Abstract

Background

Personal recovery is operationalized in the CHIME framework (connectedness, hope, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment) of recovery processes. CHIME was initially developed through analysis of experiences of people mainly with psychosis, but it might also be valid for investigating recovery in mood-related, autism and other diagnoses.

Aims

To examine whether personal recovery is transdiagnostic by studying narrative experiences in several diagnostic groups.

Methods

Thirty recovery narratives, retrieved from “Psychiatry Story Bank” (PSB) in the Netherlands, were analyzed by three coders using CHIME as a deductive framework. New codes were assigned using an inductive approach and member checks were performed after consensus was reached.

Results

All five CHIME dimensions were richly reported in the narratives, independent of diagnosis. Seven new domains were identified, such as “acknowledgement by diagnosis” and “gaining self-insight”. These new domains were evaluated to fit well as subdomains within the original CHIME framework. On average, 54.2% of all narrative content was classified as experienced difficulties.

Conclusions

Recovery stories from different diagnostic perspectives fit well into the CHIME framework, implying that personal recovery is a transdiagnostic concept. Difficulties should not be ignored in the context of personal recovery based on its substantial presence in the recovery narratives.

Classification:

Background

According to service users, supportive social relationships, personal wellbeing, mental health treatment that looks at “the person behind the symptoms”, and finding meaningful life activities are important elements of personal recovery (Jose et al., Citation2015; Leamy et al., Citation2011). (Re)building personal relationships and experiencing a sense of belonging are deemed the most important factors in stimulating overall recovery (i.e. clinical, societal, and personal recovery) (De Ruysscher et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, integration of personal recovery support into routine clinical practice remains a challenge.

A recovery-oriented approach focuses on strengths and abilities rather than symptoms or deficits, which encourages individuals to achieve their personal goals and may help reduce self-stigma (Anthony, Citation1993; Slade, Citation2009). Its focus on empowerment encourages individuals to take back control over their life and to achieve (more) autonomy over their life, treatment goals, and decisions (Davidson & Strauss, Citation1992; Deegan, Citation1988). During the last 10 years, the concept of personal recovery has been defined in more detail by systematic reviews and narrative syntheses on overall recovery experiences (Dell et al., Citation2021; Jose et al., Citation2015). These studies describe personal recovery as a personal transformation process from a negative sense to a positive sense of self, with significant roles for family and society. They found multiple dualisms in the way overall recovery is being approached, such as clinical-personal, individualistic-social, and process-outcome. Overall recovery can also be oriented in various ways, such as self-orientation, family-orientation, social-orientation and illness-orientation. A conceptual framework that encompasses these aspects is therefore highly needed.

Until now, a widely used comprehensive conceptual framework for personal recovery is the CHIME framework (Leamy et al., Citation2011) which was developed through a systematic review and narrative synthesis of personal recovery narratives in 97 studies. CHIME consists of five dimensions: connectedness (e.g. support from others, being part of the community), hope and optimism (e.g. motivation to change, positive thinking, and valuing success), identity (e.g. rebuilding/redefining positive sense of self, overcoming stigma), meaning in life (e.g. meaning of mental illness experiences, quality of life) and empowerment (e.g. personal responsibility, control over life). Subsequent systematic reviews have suggested this framework should be extended with a sixth dimension: “Difficulties” (Stuart et al., Citation2017; Van Weeghel et al., Citation2019). It was argued that difficulties can be(come) part of somebody’s life, and that acceptance and learning to deal with experienced difficulties and traumas is part of personal recovery. However, the difficulties are hardly studied with empirical data and there is no consensus about extending the CHIME framework with difficulties, which is focused around personal recovery processes.

Although CHIME is widely used, most of the studies that were used to develop the framework focused on people with psychotic disorders. Only three of the studies focused specifically on overall recovery from depression and four studies on addiction or substance abuse (Leamy et al., Citation2011). Six studies included severe mental illness participants of which at least 50% had a psychosis-related diagnosis. Consequently, there was an overrepresentation of people with psychosis, compared to other mental health problems, in the development of the CHIME framework. It is therefore uncertain whether the CHIME framework of personal recovery can be used transdiagnostically (Hare-Duke et al., Citation2023).

