?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Averting incidents of patient self-harm is an ongoing challenge in acute inpatient mental health settings. Novel technologies that do not require continuous human visual monitoring and that maintain patient privacy may support staff in managing patient safety and intervening proactively to prevent self-harm incidents.

Aim

To assess the effect of implementing a contact-free vision-based patient monitoring and management (VBPMM) system on the rate of bedroom self-harm incidents.

Methods

A mixed methods non-randomized controlled before-and-after evaluation was conducted over 24 months on one female and one male acute inpatient mental health ward with the VBPMM system. The rates of bedroom self-harm, and of bedroom ligatures specifically, before and after implementation were investigated using quantitative methods. Qualitative methods were also used to explore the perceived effectiveness of the system and its acceptability.

Results

A −44% relative percentage change in bedroom self-harm incidents and a −48% relative percentage change in bedroom ligatures incidents were observed in the observational wards with the VBPMM system. Staff and patient responses gave insights into system acceptability and the ways in which these reductions may have been achieved.

Conclusion

The results indicate that using the VBPMM system helped staff to reduce self-harm incidents, including ligatures, in bedrooms.

Introduction

Incidents of self-harm are common in inpatient mental health settings, often preceded by complex behaviors that require deeper clinical understanding (Barnicot et al., Citation2017). These behaviors are thought to be motivated by emotional and psychiatric distress leading patients to inflict harm upon themselves, sometimes quite severe in nature (Klonsky et al., Citation2014). Patients at risk of self-harm are often cared for in acute care facilities under close supervision, which may create a feeling of restriction on the patient’s freedom and privacy (Barrera et al., Citation2020). Most episodes of self-harm are known to occur in private areas, including bedrooms and bathrooms (James et al., Citation2012).

The use of ligatures is a common method of self-harm, and it is reported that approximately three-quarters of patients who die by suicide on psychiatric wards do so using ligatures to cause strangulation (Hunt et al., Citation2012). In standard practice, patients are risk assessed and assigned an observation level such that they are checked on by staff periodically (typically every hour or every 15 min) or continuously observed if they are considered to be at high risk of self-harm. A patient on periodic checks may therefore be left unobserved by staff for up to an hour. Continuous in-person observation of patients is labor-intensive. Despite staff following policies and protocols for observations and other care practices, self-harm incidents still occur. A study exploring mental health nurses’ experiences of recognizing suicidal behavior, and dealing with the emotional challenges in the care of potentially suicidal inpatients, emphasizes the essential role nurses play in this context, along with the formal training needs required to be effective in critical situations (Hagen et al., Citation2017). Providing staff with additional information on when a patient may be at risk of self-harm could support them in reducing self-harm incidents.

VBPMM systems are assistive tools designed to support staff caring for patients in inpatient settings by enabling non-contact physiological and physical monitoring (Lloyd-Jukes et al., Citation2021).

A VBPMM system such as the one used in this study (Oxevision, Oxehealth Limited, Oxford UK) may be able to support staff to monitor patients at risk of self-harming through less intrusive means. The hardware of this VBPMM, including infrared illuminators and an infrared-sensitive camera, is mounted to the wall of ward bedrooms in a secure housing unit. The system is designed to support staff in mitigating the risk or preventing self-harm by providing:

Real-time alerts when a patient is detected to have entered the ensuite bathroom and not reappeared in the main bedroom area for a prolonged period of time, as self-harm may occur in the bathroom during this time;

An alert when a patient is detected to have been in a doorway for a prolonged period of time, where ligature points may exist;

A warning when multiple people are detected in a bedroom since it is possible that patients may incite each other to self-harm or provide the tools to do so;

Contact-free measurement of pulse rate and breathing rate, incorporating a remote visual check of the patient without disturbance (a 15-second video feed), to assess patient activity and identify potential self-harm risks or early warning signs;

Indication of whether a patient behavior is changing, such as when they are spending additional time in their bedroom and therefore may need engagement to avoid escalated risks.

Information from the system is made available to clinicians through portable tablets and a screen in the nurses’ station. There is no video feed continuously displayed with the VBPMM system: video can only be viewed for up to 15 s when taking vital sign measurements or when responding to an alert. In the latter instance, only deidentified blurred video is available.

