Abstract

Purpose: This article examines the employment situation and perceptions of graduates from three rehabilitation technician (RT) programs in Haiti.

Methods: In this mixed method study, 74 of 93 recent graduates completed a questionnaire, and 20 graduates participated in an in-depth qualitative interview. We analyzed survey results using descriptive statistics. We used a qualitative description approach and analyzed the interviews using constant comparative techniques.

Results: Of the 48 survey respondents who had completed their training more than six months prior to completing the questionnaire, 30 had found work in the rehabilitation sector. Most of these technicians were working in hospitals in urban settings and the patient population they treated most frequently were patients with neurological conditions. Through the interviews, we explored the participants’ motivations for becoming a RT, reflections on the training program, process of finding work, current employment, and plans for the future. An analysis of qualitative and quantitative findings provides insights regarding challenges, including availability of supervision for graduated RTs and the process of seeking remunerated work.

Conclusions: This study highlights the need for stakeholders to further engage with issues related to formal recognition of RT training, expectations for supervision of RTs, concerns for the precariousness of their employment, and uncertainty about their professional futures.

The availability of human resources in the rehabilitation field in Haiti has increased with the implementation of three RT training programs over the past 10 years.

RTs who found work in the rehabilitation sector were more likely to work in a hospital setting, in the province where their training had taken place, to treat a diverse patient clientele, and to be employed by a non-governmental organization.

The study underlines challenges related to the long-term sustainability of RT training programs, as well as the employment of their graduates.

Further discussion and research are needed to identify feasible and effective mechanisms to provide supervision for RTs within the Haitian healthcare system.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Prior to the January 2010 earthquake, rehabilitation services in Haiti were scarce [Citation1–4]. For a population in which one in six households included a person with a disability [Citation5], most of these services were provided through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and religious institutions [Citation1,Citation6]. After the earthquake, the need for rehabilitation became even more evident due to the increased number of Haitians with permanent impairments; an estimated 300,000 Haitians were injured by the earthquake, including between 2000 and 4000 new amputees [Citation7]. As a result, rehabilitation services were extremely overstretched due to an imbalance “between the needs for rehabilitation and the capacity of the country to supply these services from financial and human resource capacity” [Citation8, p.1617].

Since 2010, there have been significant changes in the rehabilitation sector in Haiti. Some Haitian physical therapists (PTs), who had left the country to receive their professional training, returned. As a result, the number of PTs was estimated to have increased from 12 in 2009 to 30 in 2015 [Citation9,Citation10]. As part of the international and national response to the earthquake, many rehabilitation projects were established with the goal of providing assistance to persons with newly acquired injuries and individuals with preexisting disabilities. Since that time, the NGO sector has progressively transitioned from a disaster relief model to development-oriented aid activities [Citation2]. Alongside these changes, concerns have been expressed for the sustainability of rehabilitation programs [Citation11].

An important consideration for the Haitian rehabilitation sector has been the possibility of training rehabilitation providers in Haiti. Due to the absence of university-based rehabilitation education programs in their own country, until very recently Haitians had to travel to the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Brazil, or the USA to complete a bachelor’s or master’s degree in physical or occupational therapy [Citation2,Citation3]. Similar to initiatives in other low and middle-income countries [Citation12–17], local and international NGOs implemented programs in Haiti to train rehabilitation technicians (RTs)1 as a means of addressing the lack of rehabilitation providers. Despite diversity in the duration and curricular content of these mid-level programs, graduates were all trained to work under the supervision of a PT, occupational therapist (OT), physician or, in some circumstances, a nurse [Citation3,Citation12].

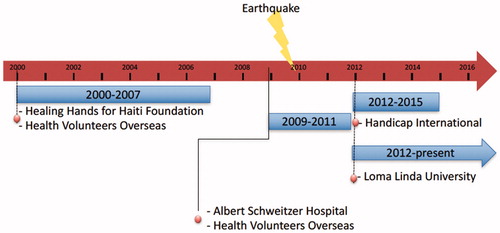

To our knowledge, two RT training programs were implemented prior to the 2010 earthquake. As shown in , the first program was held in Port-au-Prince (West department) between 2001 and 2007 and was organized by the Healing Hands for Haiti Foundation in collaboration with Health Volunteers Overseas [Citation3,Citation17,Citation18]. The second program was organized jointly by Health Volunteers Overseas and the Albert Schweitzer Hospital at Deschapelles (Artibonite department). The program graduated three cohorts of RTs between 2009 and 2011 [Citation18]. The original Health Volunteers Overseas training curriculum of 1500 h, which was approved by the departmental Direction Sanitaire de l’Artibonite of the Ministry of Public and Population Health, was extended to 2500 h in 2014 in order to comply with the Education Ministry’s requirements for a technician-level training program [Citation18]. Following the earthquake, the NGO Handicap International [Citation19] and U.S.-based Loma Linda University [Citation20] both established new RT training programs in Port-au-Prince (West department). These organizations independently developed their training programs and established their curricula. In 2014, Health Volunteers Overseas, Handicap International and Loma Linda University collaboratively developed a standardized competency profile and training plan for RTs that they presented to the Ministry of Public and Population Health with the objective of receiving formal national recognition of the RT competency profile and diploma [Citation21]. At the time of writing this article, this recognition had yet to be accorded.