Several studies have recently discussed whether the CHIME framework could be applied to other mental health diagnoses, such as depression (Richardson & Barkham, Citation2020), eating disorders (Wetzler et al., Citation2020), bipolar disorders (Jagfeld et al., Citation2021) and substance use disorders (Dekkers et al., Citation2020). The first results are promising and suggest that personal recovery is a relevant concept across different diagnoses, although some additions to and reorganization of the CHIME dimensions were suggested. However, for some diagnoses groups it is still unclear whether it is suitable to use a personal recovery-oriented focus, in particular for anxiety and autism.

The concept of personal recovery, as operationalized by the CHIME framework, has not been studied yet in relation to autism. Autism is considered a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and therefore full clinical recovery may not be possible, but personal recovery (i.e., “living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even alongside the limitations of illness” (Anthony, Citation1993)) can apply very well to lifelong issues such as autism and bipolar disorder. Autism is also seen as a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference which can express itself in certain forms of genius (Kapp et al., Citation2013; Silberman, Citation2015). Moreover, personal recovery-related themes, such as acceptance, coping with difficulties, understanding identity, meaning-making of mental health problems, and rebuilding a positive sense of the self, seem to be important in experiences with autism (Lewis, Citation2016; Müller et al., Citation2008). Connectedness could also align with autism, but may be presented in different wording, such as “feelings of otherness” and a wish for a “sense of belonging” (Lewis, Citation2016; Müller et al., Citation2008).

To summarize, although CHIME was developed using predominantly experiences of people with psychotic disorders, there are indications that CHIME could be used as a transdiagnostic framework for personal recovery. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine whether personal recovery is a transdiagnostic concept by testing the fit of the existing CHIME framework with various diagnoses on the spectrum of severe mental illness. We will analyze recovery narratives of people with lived experience of severe mental health problems with a diagnosis of autism, mood-related, multiple diagnoses (various co-morbid diagnoses) or psychosis. We will investigate 1) whether all five CHIME-dimensions appear in the narratives of people with different diagnoses and 2) whether any additional sub-categories will be identified that may fit within or outside the CHIME framework.

Methods

Study design

In this mixed methods study, we performed qualitative analysis of text-based recovery narratives using an a priori codebook with a combined deductive and inductive approach. This was followed by a quantification of our results to provide a more comprehensive insight in the strength of the presence of codes in the narratives, to benefit the interpretation of our findings and allow for an answer to our research questions (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2007). We followed a coding reliability approach to reduce researcher subjectivity, using multiple steps to effectively use a qualitative codebook in applied thematic analysis (Guest et al., Citation2012). We had the preconception that the CHIME framework might be universally applicable across diverse populations and contexts, with acknowledgement that some dimensions (e.g. connectedness) would be somewhat more or less fitting for autism. To avoid overlooking or downplaying aspects of personal recovery outside of CHIME, we added the option “New Codes” (please see codebook paragraph). Being aware of our preconception, we tried to remain open to unexpected themes and variations to minimize its influence on the inductive process. However, our goal was merely to test the fit of the CHIME framework for different diagnostic groups, and to detect potential new categories, in case where the framework did not fit. We have aimed to promote transferability (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) of our results by explaining our methods in a clear and informative way.

Recovery narratives

We used recovery narratives of the Psychiatry Story Bank (PSB) which is an initiative of the Psychiatry Department of University Medical Centre Utrecht in the Netherlands. The PSB contains a collection of mental health-oriented narrative experiences from service users (Van Sambeek et al., Citation2021), caregivers, and professionals. Recovery narratives were included if they met the eligibility criteria of a recovery narrative according to the INCRESE instrument (Llewellyn-Beardsley et al., Citation2020).

To collect narratives, participants were interviewed using narrative and semi- structured interview techniques. Flexible use of a topic guide (see supplemental data of Van Sambeek et al. (Citation2021)) and minimal interruption of conversational flow aided to collection of additional information on personal recovery. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and summarized by editors into 1–2 page written narratives. Participants were asked to confirm whether the summarized narrative was an authentic reflection of their experience(s) before being published on the website of PSB (public domain). Narratives were published only when the participants agreed with the final version (and all their suggestions were processed).

