Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that financial crises and poor mental health are reciprocally related, but no systematic review has been conducted to synthesise the existing literature on the impact of national and international financial crises on population-level mental health and well-being.

Aims

The aim of this study was to systematically review the available literature on the global impact of financial crises on mental health and well-being outcomes.

Methods

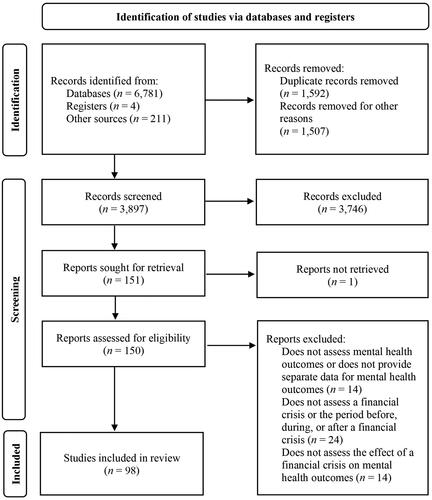

After registration on PROSPERO, a systematic search was conducted in PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Wiley, and Web of Science for papers published until 21 November 2022. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement, 98 papers were identified as meeting eligibility criteria. Included studies were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) and results were presented in a formal narrative synthesis.

Results

Our findings show that financial crises are significantly associated with well-being and occurrence of psychological conditions. Several socio-demographic, cultural, and country-specific characteristics played a crucial role in the prevention of population mental health decline in periods of financial crises.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this review, evidence-based recommendations were developed to guide the design of policy actions that protect population mental health during and after financial crises.

Introduction

Although it is now well-known that poor mental health is associated with poverty, inequality, deprivation, and other socio-economic determinants (WHO, Citation2011), systematic research on the impact of hardship on mental health has grown only in recent decades, with mental health economic reports reaching over 4000 publications in 2019, compared to approximately 100 in 1999 (Knapp & Wong, Citation2020). The accumulating evidence suggests that financial, economic, and political crises are a reality that inevitably affects mental health. Direct socio-economic consequences of financial crises, such as unemployment, job insecurity, poor education, and debt have been repeatedly associated with the worsening of mental health and increased psychopathology (Christodoulou & Christodoulou, Citation2013).

For example, a recent non-systematic review on financial crises and mental health reported that depression, stress, and anxiety were the most common outcomes of financial crises (Volkos & Symvoulakis, Citation2021), sometimes presenting after, rather than during, the crisis (Sargent-Cox et al., Citation2011). Similarly, a non-systematic review on the short- and long-term impacts of economic crises on mental health suggests that unemployment, reduced staff and wages, and increased workload constitute risk factors for poor mental health, with depression and suicide being the most common outcomes worldwide (Marazziti et al., Citation2021). Finally, a systematic review from 2016 reported that economic recessions up to 2014 were potentially associated with a greater prevalence of mental health issues, including common mental health conditions, substance disorders, and suicidal behaviour (Frasquilho et al., Citation2015).

Financial and socio-economic crises affect mental health by weakening the protective factors that help sustain societal development and well-being (e.g. welfare protection, job security, healthy lifestyle) and consequently by strengthening the risk factors that contribute to increased psychiatric morbidity (e.g. home and job insecurity, debt, poverty, increased social inequalities, and exclusion) (Paleologou et al., Citation2018). Certain socially and economically disadvantaged groups—including children, older adults, single parents, ethnic minorities, and migrants—seem to be especially vulnerable to hardship-related poor mental health (Bøe et al., Citation2014; Burgard & Hawkins, Citation2014; Burns & Gimpel, Citation2000; Evans-Lacko et al., Citation2013; Sargent-Cox et al., Citation2011; WHO, Citation2011). This is why, in 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed these and other related factors among the determinants of mental health (WHO, Citation2011).

It should be noted that the association between mental health and financial hardship is reciprocal. That is, poverty can lead to mental illness, and mental illness can make it harder to succeed economically and financially (Ridley et al., Citation2020). These associations have been observed in culturally diverse studies and with consistency across time. For instance, increased suicides were reported in East and Southeast Asia during the economic crisis of the 1990s (Chang et al., Citation2009), suicide rates were shown to rise in China following the socio-economic reforms that started in 1978 (Phillips et al., Citation1999), and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 was linked to poorer psychological health in the Australian population (Sargent-Cox et al., Citation2011), as well as in European and American countries (Volkos & Symvoulakis, Citation2021). Similarly, the Greek debt crisis that spanned the period between 2009 and 2018 has been associated with increased suicide rates (Kubrin et al., Citation2022), whereas financial threat due to the economic crisis in Portugal between 2011 and 2014 has been associated with anxiety, stress, and depression (Viseu et al., Citation2021). More recently, global financial, economic, and political uncertainties have further increased concerns regarding the effects of global financial crises on mental health (AlNemer, Citation2023; Kam et al., Citation2023; Williams & Dienes, Citation2022).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to systematically review the available literature on the global impact of financial crises on mental health and well-being outcomes, and to create evidence-based recommendations for mitigating mental health concerns during and after such crises. To the authors’ knowledge, only one systematic review has investigated the impact of multiple financial crises on mental health outcomes (Frasquilho et al., Citation2015). However, given recent (often interconnected) world-wide events, including the energy crisis, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War, and various cost-of-living crises, the current study sought to provide an updated and rigorous (e.g. including a quality assessment) review of risk and protective factors associated with population mental health, and how to support individuals during future financial crises. Moreover, this review will expand on Frasquilho et al.’s (Citation2015) search design to include a broader range of mental health and well-being outcomes (see the Data Sources and Search Strategies section).

Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA; Page et al., Citation2021) and was preregistered on PROSPERO (ref no. CRD42022372137) prior to commencement (16 November 2022).

Data sources and search strategies

Searches were conducted for journal articles published in English using the databases PsycINFO (accessed via EBSCO), MEDLINE (accessed via EBSCO), Wiley, and Web of Science from their inception until 21 November 2022. Furthermore, we searched for unpublished studies uploaded to PsyArXiv and scanned the reference sections of the included articles to identify additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. Boolean combinations and alternative spellings of the following search terms were used: financ*; money; monetary; poverty; cost of living; debt; job insecurity; income insecurity; emotional health; mental health; stress; anxiety; depress*; well-being; worry; distress; psych*; dysfunction; mood; suicide; isolation; self-harm; vulnerable. The full search strategy can be found in Supplementary Materials Appendix A.

Study eligibility criteria

We included cohort studies, longitudinal studies, cross-sectional studies, case reports, and other quantitative studies that examined the impact of national or international financial crises on population-level mental health and well-being outcomes. A broad range of mental health and well-being outcomes was considered, including stress, anxiety, depression, worry, self-harm, suicide, general mood, dysfunction, psychological distress, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being.

We excluded: (1) review papers, commentaries, opinion pieces, editorials, and qualitative studies; (2) papers that did not assess the direct relationship between financial crises and target outcomes (e.g. studies that had been conducted during a financial crisis, but that did not examine the relationship/effect of the financial crisis or related predictors on target outcomes; studies that did not compare levels of mental health concerns with pre-, during, or post-crisis levels); and (3) papers related to idiographic financial hardship, rather than population-level events (e.g. student debt, unemployment, low income).

Notably, although other global events can lead to financial difficulties (e.g. natural disasters, pandemics; Kämpfen et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2011), these papers were excluded for two main reasons. First, the focus of the current review was on primary financial crises and their direct impact on mental health and well-being. As such, financial difficulties caused by other events were beyond the scope of the current review. Second, such events are likely to have distinct effects on population-level mental health that go beyond their impact on financial well-being. For example, several papers have demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on mental health (e.g. anxiety and depression) due to numerous factors (e.g. job loss, fear of being quarantined, lack of social support; De Bruin, Citation2021; Gibson et al., Citation2021; Kämpfen et al., Citation2020; Yang & Ma, Citation2021). Although some of these factors intersect with financial difficulties, significant (non-financial) global events likely have an additive and complex impact on mental health.

