Abstract

Background

Common mental health problems (CMHP) are prevalent among junior doctors and medical students, and the COVID-19 pandemic has brought challenging situations with education disruptions, early graduations, and front-line work. CMHPs can have detrimental consequences on clinical safety and healthcare colleagues; thus, it is vital to assess the overall prevalence and available interventions to provide institutional-level support.

Aims

This overview summarises the prevalence of CMHPs from existing published systematic reviews and informs public health prevention and early intervention practice.

Methods

Four electronic databases were searched from 2012 to identify systematic reviews on the prevalence of CMHPs and/or interventions to tackle them.

Results

Thirty-six reviews were included: 25 assessing prevalence and 11 assessing interventions. Across systematic reviews, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 7.04 to 88.30%, burnout from 7.0 to 86.0%, depression from 11.0 to 66.5%, stress from 29.6 to 49.9%, suicidal ideation from 3.0 to 53.9% and one obsessive-compulsive disorder review reported a prevalence of 3.8%. Mindfulness-based interventions were included in all reviews, with mixed findings for each CMHP.

Conclusions

The prevalence of CMHPs is high among junior doctors and medical students, with anxiety remaining relatively stable and depression slightly increasing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research on mindfulness-based interventions is required for a resilient and healthy future workforce.

PRISMA/PROSPERO

the researchers have followed PRISMA guidance. This overview was not registered with PROSPERO as it was conducted as part of an MSc research project.

Introduction

Medical careers are renowned for their demanding nature and challenging environments (Sekhar et al., Citation2021). Due to laborious working conditions and exposure to occupational hazards (e.g. occupational infections and radiation exposure) (Naithani et al., Citation2021), all healthcare professionals are susceptible to illness (Søvold et al., Citation2021). Mental difficulties are a growing public health concern (Jacob et al., Citation2020), and evidence suggests that the prevalence may be higher among healthcare professionals (Weibelzahl et al., Citation2021). Junior doctors and medical students are recognised for experiencing stressors during their rigorous training programmes; and, consequently, increased strain on their mental health (Sekhar et al., Citation2021). This risk is further compounded by lengthy work/study times and an increased financial burden (Tam et al., Citation2019), along with an increased likelihood of possessing personality characteristics like maladaptive perfectionism (Prabhu & Rashad, Citation2021).

Common mental health problems are characterised by changes to behaviour and emotional control; they are typically linked to functional impairment, and the most prevalent are anxiety disorders, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (NICE, Citation2022a). Common mental health problems can have detrimental effects on working ability and performance (Khan et al., Citation2006). A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of depression in medical students to be 27.2% and 11.1% for suicidal ideation (Rotenstein et al., Citation2016). A further systematic review found a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic than that of the general population (37.9% and 33.7% vs 24.2% and 21.3%) (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2021; Jia et al., Citation2022). According to the NHS sickness absence rates from January 2022, anxiety/stress/depression/other psychiatric illnesses are the most frequently represented sickness absence reasons among all NHS workers (19.9%) (Statistics – NHS Digital, Citation2022), which, correspondingly, increases the pressure on healthcare services and affects patient care. This reinforces the significance of assessing the prevalence and available interventions during medical training to inform efforts to prevent and treat causes of mental distress and ensure that there is institutional-level support for their mental health, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

There have been previous attempts to summarise the body of evidence from published systematic reviews on the prevalence of common mental health problems and interventions to tackle them, albeit with a discrete focus on individual common mental health problems. Overviews of systematic reviews have the benefit of summarising different prevalence rates and effects of interventions for the same disorder or target group where many systematic reviews are already available (Pollock et al., Citation2022). Given the plethora of existing systematic reviews, it was decided to conduct an overview of systematic reviews to gather and assess the evidence on the prevalence of common mental health problems and interventions to inform clinical practice, understand their consequences and avoid the need for additional systematic reviews.

Appendix 1 Provides definitions of the abbreviations.

Aim and objectives

The overall aim is to summarise the prevalence of common mental health problems and interventions for junior doctors and medical students from existing published systematic reviews; this information can then be used to inform public health prevention and early intervention practice.

The objectives are:

To collate the overall prevalence of common mental health problems in junior doctors and medical students.

To highlight the change in prevalence rates during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To assess the evidence on the effects of interventions to tackle common mental health problems.

Methods

Study design and research protocol

This overview was conducted in adherence with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., Citation2019) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis-(PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were divided into two parts, and all published systematic reviews met the following inclusion criteria.

Prevalence of common mental health problem(s):

Study designs: a systematic review and/or meta-analysis

Participants: Junior Doctors and/or Medical Students

Common mental health problems:

Common mental health problems are characterised by clinically significant impairment to behaviour, emotional control, and individual intellect; it is typically linked to functional impairment and the most prevalent and included in the inclusion criteria are anxiety disorders, stress, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, burnout, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE, Citation2022a).

Outcome measure: Prevalence of common mental health problem(s)

Interventions to tackle common mental health problem(s):

Study designs: a systematic review and/or meta-analysis

Participants: Junior Doctors and/or Medical Students

Common mental health problem: as defined above

Outcome measure: Improvement in common mental health problem(s)

Intervention: Any social or psychological intervention(s)

Comparator: Any comparator investigated

Literature search

A search of major electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, ERIC, PsycINFO) was conducted on 16 May 2022 to identify eligible systematic reviews published in the English language from 2012, allowing for ten years’ worth of data to be collected that is most relevant to today’s junior doctors and medical students.

The search strategies were designed to include an appropriate combination of MeSH and text words for the population of interest (e.g. medical students, student doctors, student physicians), types of common mental health problems (e.g. depression, anxiety, burnout, stress) and interventions to tackle them (e.g. counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness). Different facets of the search were combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” when appropriate. An example of the search strategies is included in Appendix 2. Additionally, the citation lists of identified systematic reviews were perused to identify further eligible reviews.

Data extraction and quality assessment of included reviews

Citations’ titles and abstracts were reviewed by the primary author (SA), who then retrieved potentially relevant articles for full-text screening; any uncertainty or doubt about eligibility was discussed among all review authors to ensure that no potentially relevant papers were discarded. The full-text assessment was conducted according to the pre-specified inclusion criteria. Data extraction was performed by the primary review author (SA); however, 20% of the included reviews were randomly checked by co-authors, three experts of this overview. Details recorded for systematic reviews assessing the prevalence of common mental health problems included: publication dates and the scope of the review, target population and the number of participants, and included studies, type of common mental health problem, and review outcomes. For systematic reviews assessing interventions to tackle common mental health problems in addition to the review characteristics, information on the characteristics of interventions, comparators and outcome measures were recorded. Appendix 3 provides the data extraction forms. Measures of effect and accompanied confidence intervals (CI) were noted for systematic reviews with a meta-analysis component.

The quality of the eligible systematic reviews was assessed using the validated AMSTAR-2 tool (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews-2), consisting of 16 items (Shea et al., Citation2017), where each review received an overall quality rating. Reviews were not excluded based on AMSTAR-2 ratings.