Informed consent was provided for the use of narratives for scientific research purposes. The project was evaluated by The Medical Ethical Review Committee (MERC) of the University Medical Center of Utrecht, who confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act did not apply (Reference number: 16 626/C). Subsequently, official approval of this study by the MERC was not required.

Narrative selection

The narratives included in this study are personal accounts of patients with lived experience in mental health. A total of 30 out of 40 available narratives were selected and based on self-reported diagnoses divided in an autism (n = 6), mood related (n = 10), multiple diagnoses (n = 6), or psychosis-related group (n = 8). Ten of the 20 mood-related narratives were excluded at random to avoid an overrepresentation of mood-related recovery narratives in this study.

Convergent representation check

A representation check was performed on content and theme-level of the narratives in relation to the full interview transcripts. Five of the transcripts and the five corresponding summarized narratives were compared on important content and present (CHIME) themes by the main researcher (ML) and checked by two other reviewers (JB, SCa). We found that all relevant topics in the extended interviews were also included in the summarized narratives. Therefore, we opted to only analyze the summarized narratives in this study.

Codebook for personal recovery

The CHIME framework consists of five domains of personal recovery processes, comprising a total of 21 subcategories and 41 sub-subcategories (Leamy et al., Citation2011). We used the framework hierarchy of CHIME as our codebook. For example “friends and peer support” was a subcode of “

“support from others”, which was one of the subcodes of the ‘Connectedness’ dimension. We opted to expand the CHIME codebook with a sixth domain, namely difficulties, based on the recommendation of Stuart et al. (Citation2017) and Van Weeghel et al. (Citation2019). Any traumatic experiences and illness-related hardships in the narratives are coded as “Difficulties”. We will refer to it as CHIME-D where the “D” stands for difficulties. All information not related to personal recovery (i.e. CHIME or “New Code”) or “Difficulties” were coded as “Not Relevant” (e.g. the place where someone was born). See Appendix 1 for the full codebook used in this study.

Data analysis

We used the software ATLAS.ti 22 for the qualitative coding of the narratives. Titles and general introductions of the narratives were excluded from coding to prevent bias (due to duplicates in codes), as the introductions of the narratives summarized content presented in the narrative. One researcher was assigned with the role of lead codebook manager (ML), and took charge of all changes in the process and agreements that were made on how to use the codebook. There were four coders (JB, SCr, MB, and ML), and to promote dependability and credibility (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985), we performed investigator triangulation (Denzin, Citation1978) by coding narratives with three coders per narrative. Coding of each narrative was performed sentence-by-sentence (one sentence = one quotation), with a restriction of maximally three codes per quotation. For the coding only one sub-subcategory from the same subcategory was allowed, and in case of multiple equally suitable sub-subcategories (e.g. 1.1.3 and 1.1.4), the overarching subcategory was coded (i.e. 1.1.) or even the general CHIME category (i.e. 1). This prevented a situation where more than three codes per quotation were needed. For the deductive part of our analysis (Step 1), we used the Applied Thematic Analysis approach (Guest et al., Citation2012). Each coder individually examined whether the a priori codebook had a suitable code for every sentence in a narrative. If not, no code was assigned for these quotations. Second, an inductive approach (Step 2) was used for the unassigned sentences, where the coders individually assigned new codes to these quotations. We followed the steps of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) and the newly found codes were reviewed in relation to the pre-existing CHIME dimensions. Third, the three coders of each narrative reached a consensus (Step 3) on all of the assigned codes (i.e. by discussing quotations with disagreement in the assigned codes until agreement was met on when and when not to use a particular code). Subsequently, all narratives were analyzed a second time by two coders per narrative, this time using the updated codebook including the new codes, followed by a last consensus meeting (i.e. arguments for different or new codes were presented by the coders and discussed until agreement was met about the best fitting code(s)). To finalize the data synthesis, a member check (lived experience experts) and peer debrief (independent researchers) were performed to evaluate the newly assigned codes and considered their fit within or outside of the CHIME framework.

