Abstract

Background

The elimination of restrictive practices, such as seclusion and restraint, is a major aim of mental health services globally. The role of art therapy, a predominantly non-verbal mode of creative expression, is under-explored in this context. This research aimed to determine whether art therapy service provision was associated with a reduction in restrictive practices on an acute inpatient child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) unit.

Methods

The rate (events per 1,000 occupied bed days), frequency (percent of admitted care episodes with incident), duration, and number of incidents of restrictive practices occurring between July 2015 and December 2021 were analysed relative to art therapy service provision. The rate, frequency and number of incidents of intramuscular injected (IM) sedation, oral PRN (as-needed medication) use, and absconding incidents occurring in conjunction with an episode of seclusion or restraint were also analysed.

Results

The rate, frequency, duration, and total number of incidents of seclusion, the frequency and total number of incidents of physical restraint, and the rate, frequency and total number of incidents of IM sedation showed a statistically significant reduction during phases of art therapy service provision.

Conclusions

Art therapy service provision is associated with a reduction in restrictive practices in inpatient CAMHS.

Introduction

The elimination of seclusion and restraint practices is a major aim of mental health services globally (Duke et al., Citation2014; Muir-Cochrane et al., Citation2014). Incidents of seclusion and restraint are associated with an increased risk of psychological distress, trauma, humiliation, injury, and even death (Knox & Holloman, Citation2012; LeBel et al., Citation2010; Nunno et al., Citation2006; Valenkamp et al., Citation2014). Seclusion is defined as an incident wherein a person is alone in an area which they are unable to freely exit, while restraint involves physical, chemical, or mechanical restriction of a person’s freedom of movement (Bureau of Health Information, Citation2019; NSW Health, Citation2020). The World Health Organization (Citation2019) has identified that these restrictive practices constitute a human rights violation, and are considered “cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatments” (p. 28).

Furthermore, restrictive practices are associated with increased staff turnover, injury, absences, compensation claims, illness, and burnout (Bigwood & Crowe, Citation2008; Dean et al., Citation2010; LeBel & Goldstein Citation2005; LeBel et al., Citation2010). This indicates a significant impact on the wellbeing of mental health staff, who report an inadequate provision of viable alternatives to keep patients and staff safe (Bigwood & Crowe, Citation2008; Muir-Cochrane et al., Citation2018). Inversely, a reduction in restrictive practices has been correlated with shorter hospital admissions, greater sustained success in the community after discharge (LeBel et al., Citation2010), fewer patient and staff injuries, and a decrease in staff turnover (LeBel & Goldstein, Citation2005).

When examining global approaches to reducing restrictive practices in inpatient care, there has been a move away from motivational programming such as behavioural reward systems, which can be counterproductive, and potentially increase incidents of seclusion or restraint (Mohr et al., Citation2009). Instead, there has been an increased emphasis on prevention-oriented strategies to lower rates of restrictive practices in inpatient care. The literature on restrictive practices highlights the effectiveness of strategies which can improve self-regulation (Andrassy, Citation2016; Felver et al. Citation2017, Huckshorn, Citation2004; LeBel et al., Citation2004), interventions which are multimodal (Delaney, Citation2001; Gaskin et al., Citation2007; Huckshorn & LeBel, Citation2013), and those which integrate a person’s individualised interests (Caldwell et al., Citation2014).

The “Six core strategies to reduce seclusion and restraint use” developed by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors in the USA (Huckshorn, Citation2004; Huckshorn et al., Citation2005) has been widely adopted in mental health settings (Azeem et al., Citation2018; Caldwell et al., Citation2014; Wieman et al., Citation2014). The fourth core strategy outlined in this framework relates to the use of seclusion and restraint prevention tools (Huckshorn, Citation2004). This strategy emphasises awareness of a person’s trauma history, and the use of de-escalation tools including “creative changes to the physical environment, and daily, meaningful treatment activities” (p.28). No mention of art therapy as an effective prevention tool could be found in current literature on restrictive practices. However, art therapy has the capacity to meet many of the aforementioned goals and recommendations, as it is a creative, prevention-oriented intervention which supports self-expression and self-regulation, and therefore has the capacity to mitigate escalating levels of distress.

