Abstract

Purpose: Psychological adjustment has a major impact on chronic disease health outcomes. However, the classification of psychological adjustment is unclear in the current version of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). We aim (i) to characterize the process of psychological adjustment to chronic disease, and (ii) to analyze how various categories of the psychological adjustment process could be incorporated into the ICF.

Method: We provide a summary of models of psychological adjustment to chronic disease. We also evaluate various options for incorporating categories of psychological adjustment into the ICF.

Results: Acute and ongoing illness stressors; emotional, cognitive and behavioral responses; personal background; and social and environmental background are major categories in the adjustment process. These categories could, in principle, be integrated with various components of the ICF. Any future revision of the ICF should explicitly incorporate psychological adjustment and its (sub)categories.

Conclusion: The ICF could incorporate categories of psychological adjustment to chronic disease, although several adaptations and clarifications will be required.

In the context of an ageing society and large numbers of people living with chronic diseases, it is essential to understand psychological adjustment to chronic disease.

However, the classification of psychological adjustment to chronic disease is unclear in the current version of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

We demonstrate that the ICF could incorporate categories of psychological adjustment to chronic disease, although several adaptations and clarifications would first be required.

We suggest that these adaptations and clarifications should be considered in any future revision of the ICF.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Chronic disease induces a wide range of psychological responses, examples of which include uncertainty about the future,[Citation1] anxiety and depressive disorders,[Citation2] and avoidance of physical activity.[Citation3] That psychological responses can have a major impact on health [Citation4] is illustrated by the role of motivational factors in predicting exercise adherence,[Citation5] whereas low adherence to exercise results in fatigue and poor functional status.[Citation6]

We use the term “psychological adjustment” to refer to psychological processes in response to chronic disease and associated treatment. Psychological adjustment refers to processes rather than outcomes: psychological responses to chronic disease can be beneficial, contributing to good health, or they can be detrimental, leading to poor health.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation7] is increasingly accepted as the conceptual model guiding rehabilitation strategies.[Citation8,Citation9] During development of the present version of the ICF little attention was given to the conceptualization of psychological adjustment, i.e., psychological processes in response to disease. We now contend that there is a need to clarify the conceptualization of psychological adjustment in the ICF. The further development of the ICF and the development of rehabilitation strategies using the ICF may benefit from explicitly addressing psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Therefore, we aim (i) to characterize the process of psychological adjustment to chronic disease, and (ii) to analyze how various categories of the psychological adjustment process could be incorporated into the ICF.

Psychological adjustment to chronic disease

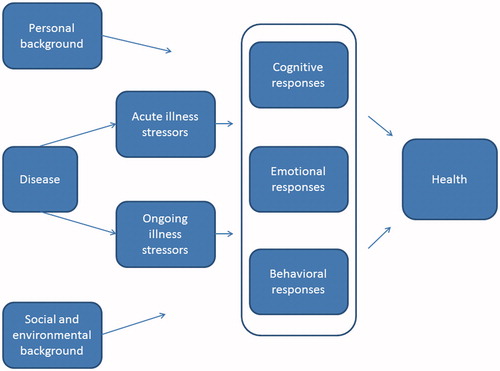

Various psychological models have been developed of how people respond to chronic disease. These include the stress-coping model,[Citation10] the illness representation model,[Citation11] the adaptive tasks and coping model,[Citation12] and the adjustment model.[Citation13] Our schematic summary of these models is illustrated in . Disease induces acute illness stressors (e.g. becoming aware of a disease diagnosis; undergoing burdensome treatment; experiencing a relapse) and ongoing illness stressors (e.g., uncertainty about the future, threats to social relationships). Cognitive and behavioral responses are key elements in the adjustment process, in line with the original stress-coping model,[Citation10] the adaptive tasks and coping model,[Citation12] and the adjustment model.[Citation13] Acute and ongoing illness stressors induce cognitive and behavioral responses that influence health outcomes. An example of a cognitive response leading to good health is self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to perform activities), while wishful thinking is believed to lead to poor health. Engaging in good health behavior is a behavioral response that may lead to good health, whereas avoiding physical activity is assumed to result in poor health.