Descriptive statistics

The total number of assigned codes in all narratives was counted, as well as all codes within a code group (i.e. one of the CHIME dimensions, Difficulties, New Code, or Not Relevant). We also counted the amount of narratives that contained one or more codes within these code groups, relative to all narratives and per diagnoses group. Last, the average coding percentage within a code group that was assigned to narratives, and the maximum coding percentages were calculated.

Results

Overall findings

The 30 narratives had a mean length of 857 words (SD = 106; range = 660–1093) and contained a total of 1.850 quotations (range = 36–102) to which one or more codes were assigned (in total: 2.083). The age range of the narrators was 22–71 years old. Narrators were Dutch residents, with 18 females and 12 males.

Deductive analysis CHIME-D codebook

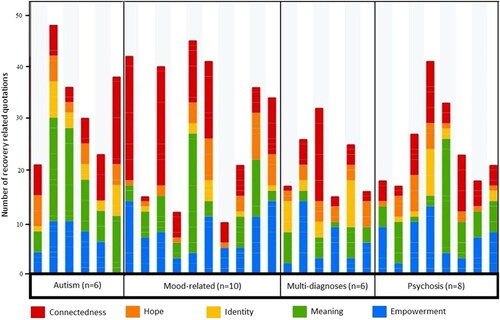

The codes of the CHIME framework made up 33.8% of all the assigned codes (Connectedness = 213; Hope and optimism = 99; Identity = 58; Meaning = 127; Empowerment = 207) in the 30 recovery narratives. Connectedness and empowerment codes had the greatest presence in the narratives (∼10% of the content), compared to the other CHIME elements (∼3–6%). The difficulties code was assigned 1.132 times (54.3% of codes) and the “Not Relevant” code was used 130 times (6.2% of codes). The deductive analysis results per dimension are presented in (step 1).

Table 1. Deductive analysis of CHIME-D presence and additional dimensions in all narratives.

New codes

We identified seven new codes using an inductive approach (Step 2) which were assigned to 117 quotations (5.6% of codes). The new codes were rated positively (as adequate descriptions for their corresponding quotations) during both the member check (n = 4) and peer debrief (n = 2). All new codes were deemed subdomains that can be positioned within one or more of the CHIME dimensions and were positioned according to their best-rated fit (see ). The ordering criterium (shown below) is according to the number of narratives containing the new code.

Table 2. New codes (shown in bold) and categorization within the CHIME framework.

The first new code was ‘gaining self-insight’. Narrators described that what they learned about themselves gave insight into who they are and their lived experience of mental health problems. It shed new light on what happened and gave meaning to their mental illness experiences.

“I have become more empathetic and know what I had to go through.” [Narrative mood-related - 3]

The second new code was “acknowledgement through diagnosis”. Narrators described that receiving a diagnosis was a relief. It led to better understanding and acknowledgement of the issues the narrators were dealing with.

“It was confronting to hear that I have Asperger’s, but it also felt like a liberation. Now I understand why I am different and that it has a deeper cause than just my own choices and my behavior.” [Narrative autism - 4]

The third new code was “recognizing yourself in others & feeling connected to others”. Narrators mentioned that they recognized themselves in family members (e.g. with similar lived experience of mental health problems) or other people (e.g. through watching a documentary or reading a book). This led to insight and development of the narrator’s identity.

“I recognize a lot of my mother in myself. Her restlessness is also inside of me.” [Narrative autism - 3]

The fourth new code “being seen as human”. Narrators explained in their narratives that factors such as receiving personal attention and being able to ask questions, care professionals disclosing their own experiences, and a pleasant environment with a manned desk all contributed to being seen as equal humans.

“During this therapy I experienced for the first time that therapists are also just people. Less hierarchy, more personal attention. [.] This makes the relationship feel much more equal and you get the feeling that they see you as a human being rather than as a patient.” [Narrative mood-related 4]

The fifth new code was “distancing yourself from or shutting down unhealthy relationships”. Narrators described situations in which they actively chose to (temporarily) reduce or end contact with people who had a negative impact on their lives (e.g. by reminding them of physical or emotional abuse, a cheating (ex)-partner, or the person who triggered their addiction). Distancing themselves from these relationships helped the narrators to (re)gain control over life.

