Abstract

Background

Social media has become a dominant part of daily lives for many, but excessive use may lead to an experience of stress. Only relatively few studies have investigated social media’s influence on mental health.

Aims

We aimed to investigate whether social media use is associated with perceived stress and changes in perceived stress over 18 months.

Methods

The study population consisted of 25,053 adults (mean age 42.8; 62% women) from the SmartSleep Study. Self-reported frequency of social media use, of 10 specific social media platforms, and of perceived stress (the Perceived Stress Scale 4 item) was obtained at baseline and 18-months follow-up (N = 1745). The associations were evaluated at baseline and follow-up using multiple linear regression models adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

Compared to non-use, high social media use (at least every second hour) was associated with a slightly higher perceived stress level at baseline. No association was found between the frequency of social media use and changes in perceived stress during follow-up. Only small differences in these associations were noted across social media platforms.

Conclusions

Further studies are needed to comprehensively explore the relationship between excessive social media use and mental health, recognizing different characteristics across social media platforms.

Introduction

Stress and poor mental health are increasing public health issues, affecting millions of people’s quality of life and health trajectories globally (Rehm & Shield, Citation2019; Vos et al., Citation2020). The increase in mental health problems parallels a similar increase in the use of social media (Statista, Citation2022b, Citation2022a), and the relation between social media use and mental health warrants further investigation.

Social media platforms have revolutionized how people interact and communicate, facilitating numerous daily social exchanges. They differ from traditional media by providing a comforting shortcut to entertainment, conversations, and acknowledgement anytime, anywhere. In 2021, over 4.3 billion people were using social media worldwide, corresponding to over half of the global population (Statista, Citation2022b). Similar to other western countries, Denmark has a high proportion of social media users, with 90% of the population above 12 years having at least one social media profile (Ministry of Culture Denmark, Citation2021). On average, they spend 47 min daily on social media, with Facebook, Messenger, and Instagram being the most common social media platforms in 2020 (Ministry of Culture Denmark, Citation2021).

As a result of the features behind social media platforms, social media use may function as a stressor that can affect an individual’s perceived stress and, in the longer term, a more chronic stress response. Some users have described how social media can be perceived as an online display window of how others are doing extremely well, leaving them with less positive feelings about themselves and their life situation (Hjetland et al., Citation2021; Royal Society for Public Health, Citation2017). Social media can trigger approval anxiety and an exaggerated desire to be connected with what others are doing, often referred to as fear of missing out (FoMO) (Wolfers & Utz, Citation2022). The social rewards associated with likes and notifications on social media have been compared to other addictive rewards (Royal Society for Public Health, Citation2017; Turel et al., Citation2018; Warrender & Milne, Citation2020), making it hard for the user to manage time. Consequently, users experience a demand to be permanently available (Wolfers & Utz, Citation2022), displacing time from other vital activities, such as sleep, physical activity and face-to-face interaction, that are protective for mental health (Naslund et al., Citation2020).

Experimental studies have shown that a break from social media may lead to better mental health, including lower psychological and physiological stress, especially among heavy social media users (Tromholt, Citation2016; Turel et al., Citation2018; Vanman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, several observational studies have suggested that high social media use is related to mental health problems (Alonzo et al., Citation2021; Hussain & Griffiths, Citation2018; Karim et al., Citation2020; Keles et al., Citation2020; Schønning et al., Citation2020; Shannon et al., Citation2022; Sharma et al., Citation2020), while other studies found no associations (e.g. Aalbers et al., Citation2019; Coyne et al., Citation2020; Khodarahimi & Fathi, Citation2017). The existing evidence is predominantly based on cross-sectional analyses undertaken in small and selected samples, particularly among students. Moreover, the majority of the previous studies exclusively assessed anxiety and depression as mental health outcomes (Karim et al., Citation2020; Keles et al., Citation2020), and were limited to Facebook use (Keles et al., Citation2020; Schønning et al., Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2020) despite the fact that most adults engage with several social media platforms (Ministry of Culture Denmark, Citation2021). This is particularly important, as previous studies have suggested that the number of social media platforms used is more influential on mental health than the time spent on social media (Bevan et al., Citation2014; Primack et al., Citation2017). Also, social media platforms differ in the online environment as some are more dominated by social interactions, while others are dominated by passive browsing use (Vanman et al., Citation2018; Verduyn et al., Citation2015), which potentially can yield different stressors (Wolfers et al., Citation2020). Therefore, differences between social media platforms are equally important to consider.

