Abstract

Background

The long-term mental and physical health implications of childhood interpersonal trauma on adult survivors is immense, however, there is a lack of available trauma-focused treatment services that are widely accessible. This study, utilizing a user-centered design process, sought feedback on the initial design and development of a novel, self-paced psychoeducation and skills-based treatment intervention for this population.

Aims

To explore the views and perspectives of adult survivors of childhood interpersonal trauma on the first two modules of an asynchronous trauma-focused treatment program.

Methods

Fourteen participants from our outpatient hospital service who completed the modules consented to provide feedback on their user experience. A thematic analysis of the three focus groups was conducted.

Results

Four major themes emerged from the focus groups: (1) technology utilization, (2) module content, (3) asynchronous delivery, and (4) opportunity for interactivity. Participants noted the convenience of the platform and the use of multimedia content to increase engagement and did not find the modules to be emotionally overwhelming.

Conclusions

Our research findings suggest that an asynchronous virtual intervention for childhood interpersonal trauma survivors may be a safe and acceptable way to provide a stabilization-focused intervention on a wider scale.

Introduction

Childhood interpersonal trauma (CIT) is a global public health concern (Maercker et al., Citation2022; Saunders & Adams, Citation2014). Studies have reported prevalence rates for different types of childhood trauma including physical abuse (22–38%); sexual abuse (4–12%), and emotional abuse or neglect (40–62%) (Cotter, Citation2021; McTavish et al., Citation2022; Pace et al., Citation2022). CIT has been identified as a major contributing factor to the development of PTSD (Lewis et al., Citation2019; McLaughlin et al., Citation2013). Individuals who have experienced interpersonal trauma in childhood are at increased risk for mental and physical health issues, including serious mental illness, depression, anxiety, emotion dysregulation, substance abuse, chronic physical conditions, and revictimization (Afifi et al., Citation2014; Atwoli et al., Citation2016; Cloitre et al., Citation2009; Hughes et al., Citation2017; Maercker et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, the economic burden of the impact of CIT is immense; a 2003 report to the Law Commission of Canada estimated the annual socioeconomic cost of child abuse to be over 15 billion dollars, in terms of health care, social services, education, judicial system, employment, and personal costs (Bellis et al., Citation2019; Bowlus et al., Citation2003; Graziani et al., Citation2022). Thus, it is imperative to develop innovative, scalable, treatment interventions for the effects of CIT that meet the needs of this diverse and complex population.

There is a significant gap in terms of the high prevalence of CIT, and the lack of access to treatment for PTSD and other trauma-related co-morbid symptoms experienced by many survivors (Alcalá et al., Citation2018; Damian et al., Citation2018, Kohn et al.,2004). In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the increased need for mental health services, evidenced by even longer wait times for in-person or synchronous services (Brooks et al., Citation2020; Moreno et al., Citation2020; Rauschenberg et al., Citation2021; Whaibeh et al., Citation2020). Synchronous services in healthcare include visits delivered “live” with real-time interactions between the service user and the provider, for example, through a video or phone visit, Virtual or web-based interventions are gaining traction, including asynchronous, and hybrid options that can improve access to care more efficiently than in-person services (Andersson et al., Citation2019; Deady et al., Citation2017; Gilmore et al., Citation2017, Olthuis et al., Citation2016; Sloan et al., Citation2011; Torous & Keshavan, Citation2020; Zhou et al., Citation2020). Asynchronous services lack a “real-time” interaction and includes things like secure messaging, mobile health devices, self-paced virtual learning, and online portals. However, further research is needed to understand how to develop inclusive, accessible, and effective virtual services (Hollis et al., Citation2017, Kerst et al., Citation2020; Kruse et al., Citation2018, Patel et al., Citation2020, Sunjaya et al., Citation2020; Turgoose et al., Citation2018). Importantly, offering asynchronous or hybrid treatment options may increase access to treatment for those from marginalized or underrepresented groups who may hesitate to access services in-person or synchronous virtual formats (Berger, Citation2017; Fortney et al., Citation2015; Martínez et al., Citation2018; Mongelli et al., Citation2020; Nickerson et al., Citation2020; Robards et al., Citation2018; Sandre & Newbold Citation2016).

Recently, several studies have explored user-centred design approaches for the development of virtual interventions in mental health (Altman et al., Citation2018; Gould et al., Citation2020; Vial et al., Citation2022). This approach involves taking into consideration the user’s needs and preferences when designing, developing, and implementing a service or technology (Ferrucci et al., Citation2021; Göttgens & Oertelt-Prigione, Citation2021). Moreover, it has been found to be a cost-effective means of creating scalable interventions (Liu et al., Citation2022). One of the key principles of user-centred design is prioritizing simplicity for users (Lyon & Koerner, Citation2016), as well as making sure the service fits into the context of the user’s life (Mohr et al., Citation2018). Applying this approach to the development of an asynchronous virtual program for mental health can help to ensure its usability and usefulness, by tailoring it to the needs and preferences of stakeholders.