Art therapy in inpatient mental health services

The established benefits of art therapy in adult inpatient mental health services include developing greater self-awareness, social connection, self-expression, creativity, self-regulation, relaxation, and empowerment (Chiu et al., Citation2015; Dick, Citation2001; Laranjeira et al., Citation2019; Scope et al., Citation2017; Uttley et al. Citation2015). While the literature on art therapy in child and adolescent mental health highlighted similar benefits to those outlined in adult cohorts, it tends to focus on either specific therapeutic interventions or techniques in an inpatient setting (Lyshak-Stelzer et al., Citation2007; Nielsen, Citation2018; Nielsen et al., Citation2019; Wyder, Citation2019) or broad approaches to art therapy in child and adolescent mental health (Case & Dalley, Citation2007; Malchiodi, Citation2015; Riley, Citation2001; Rubin, Citation2005). A recent study examining a multidisciplinary group program run on an inpatient CAMHS unit found that young people deemed art therapy the most helpful modality when compared to several other diversional and therapeutic groups (Versitano et al., Citation2023). While noting the limited empirical evidence for the use of art therapy with children in mental health services, a recent systematic review of the effectiveness of art therapy for children diagnosed with mental health disorders found benefits for children who had experienced trauma (Braito et al., Citation2021).

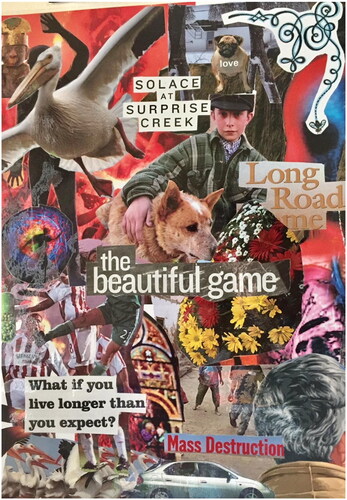

Young people admitted for care in acute inpatient settings have often trialled traditional psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions within the community and found these treatments to be ineffective in mitigating their mental health challenges (NSW Health, Citation2011; The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, Citation2020). Creative, person-centred interventions such as art therapy provide a safe, inviting alternative for young people to engage with during an admission. For some young people, artworks created during an admission may provide visual evidence of change or progress over time (). The permanence of the artwork produced in sessions is unique to art therapy when compared to verbal therapies and provides “tangible and undeniable testimony to their progress” (Hanes Citation2001, p.159).

Figure 1. Artwork created by young person during art therapy session prior to discharge. NB: Collage created using mixed media. A young person’s exploration of their hopes, fears, and ambivalence towards impending discharge after struggling with self-harm and suicidal ideation throughout their admission. “love…solace at surprise creek…Long Road Home…the beautiful game…Mass Destruction… What if you live longer than you expect?”

Art therapy is a creative, psychotherapeutic intervention which allows young people to explore and process overwhelming experiences by identifying feelings non-verbally. Further to this, art therapy shows promise in reducing rates of restrictive practices for young people in inpatient mental health settings (Lyshak-Stelzer et al., Citation2007, p. 167; Nielsen, Citation2018, p. 4). Concerningly, paediatric patients are far more likely to experience an incident of seclusion or restraint relative to adult patients (De Hert et al., Citation2011; NHS Benchmarking Network, Citation2019). Young people in acute inpatient services also have high rates of developmental trauma, and challenges with expressing their distress verbally, which can lead to an increased use of restrictive practices (Nielsen et al., Citation2019, p.165). In providing a safe, creative, non-verbal avenue of expression, levels of acute distress which often precipitate these incidents can be effectively de-escalated to achieve targeted prevention.

Our retrospective study examines the use of restrictive practices on an acute inpatient CAMHS unit in a metropolitan public hospital. The study aimed to identify whether there was an association between art therapy service provision, and a reduction in the use of restrictive practices. This naturalistic observational study utilised more than six years of data during which there were sustained periods of art therapy service provision which could be compared to periods without service.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval for this study was granted from the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/ETH12228). A waiver of consent was also granted as this data had already been routinely collected by the service, remained de-identified for the purpose of the study, and was retrospectively accessed providing sufficient protection of privacy to participants.

Data on restrictive practices which occurred between July 2015 and December 2021 on an 8-bed acute inpatient CAMHS unit of a metropolitan public hospital in Sydney, Australia were extracted from two discrete sources in order to optimise validity and reliability. Data included incidents which were documented in the Incident Information Management System (IIMS), and incidents documented in the seclusion and restraint registers stored on the unit. Data from these two sources were merged into a single data set to generate the most accurate documentation of all incidents which occurred. Duplicates were discarded using the incident ID as a reference point. Data on intramuscular injected (IM) sedation, also referred to as chemical restraint (NSW Health, Citation2020), oral PRN use (as-needed medications), and absconding were also included if they occurred in association with an incident of seclusion and/or physical restraint. Incidents were then analysed in a naturalistic ABAB design wherein phases of art therapy service provision were “B”, and phases without service provision were “A” ().