In this study, we investigated whether social media use is associated with perceived stress in a large and diverse sample of 25,053 adults. We also assessed changes in perceived stress over 18 months in a subset of the population. Finally, we explored whether the use of 10 specific social media platforms and the total number of frequently used platforms are associated with perceived stress.

Materials and methods

Study population

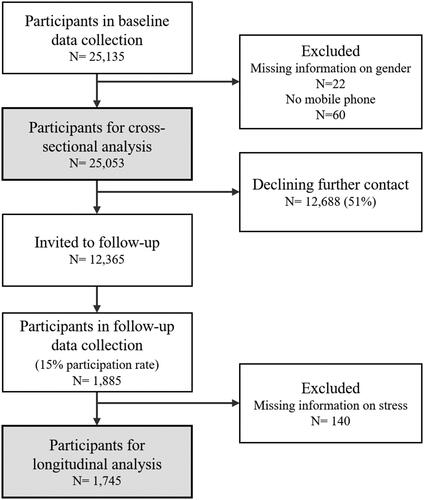

We used data from the Citizen Science Sample of the SmartSleep Study (Rod et al., Citation2023). The participants were initially recruited to the study in November 2018 by utilizing a citizen science approach (Buyx et al., Citation2017; Den Broeder et al., Citation2016). In total, 25,135 adults aged 16 years and above participated in an online questionnaire about smartphone use, sleep, and health. In comparison with the general Danish population, the Citizen Science sample includes a larger proportion of younger people, women and individuals with a higher education (Supplementary Table 1), assumingly as a result of the self-selection sampling strategy. Data collection has been described in detail elsewhere (Dissing et al., Citation2021). We excluded participants with missing information on gender (N = 22) and those reporting not having a smartphone (N = 60), leaving 25,053 participants eligible for the cross-sectional analysis. Of these, 12,365 participants (49%) indicated that we could contact them via email for future studies.

Approximately 18 months later (interquartile range (IQR): 530–555 d), a few months after the national COVID-19 pandemic lock-down in Denmark, these participants were invited via email to participate in a follow-up study. The follow-up study included a more comprehensive questionnaire about smartphone and sleep behaviour, and mental and physical health. Data were collected by a customized smartphone app developed for the purpose (the SmartSleep app), which participants had to download to answer the questionnaire (more details about data collection and all included measures in Rod et al., Citation2023). A total of 1885 participants completed the follow-up questionnaire (15% response rate). We excluded participants with missing information on perceived stress (N = 140), leaving 1745 participants eligible for the longitudinal analysis. Compared with the baseline population, the follow-up sample included a larger proportion of female participants, participants with higher education and with medium social media use, and a smaller proportion of participants with no social media use (Supplementary Table 2). Participants in the follow-up sample reported a slightly lower perceived stress score at baseline (mean score: 5.2) compared to the baseline population (mean score: 5.5). outlines the flowchart of the study population.

Measures

Social media use

All information on the participants’ social media use was self-reported at baseline. Frequency of social media use was measured by asking the participants how often they used social media with six response options defined as; No use (“Never”), low use (“Weekly or less” and “Once a day”), medium use (“Several times a day”) to high use (“Every second hour” and “Every hour”). Frequent use of specific social media platforms was assessed by asking the participants to indicate which social media platforms among the 10 common social media platforms in Denmark they frequently used. The response options included: Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, Pinterest, YouTube, Reddit, WhatsApp, Messenger, Other and “I do not use social media”. The participants could choose multiple options. The number of frequently used social media platforms was defined as the sum of social media platforms the participants had indicated to use frequently, thus ranging from 0 to 11 by including the category of Other together with the 10 specified social media platforms.

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured at baseline and follow-up by a Danish consensus translation of the short version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) (Cohen et al., Citation1983; Eskildsen et al., Citation2015). The four-item PSS instrument measures the frequency of feeling stressed on a five-point Likert Scale, resulting in a score ranging between 0 and 16, where higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress.

