Abstract

Background

Self-compassion (SC), reflecting self-attitude and self-connectedness, has proven to be a modifiable factor in promoting mental health outcomes. Increasingly, SC is recognized as a multidimensional construct consisting of six dimensions, rather than a single dimension.

Objectives

First, this study adopted a person-centered approach to explore profiles of SC dimensions in Chinese young adults. Second, the study examined the predictive effects of SC profiles on mental health outcomes.

Methods

In February 2020, young adults (N = 1164) were invited to complete the 26-item Neff’s Self-Compassion Scale online. Three months later, the same subjects (N = 1099) reported their levels of depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and posttraumatic growth (PTG).

Results

After controlling for retrospective ACEs, four classes best characterized the profiles: self-compassionate (26.7%, N = 294), self-uncompassionate (12.3%, N = 135), average (55.9%, N = 614), and detached groups (5.1%, N = 56). Young adults in the self-compassionate group adjusted the best (with the highest level of PTG and the lowest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms). Adults in the self-uncompassionate group demonstrated the poorest mental health outcomes (with the lowest level of PTG and the highest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms). Young adults in the average group obtained more PTG than adults in the detached group (p < .01), but did not differ significantly in depressive and PTSD symptoms (p > .05).

Conclusion

The compassionate profile is the most adaptable for young adults among all groups. This study highlights the limitations of representing the relative balance of SC with a composite score.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exerted significant global impacts and caused widespread mental health effects, including depressive symptoms (Li, Wang, et al., Citation2021; Li, Zhao, et al., Citation2021; Rudenstine et al., Citation2021; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Chi et al., Citation2020; Karatzias et al., Citation2020; Murata et al., Citation2021; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic swiftly swept across the globe, resulting in a significant number of fatalities and illnesses, and presenting a major global public health crisis (North et al., Citation2021; Ochnik et al., Citation2021; Shevlin et al., Citation2020). Many individuals worldwide have likely felt threatened and horrified by the existential threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which researchers emphasize can be considered a traumatic event (Shevlin et al., Citation2020; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022). Considering as a traumatic experience, the COVID-19 pandemic had the potential to generate pervasive mental health outcomes, particularly PTSD symptoms (Forte et al., Citation2020; C. H. Liu et al., Citation2020; Ochnik et al., Citation2021; Shek et al., Citation2021; Tang et al., Citation2020). Hence, under the context of the pandemic, it is meaningful to investigate PTSD symptoms in young adults (Chi et al., Citation2020; Ochnik et al., Citation2021; Xiong et al., Citation2020; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022). Moreover, individuals with PTSD symptoms were found to be several times more likely to experience psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depressive symptoms (Karatzias et al., Citation2020; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022). One recent study by Zhen and Zhou (Citation2022) revealed that PTSD and depressive symptoms tend to coexist in a similar pattern during the pandemic. Overall, PTSD and depression were two common psychopathologies observed in individuals following exposure to COVID-19 (Vindegaard & Benros, Citation2020; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022). Notably, limited studies during the pandemic have shown that individuals not only experienced PTSD symptoms but also reported varying levels of posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Tomaszek & Muchacka-Cymerman, Citation2020). Posttraumatic growth refers to positive psychological changes that occur after individuals experience a traumatic event or adversity, involving personal growth, increased resilience, and a greater appreciation for life (A. Liu et al., Citation2021b; A. Liu et al., Citation2023). The pandemic, as a potential traumatic event (North et al., Citation2021; Shevlin et al., Citation2020; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022), may trigger a series of circumstances that shatter the fundamental cognitive assumptions of individuals, posing challenges to their understanding of the world (Tomaszek & Muchacka-Cymerman, Citation2020). This, in turn, may set the stage for the development of PTG (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004; Tedeschi et al., Citation2007). Therefore, it is meaningful to pay attention to PTSD, depressive symptoms, and PTG in young Chinese adults during the pandemic.

During this challenging period, it is particularly important to probe the problem of how individuals connected and related to themselves during the home quarantine period and the influence on their mental health (Li, Wang, et al., Citation2021; Li, Zhao, et al., Citation2021). Through interacting with the world, self-compassion (SC) could decrease the level of negative mental health outcomes (Berryhill & Smith, Citation2021) and facilitate positive outcomes (Li, Wang, et al., Citation2021; Li, Zhao, et al., Citation2021), such as PTG. As an important psychological competence, SC has been acknowledged to be multidimensional, including three components of six opposing dimensions: self-kindness, self-judgments, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and overidentification (Neff et al., Citation2019). But to date, little attention has been paid to how different opposing dimensions operate together within individuals influencing their mental health outcomes longitudinally. The study used a person-centered approach to identify different SC dimensions and combination patterns. Additionally, the study used a longitudinal design to examine the relationships between these SC profiles and positive (PTG) and negative mental health outcomes (depressive and PTSD symptoms).