Wright and Singh (Citation2022) evaluated the use of the VBPMM system to reduce bedroom falls in a dementia inpatient hospital. Their results showed a significant 48% reduction in the number of bedroom falls at night. Barrera et al. (Citation2020) evaluated the use of the VBPMM system to reduce disturbance to patients caused by periodic night-time observations, by performing some observations remotely rather than visiting patients’ rooms and opening doors or hatches. Their results indicated no adverse events or detriment to safety and a positive impact on patient and staff experiences at night. Although the work of Wright and Singh (Citation2022), Barrera et al. (Citation2020) and others (Clark et al., Citation2022) has examined the impact of using this technology in practice, this is the first opportunity to study its effects in supporting staff to the manage the risk or prevent self-harm in acute wards.

This evaluation, which took a similar approach to Wright et al. but in different settings, aimed to examine the effect of adopting the VBPMM system into existing clinical practice on the number of incidents of self-harm in bedrooms (all types and ligatures specifically) on acute mental health inpatient wards. A minor aspect of the study was to include patient and staff feedback.

Method

Study design

This was a mixed methods non-randomized controlled before-and-after evaluation within a pilot study approved by the Wales REC 5 Research Ethics Committee (reference 17/WA/0193) to assess the effects of implementing a contact-free VBPMM system in acute inpatient mental health wards. The introduction of the VBPMM system had been agreed by senior Trust managers, and the study team (led by K.W. as Chief Investigator and F.N. as Principal Investigator) was then formed to design and execute this study.

At Caludon Centre, Coventry & Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust (CWPT), two acute wards (22-bed female and 20-bed male) were fitted with the system (herein known as the observational wards). Control acute wards (20-bed male and 20-bed female) were selected based on the similarity of the patient cohort, ward size and clinical ways of working. The study was designed so that existing clinical protocols and practice would be followed throughout, and the technology would be used alongside, rather than replacing, existing aspects of care.

Study Participants

Participants consisted of staff working on acute wards and adult patients admitted to these wards. Upon admission to the observational wards, patients were provided with information about the system in an information leaflet and verbally through discussion with staff. Consent was sought from each patient for the use of the system in their room. If a patient lacked the capacity to decide whether to take part in the study, a suitable consultee could be sought (the patient’s carer or the ward’s Consultant Psychiatrist) to decide whether the patient would wish to participate if they had capacity. In this case, once the patient did have the capacity to consent, the patient was reengaged to establish whether they wished to participate. Where consent was not given, the system remained switched off in the patient’s bedroom for the duration of their stay. The consent rates for the observational wards were 67% for the female acute ward and 76% for the male acute ward.

The average age and broad categories of diagnosis were collected for the observational and control wards.

Measures

Self-harm rates

Rates of bedroom self-harm and ligatures were analyzed for both the observational and the control wards, before (“baseline period”) and after (“active period”) the VBPMM system went live on the observational wards. The number of ligature incidents was calculated as a subset of the total incidents of self-harm. Confounder analysis was conducted via interviews with Ward Managers to determine whether the results could have been influenced by variables other than the VBPMM system.

Patient perspectives

Patient questionnaires assessed their perceptions on the impact of having the system in their bedrooms covering disturbance, safety, care, privacy, and sleep. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

Staff perspectives

Staff questionnaires assessed the impact on clinical practice, patient safety, peace of mind in managing risk, patient care quality, and ease of use. Items were rated on a six-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree).

Staff semi-structured interviews were used to explore its potential role in supporting staff to manage risks and avert self-harm. The number and duration of interviews performed was limited by practicality of staff time and avoiding disruption to the wards. Therefore, rather than do a formal qualitative analysis, the interviews were reviewed for insights to better understand the role of the system in supporting staff to the manage the risk or prevent self-harm.

Data collection

Numbers of self-harm and ligature events were collected from the Trust incident reporting system, Datix. For the purpose of this study, any incident in the incident reporting system classified as “Self-harm” and its location specified as in the “Bedroom” or the “Bathroom” was included. Baseline data were collected for all wards when the system was not installed in the rooms, from 1st January 2018 – 31st December 2018. Data were compared with the active period from 1st January 2019 – 31st December 2019, when the system was installed and in use on the observational wards.