The first national association of PTs in Haiti, the Société Haitienne de Physiothérapie, was also formed in 2010 [10] and was officially recognized by the Haitian government in 2012. The Haitian rehabilitation sector continues to evolve, with the creation of the first master’s degree program of Physical Therapy at l’Université de la Fondation Dr. Aristide (UNIFA) in 2014 [22]. This changing context is likely to influence the employment opportunities available to rehabilitation providers, including RTs, in the coming years [Citation2].

Alongside the implementation of RT training programs, questions have been raised about opportunities and barriers for the graduates to find employment in Haiti [Citation3]. In a study of RTs trained from 2001 to 2003 in the Healing Hands for Haiti program, Bigelow identified insufficient resources available to support RT training programs, limited opportunities for employment and supervision for RTs upon graduation, and challenges to demonstrate the cost effectiveness of rehabilitation services [Citation3]. Limited information is available about how the rehabilitation sector and rehabilitation training have continued to shift over the past decade, including after the 2010 earthquake. A better understanding of the employment situation and perceptions of graduated RTs can provide important information to inform ongoing and future efforts to build capacity and expand rehabilitation services in Haiti. This mixed method study aims to address this knowledge gap.

Methods

We undertook a convergent mixed method study that included two components: a descriptive cross-sectional survey using questionnaires, and in-depth interviews oriented by a qualitative descriptive [Citation23] approach. We conducted the two components of the data collection between June 2014 and June 2015. We then analyzed the results of each component concurrently [Citation24]. A comparison of these data sources during the analysis process allowed for a richer understanding of the phenomenon of interest than would have been achieved by using a single data source.

Component 1: survey

Survey development

We conducted a survey with recent graduates in order to access descriptive information about their employment situation and professional practice profiles. We developed a French-language questionnaire based on a review of the literature, the research team’s experiences in rehabilitation capacity building projects, and discussion with instructors in an RT training program in Haiti. Two Haitian and two expatriate rehabilitation professionals involved in the training of RTs in Haiti, as well as one of the coauthors who is a Haitian PT (DC), reviewed the provisional version and proposed revisions to increase comprehensibility and relevance for the Haitian context. The survey was administered in 2014 to RTs who had graduated prior to 2014. In 2015, it was administered to two additional cohorts of graduates from training programs that were completed in the intervening year. In 2014, we used a 49-item version of the questionnaire. After analysis of the data, and in consultation with six Haitian rehabilitation professionals, we made additional refinements in 2015. As well as small edits to increase the clarity of several questions, we removed five questions that were judged to be less relevant, resulting in a 44-item questionnaire.

Survey data collection

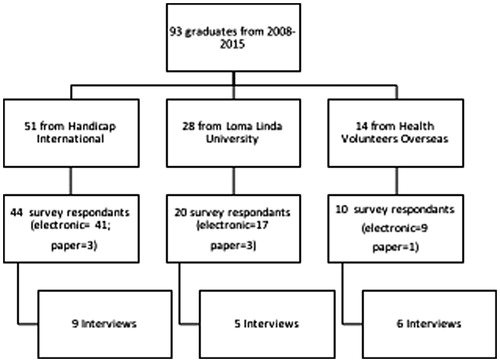

Coordinators of the three training programs provided us with the graduates’ contact information. Recruitment was initiated in June 2014 and May 2015 by sending emails to all 96 graduates from training programs run by Handicap International (22 RT graduates in 2014, 29 in 2015), Loma Linda University (16 graduates in 2014, 12 in 2015), and Health Volunteers Overseas (14 graduates between 2009 and 2011) (see ). We invited graduates to complete an online questionnaire via Internet links to the web-based open-source software LimeSurvey™ version 1.92 + [Citation25] and we sent a reminder email one week later. In addition, we contacted graduates by phone to verify if they had received the email inviting them to participate in the survey. Paper copies of the questionnaire were made available for graduates who were interested in participating in the survey but did not have access to the Internet, or preferred to fill out a paper copy. Seven participants chose to complete the paper version of the questionnaire, and members of the research team manually entered these data into the LimeSurvey™ database.

Of the 96 RT graduates who were invited to complete the questionnaire, 74 accepted. Amongst the 74 survey respondents, 48 had completed their studies at least six months prior to filling out the questionnaire. Survey responses from those participants who had graduated less than six months prior to the survey were collected in order to better understand motivations for becoming an RT and reflections on their training program. However, we did not include their responses in our findings related to employment rates and work profiles as we felt this would skew our results due to the limited opportunity these respondents had had to find employment. Characteristics of the survey respondents are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

At the end of the survey, respondents were invited to provide their contact information if they wished to receive a copy of the study results, or were interested in participating in an interview (component 2) and/or complete a follow-up survey. In 2015, we sent a brief follow-up questionnaire consisting of 28 questions to participants who completed the 2014 version and consented to be recontacted in this way. The follow-up questionnaire focused on any changes in the work situation of the participants over the preceding year.