Despite the potential of virtual interventions to improve access to treatment for PTSD and other trauma-related symptoms the acceptability and efficacy of such interventions in this population has not been widely studied (Bröcker et al., Citation2022; Erbe et al., Citation2017; van Lotringen et al., Citation2021). To evaluate the impact of virtual interventions in this population, additional research is needed to assess the acceptability, safety, and effectiveness of these interventions and to inform clinical practice (Bisson et al., Citation2022). Currently, exposure-based interventions are the first-line treatment for the sequelae of PTSD, however, dropout rates in evidence-based PTSD interventions can be a concern (Alpert et al., Citation2020; Schrader & Ross, Citation2021; Simon et al., Citation2019). Other evidence-based approaches for the treatment of trauma-related difficulties, including PTSD, include a staged approach that begins with psychoeducation and skills-based interventions that focus on helping survivors to better regulate emotions (Cloitre et al., Citation2010, Citation2019; Coventry et al., 2020; Lewis et al., Citation2020; Melton et al., Citation2020; ISTSS, ISSTD).

At Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, the Trauma Therapy Program (TTP) offers a foundational group called the “Resourced and Resilient Group” (R&R) that is grounded in the staged approach. This psychoeducation and skills-based group, initially developed in 2004 by a multidisciplinary team of therapists, is a standardized, structured, 8-week group intervention that has been offered to thousands of adults. It combines evidence-based therapy approaches such as mindfulness-based interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy, somatic-oriented psychotherapy, and communication skills training. The R&R program is offered in person and virtually, using the Zoom video platform during the COVID pandemic. Unfortunately, the demand for trauma therapy services far exceeds the available resources, and the TTP has an extensive waitlist of adults seeking treatment.

In response to the high demand for services, this study aims to develop an innovative intervention called electronic Resourced & Resilient (eR&R) to help more people quickly access foundational level care, while also using fewer therapist resources. This study’s objective was to look at acceptability of this intervention, through understanding participants’ perceptions and experiences of the first two eR&R modules, particularly regarding the asynchronous nature of the intervention, and the technological aspects. We believe that involving service users at the earliest stages of design and development will allow us to build an asynchronous treatment intervention that meets the needs and preferences of this complex population. This eR&R program has the potential to be a scalable, accessible intervention for the treatment of the impact of CIT, including symptoms related to PTSD, that could greatly enhance access to care.

Methods

Study design

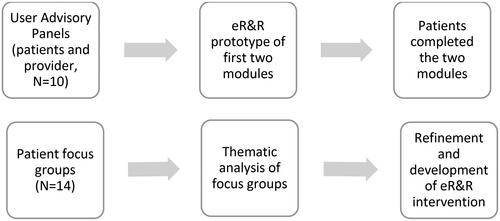

Preliminary steps involved following a user-centered design approach that started with a discussion with service users and healthcare providers via User Advisory Panels that informed the initial design phase (Altman et al., Citation2018; Gould et al., Citation2020; Vial et al., Citation2022). This allowed us to develop the first two multimedia modules of the asynchronous virtual eR&R intervention which allowed participants to experience enough content that they could provide feedback in the focus groups. Creating multimedia content can be resource intensive and we wanted to get initial feedback prior to developing the remaining modules. We conducted focus groups with service users to assess their comfort level with technology, any technological issues, or barriers to accessing the modules, and their experience with the asynchronous delivery aspect and multimedia content. Additionally, we asked for their recommendations for future iterations.

Our user-centered design process followed the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the development of complex interventions, in conjunction with other published guidelines developed to guide the creation of eHealth interventions (Craig et al., 2008; Gaebel et al., Citation2017; Jaspers et al., Citation2004; McGrath et al., Citation2018; Moore et al., Citation2015; Strudwick et al., Citation2020). Our methods included validated User-Centered Design principles such as recruiting potential users, conducting focus groups about user perspectives, engaging in iterative development, and designing in teams (Dopp et al., Citation2019, Ferrucci et al., Citation2021; Göttgens & Oertelt-Prigione, Citation2021). See for a breakdown of our intervention design process.

Participants

Multidisciplinary trauma therapists who conducted R&R groups identified potential focus group participants. Potential participants had completed at least six of eight group sessions of a synchronous R&R group in the Trauma Therapy Program. For the purpose of this study, we wanted to focus on the novel asynchronous delivery platform and multimedia format, so participant familiarity with the R&R content was preferred. All adults accepted into our Trauma Therapy Program have mental health sequelae related to a history of childhood interpersonal trauma, but do not necessarily have a specific psychiatric diagnosis. Common sequelae reported in our clinical program include PTSD symptoms, anxiety and depression, substance use, emotion dysregulation, ADHD, interpersonal difficulties, and psychosocial struggles, A study research assistant explained the study to eligible participants and obtained informed consent.

Consenting participants were provided with access to the eR&R platform and completed the first two (of eight planned) eR&R modules (see for an outline of the module content). Then, focus groups were conducted with participants by a research assistant (AB) and the PI (DCR) following a semi-structured topic guide that was developed in collaboration with co-authors DR and SS [see Appendix A]. The focus groups were conducted in English using Zoom and were audio-recorded. Prior to analysis, the recordings were transcribed and de-identified. The research assistant took additional field notes during the focus groups.

Table 1. eR&R module content outline.

Analysis

Data were analysed thematically using an inductive approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Two researchers (AB, AKT) independently open-coded the transcripts and generated themes and sub-themes from the data using Microsoft Word. The researchers reviewed the themes they generated then developed a singular coding guide based on agreement and reliability of the major areas captured by the themes and subthemes. One of the researchers (AKT) recoded the transcripts using the final coding guide, and two researchers (AKT, AB) summarized the findings under each theme and sub-theme with the assistance of a research student.

Ethics

This initiative was formally reviewed by institutional authorities at Women’s College Hospital and was deemed not to require Research Ethics Board approval (REB #2020-0014-E). All participants gave written informed consent for their data to be used. They received a gift card of 20 CAD.

