Abstract

Background

Priority setting in mental health research is arguably lost in translation. Decades of effort has led to persistent repetition in what the research priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health are.

Aim

This was a narrative review and synthesis of published literature reporting mental health research priorities (2011-2023).

Methods

A narrative framework was established with the questions: (1) who has been involved in priority setting? With whom have priorities been set? Which priorities have been established and for whom? What progress has been made? And, whose priorities are being progressed?

Results

Seven papers were identified. Two were Australian, one Welsh, one English, one was from Chile and another Brazilian and one reported on a European exercise across 28 countries (ROAMER). Hundreds of priorities were listed in all exercises. Prioritisation mostly occured from survey rankings and/or workshops (using dots, or post-it note voting). Most were dominated by clinicians, academics and government rather than people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer, family and kinship group members.

Conclusion

One lived-experience research led survey was identified. Few studies reported lived-experience design and development involvement. Five of the seven papers reported responses, but no further progress on priorities being met was reported.

PRISMA/PROSPERO STATEMENT

This review followed PRISMA guidance for search strategy development and systematic review and reporting. This was not a systematic review with or without meta-analysis and the method did not fit for registration with PROSPERO.

Introduction

Universities, policy makers, and philanthropic funders recognise the central place of people who live with mental ill-health and carer, family, kinship group members (referred to in this paper as people with lived-experience and within the wider literature as patient partners, consumers, carers, service users or experts by experience) in setting mental health research priorities for translation agendas (Banfield et al., Citation2018; Wykes et al., Citation2015). Despite this recognition, priority setting has largely focused on reaching expert consensus across different stakeholder groups using (Jorm, Citation2015) Delphi methods (Jorm, Citation2015), nominal group techniques (NGT) or the James Lind Alliance partnerships for priority setting (PPS) (Staley et al., Citation2020). Each has its merits, but as Hall et al. noted, “both the Delphi and NGT consensus methods are vehicles that translate knowledge derived from research evidence into practice and maximise this rigour through participant anonymity, iteration of ratings, controlled feedback and statistical evaluation of consensus” (Hall et al., Citation2021). These processes of iteration, controlled feedback and statistical evaluation guide the development of shortlisted priorities. These priorities are then reflected back into academic language and dominant stakeholder lens’ to the point that the salient meanings of the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer, family and kinship members simply become lost in translation (Rose, Citation2022).

An example of this is the commonly repeated priority area of “medication” where priorities are usually re-cast in final lists as agreement for medication effectiveness studies or more research on medication responsiveness (Elfeddali et al., Citation2014) This framing unfortunately can overlook what people with lived-experience and/or carers, family and kinship group members have shared as research priorities. These priorities span research to explore experiences of taking medication, or develop decision guides to support whether to take medications, or to examine the different gendered impacts of medication, and how to reduce side-effects (Banfield et al., Citation2018; Robotham et al., Citation2016). Yet, what is funded remains focused on effectiveness and treatment. Consequently, there’s a continued mismatch between what the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer, families and kinship group members are, and what is reported.

A contributing factor is that research investment by governments and other funding bodies is mostly based on prevalence data, and the indicators of burden of disease (Christensen et al., Citation2013; Sharan et al., Citation2009). In priority setting where researchers and funders draw on pre-existing research knowledge, or pre-established research questions often mis-alignment results (Banfield et al., Citation2011). This mis-alignment is apparent across mental health research settings. For example, clear criteria exist for involving people with lived-experience in grant applications, but the extent to which funded research grants do in fact meet the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carers, families and kinship groups, is unknown. A review of public patient involvement papers in the United Kingdom over a decade ago (2012) found that only 10% of mental health research had involved the public in identification and prioritisation of research, and fewer than 20% of researchers had consulted with people with lived-experience of mental ill-health in proposals (Ghisoni et al., Citation2017).

If the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and the needs of carers, families and kinship groups were driving funding and research, less bio-neurological and psychological-focussed research topics would dominate (as they currently do) in medical, public health, health services research and mental health translation research funding streams (Christensen et al., Citation2013). Instead, quality of care, improvements in mental health service delivery attending to social issues and social determinants, peer (lived-experience) models of care and improving experiences of care would be funded (Banfield et al., Citation2014). The social determinants of health would be embedded within models of care and intersecting issues of violence, abuse and poverty and, trauma-violence informed care (Banfield et al., Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2018; Gulliver et al., Citation2022). For the most part, there is somewhat of a chasm between mental health research funding agendas and meeting the research priorities of people living with mental ill-health and/or from carers, families and kinship group members despite priority setting efforts (Banfield et al., Citation2018; Rose, Citation2022; Wykes et al., Citation2015). It also unclear what research, policy and practice responses and progress has been made in meeting established priorities (Staley et al., Citation2020).

Adopting community-led approaches to lived-experience where people living with the topic/s at-hand (such as trauma, mental ill-health or being a carer, family or kinship group member) are centred has become critical in mental health reform, service delivery and policy setting. In community-led lived-experience approaches there is an acknowledgement of diverse expertise and differences in experiential knowledge bases brought to a topic but an openness for communities to shape what lived-experience means. These experiential knowledge bases need to be equally valued alongside what is valued in the hierarchy of evidence as knowledge derived from randomised designs or systematic reviews (Jorm, Citation2015; Palmer et al., Citation2019). It has become clear that to fully centre those most impacted (people with lived-experience) in priority setting and establishing research priorities may require different approaches than current consensus methods (Waddingham, Citation2021).