“I also said goodbye to a number of people who were not good for me.” [Narrative psychosis -1]

The sixth code was “letting go of resentments, anger, or other negative emotions”. One narrator spoke of letting go of resentment and anger toward his father after his passing a few years ago and that the last memory of his father was their good final conversation.

“The anger towards my father has now subsided.” [Narrative multiple diagnoses – 3]

Another narrator was able to forgive the mental health care institution for what went wrong in their recovery process, by accepting that humans simply make mistakes. It helped these narrators to rebuild and give positive meaning to their lives.

The last code was “support from an animal, pet or assistance dog”. One narrator described that she always suffered from prejudices by people, but not by her dog.

“I have suffered from these prejudices all my life and that is why I get along so well with dogs.” [Narrative autism – 6]

She described to feel stress throughout the day without being companioned by her dog, and to feel more relaxed when her dog is around. The dog also helped this narrator to estimate what people in different social situations are feeling and understand whether the atmosphere is relaxed or tense. The narrator described an experience of feeling connected and supported by a dog.

Including the newly categorized codes, the overall results show that more than half of the narratives (17/30) contain all five CHIME dimensions. Twelve narratives contained four CHIME dimensions and the remaining narrative contained three CHIME dimensions. This is visualized in .

Transdiagnostic analysis

The five CHIME dimensions were widely reported across the narratives, independent of diagnosis. “Connectedness” and “Empowerment” were assigned most often across the narratives, with “Connectedness” being present in 100% of the narratives, although “Meaning in life” was the most frequently assigned code in the autism narratives. “Identity” was reported the least, although “Identity” codes were present in 100% of the autism narratives. Multiple diagnoses narratives had fewer CHIME codes compared to the other diagnostic groups, because the majority of the narratives focused on experienced “Difficulties” (M = 54.2%) and overcoming them.

The new code “Acknowledgement through diagnosis” was most frequently used in autism narratives (5/6), once in a narrative about multiple diagnoses (1/6) and once in a mood-related narrative (1/10), but not in narratives about psychotic experiences. In , the new codes are integrated into the five CHIME dimensions per diagnostic group.

Table 3. New codes integrated within CHIME dimensions per diagnosis (including categories difficulties and not relevant).

Discussion

This study examined whether personal recovery, operationalized by using the CHIME framework, is a transdiagnostic concept that can be generalized to people with mood, autism and multiple mental health disorders. The CHIME dimensions were present in the recovery narratives, regardless of diagnosis, which suggests that personal recovery is indeed a transdiagnostic concept. Especially, “Connectedness” was present in all narratives and together with ‘Empowerment’ most strongly represented across all narratives and diagnoses. An exception was narratives about autism, in which “Meaning in life” had the strongest presence. Moreover, this study identified seven potential additions to the CHIME framework, which could enhance the transdiagnostic applicability of the concept of personal recovery. Although this study specifically investigated recovery narratives, the majority of the narrative content still featured the experienced ‘Difficulties’ and traumas of the narrators.

Interpretation of findings

Personal recovery as operationalized by the CHIME dimensions was richly reported across all narratives regardless of diagnosis, thus indicating that it can be seen as a transdiagnostic concept. However, there appears to be differences in emphasis between different diagnostic groups. For example, “Acknowledgement through diagnosis” was found an important topic in almost all autism narratives, but it was only mentioned in one mood-related and one multi-diagnoses narrative, and not found in any of the included psychosis narratives. “Recognition by diagnosis” was categorized under “Meaning in life”, which also explains the high presence of ‘Meaning in life’ in the autism narratives. Receiving an autism diagnosis after feeling misunderstood for years, or sometimes decades, seems to open doors to discover the authentic self. Narrators with a diagnosis of autism described this as being given recognition and a feeling of being treated seriously as a human being. Receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia, on the other hand, can have a devastating impact on one’s identity and limit future perspective (Guloksuz & van Os, Citation2019; Howe et al., Citation2014).