Results

The eR&R modules were created using the Thinkific Learning Management Platform (Thinkific, n.d.) following approval from the WCH Privacy Department. We developed original videos, animations, quizzes, movement exercises, podcasts and electronic text materials for the first two modules of eR&R. All module content was created through a collaboration involving one of the co-PIs (DCR) and the multidisciplinary trauma therapists in the Trauma Therapy Program at Women’s College Hospital.

We recruited 14 adults enrolled in the Trauma Therapy Program to complete the first two modules and participate in one of three focus groups (n = 5 in two of the groups, n = 4 in one of the groups). The focus groups consisted of 11 women and 3 men. All participants had completed both e-modules and no potential participants who were approached refused to participate or were excluded.

After completing the coding, some themes were specific to the logistics of the Trauma Therapy Program at WCH and less relevant to the perceptions of the asynchronous and technological aspects of the program and were therefore omitted from analysis.

Focus group content analysis revealed four main themes: (1) Technology Utilization, (2) Module Content, (3) Asynchronous Delivery, and (4) Opportunity for Interactivity (). Anonymized data extracts are used in presenting findings ().

Table 2. Coding tree.

Table 3. Major themes from qualitative focus groups and example quotes.

Three Focus Groups with Participants (N = 14)

Technology utilization

Participants commented on their experience with the virtual program and shared specific technological issues they experienced with the program platform. Three participants mentioned having done virtual programs in the past, and most participants were fairly comfortable with technology and had previously used virtual platforms for mental health resources. General technological issues with the virtual program that the team flagged to fix in iterative development are found in the .

Table 4. Examples of technological fixes in iterative development.

Module content

What worked. Participants agreed that the module content was well balanced in terms of information volume and topic complexity. Modules were easy to complete independently. Participants agreed that having the TTP therapists and staff rather than actors made the learning experience more personal and comforting.

“I wondered how it would be to do a course like this online without that support right there of a therapist, and I thought the material that you covered was really appropriate for that. It wasn’t too heavy or things that would likely be triggering.” – Focus Group 1

“it’s all the same content [as synchronous R&R], but it’s broken down in a way that’s more digestible.” – Focus Group #1

Breaks and exercises. Participants agreed that the videos inviting participants to engage in a variety of movement exercises, breathing, meditation, and self-reflective exercises were well-spaced throughout the modules and provided them with more opportunities to reset and reflect before proceeding and to strengthen their mind-body connection.

“I find that stuff really valuable because just personally, I’m not somebody who is super-connected with their body so somebody saying, ‘Hey, give this a shot and see what happens’ [is really valuable].” – Focus Group #2

Multimedia. Most participants agreed that the multimedia format was much more engaging and provided more opportunities to learn through different formats than the regular synchronous R&R groups. They were able to remain focused and absorb more content as they reviewed information at their own pace; and it was less monotonous than reading a handout. Two participants appreciated the option of having transcripts to read alongside the video and audio recordings, as they made the content easier to follow. Several mentioned that they enjoyed the optional, low-stakes multiple-choice question quizzes and appreciated that they were optional as it reduced the pressure to complete it. Participants particularly enjoyed the whiteboard animations and found that the animated videos throughout the modules were helpful in terms of learning as it made the content more visual and engaging.

“I found it’s easier for me to absorb the information through video or podcasts. I’m not very focused when I need to read something, so it’s very helpful for me that I don’t need to read a bunch of long paragraphs or some information.” – Focus Group #3

Recommendations

Participant suggestions ranged from module structure and design to more specific details to further strengthen the virtual program. A challenge identified by participants was that they would have liked more direction on how to utilize the abundance of information from the modules to implement what they learned into their lives (see ).

Table 5. Participant recommendations for module content.

Asynchronous delivery

Self-paced

A major benefit of the virtual modules was participants’ ability to complete them at their own pace. Participants observed that it is easier for them to focus as they could take breaks as needed, and they could pause or rewind to ensure that the content was absorbed, particularly for triggering and sensitive topics. Furthermore, the virtual platform was convenient; it reduced travel time and expense, and participants could access it from safe spaces. Several participants also appreciated the discussion in the introduction on the importance of pacing themselves through the modules as it served as a helpful reminder and promoted more participant-centered values.

“[…] [W]hen you’re going through trauma-related work, sometimes it’s necessary to take a break […] To me, [that was] one of the benefits [of the modules]. So, right away, I was given this overall sense of no pressure, no rush, this is for you, so it was very welcoming.” – Focus Group #1

“I prefer (virtual programs) because you don’t have to worry about travelling…It’s in the comfort of your own home so that also helps when you’re participating. You know you’re in a safe space.” – Focus Group #2

Resource while on waitlist

The modules were described as a good resource for people waitlisted for therapy groups; modules provided them with supportive tools and resources while waiting. The module format could be used to reduce the wait for other groups if it was found to be sufficient, or as a refresher of content while waiting for different groups in the program. One participant felt the modules were an introduction that strengthened the trust and connection felt between participants and the TTP.

“It’s a good collection of first-step information that you can’t necessarily find by yourself.” – Focus Group #2

Opportunity for interactivity

Several participants recommended weekly synchronous video group sessions to complement the asynchronous virtual modules. They felt it would help consolidate module content, provide motivation to complete the modules, and enforce the sense of not being alone. Concerns included whether the group should be optional or required, whether an hour is enough, and how many people would attend an optional group format. Other suggestions for increasing interactivity included discussion boards, testimonials, and a Q&A opportunity with a therapist from TTP.