Table 1. Phases of service within naturalistic ABAB design.

The art therapy service included both group and individual arts-based therapeutic interventions, integrating directive and non-directive approaches to art therapy, delivered by a masters-qualified art therapist. Young people were invited to engage in a weekly art psychotherapy group, a studio art therapy group, and could also be referred for individual art therapy sessions by the treating team. The art psychotherapy group had a formal one-hour structure integrating a creative check in, artmaking time, a period of reflection on artworks and group process, and a brief check out (Riley, Citation2001; Rubin, Citation2011). Studio art therapy groups were less formal in nature, running for up to 3 hours with flexibility around young people engaging with creative projects for brief periods, or the full duration of the group (Moon & Lachman-Chapin, Citation2001). Young people were referred to individual art therapy for a variety of reasons. It may have been that visual or symbolic exploration was considered a gentler avenue of expression, e.g. when a young person has a known history of trauma, or perhaps a young person identified that art making was an existing therapeutic strategy and the treating team wished to explore therapeutic goals through a creative lens. A young person may also struggle to engage effectively with verbal psychotherapies, perhaps due to challenging experiences with past clinicians, situational mutism, or severe psychotic symptoms. Individual sessions focussed on a range of therapeutic goals and were structured to meet the unique needs of the young person referred.

Data on length of stay were extracted from hospital medical records, while readmission rates (i.e readmissions occurring within 28 days of discharge) were extracted from a New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health database for the period between January 2017 and December 2021. Readmission rates were not documented in this database prior to 2017. Data on length of stay and readmission rates were segmented into A and B phases, and a Mann–Whitney U Test was conducted to check for statistically significant differences between phases. Mean and standard deviation were also calculated for each phase. Using the data set generated by the merged IIMS reports and seclusion and restraint registers, the rate, frequency, duration, and total number of incidents of restrictive practices were calculated per month. Data was then segmented into the relevant A and B phases. All calculations were conducted using the same formulas as NSW Ministry of Health, replicating global standards for data reporting on restrictive practices (Bureau of Health Information, Citation2019; NSW Health, Citation2022). The calculation for rate was based on the number of events per 1,000 occupied bed days; for frequency, the percent of acute mental health admitted care episodes wherein an incident occurred; and for duration, the average length (in hours) of all incidents of seclusion and physical restraint occurring within a month.

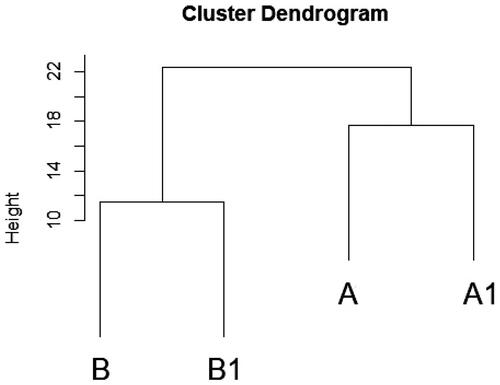

All variables in this study exhibited non-normal distributions, as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test with all p-values <.0001. Given the non-normality of the data, the Mann–Whitney U Test was used for statistical analyses. Due to the naturalistic study design, phase subcomponents differed in length (range 9–27 months). Such discrepancies in phase lengths could pose challenges for statistical analyses and interpretation. However, when both A phases (36 months) and B phases (38 months) were respectively combined this resulted in similar time periods. Euclidean distance was used as a measure of similarity between the A phases, and B phases as shown by the cluster dendrogram in . This analysis revealed that A and A1 phases were highly similar to each other, as were B and B1 phases, which provided justification for combining phases into more uniform intervals to enhance the statistical robustness of analyses and facilitate clearer interpretation of the results.

In addition to this, pairwise comparisons (Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjusted p-values) were also performed to demonstrate that, overall, there were no significant differences between the A and A1 phases, and no differences between the B and B1 phases across the variables that were shown to be significant in the AB design (supplementary material). However, there was a difference in the seclusion duration variable, which was significantly lower from the A to A1 phase, though it is not known what is driving this effect. A Mann-Whitney U test was then undertaken to compare A phases (without service), with B phases (with service) to determine whether there were statistically significant differences. A Benjamini-Hochberg multiple correction was applied to adjust the p-values and reduce the risk of a false positive. All inferential statistics were performed in Jasp (ver. 0.16.3.0).