Our finding that personal recovery is a transdiagnostic concept is in line with previous studies (Jagfeld et al., Citation2021; Richardson & Barkham, Citation2020; Wetzler et al., Citation2020). We found that CHIME has transdiagnostic applicability that extends to people with autism and mood-related disorders, with some suggested nuances. Similarly, Wetzler et al. (Citation2020) found that CHIME fits well with eating disorder experiences, albeit with slightly different wording of Connectedness (named: “supportive relationships”) and with categorizing “self-compassion” as a separate dimension apart from CHIME instead of under “Identity”. In line with our findings regarding mood disorders, Richardson and Barkham (Citation2020) discussed that the CHIME dimensions fit depression narratives as well, but they did not test it against the CHIME codebook. Jagfeld et al. (Citation2021) found that CHIME is also relevant in people with bipolar disorder and propose some specific nuances for their patient group, with their most important suggestion being to add “Tensions” (i.e. Difficulties’) to the original framework. A study among Narcotics Anonymous (NA) members identified elements of CHIME and “Difficulties” in transcripts, which were all entwined with Connectedness, a crucial element in NA members (Dekkers et al., Citation2020). This finding accentuates the importance of the relational component in overcoming difficulties and overall recovery from addiction. It is important to notice, that still the biggest part of the content in the recovery narratives of our study is about ‘Difficulties’, such as hindering factors, ups- and downs, sometimes chronic character of difficulties, and how to overcome them in the process of overall recovery. Follow-up studies may focus on mapping distinctive categories of difficulties and identifying recovery-domain specific difficulties in recovery narratives.

In summary, our findings are in line with current literature supporting that the CHIME framework for personal recovery has transdiagnostic applicability, with only nuanced differences in categories, wording, and importance of certain dimensions between diagnoses. Of note: a cautious interpretation of our findings would be that all five CHIME domains appear to be present in narratives across all included diagnoses, not directly relating the quantitative representation of the frequencies to the importance of the individual CHIME domains. However, by applying the “inverse document frequency of codes” metric employed by Keller (Citation2017), it could be suggested that a high presence of certain CHIME domains in the narratives may be some indication of their importance to the narrators. Moreover, a recent study found that personal recovery and some associated factors can apply to the wider general population, indicating that personal recovery is a concept that suits us all, beyond the borders of mental illness (Van Eck et al., Citation2023).

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to test the transdiagnostic applicability of the CHIME framework across multiple diagnosis groups in one study using the original codebook of CHIME, and also the first to include recovery narratives about experiences of people with autism. Our results demonstrate similarities in personal recovery experiences between diagnoses, emphasizing the importance of a transdiagnostic approach in mental health care, but with subtle variations on (sub)category levels.

A limitation is that we did not have enough recovery narratives to reach saturation for (new) codes per diagnosis group. Future studies might test the fit of our preliminary expansion of the CHIME framework on a larger set of lived experiences narratives, to confirm or negate these seven additional (sub-)subcategories.

Clinical implications

This study once again shows that narratives about experiences across different diagnoses are full of personal recovery elements. Seven new personal recovery concepts have been identified to add to the CHIME framework of personal recovery processes. All these new concepts have relevance to clinical practice which could be explored. For example, the new code “Recognizing yourself in others & feeling connected to others” might draw attention to the need to support people in finding a community of others with similar experiences. Mental health care professionals might consider incorporating personal recovery goals in treatments of people with mental illness regardless of diagnosis. Effectiveness of mental health services may be improved by paying more attention to personal recovery from the start of treatment, since personal and clinical recovery are parallel instead of sequential processes (Castelein et al., Citation2021). Finally, we agree with the conclusion of Stuart et al. (Citation2017) and Van Weeghel et al. (Citation2019), that the difficulties and traumas people have experienced should not be ignored in the context of personal recovery. They coexist, as is emphasized by the substantial presence of “Difficulties” in the recovery narratives in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mariëtta Bulancea and Stijn Crutzen for coding narratives. We thank lived experience experts Albert Groenwold, Ewout Jager, Jorn Elzinga, and Sjoerd Steegstra for evaluating the newly assigned codes.