“I find it hard sometimes to do those kinds of exercises without knowing that I’ll have somebody to talk to about it, or that there will be something else. I tend just to skip them, but if I knew, oh, okay, there’s this meeting I can drop-in to it gives me more motivation.” – Focus Group #1

“[Live virtual groups] would be beneficial not only for accountability for myself, but then again, reiterating on that sense of not being alone. It’s amazing how you may hear the same response from someone else and think, oh, I’m not the only one thinking that way, you know, so it would be nice, yeah.” - Focus Group #1

Discussion

In this focus group study, we explored participants insight and perspectives on the initial design and development of our first two modules of eR&R. We also specifically asked for reflections on the technological aspects and asynchronous nature of the program. These perspectives can inform the further development of eR&R, but also can provide insight into the design, development, and implementation of asynchronous virtual interventions for mental health. Our study highlights essential points that are important to consider when creating a sustainable virtual or hybrid asynchronous program such as the incorporating multimedia content, utilizing user friendly platforms, and incorporating interactive components. Importantly, our findings also offer important information relevant to asynchronous treatment programs for complex populations. The self-pacing aspect helped with self-regulation and with absorption of the material. Being able to access care from one’s home environment also helped increase participants feelings of safety.

The use of technology for virtual interventions can present several potential concerns outlined in the literature, including technical limitations, the need for computer literacy and access, varying comfort level with virtual formats, low adherence, safety-related concerns, and privacy risks (Alhajri et al., Citation2022; Andersson & Titov, Citation2014). Our focus group participants identified some similar challenges such as experiencing technical glitches with audio or video quality, and concerns around low motivation. Nevertheless, the participants in our study were largely comfortable using technology and experienced only minor technical issues when accessing and using eR&R. Despite their reported comfort level, participants underscored that computer literacy and comfort level with virtual formats must be considered when designing virtual programs.

Participant perceptions that virtual modules could increase access to care, decrease wait times, and were convenient are reflective of those reported in the literature (Mandal et al., Citation2022; Tenforde et al., Citation2020). The multimedia format of the eR&R modules was well-received for its content delivery and appropriate balance of complexity and volume. Participants especially valued the self-paced nature, allowing them to access the content at their own convenience. However, participants suggested that the virtual program should provide more clarity on how the information could be applied in practice. To provide a better learning experience, additional practical strategies will be available in the next phase of development which will enable participants to consolidate their knowledge more effectively.

The literature has raised concerns that virtual interventions, particularly asynchronous ones, may lack the sense of relational connectedness that can be found in in-person groups (Berger, Citation2017; Smith-Merry et al., Citation2019). Some participants wondered about potential problems with low motivation levels or feeling disconnected when accessing asynchronous services. However, participants also reported a sense of relational connectedness with the therapists through the multimedia content alone which is important in building trust and a sense of safety. To address concerns around interactivity and connectedness, in future iterations of eR&R we will introduce a one-hour synchronous weekly group, allowing participants to connect and interact with each other, as well as receive answers to their questions from TTP therapists in real-time.

Our study was limited by a small sample size and a narrow focus on childhood interpersonal trauma, which may mean our findings would not be applicable to other traumatized populations. To protect anonymity in our small sample size, we did not require participants to share specific information about their background characteristics and are thus unable to comment on demographics aside from gender. Future studies evaluating eR&R will analyze a fuller set of demographic data and could control for how individuals are selected for participation to account for proportional representation of demographic composition of the TTP. Most of the existing research on virtual interventions for PTSD have focused on internet-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Andrews et al., Citation2018; CADTH, 2020; Karyotaki et al., Citation2017; Sijbrandij et al., Citation2016; Simon et al., Citation2021) or exposure therapy with veterans (Jones et al., Citation2020; McLean et al., Citation2021). These interventions tend to be diagnosis-focused and specify PTSD as an inclusion criteria, whereas our program aims to have a client-centred approach and, although many clients may meet criteria for PTSD diagnosis, the program’s eligibility criteria are broader and focus on survivors’ self-identified experience and sequelae of CIT. This makes it difficult to draw direct comparisons to our intervention. Additionally, the literature tends to compare outcomes between in-person and virtual services (Gros et al., Citation2011; Morland et al., Citation2015; Valentine et al., Citation2020). To gain greater insight into the efficacy of virtual asynchronous interventions for sequelae of CIT, more research is needed to compare them with other non-CBT or exposure-based virtual interventions (Chan et al., Citation2018; Hilty et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2020; Lewis et al., Citation2018; Van Ameringen et al., Citation2017).

The findings of our study are particularly pertinent considering the current healthcare climate, where due to the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual care has become increasingly necessary and normalized. The growing comfort with virtual platforms to access care has likely (Mangalji et al., Citation2022, Stamenova et al., Citation2022) contributed to the positive response to our asynchronous virtual intervention, including platforms like PTSD coach, Interapy, and PTSDialogue (Han et al., Citation2021; Knaevelsrud & Maercker, Citation2007; Kuhn et al., Citation2017;). Future studies should look into the impact of factors such as demographics, years of past therapy experience and types of past therapy modalities, and the presence of mental health diagnoses and comorbid disorders.