Within the B phases (with service), incident dates were also examined to determine whether art therapy service delivery occurred on the same day as incidents of restrictive practices. Logistic regression was used to determine whether there were any statistically significant temporal associations with service delivery, as art therapy was offered on a part-time basis.

Diversional and therapeutic arts-based interventions were used sporadically on the unit prior to 2018. However, no permanent art therapy service was established by an experienced art therapist prior to the initial B phase of service. There were also variations to staffing, in addition to changes to the built environment throughout the study time-period. There was a 3-month gap in clinical data collection in 2016, and the unit was also closed for renovations in June 2019; both time periods were excluded from the analysis. There were also several waves of the covid-19 pandemic, however the service remained open throughout this time despite community lockdowns.

Results

Between July 2015 and December 2021 there were 1,352 total admitted episodes of care on the inpatient CAMHS unit (258 males, and 1,094 females). The mean age of young people admitted was 14.1 years (SD = 1.65), and the average length of stay was 14 days (SD = 24.74). The average length of stay during combined A phases (without service) was 16.54 days (SD = 28.20), however this was significantly lower during combined B phases (with service) with an average of 11.59 days (SD = 20.72) (U = 261872, p-value = .00002). Readmission rates for combined A phases (without service) averaged 24.28% (SD = 10.62) and were significantly lower in combined B phases (with service) with an average of 16.5% (SD = 11.66) (U = 526, p-value = .03).

Young people were admitted to the unit with a range of primary diagnoses (), predominantly mood (affective) disorders (25.59%), which comprised primarily of major depressive disorders (21.22%). Young people were also admitted due to suicidal ideation (13.68%), overdose (10.80%), and anxiety disorders (10.50%). Clinical and demographic characteristics

Table 2. Clinical and demographic characteristics.

The 1,352 episodes of care involved 948 individual young people who were admitted in this time-period. Of those 948 young people, 116 (12.23%) were involved in one or more incidents of seclusion and/or restraint. Further to this, 41 (35.34%) young people who experienced an incident of seclusion and/or restraint also had a known history of abuse and/or trauma. There were 404 episodes of care (29.88%) which represent readmissions wherein a young person had one or more previous episodes of care on the unit (range 2–4).

For the episodes of care in this time-period, all variables (rate, frequency, duration and total number of incidents) relating to physical restraint, seclusion, IM sedation, oral PRN use and absconding incidents were lower during combined B phases of art therapy service provision, when compared to combined A phases without service (). : Associations between art therapy service provision and restrictive practices for A phases (without service) and B phases (with service).

Table 3. Associations between art therapy service provision and restrictive practices for A phases (without service) and B phases (with service).

Results of the Mann–Whitney U test comparing combined A phases (without service) to combined B phases (with service) showed that the rate, frequency, duration, and total number of incidents of seclusion were significantly lower during B phases of art therapy service provision. The frequency and total number of incidents of physical restraint, and the rate, frequency, and total number of incidents of IM sedation were also significantly lower during combined B phases of art therapy service provision (U scores and p-values in ). Although all restrictive practices were lower in B phases, the duration and rate of physical restraint, and variables relating to use of oral PRN and absconding incidents did not reach statistical significance between A and B phases.

When examining specific incident dates within B phases (with service), only 2 incidents of seclusion occurred, neither of which took place on the same day as the art therapy service. Within these B phases, the odds of physical restraint were also 49% lower on days with art therapy service provision when compared to days without (OR = 0.51, 95% CI[0.27, 0.91], p-value = .028).