Disclosure statement

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Castelein, S., Timmerman, M. E., van der Gaag, M., & Visser, E. (2021). Clinical, societal and personal recovery in schizophrenia spectru disorders across time: States and annual transitions. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(1), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.48

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Davidson, L., & Strauss, J. S. (1992). Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1992.tb01693.x

- De Ruysscher, C., Vandevelde, S., Vanderplasschen, W., De Maeyer, J., & Vanheule, S. (2017). The concept of recovery as experienced by persons with dual diagnosis: A systematic review of qualitative research from a first-person perspective. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 13(4), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2017.1349977

- Deegan, P. E. (1988). Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 11(4), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099565

- Dekkers, A., Vos, S., & Vanderplasschen, W. (2020). "Personal recovery depends on NA unity": An exploratory study on recovery-supportive elements in Narcotics Anonymous Flanders. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00296-0

- Dell, N. A., Long, C., & Mancini, M. A. (2021). Models of mental health recovery: An overview of systematic reviews and qualitative meta-syntheses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 44(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000444

- Denzin, N. K. (1978). Sociological methods: A sourcebook. McGraw-Hill.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage.

- Guloksuz, S., & van Os, J. (2019). Renaming schizophrenia: 5 × 5. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(3), 254–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000586

- Hare-Duke, L., Charles, A., Slade, M., Rennick-Egglestone, S., Dys, A., & Bijdevaate, D. (2023). Systematic review and citation content analysis of the CHIME framework for mental health recovery processes: Recommendations for developing influential conceptual frameworks. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 6(1), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.33137/jrmh.v6i1.38556

- Howe, L., Tickle, A., & Brown, I. (2014). ‘Schizophrenia is a dirty word’: Service users’ experiences of receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The Psychiatric Bulletin, 38(4), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.113.045179

- Jagfeld, G., Lobban, F., Marshall, P., & Jones, S. H. (2021). Personal recovery in bipolar disorder: Systematic review and "best fit" framework synthesis of qualitative evidence - a POETIC adaptation of CHIME. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.051

- Jose, D., Ramachandra, n., Lalitha, K., Gandhi, S., Desai, G., & Nagarajaiah, n. (2015). Consumer perspectives on the concept of recovery in schizophrenia: A systematic review.Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 14, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.006

- Kapp, S. K., Gillespie-Lynch, K., Sherman, L. E., & Hutman, T. (2013). Deficit, difference, or both? autism and neurodiversity. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028353

- Keller, A. (2017). How to gauge the relevance of codes in qualitative data analysis? - A technique based on information retrieval. Wirtschaftsinformatik Und Angewandte Informatik. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/How-to-Gauge-the-Relevance-of-Codes-in-Qualitative-Keller/74288faede67cc1137f3f284350bc79843167144

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Lewis, L. F. (2016). Exploring the experience of self-diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(5), 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.03.009

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Llewellyn-Beardsley, J., Barbic, S., Rennick-Egglestone, S., Ng, F., Roe, J., Hui, A., Franklin, D., Deakin, E., Hare-Duke, L., & Slade, M. (2020). INCRESE: Development of an inventory to characterize recorded mental health recovery narratives. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 3(2), 25–44. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/rmh/article/view/34626.

- Müller, E., Schuler, A., & Yates, G. B. (2008). Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 12(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361307086664

- Richardson, K., & Barkham, M. (2020). Recovery from depression: A systematic review of perceptions and associated factors. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 29(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370629

- Silberman, S. (2015). Neurotribes: The legacy of autism and the future of neurodiversity. Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

- Slade, M. (2009). Personal recovery and mental illness: A guide for mental health professionals. Cambridge University Press.

- Stuart, S. R., Tansey, L., & Quayle, E. (2017). What we talk about when we talk about recovery: A systematic review and best-fit framework synthesis of qualitative literature. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 26(3), 291–304.

