Abstract

Background

Brief motivational coaching, integrated into health care; seems promising to address physical inactivity of people with serious mental illness (SMI).

Aims

To test the impact of a self-determined health coaching approach (the “SAMI” intervention) during outpatient mental health treatment on moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) of people with SMI.

Methods

Adults (mean age = 41.9, SD = 10.9) with an ICD-10 diagnosis of mental illness were semi-randomized to the SAMI-intervention group (IG) or control group (CG). The IG received 30 minutes of health coaching based on the self-determination theory (SDT). MVPA and sedentary time (ST) were measured with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – short form (IPAQ-SF) and symptoms of mental illness with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18), each at baseline and follow-up (3–4 months). Differences in primary (MVPA) and secondary (ST, BSI-18) outcomes were evaluated using negative binomial regressions and general linear models.

Results

In the IG (n = 30), MVPA increased from 278 (interquartile range [IQR] = 175–551) to 435 (IQR = 161–675) min/week compared to a decrease from 250 (IQR = 180–518) to 155 (IQR = 0–383) min/week in the CG (n = 26; adjusted relative difference at follow-up: Incidence Rate Ratio [IRR] = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.17–3.93, p = 0.014). There were no statistically significant differences in ST and BSI-18.

Conclusions

Brief self-determined health coaching during outpatient treatment could increase post-treatment MVPA in people with SMI, potentially up to a clinically relevant level. However, great uncertainty (for all outcomes) weakens the assessment of clinical relevance.

Introduction

Compared to the general population, people with serious mental illness (SMI) are at increased risk for inactivity and higher sedentary time (ST) (Schuch et al., Citation2017; Stubbs, Williams, et al., Citation2016; Vancampfort et al., Citation2016). There is also evidence showing a 53% higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and a 85% higher risk of death from CVD for people with SMI compared to the general population (Correll et al., Citation2017). Moreover, people with SMI experience an increased frequency of other common conditions of poor physical health, like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), poor dental status, obstetric complications and obesity due to a lack of preventative interventions (De Hert et al., Citation2011). However, high-quality evidence emphasizes the relevance of physical activity (PA) as a key lifestyle behavior for reducing these risks and improving not only physical but also mental health (Stubbs et al., Citation2018). The term PA refers to an array of bodily movements that result in energy expenditure (above a basal level). This definition includes activities in different domains: transport, domestic, occupational, and leisure. The term exercise (often considered as a part of leisure) specifically encompasses activities which are intentional, structured, repetitive with the goal to maintain and increase fitness and health (Caspersen et al., Citation1985). Related to that, especially PA of greater intensity has been shown to be beneficial for mental health. For instance, exercise improves positive and negative symptoms in people with schizophrenia (Firth et al., Citation2015) and reduces and prevents depressive symptoms in adults with depression (Brush & Burani, Citation2021). Moreover, moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) improves aerobic capacity and quality of life in people with SMI (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2014). Therefore, the European Psychiatric Association recommends 2–3 sessions of aerobic and/or aerobic and resistance training exercise a week of 45–60 minutes of moderate intensity (with the goal of achieving 150 minutes of MVPA per week) for improving (and treating) mental health problems of people with mild-moderate depression and at least 90–150 minutes of MVPA per week to improve symptoms among people with schizophrenia (Stubbs et al., Citation2018).

However, individuals with SMI face barriers to PA, including physical illness, poor general health, and, most significantly, lack of motivation (Farholm & Sørensen, Citation2016; Firth et al., Citation2016; Mishu et al., Citation2019; Romain, Bernard, et al., Citation2020) Consequently, it can be challenging for researchers and practitioners to reach out to people with SMI (Mishu et al., Citation2019). A promising way could be via institutions such as clinical treatment centers and other clinical settings (Stubbs et al., Citation2018), where barriers to participation are likely reduced since the promotion of PA is included in the daily routines of health care (Stanton et al., Citation2015).

Within these settings, brief counselling interventions, such as a 15 minutes motivational interviewing, could be an effective strategy for the treatment of physiological and psychological health problems (Rubak et al., Citation2005). Similar brief interventions have been carried out to increase PA in people with SMI. For example, Romain, Cadet, and Baillot (Citation2020) conducted a quasi-experimental pre-post study on a motivational intervention lasting for 5–10 minutes and a booster session after two weeks. The intervention was based on the transtheoretical model and included a volitional help sheet with “if-then” plans. The authors observed both an increase in PA and in the behavioral process of change among twelve male participants with psychosis. Sailer et al. (Citation2015) used a “Mental Contrasting and Implementation Intentions” (MCII) approach to improve exercising in in patients with schizophrenia. The intervention group consisted of participants allocated either to an autonomy-focused setting (where participants were not reminded to participate in a jogging session) or a highly structured setting (where participants were reminded to participate in a jogging session). Participants of the intervention group had to work through the MCII strategy, where they contrasted positive outcomes and obstacles of exercise, together with a therapist. To overcome these obstacles they were asked to write down if-then plans at three different times within three weeks to address typical problems of goal striving. As a result, people in the autonomy focused intervention group increased their attendance rate compared to the control group.