Study selection and data extraction

The first three authors screened the retrieved papers and extracted the relevant data from eligible studies. After running the search, duplicates and incomplete search results were excluded and the remaining titles and abstracts were screened against the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. This was followed by full-text screening to remove any further irrelevant papers. When all the studies to be included were identified, data were extracted into a specially designed table shared by the authors.

The following data were extracted from the included studies: (1) study information (authors, year of publication, type of financial crisis, country); (2) participant demographics (sample, gender, age, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status); (3) study characteristics (design, mental health outcomes); and (4) results related to mental health and well-being. For studies that included inferential statistical outcomes, a p-value < .05 was considered significant. The authors held regular meetings to discuss uncertainties and clarify eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies in selecting the final papers for inclusion and extracting the data were resolved through discussion and consultation with the full review team.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., Citation2018). The MMAT is designed for the methodological quality appraisal of systematic mixed method reviews including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies that are based on empirical data only. The MMAT criteria include an assessment of quality across two screening questions for all study designs: (1) “Are there clear research questions?” and (2) “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?”, and five additional domains that differ across study types (Hong et al., Citation2018). Each screening question and domain are scored on a categorical scale (“yes”, “no”, “can’t tell”). All studies are required to pass the screening questions and further appraisal is not recommended when the answer is “no” or “can’t tell” to one or both screening questions (Hong et al., Citation2018). No studies were excluded based on the screening questions in the current review.

The first three authors independently assessed two thirds of all studies, such that each study was assessed by two authors. In line with previous studies (Usher et al., Citation2020), a score for the overall quality assessment was calculated as a high, medium, or low quality based on the total number of “yes” responses across the seven categories, such that 6–7 “yes” responses = high quality study, 3–5 “yes” responses = medium quality study, and <3 “yes” responses = low quality study. Cohen’s kappa (κ; Cohen, Citation1960) was calculated to determine interrater reliability, showing good agreement between total scores (83.7%; κ = 0.716, p < .001). Discrepancies were due to differences in interpretation of criteria and were resolved through discussion, and with the involvement of all authors, until a 100% agreement in coding was reached.

Results

Paper selection

As of November 21, 2022, the search protocol yielded 6,996 papers (see ). After removing duplicates (n = 1592) and incomplete or non-relevant records (n = 1507), 3897 papers were screened based on the title and abstract. Of these, 3746 were excluded and 151 were sought for retrieval, of which one report could not be retrieved. In total, 150 articles were assessed for eligibility. Fourteen papers were excluded because they did not assess mental health outcomes or did not provide separate data for mental health outcomes (e.g. aggregated mental health-related mortality data with other causes of mortality); 24 studies were excluded because they did not assess a financial crisis or the period before, during, or after a financial crisis; and 14 studies were excluded because they did not assess the effect of a financial crisis on mental health outcomes.

Study characteristics

A final sample of 98 studies was included in this review (see ), consisting of 79 repeated cross-sectional studies, 13 longitudinal studies, 3 cross-sectional studies, 1 cohort study, 1 ecological study, and 1 mixed method study. The studies were conducted across Europe (n = 61), North America (n = 10), Asia (n = 7), and Australia (n = 5), with some studies conducted in multiple countries (n = 15). The financial crises explored included the Asian Economic Crisis (1997–1998; n = 2), Global Financial Crisis (2007–2008; n = 79), Greek Government Debt Crisis (2007–2008; n = 2), Swedish Economic Recession (1990–1994; n = 4), Finnish Economic Recession (1991–1993; n = 3), South-Korean Financial Crisis (1997; n = 2), and other periods of economics recession, austerity, and financial or banking crises (n = 6). Most studies investigated the effect of financial crises on suicide rates (n = 48), depression (n = 30), and anxiety (n = 14), with fewer studies considering other mental health outcomes, including stress (n = 10), life satisfaction (n = 5), self-reported well-being (n = 4), and sleep quality (n = 3).

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

Study quality

Based on the MMAT matrix, 86 studies were classified as quantitative non-randomised (see ), 11 studies were classified as quantitative descriptive (see ), and one study was classified as mixed methods (see ). Overall, 87 studies were rated as high quality, 11 studies were rated as medium quality, and no studies were rated as low quality.

Table 2. Quality assessment of quantitative non-randomised studies using the mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Table 3. Quality Assessment of quantitative descriptive studies using the mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Table 4. Quality assessment of mixed methods studies using the mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

The effect of financial crises on suicide-related outcomes

Suicide rates were the most commonly measured outcomes in the studies reviewed (n = 41 of a possible n = 98). The majority of these studies (n = 30) found that suicide rates increased both during and after financial crises (e.g. Branas et al., Citation2015; Economou et al., Citation2011; Kim, Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2004; Kubrin et al., Citation2022). In most cases, unemployment—especially among men and in countries where unemployment or average income was already low—(e.g. Antonakakis & Collins, Citation2014; Milner et al., Citation2014; Reeves et al., Citation2012), economic distress (Economou et al., Citation2011), reductions in government expenditure (such as fiscal austerity measures) (Antonakakis & Collins, Citation2014; Branas et al., Citation2015; Kubrin et al., Citation2022), and living in a country with lower social spending (Baumbach & Gulis, Citation2014; Norström & Grönqvist, Citation2015; Toffolutti & Suhrcke, Citation2014), were most commonly associated with suicide rates. As part of a multi-country study on the impacts of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, Stuckler et al. (Citation2011) noted that “countries facing the most severe financial reversals of fortune… had greater rises in suicides” (p. 125).

Other risk factors included type of employment; Milner et al. (Citation2015) found that manual workers in particular (e.g. labourers, farmers, machine operators, and technical and trade workers) were at an increased risk of suicide. However, Kim (Citation2021) found that similar groups (namely skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers) in South Korea were actually at a sustained reduction in suicides, though the authors noted that this was “following the implementation of paraquat [a toxic chemical widely used in herbicide] controls since 2005” (p. 5). Interestingly, two papers found that the highest relative increase in suicide rates was among managerial workers, though this is likely due to the fact that suicide rates for such professions were typically much lower pre-crisis (Chan et al., Citation2014; Kim, Citation2021).

Perhaps relatedly, age also appears to be a risk factor for suicide, though evidence is mixed as to who is at greatest risk. Antonakakis and Collins (Citation2014), Chang et al. (Citation2013), Corcoran et al. (Citation2015), Khang et al. (Citation2005), Lopez Bernal et al. (Citation2013), and Pompili et al. (Citation2014) found that those of early working age were at significant increased risk (potentially due to insecure work and lower income as a result of the crisis). However, Chang et al. (Citation2013) found that older working adults were at greater risk in certain countries, Khang et al. (Citation2005) found that retired adults became at increased risk in the long-term (which they attributed to “worsening old-age poverty associated with neo-liberal structural adjustment after the economic crisis”; p. 1299), and Pompili et al. (Citation2014) found that adults aged 65+ (which may include both working and retired older adults) were at increased risk. Meanwhile, it should be noted that Chang et al. (Citation2009), Córdoba-Doña et al. (Citation2014), and Saurina et al. (Citation2015) found that adults of all ages (including retiring age) were at risk. The reason for these disparities is unclear, though authors have suggested that cultural and/or national differences may play a role; for example, due to proportionally larger increases in unemployment within certain groups across countries (Chang et al., Citation2009). Other reasons may include traditional gender roles in certain cultures (Córdoba-Doña et al., Citation2014) or differential support for different people based on age, health, and marital status (factors that make up an individual’s “personal identity”, which has shown to strongly relate to vulnerability to the negative effects of a socio-economic crisis; Merzagora et al., Citation2016).