Our research contributes to the growing body of evidence on the development and evaluation of virtual treatment interventions for trauma survivors. Our findings are in line with research that suggests virtual treatment interventions for trauma and PTSD are associated with high levels of satisfaction and acceptability (Brady, 2020; Ontario Health, 2021; Philippe et al., Citation2022). In addition, despite the hesitance of healthcare providers to offer asynchronous or hybrid services to people with complex clinical presentations, our study suggests that such interventions may be both tolerable and beneficial. However, the efficacy of virtual interventions for trauma and PTSD remains unclear (Lungu et al., Citation2022; Rasing et al., Citation2019; Søgaard Neilsen & Wilson Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2021). By using User-Centered Design principles, we aimed to enhance our ability to adapt our intervention to best meet the needs of key stakeholders, including service users and healthcare providers. We will continue to develop the remaining modules of eR&R and will conduct a pilot study to explore feasibility, acceptability, and usability, followed by a clinical trial to evaluate efficacy. The eR&R intervention has the potential to increase access to a stabilization-focused intervention.

Authors’ contributions

DCR, NM, SV, TB, SS, and DR made major contributions to the conception and design of the study. DCR and AB conducted the focus groups. DCR, AKT, NM and AB were all major contributors in writing the manuscript. AKT and AB analyzed and interpreted the data from all focus groups. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscripts for submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

| List of abbreviations | ||

| CIT | = | Childhood interpersonal trauma |

| TTP | = | Trauma Therapy Program |

| WCH | = | Women’s College Hospital |

| R&R | = | Resourced & Resilient |

| UAP | = | User Advisory Panel |

| eR&R | = | electronic Resourced & Resilient |

| CBT | = | cognitive behavioural therapy |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eileen Wang for assistance with data organization and analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [DCR]. The full transcripts are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise research participant privacy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Taillieu, T., Cheung, K., & Sareen, J. (2014). Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 186(9), E324–E332. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131792

- Alcalá, H. E., Valdez-Dadia, A., & von Ehrenstein, O. S. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and access and utilization of health care. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 40(4), 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx155

- Alhajri, N., Simsekler, M. C. E., Alfalasi, B., Alhashmi, M., Memon, H., Housser, E., Abdi, A. M., Balalaa, N., Al Ali, M., Almaashari, R., Al Memari, S., Al Hosani, F., Al Zaabi, Y., Almazrouei, S., & Alhashemi, H. (2022). Exploring quality differences in telemedicine between hospital outpatient departments and community clinics: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Medical Informatics, 10(2), e32373. https://doi.org/10.2196/32373

- Alpert, E., Hayes, A. M., Barnes, J. B., & Sloan, D. M. (2020). Predictors of dropout in cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: An examination of trauma narrative content. Behavior Therapy, 51(5), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.11.003

- Altman, M., Huang, T. T. K., & Breland, J. Y. (2018). Design thinking in health care. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, E117. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180128

- Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Titov, N., & Lindefors, N. (2019). Internet interventions for adults with anxiety and mood disorders: A narrative umbrella review of recent meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 64(7), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719839381

- Andersson, G., & Titov, N. (2014). Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry: official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20083

- Andrews, G., Basu, A., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., English, C. L., & Newby, J. M. (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001

- Atwoli, L., Platt, J. M., Basu, A., Williams, D. R., Stein, D. J., & Koenen, K. C. (2016). Associations between lifetime potentially traumatic events and chronic physical conditions in the South African stress and health survey: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0929-z

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Ramos Rodriguez, G., Sethi, D., & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Public Health, 4(10), e517–e528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

- Berger, T. (2017). The therapeutic alliance in internet interventions: A narrative review and suggestions for future research. Psychotherapy Research: journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 27(5), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1119908

- Bisson, J. I., Ariti, C., Cullen, K., Kitchiner, N., Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Simon, N., Smallman, K., Addison, K., Bell, V., Brookes-Howell, L., Cosgrove, S., Ehlers, A., Fitzsimmons, D., Foscarini-Craggs, P., Harris, S. R. S., Kelson, M., Lovell, K., McKenna, M., … Williams-Thomas, R. (2022). Guided, internet based, cognitive behavioural therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (RAPID). BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 377, e069405. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-069405

- Bowlus, A., McKenna, K., Day, T., & Wright, D. (2003). The economic costs and consequences of child abuse in Canada. Law Commission of Canada.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bröcker, E., Olff, M., Suliman, S., Kidd, M., Mqaisi, B., Greyvenstein, L., Kilian, S., & Seedat, S. (2022). A clinician-monitored ‘PTSD Coach’ intervention: Findings from two pilot feasibility and acceptability studies in a resource-constrained setting. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2107359. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2107359

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet (London, England), 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

- Chan, S., Li, L., Torous, J., Gratzer, D., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2018). Review of use of asynchronous technologies incorporated in mental health care. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(10), 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0954-3

- Cloitre, M., Khan, C., Mackintosh, M. A., Garvert, D. W., Henn-Haase, C. M., Falvey, E. C., & Saito, J. (2019). Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ACES and physical and mental health. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 11(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000374

- Cloitre, M., Stolbach, B. C., Herman, J. L., van der Kolk, B., Pynoos, R., Wang, J., & Petkova, E. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20444

- Cloitre, M., Stovall-McClough, K. C., Nooner, K., Zorbas, P., Cherry, S., Jackson, C. L., Gan, W., & Petkova, E. (2010). Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247

- Cotter, A. (2021). Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019. Juristat, 41(1), 1–37. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00014-eng.htm