Theory-based interventions such as the above mentioned are recommended, as they are effective in PA promotion despite the presence of a disease (which is not a significant moderator of the efficacy), especially when all – rather than few (“inspired” by theory) – components of the theory are addressed (Bernard et al., Citation2017; Gourlan et al., Citation2016; Ntoumanis et al., Citation2018; Romain et al., Citation2018). For example, Farholm and Sørensen (Citation2016) also highlighted an urgent need for theory-based approaches to increase engagement in PA among people with SMI. Therefore, integrating such (motivational) theory-based interventions in real-world settings seems promising, which has also been recently recommended by Fibbins et al. (Citation2021).

The self-determination theory (SDT) is a popular theory in health promotion and behavior change (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), for which the application and relevance in PA has been clearly demonstrated (Ryan et al., Citation2009; Teixeira et al., Citation2012). The SDT represents a humanistic theory of behavior, which shares the notion that humans have a common drive to pursue fulfillment. Briefly, the theory proposes that we have a set of basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness) that, when met, lead to internal reward and intrinsic motivation (Rebar et al., Citation2021). While it seems that available theories of behavior change are equally effective (Gourlan et al., Citation2016), the rationale for selecting the SDT in the following study were manifold. First, it is well known that being unmotivated (amotivated), and being motivated because of external factors (e.g. going to the gym because “I have to” rather than “I want to”) are related to lower levels of PA, compared to being motivated based on inherent satisfaction (Ryan et al., Citation2009; Teixeira et al., Citation2012). Secondly, SDT takes into account the quality of motivation illustrated as different forms of motivation on a continuum. The main distinction can be made between autonomous types of motivation (e.g. finding personal meaning in your own behavior) and controlled types of motivation (e.g. pressure to adopt a certain behavior), whereas only autonomous motivation has a significant positive impact on behavioral and health outcomes (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000; Silva et al., Citation2014) Thirdly, interventions, which include the SDT, can yield to long-term changes of PA (Rhodes & Sui, Citation2021; Samdal et al., Citation2017). Finally, using the SDT can be crucial in the process of planning and implementing a PA intervention for people with SMI, because it can help to understand the reasons why people may or may not exercise (Fibbins et al., Citation2021).

Despite this knowledge, studies on the efficacy of brief PA counselling interventions in combination with the SDT are scarce (Farholm & Sørensen, Citation2016). Furthermore, despite Austrian PA guidelines suggest that effective programs should be built on behavior change techniques (Fonds Gesundes Österreich, Citation2020), studies on theory-based PA interventions in in- or outpatient treatment are missing in Austria. This also means that patients usually do not receive guidance on how to continue with PA after mental health treatment in Austria. Given this evidence, we designed the SAMI (“Stay Active with Mental Illness”) intervention, a self-determined motivational health coaching approach for people with SMI, in an outpatient treatment center. Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate (and inform about) the (potential) efficacy of this theory-based intervention, administered during ambulatory treatment, on increasing PA levels after stay.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This pilot-controlled trial was performed in an outpatient rehabilitation center for mental health in Graz, Austria. We recruited patients with SMI diagnosed according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health (World Health Organization, Citation2016); (e.g. schizophrenia [F20-F29]), affective disorders [F30-F39] and neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders [F40-F48]), who participated in a 6-week program of the rehabilitation center. The treatment usually involves medical care, psychotherapy, social work, occupational-, music-, physio- as well as exercise-therapy. All patients were able to return to their homes on a daily basis.

The recruitment period went from 1 February 2019, to 31 January 2020, and took place in the respective center. Adults of any gender, race/ethnicity and physical activity level were eligible for participation if they were aged 18–65 years, had a diagnosis of a SMI according to the ICD-10 standard and were assigned to the outpatient treatment. Exclusion criteria were medical contraindications for physical activity (e.g. acute psychosis) and inability to complete the questionnaire. Eligibility was examined by psychiatrists who were not involved in the study.

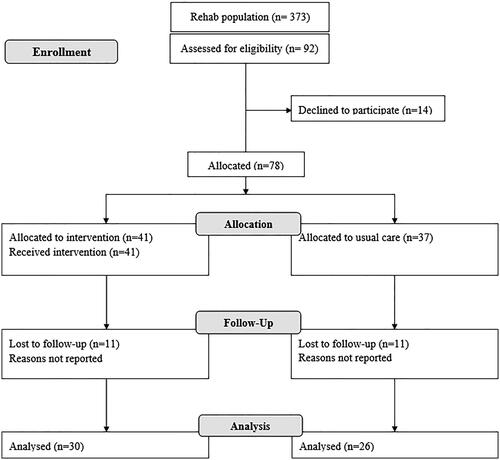

In 2017, 373 patients participated in the outpatient treatment program. It was assumed that about 50% (n = 186/year) of patients would be eligible and willing to participate in the study. We expected a dropout rate of about 40%–50% at follow-up (Göhner et al., Citation2015), and attempted to reach approximately 100 participants based on the available resources. Finally, 92 participants were recruited. The study was planned as a (pragmatic) pilot study to see if the intervention had positive effects on MVPA of our target group, as suggested previously (Eldridge et al., Citation2016).

