The World Health Organization has defined mental health as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes their own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and is able to make a contribution to their community (World Health Organisation, Citation2022).

What would it take to create a world where this aspiration of mental health for all is realised? We suggest that it requires a paradigm shift, towards a multifaceted strategy that prioritizes prevention and health promotion, as well as treatment (Patel et al., Citation2018). Universal approaches that target the underlying determinants of health in the whole population have the potential to reduce the prevalence and burden of ill health and ensure more of the population enjoy healthy life expectancy (Rose, Citation1992/2008). There are compelling reasons to focus prevention in childhood and adolescence, because it is a period of significant developmental change and where the precursors for mental ill health in adulthood first appear (Sawyer et al., Citation2012; Natividad et al., Citation2023; Jung, Citation2021).

A promising approach to mental health promotion in adolescence is school-based social-emotional learning (SEL). Universal schools-based interventions “(a) have the potential to contribute to adaptive coping/resilience across an array of experiences and settings, (b) are positively framed and provided independent of risk status, and therefore non-stigmatizing, and (c) may reduce or prevent multiple behaviour problems that are predicted by shared or common risk factors” (Greenberg & Abenavoli, Citation2017). Individual studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest SEL programmes are promising, but consistently note heterogeneity, limitations in study design as well as inadequate attention to diversity, accessibility and implementation, plus call for adequately powered and rigorously designed trials (Beukema et al., Citation2022; Dray et al., Citation2017; Dunning et al., Citation2022).

We recently published the MYRIAD study, a cluster randomized controlled trial (85 schools, 8376 adolescents, aged 11–16) of a teacher-led, school-based mindfulness training intervention compared with established best practice (Kuyken et al., Citation2022a). This study suggested no superiority of the intervention over current good practice on our student mental health outcomes. Our study is not an outlier; a number of adequately powered and designed studies have failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of school-based mental health interventions, ranging from mental health literacy education for teachers to cognitive-behavioural therapy and mindfulness training (Andrews et al., Citation2022; Kidger et al., Citation2021; Stallard et al., Citation2013). We argue that these studies can teach us a great deal in terms of intervention development, research, and implementation.

What are the lessons learned?

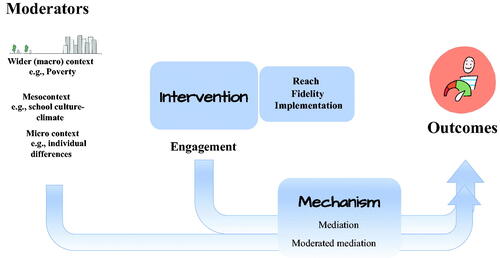

Interventions should articulate their proposed mechanisms of action, and state how the curriculum facilitates changes in mechanisms. Ideally, studies should include a conceptual model that can be explored in process research to make sense of findings and shape the next phase of innovation and research (see ). In our study, a scoping review enabled us to articulate a conceptual model (Tudor et al., Citation2022), which in turn enabled us to explore moderators, mediators and implementation (Montero-Marin et al., Citation2022).

Interventions should target, or at least consider, the macro, meso and individual factors that shape young people’s mental health or moderate the intervention’s acceptability, effectiveness, and implementation. It is perhaps obvious to state that mental health is powerfully shaped by a broad range of factors at macro (e.g. socio-economic status and inequalities), meso (e.g. peer relationships, school climate and home environment) and individual (e.g. age, developmental stage, sex) levels. A conceptual model can consider these factors and crucially outline mechanisms through which they might affect an intervention’s effectiveness. This would inform hypotheses about whether the factors targeted by an intervention would have an interactive, additive, or even multiplicative effect on outcomes. Moreover, it may be that some factors are conditional for benefits to be realised. Findings from the MYRIAD study suggest that mindfulness training may lead to benefits for some young people (e.g. older adolescents), and be ineffective or indeed harmful for others (e.g. those with more mental health symptomatology) (Montero-Marin et al., Citation2022). Several consensus statements propose that universal social-emotional education in schools should sit alongside bespoke mental health children’s services and be fully integrated with wider systemic interventions targeting meso and macro levels (Mahoney et al., Citation2021).