To establish the picture on what the mental health research priorities have been over the past decade, a narrative review and synthesis of literature published since 2011 was undertaken. The review formed part of the blueprint activities for the co-design of a national roadmap for Australia’s first focused Mental Health Research Translation Centre (called the ‘ALIVE National Centre’ herein). The ALIVE National Centre was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) as part of a special initiative in mental health (2021–2026). The blueprint was developed in 2021 and activities continued over 2022 (see http://www.alivenetwork.com.au) and included: this current narrative review and synthesis; a national policy scan; ecosystem mapping to establish a picture on place-based initiatives relevant to the Centre’s research objectives of prevention across the life course, unmet physical health needs in priority populations and lived-experience led research and delivery of mental health care at-scale; a national (and annual) co-partnered lived-experience priorities survey to continuously gather and update priorities, and prioritisation (using public co-design methods) with people with lived-experience and carers, family and kinship group members to co-create phased Consensus Statements on implementation actions for priority areas. This forms a dynamic, living national roadmap for mental health research translation. A co-design process is underway by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers to establish First Nations community-led priorities pathways within the roadmap. With multiple pathways of priority populations planned. The ALIVE National Centre’s Roadmap will be implemented over the duration of the Centre funding (2021–2026) and an impact evaluation will review annual progress within priorities subsequently updated in the national Roadmap.

Methods

The narrative review and synthesis used the five interrogative pronouns of who, whom, which, what and whose to establish the review and synthesis questions, as follows (Palmer et al., Citation2011): (1) who has been involved in priority setting? With whom have priorities been set? Which priorities have been established and for whom? What progress has been made? And, whose priorities are being progressed (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2018)?

Search Strategy

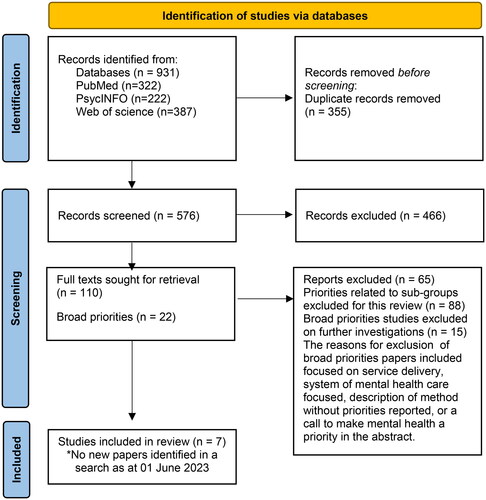

The PRISMA statement for reporting was used to present the search results (see ) (Page et al., Citation2021). Searches focused on core concepts of (priority-setting AND research) AND (mental health) as outlined in Box 1.

Priority-setting was restricted to the title field to avoid the identification of papers that mentioned a future research agenda being a priority in the conclusion to the abstract. The searches were conducted in September 2022 and updated in August 2023 (no new papers were found). Searches in PsycINFO (Ovid) and Web of Science included the same terms with search functions and subject headings tailored for each engine.

Study selection

Four authors reviewed the papers. Of the author team, three co-authors hold lived-experience research roles, one author is a First Nations Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researcher, the remainder cross disciplines of applied ethics, participatory design, pharmacy, neuroscience, primary care and family violence and two identify as having lived-experience of mental ill-health but do not hold lived-experience focused only research positions. The papers were all reviewed and grouped into two categories. Category 1 papers—the focus of this narrative review and synthesis—reported on priority identification, priority setting or prioritisation exercises to establish consensus for mental health research broadly. Category 2 papers—not the focus of this current review and synthesis—reported on the priority identification, priority setting or prioritisation to establish consensus within what we termed sub-groups (explained in the next section).

Box 1. Search strategy and results.

Exclusion criteria

Sub-group papers were those where priority setting was specific to single conditions or issues such as priorities in suicide prevention research, depression research, or bipolar disorder, children and young people and adolescent mental health, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health research priorities. Those sub-group studies were excluded and a meta-narrative review and synthesis of priorities within subgroups is underway. Papers describing research agendas based on literature/evidence or document reviews without any further priority setting exercises completed were excluded. Papers reporting on individual components of a larger reported priority setting exercise were excluded (for example, multiple sub-papers reported on different survey development and outcomes for the final ROAMER roadmap and its final report). The PRISMA flowchart in shows the study selection processes for the seven papers that met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Identified articles were exported from each individual database to EndNote20 and duplicates were removed, notes regarding decisions were retained in the endnote library (Team, Citation2013). Article titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility and sorted into Category 1 or 2. Uncertainty or disagreements, were resolved by co-author discussions. The narrative review and synthesis framework guided the data extraction for the Table (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2005). No quality appraisal tool was applied with the vast heterogeneity of the study sizes, methods used, and reporting on prioritisation and priorities.

Narrative review

After excluding 355 duplicates, 576 papers were identified for screening. Of this 466 were excluded and 110 full text articles were reviewed further. Twenty-two of the 110 were deemed to be Category 1 papers, on closer review however 15 were excluded for the reasons outlined in . A final set of seven papers was included.