Data synthesis

The main characteristics of each identified review and the relevant outcomes (prevalence rates and the effects of interventions) were summarised using summary tables with no attempt to standardise results across reviews.

Results

Literature search

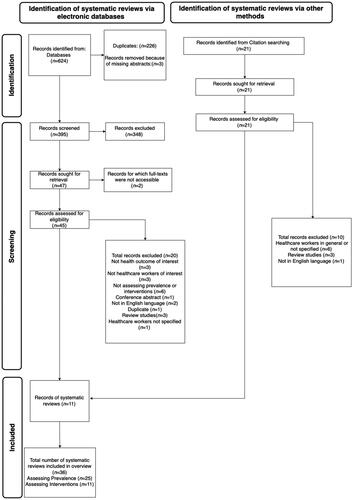

The literature searches retrieved 624 records. After eliminating duplicates, 395 citations were screened for eligibility, and 47 citations were selected for full-text screening, of which 45 were accessible. Twenty reviews were subsequently excluded as they failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Eleven reviews were identified by citation searching, and ultimately, 36 systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) were deemed suitable for inclusion.

The PRISMA diagram in summarises the study selection process.

Study details

Twenty-five reviews were on the prevalence of common mental health problems (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015; Chunming et al., Citation2017; Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Erschens et al., Citation2019; Frajerman et al., Citation2019; Galaiya et al., Citation2020; Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; IsHak et al., Citation2013; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Lawlor et al., Citation2022; Lei et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2021; Low et al., Citation2019; Mao et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Quek et al., Citation2019; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Santabárbara et al., Citation2021; Shah et al., Citation2023; Zeng et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2020) and 11 assessed the effects of common mental health problem interventions (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Regehr et al., Citation2014; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Shiralkar et al., Citation2013; Walsh et al., Citation2019; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021).

Across the 25 reviews assessing prevalence, the number of included studies ranged between 3-and 62 and the participants from 979-to 69,423. Twelve reviews focused on burnout (Chunming et al., Citation2017; Erschens et al., Citation2019; Frajerman et al., Citation2019; Galaiya et al., Citation2020; IsHak et al., Citation2013; Lawlor et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2021; Low et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2023; Zhou et al., Citation2020), 12 on depression (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Lei et al., Citation2016; Mao et al., Citation2019; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Santabárbara et al., Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2019), eight on anxiety (Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Mao et al., Citation2019; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Quek et al., Citation2019; Zeng et al., Citation2019), five on suicidal ideation (Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Zeng et al., Citation2019), three on stress/psychological distress (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Zhou et al., Citation2020) and one on-obsessive-compulsive disorder (Pacheco et al., Citation2017). Eleven used validated outcome measuring tools (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015; Chunming et al., Citation2017; Erschens et al., Citation2019; Frajerman et al., Citation2019; IsHak et al., Citation2013; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Lawlor et al., Citation2022; Low et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Santabárbara et al., Citation2021) and 14 used a mixture of validated and non-validated methods (Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Galaiya et al., Citation2020; Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lei et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2021; Mao et al., Citation2019; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Quek et al., Citation2019; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Shah et al., Citation2023; Zeng et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2020) (see Appendix 4).

Across the 11 reviews assessing interventions, the number of included studies ranged between 2 to 39 and the number of participants from 99 to 7,387. Ten reviews focused on stress (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Regehr et al., Citation2014; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Shiralkar et al., Citation2013; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021), seven on burnout (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Regehr et al., Citation2014; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Walsh et al., Citation2019; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021), six on depression (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Witt et al., Citation2019), five on anxiety (Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Witt et al., Citation2019) and one on suicidal ideation (Witt et al., Citation2019). All reviews included elements of mindfulness-based practices, assessing the effects of different forms of mindfulness-based interventions. Four reviews included papers with only validated outcome measuring tools (Regehr et al., Citation2014; Shiralkar et al., Citation2013; Walsh et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021), and seven reviews included papers with a mixture of validated and non-validated methods (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Witt et al., Citation2019) (see Appendix 5).

All reviews included both male and female participants. Reviews that reported information on the gender of participants were predominantly female.

The basic characteristics of the 36 included systematic reviews assessing prevalence are shown in , and the systematic reviews assessing interventions in .

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the systematic reviews and meta-analysis included in the overview – prevalence.

Table 2. Basic characteristics of systematic reviews and meta-analysis included in the overview – interventions.

Methodological quality of included systematic reviews

Among the reviews assessing prevalence, there were 13 of high quality (Frajerman et al., Citation2019; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Lei et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2021; Low et al., Citation2019; Mao et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Quek et al., Citation2019; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Santabárbara et al., Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2020), one of moderate quality (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014), one of low quality (Pacheco et al., Citation2017), and ten of critically low quality (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015; Chunming et al., Citation2017; Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Erschens et al., Citation2019; Galaiya et al., Citation2020; IsHak et al., Citation2013; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lawlor et al., Citation2022; Shah et al., Citation2023) (Appendix 6).

Regarding the reviews assessing interventions, there were three of high quality (Kunzler et al., Citation2020; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Witt et al., Citation2019), seven of moderate quality (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; McConville et al., Citation2017; Regehr et al., Citation2014; Walsh et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021), and one of critically low quality (Shiralkar et al., Citation2013) (Appendix 7).

Synthesis of results

Prevalence

shows the prevalence rates of common mental health problems among junior doctors and medical students as reported by the identified systematic reviews, and Appendix 8 provides definitions of the included common mental health problems.

Table 3. Summary of results on the prevalence of common mental health problems across systematic reviews.

(a) Anxiety

Of the eight reviews focusing on anxiety in medical students, the pooled prevalence rates in the six meta-analyses were between 7.04-to 33.8% (Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Quek et al., Citation2019; Zeng et al., Citation2019) and between 7.7-to 88.3% in the two reviews that reported only ranges (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Mao et al., Citation2019). The reasons for reporting ranges varied from using different assessment tools (Mao et al., Citation2019) to not stating cut-off scores and not examining anxiety in a formal way (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014). Of the meta-analyses that provided a pooled prevalence rate, the highest anxiety prevalence rate was 33.8% and was conducted globally (Quek et al., Citation2019); however, when anxiety prevalence rates were grouped by continent, the prevalence was highest in the Middle East at 42.4%, followed by Asia at 35.2% (Quek et al., Citation2019). This is similar to the prevalence rate reported in another review that focused on anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (33.7%) (Jia et al., Citation2022). Two reviews found anxiety prevalence rates since the COVID-19 pandemic to be relatively stable 28.0% (Lasheras et al., Citation2020)-and 33.7% (Jia et al., Citation2022) compared to pre-COVID-19 pandemic 33.8% (Quek et al., Citation2019)-and 32.9% (Pacheco et al., Citation2017). Measuring instruments included the Beck-Anxiety-Inventory-(BAI) (Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Mao et al., Citation2019; Pacheco et al., Citation2017) and the Generalised-Anxiety-Disorder-Assessment-(GAD-7)-tools (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020).