Reach and student engagement are key. It does not matter how well designed an intervention is if it does not reach and engage young people. Intervention design must include careful attention to implementation to maximise both. In MYRIAD, we had excellent reach but poor engagement, which exploratory analyses suggests may partially explain the null finding (Montero-Marin et al., Citation2022). It is also possible for an intervention to engage young people but have poor reach. If a school-based intervention is not be engaging or beneficial to all, then rather than implementing the intervention universally, it may be more appropriate to give students options and choices of approaches that promote mental health.

Co-design interventions with young people. Any intervention needs to speak to adolescents’ concerns, preferences and ways of learning (Yeager et al., Citation2018). In secondary analyses of the MYRIAD trial, adolescents shared a range of views of the intervention (e.g. “I can’t do it,” “boring”) which may go some way to explaining low engagement (Montero-Marin et al, Citationin press). Co-design with the target population is likely to maximise the chance that the intervention is accessible, engaging, and effective. Codesign must include young people from the whole spectrum of the school community as partners, to ensure the range of perspectives and experiences are reflected and designed into the intervention. For example, such co-design has suggested peer-led programs, where older students teach younger students, with promising evidence of effectiveness (e.g. Booth et al. Citation2023; King & Fazel, Citation2021).

The role of schools in young people’s mental health. Schools account for only a small amount of the variation in young people’s mental health (Ford et al., 2021). Thus, school-based interventions should focus on where the evidence suggests they can make a real difference. Secondary analysis of the MYRIAD study converges with other work to suggest that creating a positive school climate could protect mental health (Hinze et al., Citationunder review; Montero-Marin et al., Citationunder review).

Design interventions with implementation in mind. Schools are complex environments facing many competing demands. There is an extensive literature on implementation of social emotional education into schools. Attention to implementation is essential to ensure an intervention is integrated into practice, but can also amplify its effectiveness (Durlak & DuPre, Citation2008).

A key implementation issue is who should deliver interventions. Our work adds to the evidence that translating mental health interventions into classroom curricula is difficult and that while schoolteachers are embedded in schools and know the students, they may not be best placed to deliver SEL interventions. Teachers have many demands on their time and supporting them to teach specialist social-emotional strategies requires considerable training and support (Montero-Marin et al., Citation2021). There is a risk of adding to pressure on teachers, who already report high levels of work stress. Instead, specialist mental health practitioners could to work alongside school teachers (e.g. Shinde et al., Citation2020), and include a whole school approach that includes supporting teachers’ mental health MYRIAD and numerous other studies have shown that such programs can enhance teachers’ mental health, reduce burn out and address retention (Iancu et al., Citation2018; Kuyken et al., Citation2022b).

Finally, any intervention needs, in the context of all the considerations above, to balance reach, engagement, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and risk. These considerations need to be weighed and piloted to determine the optimal intervention design and implementation. Some interventions, for example, may optimise reach and sustainable implementation, but may limit likely effectiveness and engagement (Greenberg & Abenavoli, Citation2017) ().

If WHO’s vision of mental health for all is to be realised, we need specific pathways to that vision, with concrete steps and learning from what works, but also what does not work. School-based approaches to mental health promotion have much promise. We offer these lessons to support researchers, those developing interventions and those shaping policy.