Two of the final seven papers were Australian studies with one that elicited consumer and carer mental health research priorities (Banfield et al., Citation2018) and the other establishing consensus on research priorities for a research partnership between a university and service organisation in one region of Australia, the Sunshine Coast area of Queensland (McAllister et al., Citation2012). A Welsh paper reported on priority setting as part of a Service User and Carer Partnership supported by the National Centre for Mental Health Care Research in Wales and Hafal, (Ghisoni et al., Citation2017) and a fourth paper outlined research priorities for a biomedical research centre in England (Robotham et al., Citation2016). Two South American studies one Chilean (Zitko et al., Citation2017) and another Brazilian (Gregório et al., Citation2012) established priorities to facilitate links between research and policy. One paper was from the ROAMER priority setting exercise for Europe across 28 different countries (Wykes et al., Citation2015). Three additional ROAMER papers were excluded (Elfeddali et al., Citation2014; Fiorillo et al., Citation2013; Haro et al., Citation2014) because these reported on individual stakeholder exercises and the results were already included within the larger ROAMER paper.

All papers reported on the prioritisation methods used. Surveys (usually established by researchers using priorities from the literature) were common and voting on the priorities in workshops (n = 3). Focus group discussions (reported as modified Nominal Group Techniques and/or Delphi’s) (n = 2) were reported and online surveys for either establishing topics, or scoring to rank priorities or questions (n = 3). Literature/document analysis (n = 2) and interviews (n = 1) were employed. The papers by Banfield and Ghisoni et al. both reported workshop discussions and voting methods for prioritisation and in Banfield et al. a national, open-ended survey was used. Two of the seven papers worked with people with lived-experience only to set priorities, three included people with lived-experience in stakeholder groups and two appeared to report no involvement at all. plots the narrative review results. Where any impacts from priority settings or release of priorities were documented, these were noted in also.

Table 1. Narrative review and synthesis of the priorities in mental health research and/or mental health research translation.

details the priorities established in all studies. Banfield et al., established 79 priority research areas with 14 broad thematic areas that informed a second study to update the group’s research agenda and extend participation through a national online survey in 2017 (n = 70). Importantly, the authors concluded that there was no clear consensus on priorities for consumers and/or carers. The continued themes of service delivery, training of staff in mental health (particularly General Practitioners), and service quality were important. Survey participants said the appropriateness of diagnosis and care delivered, gaps in services, and the negative consequences of compulsory treatment were priorities. Involvement of people with lived-experience in the research itself was also a priority as was over representation of people with mental ill-health in the justice system. Banfield et al., also noted differences between the priorities of groups. Consumers in study 1 voted for research into peer-led services, and recovery and fulfilling potential, the effects of stigma, human rights and legislation and learned helplessness in response to experiences of services, whereas carers’ research priorities coalesced around interactions with health care professionals, the carer experience, and the influences of privacy on care including the effects of drug and alcohol use. In Study 2 consumers consistently prioritised the implementation of peer services, while carers prioritised carer support, service reach and continuity of care and support for suicide. For people identifying as both a consumer and carer, the coordination of care, planning and carer recovery were important.

Ghisoni et al reported 120 priorities and research ideas that were shared by 25 people (Ghisoni et al., Citation2017). Thirty-three themed areas were noted and most linked with treatment and recovery, mental health recovery, law and access to services including crisis prevention and other treatments. People said information still lagged on how to get the best from services, improvements in access to education and higher education as well as education for mental health recovery and making this available to the public and local community were noted. Training, education and resourcing for the public (particularly young people and the media) were identified as priorities to combat stigma, labels and attitudes, and discrimination. Partnership work was said to be key to effective crisis identification and for crisis support. The importance of partnership approaches (including the person living with mental ill-health, carer, family supports and professionals) peer mentors and promotion of how the community can play a role in crisis support were noted. An additional priority for carers (due to limited numbers in the voting process) was added as, ‘how can carers take up the reins of their own life as the person they care for is in recovery?’

Workshop participants in Ghisoni’s study also explored what support services might look like if they were therapeutic and recovery focused, and how to support people to return to work. Balancing the therapeutic effects of work and the expectations of others, alongside having an ambassador model to support the transition back to work were prioritised. Additional themes (based on any topic not covered in the previous five workstations) included access to research (opportunities and findings), being more involved in research, support and resources available for being engaged in the development of mental health services and, the education and training needs of children and young people in school. Ghisoni et al. concluded also that people with lived-experience of mental ill-health can and do generate and prioritise areas of research differently from health professionals.

Zitko et al used a multi-method approach to identify gaps in mental health research and to prioritise research questions to guide policy and investment decisions in Chile (Zitko et al., Citation2017). Document analyses and key informant interviews followed by a survey were used to prioritise the 155 research questions for health policy decision-making. Respondents addressed the “extent of the knowledge gap, size of the objective population, potential benefit, vulnerability, urgency, and applicability”. Common knowledge gaps were identified in ‘Evaluation of Systems and/or Health Programs’ (44% of questions), followed by ‘Evaluation of Interventions including cost-effectiveness’ (26% of questions), ‘History of Disease, Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Social Determinants’ (18%), and finally ‘Evaluation of Intersectoral Public Policies’ (11%). While Ministry of Health officials prioritised the ‘Evaluation of Systems and/or Health Programs’ and the performance of human resources in primary health care in the detection and management of people with mental disorders (scoring 83.3/100), National Health Strategy reviews identified that determining factors of the variability of the comprehensive mental health care program, between primary care centres (scoring 83.3/100) was key.