The intervention took place in the 5th week of the 6-week program. The follow-up measurement was carried out 3–4 months after the beginning of the treatment. Outcomes (PA, symptoms of mental illness) were measured at baseline (beginning of treatment) and follow-up. In addition, demographic data of participants were routinely collected by psychologists at the beginning of the treatment.

At the beginning of their outpatient treatment, participants were semi-randomized to treatment groups through administrative staff, who did not meet the participants. This allocation depended neither on characteristics of the participants nor on the purpose of the study (i.e. evaluating the PA intervention). However, no strict randomization rule was applied. Instead, participants were assigned to groups based on availability of places. Two groups received the same 6-week program but started one week apart with different time schedules. The group that started first received the intervention in addition to the usual treatment, whereas the second group, which started one week later, formed the control group. PA coaches and investigators were not blinded throughout the study.

The study was registered at the German clinical trials register (DRKS-ID: DRKS00026097) and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Graz, Austria (GZ.39/18/63ex2018/19). All participants provided written informed consent. We followed the CONSORT standards for reporting.

Intervention

Our intervention was based on the SDT (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) which can be used to improve enjoyment of MVPA among people with SMI by identifying internal and external factors of motivation (Fibbins et al., Citation2021; Hoffmann et al., Citation2015). Participants of the intervention group received a 30-minute session with motivational interviewing by an exercise therapist, which included strategies from the 5 A’s behavior change model (Glasgow et al., Citation2002; Whitlock et al., Citation2002). The 5 A’s model is a tool to increase health behaviors, especially for underserved populations such as people with SMI (Carroll et al., Citation2012). Part of the coaching was the collaborative development of a personal action plan for each participant. For this, we followed the five concepts of ASSESSING believes, behaviors and knowledge about PA; ADVISE about health benefits and risks of being (more) physically active and the appropriate dose of PA; AGREE on collaboratively set goals; provide ASSISTANCE strategies such as social support and overcoming barriers; and ARRANGE a first individually tailed physical activity appointment at a sport club, or together with family members/friends outside the treatment center (real world setting). These strategies were used to improve the main components for autonomous motivation of the SDT.

Prior to the study, the exercise therapist received a briefing on the relationship between the 5A’s model and SDT. Trial consultations were conducted together with the exercise therapist to ensure a theory-based intervention. Moreover, the intervention occurred in the exercise therapist’s office, a familiar environment for the participants. This facilitated the creation of a supportive and motivational atmosphere. At the end of the session, the exercise therapist provided participants with a detailed plan that included goal setting and barrier management. The plan was taken home by the participants.

The SAMI intervention also considered the key techniques of need support (autonomy, competence, relatedness), as summarised by Silva et al. (Citation2014). A description with examples used in the intervention is provided in the Supplementary File. Overall, experiences made both during the face-to-face interview and while engaging in activities in real-world settings should increase intrinsic motivation and internalization (e.g. increasing interest/enjoyment, discovering a meaning or value of PA) and therefore, initiating behavior change (Ryan et al., Citation2009).

Primary and secondary outcomes

All participants were asked to complete the German version of the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF) (Craig et al., Citation2003; Lee et al., Citation2011), which assesses MVPA, walking and sitting time during the last seven days. Summarized minutes per week spent in MVPA represents the primary outcome variable.

Secondary outcomes included hours of ST/day and psychological and physical symptoms, which were measured using the German 18-items version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) (Derogatis, Citation2001), a short form of the 90-question Symptom Checklist SCL-90-R. The BSI-18 measures the subjectively perceived impairment by 18 physical and psychological symptoms over the last seven days on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = very strong). Four scales are mapped: depressiveness (DEP), anxiety (ANX), somatization (SOM) as well as the Global Severity Index (GSI). The latter represents the sum of the three primary dimensions (Spitzer et al., Citation2011). We used the GSI (total score), which was our main secondary outcome, to determine transdiagnostic symptom severity and overall psychological distress (Franke, Citation2000; Franke et al., Citation2017). The total score ranges from 0 to 72 points (range of each sub-score: 0–24 points). Higher scores indicate a higher symptom load. Results for the three sub-scores will be presented as well. Both questionnaires (IPAQ-SF, BSI-18) were administered electronically (via LimeSurvey) at baseline and follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented using median and interquartile range (IQR) for MVPA and ST, and mean and standard deviation for all other continuous variables (unless otherwise stated). We used t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests or Chi-square tests, to compare differences between groups (e.g. intervention vs control, study participants vs total population of treatment center), depending on the distribution of data and level of measurement. Associations of missingness at follow-up with baseline characteristics were assessed with binary logistic regression models.

The primary analysis was a multivariable negative binomial regression model for MVPA and ST and a general linear model for BSI. Negative binomial regression was chosen because MVPA and ST (expressed in integral units) were positively skewed and showed significant Poisson-overdispersion (Hilbe, Citation2011). The negative binomial model also resulted in a better fit compared to the Poisson model. Results are displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), using robust standard errors (Huber-White). IRRs (exponentiated negative binomial coefficients) reflect the relative rate of events over a specific period of time (e.g. MVPA minutes/week from participants of the intervention versus control group). All models were based on complete cases according to allocation (one participant moved from intervention to control group and was analyzed as participant of the intervention group) and were adjusted for age, gender and baseline outcomes.