Acknowledgements

JMM has a “Miguel Servet” research contract from the ISCIII (CP21/00080). JMM is grateful to the CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP CB22/02/00052; ISCIII) for its support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrews, J. L., Birrell, L., Chapman, C., Teesson, M., Newton, N., Allsop, S., McBride, N., Hides, L., Andrews, G., Olsen, N., Mewton, L., & Slade, T. (2022). Evaluating the effectiveness of a universal eHealth school-based prevention programme for depression and anxiety, and the moderating role of friendship network characteristics. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291722002033

- Beukema, L., de Winter, A. F., Korevaar, E. L., Hofstra, J., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2022). Investigating the use of support in secondary school: The role of self-reliance and stigma towards help-seeking. Journal of Mental Health, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2022.2069720

- Booth, A., Doyle, E., & O’Reilly, A. (2023). School-based health promotion to improve mental health literacy: a comparative study of peer- versus adult-led delivery. Journal of Mental Health, 32(1), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.2022621

- Dray, J., Bowman, J., Campbell, E., Freund, M., Wolfenden, L., Hodder, R. K., McElwaine, K., Tremain, D., Bartlem, K., Bailey, J., Small, T., Palazzi, K., Oldmeadow, C., & Wiggers, J. (2017). Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

- Dunning, D., Tudor, K., Radley, L., Dalrymple, N., Funk, J., Vainre, M., Ford, T., Montero-Marin, J., Kuyken, W., & Dalgleish, T. (2022). Do mindfulness-based programmes improve the cognitive skills, behaviour and mental health of children and adolescents? An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 25(3), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300464

- Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3-4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10464-008-9165-0

- Ford, T., Degli Esposti, M., Crane, C., Taylor, L., Montero-Marín, J., Blakemore, S.-J., Bowes, L., Byford, S., Dalgleish, T., Greenberg, M. T., Nuthall, E., Phillips, A., Raja, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Viner, R. M., Williams, J. M. G., Allwood, M., Aukland, L., Casey, T., … Kuyken, W, MYRIAD Team. (2021). The role of schools in early adolescents’ mental health: Findings From the MYRIAD Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(12), 1467–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.02.016

- Greenberg, M. T., & Abenavoli, R. (2017). Universal interventions: Fully exploring their impacts and potential to produce population-level impacts. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(1), 40–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1246632

- Hinze, V., Montero-Marin, J., Blakemore, S.J., Byford, S., Dalgleish, T., Degli Esposti, M., Greenberg, M., Jones, B., Slaghekke, Y., Ukoumunne, O.C., Viner, R.M., Williams, J.M.G., Ford, T., & Kuyken, W. (Under Review). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

- Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9420-8

- Jung, J. H. (2021). Do positive reappraisals moderate the association between childhood emotional abuse and adult mental health? Journal of Mental Health, 30(3), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1875411

- Kidger, J., Turner, N., Hollingworth, W., Evans, R., Bell, S., Brockman, R., Copeland, L., Fisher, H., Harding, S., Powell, J., Araya, R., Campbell, R., Ford, T., Gunnell, D., Murphy, S., & Morris, R. (2021). An intervention to improve teacher well-being support and training to support students in UK high schools (the WISE study): A cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS Medicine, 18(11), e1003847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003847

- King, T., & Fazel, M. (2021). Examining the mental health outcomes of school-based peer-led interventions on young people: A scoping review of range and a systematic review of effectiveness. PLOS One, 16(4), e0249553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249553

- Kuyken, W., Ball, S., Crane, C., Ganguli, P., Jones, B., Montero-Marin, J., Nuthall, E., Raja, A., Taylor, L., Tudor, K., Viner, R. M., Allwood, M., Aukland, L., Dunning, D., Casey, T., Dalrymple, N., De Wilde, K., Farley, E.-R., Harper, J., … Williams, J. M. G. (2022a). Effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision on teacher mental health and school climate: Results of the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 25(3), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300424

- Kuyken, W., Ball, S., Crane, C., Ganguli, P., Jones, B., Montero-Marin, J., Nuthall, E., Raja, A., Taylor, L., Tudor, K., Viner, R. M., Allwood, M., Aukland, L., Dunning, D., Casey, T., Dalrymple, N., De Wilde, K., Farley, E.-R., Harper, J., … Williams, J. M. G. (2022b). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: The MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 25(3), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2021-300396