(b) Burnout

Twelve reviews investigated burnout and of these, six focused on medical students (Chunming et al., Citation2017; Erschens et al., Citation2019; Frajerman et al., Citation2019; IsHak et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2021; Pacheco et al., Citation2017) and six on trainee doctors and surgeons (Galaiya et al., Citation2020; Lawlor et al., Citation2022; Low et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Shah et al., Citation2023; Zhou et al., Citation2020). Of the six reviews looking at medical students, four meta-analyses reported having a pooled prevalence rate of 13.1-to 45.9% (Chunming et al., Citation2017; Frajerman et al., Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2021; Pacheco et al., Citation2017). In the two reviews that reported only ranges, the prevalence rates were between 7.0-to 75.2% (Erschens et al., Citation2019; IsHak et al., Citation2013). The reasons for reporting ranges were using different measuring instruments (Erschens et al., Citation2019) and variable population characteristics such as life factors, learning environments and minority status (IsHak et al., Citation2013). The six remaining reviews considered trainee doctors and surgeons, and of these, three global reviews reported pooled prevalence rates from 43.1-to 51.0% (Low et al., Citation2019; Naji et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2020) and a US review reported a prevalence rate of 58.6% (Lawlor et al., Citation2022). Two reviews reported only ranges from 22.2-to 86.0% (Galaiya et al., Citation2020; Shah et al., Citation2023), ; citing differing definitions of burnout in one review (Galaiya et al., Citation2020) and the use of varying Maslach-Burnout-Inventory-(MBI) versions in another (Shah et al., Citation2023). All reviews used the MBI or its modified forms. To the authors’ knowledge, no reviews on burnout were conducted since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

(c) Depression

All 12 reviews focused on medical students, with two of these comparing medical students to non-medical students (Lei et al., Citation2016; Puthran et al., Citation2016). Of the ten reviews that solely focused on medical students, the pooled prevalence rates were 11.0-to 37.9% in eight reviews (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Jia et al., Citation2022; Lasheras et al., Citation2020; Pacheco et al., Citation2017; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Santabárbara et al., Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2019) and in the two reviews that reported only ranges, 6.0-to 76.1% (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014; Mao et al., Citation2019). Reasons for reporting ranges were variable qualities of included studies, using the same tool but different cut-off scores (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014) and utilising different assessment tools (Mao et al., Citation2019). For the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), >14/63 diagnosed depression in one Pakistani study (Alvi et al., Citation2010) and another Macedonian >17/63 (Mancevska et al., Citation2008), with many not reporting their cut-off scores (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014). Two reviews compared medical students to non-medical students; there was no clear increasing trend when comparing the prevalence rates of depression in medical students, 27.5% (Lei et al., Citation2016) vs 28.0% (Puthran et al., Citation2016), and non-medical students, 22.4% (Lei et al., Citation2016)-vs 30.6% (Puthran et al., Citation2016). Additionally, three reviews on medical students assessed the prevalence of depression since the COVID-19 pandemic, and, generally, showed slightly higher prevalence rates (25.0 (Lasheras et al., Citation2020), 31.0% (Santabárbara et al., Citation2021). 37.9% (Jia et al., Citation2022)) compared to pre-COVID-19 pandemic (15.1% (Bacchi & Licinio, Citation2015), −11.0%, (Cuttilan et al., Citation2016), 27.2% (Rotenstein et al., Citation2016)). Most reviews used the-BDI measuring tool.

(d) Obsessive-compulsive disorder

One review looked at the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in medical students and reported a prevalence rate of 3.8% (Pacheco et al., Citation2017), using the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised-(OCI-R) (Pacheco et al., Citation2017).

(e) Stress/psychological distress

Two reviews investigated the prevalence of stress (Pacheco et al., Citation2017) and psychological distress (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014) among medical students and one review looked at stress in trainee physicians (Zhou et al., Citation2020). Prevalence rates from the three reviews were 49.9% (Pacheco et al., Citation2017), 29.6% (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014)-and 44.6% (Zhou et al., Citation2020), respectively. The differences in prevalence rates can be explained by year of study as psychological distress is known to be more common as medical students progress through their course (Hope & Henderson, Citation2014). All reviews used the General-Health-Questionnaire-(GHQ)-instrument.

(f) Suicidal ideation/thoughts

Five reviews explored the prevalence of suicidal ideation in medical students and of these four reported pooled prevalence rates between 3.0%-to 11.1% (Cuttilan et al., Citation2016; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Zeng et al., Citation2019). One review reported a range between 1.8%-and 53.6% reflecting the heterogeneity amongst its studies (e.g. different evaluation timeframes and the use of various measuring tools) (Coentre & Góis, Citation2018). Measuring instruments included the BDI (Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Cuttilan et al., Citation2016) and the Patient-Health-Questionnaire-(PHQ) (Coentre & Góis, Citation2018; Puthran et al., Citation2016; Rotenstein et al., Citation2016; Zeng et al., Citation2019).

Interventions

Common mental health problems are frequently targeted by different forms of public mental health interventions. Given the abundance of available interventions, it is essential that effective interventions are identified and implemented (Das et al., Citation2016). provides details of the included reviews, which assessed the effects of interventions to tackle common mental health problems.

Table 4. Summary of the findings of systematic reviews assessing interventions to tackle common mental health problems.

The definitions of mindfulness-based interventions, mindfulness-based stress-reduction-(MBSR) and other interventions are detailed in Appendix 9.

(a) Anxiety

Five reviews focused on interventions to treat anxiety among healthcare students (two reviews) (Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017), newly qualified doctors-(one review) (Krishnan et al., Citation2022), medical students-(one review) (Witt et al., Citation2019) and junior doctors and medical students (one review) (Sekhar et al., Citation2021). Two reviews used MBSR in healthcare students and medical students (McConville et al., Citation2017; Witt et al., Citation2019). Results showed a significant effect favouring MBSR in reducing anxiety levels (SMD–0.44, −95% CI–0.59-to–0.28 (McConville et al., Citation2017)-and-SMD–0.62, −95%-CI–1.63-to 0.38 (Witt et al., Citation2019), respectively). Additionally, a review on newly qualified doctors found statistically significant results in reducing anxiety by using mental practice-(p < 0.05) and assistantship training-(p < 0.03) (Krishnan et al., Citation2022). A review on psychological interventions in healthcare students reported that resilience training lowered levels of anxiety post-intervention (SMD–0.45, −95%-CI–0.84-to 0.06) (Kunzler et al., Citation2020). Conversely, a review on mindfulness-based interventions in junior doctors and medical students showed no substantial improvement in anxiety immediately post-intervention (SMD 0.09, 95%-CI–0.33-to 0.52) (Sekhar et al., Citation2021).