Notably, five studies found evidence of a decrease in overall suicide rates (Economou et al., Citation2016a; Hagquist, Citation1998; Hintikka et al., Citation1999; López-Contreras et al., Citation2019; Neumayer, Citation2004), four found no change in suicide trends from pre- to post-crises (Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Citation2020; Harper & Bruckner, Citation2017) or between pre- and during crises (Mattei et al., Citation2014; Merzagora et al., Citation2016), and three reported an increase post-crises only (Alvarez-Galvez et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Garcy & Vagerö, Citation2013). These apparent contradictions may reflect the quality of countries’ welfare support systems (Alvarez-Galvez et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Citation2020; Hagquist, Citation1998) and economic prosperity (Alvarez-Galvez et al., Citation2021), national changes to prevention and health services (Hagquist, Citation1998), changes in social norms (including a reduction in stigma/harmful social expectations or in attitudes to behaviours that may increase the risk of suicide) (Hintikka et al., Citation1999; Mattei et al., Citation2014), and the long-term impacts of continued unemployment (Garcy & Vagerö, Citation2013). Further, findings may also be impacted by study methodology (Alvarez-Galvez et al., Citation2017; Harper & Bruckner, Citation2017; Neumayer, Citation2004) (by multiple authors’ admissions, suicide data is not always perfect and modelling suicide mortality is a complex science, whereby different approaches yield different rates and predictions; see Harper and Bruckner (Citation2017) and Merzagora et al. (Citation2016) for discussions) or study focus (Merzagora et al. (Citation2016), for example, looked specifically at the relationship between employment status/health status and suicide risk during the economic crisis and did not examine wider trends).

In studies that showed an overall increase in suicide rates, female suicide rates were often reported to remain stable or even to decrease (e.g. Corcoran et al., Citation2015; Konieczna et al., Citation2022; Pompili et al., Citation2014; Rachiotis et al., Citation2015). A key factor driving these differences may be men’s relationships with employment; among men, unemployment was a consistent suicide risk factor during financial crises (e.g. Coope et al., Citation2014; Iglesias García et al., Citation2014; Kubrin et al., Citation2022; Norström & Grönqvist, Citation2015; Rachiotis et al., Citation2015). Only one study reported an association between suicide rates and unemployment independently of sex (Garcy & Vagerö, Citation2013). When female suicide mortality did increase, rates were still typically less pronounced compared to men (López-Contreras et al., Citation2019; Mohseni-Cheraghlou, Citation2016; Reeves et al., Citation2015; Saurina et al., Citation2015), although two multi-country studies reported increased rates among women from Eastern European countries (Norström & Grönqvist, Citation2015) and other middle-income countries (Mohseni-Cheraghlou, Citation2016). Such increases were explained in both studies by the fact that unemployment caused material deprivation that affected the entire household, thus rendering suicide “contagious”, especially among close family members.

Unlike suicide rates, suicide attempts generally increased during financial crises among both men and women (Córdoba-Doña et al., Citation2014; De Vogli et al., Citation2013; Economou et al., Citation2011, Citation2016b; Mattei et al., Citation2014). The presence of major depression, low levels of interpersonal trust, having lower education, and previous suicide attempts increase the odds of suicidal ideation, especially in men (Economou et al., Citation2013, Citation2016b). Unemployment status was also significantly associated with increased rates of suicide attempts among men in particular (Mattei et al., Citation2014). Only Ostamo and Lönnqvist (Citation2001) found no change in suicide attempt rates (and a decrease among men). However, the authors could not offer an explanation for this, and cautioned about the generalisability of their findings in relation to evidence from other studies.

Information on protective factors for suicide, suicide ideation, or suicide attempts during financial crises was found to be extremely limited. Studies have so far observed suicide rates to be lower in individuals with unemployment pay (Hagquist, Citation1998) and among those with a positive physical and psychological health status (Merzagora et al., Citation2016), while national “prosperity-related events” (e.g. when Greece was accepted into the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union) seem to act as a buffer, at least for men (Branas et al., Citation2015).

The effect of financial crises on mental disorders (including disorder symptoms)

Beyond suicide, there is a plethora of evidence to show that financial crises have a significant impact on people’s mental health. Gili et al. (Citation2013) found that the prevalence of a range of mental disorders (including major depression, generalised anxiety, and somatoform and alcohol-related disorders) increased over the course of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Economou et al. (Citation2013, Citation2016b) and Wang et al. (Citation2010) also identified an increase in the prevalence of major depression during this period. Relatedly, two studies demonstrated an increase in major depressive episodes (MDEs), though while Madianos et al. (Citation2011) found that those experiencing economic hardship were most at risk, Lee et al. (Citation2010) suggested more diverse, occasionally opposing, groups of individuals as being at risk (for example, the authors found that married, cohabiting, divorced, and widowed individuals were all at an increased risk for an MDE).

Hospitalisations also seemingly increased from pre- to post-crisis, especially among women and individuals on a low income (Bonnie Lee et al., Citation2017). However, Iglesias García et al. (Citation2014) reported that general demand for mental health services decreased. Interestingly, unemployment was not associated with this demand, potentially suggesting that people may actively avoid seeking help during this period, which could also explain the increases in hospitalisation. Further supporting this idea, Corcoran et al. (Citation2015) found that self-harm increased significantly as a result of a financial crisis, though young men (aged 25–44 years) were particularly at risk of hurting themselves.

General anxiety and depression (including anxiety and depression symptoms, sometimes defined as “psychological functioning”) become especially prevalent during times of financial crisis (e.g. Konstantakopoulos et al., Citation2019; Laliotis et al., Citation2016; Urbanos-Garrido & Lopez-Valcarcel, Citation2015). Anti-depressant usage also increased, particularly among those who lost high levels of stock ownings (McInerney et al., Citation2013). Sargent-Cox et al. (Citation2011), meanwhile, reported that anxiety and depression symptoms decreased from pre- to post-crisis among those who reported an impact as a result of the economic slowdown, while McLaughlin et al. (Citation2012) found that exposure to foreclosure during the first year of a crisis was associated with an increase in those same symptoms during later turbulent years. The impacts of austerity measures seem to trigger an increase in anxiety and depression in women (Thomson et al., Citation2018), but have shown to stabilise rates in men of younger and older working age during the same period (Thomson & Katikireddi, Citation2018). An increase in depressive symptoms was particularly noticeable among those on lower income, those with lower education, those with chronic disease, unemployed individuals, women, and those who were widowed/divorced (Mylona et al., Citation2014), which may explain differences between countries differentially impacted or able to support their population during times of crisis (Reibling et al., Citation2017).

There are a number of reasons why mental health challenges may arise, not least due to issues around work. Gili et al. (Citation2013) found that unemployment (as well as mortgage repayment difficulties and evictions) predicted risk of mental disorders. Others that found associations between unemployment and mental health problems include Barr et al. (Citation2015), Buffel et al. (Citation2015), Bacigalupe et al. (Citation2016), and Rahmqvist and Carstensen (Citation1998). In fact, a rise in unemployment following a financial crisis was shown to predict the prevalence of anxiety and depression among the general population (Astell-Burt & Feng, Citation2013), while long-term unemployment during times of crisis appeared to increase one’s mental health risk more than long-term unemployment would have done before times of crisis (Urbanos-Garrido & Lopez-Valcarcel, Citation2015). A loss of a job during a crisis was also positively associated with depressive symptoms (Riumallo-Herl et al., Citation2014). Even among the employed, negative impacts associated with working in the private sector, having a lower income, a bank loan, an increased workload, seeing company profit reductions or stock market losses, being of an older age, or being “mobbed” at work can lead to increases in depression and anxiety levels (Avčin et al., Citation2011). Similarly, downsizing, salary reductions, being transferred to another department, and being assigned new tasks due to financial pressures related to a financial crisis were all positively associated with psychological distress (Snorradóttir et al., Citation2013). Increases in workload and changes in non-financial benefits of work were also positively associated with mental distress (Kronenberg & Boehnke, Citation2019). Meanwhile, being a student, a manual worker, a customer service representative, a specialist or a manager, or having a lower level of education, as well as being from a lower social class or being expected to be a “breadwinner” were also associated with various degrees of distress and disorder (Bacigalupe et al., Citation2016; Barr et al., Citation2015; Bartoll et al., Citation2014; Snorradóttir et al., Citation2013). Interestingly, Shi et al. (Citation2011) found that anxiety increased for part-time workers, but that depression actually decreased among full-time workers.