The top scoring gap in Zitko et al’s., a study from mental health service users (third highest listed overall) was to determine factors of the unchanging and unequal geographic distribution of resources of specialised mental health human resources (scoring 75.0/100). ‘Evaluation of Interventions’ identified the cost-effectiveness of the psychosocial activities in municipal, educational and work settings in the general population (scoring 66.7/100) as important with the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of evidence-based interventions to prevent adolescent suicide (66.7). The ‘Natural History of Disease/Epidemiology/Risk Factors/Social Determinants’ identified priorities for the prevalence of mental disorders in minority populations (scoring 70.0/100), and transgenerational factors associated with intrafamilial child sexual abuse (scoring 66.7/100). Relatively small numbers of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health (including carer, family and kinship groups) were engaged. A mental health specific research funding round did result from the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (2014), but ongoing progress was not reported.

In contrast to Zitko’s use of documents, key informant interviews and a survey, Robotham et al held a service user workshop to inform the research centre agenda and strategy. Robotham et al’s rationale was that service users and clinician priorities have been different and in conflict (also noted in Ghisoni and Banfield’s studies). For research priorities and questions, service users said that recognition of early warning signs prior to a crisis, increasing mental health awareness in young people, and acting earlier before severity increases for diagnosis and intervention were priorities. Service users also felt maintenance of medication to reduce burdens (support cessation of management), and exploration of the long-term effects of polypharmacy and its production of reversible or irreversible side effects and how medication review processes might be conducted were important. In particular, service users noted that “side effects profiles vary, so more information is needed about what works for individuals, rather than what works for people ‘‘in general” (Robotham et al., Citation2016).

Robotham et al., also noted the impact of poor physical health on mental health (and vice versa) and identifying the effects of nutrition, alcohol and exercise on mental health and wellbeing. Socio-environmental factors like financial insecurity on mental ill-health, or contribution support networks, and peer support were prioritised. For new therapies and interventions, complementary therapies and mindfulness and examining how relationships between primary and secondary care can be managed and how Big Data can be used to provide solutions and insights were all important.

The extensive ROAMER priority setting exercise (Wykes et al., Citation2015) to promote and integrate mental health research across 28 countries of the European Union led to priority areas being established to guide mental health research for 2015–2025. The five research priority areas were: supporting mental health for all; responding to social values and issues; life course perspectives on mental health issues; research toward personalised care; and, building research capacity. Policy actions included: funding long-term prospective cohort studies on the determinants of mental health and wellbeing for identification of risk and protective factors for prevention and mental health promotion; adopting mental health promotion and social exclusion prevention in schools to develop pharmacological and psychological treatments for children and adolescents; examining if prevention of maternal depression in pregnancy leads to protective factors for children for future ill-health and what the costs benefits are; longitudinal studies to analyse the effects of intense new forms of media (the internet, gaming and social media) in early age and adolescence on later emotional and cognitive competence. For development and causal mechanisms the actions included: identifying factors that underly comorbidity and multimorbidity; and extended research on single disorders to typical comorbid constellations; defining the functional characteristics of neuro-behavioural mechanisms across the lifespan; and the identification of social and biological factors that underlie risk or resilience factors for mental disorders across the lifespan.

Additional key actions included the effects of financial crises on mental health and understanding how vulnerabilities and stress affect critical developmental trajectories for poor health and specific mental disorders across the lifespan (particularly in childhood and adolescence). Prediction from brain abnormalities of future mental disorders using longitudinal structural and functional neuroimaging was another policy action. Development and maintenance of international and interdisciplinary networks and shared databases actions included: increasing the number, quality and efficiency of international and interdisciplinary networks, developing multidisciplinary training programs for mental health across different countries, implementation of standardised European research outcomes, databases and terminology for mental health and wellbeing research; and, establishing access to European mental health databases across different studies with standardised mental health outcomes.

Further actions were from ROAMER to strengthen research into new approaches and technology for mental health promotion, disorder prevention, mental health care and social service delivery was seen to improve interventions using new scientific and technological advances. Testing the value of internet-based treatments as automated versions of standard psychological treatments in specialised mental health care within indicated prevention, and particularly the use of this in primary care settings plus test real-time psychometric feedback over the course of treatment (supported by modern software) to adapt dosage and intensity of treatment to service users’ complexity and problem profile to promote better outcomes were action areas.

Other priority actions were about the examination of the acceptability and adherence of eHealth treatments, clinical improvement at 1-year follow-up and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in comparison with conventional psychological therapies. Exploring why some individuals do not respond to treatment by identification of relevant, and potentially developmental-phase-specific, mediating and moderating variables of evidence-based psychotherapies for youths with mental disorders were other actions. To reduce stigma and empower service users and carers in decisions about mental health research the following actions were noted: studying how carers and family members of people with mental health problems might perceive and experience stigma by association; identifying the best methods to measure and value unpaid care; pinpointing the most cost-effective elements of anti-stigma interventions; studying the role of stigma in the wider context of inequalities (for example, health inequalities) and implementation of interventions to assess and change the role of stigma in access to public services; and, establishing better national or local interventions to address stigma, social exclusion, and discrimination by a careful definition of the essential questions (for example, who should be targeted; how, by whom, and when should targeting be done) and to determine how and by whom people may be assessed.