(b) Burnout

Seven reviews investigated interventions for burnout with four focusing on medical students (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021) and three combining junior doctors and medical students (Regehr et al., Citation2014; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Walsh et al., Citation2019). One review on mindfulness-based interventions in medical students found a significant reduction in burnout favouring meditation, and mindfulness body scans-(p = 0.001) whereas physical/mental exercises were insignificant-(p = 0.204) (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018). Additionally, mindfulness-based interventions were reported to be effective in medical students and residents (SMD–0.38, 95%-CI −0.49-to–0.26) (Regehr et al., Citation2014). A review on MBSR (didactic teaching, physical/mental exercises) in junior doctors and medical students found that most interventions reported improvements, however, duty hour restrictions reported mixed findings (Walsh et al., Citation2019). A review of MBSR in medical students showed non-significant improvements post-intervention (SMD–0.13, 95%-CI–0.36-to 0.10) (Witt et al., Citation2019). Similarly, junior doctors and medical students using MBSR found no substantial difference post-intervention (SMD–0.42, 95%-CI–0.84-to 0.00) (Sekhar et al., Citation2021). Moreover, online mindfulness-based interventions in medical students showed no changes in the MBI-subscales of personal achievement-(p = 0.55), emotional exhaustion-(p = 0.51), and depersonalization-(p = 0.71) (Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021). Another review on mindfulness-based interventions in medical students reported inconclusive results (Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022).

(c) Depression

Five reviews explored interventions for depression (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Witt et al., Citation2019); one review highlighted that MBSR in healthcare students showed a significant effect favouring mindfulness-based interventions for depression (SMD–0.54, 95%-CI–0.83-to–0.26) (McConville et al., Citation2017). Similarly, two reviews on mindfulness-based interventions in medical students reported a significant reduction in depression (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018) and suggested that MBSR interventions may be effective in reducing depression levels (SMD–0.62, 95%-CI–1.63-to 0.38) (Witt et al., Citation2019). Contrarily, one review showed a small-to-no effect of resilience training on depression among healthcare students (SMD–0.20, 95%-CI–0.52-to 0.22) (Kunzler et al., Citation2020) and another review showed no difference in depression levels among junior doctors and medical students after mindfulness-based interventions (SMD 0.06, 95%-CI–0.19-to 0.31) (Sekhar et al., Citation2021).

(d) Stress/psychological distress

Ten reviews looked at stress/psychological distress with nine reporting positive findings (Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Krishnan et al., Citation2022; Kunzler et al., Citation2020; McConville et al., Citation2017; Regehr et al., Citation2014; Sekhar et al., Citation2021; Shiralkar et al., Citation2013; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021). Two reviews on mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare students found a significant effect favouring mindfulness-based interventions for stress (SMD–0.44, 95%-CI–0.57-to–0.31) (McConville et al., Citation2017) and resilience training with lower levels of stress (SMD–0.28, 95%-CI–0.48-to 0.09) (Kunzler et al., Citation2020). Similarly, four reviews on mindfulness-based interventions in medical students found it to be effective in reducing stress (Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022; Shiralkar et al., Citation2013; Witt et al., Citation2019; Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021) (SMD–0.66, 95%-CI–1.32-to–0.00) (Witt et al., Citation2019), showed significant change at follow-up on the perceived stress scale (p = 0.0005) (Yogeswaran & El Morr, Citation2021) and highlighted its effectiveness in reducing short-and-long-term stress among medical students (SMD 0.29, 95%-CI 0.07-to 0.51), and at 6-month follow-up (SMD 0.31, 95%-CI 0.06-to 0.55) (Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022). Another two reviews on junior doctors and medical students found MBSR techniques to have significant positive results on stress (SMD–0.55, 95%-CI–0.74-to–0.36 (Regehr et al., Citation2014)-and-SMD–0.36, 95%-CI–0.60-to 0.13 (Sekhar et al., Citation2021), respectively). A further review on newly qualified doctors found mindfulness courses and mental practice to decrease stress levels-(p = 0.04)-and-(p < 0.05) (Krishnan et al., Citation2022). Contrastingly, a review assessing MBSR to reduce stress among medical students reported mixed results (Daya & Hearn, Citation2018).

(e) Suicidal ideation/thoughts

One review found that interventions designed to prevent depression among medical students had unclear effects on suicidal ideation (OR 0.07, 95%-CI 0.05-to 1.36) (Witt et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

This overview aimed to investigate the worldwide prevalence of common mental health problems among junior doctors and medical students. Twenty-five published systematic reviews from 2012 with a pooled population of 531,556 medical students and 173,030 junior doctors were assessed. Across systematic reviews, the prevalence of anxiety ranged from 7.04 to 88.30%, burnout from 7.0 to 86.0%, depression from 11.0 to 66.5%, stress from 29.6 to 49.9%, suicidal ideation from 3.0 to 53.9% and one obsessive-compulsive disorder review reported a prevalence of 3.8%. Mindfulness-based interventions were the most used interventions, with mixed findings for each common mental health problem.

Findings show high prevalence rates of common mental health problems, with the peak age for onset occurring between adolescence and early adulthood (Jurewicz, Citation2015) owing to establishing independence, risk-taking behaviours and neurodevelopmental changes rendering it a vulnerable period for the development of common mental health problems (Colizzi et al., Citation2020). This, coupled with general university stresses, heavy workloads, challenging clinical environments, and career planning uncertainties, further increases the risk of common mental health problems (Card, Citation2018; Jafari et al., Citation2012).

Clear links between financial pressures over repaying debt whilst at medical school and the development of common mental health problems have been described (Dossey, Citation2007; Pisaniello et al., Citation2019), especially in rural students (Kwong et al., Citation2005). Medical students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds have reported higher risks of suicidal ideation (Seo et al., Citation2021).

The prevalence of anxiety, depression and stress is higher in junior doctors and medical students (32.9%, 30.6%, −49.9%) (Pacheco et al., Citation2017) compared to the general population (26.9%, 28.0%, and 36.5%) (Nochaiwong et al., Citation2021). The prevalence of depression among undergraduate university students was 25% (Sheldon et al., Citation2021), which is relatively similar to that of non-medical students reported in two of the included reviews (22.4%-and 28.7%) (Lei et al., Citation2016; Puthran et al., Citation2016). Heavier academic pressures, tense junior-senior relationships, high-intensity internships, and consequent sleep deprivation may explain this discrepancy. Common mental health problems can lead to undesirable consequences, including suicidal ideation, poor academic performance, and compromised patient safety (Zeng et al., Citation2019).

When understanding common mental health problems, it is vital to be aware of the wider social context and cultural aspects that may influence treatment-seeking behaviours (Doll et al., Citation2021). This overview found that when comparing the prevalence of anxiety in medical students across different continents, the Middle East and Asia had the highest prevalence of anxiety (Quek et al., Citation2019). Cultural differences across countries may explain this; in the Middle East, emotions are often concealed due to the associated stigma (Abdullah & Brown, Citation2011), and in Asia, common mental health problems are considered a shame to one’s family (Littlewood et al., Citation2007). In contrast, Caucasians may experience less stigmatisation than other sociocultural groups (Rao et al., Citation2007). Therefore, it is important to consider these unique socio-cultural contexts when dealing with common mental health problems, which can be considered when treating and designing public health interventions.