Sociodemographic covariates

The participants’ age, gender (male; female; other), educational level (low [primary school]; medium [upper secondary school; technical vocational education]; high [higher education]; other), occupational status (employed; student; unemployed; outside labour market; long-term sick leave; other) and cohabitation status (living alone; not living alone) were assessed in the baseline survey.

Statistical analyses

First, baseline characteristics were explored according to the frequency of social media use.

In the baseline population (N = 25,053), cross-sectional associations between social media use and perceived stress were estimated as difference in mean values with 95% confidence intervals using multiple linear regression models adjusting confounders (age, gender, educational level, occupational status, and cohabitation status). Potential confounders were identified using the framework of a directed acyclic graph (DAG) (Greenland et al., Citation1999). The assumptions underlying a linear regression model were checked and no major violations were found.

For participants included in the follow-up study (N = 1745), we investigated the longitudinal associations between the frequency of social media use and changes in perceived stress over an 18-month period using multiple linear regression models adjusted for potential confounders and perceived stress at baseline. Again, no major violations of the assumptions for the linear regression model were found. We adjusted for baseline stress score in order to look for changes in stress over time, but the error associated with reported stress at baseline may be correlated with the associated error at follow-up, such analyses may be bias (Glymour et al., 2005). Thus, we have also presented the results without adjustment for baseline stress in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 3). The results are similar in the adjusted and unadjusted analyses.

Associations between specific social media platforms, the number of social media platforms, and perceived stress were assessed using linear regression models adjusting for potential confounders. The models for specific social media platforms were additionally mutually adjusted for the other social media platforms to assess the effect of each specific platform independently.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R.1.4.1.

Results

shows the baseline characteristics of the study population according to the frequency of social media use. Approximately half of the population (49%) reported a medium social media use (several times daily), and one in four (24%) reported a high social media use (every second hour or more). Only a small proportion (8%) of the population reported never using social media. On average, the participants reported frequently using three different social media platforms (IQR: two to four platforms). In general, women, younger participants, participants with lower educational levels, and students had a higher frequency of social media use, and more participants living alone reported no social media use.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics according to the frequency of social media use in a population of 25,053 Danish adults from the SmartSleep study.

Social media use was rather stable over time, with 82% of those reporting no social media use at baseline, reporting the same or a low use at follow-up (N = 1745). Similarly, among those who report high use (every hour or every second hour), 69% still reported high use 18 months later. On average, the participants in the follow-up sample (N = 1745) reported 0.6 points lower perceived stress score from baseline to 18-month follow-up time.

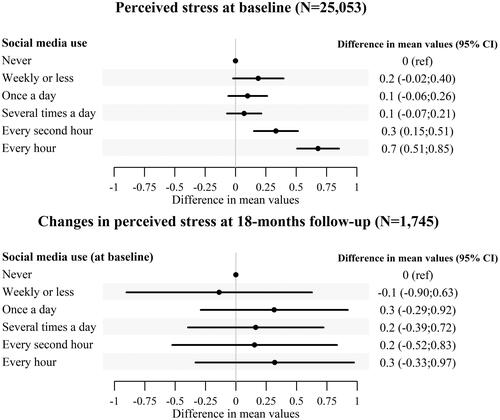

summarizes the associations between the frequency of social media use and perceived stress at baseline and changes in perceived stress at follow-up. Compared to non-users, those who reported social media use every second hour scored on average 0.3 points higher (95% CI: 0.15–0.51) on the baseline perceived stress score, and those who reported social media use every hour scored on average 0.7 points higher (95% CI: 0.51–0.85). The association was consistent among women and men, with minimal variations in the effect estimates (see Supplementary Figure S1). On the contrary, no associations were found between baseline frequency of social media use and changes in perceived stress at the 18-month follow-up in a subsample of the population (N = 1745). The same pattern was seen in a gender stratified analysis (Supplementary Figure S2). Restricting the baseline and follow-up sample to participants reporting some social media use, thus excluding individuals who reported no social media use at baseline, did not change the results (data now shown).

Figure 2. Associations between social media use, perceived stress, and changes in perceived stress. Perceived stress was measured using PSS-4 ranging from 0 to 16. Estimates were adjusted for gender, age, educational level, occupational status, and cohabitation.