Staff interviews (n = 6) and questionnaires (n = 15) were conducted in April 2019. Questionnaires from patients (n = 12) were conducted in April 2019. Further interviews were conducted with staff (n = 6) in June 2020. The numbers of interviews and questionnaires conducted were guided by the availability of ward staff and the time burden on patients and staff.

Statistical analysis

The ward percentage change in incidents rates between the baseline and active period was calculated for the observational wards and the control wards. Where A1 and A0 refer to the incident rate for a given ward(s) (number of incidents/monthly occupancy rate) per 1000 occupied bed days in active and baseline periods respectively.

(1)

(1)

A relative percentage change in incident rates was calculated between the ward percentage change for the observational wards and control wards. Where A and C refer to observational and control wards respectively.

(2)

(2)

Incident data were normalized for ward monthly occupancy, which remained stable throughout the study period. Statistical significance was evaluated using the basic bootstrap method (also known as “Reverse Percentile Interval”) (Davison & Hinkley, Citation1997, p. 194 Equation (5.6)) with resampling applied over patients. This approach ensures that p-values account for variations in inter-patient event rates, unlike p-values generated via Chi-squared tests or bootstrapping over incidents. Incident rates were calculated to assess change in self-harm incidents (all types), and the number of ligature incidents across the two groups.

Results

The ages and diagnoses of patients were similar in the observational and control wards ().

Table 1. Study participant age and diagnoses.

Self-harm incidents

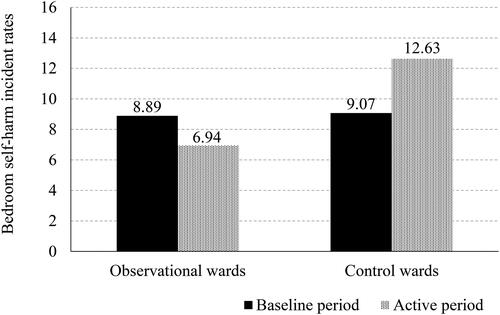

There was a relative percentage change of −44% (p < .002, 95% CI to [−100%, −14%]) in the number of self-harm incidents in the bedroom, which includes ensuite bathrooms, in the active period on the observational wards compared to the control wards. This result is obtained by using EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) ; (((6.94/8.89)/(12.63/9.07)) − 1) * 100.

Although it did not reach statistical significance, there was a −22% (p = .32, 95% CI [−100, +19%]) ward percentage change in incidents of self-harm in bedrooms, in the active period compared to the baseline period on the observational wards. This result is obtained by using EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) ; ((6.94/8.89) − 1) * 100. shows the rate of self-harm incidents in bedrooms across the wards during the study period.

Figure 1. Bedroom self-harm incident rates. This figure shows the rate of bedroom self-harm incidents per 1000 occupied bed days in the observational wards and control wards in the baseline period and active period.

Some of the open-ended feedback in the interviews gave insights into how the system was used to reduce self-harm. For example, one Ward Manager stated:

There has been a handful of incidents where someone has been in the bathroom for a length of time, and it has alerted us to that in between observational checks. Based on staff knowledge of the patient and using the system and intuition, we’ve been able to intercept things earlier than we might have done had we waited for the usual 15-minute check.

Ligature incidents

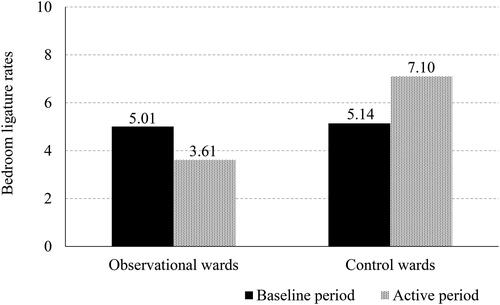

There was a −48% (p < .001, 95% CI [–100%, −16%]) relative percentage change of incidents of ligatures in the bedroom in the active period on the observational wards compared to the control wards. This result is obtained by using EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) ; (((3.61/5.01)/(7.10/5.14)) − 1) * 100. Further analysis of ligature incidents by location reveals a −68% (p < .001, 95%CI [−100%, −40%]) relative percentage change in ensuite bathroom ligatures in the active period across the observational wards. This result is obtained by using EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) ; (((0.48/1.41)/(1.86/1.77)) − 1) * 100. shows the rate of bedroom ligatures inclusive of bedrooms and ensuites. Some of the open-ended feedback in the interviews gave insights into how the system was used to reduce ligatures. For example, one Nurse stated:

Figure 2. Bedroom ligature incident rates. This figure shows the rate of bedroom ligature incidents per 1000 occupied bed days in the observational wards and control wards in the baseline period and active period.