- Coventry, P. A., Meader, N., Melton, H., Temple, M., Dale, H., Wright, K., Cloitre, M., Karatzias, T., Bisson, J., Roberts, N. P., Brown, J. V. E., Barbui, C., Churchill, R., Lovell, K., Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M, Medical Research Council Guidance. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 337, a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Damian, A. J., Gallo, J. J., & Mendelson, T. (2018). Barriers and facilitators for access to mental health services by traumatized youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.003

- Deady, M., Choi, I., Calvo, R. A., Glozier, N., Christensen, H., & Harvey, S. B. (2017). eHealth interventions for the prevention of depression and anxiety in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1473-1

- Dopp, A. R., Parisi, K. E., Munson, S. A., & Lyon, A. R. (2019). A glossary of user-centered design strategies for implementation experts. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 9(6), 1057–1064. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby119

- Erbe, D., Eichert, H. C., Riper, H., & Ebert, D. D. (2017). Blending face-to-face and Internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(9), e306. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6588

- Ferrucci, F., Jorio, M., Marci, S., Bezenchek, A., Diella, G., Nulli, C., Miranda, F., & Castelli-Gattinara, G. (2021). A web-based application for complex health care populations: User-centered design approach. JMIR Human Factors, 8(1), e18587. https://doi.org/10.2196/18587

- Fortney, J. C., Pyne, J. M., Kimbrell, T. A., Hudson, T. J., Robinson, D. E., Schneider, R., Moore, W. M., Custer, P. J., Grubbs, K. M., & Schnurr, P. P. (2015). Telemedicine-based collaborative care for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1575

- Gaebel, W., Großimlinghaus, I., Mucic, D., Maercker, A., Zielasek, J., & Kerst, A. (2017). EPA guidance on eMental health interventions in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 41(1), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.001

- Gilmore, A. K., Wilson, S. M., Skopp, N. A., Osenbach, J. E., & Reger, G. (2017). A systematic review of technology-based interventions for co-occurring substance use and trauma symptoms. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 23(8), 701–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16664205

- Göttgens, I., & Oertelt-Prigione, S. (2021). The application of human-centered design approaches in health research and innovation: A narrative review of current practices. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(12), e28102. https://doi.org/10.2196/28102

- Gould, C. E., Loup, J., Scales, A. N., Juang, C., Carlson, C., Ma, F., & Sakai, E. Y. (2020). Development and refinement of educational materials to help older veterans use VA mental health mobile apps. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 51(4), 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000354

- Graziani, G., Aylward, B. S., Fung, V., & Kunkle, S. (2022). Changes in healthcare costs following engagement with a virtual mental health system: A matched cohort study of healthcare claims data. Procedia Computer Science, 206, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.09.096

- Gros, D. F., Yoder, M., Tuerk, P. W., Lozano, B. E., & Acierno, R. (2011). Exposure therapy for PTSD delivered to veterans via telehealth: Predictors of treatment completion and outcome and comparison to treatment delivered in person. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.005

- Han, H. J., Mendu, S., Jaworski, B. K., E Owen, J., & Abdullah, S. (2021). PTSDialogue: Designing a conversational agent to support individuals with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder [Paper presentation]. Adjunct Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, September) (pp. 198–203). https://doi.org/10.1145/3460418.3479332

- Hilty, D. M., Chan, S., Hwang, T., Wong, A., & Bauer, A. M. (2017). Advances in mobile mental health: Opportunities and implications for the spectrum of e-mental health services. mHealth, 3, 34–34. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.06.02

- Hollis, C., Falconer, C. J., Martin, J. L., Whittington, C., Stockton, S., Glazebrook, C., & Davies, E. B. (2017). Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – a systematic and meta-review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(4), 474–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12663

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

- Jaspers, M. W., Steen, T., van den Bos, C., & Geenen, M. (2004). The think aloud method: A guide to user interface design. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 73(11-12), 781–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.08.003

- Jones, C., Miguel-Cruz, A., Smith-MacDonald, L., Cruikshank, E., Baghoori, D., Kaur Chohan, A., Laidlaw, A., White, A., Cao, B., Agyapong, V., Burback, L., Winkler, O., Sevigny, P. R., Dennett, L., Ferguson-Pell, M., Greenshaw, A., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2020). Virtual trauma-focused therapy for military members, veterans, and public safety personnel with posttraumatic stress injury: Systematic scoping review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(9), e22079. https://doi.org/10.2196/22079

- Karyotaki, E., Riper, H., Twisk, J., Hoogendoorn, A., Kleiboer, A., Mira, A., Mackinnon, A., Meyer, B., Botella, C., Littlewood, E., Andersson, G., Christensen, H., Klein, J. P., Schröder, J., Bretón-López, J., Scheider, J., Griffiths, K., Farrer, L., Huibers, M. J. H., … Cuijpers, P. (2017). Efficacy of self-guided Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0044

- Kerst, A., Zielasek, J., & Gaebel, W. (2020). Smartphone applications for depression: A systematic literature review and a survey of health care professionals’ attitudes towards their use in clinical practice. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 270(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0974-3

- Knaevelsrud, C., & Maercker, A. (2007). Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry, 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-7-13

- Kruse, C. S., Atkins, J. M., Baker, T. D., Gonzales, E. N., Paul, J. L., & Brooks, M. (2018). Factors influencing the adoption of telemedicine for treatment of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 50(5), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2302

- Kuhn, E., Kanuri, N., Hoffman, J. E., Garvert, D. W., Ruzek, J. I., & Taylor, C. B. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone app for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(3), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000163

- Lewis, S. J., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Matthews, T., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., Stahl, D., Teng, J. Y., & Danese, A. (2019). The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30031-8