Other factors influencing the relationship between financial crises and mental health outcomes include being in a household with more children (Snorradóttir et al., Citation2013), seeing a decline in housing wealth (Yilmazer et al., Citation2015), food insecurity (Paleologou et al., Citation2018), a decrease in “financial well-being” (Swift et al., Citation2020), problems with a partner, uncertain future orientation, poor physical health, and use of psychoactive drugs (at least among men) (Viinamäki et al., Citation2000). Gender may also play a role, as women (on balance) seem to be at greater risk of poor mental health outcomes. Drydakis (Citation2015), Friedman and Thomas (Citation2009), Hauksdóttir et al. (Citation2013), Katikireddi et al. (Citation2012), Pfoertner et al. (Citation2014), and Snorradóttir et al. (Citation2013) found women to be at greater risk of poor mental health compared to men. However, timings may influence this (Economou et al. (Citation2016b) found that in the early years of the Global Financial Crisis, women manifested higher rates of major depression than men, but by 2013, men aged 35–44 years had the highest prevalence of depression), as might men’s relationship with employment (e.g. Bacigalupe et al., Citation2016; Buffel et al., Citation2015; Rahmqvist & Carstensen, Citation1998). Interestingly, findings are also mixed regarding the impact of age (e.g. Rahmqvist & Carstensen, Citation1998; Thomson & Katikireddi, Citation2018; Viinamäki et al., Citation2000; Wilkinson, Citation2016), education (e.g. Friedman & Thomas, Citation2009; Hauksdóttir et al., Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2010; Mylona et al., Citation2014), and marital status (Lee et al., Citation2010; Snorradóttir et al., Citation2013; Viinamäki et al., Citation2000; Wilkinson, Citation2016). These contrasting results likely reflect nuances in income, access to financial or familial support, job difficulties and job security, and the quality of, or pressures on, one’s primary relationship(s).

Despite mixed findings regarding the impact of education on risk for distress and disorders, Neocleous and Apostolou (Citation2021) found that those with higher education (particularly social service professionals) reported less impact of the crisis. Similarly, Wilkinson’s (Citation2016) findings indicate that high quality social support may be important for depression and anxiety rates, a result supported by Snorradóttir et al. (Citation2013), who found support from friends or family was negatively associated with psychological distress. A final protective factor was an ability to trust others; Saville (Citation2021) found that this aspect of “ecological social capital” (but not a sense of belonging) buffered against depression.

The effect of financial crises on other mental health outcomes (including life satisfaction, well-being, stress, and sleep)

Beyond mental disorders and related symptomatology, a number of studies examined other aspects of people’s general well-being, but results varied. Studies focusing on life satisfaction, for example, reported contrasting results regarding the effect of financial crises. Specifically, two studies found lower life satisfaction post-crisis compared to the pre-crisis period (Boyce et al., Citation2018; Halvorsen, Citation2016), one study found life satisfaction remained stable during and after a period of financial crisis (Mertens & Beblo, Citation2016), and one study reported stable pre-/post-crisis life satisfaction, but a decline in positive psychological health after a crisis (Bayliss et al., Citation2017). Declines have been observed especially in adults, those with a pre-existing sickness or disability, and those on lower incomes (Bayliss et al., Citation2017; Boyce et al., Citation2018), which may explain these differences. Women reported lower life satisfaction in one study (Bayliss et al., Citation2017), while unemployment was also related to lower life satisfaction in this and one other study (Bayliss et al., Citation2017; Boyce et al., Citation2018). Higher education, being employed, and having a higher income were factors positively associated with greater life satisfaction during a financial crisis (Boyce et al., Citation2018), but factors influencing perceived life satisfaction during or after periods of financial crises may change based on the investigated country. In two multi-country studies, lower life satisfaction was related to poor health in Ireland, to lack of political trust in Greece, and to unemployment status in Portugal, Spain (Halvorsen, Citation2016), and the United Kingdom (Mertens & Beblo, Citation2016).

Studies exploring other aspects of well-being during financial crises reported lower positive affect and increased stress during the crisis (Deaton, Citation2012; Jenkins et al., Citation2023). Higher levels of stress were also reported post-crisis in two studies (Hauksdóttir et al., Citation2013; Jenkins et al., Citation2023). Hauksdóttir et al. (Citation2013) found that women showed higher levels of stress than men, especially those who were unemployed, students, from middle income classes, and who had only some education (i.e. middle or high school diploma). Other studies reported that increased workload (Kronenberg & Boehnke, Citation2019) and daily relationship tensions (Jenkins et al., Citation2023) were risk factors for increased stress. In one study, job satisfaction and social support mediated the relationship between stress and self-rated health during the Global Financial Crisis (Sánchez-Recio et al., Citation2021). One study reported worse well-being in groups of 19-year-olds specifically during periods of financial crises, although trends would recover in the years following the crises (Parker et al., Citation2016).

Among other investigated mental health outcomes, sleep difficulties were reported in one study and were associated with specific factors, such as being older, female, and having a lower level of education (Friedman & Thomas, Citation2009). However, few studies have investigated the impact of financial crises on mental health outcomes other than the ones aforementioned. Although some studies included questions related to a variety of mental health variables, these conditions were either grouped as a general mental health variable (phobia, panic; Barr et al., Citation2015), were not included in the statistical analyses (PTSD; McLaughlin et al., Citation2012), or did not reach statistical significance (panic attacks, alcohol use, eating disorders; Gili et al., Citation2013).

Discussion

The current review aimed to explore the impact of national and international financial crises on mental health and well-being outcomes. The available literature is consistent in showing that financial crises affect the psychological health of the general population, with specific subgroups being at greater risk than others.

Although previous reviews have highlighted a lack of longitudinal studies that explore the impact of financial crises on mental health, the current review found a significant number of longitudinal studies that allowed us to better analyse the long-term effects of financial crises on mental health. In terms of geographical representation, although the majority of studies were conducted in Western countries, especially from the European region, a fairly broad range of countries was considered that allowed for a worldwide perspective on the effects of financial crises on mental health outcomes. This also allowed us to identify commonalities in outcomes and risk factors, thus underlining the need for unified, worldwide policy actions to protect individuals’ mental health from the consequences of financial crises, as already stressed by the WHO and the European Psychiatric Association (Martin-Carrasco et al., Citation2016; WHO, Citation2011).

On the other hand, some differences arose from multi-country studies that highlighted the unique impact of cultural, contextual, and systemic realities. For instance, some studies have hypothesised that stronger social support (i.e. having someone to count on when needed), a social net, and the availability of welfare may play a protective role from the adverse consequences of financial crises (Halvorsen, Citation2016; Norström & Grönqvist, Citation2015; Stuckler et al., Citation2011; Wilkinson, Citation2016). This is not surprising considering that social support has been listed as one of the most important predictors of happiness around the world (Helliwell et al., Citation2017). Relatedly, studies reporting unchanged suicide rates during or after financial crises were conducted in countries with stronger welfare systems and social support (Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Citation2020; Merzagora et al., Citation2016). These results suggest the potential mitigating effects of country-specific realities during periods of crises (Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Citation2020; Mattei et al., Citation2014; Merzagora et al., Citation2016) and underline the importance of considering both macro-level (e.g. government debt, welfare system, health system financing structure) and micro-level factors (e.g. family support) when investigating the impact of financial crises on mental health.