Discussion

The findings from this study indicate a clear association between the provision of art therapy, and a statistically significant reduction in the prevalence of restrictive practices such as seclusion, physical restraint, and IM sedation on an acute inpatient CAMHS unit. During phases without art therapy service, there are significantly higher rates of restrictive practices being used, indicating higher levels of acute distress for young people. Further to this, no incidents of seclusion, and a statistically significant reduced likelihood of physical restraint were found during specific days when the art therapy service was provided. This underscores the potential therapeutic impact of art therapy in this study context. The odds ratio suggests that, on average, the likelihood of physical restraint occurring was approximately half as likely on days when art therapy services were offered, compared to days without. This result indicates a specific, positive association with the provision of art therapy. There was also a significantly lower average length of stay, and average readmission rates during phases of art therapy service provision. Higher readmission rates and length of stay reflect increased time periods wherein a young person remains in a locked hospital environment, while also increasing financial costs to the health service (Feng at al., Citation2017). While shorter length of stay has been associated with increased readmission rates (Figueroa et al., Citation2004), our analysis demonstrated that both these measures were lower during phases of art therapy service provision. From this, it can be inferred that the availability of art therapy during an inpatient admission may lessen the need for an extended length of stay, and that these effects can extend into the community, therefore lowering the likelihood of readmission. Prospective qualitative research could help to identify these putative mechanisms, which could then be disambiguated by a randomised control trial. The current study alone cannot confirm causality between art therapy and reduced use of restrictive practices. However, the associative findings are striking, and have significant implications for clinical service planning, therefore it is worth considering the mechanisms of art therapy relative to these findings. The art therapy service in our study was a fixed component of the therapeutic group program, scheduled on days with historically increased levels of agitation and boredom for young people. Boredom, which can be a result of occupational deprivation commonly occurring in restrictive environments such as a locked unit (Whiteford et al., Citation2020), often precipitates increased agitation or aggression, and is found to be a contributing factor in the potential increase of restrictive practices (Larue et al., Citation2009, NSW Health, Citation2017). The presence of a multidisciplinary team who can provide trauma-informed, recovery-oriented care, and a predictable therapeutic program has been recommended to address this risk (NSW Health, Citation2017, p. 41). Providing creative therapeutic services such as art therapy which can effectively engage young people, support emotional regulation, and encourage positive social interaction may therefore contribute to the prevention of increased aggression or agitation which typically occur prior to an incident of seclusion and/or restraint.

More than one third of young people who had experienced an incident of seclusion or restraint in our study had a known history of abuse and/or trauma. Trauma-informed care emphasises the need for psychological, emotional, and physical safety to provide opportunities for a sense of control and empowerment (Hopper et al., Citation2010), both of which are removed when restrictive practices are enacted. Trauma-informed art therapy practices acknowledge that verbal processing can often be challenging to access at times of increased distress, and that artmaking can be an emotionally regulating experience and effective de-escalation strategy when conducted within a safe, therapeutic relationship with a qualified art therapist (Chong, Citation2015; Nielsen, Citation2018). In a study examining the efficacy of trauma-focused art therapy in reducing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in an inpatient psychiatric facility for youth (Lyshak-Stelzer et al. Citation2007), findings showed that there was substantially more PTSD symptom reduction for the trauma-focused art therapy group compared with the control group (arts & crafts). Further to this, there was a reduced likelihood of seclusion for young people in the trauma-focused art therapy condition (p.167). These findings, in addition to our study, provide evidence to support the value of art therapy interventions in contributing to the reduction of restrictive practices with children and adolescents in inpatient mental health care.

There are several limitations to our study. The potential impact of staffing changes, and changes to the built environment warrant further investigation to understand the relative effect size of these incidents. This could be addressed in future research utilising a randomised control trial which could isolate various contributing factors. We used a naturalistic ABAB service delivery pattern for data collection. However, there were no differences in the respective A and B phases, highlighting the ability to combine them into single A and B phases for the purposes of inferential statistics. It is relevant to note that one variable, seclusion duration, was significantly lower from A to A1 phase. Given that all other variables were not significantly different, we are unsure what is driving this effect which may warrant a follow-up study to investigate this further.

During the average admission of 14 days, a person may engage in group and/or individual art therapy sessions on just a few occasions. Therefore, it can be challenging to isolate the impact of art therapy within the context of a multimodal treatment program. Nonetheless, multiple diversional creative groups which might alleviate occupational deprivation and boredom were provided to young people across all A and B phases (including music, art, and craft activities), yet this did not prevent the increase in restrictive practices associated with the suspension of the art therapy service. Art therapy interventions are often conflated with diversional creative activities (Van Lith & Fenner, Citation2011; Van Lith & Spooner, Citation2018). However, the skills, qualifications, program design, and delivery significantly differ. While diversional arts activities tend to focus on skill development and enjoyment (Van Lith & Spooner, Citation2018), art therapy frameworks provide opportunities for emotional regulation, safety, self-expression, and the exploration of therapeutic goals (Gabel & Robb, Citation2017; Van Lith & Spooner, Citation2018). Young people also experience these modalities differently, as highlighted in a recent survey conducted with young people where art therapy was perceived as the most helpful group therapy intervention running on an inpatient CAMHS unit when compared with several other diversional arts activities, and verbal psychotherapy groups (Versitano et al., Citation2023).