Additional areas included investigations into how to establish health-systems and social-systems research that address quality of care with sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts and that account for the effect of differences in the organisation and delivery of national health-care systems on the wellbeing of individuals with mental disorders and their carers. Final action areas included studying at the health-systems level, the cost-effectiveness of different ways to finance, regulate, organise, and provide services that promote and protect mental health, and designing and investigating methods to assess outcomes from mental health services that can be easily and reliably implemented.

While ROAMER examined mental health research priorities across 28 countries with similar health service structures, McAllister et al. reported a defined set of mental health research priorities specific to an Australia region to improve mental health services. details the top three research priorities generated from a single question asking people ‘what are the top priority research ideas you have for the Sunshine Coast Health Service District Mental Health Service?’ When data from all cohorts was combined emotional well-being was the top research priority area. The second priority area was service quality and accountability (highest for consumers, lowest for clinicians) and family involvement in the care of relatives and consumer involvement in their own personal care. McAllister et al. set out four recommendations for service delivery as documented in . The extent to which these priorities have been implemented was not documented, nor was it clear if consumers and/or carers were engaged in the analysis of the priorities and the development of the recommendations.

Gregorio et al reviewed mental health research priorities for the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Gregório et al., Citation2012). A working group involved 28 experts (22 researchers, 5 policy makers, and the study coordinator) but did not appear to include any people with lived-experience of mental ill-health or carers, families or kinship group members. Priority setting was undertaken using the Child and Nutrition Research Initiative (CNRI) methodology (Rudan et al., Citation2008) used for a global metal health research priority setting exercise previously (Tomlinson et al., Citation2009). The experts (including psychiatrists and experts in addiction and primary care) generated 110 mental health research questions across five allocated domains. Scoring determined the most significant 35 questions (these were said to be reported in an unavailable Appendix).

Four of the top ten priorities from Gregorio et al’s., study were related to the identification and treatment of common mental disorders in primary care: (intervention effectiveness, models of stepped care, ‘matrix support’ and interventions to enhance and treat common mental disorders in primary care). The other top 10 questions related to the cost-effectiveness of psychotropic medicines, effective policies/interventions for managing alcohol and drug consumption, telemedicine for education/supervision of non-specialists, barriers to treatment access for serious mental illness and addiction, and effectiveness and coverage of psychosocial community centres. The Brazilian Ministry of Health focused on the following priorities to implement primary-care level interventions to ‘reduce the burden of illness’ and ‘improve quality of life for people experiencing mental ill-health and alcohol and other drug use’. No further details of how priorities were responded to or the impacts were provided.

Narrative synthesis

Priority setting in mental health research has continued over decades (Banfield et al., Citation2011; Banfield et al., Citation2018; Collins et al., Citation2011; Jorm, Citation2015; Rose et al., Citation2008; Sharan et al., Citation2009; Tomlinson et al., Citation2009). Yet, there is a lag between when priorities are set, and when these are published for the wider research community, policy makers, service planners, providers and funders. Consensus building efforts—despite good intentions—have resulted priorities becoming shorthand statements that largely reflect those of stakeholders than those of the people most impacted (people with lived-experience of mental ill-health). The priorities of people with lived-experience have become lost in translation. Consistent themes emerge and re-emerge in priority exercises: service delivery, treatment experiences, recovery journeys, self-management, receiving trauma-informed care, and safety of services, welcoming places, and acknowledging the impacts of service system harms and structural violence for people and how they might engage with services and the kinds of models of care people are looking for. While low and middle income countries have contextual differences in what is prioritised for example effectiveness of treatment, or resource allocation, there are similar patterns (Gregório et al., Citation2012). Although ROAMER and two South American studies had follow on funding calls as a result of the priority setting, there has been little to no tracking and monitoring of the impacts over time. Progress in meeting people with lived-experience’s research priorities has, it seems, been limited.

One possible reason may be that we need a methodological turn is needed in priority setting and to privilege the priorities for mental health research for those most impacted (e.g. people with lived-experience) rather than focusing on consensus across clinician, government and other stakeholder groups. In Australia, two national surveys have started this process with a lived-experience research team leading one and representing 70% of team members in the other (Banfield et al., Citation2011; Banfield et al., Citation2018; Banfield et al., Citation2014). Since people with lived-experience tend not to express a desire for a top-three priority list, and the priorities between groups, such as between consumers to carers can and do differ – as they do with clinicians and policy makers, diversification of methods is needed (Banfield et al., Citation2018; Ghisoni et al., Citation2017; Robotham et al., Citation2016). It will be important to identify if these patterns persist in the research priority setting exercises that have been undertaken for specific sub-groups such as for suicide prevention (Niner et al., Citation2009; Robinson & Pirkis, Citation2014; Robinson et al., Citation2008) for mental health services (Mihalopoulos et al., Citation2013) and eating disorders;(Hart & Wade, Citation2020; Wade et al., Citation2021) and priorities for policy for youth mental health (Rickwood, Citation2011).