Survey data analysis

Data collection and analysis for this project were conducted in two phases (2014 and 2015). In both years, we entered questionnaire data into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, 2011) to generate descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations (SD), and percentages. We then created tables and graphs to present the most pertinent results.

Component 2: interviews

Interview development

In the second component of the project, we employed a qualitative description approach [Citation22] to seek in-depth understanding of RTs’ experiences and perceptions related to their career trajectory and current employment situation. We developed the interview guide based on a review of the literature, the research team’s experiences in rehabilitation capacity building projects, and discussions with instructors in an RT training program. Four instructors from an RT training program in Haiti provided feedback on the provisional version of the interview guide and we made modifications based on their input. The interview guide included questions about the RTs’ motivations to undertake training in the rehabilitation field, their process of seeking work, their perceptions of the alignment of their training with their current employment, their experiences at work, and their future career plans.

Interview data collection

We conducted individual semi-structured interviews in French with 20 RT graduates (see ) who had completed the survey and were currently employed as RTs. We invited only working RTs to participate in an interview as we wished to gain further understanding of RTs’ perspectives related to their current occupational activities. To maximize the number of interviewees, we used a convenience sampling strategy. We subsequently invited by phone or email all individuals who indicated in their survey (component 1) that they were willing to participate in an interview. Characteristics of the interview participants are presented in .

The interviews were conducted in Haiti by francophone members of the research team (VC and ND in 2014, and EJ in 2015). Interviews ranged from 23 to 67 minutes (mean of 42 minutes) in duration and were transcribed by a member of the research team. Another member of the research team reviewed each transcript in order to ensure its accuracy.

Interviews data analysis

Following the nine interviews that were conducted in 2014, two team members separately coded the first two interviews. They met together with a third member of the team to develop a shared coding structure. Each of the remaining seven transcripts was coded by a single team member using constant comparative techniques. Each coded transcript was then reviewed by a second member of the team. During this process, several new codes were added to the coding structure as the analysis progressed. They then aggregated these codes into 19 conceptually linked categories through a collaborative process. The team then developed a provisional analytic structure based on a chronological progression from motivation to pursue a career in rehabilitation through to formulation of future career goals. In 2015, 11 additional interviews were conducted and analyzed using the coding structure. Again, a single investigator coded each transcript, and the coded transcripts were reviewed by a second member of the team. We then analyzed the full set of 20 interviews while considering how the new data added to, confirmed or challenged the analysis of the nine initial interviews.

Convergent data analysis

Throughout the analysis process, we sought to compare and contrast the results of the quantitative and qualitative components and consider how each component helped us to better understand and further contextualize our interpretation of the other.

Ethics

This project was approved by the Haitian National Bioethics Committee and the McGill University Faculty of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board. Survey respondents indicated their consent to participate as the first step of completing the questionnaire. Consent forms were signed by all interviewees prior to starting the interviews. Throughout this article, pronouns used for participants are alternated between male and female to decrease the chance of identification.

Results

In keeping with the convergent mixed methods design of this project, we present related elements of our qualitative and quantitative analysis in an alternating manner and based on a chronological perspective from motivations for becoming an RT to future career plans. In presenting the qualitative results, selected verbatim quotes from the interviewees are used to illustrate aspects of the analysis. Interview quotes were translated from French into English; back translation was used to verify that the meaning of the quotes was preserved during translation.

Motivations for becoming an RT (interviews)

Many interviewees expressed that there are important limitations in the rehabilitation services available for individuals with disabilities in Haiti. An interviewee who worked part-time with an NGO in a hospital’s outpatient department reported that for some Haitians the reality may be bleak: “When someone has a stroke […] He is confined to bed for a long time. Afterwards, he dies.” (P11). Interviewees related their choice to pursue training in the rehabilitation field to these gaps in services and the desire to contribute to their communities. The 2010 Haiti earthquake was a particularly important impetus for many of the interviewees’ decisions to embark on a career in rehabilitation, with 13 of the 20 interviewees describing the earthquake as an important factor in their decision to study to become an RT. Interviewees reported that following the earthquake, the situation in Haiti changed significantly including a much higher number of individuals who were living with a newly acquired disability. An interviewee who provided community-based services through an NGO, including assessing needs of persons with disabilities and referring them to relevant services, reported that while volunteering after the earthquake: “I became aware of the lack of professionals, either doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, or physical therapists.” (P2). She described how this realization about the needs in her community and the lack of professionals available to meet them led her to pursue training as a RT, and is reflected in statements made by other RTs who related their career choice to the possibility of providing tangible help to people in their community.