The impact of self-compassion on psychological adjustments amidst the pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, college students experienced disruptions to their college life due to control measures implemented (S. Liu et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2023). Confined to their homes and isolated from peer interactions, college students faced concerns about infection and loneliness, potentially affecting their psychological well-being negatively (S. Liu et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2023). In this context, how college students connected with themselves and navigated their experiences of suffering became crucial for psychological well-being (Chi et al., Citation2022; Liang et al., Citation2022). Self-compassion emerged as a catalyst, encouraging students to approach themselves and the world with kindness and mindfulness (Huang et al., Citation2023; Liang et al., Citation2022), fostering a balanced attitude toward both themselves and their emotional responses in challenging circumstances (Berryhill & Smith, Citation2021; Krieger et al., Citation2016). High SC reflects a healthy and adaptive relationship with oneself, which can help alleviate negative emotions and facilitate psychological growth (Neff, Citation2003a; Neff et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Research conducted during the pandemic highlighted SC’s positive role in fostering coping mechanisms, enhancing life satisfaction (Li, Wang, et al., Citation2021; Li, Zhao, et al., Citation2021), and reducing emotional distress during lockdown measures (Gutiérrez-Hernández et al., Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2023; Liang et al., Citation2022). Consequently, exploring the impact of SC on the psychological adjustments holds significant meaning during the pandemic.

The multidimensional structure of SC

By promoting healthy, balanced, and adaptive connections to oneself and the world, SC could alleviate negative emotions during quarantine (Gutiérrez-Hernández et al., Citation2022) and improve life satisfaction (Li, Wang, et al., Citation2021; Li, Zhao, et al., Citation2021). The framework of SC contains three opposing components, which include six separate dimensions (Neff, Citation2003a, Citation2003b, Citation2016; Neff et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). The first component concerns self-kindness, reflecting unconditional acceptance and care toward oneself, with self-judgment as the opposing dimension, describing criticism and intolerance about the inadequacy and imperfections in oneself. The second component is common humanity, which views one’s suffering as common human experiences rather than feelings of isolation as the opposing dimension. The third component is mindfulness, referring to experience present thoughts and feeling in a balanced way instead of overidentification as the opposing dimension, which contains repressing, denying, or overidentifying thoughts and feelings (Neff, Citation2003a, Citation2003b, Citation2016; Neff et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

The present empirical studies have mainly utilized the total score of SC to investigate its associations with mental health outcomes (Berryhill & Smith, Citation2021; Krieger et al., Citation2016). By reverse coding the negative dimension scores, researchers could achieve the relative balance of opposing dimensions. However, this approach may obscure the relative importance of individual opposite dimensions for mental health. For example, the composite score precluded us from exploring how an individual factor self-responded on each bipolar dimension (Neff, Citation2003a, Citation2003b, Citation2016). Some researchers have proposed that the reverse coding approach might lead to an overestimation of the associations between positive SC and negative mental health indicators (Muris & Petrocchi, Citation2017). In this way, they advocated using two positive and negative scores to treat SC from a two-dimensional perspective. In response, researchers (Neff et al., Citation2019) have reexamined the structure of SC. The results did not provide empirical support for using two distinguished positive and negative scores separately, but rather the advantages of using six-dimensional scores.

Only a few studies have used dimension scores to examine the links with different mental health indicators (Bluth & Blanton, Citation2015; Shin & Lim, Citation2019; Sun et al., Citation2016). Limited empirical studies have indicated the diverse impacts of different SC dimensions on psychological adjustment outcomes (Rahmati Kankat et al., Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2016; Wong & Yeung, Citation2017). In one prior study (Sun et al., Citation2016), researchers found that significant effects primarily emerged from self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness concerning adolescents’ psychological well-being. Another study (Bluth & Blanton, Citation2015) found that isolation demonstrated the most consistent and strongest relationships with negative mood, perceived stress and life satisfaction in adolescents. Additionally, another study (Wong & Yeung, Citation2017) revealed no significant associations between negative SC and PTG after accounting for positive SC dimensions. However, these studies adopted the variable-centered approach to separately examine the associations between each dimension and its mental health outcomes (Bluth & Blanton, Citation2015; Shin & Lim, Citation2019; Sun et al., Citation2016). The variable-centered analysis is designed to assess how specific variables, both separately and in interaction, are related to other variables (Elhami Athar, Citation2023; van Aar et al., Citation2019). The traditional and dominant variable-centered approach can explain the relationships between the variables of interest (Gillet et al., Citation2018; Howard & Hoffman, Citation2017; van Aar et al., Citation2019), which is suitable for investigating research questions and hypotheses about the effects of one variable on another within the entire population (Gillet et al., Citation2018; Howard & Hoffman, Citation2017). Therefore, the variable-centered approach assumes individual heterogeneity, with the associations exhibiting considerable similarity among individuals (Gillet et al., Citation2018; Howard & Hoffman, Citation2017). However, the variable-level associations did not necessarily exist on the person level due to individual heterogeneity. Therefore, using the person-centered approach to explore the multidimensionality of SC is of great use.

Adopting the person-centered approach

Considering the limitations of the variable-centered approach to the current study, we ultimately utilized the person-centered approach of latent profile analysis (LPA) to test the combination patterns of SC dimensions within individuals. According to combination patterns of dimension indicators, the approach of LPA could distinguish similar group cases (Lubke & Muthén, Citation2007; Zhen & Zhou, Citation2022; Zhen et al., Citation2019; Zhou et al., Citation2020). Within the same group, individuals demonstrated similar SC dimensional characteristics, while between different groups, individuals have different SC dimension combination patterns (Phillips, Citation2019; Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020). Therefore, through adopting the LPA approach, the current study could identify profiles of six SC dimensions in college students to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the multi-dimensionality of SC.