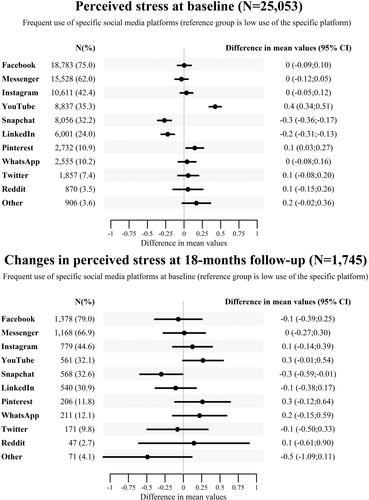

Among the baseline population, Facebook (75%) and Messenger (62%) were the most frequently used social media platforms, followed by Instagram (42%), YouTube (35%), and Snapchat (32%) (). Compared to low use, frequent use of YouTube was, on average, associated with 0.4 points higher (95% CI: 0.34–0.51) and Pinterest with 0.1 points higher (95% CI: 0.03–0.27) perceived stress score at baseline. Conversely, frequent use of Snapchat (−0.3 points, 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.17) and LinkedIn (−0.2 points, 95% CI: −0.31 to −0.13) were associated with slightly lower perceived stress scores at baseline. In the longitudinal analysis, there were no clear overall associations between different social media platforms and changes in perceived stress at follow-up. However, frequent Snapchat use compared to low use was associated with on average 0.3 points lower (95% CI: −0.59 to −0.01) perceived stress changes at the 18-month follow-up, whereas frequent YouTube use was associated with 0.3 points higher (95% CI: −0.01 to 0.54) perceived stress changes. The effect sizes were generally small, with absolute differences of less than 0.4 points on the PSS-4 scale ranging from 0 to 16.

Figure 3. Associations between use of specific social media platforms, perceived stress, and changes in perceived stress. Perceived stress was measured using PSS-4 ranging from 0 to 16. Estimates were adjusted for gender, age, educational level, occupational status, cohabitation, and use of the other social media platforms.

Overall, we found no clear associations between the total number of frequently used social media platforms and perceived stress at baseline or changes in perceived stress at follow-up (see Supplementary Figure S3).

Discussion

In a large and diverse sample of 25,053 adults from the general Danish population, we showed a very high prevalence of social media use, with one in four using social media every second hour or more. Frequent social media use was especially prevalent among women and young adults, and this is consistent with previous evidence showing the same pattern (Coyne et al., Citation2020; Ministry of Culture Denmark, Citation2021) and may also be related to the fact that women and younger people are more likely to be addicted to social media (Andreassen, Citation2015; Andreassen et al., Citation2016; Atroszko et al., Citation2018; Balcerowska et al., Citation2020). However, contrary to our hypothesis, high social media use was not consistently associated with higher levels of perceived stress, and the observed baseline associations were small, especially given the large sample size.

These results are in contrast to a previous experimental study of 555 American students, finding that a one-week break from Facebook was associated with decreased perceived stress, especially among excessive social media users (Turel et al., Citation2018). Similarly, other experimental studies have suggested the beneficial effects of not using social media (Rus & Tiemensma, Citation2017; Tromholt, Citation2016; Vanman et al., Citation2018). However, in line with our findings, a Dutch study found that the frequency of Facebook use was not associated with perceived stress six months later among adults (Wolfers et al., Citation2020). These differences between the population-based findings and the findings from experimental studies may relate to differences in the timeframe. Experimental studies often have a much shorter timeframe, and acute changes may not prevail over longer periods.

Previous literature within this area repeatedly emphasizes the complexity of social media use (e.g. Hjetland et al., Citation2021; Naslund et al., Citation2020; O’Reilly, Citation2020; Seabrook et al., Citation2016), underscoring that social media cannot be viewed as exclusively bad or good for mental health. High social media use may indicate a generally high level of social interaction, which is generally beneficial for mental health (e.g. Kawachi & Berkman, Citation2001). With a functional perspective, a recent review illustrates the complexity of social media use by demonstrating how social media use can have several functions; as a stressor, resource, and coping method (Wolfers & Utz, Citation2022). Adolescents have previously expressed that they use social media as a source of relaxation, distraction, and peer-to-peer-support, helping them reduce stress (Hjetland et al., Citation2021; O’Reilly, Citation2020; O’Reilly et al., Citation2022). For people experiencing mental health problems, social media can be a method to numb emotional pain and access peer support networks and self-support information (Naslund et al., Citation2020; Royal Society for Public Health, Citation2017). People experiencing high levels of stress may, therefore, also seek social media as a coping method, complicating the causal direction between social media use and mental health. Finally, the effect of social media use on mental health may also depend on other characteristics of social media use not covered in the present study. Thus, we suggest that future studies also include the duration and timing of use as well as function and content of social media use.