Although reasons for involvement in the rehabilitation field varied amongst interviewees, the desire to help those in need was a common goal that was expressed by 15 of the interviewees. There was also a widely shared perception across all interviewees that expanding the rehabilitation workforce in Haiti by training local rehabilitation providers was an important objective. An interviewee described his interest in rehabilitation in the following way:

Because I don’t like when people die, I like when people live. Even if we can’t live for a long time, I prefer that people can live without suffering. I don’t like to see people suffering, and that is why I like rehabilitation very much. (P11)

For another interviewee, the decision to pursue RT training was prompted by her goal to help an acquaintance with special needs. Other motivations included improving one’s overall level of knowledge, having a job that provided a good income, and pursuing a course of study that was inexpensive. An interviewee who was self-employed, and who mainly treated orthopedic and neurology patients, described her overall satisfaction with the training program stating that it was a “Really good start for me!” She noted, however, that education must be continuous “… across the entire lifespan” (P18).

Reflections on training program (interviews)

When discussing their program’s curriculum, 17 of the interviewees stated that the training they received provided a solid base for working in the rehabilitation field or for pursuing further education. There were several interviewees, however, who identified gaps. An RT who worked for an NGO described how he sometimes felt unprepared to treat certain complex cases, noting that in their training they were given a “minimum of competencies needed to intervene in different situations, and in different domains. In the sense that, we can’t intervene, even though we can see the problem.” (P2) These limits often reflected the constrained scope of practice of RTs. Overall, however, the interviewees described confidence in their abilities following completion of the program. For example, an interviewee who conducted a household survey and provided treatment to stroke, paraplegic and amputee patients in a community setting stated: “I feel very comfortable. I feel comfortable with the training program that I took. Really, I feel good because we practice the right way. I feel very comfortable while working with patients.” (P6). Peer and patient feedback, training experiences and comparison with graduates from other programs were cited as sources for these feelings of self-confidence. Five interviewees reported that the training on anatomy and patient evaluation were the modules that they found most useful for their clinical practice.

An issue related to the training programs that was raised by interviewees was their expectation that there would be official recognition for their training and credentials following their graduation. However, official recognition had yet to take place. An interviewee who worked in an NGO-run hospital, primarily with stroke patients, reported that “I, we were expecting to receive a diploma recognized by the state.” (P7). A second interviewee who worked for an NGO in community and hospital settings emphasized the importance of this recognition, saying: “Because here in Haiti, the certificates carry weight, it counts. […] Having a diploma is very important.” (P15). The lack of official recognition was seen as a limitation of the training programs by several interviewees.

Finding work (interviews)

While all of the interviewees were working at the time the interviews were conducted, their experience of seeking and applying for work was quite varied. The duration required for the interviewees to find employment ranged from already having a job offer before the program started to being hired 10 months after graduation. Regardless of the duration required to find work, most interviewees expressed relative ease in finding work, although several described challenges of not working for many months as they were searching for paid work. Interestingly, even if many interviewees stated that while their own process of finding work had not been difficult, they perceived the process as challenging for their peers. An RT who worked in an NGO-run clinic, and who reported that his clinical practice focused on amputees, described this situation in the following way:

I say easy because I finished, in fact, I received my diploma in October and then I started working in November […] But for my colleagues … it was not the same […] that is to say that it took them November, December, about six months to find a job. And then others still currently have not yet found work. So, it is not the same thing…. I imagine that it is not easy for them. (P1)

Also important to note is that close to one-third of the interviewees found work with the NGO that had managed their training program. Of these, three described the NGO as instrumental in their success in finding work. Similarly, other interviewees stated that having contacts in the healthcare sector was vital to finding work, such as connections from clinical rotations and training experiences. Although all interviewees stated that they had a professional occupation at the time of the interview, several had volunteer positions or were receiving an honorarium for their work, but not a salary. For example, an interviewee said that he searched for work for six months only to find a position as a volunteer without salary. Although most interviewees mentioned ease in finding work, they still cited competition for limited jobs as a challenge. This context is reflected by an interviewee who worked in a health promotion role for an NGO, yet hoped to find other employment where he could apply his clinical knowledge more directly. He stated that: “I have a lot of expectations but I know that work is not easy [to find] in Haiti” and “It is not easy because there aren’t a lot of rehabilitation centres in Haiti.” (P20). Two of the interviewees noted that despite the multiple RT training programs in Haiti, there has not been a corresponding increase in jobs for RTs, a situation that made finding work more challenging.

Employment rate and time delay prior to finding work (survey)

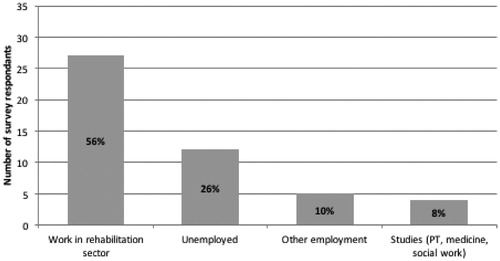

Of the 48 RTs who completed the questionnaire more than six months after their graduation, 30 (63%) had found work in rehabilitation (26 survey respondents who had graduated less than six months prior to completing the survey are not tallied here due to the short time interval in which they could have found employment). Three of these 30 RTs became unemployed between 2014 and 2015 giving an employment rate of 56% in 2015 (see ). Four questionnaire respondents were pursuing studies in a health-related field; two of them were studying physical therapy outside of Haiti.