Few studies have examined the multidimensional nature of SC from a person-centered perspective (Phillips, Citation2019; Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020). For example, a previous study identified three profiles: uncompassionate, moderately self-compassionate, and highly self-compassionate (Phillips, Citation2019). Not surprisingly, the results showed that compared with the other two profiles, individuals in the highly self-compassionate group adjusted better. In another study (Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020), researchers distinguished other profiles, such as indifferent, high responding, and below average profiles, which did not reflect the negative association between opposing dimensions (Castilho et al., Citation2015; Veneziani et al., Citation2017). In the indifferent, high responding, and below average profiles, opposing dimensions were relatively independent and sometimes tended to vary in the same direction (Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020). This has suggested that though high levels of positive self-responding may not necessarily be accompanied by low negative self-responding, both high and low levels of different SC dimensions could coexist simultaneously within the same individual (Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020). This has could indicate the necessity of adopting the person-centered rather than the variable-centered approach to investigate the multidimensionality of SC.

To better clarify the predictive effects of SC profiles on mental health outcomes during the pandemic, this study included retrospective adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as covariates to adjust for their effects. Recent studies (Doom et al., Citation2021; Shreffler et al., Citation2021) have revealed significant associations between retrospective ACEs and mental health during the pandemic. One recent study (Shreffler et al., Citation2021) found that after controlling for demographic characteristics, retrospective ACEs were associated with higher levels of mental health outcomes during the pandemic. Another study (Verlenden et al., Citation2022) showed that even after controlling for pandemic-related stress, the effects of ACEs on depressive symptoms remained significant. There may be a compounding effect of childhood adversity and pandemic-related stress on mental health outcomes, resulting in cumulative vulnerabilities (Wade et al., Citation2021). Overall, recent research has revealed that higher levels of ACEs are still significantly associated with mental health outcomes even when controlling for current stress levels (Békés et al., Citation2023; Doom et al., Citation2021; Verlenden et al., Citation2022). These findings suggest the role of preexisting vulnerabilities such as ACEs in shaping current adaptation (Doom et al., Citation2021; Jernslett et al., Citation2022; Shreffler et al., Citation2021; Wade et al., Citation2021), highlighting the significance of controlling for retrospective ACEs when investigating the influence of SC profiles on mental health outcomes during the pandemic.

Based on the background, this study examined the longitudinal predictive effects of SC profiles on positive (PTG) and negative (depressive and PTSD symptoms) mental health outcomes in Chinese young adults. First, in this study, we expected to identify compassionate and uncompassionate profiles. Second, we hypothesized that young adults in the compassionate group would exhibit the best psychological adjustments among all groups, showing the lowest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms and the highest level of PTG. Conversely, adults in the uncompassionate group would demonstrate the worst mental health outcomes, exhibiting the highest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms, and the lowest level of PTG. Third, while we anticipate discovering additional SC profiles, we have not yet made specific predictions.

Methods

Procedure

The data collection work was divided into two waves. This study’s first wave of data was collected from mid-February to late February 2020. Subjects (college students) participated in the research through an online survey. Questionnaires about socio-demographic information and SC were provided on various online platforms. The project obtained ethical clearance from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the corresponding author’s institution (No.: 2020005). The enrolled students were asked to sign an e-consent form before completing the questionnaire. Three months later, the second wave of data collection was conducted. The same college students were invited to participate and report their depressive and PTSD symptoms and PTG. Furthermore, participants who completed the survey were given a monetary compensation of around 12 RMB (approximately 1.5 USD), which was paid through an online payment platform.

Participants

In the first wave, 1218 students completed the questionnaires, among which 1164 were considered valid data. At the second measurement, 1099 participants were retained in the study, but seven participants were screened for invalid data. The matching of the 2-wave subjects was done by the phone numbers they filled in. The detailed demographic information of the participants is presented in .

Table 1. Demographic information of participants.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Participants were asked to report their age, gender (male or female), having a sibling (s) or not, family structure (intact or non-intact), and residence (urban or rural area). All of these sociodemographic characteristics were controlled in the analysis.

Self-compassion

Each participant was given a 26-item Self-Compassion Scale, which assesses six dimensions of SC: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and overidentification. Their responses are identified on a five-point scale from “Almost never” to “Almost always”. The score of each dimension was summed up and then averaged; the results showed that the higher scores indicate a higher level of the specific SC dimension. The questionnaire previously showed good reliability and validity in Chinese populations (A. Liu et al., Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). The Cronbach α coefficient of the scale in the present study was 0.89.

Depressive symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to assess depressive symptoms (Levis et al., Citation2019); and its Chinese version has been validated and widely used among Chinese adolescents (Li et al., Citation2020). There are altogether nine items, and each item is scored from 0 to 3 (0 = “not at all” to 3 = “Nearly every day”) with total scores ranging from 0 to 27. The more severe the depressive symptoms are, the higher scores will be made. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.88.

Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

To evaluate PTSD symptoms (Lang & Stein, Citation2005; Lang et al., Citation2012), we used the abbreviated PTSD Checklist Civilian Version (PCL-C). The six-item version selects items 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, and 15 from the original PTSD Checklist-Civilian version and has five correspond options (from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). Participants were asked to report their experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. The total score ranges from 6 to 30, and a high score indicates a high level of PTSD symptoms. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the PCL-C have been tested in diverse samples of Chinese (Wang et al., Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2007), including adolescents experiencing an earthquake (Z. Liu et al., Citation2010; Ran et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2012), adults who lost their parents (He et al., Citation2014), female victims of sexual assault (Sui et al., Citation2014). According to previous studies (Chi et al., Citation2021; Ni et al., Citation2020), the score higher than 14 is an indication of clinical PTSD symptoms. Hence, we also classified a score of at least 14 as an indication of probable clinical PTSD symptoms. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.83.

Posttraumatic growth

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) was used to evaluate the positive changes after major stress events (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996), and in previous research, its Chinese version has proved to have good validity (Wang et al., Citation2011; Zhou et al., Citation2014). The PTGI consists of 21 items, and participants were asked on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not experience this change) to 5 (very great degree). The total score was averaged in this study, and a higher level of PTG is reflected in a higher score of the indicator. Cronbach’s α for the PTGI in this study is 0.96.

Adverse childhood experiences

Adverse childhood experiences were measured with 29 items, which assessed physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual assault, emotional neglect, physical neglect, parental separation or divorce, domestic violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness, and an incarcerated household member (Finkelhor et al., Citation2015; Murphy et al., Citation2014). These forms of adversity that occurred before the age of 18 years were scored as either absent (“no”) or present ("yes"), corresponding to a score of 0 or 1, respectively. These scores were then accumulated to obtain the total ACEs score. A high total score indicates that an individual has experienced more forms of adverse experiences. The ACE scale has been revised and validated in Chinese populations (Guo et al., Citation2021). In the current study, the total score of ACEs was included as a controlling variable in the LPA analysis.

Data analysis

Data analyses were conducted in three steps. First, we utilized descriptive statistics and correlation analyses in SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Second, the standardized scores of six SC dimensions were used as indicators to conduct the LPA in MPlus Version 8.3. In the LPA analysis, ACEs scores and sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, have siblings or not, family structure, and residence) were included as controlling variables. Third, to examine the effect of SC profiles on mental health outcomes (specifically, differences in the effects of SC subgroups on depressive symptoms), we adopted the three-step method (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014; Vermunt, Citation2010) with equal variances in the regression mixture model (RMM) for predicting continuous distal variables.

Results

Descriptive analysis

shows the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among SC dimensions and mental health outcomes in Chinese young adults. Self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness were negatively related to depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, positively related to PTG. Self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification were positively related to depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, negatively related to PTG. Retrospective ACEs were significantly related to SC dimensions, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and PTG. Hence, we controlled retrospective ACEs in the analysis.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations for the main study variables.

Latent profile modeling dimensions of self-compassion

After controlling scores of ACEs, the four-class model was chosen as the best option due to its high model fit indices and clear, interpretable profiles. It showed a decrease in BIC values but eventually reached a stable point. Although the five-class model also had a significant VLMR LRT p value, it included a small class with fewer than 20 individuals, which resembled one class in the four-class model. Given the high VLMR LRT p value, the four-class model was considered the best-fitting model.

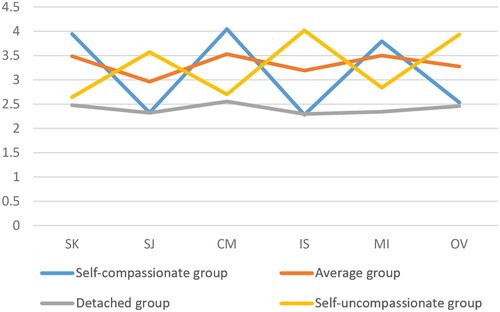

The largest group in the four-class model, labeled “Average group”, had standardized scores near the average for all SC dimensions (n = 614, 55.9% of the sample). In the second largest group, positive SC dimension levels were higher than average, while negative SC dimension levels were lower (labeled “Self-compassionate group”; n = 294, 26.7% of the sample). However, in the third group, positive SC dimension levels were lower, while negative SC dimension levels were higher than the average (labeled “Self-uncompassionate group”; n = 135, 12.3% of the sample). In the last group, all SC dimension levels present the lowest in the whole samples (labeled “Detached group”; n = 56, 5.1% of the sample) ().

Table 3. Model fit indices for standardized results.

Comparing mental health outcomes after controlling ACEs

In the RMM analysis in , young adults in the self-compassionate group scored lowest in the four subgroups on depressive and PTSD symptoms (p < .001) while significantly higher on PTG (p < .001) across the four groups. In the self-uncompassionate group, young adults scored higher on depressive and PTSD symptoms (p < .05) than those in the average and detached group, while they scored lower on PTG (p < .05) than adults in the other two groups. Though on the level of depressive and PTSD symptoms, no significant differences were presented between the average group and the detached group (p > .05), young adults in the average group scored comparatively higher than those in the detached group on PTG (p < .01) ().

Figure 1. The mean scores of self-compassion dimensions across different profiles. SK: self-kindness; SJ: self-judgment; CM: common humanity; IS: isolation; MI: mindfulness; OV: overidentification.

Table 4. Mean scores and differences of mental health outcomes across self-compassion profiles.