Additionally, our results show that some socio-demographic population groups may be at increased risk of poor mental health compared to others. Specifically, unemployment emerged as a significant risk factor for suicide, with manual workers being most at risk. Interestingly, proactive and preventive measures have shown promise in reducing such risk (Kim, Citation2021). The relationship between suicide and age produced contradictory findings across studies, probably due to contextual factors, such as the types of societal groups or country-specific support systems available.

The explored studies have also highlighted the prevalence of mental or psychological conditions during times of financial crisis. Interestingly, one study showed that demand for mental health services appears to decrease, despite a rise in hospitalisation rates and self-harm incidents (Iglesias García et al., Citation2014). This counterintuitive trend may be due to individuals either avoiding or not being able to access services during these periods. Similar to studies on suicide rates, unemployment emerged again as a significant trigger of poor mental health (Urbanos-Garrido & Lopez-Valcarcel, Citation2015), whereas, among those employed, increased workload, workplace harassment, working in the private sector, or having the place of work downsized contributed towards depression, anxiety, and other measures of psychological distress (e.g. Kronenberg & Boehnke, Citation2019). The included studies yielded mixed results regarding the impact of age, education, and marital status on mental health, although this may reflect nuances in individuals’ incomes, access to financial or family support, job difficulties, job security, the quality of primary relationships, and country-specific support services, as partially emphasised by the WHO (WHO, Citation2011).

Interestingly, gender-related differences have highlighted specific impacts on individuals’ mental health and well-being. For instance, despite overall trends, women’s suicide rates have been shown to remain stable or even decrease during periods of financial constraints, which contrasted with an increase observed in men. However, suicide attempts increased across genders, suggesting the possibility that a contributing factor to higher suicide rates may be due to a greater likelihood of “successful” attempts. This hypothesis aligns with previous findings of men engaging in more violent methods when attempting suicides (Cibis et al., Citation2012). Nonetheless, protective factors such as having social support, higher education or income, or living in countries with better welfare systems emerged as critical elements in mitigating the adverse effects of financial crises on mental well-being.

In contrast to findings related to suicide, women were at an overall greater risk of poor mental health outcomes compared to men. It is therefore likely that gender plays a significant role in the context of increased mental health concerns during financial crises, whereby financial crises can exacerbate existing gender inequalities and create new challenges that disproportionately affect women and men differently. Authors that observed a greater impact of unemployment on men than women hypothesised that such differences may be related to the country’s imposed social role of men as the main household providers (Bartoll et al., Citation2014), thus underlining the influence of cultural factors. This phenomenon has been explained in research by the typically assumed role of men as “breadwinners”, as well as the pressures inherent to this role (Córdoba-Doña et al., Citation2014). In this sense, men who have traditionally served as primary “breadwinners” may experience increased stress and feelings of inadequacy if they lose their jobs or face reduced income during a financial crisis. This shift in gender roles can challenge their sense of identity and self-worth, in turn contributing to reduced mental health (Seedat et al., Citation2009). On the other hand, women, in general, tend to take on a significant portion of caregiving responsibilities for children, the elderly, and family members with disabilities (Revenson et al., Citation2016). During a financial crisis, the increased caregiving burden can lead to exhaustion and emotional strain, impacting their mental health. This may be further exacerbated for women who are the sole caregivers and providers, such as single mothers, as the combination of caregiving responsibilities and part-time or full-time employment can lead to high levels of stress and mental health concerns (Borrell et al., Citation2004).

Implications and recommendations

Overall, the findings of the current review highlight that financial crises significantly affect the psychological health of the general population, with certain subgroups facing higher risks. Based on the findings of this review, we developed a set of comprehensive recommendations aimed at effectively supporting individuals’ mental health during the challenging periods of financial crises (see ). Proactive policy actions are imperative to support the mental health of the general population, and the included recommendations encompass a range of suggested strategies.

Figure 2. ASPIRE: Principles and stakeholder actions to prevent adverse consequences of financial crises on mental health and well-being outcomes.

First, the allocation of government resources to provide psychological and psychiatric support to those struggling with the psychological burden of financial crises is an essential step in promoting resilience and well-being in periods of crises. Second, ensuring that sufficient funds are directed towards reinforcing healthcare systems, particularly mental health services, will allow individuals to receive the support needed during times of crises. Third, a coordinated effort to raise awareness about the detrimental consequences of financial crises on individuals’ mental health, such as education campaigns, is essential to empower individuals to recognise potential psychological symptoms and seek help or change their thoughts/behaviours. Moreover, it is crucial to provide special resources and support to those groups that are inherently more vulnerable in times of financial adversity and groups that may have unique support needs. Finally, it is important to bear in mind the unique contexts and needs of each country. This includes, for instance, recognising variations in financial structures within healthcare systems (Vigo et al., Citation2019), which may significantly influence individuals’ access to mental health services during periods of financial crisis.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Some limitations of the current study are highlighted below. First, the majority of studies conducted in the last three years have been excluded due to the inclusion of the COVID-19 pandemic as the primary reason of the financial crisis. This decision was taken because: (1) COVID-19 is not a financial crisis per se and is likely to have unique effects on mental health and well-being outcomes (e.g. stress, anxiety, depression); (2) the COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing and its financial impact differs greatly between countries and socio-economic groups; and (3) given that more than 100 papers were found specifically exploring the impact of COVID-19-related financial difficulties on mental health outcomes, we believe that the COVID-19 determinant may have biased the remaining findings, which considered financial crises as main or primary determinants of mental health outcomes (n = 98).

Previous reviews have demonstrated a negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals’ mental health and well-being outcomes (Gibson et al., Citation2021; Panchal et al., Citation2023; Schneider et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Existing evidence, primarily from cross-sectional studies, indicates that the pandemic is associated with increases in stress, anxiety, and depression, and a reduction in overall mood and psychological well-being. This is in part due to individuals’ concerns about the economic consequences of the pandemic, particularly among individuals living on lower income brackets (Kämpfen et al., Citation2020; Yang & Ma, Citation2021). However, findings regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on financial markets (Zhang et al., Citation2020) and individual mental health are still mixed, given countries’ varied responses to the pandemic and the adoption of protective measures, such as enforced lockdowns (Desson et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2020). As such, longitudinal research is urgently required to assess the full impact of the ongoing pandemic on financial difficulties, and the subsequent effects on mental health and well-being outcomes.

Second, most studies looked at suicide rates and few other mental health outcomes were considered. However, when excluding studies investigating suicide rates, the variability of research on the association between mental health outcomes and financial crises remains extremely limited, as the majority of studies tend to focus on depression and depressive symptoms exclusively. Although few studies have explored other variables (e.g. anxiety, stress, sleep, eating disorders, general well-being, life satisfaction), evidence is too limited to draw strong conclusions and may therefore limit the generalisability of the current results. Furthermore, these variables have often been investigated together as a general mental health variable, rendering it difficult to highlight the unique effect of each psychological and mental health condition. Other than utilising specific tools to explore the unique contribution of specific mental health outcomes (e.g. anxiety questionnaires), future research may consider extending the already existing literature, and exploring those mental health outcomes that may be potentially exacerbated in periods of financial crises. For instance, specific subgroups, such as employed or highly educated individuals, may experience increased rates of burnout during or after a period of financial crisis, due to work-related or societal expectations. Financial hardship may also cause reduced access to medications or ad-hoc treatments for individuals who require long-term therapy (e.g. individuals with long-lasting psychiatric conditions). Experiences of trauma and physical or psychological abuse may also be exacerbated in periods of financial crises, although no data is to date available to confirm this.

Moreover, the impact of certain demographic variables on the relationship between financial crises and mental health is still unclear. A major gap in the existing literature, for example, is that epidemiological, nation-wide studies, especially those from ethnically diversified countries, have to date failed to investigate the role of ethnicity during periods of financial crises, or at least to include ethnicity among the commonly described socio-demographic variables. Similarly, to the best of our knowledge, no research has been conducted investigating the impact of financial crises on vulnerable populations (e.g. minorities, individuals with chronic health conditions). It has been shown that in situations of global crises, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, vulnerable and marginalised groups are impacted the hardest (Gibson et al., Citation2021). Given that these groups are also affected the most by austerity measures (WHO, Citation2011), it may be that their mental health is especially at risk during and following periods of financial crises. This should be explored in future research.