The COVID-19 pandemic is thought to have increased the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the general population (Sousa et al., Citation2021), with medical students particularly reported to have higher prevalence rates (33.7% (Jia et al., Citation2022)-and 37.9% (Jia et al., Citation2022)) than the general population-(27.7%-and 26.9) (Sousa et al., Citation2021). Reasons for this could include the change to inherent training models of medical schools, limited clinical experience, and online learning (Jia et al., Citation2022; Natalia & Syakurah, Citation2021).

This overview highlighted that the most common forms of public mental health interventions for common mental health problems are mindfulness-based interventions and MBSR. Results show that mindfulness-based interventions significantly reduced stress, which is consistent across reviews despite the interventions being undertaken in different countries with varying lengths and components (e.g. meditation, cognitive restructuring) (Hathaisaard et al., Citation2022). These results are comparable to those of an earlier review that assessed interventions to reduce burnout in doctors (SMD 0.38, 95%-CI 0.26-to–0.46) (Regehr et al., Citation2014). Other approaches, namely mental practice and assistantship training, have also reported promising findings (Krishnan et al., Citation2022).

It is evident from the included reviews that there is a lack of consensus on the definitions of common mental health problems. For example, “burnout” has been defined differently over time with several validated measuring tools being used. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory highlights fatigue and exhaustion as the main characteristics of the problem (Kristensen et al., Citation2005), whilst other tools describe it as a depressive disorder (Bianchi et al., Citation2014). Even when using the MBI, there is no consensus on the definition of burnout, which limits the interpretation and generalisability of findings (Galaiya et al., Citation2020). The way forward may be to separate depersonalisation and emotional exhaustion to determine those at most risk for each component and design targeted interventions (Eckleberry-Hunt et al., Citation2018). Duty hour restrictions have shown mixed results on burnout; however, debriefing curriculums that foster professional development and enhance the quality of care seem to be beneficial (DeChant et al., Citation2019).

Strengths

This overview included the use of comprehensive literature searches, the assessment of a large body of evidence (1,143 primary studies across systematic reviews) worldwide and of several common mental health problems. All included systematic reviews were published from 2012, making the observed findings more applicable to current junior doctors and medical students.

Limitations

Some limitations must be acknowledged. The information gathered from existing systematic reviews varied in terms of study designs, screening tools, demographics of the assessed populations and eligibility criteria. The prevalence of the common mental health problems cannot be precisely determined due to the heterogenous screening tools, student/trainee populations and low methodological rigour of some reviews. It is worth noting that the nature of psychiatric screening tools relies on subjective and self-reported measures with varying cut-off values and, therefore, the reliability and validity of these measures must be interpreted with caution. Full diagnostic interviews are a more reliable assessment method. The heterogeneous study populations varied widely in locations, course structure and cultures, which may introduce various confounding variables that may influence the participation in studies and reporting of common mental health problems. Similarly, the intervention reviews had varying lengths of follow-up times and often, the absence of comparators made it challenging to draw reliable conclusions. Due to time constraints, only English language publications were included, therefore, one non-English review with no translation was not considered; this is acknowledged as a limitation of this overview. Only two reviews compared prevalence rates across groups (i.e. students from other faculties). The degree of overlap between reviews in terms of included studies was not quantified. Finally, the definitions of mindfulness-based interventions and MBSR varied considerably across reviews and between studies included in the same reviews rendering it challenging to make proper comparisons and draw conclusions. Apart from mindfulness-based interventions and MBSR, few attempts have been made to explore other possible interventions.

Future directions and conclusions

Implications for practice

Medical training establishments should recognise that junior doctors and medical students are susceptible to high prevalence rates of common mental health problems. Interventions to mitigate common mental health problems should be offered to junior doctors and medical students, incorporated into medical curricula, and tailored to cultural contexts.

Implications for research

For future research, a consensus on common mental health problem definitions, valid cut-off scores, and validated outcome measures should be consistent across the field; this can be achieved by following the WHO and ICD-10 standardised definitions. Additionally, screening for co-morbid psychiatric disorders (e.g. eating disorders), and accurately reporting the data by following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiological guidelines (von Elm et al., Citation2008).

There is a need to standardise the definitions of mindfulness-based interventions, MBSR and for improved comparators to allow for fair comparisons between interventions and controls. There is a suggested benefit of extending intervention durations to up to 8-weeks (Yusoff, Citation2014) along with implementing longer follow-up periods to understand the long-term effects (Rotenstein et al., Citation2016). Comprehensive baseline diagnostics i.e. clinical interviews may be beneficial to enhance the reporting of pre-existing common mental health problems. Enhanced reporting of intervention studies is required, by following the international CONSORT statement (Schulz et al., Citation2010). Evidence suggests that mindfulness-based interventions may play a role in addressing common mental health problems and, therefore, future research should focus on this theoretical-based intervention and provide more robust evidence on its effects.

Finally, future studies should recruit more males and be conducted in low-middle-income countries to reach robust conclusions. Research on different formats of interventions (mobile-based, online) (Haberer et al., Citation2013) is also desirable.

Unsurprisingly, junior doctors and medical students have high prevalence rates of common mental health problems, which reinforces the need for more focused mental health strategies. Mental health improvements could be achieved by appropriate interventions that would result in a stronger and healthier medical workforce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Component of PICO.

2 Review Protocol.

3 Explanation for study design.

4 Comprehensive literature search strategy.

5 Study selection in duplicate.

6 Data extraction in duplicate.

7 List of excluded studies and justification for the exclusions.

8 Study characteristics.

9 Satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias.

10 Sources of funding.

11 Appropriate methods.

12 Assess potential impact of risk of bias on results.

13 Account for risk of bias when interpreting the results.

14 Satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of any heterogeneity.

15 Publication bias assessed and discussed.

16 Potential sources of conflict of interest.

17 Component of PICO.

18 Review Protocol.

19 Explanation for study design.

20 Comprehensive literature search strategy.

21 Study selection in duplicate.

22 Data extraction in duplicate.

23 List of excluded studies and justification for the exclusions.

24 Study characteristics.

25 Satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias.

26 Sources of funding.

27 Appropriate methods.

28 Assess potential impact of risk of bias on results.

29 Account for risk of bias when interpreting the results.

30 Satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of any heterogeneity.

31 Publication bias assessed and discussed.

32 Potential sources of conflict of interest.

References

- Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 934–948. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003.

- Alvi, T., Assad, F., Ramzan, M., & Khan, F. A. (2010). Depression, anxiety and their associated factors among medical students. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons–Pakistan, 20(2), 122–126. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20378041

- Bacchi, S., & Licinio, J. (2015). Qualitative literature review of the prevalence of depression in medical students compared to students in non-medical degrees. Academic Psychiatry, 39(3), 293–299. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0241-5.

- Bennion, M. R., Baker, F., & Burrell, J. (2022). An unguided web-based resilience training programme for NHS keyworkers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A usability study. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 7(2), 125–129. doi: 10.1007/s41347-021-00225-3.

- Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2014). Is burnout a depressive disorder? A reexamination with special focus on atypical depression. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(4), 307–324. doi: 10.1037/a0037906.

- Card, A. J. (2018). Physician burnout: Resilience training is only part of the solution. Annals of Family Medicine, 16(3), 267–270. doi: 10.1370/afm.2223.