Discussion

In a nutshell, this study has identified four distinct SC profiles: self-compassionate, self-uncompassionate, detached, and average. Overall, young adults in the self-compassionate group demonstrated better psychological adjustments than adults in all other groups. They exhibited the highest level of PTG and the lowest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms. In contrast, young adults in the self-uncompassionate group displayed the worst psychological adaptations across the groups. They showed the lowest level of PTG and the highest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms. Young adults in the average groups did not differ significantly from adults in the detached group in terms of the level of depressive and PTSD symptoms. However, adults in the average group experienced more PTG than adults in the detached group.

In the self-compassionate and self-uncompassionate group, the level of positive and negative dimensions tended to vary in opposing directions. The statistics showed the negative dimensions fell as the positive dimensions lifted, and vice versa. In these two groups, young adults performed opposite average scores on the bipolar dimensions. This has supported the view that SC could be considered as “an interactive and synergistic system” (Neff, Citation2016; Neff et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Additionally, the study found that SC displayed a relatively balanced pattern in these two groups, which is similar to prior studies that opposite dimensions on each component (e.g. self-judgement and self-kindness) are often conversely related to each other (Castilho et al., Citation2015; Veneziani et al., Citation2017).

Nevertheless, a relatively different pattern emerged in the average and detached groups. In these two groups, instead of varying in opposing directions, the positive and negative SC dimensions tended to maintain similar levels (Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020). Both of the average and detached groups demonstrated almost the same levels of all dimensions. This has indicated that it is necessary and significant to simultaneously consider different dimensions and explore its influence on mental health. Moreover, the results have suggested the shortcomings of the reverse coding approach to formulating a composite SC score (Ullrich-French & Cox, Citation2020), given the relatively independent associations between positive and negative dimensions in these two groups.

In terms of longitudinal influence on mental health outcomes, young adults in the self-compassionate group adjusted best (the highest level of PTG and the lowest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms) across all the groups. Young adults with higher levels of self-kindness could better understand and care more about themselves, and treat their inadequacies in a nonjudgmental manner (Shin & Lim, Citation2019). Higher levels of self-kindness could help alleviate negative emotions, facilitate their understanding of the traumatic experiences during the pandemic and finally lead to more PTG (Shin & Lim, Citation2019). However, on the contrary, if the suffering experience related to the pandemic cannot be seen as a part of all human experiences, then the sense of isolation rose and they might not obtain positive psychological growth from such common experiences (Wong & Yeung, Citation2017). Moreover, researchers (Neff et al., Citation2017, Citation2019) added that young adults with more mindfulness could become aware of present thoughts and feelings in a balanced manner, would not overidentify or downplay their own suffering experience, which could promote their acceptance and understanding of the pandemic, finally resulting in less PTSD symptoms and more PTG (Wong & Yeung, Citation2017).

Moreover, young adults in the detached group also demonstrated more PTG compared to those in the self-uncompassionate group. We noted that the positive dimensions in the self-uncompassionate group were slightly higher than those in the detached group. Young adults in the detached group have demonstrated the lowest levels of all SC dimensions in the whole samples, but they still achieved more PTG compared with those in the self-uncompassionate group. The dimension pattern in the self-uncompassionate group may help explain this phenomenon (Chi et al., Citation2022). Young adults in this group possessed a pattern with a much lower positive responses relative to their negative responses, even though they tended to sometimes self-respond more positively than young adults in the detached group. But taking different magnitudes between positive and negative dimensions into consideration, it is both the absolute levels of positive dimensions (A. Liu et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b) and the relative balance between opposing dimensions that ultimately determined PTG (Chi et al., Citation2022). In order to promote PTG in young adults, efforts should be made in intervention program to reduce negative self-responding (Wong & Yeung, Citation2017), and simultaneously improve positive self-responding (A. Liu et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Wong & Yeung, Citation2017), and more importantly, to greatly promote positive responses rather than negative responses (Chi et al., Citation2022). Therefore, our findings emphasized the importance of investigating specific functions regarding the relative balance between opposing responses within each SC components for individuals.

Limitation and future directions

This study has limitations. First, this study was based on a sample of general populations. Therefore, it may not be appropriate to generalize the results into other samples. Future research could investigate whether different SC profiles would exist in clinical populations such as depressed patients and how the SC profiles influence their mental health outcomes. Second, the current study only explored the longitudinal outcomes of SC profiles. It is worthwhile to explore the antecedents of SC profiles such as attachment to provide more intervention suggestions. Third, this study only utilized the person-centered approach to investigate the multidimensional structure of SC. Future research could adopt multiple approaches simultaneously to examine whether this would result in different results to deepen the understanding of SC.

Implications

This study revealed distinct profiles of multidimensional SC among Chinese young adults. Moreover, this study revealed that different SC dimensions patterns were differentially associated with mental health outcomes longitudinally. This indicated the significance of adopting six-dimension scores to test its associations with mental health. Previous researches have usually adopted the total score of SC, without mentioning the relative balance. This may be misleading when linking SC to positive mental health outcomes. Our findings suggested that intervention programs should pay attention to increase positive SC aspects and promote more positive SC over negative SC dimensions to facilitate young adults’ psychological adaptation.

Conclusion

This study identified distinct SC profiles among young adults, categorized into self-compassionate, self-uncompassionate, average, and detached groups. Overall, young adults in the self-compassionate group exhibited superior adjustments compared to adults in other groups, showing lower depressive and PTSD symptoms and higher PTG during the pandemic. In contrast, young adults in the self-uncompassionate group displayed the lowest PTG levels and the highest levels of depressive and PTSD symptoms across all groups. Young adults in the average groups did not significantly differ from adults in the detached group in terms of depressive and PTSD symptoms, but those in the average group reported higher PTG than adults in the detached group.