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Starling, E., & Bisson, J. I. (2020). Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1729633. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1729633

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Bethell, A., Robertson, L., & Bisson, J. I. (2018). Internet-based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12(12), CD011710. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011710.pub2

- Liu, C., Lee, J. H., Gupta, A. J., Tucker, A., Larkin, C., Turimumahoro, P., Katamba, A., Davis, J. L., & Dowdy, D. (2022). Cost-effectiveness analysis of human-centred design for global health interventions: A quantitative framework. BMJ Global Health, 7(3), e007912. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007912

- Lungu, A., Wickham, R. E., Chen, S. Y., Jun, J. J., Leykin, Y., & Chen, C. E. (2022). Component analysis of a synchronous and asynchronous blended care CBT intervention for symptoms of depression and anxiety: Pragmatic retrospective study. Internet Interventions, 28, 100536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2022.100536

- Lyon, A. R., & Koerner, K. (2016). User-centered design for psychosocial intervention development and implementation. Clinical Psychology: A Publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 23(2), 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12154

- Maercker, A., Cloitre, M., Bachem, R., Schlumpf, Y. R., Khoury, B., Hitchcock, C., & Bohus, M. (2022). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet (London, England), 400(10345), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

- Mandal, S., Wiesenfeld, B. M., Mann, D., Lawrence, K., Chunara, R., Testa, P., & Nov, O. (2022). Evidence for telemedicine’s ongoing transformation of health care delivery since the onset of COVID-19: Retrospective observational study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(10), e38661. https://doi.org/10.2196/38661

- Mangalji, A., Chahal, P., & Cherukupalli, A. (2022). Evaluating patient perceptions of quality of care through telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. BC Medical Journal, 64(6), 265–267.

- Martínez, P., Rojas, G., Martínez, V., Lara, M. A., & Pérez, J. C. (2018). Internet-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of depression in people living in developing countries: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.079

- McGrath, P., Wozney, L., Bishop, A., Curran, J., Chorney, J., & Rathore, S. (2018). Toolkit for e-mental health implementation. Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., Hill, E. D., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815–830.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011

- McLean, C. P., Foa, E. B., Dondanville, K. A., Haddock, C. K., Miller, M. L., Rauch, S. A. M., Yarvis, J. S., Wright, E. C., Hall-Clark, B. N., Fina, B. A., Litz, B. T., Mintz, J., Young-McCaughan, S., & Peterson, A. L, STRONG STAR Consortium. (2021). The effects of web-prolonged exposure among military personnel and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 13(6), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000978

- McTavish, J. R., Chandra, P. S., Stewart, D. E., Herrman, H., & MacMillan, H. L. (2022). Child maltreatment and intimate partner violence in mental health settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315672

- Melton, H., Meader, N., Dale, H., Wright, K., Jones-Diette, J., Temple, M., Shah, I., Lovell, K., McMillan, D., Churchill, R., Barbui, C., Gilbody, S., & Coventry, P. (2020). Interventions for adults with a history of complex traumatic events: The INCiTE mixed-methods systematic review. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 24(43), 1–312. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24430

- Mohr, D. C., Riper, H., & Schueller, S. M. (2018). A solution-focused research approach to achieve an implementable revolution in digital mental health. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 113–114. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3838

- Mongelli, F., Georgakopoulos, P., & Pato, M. T. (2020). Challenges and opportunities to meet the mental health needs of underserved and disenfranchised populations in the United States. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing), 18(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20190028

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 350, h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

- Moreno, C., Wykes, T., Galderisi, S., Nordentoft, M., Crossley, N., Jones, N., Cannon, M., Correll, C. U., Byrne, L., Carr, S., Chen, E. Y. H., Gorwood, P., Johnson, S., Kärkkäinen, H., Krystal, J. H., Lee, J., Lieberman, J., López-Jaramillo, C., Männikkö, M., … Arango, C. (2020). How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(9), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2

- Morland, L. A., Mackintosh, M. A., Rosen, C. S., Willis, E., Resick, P., Chard, K., & Frueh, B. C. (2015). Telemedicine versus in-person delivery of cognitive processing therapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority trail. Depression and Anxiety, 32(11), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22397

- Nickerson, A., Byrow, Y., Pajak, R., McMahon, T., Bryant, R. A., Christensen, H., & Liddell, B. J. (2020). Tell Your Story’: A randomized controlled trial of an online intervention to reduce mental health stigma and increase help-seeking in refugee men with posttraumatic stress. Psychological Medicine, 50(5), 781–792. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000606

- Olthuis, J. V., Wozney, L., Asmundson, G. J., Cramm, H., Lingley-Pottie, P., & McGrath, P. J. (2016). Distance-delivered interventions for PTSD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 44, 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.010

- Pace, C. S., Muzi, S., Rogier, G., Meinero, L. L., & Marcenaro, S. (2022). The Adverse Childhood Experiences - International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in community samples around the world: A systematic review (part I). Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105640

- Patel, S., Akhtar, A., Malins, S., Wright, N., Rowley, E., Young, E., Sampson, S., & Morriss, R. (2020). The acceptability and usability of digital health interventions for adults with depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e16228. https://doi.org/10.2196/16228

- Philippe, T. J., Sikder, N., Jackson, A., Koblanski, M. E., Liow, E., Pilarinos, A., & Vasarhelyi, K. (2022). Digital Health interventions for delivery of mental health care: Systematic and comprehensive meta-review. JMIR Mental Health, 9(5), e35159. https://doi.org/10.2196/35159