- Carlson, L. E. (2012). Mindfulness-based interventions for physical conditions: A narrative review evaluating levels of evidence. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, 651583–651521. doi: 10.5402/2012/651583.

- Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Marziali, M. E., Lu, Z., & Martins, S. S. (2021). Investigating the effect of national government physical distancing measures on depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic through meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 51(6), 881–893. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000933.

- Chi, X., Bo, A., Liu, T., Zhang, P., & Chi, I. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1034. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01034.

- Chunming, W. M., Harrison, R., MacIntyre, R., Travaglia, J., & Balasooriya, C. (2017). Burnout in medical students: a systematic review of experiences in Chinese medical schools. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 217. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1064-3.

- Coentre, R., & Góis, C. (2018). Suicidal ideation in medical students: Recent insights. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 9, 873–880. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S162626.

- Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A., & Ruggeri, M. (2020). Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 23. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9.

- Cuttilan, A. N., Sayampanathan, A. A., & Ho, R. C. (2016). Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: A systematic review [2000–2015]. Annals of Translational Medicine, 4(4), 72. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.02.07.

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: An overview of systematic reviews. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4S), S49–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020.

- Daya, Z., & Hearn, J. H. (2018). Mindfulness interventions in medical education: A systematic review of their impact on medical student stress, depression, fatigue and burnout. Medical Teacher, 40(2), 146–153. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1394999.

- de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sørlie, T., & Bjørndal, A. (2013). Mindfulness training for stress management: A randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Medical Education, 13(1), 107. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-107.

- DeChant, P. F., Acs, A., Rhee, K. B., Boulanger, T. S., Snowdon, J. L., Tutty, M. A., Sinsky, C. A., & Thomas Craig, K. J. (2019). Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: A systematic review. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 3(4), 384–408. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.006.

- Doll, C. M., Michel, C., Rosen, M., Osman, N., Schimmelmann, B. G., & Schultze-Lutter, F. (2021). Predictors of help-seeking behaviour in people with mental health problems: A 3-year prospective community study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 432. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03435-4.

- Dossey, L. (2007). Debt and health. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 3(2), 83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2006.12.004.

- Eckleberry-Hunt, J., Kirkpatrick, H., & Barbera, T. (2018). The problems with burnout research. Academic Medicine, 93(3), 367–370. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001890.

- Erschens, R., Keifenheim, K. E., Herrmann-Werner, A., Loda, T., Schwille-Kiuntke, J., Bugaj, T. J., Nikendei, C., Huhn, D., Zipfel, S., & Junne, F. (2019). Professional burnout among medical students: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 41(2), 172–183. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457213.

- Fox, S., Lydon, S., Byrne, D., Madden, C., Connolly, F., & O’Connor, P. (2018). A systematic review of interventions to foster physician resilience. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 94(1109), 162–170. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135212.

- Frajerman, A., Morvan, Y., Krebs, M., Gorwood, P., & Chaumette, B. (2019). Burnout in medical students before residency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 55, 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.08.006.

- Frank, C., Land, W. M., Popp, C., & Schack, T. (2014). Mental representation and mental practice. PLoS One, 9(4), e95175. 4, Art. e95175 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095175.

- Galaiya, R., Kinross, J., & Arulampalam, T. (2020). Factors associated with burnout syndrome in surgeons: a systematic review. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 102(6), 401–407. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2020.0040.

- Goodman, M. J., & Schorling, J. B. (2012). A mindfulness course decreases burnout and improves well-being among healthcare providers. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 43(2), 119–128. doi: 10.2190/PM.43.2.b.

- Haberer, J. E., Trabin, T., & Klinkman, M. (2013). Furthering the reliable and valid measurement of mental health screening, diagnoses, treatment and outcomes through health information technology: Health Information Technology and Mental Health Services Research. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(4), 349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.009.

- Harmer, B., Lee, S., Duong, T. v H., & Saadabadi, A. (2022). Suicidal ideation. StatPearls Publishing.

- Hathaisaard, C., Wannarit, K., & Pattanaseri, K. (2022). Mindfulness-based interventions reducing and preventing stress and burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 69, 102997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102997.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9781119536604.

- Hope, V., & Henderson, M. (2014). Medical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: A systematic review. Medical Education, 48(10), 963–979. doi: 10.1111/medu.12512.

- IsHak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., & Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. The Clinical Teacher, 10(4), 242–245. doi: 10.1111/tct.12014.

- Jacob, R., Li, T., Martin, Z., Burren, A., Watson, P., Kant, R., Davies, R., & Wood, D. F. (2020). Taking care of our future doctors: A service evaluation of a medical student mental health service. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 172–110. 1186/s12909-020-02075-8 doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02075-8.

- Jadhakhan, F., Lindner, O. C., Blakemore, A., & Guthrie, E. (2019). Prevalence of common mental health disorders in adults who are high or costly users of healthcare services: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(9), e028295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028295.

- Jafari, N., Loghmani, A., & Montazeri, A. (2012). Mental health of medical students in different levels of training. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(Suppl1), S107–S112. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3399312/

- Jena, A. B., Schoemaker, L., & Bhattacharya, J. (2014). The effect of ACGME resident duty hour reforms on outcomes of physicians after completion of residency. Health Affairs (Millwood), 33(10), 1832–1840. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0318.

- Jia, Q., Qu, Y., Sun, H., Huo, H., Yin, H., & You, D. (2022). Mental health among medical students during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 846789. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846789.

- Jurewicz, I. (2015). Mental health in young adults and adolescents – Supporting general physicians to provide holistic care. Clinical Medicine (London, England), 15(2), 151–154. 107861/clinmedicine.15-2-151 doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-151.

- Rohan, K. J. (2003). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse/overcoming resistance in cognitive therapy. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Khan, M. S., Mahmood, S., Badshah, A., Ali, S., & Jamal, Y. (2006). Prevalence of depression, anxiety and their associated factors among medical students of Sindh Medical College, Karachi, Pakistan. American Journal of Epidemiology, 163(suppl_11), S220–S220. doi: 10.1093/aje/163.suppl_11.S220-c.

- Krishnan, A., Odejimi, O., Bertram, I., Chukowry, P. S., & Tadros, G. (2022). A systematic review of interventions aiming to improve newly-qualified doctors’ wellbeing in the United Kingdom. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 161. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00868-8.

- Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress, 19(3), 192–207. doi: 10.1080/02678370500297720.

- Kunzler, A. M., Kunzler, A. M., Helmreich, I., Chmitorz, A., König, J., Binder, H., Wessa, M., & Lieb, K. (2020). Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD012527. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012527.pub2.

- Kwong, J. C., Dhalla, I. A., Streiner, D. L., Baddour, R. E., Waddell, A. E., & Johnson, I. L. (2005). A comparison of Canadian medical students from rural and non-rural backgrounds. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 10(1), 36–42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15656922

- Lasheras, I., Gracia-García, P., Lipnicki, D. M., Bueno-Notivol, J., López-Antón, R., de la Cámara, C., Lobo, A., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Erratum: Lasheras, I.; et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6603. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9353. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249353.