We found that the associations between social media use and perceived stress varied somewhat between social media platforms, in line with findings from other studies (Bevan et al., Citation2014; Brailovskaia & Margraf, Citation2018; Garett et al., Citation2017; Hampton et al., Citation2016). Again, it should be emphasized that the observed differences were small and most likely clinically insignificant. Also, we did not find an association between the number of frequently used social media platforms and perceived stress, contrary to previous studies (Bevan et al., Citation2014; Primack et al., Citation2017). However, these findings suggest that the impact of social media use may depend on the characteristics of the online environment, such as the degree of social interaction and self-representation.

We found that frequent use of Snapchat, where social interactions are dominant, was associated with slightly lower stress levels at follow-up. On the contrary, frequent use of YouTube, where social interactions are less dominant, was associated with slightly higher stress levels. Previous studies have distinguished between passive (browsing) and active (posting, messaging, and commenting) social media use and found that the effect differed accordingly (e.g. Faelens et al., Citation2019; Keum et al., Citation2022; Vanman et al., Citation2018; Wolfers et al., Citation2020). For example, a study found that more passive Facebook use was associated with higher stress levels six months later among users 18–39 years old (Wolfers et al., Citation2020). Future studies may benefit from increased attention to specific social media activities, including specific social media platforms, instead of only looking at frequency or duration of use. Greater attention to specific elements of social media use will also generate evidence and create an emphasis on theoretical causal assumptions that are robust against the fast-evolving platform changes (Parry et al., Citation2022).

Public health interventions against excessive social media use should acknowledge that social dynamics and relations today are deeply rooted in social media, particularly among young adults. Therefore, interventions should target educational activities aimed at responsible, conscious, and critical social media use.

Strengths and limitations

Social media patterns evolve fast and up-to-date evidence is essential to comprehensively assess the associations between social media use and mental health. Our study adds to this growing evidence base by including data from a large and diverse population sample, which included the assessment of several dimensions of social media use, and the use of the perceived stress scale with high reliability and validity (e.g. Lee, Citation2012). We were also able to adjust for several relevant confounding factors and assess changes in perceived stress over time. Combined, this also adds to the broader research area related to social media use and well-being, highlighting that social media use is neither good nor bad for an individual’s well-being (Valkenburg et al., Citation2022; Valkenburg, Citation2022). Due to this complexity, more attention towards the heterogeneity in social media use and content-based measures is needed.

However, some limitations are notable. First, all measures were self-reported. Previous studies have found that the validity of self-reported social media and smartphone use is limited, as participants cannot accurately estimate the time used (Boase & Ling, Citation2013; Junco, Citation2013; Kobayashi & Boase, Citation2012; Parry et al., Citation2021). Second, selection bias is a concern due to the initial recruitment strategy of the SmartSleep Study and due to the follow-up data collection being more demanding. Participants in the baseline sample were more likely to be women, have a high education, and to be younger compared to the general adult population in Denmark. In addition, participants in the follow-up sample were also more likely to be women and have a high education. Consequently, our results may be less generalizable to socially disadvantaged population groups which may have different social media patterns and, potentially, higher levels of stress. Third, the follow-up data collection happened a few months after the national COVID-19 pandemic lock-down, which most likely impacted participants’ levels of perceived stress and social media use at follow-up. These potential limitations are, however, unlikely to explain the lack of consistent associations between social media use and perceived stress in the current study.

Conclusion

High social media use is very common globally, making the potential public health implications high. We showed that frequent social media use was associated with slightly higher perceived stress levels at baseline, but this association was not confirmed in a longitudinal analysis. We also showed small differences in associations between social media use and perceived stress across social media platforms. The interrelationship between social media and stress is most likely complex with dynamic feedback, and public health interventions aimed at reducing excessive social media use should acknowledge that social dynamics today are deeply rooted in social media, particularly among young adults. Future preventive strategies may therefore benefit from paying attention to educational activities aimed at promoting responsible, conscious, and critical social media use instead of necessarily reducing use.