It is also important to acknowledge the complexity of the therapeutic environment on an acute inpatient unit, and the varying factors, e.g. staffing changes, built environment variations, and the COVID-19 pandemic, which can influence an increase or decrease in restrictive practices. However, despite a significant increase in the number of self-harm or suicidal ideation presentations in children and adolescents to emergency departments across NSW, Australia since 2015 (Sara et al., Citation2022), restrictive practices on the unit in this study were still significantly lower after the introduction of the art therapy service.

Conclusion

While the eventual elimination of restrictive practices in inpatient mental health services is a multi-faceted and ongoing endeavour, art therapy can effectively and significantly contribute to the reduction of these harmful practices alongside other systemic and therapeutic interventions. Our study has established that there was a statistically significant reduction in incidents of seclusion, physical restraint, and IM sedation during the phases wherein the art therapy service was present on the inpatient CAMHS unit. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in length of stay and readmission rates when art therapy was provided. These compelling findings are relevant for mental health services internationally, especially given the scarcity of literature on art therapy in child and adolescent mental health care (Braito et al., Citation2021; Cornish, Citation2013).

Our findings provide evidence for the importance of establishing creative therapeutic interventions in inpatient mental health settings. Specifically, the provision of permanent art therapy services run by qualified art therapists in being able to support the prevention and reduction of harmful restrictive practices for young people. Reducing restrictive practices in these settings is certainly a complex undertaking. However, art therapy has an important role in providing effective, trauma-informed support to young people in inpatient care.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the young people whose experiences were able to provide greater insights into how to effectively reduce these harmful practices; the Health Education and Training Institute (HETI) who provided funding to undertake this research as part of the Mental Health Research Award; the nursing, allied health and medical staff on the inpatient CAMHS unit who work tirelessly to create a safe, therapeutic environment for young people; Kim Gregorio and Dr Sheridan Linnell who provided their expert guidance and support.

Disclosure statement

The first author acknowledges her dual role as both clinician and researcher. No further conflicts of interest have arisen.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrassy, B. M. (2016). Feelings thermometer: An early intervention scale for seclusion/restraint reduction among children and adolescents in residential psychiatric care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12151

- Azeem, M. W., Aujla, A., Rammerth, M., Binsfeld, G., & Jones, R. B. (2018). Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints at a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 24(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00262.x

- Bigwood, S., & Crowe, M. (2008). ‘It’s part of the job, but it spoils the job’: A phenomenological study of physical restraint. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(3), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00526.x

- Braito, I., Rudd, T., Buyuktaskin, D., Ahmed, M., Glancy, C., & Mulligan, A. (2021). Review: systematic review of effectiveness of art psychotherapy in children with mental health disorders. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 191(3), 1369–1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02688-y

- Bureau of Health Information. (2019). Measurement Matters: Reporting on Seclusion and Restraint in NSW Public Hospitals. Bureau of Health Information. https://www.bhi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/507669/BHI_MM_Seclusion_and_restraint.pdf

- Caldwell, B., Albert, C., Azeem, M. W., Beck, S., Cocoros, D., Cocoros, T., Montes, R., & Reddy, B. (2014). Successful seclusion and restraint prevention efforts in child and adolescent programs. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(11), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20140922-01

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2007). Working with children in art therapy. Routledge.

- Chiu, G., Hancock, J., & Waddell, A. (2015). Expressive arts therapy group helps improve mood state in an acute care psychiatric setting (Une thérapie de groupe ouverte en studio basée sur les arts de la scène améliore l’humeur des patients en psychiatrie dans un établissement de soins intensifs). Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 28(1–2), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2015.1100577

- Chong, C. Y. J. (2015). Why art psychotherapy? Through the lens of interpersonal neurobiology: The distinctive role of art psychotherapy intervention for clients with early relational trauma. International Journal of Art Therapy, 20(3), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2015.1079727

- Cornish, S. (2013). Is there a need to define the role of art therapy in specialist CAMHS in England? Waving not drowning. A systematic literature review. Art Therapy Online, 4(1).

- De Hert, M., Dirix, N., Demunter, H., & Correll, C. U. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of seclusion and restraint use in children and adolescents: a systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(5), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-011-0160-x

- Dean, A. J., Gibbon, P., McDermott, B. M., Davidson, T., & Scott, J. (2010). Exposure to aggression and the impact on staff in a child and adolescent inpatient unit. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2009.01.002

- Delaney, K. R. (2001). Developing a restraint-reduction program for child/adolescent inpatient treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 14(3), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2001.tb00304.x

- Dick, T. (2001). Brief group art therapy for acute psychiatric inpatients. American Journal of Art Therapy, 39(4), 108.