The emotional response to disease was introduced as a separate pathway by Leventhal.[Citation11] The illness representation model [Citation11] conceptualizes an emotional response and coping with an emotional response as a separate pathway, in parallel with cognitive and behavioral responses. This differs from the stress-coping model,[Citation10] which focuses on cognitive and behavioral responses, and from the adjustment model,[Citation13] which hypothesizes that emotional responses precede cognitive and behavioral responses. Thus, the various models differ in their conceptualization of the temporal relationship between cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses. In line with modern emotion theory,[Citation14] we conceptualize cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses as parallel systems that are loosely coupled (see ). We do not hypothesize a specific temporal sequence; instead, we conceptualize all three responses as parallel and interacting systems.

Personal background (e.g., personality, life goals) and social and environmental background (e.g., socio-economic status, neighborhood) influence adjustment to chronic disease.[Citation10,Citation11,Citation13,Citation15,Citation16] These background factors influence the experience of acute and ongoing stressors, as well as the cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses to these stressors.

In summary, and as illustrated in , disease leads to acute and ongoing illness stressors that induce loosely coupled cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses. These responses then determine health, with personal background and social and environmental background moderating the adjustment process. The cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses are hypothesized to interact. The other relationships in are represented as unidirectional relationships. We are aware of more complex, bidirectional pathways; however, we have not incorporated these more complex pathways in , for reasons of clarity. The relationships as represented in describe the main pathways in the process of psychological adjustment to chronic disease.

Health

Conceptualization of health as the outcome of the adjustment process (see ) can be achieved using either the ICF components of health or the domains of health-related quality of life. Due to the more detailed classification provided by the ICF, we would argue that the ICF components of health are to be preferred.

When conceptualizing outcomes, psychological models of health refer to various domains of health. For example, Moss-Morris [Citation13] refers to physical, psychological and social health, and other psychological models of health refer to more or less similar domains.[Citation16–20] Physical, mental, and social health are the domains most frequently mentioned, while global health or overall quality of life are occasionally added.

An important drawback of these approaches is the rather limited conceptualization of the impact of disease on both the body and the activities of a person. As these approaches rely on patient-reported outcomes, conceptualization of the impact on the body is confined to subjectively experienced symptoms such as pain, fatigue, stiffness, nausea and other symptoms. As an alternative, the ICF provides an elaborate classification of body functions (physiological and psychological functions) and body structures (anatomical parts of the body), which encompasses much more than just subjectively experienced symptoms. Clearly, the elaborate ICF classification of body functions and structures is indispensable for both clinical and scientific purposes in rehabilitation. For example, the detailed classification of functions of the joints and bone cannot be captured by patient-reported outcomes. Likewise, because the goal of the quality-of-life approach is to provide a set of feasible outcome measures, this leads to the impact of disease on various activities being loosely grouped together in domains such as physical function or social function. Again, the much more detailed classification of activities in the ICF is preferable for clinical and scientific purposes in the context of rehabilitation. For example, the detailed classification of activities related to mobility, self-care and interpersonal interactions is to be preferred over global domains such as physical function and social function.

When considering other ICF domains, the difference between ICF components and the domains of health-related quality of life is less clear. Participation restrictions refer to problems an individual may experience in life situations.[Citation7] However, the demarcation between activity limitations and participation restrictions is not fully resolved.[Citation21] Psychological models use “social aspects of health” or “social functioning” to refer to these aspects of health-related functioning. The ICF category “environmental factors” refers to the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives.[Citation7] This category is very similar to the category “social and environmental background” in psychological models. The ICF defines personal factors as “the particular background of an individual’s life and living, and comprise features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states”[Citation7] (p. 17). Although no taxonomy and classification system is available,[Citation7] ICF personal factors seem to encompass the personal background factors in the psychological models.