Ethics statement

All data collections in the Citizen Science Sample of the SmartSleep Study have been approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (no. 514-0237/18-3000 and 514-0288/19-3000). Participation in the study was voluntary and all participants agreed to participate in the study.

Authors contribution

All authors were involved in the conceptualization, methodology, and revisions of the paper and approved the submitted version. MN carried out data analysis and data visualization, and wrote the first draft of the paper.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (852.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns of the participants. For further information, contact the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, G., McNally, R. J., Heeren, A., de Wit, S., & Fried, E. I. (2019). Social media and depression symptoms: A network perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 148(8), 1454–1462. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000528

- Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., & Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 56, 101414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

- Andreassen, C. S. (2015). Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

- Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160

- Atroszko, P. A., Balcerowska, J. M., Bereznowski, P., Biernatowska, A., Pallesen, S., & Schou Andreassen, C. (2018). Facebook addiction among Polish undergraduate students: Validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.001

- Balcerowska, J. M., Bereznowski, P., Biernatowska, A., Atroszko, P. A., Pallesen, S., & Andreassen, C. S. (2020). Is it meaningful to distinguish between facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction? Psychometric analysis of facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction scales. Current Psychology, 41(2), 949–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00625-3

- Bevan, J. L., Gomez, R., & Sparks, L. (2014). Disclosures about important life events on Facebook: Relationships with stress and quality of life. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.021

- Boase, J., & Ling, R. (2013). Measuring mobile phone use: Self-report versus log data. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(4), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12021

- Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2018). What does media use reveal about personality and mental health? An exploratory investigation among German students. PLOS One, 13(1), e0191810. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191810

- Buyx, A., Del Savio, L., Prainsack, B., & Völzke, H. (2017). Every participant is a PI. Citizen science and participatory governance in population studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(2), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw204

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

- Den Broeder, L., Devilee, J., Van Oers, H., Schuit, A. J., & Wagemakers, A. (2016). Citizen Science for public health. Health Promotion International, 33(3), daw086. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw086

- Dissing, A. S., Andersen, T. O., Nørup, L. N., Clark, A., Nejsum, M., & Rod, N. H. (2021). Daytime and nighttime smartphone use: A study of associations between multidimensional smartphone behaviours and sleep among 24,856 Danish adults. Journal of Sleep Research, 30(6), e13356. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13356

- Eskildsen, A., Dalgaard, V. L., Nielsen, K. J., Andersen, J. H., Zachariae, R., Olsen, L. R., Jørgensen, A., & Christiansen, D. H. (2015). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish consensus version of the 10-item perceived stress scale. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 41(5), 486–490. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3510

- Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Fried, E., De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2019). Negative influences of Facebook use through the lens of network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.002

- Garett, R., Liu, S., & Young, S. D. (2017). A longitudinal analysis of stress among incoming college freshmen. Journal of American College Health, 65(5), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1312413

- Greenland, S., Pearl, J., & Robins, J. M. (1999). Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology, 10(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199901000-00008

- Hampton, K. N., Lu, W., & Shin, I. (2016). Digital media and stress: The cost of caring 2.0. Information, Communication & Society, 19(9), 1267–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186714

- Hjetland, G. J., Schønning, V., Hella, R. T., Veseth, M., & Skogen, J. C. (2021). How do Norwegian adolescents experience the role of social media in relation to mental health and well-being: A qualitative study. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00582-x

- Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Problematic social networking site use and comorbid psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of recent large-scale studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00686

- Junco, R. (2013). Comparing actual and self-reported measures of Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 626–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.007

- Karim, F., Oyewande, A. A., Abdalla, L. F., Chaudhry Ehsanullah, R., & Khan, S. (2020). Social media use and its connection to mental health: A systematic review. Cureus, 12(6), e8627. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627

- Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 78(3), 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

- Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

- Keum, B. T., Wang, Y.-W., Callaway, J., Abebe, I., Cruz, T., & O’Connor, S. (2022). Benefits and harms of social media use: A latent profile analysis of emerging adults. Current Psychology, 42(27), 23506–23518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03473-5