Finally, it would be pertinent to explore the influence of the availability of healthcare services during times of financial crises, especially in cases of reduced resources or budget cuts, which may create challenges in accessing and delivering timely mental health support. None of the studies included in the current review considered this factor in their analyses. Therefore, future research should explore this variable in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics impacting mental health during financial crises.

Conclusions

This review confirms the undeniable impact of national and international financial crises on population-level mental health and well-being, while also underlining the countless nuances influencing this impact, including cultural, contextual, and systematic factors. Furthermore, the longitudinal studies included in our review show the long-term repercussions of financial crises and highlight the crucial and urgent need for social support and welfare systems to safeguard the mental health of individuals. Finally, although additional research is needed for a more comprehensive view, several vulnerable population groups were identified to be at greater risk of mental health consequences due to financial crises, including unemployed individuals, those with lower income or education, and individuals with a history of mental health conditions. By addressing the distinct needs of various groups and populations, policymakers have the instruments to mitigate the mental health impact of financial crises and build a more resilient society.

PRISMA/PROSPERO

This systematic review was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) and was preregistered on PROSPERO (ref no. CRD42022372137) prior to commencement (16 November 2022).

Authors contributions

Deborah Talamonti: Writing – original draft, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualisation. Jekaterina Schneider: Writing – original draft, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualisation. Benjamin Gibson: Writing – review & editing, formal analysis, methodology. Mark Forshaw: Writing – review & editing, supervision, validation, conceptualisation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachel Arulanantham and Dr. Steve Nolan, who provided feedback on our original search strategy and helped refine the search terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AlNemer, H. A. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic and global food security: a bibliometric analysis and future research direction. International Journal of Social Economics, 50(5), 709–724. doi:10.1108/IJSE-08-2022-0532.

- Alvarez-Galvez, J., Salinas-Perez, J. A., Rodero-Cosano, M. L., & Salvador-Carulla, L. (2017). Methodological barriers to studying the association between the economic crisis and suicide in Spain. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 694. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4702-0.

- Alvarez-Galvez, J., Suarez-Lledo, V., Salvador-Carulla, L., & Almenara-Barrios, J. (2021). Structural determinants of suicide during the global financial crisis in Spain: Integrating explanations to understand a complex public health problem. PLOS One, 16(3), e0247759. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247759.

- Antonakakis, N., & Collins, A. (2014). The impact of fiscal austerity on suicide: On the empirics of a modern Greek tragedy. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 112, 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.019.

- Ásgeirsdóttir, H. G., Valdimarsdóttir, U. A., Nyberg, U., Lund, S. H., Tomasson, G., Orsteinsdóttir, R. K., Sgeirsdóttir, T. L., & Hauksdóttir, A. (2020). Suicide rates in Iceland before and after the 2008 global recession: A nationwide population-based study. European Journal of Public Health, 30(6), 1102–1108. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa121.

- Astell-Burt, T., & Feng, X. (2013). Health and the 2008 economic recession: Evidence from the United Kingdom. PLOS One, 8(2), e56674. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056674.

- Avčin, B. A., Kučina, A. U., Šarotar, B. N., Radovanović, M., & Plesničar, B. K. (2011). The present global financial and economic crisis poses an additional risk factor for mental health problems on the employees. Psychiatria Danubina, 23(Suppl 1), 142–148.

- Bacigalupe, A., Esnaola, S., & Martín, U. (2016). The impact of the great recession on mental health and its inequalities: The case of a Southern European region, 1997-2013. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 17. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0283-7.

- Barr, B., Taylor-Robinson, D., Scott-Samuel, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 345, e5142. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5142 22893569

- Barr, B., Kinderman, P., & Whitehead, M. (2015). Trends in mental health inequalities in England during a period of recession, austerity and welfare reform 2004 to 2013. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 324–331. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.009.

- Bartoll, X., Palència, L., Malmusi, D., Suhrcke, M., & Borrell, C. (2014). The evolution of mental health in Spain during the economic crisis. European Journal of Public Health, 24(3), 415–418. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt208.

- Baumbach, A., & Gulis, G. (2014). Impact of financial crisis on selected health outcomes in Europe. European Journal of Public Health, 24(3), 399–403. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku042.

- Bayliss, D., Olsen, W., & Walthery, P. (2017). Well-being during recession in the UK. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12(2), 369–387. doi:10.1007/s11482-016-9465-8.

- Bøe, T., Sivertsen, B., Heiervang, E., Goodman, R., Lundervold, A. J., & Hysing, M. (2014). Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The role of parental emotional well-being and parenting practices. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 705–715. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9818-9.

- Bonnie Lee, C., Liao, C. M., & Lin, C. M. (2017). The impacts of the global financial crisis on hospitalizations due to depressive illnesses in Taiwan: A prospective nationwide population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221(5), 65–71. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.028.

- Borrell, C., Muntaner, C., Benach, J., & Artazcoz, L. (2004). Social class and self-reported health status among men and women: What is the role of work organisation, household material standards and household labour? Social Science & Medicine, 58(10), 1869–1887. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00408-8.

- Boyce, C. J., Delaney, L., & Wood, A. M. (2018). The great recession and subjective well-being: How did the life satisfaction of people living in the United Kingdom change following the financial crisis? PLOS One, 13(8), e0201215. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201215.

- Branas, C. C., Kastanaki, A. E., Michalodimitrakis, M., Tzougas, J., Kranioti, E. F., Theodorakis, P. N., Carr, B. G., & Wiebe, D. J. (2015). The impact of economic austerity and prosperity events on suicide in Greece: A 30-year interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ Open, 5(1), e005619–e005619. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005619.

- Buffel, V., Van de Velde, S., & Bracke, P. (2015). The mental health consequences of the economic crisis in Europe among the employed, the unemployed, and the non-employed. Social Science Research, 54, 263–288. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.08.003.

- Burgard, S. A., & Hawkins, J. M. (2014). Race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and foregone health care in the United States in the 2007-2009 recession. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e134–140. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301512.

- Burns, P., & Gimpel, J. G. (2000). Economic insecurity, prejudicial stereotypes, and public opinion on immigration policy. Political Science Quarterly, 115(2), 201–225. doi:10.2307/2657900.

- Chan, C. H., Caine, E. D., You, S., Fu, K. W., Chang, S. S., & Yip, P. S. F. (2014). Suicide rates among working-age adults in South Korea before and after the 2008 economic crisis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(3), 246–252. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-202759.

- Chang, S. S., Gunnell, D., Sterne, J. A. C., Lu, T. H., & Cheng, A. T. A. (2009). Was the economic crisis 1997-1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Social Science & Medicine, 68(7), 1322–1331. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.010.

- Chang, S. S., Stuckler, D., Yip, P., & Gunnell, D. (2013). Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: Time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ, 347(7925), f5239. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5239.

- Christodoulou, N. G., & Christodoulou, G. N. (2013). Financial crises: Impact on mental health and suggested responses. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(5), 279–284. doi:10.1159/000351268.

- Cibis, A., Mergl, R., Bramesfeld, A., Althaus, D., Niklewski, G., Schmidtke, A., & Hegerl, U. (2012). Preference of lethal methods is not the only cause for higher suicide rates in males. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(1-2), 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.032.

- Coope, C., Gunnell, D., Hollingworth, W., Hawton, K., Kapur, N., Fearn, V., Wells, C., & Metcalfe, C. (2014). Suicide and the 2008 economic recession: Who is most at risk? Trends in suicide rates in England and Wales 2001-2011. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.024.