The common message within all priority work is that investment in mental health research must be expanded. Christensen et al. reviewed Australian funding and research priorities published in 2013 for the decade prior to this narrative review and synthesis period (2003–2013) and determined that the priorities for depression and suicide prevention had been under researched. Prevention and promotion, and psychological and social interventions and service evaluations and, neglect of community and primary care research settings were common themes (Woelbert et al., Citation2021). While an international increase in suicide prevention research and prevention initiatives has been apparent, the areas of primary care, community-led innovations and lived-experience (peer) designed and implemented models of care have continued to be underrepresented and neglected (Christensen et al., Citation2013). The prioritisation of social models is not new and has been favoured in the past. A 2007 study by Rose and Wykes showed social models as preferred (Rose et al., Citation2008) yet, psy-based (psychology and psychiatry models) continue to dominate. The investments in mental health research do not match those in physical health research (referred to in the literature as the 10/90 gap) (Sharan et al., Citation2009) Research and translation efforts therefore need to be reoriented (Lewis-Fernández et al., Citation2016). The first mental health priority setting exercises in low and middle income countries in 2009 identified that epidemiological research was one of the top three consensus areas. What is often overlooked is that this was alongside health services research and social science research, which have not received anywhere near the levels of funding (Sharan et al., Citation2009).

Centring the priorities of those most impacted is an objective of the ALIVE National Centre’s co-partnered annual and national Lived-Experience Priority Setting survey. In 2022 there were 365 people with lived-experience of mental ill-health who contributed research priorities which represents the largest national survey to date. This has led to the development of a publicly available database of priorities for mental health research across the life course for researchers to access in an attempt to better respond.

Limitations

This narrative review and synthesis did not incorporate the priorities established in sub-group exercises in broader mental health research fields (as this is the focus of a larger meta-narrative review) nor was it possible to take a life course approach. This makes it difficult to establish if sub-group priorities differ or if the priorities of children to adolescents and younger people, to young adults, adults and older adults differ and how. The review was restricted also to published academic papers. It is possible that grey literature and reports exist on relevant or overlapping priority setting at service levels or for smaller localised government exercises.

Conclusion

The story of mental health research and/or translation priority setting, and prioritisation is in many ways a narrative that reflects the challenges of shifting systemically engrained biases, structural injustices and inequities in mental health care delivery. Social models of care and peer-based approaches have consistently been reported as priorities, however, most mental health care funding supports models that override these. Consensus efforts may have unintentionally masked the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer, family, kinship groups in the focus on agreement across groups. Finally, limited evaluation has been conducted into the impacts of priority setting and what has ensued in research and policy. The ALIVE National Centre for mental health research translation provides a unique opportunity to establish a national and coordinated approach to mental health research priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carers, family kinship groups at-scale with the international application. The co-designed roadmap provides the translational pathway to establish the implementation actions that are needed centred on people with lived-experience and carer, family and kinship group priorities across the life course. This means we must shift consensus to being about the priorities of those most impacted instead of across stakeholder groups where priorities are being lost in translation.

Authors contributions

VP and MB conceived the need for the narrative review and synthesis. VP designed a narrative review framework for analysis and synthesis, and VP and MB established the search strategy with AG, KH and AW. AG completed the preliminary search and saved the searches to endnote. AG organised the data set for review and completed the PRISMA reporting flowchart with DJ. VP, AG, MB and DJ screened the titles and abstracts to identify eligible papers for inclusion. Full papers were discussed in regular team meetings with all named authors including PO bringing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research perspective and JM who provided further lived-experience contributions to data interpretation. AW presented the preliminary findings of the narrative review and synthesis at the ALIVE National Annual Symposium 2022 held in Hobart Tasmania, Australia supported by VP and DJ in preparation of this. VP led the drafting, editing and final review of this manuscript. All named authors have read, edited and approved this version for submission. The ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation investigators have been provided an opportunity to read and approve this version for submission under the Centre’s agreement across university partner organisations. The authors are accountable for the research presented in the paper and its quality and integrity.

Authors information

VP is a humanities and arts based scholar located within a Medical Faculty who trained in narrative theory, applied ethics, and who has worked in primary care mental health research and participatory design, and co-design for 15 years. AW is a pharmacist and applied clinician researcher exploring severe mental ill-health and medication management by pharmacists. DJ holds a PhD in neuroscience. AG is a lived-experience researcher with over ten years experience in mental health research. KH is a family violence international expert, who developed the composite abuse scale with research expertise across quantitative and qualitative study designs and intimate partner violence, trauma-violence informed research and practice. JM is an emerging lived-experience and co-design researcher who brings this perspective to the role and who applies a lived-experience lens in his research and practice activities. PO is an Aboriginal Muruwori Gumbaynigrri man, who leads First Nations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander co-design within the ALIVE National Centre and MB is a lived-experience researcher with over 17 years experience working on consumer and carer priorities within the Australian context.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the contributions of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer/family kinship group members to the datasets presented by co-author M Banfield for consumer and carer mental health research priorities over the past decade. The authors also acknowledge the priority setting conducted by the Co-Design Living Labs program members at the University of Melbourne for the establishment of the funding proposal for the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation. The Co-Design Living Labs program includes nearly 2000 people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer, family and kinship group members who are engaged in end to end research design translation model. More than 115 people from the Co-Design Living Labs program established the priorities for the ALIVE National Centre vision and co-designed ideal journeys through the Centre and its programs. The authors thank co-investigator on the ALIVE National Centre Associate Professor Amanda Neil for their review and feedback on the paper and research support provided in the early stages toward the first rounds of screening by Richard Violette at Griffith University.