In summary, in conceptualizing health as the outcome of the psychological adjustment process in rehabilitation, the more detailed classification of components leads us to prefer the ICF components of body functions, body structures and activities over the domains of health-related quality of life as used in psychological models. Regarding the other ICF components, more or less equivalent domains exist in psychological models. Thus, on balance this results in a clear preference for the ICF components when conceptualizing health for both clinical and scientific purposes in rehabilitation.

The ICF and psychological adjustment to chronic disease

It has been suggested that the various categories of psychological adjustment should be classified among the personal factors in the ICF. The current version of the ICF does not provide a taxonomy and classification of personal factors, an omission that seems to be primarily related to concerns about potential misuse of personal factors, for example using personal factors to “blame the victim”.[Citation22] In the absence of an official taxonomy and classification, individual researchers have suggested various classifications of personal factors.[Citation23] Recently, Müller and Geyh [Citation24] reviewed several classifications of personal factors and came up with 12 broad content areas: biological/physiological factors, personality, other health conditions, cognitive psychological factors, emotional factors, motives/motivation, coping, behavioral and lifestyle factors, social relationships, satisfaction, socio-demographic factors and experiences and biography. These content areas are reminiscent of the categories of the psychological model of adjustment to chronic disease (see ). This applies in particular to personality, cognitive psychological factors, emotional factors, motives/motivation, coping, and behavioral and lifestyle factors. This overlap suggests that the categories of the psychological model of adjustment to chronic disease could be classified within the ICF component “personal factors”.

However, Müller and Geyh [Citation24] have pointed out that categorizations by individual researchers do not fully adhere to important principles of classification development, with overlap between the content areas and other components of the ICF as one of the main problems. This applies, for example, to “coping skills” which could also relate to the ICF category “handling stress and other psychological demands” (in the ICF component activity). On the other hand, “handling stress and other psychological demands” is defined as: “Carrying out simple or complex and coordinated actions to manage and control the psychological demands required to carry out tasks demanding significant responsibilities and involving stress, distraction, or crises, such as driving a vehicle during heavy traffic or taking care of many children”.[Citation7] This definition refers primarily to cognitive and neuropsychological aspects of handling stressors; furthermore, it fails to mention disease as a potential stressor. Thus, in our opinion, it is unclear whether or not this definition is meant to include coping with chronic disease. We would argue that disease should be explicitly cited in the ICF as a potential stressor. Similarly, cognitive and behavioral responses to disease should also be explicitly mentioned.

Overlap is also an issue with the content area “emotional factors”. Müller and Geyh [Citation24] point out that this could relate to the ICF category ‘emotional functions’ (in the ICF component body function). Emotional functions have been defined as “specific mental functions related to the feeling and affective components of the processes of the mind”.[Citation7] This could include emotions in response to chronic disease, although this is not specifically indicated. Therefore, we would argue that emotional responses to chronic disease need to be explicitly mentioned in the ICF.

Proposals

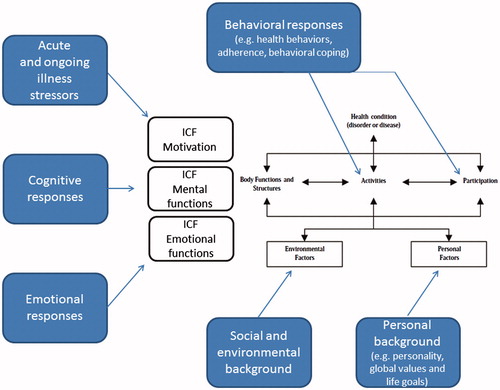

We would like to offer the following proposals regarding incorporation of psychological adjustment to chronic disease into the ICF. In so doing, we draw upon the model of psychological adjustment to chronic disease presented above (see ). We have carefully evaluated whether the categories of this model could be incorporated into the ICF, and if so, whether specific adaptations or clarifications would seem desirable. These proposals are depicted in .

Figure 2. Suggestions on how to incorporate categories of psychological adjustment to chronic disease into the ICF.