Four sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of results. First, the primary analyses were repeated after excluding outliers (± 3SD away from the mean, Models S1). Secondly, the models were additionally (mutually) adjusted for baseline BSI/MVPA (Models S2) as well as follow-up measurement during a period with Covid-19 restrictions (yes/no, Models S3). From 16th of March 2020 to 1st of May 2020, people in Austria had to stay in their homes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sport and PA were only allowed at an individual level and all gyms, sports clubs (etc.) had to be closed. This effected 33 (59%) study participants, which had their follow-up after the start of the pandemic. Finally, differences in MVPA and ST between intervention and control group were also evaluated using general linear models (after excluding outliers, Models S4). The significance level was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided). The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28).

Results

Of the 92 participants asked, 78 (85%) agreed to take part in the study. All participants were considered eligible. At baseline, 37 participants were assigned to control and 41 to intervention group. The final sample included in the primary analyses consisted of 56 participants ().

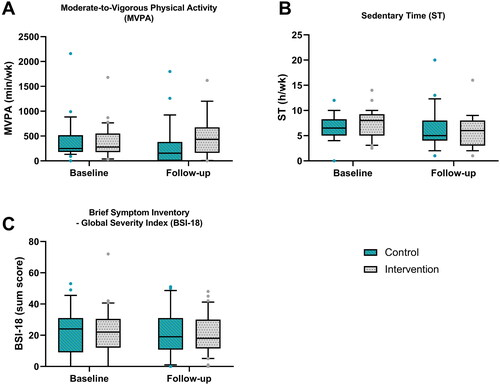

Baseline characteristics of all participants (n = 78) and of participants who completed the follow-up (n = 56, 72%) are shown in . Of all participants, the mean age was 41.9 years (standard deviation [SD] = 10.9), 52 (67%) were female and 49 (63%) were diagnosed with affective disorder, 26 (33%) with neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders, two (3%) with schizophrenia and one participant was diagnosed with an unspecific mental disorder (1%) (mean age of participants who completed follow-up was 40.9 years [SD = 10.9]). The total sample reported a median of 249.0 (IQR = 157.5–510.0) minutes of MVPA and 7.0 (IQR = 5.0–8.3) hours of ST per week. The mean BSI-18 score was 21.3 (SD = 24.0). Baseline characteristics were similar between intervention and control group (except age). Changes in outcomes (MVPA, ST, BSI-18) are displayed in .

Figure 2. Box plots of MVPA (A), ST (B) and the total score of BSI-18 (C) at baseline (beginning of treatment) and follow-up (3–4 months after beginning of treatment). Dots represent values below/above the 10th/90th percentiles.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

Study participants were similar to the total outpatient treatment population (N = 666 patients, who underwent treatment in 2018/2019) regarding gender, ICD-10 diagnosis, age, BSI-18 and planned work conditions of participants after outpatient treatment (Supplementary Table S1). Twenty-two participants (28%) did not complete the follow-up measurement. Missingness at follow-up was statistically not associated with baseline characteristics or group assignment (Supplementary Table S2).

Primary outcome

In the intervention group, MVPA increased from 278 (IQR = 175–551) to 435 (IQR = 161–675) min/week compared to a decrease from 250 (IQR = 180–518) to 155 (IQR = 0–383) min/week in the control group. Compared to the control group, participants from the intervention group reported 114% more weekly minutes of MVPA at follow-up (IRR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.17 to 3.93, p = 0.014, ).

Table 2. Primary analyses of outcomes (MVPA, ST, BSI-18) at follow-up (3–4 months after beginning of treatment).

Secondary outcomes and sensitivity analysis

Results for secondary outcomes are presented in . ST decreased from 8.0 (IQR = 5.0–9.3) to 6.0 (IQR = 180–480) h/day in the intervention group and from 6.5 (IQR = 5.0–8.3) to 5.0 (IQR = 4.0–8.0) h/day in the control group (adjusted relative difference at follow-up: IRR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.60–1.10, p = 0.171).

There was no statistically significant difference in symptoms related to mental illness between intervention group, where BSI-18-Total declined from 21.9 (SD = 15.5) to 20.9 (SD = 12.5) points, and control group, where BSI-18-Total declined from 21.6 (SD = 15.6) to 21.5 (SD = 15.2) points (adjusted mean-difference at follow-up = −0.72, 95% CI: −8.21 to 6.77, p = 0.847).

Sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table S3) showed similar, but sometimes larger effects (e.g. IRR = 2.46, 95% CI: 1.35–4.50, for MVPA at follow-up when adjusting for Covid-19, IRR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.47–5.12, for MVPA at follow-up after excluding outliers).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot intervention study in Austria that examined changes in PA among people with SMI through motivational health coaching, integrated into the routine of outpatient mental health treatment. We observed statistically significant differences in MVPA (primary outcome) and no statistically significant differences in ST and BSI-18 (secondary outcomes) between intervention and control group at follow-up.