The study emphasizes the importance of considering individual SC profiles when examining their predictive effects on mental health outcomes. Practically, our findings suggest that interventions targeting SC could enhance mental health outcomes for young adults. By recognizing and addressing individual differences in SC profiles, practitioners can tailor interventions to meet the specific needs of each group. For instance, to promote positive outcomes such as PTG, intervention programs could incorporate more methods to facilitate positive SC skills, encouraging individuals to treat themselves kindly and enhancing their mindfulness. However, to alleviate negative psychological symptoms, intervention programs should focus on maintaining the relative balance between different SC dimensions. It is essential to highlight that the composite SC score may not accurately capture the relative balance of different SC dimensions. Our results indicate that achieving this balance may be more crucial than the absolute SC level to mitigate depressive and PTSD symptoms, especially when the levels of all six SC dimensions were below average.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were conducted by Liuyue Huang and Ying Zhang. Data analysis was performed by Liuyue Huang, Yizhen Ren, and Di Zeng. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yizhen Ren and Xinli Chi. Ying Zhang and Xinli Chi edited and reviewed the manuscript. Xinli Chi is responsible for the whole project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

The project obtained ethical clearance from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University (Code number: PN-2021-0069).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21, 329–341.

- Békés, V., Starrs, C. J., & Perry, J. C. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic as traumatic stressor: Distress in older adults is predicted by childhood trauma and mitigated by defensive functioning. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 15(3), 449–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001253

- Berryhill, M. B., & Smith, J. (2021). College student chaotically-disengaged family functioning, depression, and anxiety: The indirect effects of positive family communication and self-compassion. Marriage & Family Review, 57(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1740373

- Bluth, K., & Blanton, P. W. (2015). The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936967

- Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Evaluating the multifactor structure of the long and short versions of the Self-Compassion Scale in a clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22187

- Chi, X., Becker, B., Yu, Q., Willeit, P., Jiao, C., Huang, L., Hossain, M. M., Grabovac, I., Yeung, A., Lin, J., Veronese, N., Wang, J., Zhou, X., Doig, S. R., Liu, X., Carvalho, A. F., Yang, L., Xiao, T., Zou, L., … Solmi, M. (2020). Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of mental health outcomes among Chinese college students during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 803. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00803

- Chi, X., Huang, L., Hall, D. L., Li, R., Liang, K., Hossain, M. M., & Guo, T. (2021). Posttraumatic stress symptoms among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 759379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.759379

- Chi, X., Huang, L., Zhang, J., Wang, E., & Ren, Y. (2022). Latent profiles of multi-dimensionality of self-compassion predict youth psychological adjustment outcomes during the COVID-19: A longitudinal mixture regression analysis. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03378-3

- Doom, J. R., Seok, D., Narayan, A. J., & Fox, K. R. (2021). Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences predict mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adversity and Resilience Science, 2(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-021-00038-6

- Elhami Athar, M. (2023). Understanding the relationship between psychopathic traits and client variables: Variable-centered and person-centered analytic approaches. Current Psychology, 43(14), 12477–12494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05322-5

- Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2015). A revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011

- Forte, G., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R., & Casagrande, M. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population: Validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114151

- Gillet, N., Morin, A. J. S., Sandrin, E., & Houle, S. A. (2018). Investigating the combined effects of workaholism and work engagement: A substantive-methodological synergy of variable-centered and person-centered methodologies. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 109, 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.09.006

- Guo, T., Huang, L., Hall, D. L., Jiao, C., Chen, S. T., Yu, Q., Yeung, A., Chi, X., & Zou, L. (2021). The relationship between childhood adversities and complex posttraumatic stress symptoms: A multiple mediation model. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1936921. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1936921

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, M. E., Fanjul Rodríguez, L. F., Díaz Megolla, A., Oyanadel, C., & Peñate Castro, W. (2022). Analysis of the predictive role of self-compassion on emotional distress during COVID-19 lockdown. Social Sciences, 11(4), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040151

- He, L., Tang, S., Yu, W., Xu, W., Xie, Q., & Wang, J. (2014). The prevalence, comorbidity and risks of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Chinese adults. Psychiatry Research, 219(2), 347–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.022

- Howard, M. C., & Hoffman, M. E. (2017). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021

- Huang, L., Chi, P., Wang, E., Bu, H., & Chi, X. (2023). Trajectories of complex posttraumatic stress symptoms among Chinese college students with childhood adversities: The role of self-compassion. Child Abuse & Neglect, 150, 106138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106138

- Jernslett, M., Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X., Lioupi, C., Syros, I., Kapatais, A., Karamanoli, V., Evgeniou, E., Messas, K., Palaiokosta, T., Papathanasiou, E., & Lotzin, A. (2022). Disentangling the associations between past childhood adversity and psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of specific pandemic stressors and coping strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105673

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Murphy, J., McBride, O., Ben-Ezra, M., Bentall, R. P., Vallières, F., & Hyland, P. (2020). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and associated comorbidity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland: A population-based study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(4), 365–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22565

- Krieger, T., Berger, T., & Holtforth, M. G (2016). The relationship of self-compassion and depression: Cross-lagged panel analyses in depressed patients after outpatient therapy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.032

