2016). Innovative tools for quality assessment: Integrated quality criteria for review of multiple study designs (ICROMS). Public Health, 133, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.10.012