- Duke, S. G., Scott, J., & Dean, A. J. (2014). Use of restrictive interventions in a child and adolescent inpatient unit–predictors of use and effect on patient outcomes. Australasian Psychiatry, 22(4), 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856214532298

- Felver, J. C., Jones, R., Killam, M. A., Kryger, C., Race, K., & McIntyre, L. L. (2017). Contemplative intervention reduces physical interventions for children in residential psychiatric treatment. Prevention Science, 18(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0720-x

- Feng, J. Y., Toomey, S. L., Zaslavsky, A. M., Nakamura, M. M., & Schuster, M. A. (2017). Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics, 140(6), e20171571. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1571

- Figueroa, R., Harman, J., & Engberg, J. (2004). Use of claims data to examine the impact of length of inpatient psychiatric stay on readmission rate. Psychiatric Services, 55(5), 560–565. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.560

- Gabel, A., & Robb, M. (2017). (Re) considering psychological constructs: A thematic synthesis defining five therapeutic factors in group art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.05.005

- Gaskin, C. J., Elsom, S. J., & Happell, B. (2007). Interventions for reducing the use of seclusion in psychiatric facilities: review of the literature. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(4), 298–303. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034538

- Hanes, M. J. (2001). Retrospective review in art therapy: Creating a visual record of the therapeutic process. American Journal of Art Therapy, 40(2), 149. http://ezproxy.uws.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/retrospective-review-art-therapy-creating-visual/docview/199244397/se-2

- Hopper, E. K., Bassuk, E. L., & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874924001003010080

- Huckshorn, K. A. (2004). Reducing seclusion & restraint use in mental health settings: Core strategies for prevention. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 42(9), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20040901-05

- Huckshorn, K. A., & LeBel, J. L. (2013). Trauma informed care. In K. Yeager, D. Cutler, D. Svendsen, & G.M. Sills (Eds.), Modern community mental health work: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 62–83). Oxford University Press.

- Huckshorn, K. A., Cap, I., & Director, N. T. A. C. (2005). Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Consolidated%20Six%20Core%20Strategies%20Document.pdf

- Knox, D. K., & Holloman, G. H. (2012). Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the American association for emergency psychiatry project Beta seclusion and restraint workgroup. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867

- Laranjeira, C., Campos, C., Bessa, A., Neves, G., & Marques, M. I. (2019). Mental health recovery through art therapy: A pilot study in Portuguese acute inpatient setting. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(5), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1563255

- Larue, C., Dumais, A., Ahern, E., Bernheim, E., & Mailhot, M. P. (2009). Factors influencing decisions on seclusion and restraint. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(5), 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01396.x

- LeBel, J., & Goldstein, R. (2005). The economic cost of using restraint and the value added by restraint reduction or elimination. Psychiatric Services, 56(9), 1109–1114. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1109

- LeBel, J., Huckshorn, K. A., & Caldwell, B. (2010). Restraint use in residential programs: Why are best practices ignored? Child Welfare, 89(2), 169–187.

- LeBel, J., Stromberg, N., Duckworth, K., Kerzner, J., Goldstein, R., Weeks, M., Harper, G., LaFlair, L., & Sudders, M. (2004). Child and adolescent inpatient restraint reduction: A state initiative to promote strength-based care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200401000-00013

- Lyshak-Stelzer, F., Singer, P., Patricia, S. J., & Chemtob, C. M. (2007). Art therapy for adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Art Therapy, 24(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129474

- Malchiodi, C. (Ed.). (2015). Creative interventions with traumatized children (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Mohr, W. K., Martin, A., Olson, J. N., Pumariega, A. J., & Branca, N. (2009). Beyond point and level systems: Moving toward child-centered programming. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015375

- Moon, C. H., & Lachman-Chapin, M. (2001). Studio art therapy: Cultivating the artist identity in the art therapist. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Muir-Cochrane, E., O’Kane, D., & Oster, C. (2018). Fear and blame in mental health nurses’ accounts of restrictive practices: Implications for the elimination of seclusion and restraint. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1511–1521. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12451

- Muir-Cochrane, E., Oster, C., & Gerace, A. (2014). The use of restrictive measures in an acute inpatient child and adolescent mental health service. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(6), 389–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.015

- NHS Benchmarking Network. (2019). International mental health comparisons 2019: Child and adolescent, adult, older adult services. NHS Benchmarking Network.