- Lawlor, S., Low, C., Carlson, M., Rajasekaran, K., & Choby, G. (2022). Burnout and well‐being in otolaryngology trainees: A systematic review. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, 8(2), 118–125. doi: 10.1002/wjo2.21.

- Lei, X., Xiao, L., Liu, Y., & Li, Y. (2016). Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153454.

- Li, Y., Cao, L., Mo, C., Tan, D., Mai, T., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Prevalence of burnout in medical students in China. Medicine, 100(26), e26329. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026329.

- Littlewood, R., Jadhav, S., & Ryder, A. G. (2007). A cross-national study of the stigmatization of severe psychiatric illness: Historical review, methodological considerations and development of the questionnaire. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(2), 171–202. doi: 10.1177/1363461507077720.

- Low, Z. X., Yeo, K. A., Sharma, V. K., Leung, G. K., McIntyre, R. S., Guerrero, A., Lu, B., Sin Fai Lam, C. C., Tran, B. X., Nguyen, L. H., Ho, C. S., Tam, W. W., & Ho, R. C. (2019). Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), 1479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091479.

- Mancevska, S., Bozinovska, L., Tecce, J., Pluncevik-Gligoroska, J., & Sivevska-Smilevska, E. (2008). Depression, anxiety and substance use in medical students in the Republic of Macedonia. Bratislavské Lékarské Listy, 109(12), 568–572. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19348380

- Mao, Y., Zhang, N., Liu, J., Zhu, B., He, R., & Wang, X. (2019). A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 327. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2.

- McConville, J., McAleer, R., & Hahne, A. (2017). Mindfulness training for health profession students—The effect of mindfulness training on psychological well-being, learning and clinical performance of health professional students: a systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 13(1), 26–45. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.10.002.

- McKenzie, S. H., & Harris, M. F. (2013). Understanding the relationship between stress, distress and healthy lifestyle behaviour: A qualitative study of patients and general practitioners. BMC Family Practice, 14(1), 166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-166.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 339(jul21 1), b2535–b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Naithani, M., Khapre, M., Kathrotia, R., Gupta, P. K., Dhingra, V. K., & Rao, S. (2021). Evaluation of sensitization program on occupational health hazards for nursing and allied health care workers in a tertiary health care setting. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 669179. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.669179.

- Naji, L., Singh, B., Shah, A., Naji, F., Dennis, B., Kavanagh, O., Banfield, L., Alyass, A., Razak, F., Samaan, Z., Profetto, J., Thabane, L., & Sohani, Z. N. (2021). Global prevalence of burnout among postgraduate medical trainees: a systematic review and meta-regression. CMAJ Open, 9(1), E189–E200. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200068.

- Natalia, D., & Syakurah, R. A. (2021). Mental health state in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, 208. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1296_20.

- NICE. (2022a). Common mental health problems | Information for the public | Common mental health problems: identification and pathways to care | Guidance | NICE. Retrieved July 3 from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123/ifp/chapter/common-mental-health-problems

- NICE. (2022b). Definition | Background information | Generalized anxiety disorder | CKS | NICE. Retrieved June 23 from https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/generalized-anxiety-disorder/background-information/definition/

- NICE. (2022c). Depression | Health topics A to Z | CKS | NICE. Retrieved June 23 from https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression/

- NICE. (2022d). Introduction | Obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: treatment | Guidance | NICE. Retrieved June 23 from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31/chapter/Introduction

- Nochaiwong, S., Ruengorn, C., Thavorn, K., Hutton, B., Awiphan, R., Phosuya, C., Ruanta, Y., Wongpakaran, N., & Wongpakaran, T. (2021). Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 10173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8.

- Pacheco, J. P., Giacomin, H. T., Tam, W. W., Ribeiro, T. B., Arab, C., Bezerra, I. M., & Pinasco, G. C. (2017). Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999), 39(4), 369–378. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223.

- Pisaniello, M. S., Asahina, A. T., Bacchi, S., Wagner, M., Perry, S. W., Wong, M., & Licinio, J. (2019). Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance and specialty choice: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(7), e029980. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029980.

- Pollock, M., Fernandes, R. M., Becker, L. A., Pieper, D., & Hartling, L. (2022). Chapter V: Overviews of reviews. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version. 6.3.

- Prabhu, A. M., & Rashad, I. (2021). More research needed into long-term medical student mental health during COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. BJPsych Bulletin, 45(3), 194–195. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2021.49.

- Puthran, R., Zhang, M. W. B., Tam, W. W., & Ho, R. C. (2016). Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Medical Education, 50(4), 456–468. doi: 10.1111/medu.12962.

- Quek, T. T., Tam, W. W., Tran, B. X., Zhang, M., Zhang, Z., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2019). The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152735.

- Rao, D., Feinglass, J., & Corrigan, P. (2007). Racial and ethnic disparities in mental illness stigma. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(12), 1020–1023. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815c046e.

- Regehr, C., Glancy, D., Pitts, A., & LeBlanc, V. (2014). Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: A review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(5), 353–359. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000130.

- Rose, S. A., Sheffield, D., & Harling, M. (2018). The integration of the workable range model into a mindfulness-based stress reduction course: A practice-based case study. Mindfulness, 9(2), 430–440. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0787-x.

- Rotenstein, L. S., Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J., Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. A. (2016). Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(21), 2214–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324.

- Santabárbara, J., Olaya, B., Bueno-Notivol, J., Pérez-Moreno, M., Gracia-García, P., Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., & Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. (2021). Prevalence of depression among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Medica de Chile, 149(11), 1579–1588. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872021001101579.

- Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., & Moher, D. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Medicine, 7(3), e1000251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251.

- Sekhar, P., Tee, Q. X., Ashraf, G., Trinh, D., Shachar, J., Jiang, A., Hewitt, J., Green, S., & Turner, T. (2021). Mindfulness‐based psychological interventions for improving mental well‐being in medical students and junior doctors. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12(12), CD013740. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013740.pub2.

- Seo, C., Di Carlo, C., Dong, S. X., Fournier, K., & Haykal, K. (2021). Risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among medical students: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 16(12), e0261785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261785.

- Shah, H. P., Salehi, P. P., Ihnat, J., Kim, D. D., Salehi, P., Judson, B. L., Azizzadeh, B., & Lee, Y. H. (2023). Resident burnout and well-being in otolaryngology and other surgical specialties: Strategies for change. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 168(2), 165–179. 1945998221076482. doi: 10.1177/01945998221076482.

- Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., Kristjansson, E., & Henry, D. A. (2017). AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 358, j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008.

- Sheldon, E., Simmonds-Buckley, M., Bone, C., Mascarenhas, T., Chan, N., Wincott, M., Gleeson, H., Sow, K., Hind, D., & Barkham, M. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 287, 282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.054.

- Shiralkar, M. T., Harris, T. B., Eddins-Folensbee, F. F., & Coverdale, J. H. (2013). A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 37(3), 158–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.12010003.