To date, there exist no definite thresholds for minimal clinically important differences in MVPA in people with SMI. Even brief interventions (e.g. 2 × 16 min cycling for 6 weeks) could be beneficial for improving psychiatric symptoms (Herring et al., Citation2014; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2014), but more evidence is available for interventions of longer duration, which are usually informed by PA guidelines. For example, the European Psychiatric Association recommends 45–60 minutes of moderate aerobic and/or aerobic and resistance training, performed over 2–3 sessions a week, for treating mild-moderate depression (Stubbs et al., Citation2018). Based on this evidence and the continuous relationship between PA and (mental) health (“every step counts”) (Powell et al., Citation2018), a difference in MVPA (including lower and upper limit of the 95% CI), such as the one observed in our study, could be seen as (at least “probable”) clinically relevant for the target population (Man-Son-Hing et al., Citation2002). However, even though the present study may provide evidence against very small improvements in MVPA (i.e. < 17%), any improvement from 17% to 293% is compatible with the data, which leaves us with considerable uncertainty regarding effect sizes (Greenland et al., Citation2022).

Compared to previous studies conducted with people with SMI in outpatient treatment settings, differences in MVPA were similar but sometimes larger in our study. For example, Göhner et al. (Citation2015) evaluated the influence of the “MoVo–Luise” intervention (consisting of group and individual sessions, telephone coaching, self-monitoring) among 65 patients receiving inpatient psychosomatic rehabilitation. In this study, participants in the intervention group reported 95 min/week more exercise at 6-months follow-up than participants in the control group. Williams et al. (Citation2019) investigated in their pilot study the impact of a 17-week intervention (“Walk this Way”), delivered within a community mental health team, on device-based measured MVPA (secondary outcome). People with SMI receiving this intervention showed greater levels of MVPA, even at 6-months follow-up (e.g. 187 vs. 110 min/day). Similar results, even though not significant, were reported by Druss et al. (Citation2010), who measured the impact of up to six group sessions, led by mental health peer specialists, on self-reported MVPA of people with SMI. MVPA of the intervention group increased from 150 to 191 min/week and decreased from 154 to 152 min/week in the control group.

There are several possible reasons for the observed intervention effects. Firstly, we chose a person-centered coaching approach with all components of the SDT (competence, relatedness & autonomy). The intervention was based on participants’ PA preferences and motives for participation (Fibbins et al., Citation2021) and therefore could have had a positive effect on PA (Delli Paoli, Citation2021; Romain & Bernard, Citation2018). Secondly, the setting of an ambulatory treatment enabled engagement in MVPA outside of the treatment center, namely in patients’ real-world setting (Fibbins et al., Citation2021; Romain & Bernard, Citation2018; Schebesch-Ruf et al., Citation2019). For example, some participants may have already started to participate in sport club activities in the afternoon/evening (following outpatient treatment).

Regarding secondary outcomes, we observed no statistically significant difference in ST between intervention and control group at follow-up. This may be simply caused by the fact that reducing ST was not the primary aim of our health coaching approach. Until now, there is inconsistent and low-quality evidence whether interventions can be effective in reducing ST (Ashdown-Franks et al., Citation2018). Moreover, ST and PA have distinct features which may require holistic interventions in order to address these and any potential time allocation effects between different (movement) behaviors (e.g. increasing ST, as a compensation, because of increasing MVPA) (Hartman et al., Citation2020; Manini et al., Citation2015). Therefore, since ST is associated with mental health (Smith et al., Citation2018), it will be crucial to design coaching sessions to target also high ST, such as the “Walk this Way” intervention developed by Williams et al. (Citation2019). Finally, there was no statistically significant difference in symptom severity between intervention and control group at follow-up. One possible explanation could be that the myriad of multidisciplinary treatments conducted during the stay improved psychological symptoms of both intervention and control group. This effect was described as challenge for examining the efficacy of PA on depressive symptoms since the PA intervention needs to outperform control “interventions” rather than traditional placebo responses (Stubbs, Vancampfort, et al., Citation2016). On the other side, while there was a lack of statistical significance for ST and BSI-18, the results leave us with great uncertainty in terms of effect sizes. For ST, the results are most compatible with any effect from 40% lower and 10% higher ST in the intervention group. One may assume clinically relevant changes in ST (e.g. 5–10% of average daily ST) to be within this interval. Thus, our results would be indecisive and may only provide evidence against large reductions in ST (i.e. > 40%). Similar rather imprecise estimates were evident for BSI-18. Therefore, this study may not have definite answers for clinical relevance in this regard (which is in line with the design of a "pilot" study).