Figure 3. Chart showing the work situation in June 2015 of the participants who completed the survey at least 6 months after graduation (n = 48).

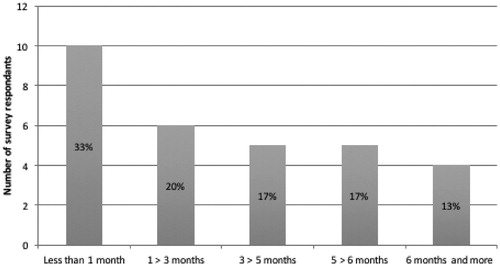

As illustrated in , amongst the participants who answered the questionnaire more than six months after graduation, more than half found work in the rehabilitation sector, typically in the first three months following their graduation. When including all graduates who completed the questionnaire three months after graduating but excluding those who were pursuing studies in physical therapy (n = 72), comparative analysis of questionnaires in 2014 and 2015 indicates that the 2015 group did not find work as quickly as the RTs who graduated in the previous years. In 2014, 44% (16/36) found work in rehabilitation within the first three months of graduation while only 14% (5/36) did so in 2015 (two sample z-test: difference between 11% and 51% [95%CI]).

Figure 4. Time elapsed prior to finding employment for those who graduated more than 6 months prior to completing the questionnaire (n = 30).

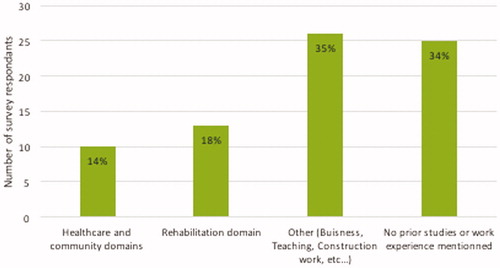

Of the 74 respondents, one third were working or studying in the health or rehabilitation sector immediately prior to beginning their training, as illustrated in . Respondents’ background and experience were associated with finding employment upon graduation as 54% of RTs who found jobs in the rehabilitation sector (19 of the 35 working RTs) had previous experience in the rehabilitation or health care sector prior to their RT studies (Chi-square: 12.03; p < .001).

Current employment (including availability of supervision)

Survey

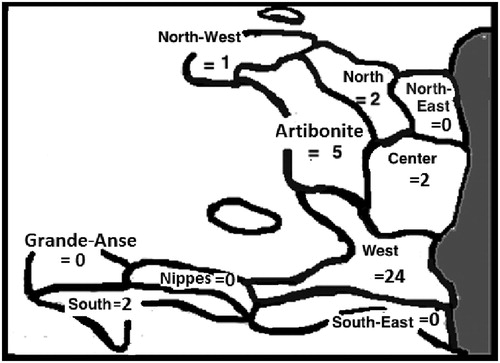

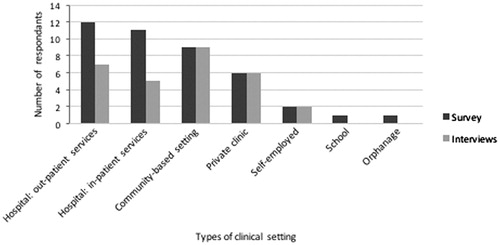

illustrates the distribution across the country of those questionnaire respondents who had found work (n = 35). More than 80% of these respondents were working in the department where their training program was located. For example, almost every RT trained in Port-au-Prince later found work in the West department of Haiti. More respondents worked in urban areas (26), with 14 reporting that they worked in a rural setting, and five who worked in both.

The private sector, especially NGOs, was the most common source of employment for survey respondents. Three of 35 respondents worked in the public sector at the time of completing the questionnaire (one respondent did not answer this question). Thirty-one technicians reported receiving an income while two stated they received compensation for transport, food, and lodging. Two participants reported working as volunteers.

While the majority of questionnaire respondents reported working in more than one setting, hospitals were the most common (). Most worked with a diversified clientele in terms of age and pathology. Working with all age groups, ranging from infants to the elderly, was mentioned by 26 of the 35 respondents who were working at the time they completed the survey. On average, respondents reported seeing 7.6 ± 3.2 (SD) different categories of clinical conditions in their practice, with neurology being the most common. Working hours varied considerably, ranging from 6 to 52 h per week, with mean hours worked per week of 34.6 ± 13.9 (SD).

Figure 7. Type of setting where RTs are working (n = 35 questionnaire respondents and n = 20 interview participants)*. *Several study participants reported that they worked in more than one setting.