- Sousa, G. M. d., Tavares, V. D. d O., de Meiroz Grilo, M. L. P., Coelho, M. L. G., Lima-Araújo, G. L. d., Schuch, F. B., & Galvão-Coelho, N. L. (2021). Mental health in COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-review of prevalence meta-analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 703838. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703838.

- Søvold, L. E., Naslund, J. A., Kousoulis, A. A., Saxena, S., Qoronfleh, M. W., Grobler, C., & Münter, L. (2021). Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: An urgent global public health priority. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 679397. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397.

- Statistics – NHS Digital. (2022, January). NHS Sickness Absence Rates. NHS.UK. Retrieved 2022, June 1, from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-sickness-absence-rates/january-2022-provisional-statistics

- Tam, W., Lo, K., & Pacheco, J. (2019). Prevalence of depressive symptoms among medical students: overview of systematic reviews. Medical Education, 53(4), 345–354. doi: 10.1111/medu.13770.

- Virgili, M. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions reduce psychological distress in working adults: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Mindfulness, 6(2), 326–337. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0264-0.

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

- Walsh, A. L., Lehmann, S., Zabinski, J., Truskey, M., Purvis, T., Gould, N. F., Stagno, S., & Chisolm, M. S. (2019). Interventions to prevent and reduce burnout among undergraduate and graduate medical education trainees: A systematic review. Academic Psychiatry, 43(4), 386–395. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01023-z.

- Weibelzahl, S., Reiter, J., & Duden, G. (2021). Depression and anxiety in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology and Infection, 149, e46. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821000303.

- Wells, S. E., Bullock, A., & Monrouxe, L. V. (2019). Newly qualified doctors’ perceived effects of assistantship alignment with first post: A longitudinal questionnaire study. BMJ Open, 9(3), e023992. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023992.

- Witt, K., Boland, A., Lamblin, M., McGorry, P. D., Veness, B., Cipriani, A., Hawton, K., Harvey, S., Christensen, H., & Robinson, J. (2019). Effectiveness of universal programmes for the prevention of suicidal ideation, behaviour and mental ill health in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(2), 84–90. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300082.

- Yogeswaran, V., & El Morr, C. (2021). Effectiveness of online mindfulness interventions on medical students’ mental health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 2293. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12341-z.

- Yusoff, M. S. B. (2014). Interventions on medical students’ psychological health: A meta-analysis. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 9(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2013.09.010.

- Zeng, W., Chen, R., Wang, X., Zhang, Q., & Deng, W. (2019). Prevalence of mental health problems among medical students in China: A meta-analysis. Medicine, 98(18), e15337. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015337.

- Zhou, A. Y., Panagioti, M., Esmail, A., Agius, R., Van Tongeren, M., & Bower, P. (2020). Factors associated with burnout and stress in trainee physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), e2013761. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13761.

Appendix 1.

Table of acronyms.

Appendix 2.

Search strategy MEDLINE (ovid).

Prevalence

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions <1946 to May 16, 2022>

Interventions

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions <1946 to May 16, 2022>

Appendix 3.

Data extraction forms.

Prevalence

Interventions

Appendix 4.

Summary Table on the mental health outcome measuring tools – prevalence.

AKUADS – Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale.

ASLEC – Adolescents Self-Rating Life Events Checklist.

AVEM – Arbeitsbezogene Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster i.e. The Measure of Coping Capacity Questionnaire.

BAI – Beck’s Anxiety Inventory.

BDI – Beck’s Depression Inventory.

BDI TMAS – Beck’s Depression Inventory Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale.

BSI – Beck’s Scale for Suicide Ideation.

BSI-ANX – Brief Symptom Inventory Anxiety.

BSI-DEP – Brief Symptom Inventory Depression.

CBI – Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.

CCSAS – Chinese College Student Adjustment Scale.

CES-D – Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale.

DAS-21 – Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21.

DDRS – Depression Rate Scale.

DEQ – Depression Experience Questionnaire.

DSI – Depression Screening Instrument.

EPQ – Extended Project Qualification.

EPWBI and PWBI – Expanded Physician Well Being index.

EST-Q – Emotional State Questionnaire.

GAD-7 – Generalised anxiety Disorder Scale.

GHQ – General Health Questionnaire.

GHQ-12 SOC – the Twelve Item General Health Questionnaire Sense of Coherence.

HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

HAM-A – Hamilton Anxiety Rate Scale.

HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rate Scale.

HESI – Higher Education Stress Inventory.

HP5-I – Health Personality perspective inventory.

HRSR – Health related self-report.

IPAT – Anxiety Scale Intensive Care Psychological Assessment Tool Anxiety Scale.

K10 – Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

LRS – Lian Rong Survey.

LSSI – Lipp’s Stress Symptoms Inventory.

MBI – Maslach Burnout inventory.

MBI-HSS – Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey.

MBI-SS – Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey.

MDI – Major Depression Inventory.

MHI-5 – Mental Health Inventory.

Mini – Mini Z Instrument.

OCI-R – Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised.

OLBI – Oldenburg Burnout Inventory.

PBSE-scale – Performance-based self -esteem.

PHQ-9 – Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

PSS – Perceived Stress Scale.

QOLS – Quality of Life Scale.

SAS – Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.

SCL-90 – Symptom Checklist -90.

SDS – Self-rate Depression Scale.

SIAS – Social Interaction Anxiety Scale.

SPFI – Suicide Prevention Fundamental instructions.

SQ-48-A – Symptom Questionnaire 48 Anxiety.

SRQ-20 – Self Reporting Questionnaire.

STAI/STAI-T – Sate-Tait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Scale.

SWLS GAD – Satisfaction with Life Scale Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale.

ZDS – Zung Depression Scale.

ZSAS – Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

Appendix 5.

Summary Table on the mental health outcome measuring tools – interventions.

BAI – Beck’s Anxiety Inventory.

BDI – Beck’s Depression Inventory.

BOS-II – Burnout Screening Scale.

BSI – Brief Symptom Inventory.

BSI – Brief Symptom Inventory.

CBI – Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.

CES-D – Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale.

DASS – Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale.

ESSI – Stress System Instrument.

GAD-7 – Generalised anxiety Disorder Scale.

GHQ – General Health Questionnaire.

HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

MASQ – Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire.

MBI – Maslach Burnout inventory.

MBI SCL-5 – Maslach Burnout inventory Symptom Checklist 5.

MSSQ-20 – Medical Student Stress Questionnaire.

PCS – Physical Component Summary.

PHQ-9 – Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

PMSS – Perceived Medical School Stress Instrument.

POMS – Profile of Mood State.

PRIME-MD – Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders.

PSMS – Perceived Stress Management Skills.

PSS – Perceived Stress Scale.

SCL-90 – Symptom Checklist -90.

SSCS – Stress-Strain Coping Support Model.

STAI – Sate-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

TAI – Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Appendix 6.

AMSTAR-2 quality assessment summary – prevalence.

Appendix 7.

AMSTAR-2 quality assessment summary – interventions.

Appendix 8.

Definitions of CMHP and prevalence.

Appendix 9. Definitions of interventions.