This study had several strengths. A strength of our study is the relatively brief and low-cost intervention which could be easily implemented into the daily routine of health care settings. Also, the study group is representative for the total population treated in the respective center and, hence, the results may be generalizable and transferable to the majority of people with SMI in outpatient treatment in Austria. However, we also need to acknowledge the limitations. First, we could not carry out a second follow-up measurement one year after outpatient treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, we were not able to assess the possible development of a long-term strategy to maintain a sufficient level of MVPA, as suggested by Ashdown-Franks et al. (Citation2018) and Verhaeghe et al. (Citation2013). Furthermore, the intervention consisting of one coaching session of 30 minutes may have been not effective enough to considerably affect symptoms of mental disorders. Another limitation of this study is the self-reported PA questionnaire (IPAQ-SF), as it tends to overestimate MVPA in people with SMI (Firth et al., Citation2018) and generally may not be sufficiently responsive to change in MVPA (Bauman et al., Citation2009). Moreover, social desirability is associated with overreporting MVPA (Adams et al., Citation2005) and people with SMI can have difficulties to recall their MVPA behavior (Soundy et al., Citation2014; Stubbs, Firth, et al., Citation2016). Also, participants in the current study could be considered as rather active (e.g. around 250 minutes of MVPA per week at baseline), but other studies, such as Williams et al. (Citation2019), reported even higher levels of objectively measured MVPA in people with SMI (e.g. around 100–180 minutes of MVPA per day). These higher activity levels must be taken into account when generalizing the results to other populations. Also, the present study was planned as a pilot study involving a small sample of participants. Small samples reduce the probability of discovering true effects while simultaneously suffering from effect inflation and higher proportion of false positives (Bernard et al., Citation2017; Button et al., Citation2013). Hence, we were only able to detect relatively large differences between groups and future confirmatory trials with sufficient statistical power are needed. Such trials can also help in the detection of any effect modification, for example due to differences in (prior) baseline PA level. Finally, the lack of a strict randomization procedure may have introduced bias in estimating the treatment effect through (unobserved) confounding. However, using available data, we have performed several sensitivity analyses yielding to similar results.

Conclusion

A brief theory-based motivational coaching session supported people with SMI to increase PA after psychiatric outpatient treatment. The intervention may even evoke clinically relevant changes in MVPA, even though a great range of effect sizes were compatible with the data. Therefore, the integration of such brief coaching sessions into daily routine of outpatient mental health care could be useful. A lack of statistical significance was observed for ST and symptom severity (BSI-18) but there was also considerable uncertainty, making it difficult to establish the direction and clinical relevance of the effect. To overcome shortcomings of this pilot trial, a larger randomized controlled trial with long-term follow-up measurements is needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (39.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, S. A., Matthews, C. E., Ebbeling, C. B., Moore, C. G., Cunningham, J. E., Fulton, J., & Hebert, J. R. (2005). The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(4), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi054

- Ashdown-Franks, G., Williams, J., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Schuch, F. B., Hubbard, K., Craig, T., Gaughran, F., & Stubbs, B. (2018). Is it possible for people with severe mental illness to sit less and move more? A systematic review of interventions to increase physical activity or reduce sedentary behaviour. Schizophrenia Research, 202, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.058

- Bauman, A. E., Ainsworth, B. E., Bull, F., Craig, C. L., Hagströmer, M., Sallis, J. F., Pratt, M., & Sjöström, M. (2009). Progress and pitfalls in the use of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for adult physical activity surveillance. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 6(s1), S5–S8. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.6.s1.s5

- Bernard, P., Carayol, M., Gourlan, M., Boiché, J., Romain, A. J., Bortolon, C., Lareyre, O., & Ninot, G. (2017). Moderators of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity in 77 randomized controlled trials. Health Education & Behavior, 44(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116648667

- Brush, C. J., & Burani, K. (2021). Exercise and physical activity for depression. In Z. Zachary & J. Leighton (Eds.), Essentials of exercise & sport psychology: An open textbook (pp. 338–368). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology.

- Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 14(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475

- Carroll, J. K., Fiscella, K., Epstein, M., Sanders, M. R., & Williams, G. (2012). A 5A’s communication intervention to promote physical activity in underserved populations. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 374. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-374

- Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 126–131. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3920711/

- Correll, C. U., Solmi, M., Veronese, N., Bortolato, B., Rosson, S., Santonastaso, P., Thapa-Chhetri, N., Fornaro, M., Gallicchio, D., Collantoni, E., Pigato, G., Favaro, A., Monaco, F., Kohler, C., Vancampfort, D., Ward, P. B., Gaughran, F., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2017). Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20420

- Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjöström, M., Bauman, A. E., Booth, M. L., Ainsworth, B. E., Pratt, M., Ekelund, U., Yngve, A., Sallis, J. F., & Oja, P. (2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(8), 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

- De Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, DAN., Asai, I., Detraux, J., Gautam, S., Möller, H.-J., Ndetei, D. M., Newcomer, J. W., Uwakwe, R., & Leucht, S. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 10(1), 52–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x 21379357

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

- Delli Paoli, A. G. (2021). Predictors and correlates of physical activity and sendetary behaviour. In Z. Zachary & J. Leighton (Eds.), Essentials of exercise & sport psychology: An open textbook (pp. 93–113). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology.

- Derogatis, L. R. (2001). BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. NCS Pearson.

- Druss, B. G., Zhao, L., von Esenwein, S. A., Bona, J. R., Fricks, L., Jenkins-Tucker, S., Sterling, E., Diclemente, R., & Lorig, K. (2010). The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: A peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Research, 118(1–3), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: Development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One, 11(3), e0150205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Farholm, A., & Sørensen, M. (2016). Motivation for physical activity and exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review of intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(3), 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12214

- Fibbins, H., Lederman, O., & Rosenbaum, S. [. (2021). Physical activity and severe mental illness. In Z. Zachary & J. Leighton (Eds.), Essentials of exercise & sport psychology: An open textbook (pp. 385–408). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology.