The level of supervision and professional support available during their current employment also varied. Twenty-five of the 35 questionnaire respondents who are working or were working, reported being supervised by a PT and/or OT, while five reported that their supervisor had a different profession, for example, doctor, nurse, social worker, or service coordinator. Eight of the 35 RTs reported that they were not supervised.

Interviews

The interviewees worked in a range of clinical settings. Similar to the questionnaire respondents, most of the interviewees were employed in a hospital. More than half of the interviewees described their work as entirely or partly based in the community, a proportion which is higher than the one-fifth of questionnaire respondents who described working in a community setting (see ).

In comparison to the questionnaire results, five interviewees reported working without supervision, five reported having limited supervision, and 10 reported being supervised. Sources and styles of supervision differed amongst the interviewees; for example, several interviewees reported working closely with a supervising PT, while others mentioned that their supervision consisted of participating in rounds each morning or in weekly team meetings to discuss difficult cases.

Work responsibilities and roles of interviewees included direct clinical treatment, as well as data collection. Hands on interventions discussed included muscle strengthening, joint mobilizations, stretching, gait training, balance training, prosthetic training, and massage therapy. Also, interviewees identified arterial tension measurement, speech therapy, wheelchair and seat positioning, washing patients, and patient education as being part of their responsibilities. Collection of data, such as through household surveys, was a task discussed by five of the interviewees, and four described this as their main responsibility. These interviewees reported that they expected to have more clinical responsibilities in the future; however, their current tasks were not specific to the RT training they received. Interviewees also reported non-rehabilitation related tasks; for example, three of the interviewees reported working as a translator as part of their responsibilities.

Four participants described referring patients to other services, including for medical care, orthoses, prosthetics, nutrition and assistive devices. They also participated in patient education, and training for other care providers. For example, a participant provided training to community workers on the role of an RT and which individuals they should refer to her. Eight of the participants discussed documenting their assessments or treatment plans. Two of the participants implemented treatment plans that were developed and written out by their supervisor who was a PT. The participants described using a range of equipment in their treatment sessions including donated equipment received through an NGO. A participant who worked with an NGO in both a clinic and in the community reported that she and her colleagues found other ways to work without material: “We found ways to work without [rehabilitation] material. We are creative. We work with what is available.” (P7).

Interviewees discussed several common concerns regarding their clinical practice. Four described how they sometimes found the perceptions of patients to be a source of challenges. For example, interviewees expressed that some members of the population thought that NGOs and the RTs that they employed should bring food or money to their patients, and not just provide rehabilitation services. This situation led to feelings of discomfort for these RTs. An interviewee who worked mostly with amputees reported that “It’s people that sometimes want money to feed themselves since they are not working or to feed their children.” (P1). While financial issues are challenging in Haiti, an interviewee who was self-employed reported that she was able to adapt to this issue by allowing people to pay what they could afford for her professional services although it put financial strain on her. A specific challenge voiced by one of the interviewees who worked for an NGO providing community-based care, was that she was expected to work one day per week in a rural region and this required walking for several hours to visit clients in areas that did not have roads, running water or electricity.

Interviewees expressed a range of feelings related to remuneration. While one expressed satisfaction with his salary, four mentioned being dissatisfied. An interviewee noted the reality of working in Haiti and described her perspective that: “Well, the (work) conditions are not bad but the salary is very, very bad.” (P19). Another participant discussed that his biggest issue related to compensation was the fluctuation of his income month-to-month depending on the availability of work.

Involvement in continuing professional development activities was reported by the majority of interviewees. All are seeking to get further certification and training. Seven interviewees described the Internet and distance education as means for finding new information and solutions to work challenges.

Plans for the future (interviews)

While most interviewees expressed enjoyment of their current work positions, every participant described aspirations to alter their career path to some extent in the future. Most are interested in continuing their education and becoming PTs. A participant who worked with an NGO reported her goal was to “find an opportunity to study, to participate in continued education, not at the level of a rehabilitation technician, but rather in physiotherapy, or study in a foreign country that is not too far away” (P8). A few interviewees discussed the possibility that a physiotherapy school would be established in Haiti, and expressed excitement about the possibility of being able to study in their own country. This situation was described in the following way by a participant who worked with an NGO primarily with adult and pediatric neurology patients: “Just to establish a school of physiotherapy in Haiti. In order for rehabilitation technicians to continue, rather than restart […] We could have a continued education after receiving the diploma as a rehabilitation technician, and then get a diploma as a physiotherapist” (P3, who had been working as an RT for less than one year).

Others discussed at least temporarily leaving Haiti to study since no programs were offered in Haiti at the time the interviews were conducted. Studying to become an OT, nurse or physician was also discussed by several interviewees.

In addition to further educational goals, several interviewees discussed entrepreneurial or managerial ambitions, most often related to operating their own clinic, and one interviewee aspired to create an amputee soccer team. A participant stated that she hoped to build a rehabilitation clinic in her hometown where there currently are no rehabilitation services available. Two interviewees also described how advancement of the rehabilitation sector would help improve the overall healthcare system in Haiti.