First, in any future revision it could be explicitly stated that the ICF covers psychological adjustment, i.e., psychological processes in response to chronic disease. Disease could be mentioned as a potential stressor and the various categories of the psychological adjustment process should be incorporated into the ICF.

Second, we propose that “acute illness stressors” and “ongoing illness stressors” should be incorporated into the ICF category “motivation”. Acute illness stressors (e.g., becoming aware of a diagnosis) and ongoing illness stressors (e.g., a threat to autonomy) are the primary motivating factors of the adjustment process, thus are most appropriately categorized as “motivation”. Motivation is included in the ICF category ‘mental functions’, within the ICF component “body functions”. However, the present ICF version only includes a general description of motivation (“mental functions that produce the incentive to act”). We would therefore suggest that specific items on illness-related motivation should be added, for example the need to manage illness-related stressors such as symptoms, diagnosis and treatment, emotions, threats to self-image, social relationships and uncertainty about the future.[Citation12]

Third, psychological adjustment to chronic disease comprises cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses, responses that need to be explicitly incorporated into the ICF. Currently, the ICF does not explicitly state that it covers these responses. (i) Cognitive responses to chronic disease (e.g., worrying) could be categorized within the ICF category “mental functions”. (ii) Emotional responses (e.g., depressive mood or anger) could be incorporated into the ICF category “emotional functions”. (iii) Behavioral responses fit into the ICF component “activities”. Coping could fit into the subcategory “handling stress and other psychological demands”. However, we suggest that one or more subcategories should be added that explicitly address behavioral responses to chronic disease. Health behaviors such as engaging in physical activity fit into the ICF category “looking after one’s health”, which refers to maintaining a balanced diet and an appropriate level of physical activity and other health behaviors. We propose that other behaviors such as “adherence to medical and self-management regimes” should also be explicitly added. (iv) In cases where behavioral responses occur in a social context, the ICF component “participation” is indicated, possibly in the subcategory “managing complex interpersonal interactions”. However, again we propose that one or more subcategories should be added that explicitly address behavioral responses to chronic disease in a social context, such as seeking social support or participating in patient organizations.

Fourth, personal background in the psychological model (see ) includes personality, global values, life goals, demographics and early life experiences. We suggest that these factors should be categorized in the ICF component “personal factors”. Personality refers to individual differences in characteristic patterns of cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses; general characteristics that are not specifically related to a health condition or health states. Therefore, personality fits in the ICF component “personal factors”. The same applies to global values and life goals: these are motivating factors that influence the adjustment process and outcome.[Citation25] These global values and life goals are features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health state; they therefore belong to the component “personal factors”. The same applies to early life experiences.

Fifth, in the psychological model social and environmental background (e.g., physical environment and medical care) are similar to the ICF component “external factors”. No specific adaptations of this ICF component seem to be required.

Sixth, most of the suggested categories for the psychological adjustment process fall within the ICF components “body functions”, “activities” and “participation”. Only factors such as personality, global values and life goals, which exist independent of health, should be classified in the ICF component “personal factors”. However, it would be helpful if the ICF referred to “body and psychological functions” or “body and mental functions”, rather than to “body functions” only. Although the ICF states that psychological/mental functions are included among body functions, psychological/mental functions could be more explicitly defined in the ICF. Using a different terminology such as ‘body and psychological/mental functions’ would remedy this problem.

Disorders versus psychological processes

In clinical practice, the ICF is used to identify or diagnose disorders: the clinician identifies an impairment in body functions or structures, activity limitations, or problems in participation. The ICF can be used in a similar manner to identify or diagnose disorders resulting from chronic disease. Examples include diagnosis of intrusive thoughts about a disease, depression disorders in reaction to a disease, or severe neglect of health.

However, not all psychological responses are pathological: psychological responses do not necessarily equate to disorders. We defined psychological adjustment as the psychological processes in response to chronic disease; these processes may contribute to good health or to poor health (see above). Worrying about disease may contribute to good health insofar as it contributes to better adherence to medical and self-management regimens. Only if worry becomes maladaptive or “pathological” (e.g., intrusive thoughts interfering with rehabilitation and leading to significant distress and disability) should it be considered a disorder.[Citation14,Citation26] The same reasoning applies to emotional and behavioral responses to disease, responses that can be highly adaptive and may contribute to good health. These responses should be considered a disorder only when responses are maladaptive and interfere with rehabilitation or lead to significant distress and disability.