- Firth, J., Cotter, J., Elliott, R., French, P., Yung, A. R., & Alison, R. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychological Medicine, 45(7), 1343–1361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714003110

- Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Gorczynski, P., Yung, A. R. & Vancampfort, D. (2016). Motivating factors and barriers towards exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2869–2881. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001732

- Firth, J., Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Schuch, F. B., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., Firth, J. A., Sarris, J., & Yung, A. R. (2018). The validity and value of self-reported physical activity and accelerometry in people with Schizophrenia: A population-scale study of the UK Biobank. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(6), 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx149

- Fonds Gesundes Österreich (Ed.). (2020). Österreichische Bewegungsempfehlungen. Wissensband. 17.

- Franke, G. H. (2000). BSI. Brief symptom inventory – Deutsche Version. Manual. Beltz.

- Franke, G. H., Jaeger, S., Glaesmer, H., Barkmann, C., Petrowski, K., & Braehler, E. (2017). Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0283-3

- Glasgow, R. E., Funnell, M. M., Bonomi, A. E., Davis, C., Beckham, V., & Wagner, E. H. (2002). Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(2), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_04

- Göhner, W., Dietsche, C., & Fuchs, R. (2015). Increasing physical activity in patients with mental illness – A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(11), 1385–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.006

- Gourlan, M., Bernard, P., Bortolon, C., Romain, A. J., Lareyre, O., Carayol, M., Ninot, G., & Boiché, J. (2016). Efficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychology Review, 10(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.981777

- Greenland, S., Mansournia, M. A., & Joffe, M. (2022). To curb research misreporting, replace significance and confidence by compatibility: A Preventive Medicine Golden Jubilee article. Preventive Medicine, 164, 107127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107127

- Hartman, S. J., Pekmezi, D., Dunsiger, S. I., & Marcus, B. H. (2020). Physical activity intervention effects on sedentary time in spanish-speaking Latinas. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 17(3), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0112

- Herring, M. P., O’Connor, P. J., & Dishman, R. K. (2014). Self-esteem mediates associations of physical activity with anxiety in college women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(10), 1990–1998. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000323

- Hilbe, J. M. (2011). Negative binomial regression (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511973420

- Hoffmann, K. D., Walnoha, A., Sloan, J., Buddadhumaruk, P., Huang, H., H., Borrebach, J., Cluss, P. A., & Burke, J. G. (2015). Developing a community-based tailored exercise program for people with severe and persistent mental illness. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: research, Education, and Action, 9(2), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2015.0045

- Lee, P. H., Macfarlane, D. J., Lam, T. H., & Stewart, S. M. (2011). Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-115

- Manini, T. M., Carr, L. J., King, A. C., Marshall, S., Robinson, T. N., & Rejeski, W. J. (2015). Interventions to reduce sedentary behavior. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47(6), 1306–1310. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000519

- Man-Son-Hing, M., Laupacis, A., O’Rourke, K., Molnar, F. J., Mahon, J., Chan, K. B. Y., & Wells, G. (2002). Determination of the clinical importance of study results. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17(6), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11111.x

- Mishu, M. P., Peckham, E. J., Heron, P. N., Tew, G. A., Stubbs, B., & Gilbody, S. (2019). Factors associated with regular physical activity participation among people with severe mental ill health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(7), 887–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1639-2

- Ntoumanis, N., Thørgersen-Ntouman, C., Quested, E., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2018). Theoretical Approaches to Physical Activity Promotion. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.

- Powell, K. E., King, A. C., Buchner, D. M., Campbell, W. W., DiPietro, L., Erickson, K. I., Hillman, C. H., Jakicic, J. M., Janz, K. F., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Kraus, W. E., Macko, R. F., Marquez, D. X., McTiernan, A., Pate, R. R., Pescatello, L. S., & Whitt-Glover, M. C. (2018). The Scientific foundation for the physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2018-0618

- Rebar, A. L., Alfrey, K. L., & Gardner, B. (2021). Theories of physical activity motivation. In Z. Zenko & L. Jones (Eds.), Essentials of exercise and sport psychology: An open access textbook (pp. 15–36). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology.

- Rhodes, R. E., & Sui, W. (2021). Physical Activity Maintenance: A Critical Narrative Review and Directions for Future Research. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 725671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725671

- Romain, A. J., & Bernard, P. (2018). Behavioral and psychological approaches in exercise-based interventions in severe mental illness. In B. Stubbs & S. Rosenbaum (Eds.), Exercise-based interventions for mental illness: Physical activity as part of clinical treatment/brendon stubbs and simon rosenbaum. Academic Press.