- Rasing, S. P. A., Stikkelbroek, Y. A. J., & Bodden, D. H. M. (2019). Is digital treatment the holy grail? Literature review on computerized and blended treatment for depressive disorders in youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010153

- Rauschenberg, C., Schick, A., Goetzl, C., Roehr, S., Riedel-Heller, S. G., Koppe, G., Durstewitz, D., Krumm, S., & Reininghaus, U. (2021). Social isolation, mental health, and use of digital interventions in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative survey. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 64(1), e20. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.17

- Robards, F., Kang, M., Usherwood, T., & Sanci, L. (2018). How marginalized young people access, engage with, and navigate health-care systems in the digital age: Systematic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 62(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.018

- Sandre, A. R., & Newbold, K. B. (2016). Telemedicine: Bridging the gap between refugee health and health services accessibility in Hamilton, Ontario. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 32(3), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.40396

- Saunders, B. E., & Adams, Z. W. (2014). Epidemiology of traumatic experiences in childhood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 167–184, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.12.003

- Schrader, C., & Ross, A. (2021). A review of PTSD and current treatment strategies. Missouri Medicine, 118(6), 546–551.

- Sijbrandij, M., Kunovski, I., & Cuijpers, P. (2016). Effectiveness of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 33(9), 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22533

- Simon, N., McGillivray, L., Roberts, N. P., Barawi, K., Lewis, C. E., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Acceptability of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (i-CBT) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1646092. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1646092

- Simon, N., Robertson, L., Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Bethell, A., Dawson, S., & Bisson, J. I. (2021). Internet-based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5(5), CD011710. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011710.pub3

- Sloan, D. M., Gallagher, M. W., Feinstein, B. A., Lee, D. J., & Pruneau, G. M. (2011). Efficacy of telehealth treatments for posttraumatic stress-related symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(2), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2010.550058

- Smith-Merry, J., Goggin, G., Campbell, A., McKenzie, K., Ridout, B., & Baylosis, C. (2019). Social connection and online engagement: Insights from interviews with users of a mental health online forum. JMIR Mental Health, 6(3), e11084. https://doi.org/10.2196/11084

- Søgaard Neilsen, A., & Wilson, R. L. (2019). Combining e-mental health intervention development with human computer interaction (HCI) design to enhance technology-facilitated recovery for people with depression and/or anxiety conditions: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12527

- Stamenova, V., Chu, C., Pang, A., Fang, J., Shakeri, A., Cram, P., Bhattacharyya, O., Bhatia, R. S., & Tadrous, M. (2022). Virtual care use during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on healthcare utilization in patients with chronic disease: A population-based repeated cross-sectional study. PloS One, 17(4), e0267218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267218

- Strudwick, G., Impey, D., Torous, J., Krausz, R. M., & Wiljer, D. (2020). Advancing e-mental health in Canada: Report from a multistakeholder meeting. JMIR Mental Health, 7(4), e19360. https://doi.org/10.2196/19360

- Sunjaya, A. P., Chris, A., & Novianti, D. (2020). Efficacy, patient-doctor relationship, costs and benefits of utilizing telepsychiatry for the management of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A systematic review. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0024

- Tenforde, A. S., Borgstrom, H., Polich, G., Steere, H., Davis, I. S., Cotton, K., O’Donnell, M., & Silver, J. K. (2020). Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: A survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 99(11), 977–981. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001571

- Thinkific. (n.d). https://www.thinkific.com/

- Torous, J., & Keshavan, M. (2020). COVID-19, mobile health and serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Research, 218, 36–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.013

- Turgoose, D., Ashwick, R., & Murphy, D. (2018). Systematic review of lessons learned from delivering tele-therapy to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(9), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17730443

- Valentine, L. M., Donofry, S. D., Broman, R. B., Smith, E. R., Rauch, S. A., & Sexton, M. B. (2020). Comparing PTSD treatment retention among survivors of military sexual trauma utilizing clinical video technology and in-person approaches. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(7–8), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X19832419

- Van Ameringen, M., Turna, J., Khalesi, Z., Pullia, K., & Patterson, B. (2017). There is an app for that! The current state of mobile applications (apps) for DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and mood disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 34(6), 526–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22657

- van Lotringen, C. M., Jeken, L., Westerhof, G. J., Ten Klooster, P. M., Kelders, S. M., & Noordzij, M. L. (2021). Responsible relations: A systematic scoping review of the therapeutic alliance in text-based digital psychotherapy. Frontiers in Digital Health, 3, 689750. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.689750

- Vial, S., Boudhraâ, S., & Dumont, M. (2022). Human-centered design approaches in digital mental health interventions: Exploratory mapping review. JMIR Mental Health, 9(6), e35591. https://doi.org/10.2196/35591

- Whaibeh, E., Mahmoud, H., & Naal, H. (2020). Telemental health in the context of a pandemic: The COVID-19 Experience. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7(2), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00210-2

- Wu, M. S., Wickham, R. E., Chen, S. Y., Chen, C., & Lungu, A. (2021). Examining the impact of digital components across different phases of treatment in a blended care cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for depression and anxiety: Pragmatic retrospective study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(12), e33452. https://doi.org/10.2196/33452

- Zhou, X., Snoswell, C. L., Harding, L. E., Bambling, M., Edirippulige, S., Bai, X., & Smith, A. C. (2020). The role of telehealth in reducing the mental health burden from COVID-19. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 26(4), 377–379. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0068