- Lang, A. J., & Stein, M. B. (2005). An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(5), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005

- Lang, A. J., Wilkins, K., Roy-Byrne, P. P., Golinelli, D., Chavira, D., Sherbourne, C., Rose, R. D., Bystritsky, A., Sullivan, G., Craske, M. G., & Stein, M. B. (2012). Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(4), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.003

- Levis, B., Benedetti, A., & Thombs, B. D., DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. (2019). Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ, 365, l1476. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1476

- Li, A., Wang, S., Cai, M., Sun, R., & Liu, X. (2021). Self-compassion and life-satisfaction among Chinese self-quarantined residents during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model of positive coping and gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, 110457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110457

- Li, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Du, S., & Lingxia, Z. (2020). Psychological survey of COVID-19 in the general public. Infection International, 9(2), 308–310.

- Li, Y., Zhao, J., Ma, Z., McReynolds, L. S., Lin, D., Chen, Z., Wang, T., Wang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Fan, F., & Liu, X. (2021). Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A 2-wave longitudinal survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.109

- Liang, K., Huang, L., Qu, D., Bu, H., & Chi, X. (2022). Self-compassion predicted joint trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: A five-wave longitudinal study on Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 319, 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.078

- Liu, A., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2020). Understanding the relation between self-compassion and suicide risk among adolescents in a post-disaster context: Mediating roles of gratitude and posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01541

- Liu, A., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2021a). The mediating role of rumination in the relation between self-compassion, posttraumatic stress disorder, and posttraumatic growth among adolescents after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3846–3859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01643-5

- Liu, A., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2021b). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth mediate the relations between social support, prosocial behavior, and antisocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1864949. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1864949

- Liu, A., Xu, B., Liu, M., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2023). The reciprocal relations among self-compassion, and depression among adolescents after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(8), 1786–1798. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23501

- Liu, C. H., Zhang, E., Wong, G. T. F., Hyun, S., & Hahm, H. C. (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172

- Liu, S., Zou, S., Zhang, D., Wang, X., & Wu, X. (2022). Problematic Internet use and academic engagement during the COVID-19 lockdown: The indirect effects of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in early, middle, and late adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 309, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.043

- Liu, Z., Yang, Y., Ye, Y., Zeng, Z., Xiang, Y., & Yuan, P. (2010). One-year follow-up study of post-traumatic stress disorder among adolescents following the Wen-Chuan earthquake in China. BioScience Trends, 4(3), 96–102.

- Lubke, G., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Performance of factor mixture models as a function of model size, covariate effects, and class-specific parameters. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1401_2

- Murata, S., Rezeppa, T., Thoma, B., Marengo, L., Krancevich, K., Chiyka, E., Hayes, B., Goodfriend, E., Deal, M., Zhong, Y., Brummit, B., Coury, T., Riston, S., Brent, D. A., & Melhem, N. M. (2021). The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depression and Anxiety, 38(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23120

- Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(2), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2005

- Murphy, A., Steele, M., Dube, S. R., Bate, J., Bonuck, K., Meissner, P., Goldman, H., & Steele, H. (2014). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire and Adult Attachment Interview (AAI): Implications for parent child relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(2), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004

- Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863

- Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390209035

- Neff, K. D. (2016). The Self-Compassion Scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3

- Neff, K. D., Long, P., Knox, M., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., Costigan, A., Williamson, Z., Rohleder, N., Tóth-Király, I., & Breines, J. (2018). The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self and Identity, 17(6), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1436587

- Neff, K. D., Tóth-Király, I., Yarnell, L. M., Arimitsu, K., Castilho, P., Ghorbani, N., Guo, H. X., Jameson, H. K., Hupfeld, J., Hutz, C. S., Kotsou, I., Kyeong, W. L., Marin, J. M., Sirois, F. M., Souza, L. K., Svendsen, L. J., Wilkinson, R. B., & Mantzios, M. (2019). Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in 20 diverse samples: Support for use of a total score and six subscale scores. Psychological Assessment, 31(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000629

- Neff, K. D., Whittaker, T. A., & Karl, A. (2017). Examining the factor structure of the self-compassion scale in four distinct populations: Is the use of a total scale score justified? Journal of Personality Assessment, 99(6), 596–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1269334

- Ni, M. Y., Yao, X. I., Leung, K. S. M., Yau, C., Leung, C. M. C., Lun, P., Flores, F. P., Chang, W. C., Cowling, B. J., & Leung, G. M. (2020). Depression and post-traumatic stress during major social unrest in Hong Kong: A 10-year prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 395(10220), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33160-5

- North, C. S., Suris, A. M., & Pollio, D. E. (2021). A nosological exploration of PTSD and trauma in disaster mental health and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 11(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11010007

- Ochnik, D., Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., Jakubiak, M., Wierzbik-Strońska, M., Schütz, A., Held, M. J., Arzenšek, A., Pavlova, I., Korchagina, E. V., Aslan, I., & Çınar, O. (2021). Exposure to COVID-19 during the first and the second wave of the pandemic and coronavirus-related PTSD risk among university students from six countries—A repeated cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(23), 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235564

- Phillips, W. J. (2019). Self-compassion mindsets: The components of the Self-Compassion Scale operate as a balanced system within individuals. Current Psychology, 40(10), 5040–5053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00452-1