- Mahoney, J. L., Weissberg, R. P., Greenberg, M. T., Dusenbury, L., Jagers, R. J., Niemi, K., Schlinger, M., Schlund, J., Shriver, T. P., VanAusdal, K., & Yoder, N. (2021). Systemic social and emotional learning: Promoting educational success for all preschool to high school students. The American Psychologist, 76(7), 1128–1142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000701

- Montero-Marin, J., Hinze, V., Crane, C., Dalrymple, N., Kempnich, M., Lord, L., Slaghekke, Y., Tudor, K., The MYRIAD Team., Byford, S., Dalgleish, T., Ford T., Greenberg, M.T., Ukoumunne, O., Williams, J.M.G., & Kuyken, W. (In Press). Do adolescents like school-based mindfulness training? Predictors of mindfulness practice and responsiveness in the MYRIAD trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

- Montero-Marin, J., Hinze, V., Mansfield, K., Slaghekke, Y., Blakemore, S.J., Byford, S., Dalgleish, T., Greenberg, M.T., Viner, R.M., Ukoumunne, O.C., Ford, T., & Kuyken, W. (Under Review). Young people’s changes in mental health through a universal stressor - the Covid-19 global pandemic: predictors of positive and negative adjustment. JAMA Pediatrics.

- Montero-Marin, J., Allwood, M., Ball, S., Crane, C., De Wilde, K., Hinze, V., Jones, B., Lord, L., Nuthall, E., Raja, A., Taylor, L., Tudor, K., Blakemore, S.-J., Byford, S., Dalgleish, T., Ford, T., Greenberg, M. T., Ukoumunne, O. C., Williams, J. M. G., & Kuyken, W, MYRIAD Team. (2022). School-based mindfulness training in early adolescence: What works, for whom and how in the MYRIAD trial? Evidence-Based Mental Health, 25(3), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300439

- Montero-Marin, J., Taylor, L., Crane, C., Greenberg, M. T., Ford, T. J., Williams, J. M. G., García-Campayo, J., Sonley, A., Lord, L., Dalgleish, T., Blakemore, S.-J., & Kuyken, W, MYRIAD Team. (2021). Teachers "finding peace in a frantic world": An experimental study of self-taught and instructor-led mindfulness program formats on acceptability, effectiveness, and mechanisms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(8), 1689–1708. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000542

- Natividad, A., Huxley, E., Townsend, M. L., Grenyer, B. F. S., & Pickard, J. A. (2023). What aspects of mindfulness and emotion regulation underpin self-harm in individuals with borderline personality disorder? Journal of Mental Health, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2023.2182425

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M. J. D., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., … UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t; Review]. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31612-x

- Rose, G. (2008). Strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1992).

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Shinde, S., Weiss, H. A., Khandeparkar, P., Pereira, B., Sharma, A., Gupta, R., Ross, D. A., Patton, G., & Patel, V. (2020). A multicomponent secondary school health promotion intervention and adolescent health: An extension of the SEHER cluster randomised controlled trial in Bihar, India. PLOS Medicine, 17(2), e1003021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003021

- Stallard, P., Phillips, R., Montgomery, A. A., Spears, M., Anderson, R., Taylor, J., … Sayal, K. (2013). A cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of classroom-based cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in high-risk adolescents [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Health Technology Assessment, 17(47), 1–109. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta17470

- Tudor, K., Maloney, S., Raja, A., Baer, R., Blakemore, S.-J., Byford, S., Crane, C., Dalgleish, T., De Wilde, K., Ford, T., Greenberg, M., Hinze, V., Lord, L., Radley, L., Opaleye, E. S., Taylor, L., Ukoumunne, O. C., Viner, R., Kuyken, W., & Montero-Marin, J, MYRIAD Team. (2022). Universal mindfulness training in schools for adolescents: A scoping review and conceptual model of moderators, mediators, and implementation factors. Prevention Science, 23(6), 934–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01361-9

- World Health Organisation. (2022, 17 June). Mental health: Strengthening our response. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

- Yeager, D. S., Dahl, R. E., & Dweck, C. S. (2018). Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617722620