We were concerned about a patient that was known to be at high risk of ligating. We had just done her observations, but we felt uneasy about her safety. In the past when we have concerns and go to their room, patients hear our footsteps and hide what they’re doing. In this case, we used the system to take a spot-check vital sign measurement and ensure she was ok in her bedroom. When doing so we could see that she was trying to tie something. We went to her room and removed the item before she could come to any harm.

A Healthcare Assistant stated:

There was an incident where a patient ligated. It alerted us [when she had spent 5 min in the ensuite bathroom]. This patient was quite a high risk, so we knew it would be important to know when she had gone into her bathroom for a long period.

Patient opinions

Almost all patients responding to the questionnaire reported feeling reassured about their safety with the system in place (11 out of 12), the one remaining patient was unsure. Most patients felt reassured that their physical health is being looked after with the system in place (10 out of 12), the two remaining patients were unsure. The majority of patients responding felt the system could improve their well-being (8 out of 12), the remaining four patients were unsure. Responses indicate that patients are not disturbed by the equipment in their room (9 out of 12) with one disagreeing and two unsure. Patients also indicated the equipment does not disturb their sleep (8 out of 12), with two disagreeing and two unsure. Half of the patients responding indicated that the system could improve their privacy (6 out of 12), with four disagreeing and two patients unsure.

Staff opinions

All respondents (n = 15) indicated that the system had enabled staff to identify incidents which they would otherwise not have known about and that the vital sign measurement tool reassures them about patient safety.

Nearly all staff (14 out of 15) reported that the system helped them to provide better care for patients, that the system provides more information for clinical decisions and they have greater peace of mind in managing patient risk, with the remaining one staff member disagreeing.

A majority of respondents indicated that the system slots well into their existing care routines (12 out of 15) and almost all respondents found the system easy to use (13 out of 14), with the remaining staff disagreeing.

Discussion

These results indicate that the wards using the VBPMM system experienced a reduction in the numbers of bedroom self-harm incidents (all types) and ligature incidents specifically, relative to control wards without the system. This study was not designed to map staff using functionality to the changes in self-harm rates. However, it is possible by looking at the qualitative feedback to gain some insight into the mechanisms by which staff use the system to avert these incidents and methods by which they felt that the use of the VBPMM system had improved patient safety on the wards.

The system alerts staff if it detects a patient is spending prolonged time in the ensuite bathroom or by a doorway, which are higher-risk areas for self-harm. This creates an opportunity for staff to intervene if appropriate, using their knowledge of the patient and the patient’s risk of self-harm.

Staff can use the system to measure vital signs remotely without disturbing the patient. This measurement process includes a 15-second visual feed which allows a visual check of patient activity/behavior. Staff reported that this can help to intervene on self-harm that may have otherwise not been known about. Future work can explore the ways in which staff use the VBPMM system to manage risk and avert self-harm incidents.

This paper is concerned with incidents of self-harm and incidents of ligature, but the responses from staff and patients questionnaires suggest that the system was seen as supportive in other respects. These include providing an option to supporting physical health checks and providing more information for clinical decisions. Additional research on using the system in inpatient mental health settings could explore patient and staff perspectives in greater depth.

Ethical and privacy aspects are important considerations when implementing a vision-based technology. For this VBPMM system, there is no video feed continuously displayed; identifiable video can only be viewed by staff, for up to 15 s, when taking vital sign measurements. When responding to an alert, only deidentified, heavily blurred video is available. Patients were informed about the use of the system upon admission verbally and with written information and had to consent for it to be switched on. National guidance on implementing VBPMM systems including service user and carer engagement, information and communication has been developed by the National Mental Health and Learning Disability Nurse Directors Forum to support the introduction of VBPMM systems on mental health inpatient wards effectively and ethically.