The ICF can be used in two distinct ways: (i) to describe psychological processes which affect health, and (ii) to identify or diagnose disorders in psychological responses to chronic disease that require treatment. The ICF can thus be used to both describe psychological responses and to identify or diagnose responses as disorders if they interfere with rehabilitation and become disabling.

Discussion and conclusion

In the context of an ageing society and large numbers of people living with chronic diseases, it has been proposed that health should be redefined as “the ability to adapt and to self-manage”.[Citation19] This definition emphasizes human functioning, even in the presence of disease. It also emphasizes the capacity to cope and to maintain and restore health, i.e., it emphasizes psychological adjustment. In the light of these developments, it is essential to clarify how psychological adjustment to chronic disease can be incorporated into the ICF. We identified acute and ongoing illness stressors; cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses; personal background; and social and environmental background as categories in the adjustment process (see ). We also provided suggestions on how to integrate these categories into the ICF (see ). We are under the impression that the ICF can incorporate these categories, although a number of adaptations and clarifications will be required. We strongly urge that these adaptations and clarifications should be considered in any future revision of the ICF.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Kwakkenbos L, Willems LM, van den Hoogen FH, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy targeting fear of progression in an interdisciplinary care program: a case study in systemic sclerosis. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2014;21:297–312.

- Dekker J, Braamse A, van Linde ME, et al. One in three patients with cancer meets the criteria for mental disorders: what does that mean? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2826–2828.

- Holla JF, Sanchez-Ramirez DC, van der Leeden M, et al. The avoidance model in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the evidence. J Behav Med. 2014;37:1226–1241.

- de Ridder D, Geenen R, Kuijer R, et al. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Lancet. 2008;372:246–255.

- Husebo AM, Dyrstad SM, Soreide JA, et al. Predicting exercise adherence in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational and behavioural factors. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:4–21.

- Gerritsen JK, Vincent AJ. Exercise improves quality of life in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:796–803.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Stucki G, Ewert T, Cieza A. Value and application of the ICF in rehabilitation medicine. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:932–938.

- Stucki G, Melvin J. The international classification of functioning, disability and health: a unifying model for the conceptual description of physical and rehabilitation medicine. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:286–292.

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

- Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representation and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1984. p. 219–252.

- Moos RH, Holohan CJ. Adaptive tasks and coping with illness and disability. In: Martz E, Livneh H, editors. Coping with chronic illness and disability. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 107–126.

- Moss-Morris R. Adjusting to chronic illness: time for a unified theory. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18:681–686.

- Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Feldman BL. Handbook of emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010.

- Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Tennen H. Health psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:565–592.

- Ware JE Jr, Standards for validating health measures: definition and content. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:473–480.

- Cella DF. Quality of life: concepts and definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994;9:186–192.

- Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65.

- Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163.

- PROMIS Health Organization. [16 March 2016]. Available from: http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/domainframework.

- Eyssen IC, Steultjens MP, Dekker J, et al. A systematic review of instruments assessing participation: challenges in defining participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:983–997.

- Simeonsson RJ, Lollar D, Bjorck-Akesson E, et al. ICF and ICF-CY lessons learned: Pandora’s box of personal factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:2187–2194.

- Geyh S, Peter C, Muller R, et al. The personal factors of the international classification of functioning, disability and health in the literature – a systematic review and content analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1089–1102.

- Muller R, Geyh S. Lessons learned from different approaches towards classifying personal factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:430–438.

- Littooij E, Leget CJ, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, et al. The importance of “global meaning for people rehabilitating from spinal cord injury”. Spinal Cord. 2016. doi. 10.1038/sc2016.48.

- Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence–a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psychooncology. 1997;6:95–105.