Collaborating Author Names for the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation Investigator Group include: Victoria J Palmer, The University of Melbourne Australia; Michelle A Banfield, The Australian National University, Australia; Sandra Eades, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Jane M Gunn, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Jane Pirkis, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Nicola Reavley, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Steve Kisely, The University of Queensland, Australia; David Preen, University of Western Australia; Amanda Neil, University of Tasmania, Australia; Amanda Wheeler, Griffith University; Harriet Hiscock, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Royal Children’s Hospital; Emma Baker University of Adelaide, Australia; Cherrie Galletly University of Adelaide, Australia; Christos Pantelis University of Melbourne, Australia; Darryl Mayberry, Monash University, Australia; Nicola Lautenschlager, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Osvaldo Almeida, University of Western Australia; Lena Sanci, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Sarah Larkins James Cook University, Australia; Michael Wright Curtin University, Australia; Vera Morgan, University of Western, Australia; Lisa Brophy La Trobe University, Australia; Kelsey Hegarty, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Meredith Harris, The University of Queensland, Australia; Jim Lagopoulos, University of Sunshine, Australia; Wendy Chapman, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Carol Harvey, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Jenny Bowman, University of Newcastle, Australia; Michelle Lim, University of Sydney, Australia; David Coghill, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Bridget Hamilton, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Jill Bennett, University of New South Wales, Australia; Meaghan O’Donnell, The University of Melbourne, Australia; Luke Burchill, Mayo Clinic, United States and The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Banfield, M. A., Barney, L. J., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. M. (2014). Australian mental health consumers’ priorities for research: qualitative findings from the SCOPE for Research project. Health Expectations, 17(3), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00763.x

- Banfield, M., Griffiths, K., Christensen, H., & Barney, L. (2011). SCOPE for research: Mental health consumers’ priorities for research compared with recent research in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(12), 1078–1085. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.624084

- Banfield, M., Morse, A., Gulliver, A., & Griffiths, K. (2018). Mental health research priorities in Australia: a consumer and carer agenda. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0395-9

- Christensen, H., Batterham, P. J., Griffiths, K. M., Gosling, J., & Hehir, K. K. (2013). Research priorities in mental health. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412474072

- Collins, P. Y., Patel, V., Joestl, S. S., March, D., Insel, T. R., Daar, A. S., Anderson, W., Dhansay, M. A., Phillips, A., Shurin, S., Walport, M., Ewart, W., Savill, S. J., Bordin, I. A., Costello, E. J., Durkin, M., Fairburn, C., Glass, R. I., Hall, W., … Stein, D. J. (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature, 475(7354), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/475027a

- Elfeddali, I., Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., Van Os, J., Knappe, S., Vieta, E., Wittchen, H. U., Obradors-Tarragó, C., & Haro, J. M. (2014). Horizon 2020 priorities in clinical mental health research: Results of a consensus-based ROAMER expert survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10915–10939. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/11/10/10915 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010915

- Fiorillo, A., Luciano, M., Del Vecchio, V., Sampogna, G., Obradors-Tarragó, C., & Maj, M. (2013). Priorities for mental health research in Europe: a survey among national stakeholders’ associations within the ROAMER project. World Psychiatry, 12(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20052

- Ghisoni, M., Wilson, C. A., Morgan, K., Edwards, B., Simon, N., Langley, E., Rees, H., Wells, A., Tyson, P. J., Thomas, P., Meudell, A., Kitt, F., Mitchell, B., Bowen, A., & Celia, J. (2017). Priority setting in research: User led mental health research. Research Involvement and Engagement, 3(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0054-7

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O., & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 61(2), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001

- Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 48(6), e12931. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12931

- Gregório, G., Tomlinson, M., Gerolin, J., Kieling, C., Moreira, H. C., Razzouk, D., & Mari, J. D J. (2012). Setting priorities for mental health research in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 34(4), 434–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbp.2012.05.006

- Gulliver, A., Morse, A. R., & Banfield, M. (2022). Keeping the agenda current: Evolution of Australian lived experience mental health research priorities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138101

- Hall, T., Honisett, S., Paton, K., Loftus, H., Constable, L., & Hiscock, H. (2021). Prioritising interventions for preventing mental health problems for children experiencing adversity: A modified nominal group technique Australian consensus study. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00652-0

- Haro, J. M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Bitter, I., Demotes-Mainard, J., Leboyer, M., Lewis, S. W., Linszen, D., Maj, M., McDaid, D., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Robbins, T. W., Schumann, G., Thornicroft, G., Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C., Van Os, J., Wahlbeck, K., Wittchen, H.-U., Wykes, T., Arango, C., … Walker-Tilley, T. (2014). ROAMER: roadmap for mental health research in Europe. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(Suppl 1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1406

- Hart, L. M., & Wade, T. (2020). Identifying research priorities in eating disorders: A Delphi study building consensus across clinicians, researchers, consumers, and carers in Australia. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23172

- Jorm, A. F. (2015). Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(10), 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415600891