- Khodarahimi, S., & Fathi, R. (2017). The role of online social networking on emotional functioning in a sample of Iranian adolescents and young adults. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 35(2), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2017.1293587

- Kobayashi, T., & Boase, J. (2012). No such effect? The implications of measurement error in self-report measures of mobile communication use. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.679243

- Lee, E.-H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

- Ministry of Culture Denmark. (2021). Mediernes udvikling i Danmark—Internetbrug og sociale medier 2021 [Media development in Denmark—Internet use and social media in 2021]. https://mediernesudvikling.kum.dk/2021/internetbrug-og-sociale-medier/

- Naslund, J. A., Bondre, A., Torous, J., & Aschbrenner, K. A. (2020). Social media and mental health: Benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 5(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00134-x

- O’Reilly, M. (2020). Social media and adolescent mental health: The good, the bad and the ugly. Journal of Mental Health, 29(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1714007

- O’Reilly, M., Levine, D., Donoso, V., Voice, L., Hughes, J., & Dogra, N. (2022). Exploring the potentially positive interaction between social media and mental health; the perspectives of adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(2), 668–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221106573

- Parry, D. A., Davidson, B. I., Sewall, C. J. R., Fisher, J. T., Mieczkowski, H., & Quintana, D. S. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(11), 1535–1547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01117-5

- Parry, D. A., Fisher, J. T., Mieczkowski, H., Sewall, C. J. R., & Davidson, B. I. (2022). Social media and well-being: A methodological perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.005

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US Young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.013

- Rehm, J., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

- Rod, N. H., Andersen, T. O., Severinsen, E. R., Sejling, C., Dissing, A. S., Pham, V. T., Nygaard, M., Schmidt, L. K. H., Drews, H. J., Varga, T. V., Freiesleben, N., Nielsen, H. S., & Jensen, A. K. (2023). Cohort profile: The SmartSleep Study, Denmark Triangulation of evidence from survey, clinical and tracking data. BMJ Open, 13(10), e063588. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063588

- Royal Society for Public Health. (2017). #StatusofMind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing (Royal Society for Public Health & Young Health Movement). https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/campaigns/status-of-mind.html

- Rus, H. M., & Tiemensma, J. (2017). Social media under the skin: Facebook use after acute stress impairs cortisol recovery. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01609

- Schønning, V., Hjetland, G. J., Aarø, L. E., & Skogen, J. C. (2020). Social media use and mental health and well-being among adolescents – A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1949–1949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01949

- Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(4), e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842

- Shannon, H., Bush, K., Villeneuve, P. J., Hellemans, K. G., & Guimond, S. (2022). Problematic social media use in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 9(4), e33450. https://doi.org/10.2196/33450

- Sharma, M. K., John, N., & Sahu, M. (2020). Influence of social media on mental health: A systematic review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(5), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000631

- Statista. (2022a). Daily time spent on social networking by internet users worldwide from 2012 to 2022 (in minutes). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/

- Statista. (2022b). Number of social media users worldwide from 2018 to 2027 (in billions). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/

- Tromholt, M. (2016). The facebook experiment: Quitting facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(11), 661–666. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0259

- Turel, O., Cavagnaro, D. R., & Meshi, D. (2018). Short abstinence from online social networking sites reduces perceived stress, especially in excessive users. Psychiatry Research, 270, 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.017

- Valkenburg, P. M. (2022). Social media use and well-being: What we know and what we need to know. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.006

- Valkenburg, P., Beyens, I., Meier, A., & Abeele, M. (2022). Advancing our understanding of the associations between social media use and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101357

- Vanman, E. J., Baker, R., & Tobin, S. J. (2018). The burden of online friends: The effects of giving up Facebook on stress and well-being. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1453467

- Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., Ybarra, O., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 144(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057

- Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

- Warrender, D., & Milne, R. (2020). How use of social media and social comparison affect mental health. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/mental-health/how-use-of-social-media-and-social-comparison-affect-mental-health-24-02-2020/

- Wolfers, L. N., & Utz, S. (2022). Social media use, stress, and coping. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101305

- Wolfers, L., Festl, R., & Utz, S. (2020). Do smartphones and social network sites become more important when experiencing stress? Results from longitudinal data. Computers in Human Behavior, 109, 106339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106339