Discussion

The questionnaire and interview results provide a portrait of the work profile, employment trajectory and perceptions of graduates from three RT training programs in Haiti. By drawing upon multiple data sources, understanding of this phenomenon is enhanced through triangulation.

The availability of paid employment for RTs was a source of concern for RTs who participated in the interviews. When questionnaire results are compared between 2014 and 2015, it appears that RTs who graduated in 2015 had more difficulty to find employment in the months following their graduation. One possible explanation is that the job market for RTs is becoming increasingly saturated, even though the need for rehabilitation services in Haiti has not decreased. Hence, it could be hypothesized that the lack of awareness of the RT profession within Haitian society, lack of regulatory structures for rehabilitation professions (e.g., standards and policies), and scarcity of funding for rehabilitation services, may hinder the availability of RT positions in the health system. Bigelow also reported challenges for RTs who graduated in 2001–2 to find work in Haiti [Citation1]. However, the employment rate appears to have improved somewhat since that time as Bigelow found only 45% of technicians who had graduated at least 6 months prior to the survey were working, compared to 56% in our survey. Concerns regarding the sustainability of the rehabilitation field in Haiti are also raised by our findings as most of the current work positions are funded by NGOs. Further expanding publicly funded rehabilitation services will be important to address the reliance on external agencies.

The survey results also suggest that RTs, and likely rehabilitation services, are not evenly distributed across the country. Most of the survey respondents work in the West department of Haiti which is the most populous department and where the capital, Port-au-Prince, is situated. Also, graduates who completed the questionnaire from these RT programs are working in only six of the 10 departments of the country. It appears that RTs are most likely to find work in the department where they were trained; hence, strategically choosing the location of future training programs could help target areas with fewer rehabilitation services [Citation1].

Both the survey and the interview results indicate that the most common conditions treated by RTs were neurological conditions (especially cerebrovascular accidents) and amputees. The frequency with which amputees were followed by RTs in Haiti appears to have increased as only 25% (8/32) of RTs surveyed by Bigelow in 2003 [3] worked with amputees compared to 82% (27/33) of employed survey respondents in this study. The increased number of amputees seen clinically could partially be due to the 2010 earthquake. Indeed, our survey results support research by Tataryn and Blanchet indicating that prosthetic and orthotic services have grown significantly since the earthquake [Citation1].

Supervision is an area where the qualitative and quantitative findings offered different perspectives. While the survey results suggest that more RT graduates were supervised than in the past [Citation3], the interviews offered a more nuanced description of the amount and degree of supervision available, with sometimes quite limited supervision provided and sometimes by a professional who was not a PT, OT or physician specialized in rehabilitation. One possible explanation for the supervisory situation may be the critical imbalance between the number of rehabilitation professionals with advanced training in Haiti and the number of RTs requiring supervision. Given these realities, further discussion regarding the most feasible and effective modes of supervision for RTs in Haiti is warranted, with the goal of ensuring that patients are safe and RTs are adequately supported in their clinical practice.

Though survey data suggests participants enjoy their positions as RTs, all of the interviewees discussed plans for further education. Most expressed ambitions to pursue studies in physiotherapy, either abroad or in Haiti. When the interviews were conducted, the interviewees were not aware of a physiotherapy school opening in Haiti. Since then, a physiotherapy program has been launched at l’Université de la Fondation du Dr. Aristide, as well as a physiotherapy and occupational therapy program at l’Université Episcopale of Leogane. Plans by RTs to join other professions, as well as the initiation of new PT and OT training programs, raise several questions. The difficult job market, lack of official recognition of the RT professional designation, and challenging work conditions experienced by some RTs might contribute to RTs’ desire to become PTs. However, it remains unclear what effect the arrival of newly trained PTs will have on the job prospects of RTs and the sustainability of RT training in Haiti, though additional PTs may well contribute to filling the need for RT clinical supervision.

Limitations

As study data were collected over a 13-month period, several limitations noted during early phases of data collection were addressed as the study progressed. Challenges were noted related to understanding of some questions in the questionnaire and during the interviews. All of the participants’ first language was Creole and both the survey and interviews were completed in French. In order to address this, the survey and interview guide were reviewed by several Haitians and expatriate rehabilitation professionals involved in the training of RTs in Haiti. This led to the reformulation or retraction of several questions to enhance clarity. Miscommunication regarding the purpose of the interview also occurred in some cases. It appeared that some interviewees hoped that participating in the research interview might lead to an offer of employment, and this might have distorted some of their answers despite efforts by the interviewer to clarify the purpose of the interview.