- Lewis-Fernández, R., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Betts, V. T., Greenman, L., Essock, S. M., Escobar, J. I., Barch, D., Hogan, M. F., Areán, P. A., Druss, B. G., DiClemente, R. J., McGlashan, T. H., Jeste, D. V., Proctor, E. K., Ruiz, P., Rush, A. J., Canino, G. J., Bell, C. C., Henry, R., & Iversen, P. (2016). Rethinking funding priorities in mental health research. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(6), 507–509. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.179895

- McAllister, M., Munday, J., Taikato, M., Waterhouse, B., & Dunn, P. K. (2012). Determining mental health research priorities in a Queensland region: an inclusive and iterative approach with mental health service clinicians, consumers and carers. Advances in Mental Health, 10(3), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.2012.10.3.268

- Mihalopoulos, C., Carter, R. O. B., Pirkis, J., & Vos, T. (2013). Priority-setting for mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 22(2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.745189

- Niner, S., Pirkis, J., Krysinska, K., Robinson, J., Dudley, M., Schindeler, E., De Leo, D., & Warr, D. (2009). Research priorities in suicide prevention: A qualitative study of stakeholders’ views. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 8(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.8.1.48

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Palmer, V. J., Weavell, W., Callander, R., Piper, D., Richard, L., Maher, L., Boyd, H., Herrman, H., Furler, J., Gunn, J., Iedema, R., & Robert, G. (2019). The Participatory Zeitgeist: An explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and co-design in healthcare improvement. Medical Humanities, 45(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2017-011398

- Palmer, V. J., Yelland, J. S., & Taft, A. J. (2011). Ethical complexities of screening for depression and intimate partner violence (IPV) in intervention studies. BMC Public Health, 11(Suppl 5), S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S5-S3

- Rickwood, D. J. (2011). Promoting youth mental health: priorities for policy from an Australian perspective. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5(s1), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00239.x

- Robinson, J., & Pirkis, J. (2014). Research priorities in suicide prevention: an examination of Australian-based research 2007–11. Australian Health Review, 38(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH13058

- Robinson, J., Pirkis, J., Krysinska, K., Niner, S., Jorm, A. F., Dudley, M., Schindeler, E., De Leo, D., & Harrigan, S. (2008). Research priorities in suicide prevention in Australia: A comparison of current research efforts and stakeholder-identified priorities. Crisis, 29(4), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.29.4.180

- Robotham, D., Wykes, T., Rose, D., Doughty, L., Strange, S., Neale, J., & Hotopf, M. (2016). Service user and carer priorities in a biomedical research centre for mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 25(3), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2016.1167862

- Rose, D. (2022). Working with others and coproduction. In Bruce Cohen (Eds.), Mad knowledges and user led research the politics of mental health and mental illness. The Politics of Mental Health and Illness Series. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rose, D., Fleischman, P., & Wykes, T. (2008). What are mental health service users’ priorities for research in the UK? Journal of Mental Health, 17(5), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701878724

- Rudan, I., Gibson, J. L., Ameratunga, S., El Arifeen, S., Bhutta, Z. A., Black, M., Black, R. E., Brown, K. H., Campbell, H., Carneiro, I., Chan, K. Y., Chandramohan, D., Chopra, M., Cousens, S., Darmstadt, G. L., Meeks Gardner, J., Hess, S. Y., Hyder, A. A., Kapiriri, L., … & Webster, J. (2008). Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croatian Medical Journal, 49(6), 720–733. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2008.49.720

- Sharan, P., Gallo, C., Gureje, O., Lamberte, E., Mari, J. J., Mazzotti, G., Patel, V., Swartz, L., Olifson, S., Levav, I., de Francisco, A., & Saxena, S. (2009). Mental health research priorities in low- and middle-income countries of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(4), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050187

- Staley, K., Crowe, S., Crocker, J. C., Madden, M., & Greenhalgh, T. (2020). What happens after James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships? A qualitative study of contexts, processes and impacts. Research Involvement and Engagement, 6(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00210-9

- Team, T. E. (2013). EndNote: (Version Endnote 20) [64 bit]. Clarivate.

- Tomlinson, M., Rudan, I., Saxena, S., Swartz, L., Tsai, A. C., & Patel, V. (2009). Setting priorities for global mental health research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(6), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.08.054353

- Waddingham, R. (2021). Mapping the lived experience landscape in mental health. NSUN and MIND.

- Wade, T. D., Hart, L. M., Mitchison, D., & Hay, P. (2021). Driving better intervention outcomes in eating disorders: A systematic synthesis of research priority setting and the involvement of consumer input. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(3), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2759

- Woelbert, E., Lundell-Smith, K., White, R., & Kemmer, D. (2021). Accounting for mental health research funding: developing a quantitative baseline of global investments. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(3), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30469-7

- Wykes, T., Haro, J. M., Belli, S. R., Obradors-Tarragó, C., Arango, C., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Bitter, I., Brunn, M., Chevreul, K., Demotes-Mainard, J., Elfeddali, I., Evans-Lacko, S., Fiorillo, A., Forsman, A. K., Hazo, J.-B., Kuepper, R., Knappe, S., Leboyer, M., Lewis, S. W., … Wittchen, H.-U. (2015). Mental health research priorities for Europe. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00332-6

- Zitko, P., Borghero, F., Zavala, C., Markkula, N., Santelices, E., Libuy, N., & Pemjean, A. (2017). Priority setting for mental health research in Chile. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0168-9