Limitations

A limitation of this analysis is the inclusion of wards from a single hospital. Bowers et al. (Citation2008) reported multiple sources of variability when comparing incident rates across acute psychiatric wards from a single hospital and across several NHS Trusts. In the work reported here, possible confounding effects were examined through discussions with ward managers, but remain a potential limitation of this type of analysis. Patients in the study reported here were not randomized to control or intervention groups within the same ward, as it was anticipated that this would place an undue burden on staff. A future study could perhaps evaluate the particular role of the system in individual incidents, or near-misses, to assess more precisely the impact of different functionality of the system.

A potential bias in this study might be caused by the awareness of staff and patients of the introduction of a novel technology. However, the study duration was long enough to reduce transient effects related to the introduction of new technology, and the technology itself is unobtrusive and does not require substantial changes to ways of working.

This study provided a limited understanding on staff and patient perspectives and the mechanism of change in which the VBPMM system is adopted into ward staffs’ clinical workflows. Specifically, the mechanisms by which particular functionality of the VBPMM is used by staff to identify or avert particular types of self-harm incident cannot be examined in detail in a study of this type. Further work should include a detailed analysis of these mechanisms of change so that the links between individual incidents and overall changes in rates of self-harm can be examined. Future research can also establish in more detail the perceptions of staff and patients of VBPMM systems.

Conclusion

Reductions in bedroom self-harm incident rates and bedroom ligature incident rates specifically were observed in wards using the system compared to control wards. Staff interviews and questionnaires give some indication how the system may have supported staff in averting incidents, in particular self-harm. Feedback from staff and patients indicated that using a VBPMM system on the wards was well accepted.

Disclosure statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors time was funded by their respective employers (CWPT for authors 1 and 2, Oxehealth Limited for authors 3 and 4). In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and the ethical obligation as researchers, it is being disclosed that authors 3 and 4 have a financial interests in the supplier of the technology used in this study. These interests are disclosed fully to Taylor & Francis, and an approved plan is in place for managing any potential conflicts arising from that involvement.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnicot, K., Insua-Summerhayes, B., Plummer, E., Hart, A., Barker, C., & Priebe, S. (2017). Staff and patient experiences of decision-making about continuous observation in psychiatric hospitals. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(4), 473–483. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1338-4.

- Barrera, A., Gee, C., Wood, A., Gibson, O., Bayley, D., & Geddes, J. (2020). Introducing artificial intelligence in acute psychiatric inpatient care: Qualitative study of its use to conduct nursing observations. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 23(1), 34–38. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300136.

- Bowers, L., Whittington, R., Nolan, P., Parkin, D., Curtis, S., Bhui, K., Hackney, D., Allan, T., & Simpson, A. (2008). Relationship between service ecology, special observation and self-harm during acute in-patient care: City-128 study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(5), 395–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037721.

- Clark, H., Edwards, A., Davies, R., Bolade, A., Leaton, R., Rathouse, R., Easterling, M., Adeduro, R., Green, M., Kapfunde, W., Olawoyin, O., Vallianatou, K., Bayley, D., Gibson, O., Wood, C., & Sethi, F. (2022). Non-contact physical health monitoring in mental health seclusion. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 18(1), 31–37. doi: 10.20299/jpi.2021.009.

- Davison, A. C., & Hinkley, D. v (1997). Bootstrap Methods and their Application. In Bootstrap Methods and their Application. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511802843.

- Hagen, J., Knizek, B. L., & Hjelmeland, H. (2017). Mental health nurses’ experiences of caring for suicidal patients in psychiatric wards: An emotional endeavor. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(1), 31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.018.

- Hunt, I. M., Windfuhr, K., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2012). Ligature points and ligature types used by psychiatric inpatients who die by hanging a national study. Crisis, 33(2), 87–94. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000117.

- James, K., Stewart, D., Wright, S., & Bowers, L. (2012). Self harm in adult inpatient psychiatric care: A national study of incident reports in the UK. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(10), 1212–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.010.

- Klonsky, E., Victor, S., & Saffer, B. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury: What we know, and what we need to know. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(11), 565–568. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901101.

- Lloyd-Jukes, H., Gibson, O. J., Wrench, T., Odunlade, A., & Tarassenko, L. (2021). Vision-based patient monitoring and management in mental health settings. Journal of Clinical Engineering, 46(1), 36–43. doi: 10.1097/JCE.0000000000000447.

- Wright, K., & Singh, S. (2022). Reducing falls in dementia inpatients using vision-based technology. Journal of Patient Safety, 18(3), 177–181. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000882.