- Van Eck, R. M., van Velden, J., Vellinga, A., van der Krieke, L., Castelein, S., de Haan, L., Schirmbeck, F., van Amelsvoort, T., Bartels-Velthuis, A. A., Bruggeman, R., Cahn, W., Simons, C. J. P., & van Os, J. (2023). Personal recovery suits us all: A study in patients with non-affective psychosis, unaffected siblings and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Research, 255, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.02.026

- Van Sambeek, N., Baart, A., Franssen, G., van Geelen, S., & Scheepers, F. (2021). Recovering context in psychiatry: What contextual analysis of service users’ narratives can teach about recovery support. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 773856. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.773856

- Van Weeghel, J., van Zelst, C., Boertien, D., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2019). Conceptualizations, assessments, and implications of personal recovery in mental illness: A scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000356

- Wetzler, S., Hackmann, C., Peryer, G., Clayman, K., Friedman, D., Saffran, K., Silver, J., Swarbrick, M., Magill, E., van Furth, E. F., & Pike, K. M. (2020). A framework to conceptualize personal recovery from eating disorders: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of perspectives from individuals with lived experience. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(8), 1188–1203. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23260

Appendix 1.

Original CHIME codebook including newly assigned codes

NB. Newly assigned and additional codes used are displayed in bold.

Recovery processes

Category 1: Connectedness

1.1 Peer support and support groups

1.1.1 Availability of peer support

1.1.2 Becoming a peer support worker or advocate

1.2 Relationships

1.2.1 Building upon existing relationships

1.2.2 Intimate relationships

1.2.3 Establishing new relationships

1.3 Support from others

1.3.1 Support from professionals

1.3.2 Supportive people enabling the journey

1.3.3 Family support

1.3.4 Friends and peer support

1.3.5 Active or practical support

1.3.6. Support from an animal, pet, or assistance dog

1.4 Being part of the community

1.4.1 Contributing and giving back to the community

1.4.2 Membership of community organizations

1.4.3 Becoming an active citizen

1.5. Being seen as a person

Category 2: Hope and optimism about the future

2.1 Belief in possibility of recovery

2.2 Motivation to change

2.3 Hope-inspiring relationships

2.3.1 Role-models

2.4 Positive thinking and valuing success

2.5 Having dreams and aspirations

Category 3: Identity

3.1 Dimensions of identity

3.1.1 Culturally specific factors

3.1.2 Sexual identity

3.1.3 Ethnic identity

3.1.4 Collectivist notions of identity

3.2 Rebuilding/redefining positive sense of self

3.2.1 Self-esteem

3.2.2 Acceptance

3.2.3 Self-confidence and self-belief

3.3 Over-coming stigma

3.3.1 Self-stigma

3.3.2 Stigma at a societal level

3.4. Recognizing yourself in others / feeling connected to others

Category 4: Meaning in life

4.1 Meaning of mental illness experiences

4.1.1 Accepting or normalising the illness

4.1.2. Acknowledgement through diagnosis

4.1.3. Gaining self-insight

4.2 Spirituality (including development of spirituality)

4.3 Quality of life

4.3.1 Well-being

4.3.2 Meeting basic needs

4.3.3 Paid voluntary work or work-related activities

4.3.4 Recreational and leisure activities

4.3.5 Education

4.4 Meaningful social and life goals

4.4.1 Active pursuit of previous or new life or social goals

4.4.2 Identification of previous of new life or social goals

4.5 Meaningful life and social roles

4.5.1 Active pursuit of previous or new life or social roles

4.5.2 Identification of previous of new life or social roles

4.6 Rebuilding of life

4.6.1 Resuming with daily activities and daily routine

4.6.2 Developing new skills

4.6.3. Letting go of resentments, anger, or other negative emotions

Category 5: Empowerment

5.1 Personal responsibility

5.1.1 Self-management

Coping skills

Managing symptoms

Self-help

Resilience

Maintaining good physical health and well-being

5.1.2 Positive risk-taking

5.2 Control over life

5.2.1 Choice

Knowledge about illness

Knowledge about treatments

5.2.2 Regaining independence and autonomy

5.2.3 Involvement in decision-making

Care planning

Crisis planning

Goal setting

Strategies for medication

Medication not whole solution

5.2.4 Access to services and interventions

5.2.5. Distancing yourself from or shutting down unhealthy relationships

5.3 Focusing upon strengths

Category 6: Difficulties and Trauma

This category could be scored in this study, but is not part of the original CHIME framework.

Category 7: Not Relevant

This category could be scored in this study if the quotation was not related to CHIME dimensions (category: 1–5) or Difficulties (category: 6), e.g. place of birth.