- Nielsen, F. (2018). Responsive art psychotherapy as a component of intervention for severe adolescent mental illness: A case study. Art Therapy OnLine, 9(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.atol.v9i1.487

- Nielsen, F., Isobel, S., & Starling, J. (2019). Evaluating the use of responsive art therapy in an inpatient child and adolescent mental health services unit. Australasian Psychiatry, 27(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856218822745

- NSW Health. (2011). Children and adolescents with mental health problems requiring inpatient care. NSW Health. https://www.mentalhealthcarersnsw.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/PD2011_016-Children-and-Adolescents-with-Mental-Health-Problems-Requiring-Inpatient-Care.pdf

- NSW Health. (2017). The review of seclusion, restraint and observation of consumers with a mental illness in NSW health facilities. NSW Health. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/reviews/seclusionprevention/Documents/report-seclusion-restraint-observation.pdf

- NSW Health. (2020). Seclusion and restraint in NSW health settings. NSW Health. https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2020_004.pdf

- NSW Health. (2022). 2022–23 KPI and Improvement Measure. Data Supplement. Part 1 of 2 (Key Performance Indicators). NSW Health. https://www.hnehealth.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/426561/3a-2021-22_SA-KPI_Data_Supplement_V1-03-20220331.pdf

- Nunno, M. A., Holden, M. J., & Tollar, A. (2006). Learning from tragedy: A survey of child and adolescent restraint fatalities. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(12), 1333–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.02.015

- Riley, S. (2001). Art therapy with adolescents. The Western Journal of Medicine, 175(1), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1136/ewjm.175.1.54

- Riley, S. (2001). Group process made visible: Group art therapy. Brunner-Routledge.

- Rubin, J. A. (2005). Child art therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Rubin, J. A. (2011). The art of art therapy: What every art therapist needs to know. Routledge.

- Sara, G., Wu, J., Uesi, J., Jong, N., Perkes, I., Knight, K., O’Leary, F., Trudgett, C., & Bowden, M. (2022). Growth in emergency department self-harm or suicidal ideation presentations in young people: Comparing trends before and since the COVID-19 first wave in New South Wales, Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674221082518

- Scope, A., Uttley, L., & Sutton, A. (2017). A qualitative systematic review of service user and service provider perspectives on the acceptability, relative benefits, and potential harms of art therapy for people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 90(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12093

- The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network. (2020). Admission to acute mental health unit: Procedure. https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/_policies/pdf/2017-179.pdf

- Uttley, L., Scope, A., Stevenson, M., Rawdin, A., Taylor Buck, E., Sutton, A., Stevens, J., Kaltenthaler, E., Dent-Brown, K., & Wood, C. (2015). Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Health Technology Assessment, 19(18), 1–120. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19180

- Valenkamp, M., Delaney, K., & Verheij, F. (2014). Reducing seclusion and restraint during child and adolescent inpatient treatment: Still an underdeveloped area of research. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 27(4), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12084

- Van Lith, T., & Fenner, P. (2011). The practice continuum: Conceptualising a person-centred approach to art therapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Arts Therapy, 6(1), 17–21.

- Van Lith, T., & Spooner, H. (2018). Art therapy and arts in health: Identifying shared values but different goals using a framework analysis. Art Therapy, 35(2), 88–93.https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2018.1483161

- Versitano, S., Butler, G., & Perkes, I. (2023). Art and other group therapies with adolescents in inpatient mental health care. International Journal of Art Therapy, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2023.2217891

- Whiteford, G., Jones, K., Weekes, G., Ndlovu, N., Long, C., Perkes, D., & Brindle, S. (2020). Combatting occupational deprivation and advancing occupational justice in institutional settings: Using a practice-based enquiry approach for service transformation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802261986522

- Wieman, D. A., Camacho-Gonsalves, T., Huckshorn, K. A., & Leff, S. (2014). Multisite study of an evidence-based practice to reduce seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Psychiatric Services, 65(3), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300210

- World Health Organization. (2019). Strategies to end the use of seclusion, restraint and other coercive practices – WHO Quality Rights training to act, unite and empower for mental health. World Health Organization.

- Wyder, S. (2019). The house as symbolic representation of the self: Drawings and paintings from an art therapy fieldwork study of a closed inpatient adolescents’ focus group. Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance et de l’Adolescence, 67(5-6), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurenf.2019.05.003