- Rahmati Kankat, L., Farhadi, M., Valikhani, A., Hariri, P., Long, P., & Moustafa, A. A. (2020). Examining the relationship between personality disorder traits and inhibitory/initiatory self-control and dimensions of self-compassion. Psychological Studies, 65(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00582-8

- Ran, M. S., Zhang, Z., Fan, M., Li, R. H., Li, Y. H., Ou, G. J., Jiang, Z., Tong, Y. Z., & Fang, D. Z. (2015). Risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 13, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.016

- Rudenstine, S., McNeal, K., Schulder, T., Ettman, C. K., Hernandez, M., Gvozdieva, K., & Galea, S. (2021). Depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in an urban, low-income public university sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22600

- Shek, D. T. L., Zhao, L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Xiao, C. (2021). The impact of positive youth development attributes on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese adolescents under COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(4), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.011

- Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., & Karatzias, T. (2020). Is posttraumatic stress disorder meaningful in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? A response to Van Overmeire’s Commentary on Karatzias et al. (2020). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 866–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22592

- Shin, N. Y., & Lim, Y. J. (2019). Contribution of self-compassion to positive mental health among Korean university students. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International de Psychologie, 54(6), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12527

- Shreffler, K. M., Joachims, C. N., Tiemeyer, S., Simmons, W. K., Teague, T. K., & Hays-Grudo, J. (2021). Childhood adversity and perceived distress from the COVID-19 pandemic. Adversity and Resilience Science, 2(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-021-00030-0

- Sui, S. G., King, M. E., Li, L. S., Chen, L. Y., Zhang, Y., & Li, L. J. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder among female victims of sexual assault in China: Prevalence and psychosocial factors. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 6(4), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12155

- Sun, X., Chan, D. W., & Chan, L-K (2016). Self-compassion and psychological well-being among adolescents in Hong Kong: Exploring gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.011

- Tang, W., Hu, T., Hu, B., Jin, C., Wang, G., Xie, C., Chen, S., & Xu, J. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Target article: "Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence". Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G., & Cann, A. (2007). Evaluating resource gain: Understanding and misunderstanding posttraumatic growth. Applied Psychology, 56(3), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00299.x

- Tomaszek, K., & Muchacka-Cymerman, A. (2020). Thinking about my existence during COVID-19, I feel anxiety and awe—The mediating role of existential anxiety and life satisfaction on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and post-traumatic growth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197062

- Ullrich-French, S., & Cox, A. E. (2020). The use of latent profiles to explore the multi-dimensionality of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 11(6), 1483–1499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01365-y

- van Aar, J., Leijten, P., Orobio de Castro, B., Weeland, J., Matthys, W., Chhangur, R., & Overbeek, G. (2019). Families who benefit and families who do not: integrating person- and variable-centered analyses of parenting intervention responses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(10), 993–1003.e1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.004

- Veneziani, C. A., Fuochi, G., & Voci, A. (2017). Self-compassion as a healthy attitude toward the self: Factorial and construct validity in an Italian sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.028

- Verlenden, J., Kaczkowski, W., Li, J., Hertz, M., Anderson, K. N., Bacon, S., & Dittus, P. (2022). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and pandemic-related stress and the impact on adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00502-0

- Vermunt, J. K. (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. https://doi.org/10.2307/25792024

- Vindegaard, N., & Benros, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048

- Wade, M., Prime, H., Johnson, D., May, S. S., Jenkins, J. M., & Browne, D. T. (2021). The disparate impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of female and male caregivers. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 275(7), 113801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113801

- Wang, J., Chen, Y., Wang, Y. B., & Liu, X. H. (2011). Revision of the posttraumatic growth inventory and testing its reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Nursing Science, 26, 26–28.

- Wang, R., Su, J., Bi, X., Wei, Y., & Mo, L. (2012). Application of the Chinese posttraumatic stress disorder checklist to adolescent earthquake survivors in China. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(3), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.3.415

- Wang, X., Liu, S., Wu, X., Ren, Y., & Zou, S. (2023). Work–family conflict, educational involvement, and adolescent academic engagement during COVID-19: An investigation of developmental differences. Family Relations, 72(4), 1491–1510. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12852

- Wong, C. C. Y., & Yeung, N. C. Y. (2017). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth: Cognitive processes as mediators. Mindfulness, 8(4), 1078–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0683-4

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Yang, X., Yang, H., Liu, Q., & Yang, L. (2007). The research on the reliability and validity of PCL-C and influence factors. China Journal of Health Psychology, 15(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-1252.2007.01.036

- Zhen, R., & Zhou, X. (2022). Latent patterns of posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, and posttraumatic growth among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(1), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22720

- Zhen, R., Zhou, X., & Wu, X. (2019). Patterns of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among adolescents following an earthquake: A latent profile analysis. Child Indicators Research, 12(6), 2173–2187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09634-6

- Zhou, X., Wu, X., An, Y., & Chen, J. (2014). The roles of rumination and social support in the associations between core belief challenge and post-traumatic growth among adolescent survivors after the Wenchuan earthquake. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(10), 1509–1520. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.01509

- Zhou, Y., Liang, Y., Tong, H., & Liu, Z. (2020). Patterns of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among women after an earthquake: A latent profile analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 101834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.10.014