- Corcoran, P., Griffin, E., Arensman, E., Fitzgerald, A. P., & Perry, I. J. (2015). Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: An interrupted time series analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(3), 969–977. doi:10.1093/ije/dyv058.

- Córdoba-Doña, J. A., San Sebastián, M., Escolar-Pujolar, A., Martínez-Faure, J. E., & Gustafsson, P. E. (2014). Economic crisis and suicidal behaviour: The role of unemployment, sex and age in Andalusia, Southern Spain. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 55. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-13-55.

- De Bruin, W. B. (2021). Age differences in COVID-19 risk perceptions and mental health: Evidence from a National U.S. Survey conducted in March 2020. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 76(2), E24–E29. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa074.

- De Vogli, R., Marmot, M., & Stuckler, D. (2013). Excess suicides and attempted suicides in Italy attributable to the great recession. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(4), 378–379. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201607.

- Deaton, A. (2012). The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(1), 1–26. doi:10.1093/oep/gpr051.

- Desson, Z., Weller, E., McMeekin, P., & Ammi, M. (2020). An analysis of the policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in France, Belgium, and Canada. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 430–446. doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.09.002.

- Drydakis, N. (2015). The effect of unemployment on self-reported health and mental health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A longitudinal study before and during the financial crisis. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.025.

- Economou, M., Angelopoulos, E., Peppou, L. E., Souliotis, K., & Stefanis, C. (2016a). Major depression amid financial crisis in Greece: Will unemployment narrow existing gender differences in the prevalence of the disorder in Greece? Psychiatry Research, 242, 260–261. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.041.

- Economou, M., Angelopoulos, E., Peppou, L. E., Souliotis, K., & Stefanis, C. (2016b). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in Greece during the economic crisis: An update. World Psychiatry, 15(1), 83–84. doi:10.1002/wps.20296.

- Economou, M., Madianos, M., Peppou, L. E., Patelakis, A., & Stefanis, C. N. (2013). Major depression in the Era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(3), 308–314. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.008.

- Economou, M., Madianos, M., Theleritis, C., Peppou, L. E., & Stefanis, C. N. (2011). Increased suicidality amid economic crisis in Greece. Lancet, 378(9801), 1459–1460. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61639-5.

- Evans-Lacko, S., Knapp, M., McCrone, P., Thornicroft, G., & Mojtabai, R. (2013). The mental health consequences of the recession: Economic hardship and employment of people with mental health problems in 27 European Countries. PLOS One, 8(7), e69792. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069792.

- Frasquilho, D., Matos, M. G., Salonna, F., Guerreiro, D., Storti, C. C., Gaspar, T., & Caldas-De-Almeida, J. M. (2015). Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: A systematic literature review Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 115 doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2720-y.

- Friedman, J., & Thomas, D. (2009). Psychological health before, during, and after an economic crisis: Results from Indonesia, 1993-2000. The World Bank Economic Review, 23(1), 57–76. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn013.

- Garcy, A. M., & Vågerö, D. (2012). The length of unemployment predicts mortality, differently in men and women, and by cause of death: a six year mortality follow-up of the Swedish 1992-1996 recession. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(12), 1911–1920. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.034 22465382

- Iglesias García, C., Martinez, P. S., González, M. P. G. P., GarcÍa, M. B., TreviÑo, L. J., Lasheras, F. S., & Bobes, J. (2014). Effects of the economic crisis on demand due to mental disorders in Asturias: Data from the Asturias Cumulative Psychiatric Case Register (2000-2010). Actas Espanolas De Psiquiatria, 42(3), 108–115.

- Iglesias-García, C., Sáiz, P. A., Burón, P., Sánchez-Lasheras, F., Jiménez-Treviño, L., Fernández-Artamendi, S.,… & Bobes, J. ( 2017). Suicide, unemployment, and economic recession in Spain. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition), 10(2), 70-77. doi:10.1016/j.rpsmen.2017.03.001.

- Isabel, R.-P., Miguel, R.-B., Antonio, R.-G., & Oscar, M.-G. (2017). Economic crisis and suicides in Spain. Socio-demographic and regional variability. The European Journal of Health Economics : HEPAC : health Economics in Prevention and Care, 18(3), 313–320. doi:10.1007/s10198-016-0774-5 26935181.

- Garcy, A. M., & Vagerö, D. (2013). Unemployment and suicide during and after a deep recession: A longitudinal study of 3.4 million swedish men and women. American Journal of Public Health, 103(6), 1031–1038. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301210.

- Gibson, B., Schneider, J., Talamonti, D., & Forshaw, M. (2021). The impact of inequality on mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 62(1), 101–126. doi:10.1037/cap0000272.

- Gili, M., Roca, M., Basu, S., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2013). The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: Evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. European Journal of Public Health, 23(1), 103–108. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks035.

- Hagquist, C. (1998). Youth unemployment, economic deprivation and suicide. Scandinavian Journal of Social Welfare, 7(4), 330–339. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.1998.tb00253.x.

- Halvorsen, K. (2016). Economic, financial, and political crisis and well-being in the PIGS-countries. SAGE Open, 6(4), 215824401667519. doi:10.1177/2158244016675198.

- Harper, S., & Bruckner, T. A. (2017). Did the Great Recession increase suicides in the USA? Evidence from an interrupted time-series analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 27(7), 409.e6–414.e6. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.05.017.

- Hauksdóttir, A., McClure, C., Jonsson, S. H., Ólafsson, Ö., & Valdimarsdóttir, U. A. (2013). Increased stress among women following an economic collapse-a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 177(9), 979–988. doi:10.1093/aje/kws347.

- Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. D. (2017). World happiness report 2017. https://worldhappiness.report/

- Hintikka, J., Saarinen, P. I., & Viinamäki, H. (1999). Suicide mortality in Finland during an economic cycle, 1985–1995. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 85–88. doi:10.1177/14034948990270020601.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Version 2018. User Guide (pp. 1–11). McGill University.

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. doi:10.1177/001316446002000104.

- Jenkins, A. I. C., Le, Y., Surachman, A., Almeida, D. M., & Fredman, S. J. (2023). Associations among financial well-being, daily relationship tension, and daily affect in two adult cohorts separated by the great recession. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(4), 1103–1125. doi:10.1177/02654075221105611.

- Kam, S., Hwang, B. J., & Parker, E. R. (2023). The impact of climate change on atopic dermatitis and mental health comorbidities: A review of the literature and examination of intersectionality. International Journal of Dermatology, 62(4), 449–458. doi:10.1111/ijd.16557.

- Kämpfen, F., Kohler, I. V., Ciancio, A., de Bruin, W. B., Maurer, J., & Kohler, H. P. (2020). Predictors of mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the US: Role of economic concerns, health worries and social distancing. PLOS One, 15(11), e0241895. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241895.

- Katikireddi, S. V., Niedzwiedz, C. L., & Popham, F. (2012). Trends in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession: A repeat cross-sectional analysis of the 1991-2010 Health Surveys of England. BMJ Open, 2(5), e001790. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001790.

- Khang, Y. H., Lynch, J. W., & Kaplan, G. A. (2005). Impact of economic crisis on cause-specific mortality in South Korea. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(6), 1291–1301. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi224.

- Kim, A. M. (2021). Suicide rates by occupation in Korea, 1993–2017: the impacts of financial crisis and suicide policy. Psychiatry Research, 298, 113787. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113787.

- Kim, H., Young, J. S., Jee, J. Y., Woo, J. C., & Chung, M. N. (2004). Changes in mortality after the recent economic crisis in South Korea. Annals of Epidemiology, 14(6), 442–446. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.018.

- Knapp, M., & Wong, G. (2020). Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry, 19(1), 3–14. doi:10.1002/wps.20692.

- Konieczna, A., Jakobsen, S. G., Larsen, C. P., & Christiansen, E. (2022). Recession and risk of suicide in Denmark during the 2009 global financial crisis: an ecological register-based study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(5), 584–592. doi:10.1177/14034948211013270.