- Romain, A. J., Bernard, P., Akrass, Z., St-Amour, S., Lachance, J., P., Hains-Monfette, G., Atoui, S., Kingsbury, C., Dubois, E., Karelis, A. D., & Abdel-Baki, A. (2020). Motivational theory-based interventions on health of people with several mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 222, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.049

- Romain, A. J., Bortolon, C., Gourlan, M., Carayol, M., Decker, E., Lareyre, O., Ninot, G., Boiché, J., & Bernard, P. (2018). Matched or nonmatched interventions based on the transtheoretical model to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 7(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.10.007

- Romain, A. J., Cadet, R., & Baillot, A. (2020). Brief theory-based intervention to improve physical activity in men with psychosis and obesity: A feasibility study. Science of Nursing and Health Practices, 3(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.31770/2561-7516.1084

- Rosenbaum, S., Simon, A., Sherrington, C., Curtis, J., Ward, P. B., & Tiedemann, P. B. (2014). Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(9), 964–974. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13r08765

- Rubak, S., Sandbaek, A., Lauritzen, T., & Christensen, B. (2005). Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of General Practice, 55(513), 305–312.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., Williams, G., Patrick, H., & Deci, E. L. (2009). Self-determination theory and physical activity: The dynamics of motivation in development and wellness. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 6(2), 107–124.

- Sailer, P., Wieber, F., Pröpster, K., Stoewer, S., Nischk, D., Volk, F., & Odenwald, M. (2015). A brief intervention to improve exercising in patients with schizophrenia: A controlled pilot study with mental contrasting and implementation intentions (MCII). BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0513-y

- Samdal, G. B., Eide, G. E., Barth, TOM., Williams, G., & Meland, E. (2017). Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 42.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y

- Schebesch-Ruf, W., Heimgartner, A., Wells, J. S., & Titze, S. (2019). A qualitative examination of the physical activity needs of people with severe mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(10), 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1610818

- Schuch, F., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S. [., Simon, P., Reichert, T., Bagatini, N. C., Bgeginski, R., Stubbs., & Ward, P. B. (2017). Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.050

- Silva, M. N., Marques, M. M., & Teixeira, P. J. (2014). Testing theory in practice: The example of self-determination theory-based interventions. European Health Psychologist, 16(5), 171–180.

- Smith, L., Hamer, M., & Gardner, B. (2018). Sedentary behaviour and mental health. In B. Stubbs & S. Rosenbaum (Eds.), Exercise-based interventions for mental illness: Physical activity as part of clinical Treatment/Brendon Stubbs and Simon Rosenbaum. Academic Press.

- Soundy, A., Roskell, C., Stubbs, B., & Vancampfort, D. (2014). Selection, use and psychometric properties of physical activity measures to assess individuals with severe mental illness: A narrative synthesis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.12.002

- Spitzer, C., Hammer, S., Löwe, B., Grabe, H. J., Barnow, S., Rose, M., Wingenfeld, K., Freyberger, H. J., & Franke, G. H. (2011). Die Kurzform des Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18): erste Befunde zu den psychometrischen Kennwerten der deutschen Version [The short version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18): preliminary psychometric properties of the German translation]. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie, 79(9), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1281602

- Stanton, R., Reaburn, P., & Happell, B. (2015). Barriers to exercise prescription and participation in people with mental illness: the perspectives of nurses working in mental health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(6), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12205 25855247

- Stubbs, B., Rosenbaum, S. (2018). Introduction. In: B. Stubbs & S. Rosenbaum (Eds.), Exercise-Based Interventions for Mental Illness: Physical Activity as Part of Clinical Treatment (pp. 19–23). Elsevier Ltd.: Academic Press.

- Stubbs, B., Firth, J., Berry, A., Schuch, F. B., Rosenbaum, S. , Simon, F., Veronesse, N., Williams, J., Craig, T., Yung, A. R., Gaughran, D., & Vancampfort, A. R. (2016). How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophrenia Research, 176(2-3), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Hallgren, M., Firth, J., Veronese, N., Solmi, M., Brand, S., Cordes, J., Malchow, B., Gerber, M., Schmitt, A., Correll, C. U., de Hert, M., Gaughran, F., Schneider, F., Kinnafick, F., Falkai, P., Möller, H., J., & Kahl, K. G. (2018). Epa guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: A meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). European Psychiatry, 54, 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S., Simon, P. B., Richards, J., Ussher, M., Schuch., & Ward, F. B. (2016). Challenges establishing the efficacy of exercise as an antidepressant treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of control group responses in exercise randomised controlled trials. Sports Medicine, 46(5), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0441-5

- Stubbs, B., Williams, J., Gaughran, F., & Craig, T. (2016). How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 171(1–3), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.034

- Teixeira, P. J., Carraça, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

- Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Schuch, F., Rosenbaum, S., Hert, M., de Mugisha, J., Probst, M., & Stubbs, B., (2016). Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.020

- Verhaeghe, N., Clays, E., Vereecken, C., de Maeseneer, J., Maes, L., van Heeringen, C., de Bacquer, D., & Annemans, L. (2013). Health promotion in individuals with mental disorders: A cluster preference randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 657. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-657

- Whitlock, E. P., Orleans, C. T., Pender, N., & Allan, J. (2002). Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions an evidence-based approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22(4), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00415-4

- Williams, J., Stubbs, B., Richardson, S., Flower, C., Barr-Hamilton, L., Grey, B., Hubbard, K., Spaducci, G., Gaughran, F., & Craig, T. (2019). Walk this way’: Results from a pilot randomised controlled trial of a health coaching intervention to reduce sedentary behaviour and increase physical activity in people with serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 287. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2274-5

- World Health Organization. (2016). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. (10th ed.). WHO.