- Konstantakopoulos, G., Pikouli, K., Ploumpidis, D., Bougonikolou, E., Kouyanou, K., Nystazaki, M., & Economou, M. (2019). The impact of unemployment on mental health examined in a community mental health unit during the recent financial crisis in Greece. Psychiatrike = Psychiatriki, 30(4), 281–290. doi:10.22365/jpsych.2019.304.281.

- Kronenberg, C., & Boehnke, J. R. (2019). How did the 2008-11 financial crisis affect work-related common mental distress? Evidence from 393 workplaces in Great Britain. Economics and Human Biology, 33, 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2019.02.008.

- Kubrin, C. E., Bartos, B. J., & McCleary, R. (2022). The debt crisis, austerity measures, and suicide in Greece. Social Science Quarterly, 103(1), 120–140. doi:10.1111/ssqu.13118.

- Laliotis, I., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Stavropoulou, C. (2016). Total and cause-specific mortality before and after the onset of the Greek economic crisis: an interrupted time-series analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 1(2), e56–e65. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(16)30018-4.

- Lee, S., Guo, W. J., Tsang, A., Mak, A. D. P., Wu, J., Ng, K. L., & Kwok, K. (2010). Evidence for the 2008 economic crisis exacerbating depression in Hong Kong. Journal of Affective Disorders, 126(1-2), 125–133. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.007.

- Lindström, M., & Giordano, G. N. (2016). The 2008 financial crisis: Changes in social capital and its association with psychological wellbeing in the United Kingdom- A panel study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 153, 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.008 26889949.

- Liu, H., Manzoor, A., Wang, C., Zhang, L., & Manzoor, Z. (2020). The COVID-19 outbreak and affected countries stock markets response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 1–19. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082800.

- López-Contreras, N., Rodríguez-Sanz, M., Novoa, A., Borrell, C., Medallo Muñiz, J., & Gotsens, M. (2019). Socioeconomic inequalities in suicide mortality in Barcelona during the economic crisis (2006–2016): A time trend study. BMJ Open, 9(8), e028267. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028267.

- Lopez Bernal, J. A., Gasparrini, A., Artundo, C. M., & McKee, M. (2013). The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suicides in Spain: An interrupted time-series analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 23(5), 732–736. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt083.

- Madianos, M., Economou, M., Alexiou, T., & Stefanis, C. (2011). Depression and economic hardship across Greece in 2008 and 2009: Two cross-sectional surveys nationwide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(10), 943–952. doi:10.1007/s00127-010-0265-4.

- Marazziti, D., Avella, M. T., Mucci, N., Della Vecchia, A., Ivaldi, T., Palermo, S., & Mucci, F. (2021). Impact of economic crisis on mental health: A 10-year challenge. CNS Spectrums, 26(1), 7–13. doi:10.1017/S1092852920000140.

- Martin-Carrasco, M., Evans-Lacko, S., Dom, G., Christodoulou, N. G., Samochowiec, J., González-Fraile, E., Bienkowski, P., Gómez-Beneyto, M., Dos Santos, M. J. H., & Wasserman, D. (2016). EPA guidance on mental health and economic crises in Europe. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 266(2), 89–124. doi:10.1007/s00406-016-0681-x.

- Mattei, G., Ferrari, S., Pingani, L., & Rigatelli, M. (2014). Short-term effects of the 2008 Great Recession on the health of the Italian population: An ecological study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(6), 851–858. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0818-z.

- McInerney, M., Mellor, J. M., & Nicholas, M. H. (2013). Recession Depression: Mental Health Effects of the 2008 Stock Market Crash. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1090–1104. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.09.002.

- McLaughlin, K. A., Nandi, A., Keyes, K. M., Uddin, M., Aiello, A. E., Galea, S., & Koenen, K. C. (2012). Home foreclosure and risk of psychiatric morbidity during the recent financial crisis. Psychological Medicine, 42(7), 1441–1448. doi:10.1017/S0033291711002613.

- Mertens, A., & Beblo, M. (2016). Self-reported satisfaction and the economic crisis of 2007–2010: or how people in the UK and Germany perceive a severe cyclical downturn. Social Indicators Research, 125(2), 537–565. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0854-9.

- Merzagora, I., Mugellini, G., Amadasi, A., & Travaini, G. (2016). Suicide risk and the economic crisis: An exploratory analysis of the case of Milan. PLOS One, 11(12), e0166244. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166244.

- Milner, A. J., Niven, H., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2015). Occupational class differences in suicide: Evidence of changes over time and during the global financial crisis in Australia. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 223. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0608-5.

- Milner, A., Morrell, S., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2014). Economically inactive, unemployed and employed suicides in australia by age and sex over a 10-year period: What was the impact of the 2007 economic recession? International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(5), 1500–1507. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu148.

- Mohseni-Cheraghlou, A. (2016). The aftermath of financial crises: A look on human and social wellbeing. World Development, 87, 88–106. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.06.001.

- Mylona, K., Tsiantou, V., Zavras, D., Pavi, E., & Kyriopoulos, J. (2014). Determinants of self-reported frequency ofdepressive symptoms in Greece during economiccrisis. Public Health, 128(8), 752–754. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2014.05.009.

- Neocleous, G., & Apostolou, M. (2021). Financial recession as a predictor of stress in human service professionals: The case of Cyprus. International Social Work, 64(1), 74–84. doi:10.1177/0020872818797998.

- Neumayer, E. (2004). Recessions lower (some) mortality rates: Evidence from Germany. Social Science & Medicine, 58(6), 1037–1047. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00276-4.

- Norström, T., & Grönqvist, H. (2015). The great recession, unemployment and suicide. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(2), 110–116. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204602.

- Ostamo, A., & Lönnqvist, J. (2001). Attempted suicide rates and trends during a period of severe economic recession in Helsinki, 1989–1997. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36(7), 354–360. doi:10.1007/s001270170041.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

- Paleologou, M. P., Anagnostopoulos, D. C., Lazaratou, H., Economou, M., Peppou, L. E., & Malliori, M. (2018). Adolescents’ mental health during the financial crisis in Greece: The first epidemiological data. Psychiatrike = Psychiatriki, 29(3), 271–274. doi:10.22365/jpsych.2018.293.271.

- Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., Moreno, C., Parellada, M., Arango, C., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(7), 1151–1177. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w.

- Parker, P. D., Jerrim, J., & Anders, J. (2016). What effect did the global financial crisis have upon youth wellbeing? Evidence from four Australian cohorts. Developmental Psychology, 52(4), 640–651. doi:10.1037/dev0000092.

- Pfoertner, T. K., Rathmann, K., Elgar, F. J., De Looze, M., Hofmann, F., Ottova-Jordan, V., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Bosakova, L., Currie, C., & Richter, M. (2014). Adolescents’ psychological health complaints and the economic recession in late 2007: A multilevel study in 31 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 24(6), 961–967. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku056.

- Phillips, M. R., Liu, H., & Zhang, Y. (1999). Suicide and social change in China. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 23(1), 25–50. doi:10.1023/A:1005462530658.

- Pompili, M., Vichi, M., Innamorati, M., Lester, D., Yang, B., De Leo, D., & Girardi, P. (2014). Suicide in Italy during a time of economic recession: Some recent data related to age and gender based on a nationwide register study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(4), 361–367. doi:10.1111/hsc.12086.

- Rachiotis, G., Stuckler, D., McKee, M., & Hadjichristodoulou, C. (2015). What has happened to suicides during the Greek economic crisis? Findings from an ecological study of suicides and their determinants (2003-2012). BMJ Open, 5(3), e007295. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007295.

- Rahmqvist, M., & Carstensen, J. (1998). Trend of psychological distress in a Swedish population from 1989 to 1995. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 26(3), 214–222. doi:10.1177/14034948980260031201.