Future research

As the rehabilitation sector in Haiti continues to evolve over the coming years, it would be beneficial to conduct further research to examine how services for patients and opportunities for rehabilitation professionals (including RTs and, in the future, PTs) change over time. It will be important to see how the addition of new physiotherapy schools will impact the availability of work for RTs and the supervision they receive. It would also be interesting to further investigate the reasons why graduates have intentions to alter their paths away from working as RTs. Furthermore, research aiming to develop professional guidelines and standards for RTs may help in better defining their respective roles and responsibilities as rehabilitation providers within a multidisciplinary team involving supervisors such as PTs and OTs. Also of interest is research aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of RTs in responding to disability and improving patient outcomes across different clinical settings in Haiti. As our research highlighted the RTs’ desire for continuing professional education as they moved forward in their careers, it would be valuable to evaluate the provision of this training, and its contextual relevance and alignment with the RTs’ learning needs.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into the experiences of RTs who graduated from three training programs in Haiti, and how the rehabilitation sector is evolving. Currently, NGOs play a central role in both training RTs and employing them upon graduation. This reliance on the contribution of NGOs raises concerns related to sustainability and the possibility of expanding rehabilitation services. Unequal distribution of RTs across the country also suggests important geographical variation in access to services. The types of patients treated by RTs appear to have changed over the past decade, with more RTs reporting that they treat amputees as part of their clinical work.

The RT training programs represent an important mechanism to enhance rehabilitation human resources in Haiti. However, challenges remain, including achieving official recognition of the RT training and the availability of RT jobs, especially in the public sector. The results of this study provide insight into rehabilitation capacity building in Haiti, and may be relevant for individuals and organizations involved in establishing similar programs in other countries where the rehabilitation sector is also in the process of being developed.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants for giving their time and sharing their experiences, as well as to the coordinators and leadership of the three RT training programs for supporting this project. We thank the Handicap International team, Laure Ancellin (masseur-kinésithérapeute), Franshy P. Dorcimil (MD), Johanne Eliacin (PT), Denise Marcajoux (PT), Joseph Emmanuel Jr Philippe (PT), and Axelle Senelonge (OT), for providing feedback on provisional versions of the survey and interview guide. We also thank members of the Global Health, Ethics and Rehabilitation Works-in-Progress group at McGill University for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This study was completed as part of the Master’s research projects in the professional Master’s programs in OT and PT at McGill University. Funding for this project was provided by the McGill School of Physical and Occupational Therapy and the McBurney Advanced Training Program of the McGill Institute for Health and Social Policy. Matthew Hunt is supported by a Research Scholar salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé.

Disclosure statement

Nancy Descôteaux and Matthew Hunt have volunteered as instructors in the Handicap International RT training program in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. ND previously worked as a rehabilitation educator within the Health Volunteers Overseas RT training program in Haiti during March 2003, January 2004 to November 2004, and August 2010, and with Handicap International in Ivory Coast and Pakistan. David Charles has been involved in the supervision of Health Volunteers Overseas rehabilitation technicians at the Albert-Schweitzer Hospital when he held the role of rehabilitation services manager between 2009 and 2012.

Note

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The title of rehabilitation technician is used in this text to describe all persons trained in an entry-level rehabilitation training program between nine months and two years in duration.

References

- Parker K, Adderson J, Arseneau M, et al. Experience of people with disabilities in Haiti before and after the 2010 earthquake: WHODAS 2.0 documentation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1606–1614.

- Tataryn M, Blanchet K. Evaluation of post-earthquake physical rehabilitation response in Haiti, 2010—a system analysis. Humanit Exchange Mag. 2012;54:33–34. Available from: http://www.odihpn.org/humanitarian-exchange-magazine/issue-54/the-rehabilitation-response-in-haiti-a-systems-evaluation-approach. Accessed 2015 Sep 21.

- Bigelow JK. Establishing a training programme for rehabilitation aides in Haiti: successes, challenges, and dilemmas. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:656–663.

- Klappa S, Audette J, Do S. The roles, barriers and experiences of rehabilitation therapists in disaster relief: post-earthquake Haiti 2010. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:330–338.

- Danquah L, Polack S, Mactaggart I, et al. Disability in post-earthquake Haiti: prevalence and inequality in access to services. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:1082–1089.

- Jacobson E. An introduction to Haitian culture for rehabilitation service providers. Buffalo (NY): Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange; 2003.

- Handicap International [Internet]. France: Haiti: Turning disaster into strength—after the earthquake: two years of action; 2011 July 12; [cited 2015 Sep 15]. Available from: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/haiti_turning_disaster_into_strength.pdf

- Landry MD, O’Connell C, Tardif G, et al. Post-earthquake Haiti: the critical role for rehabilitation services following a humanitarian crisis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1616–1618.

- USAID [Internet]. Request for applications number 521-10-033: Haiti rehabilitation and reintegration of person with disabilities program; 2011 March 14; [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId =78693

- Bureau Secrétaire d’État pour l’intégration des personnes handicapées [Internet]. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: La SHP, pour la promotion de la physiothérapie en Haïti; 19 juillet 2016 [cited 2016 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.seiph.gouv.ht/la-shp-pour-la-promotion-de-la-physiotherapie-en-haiti/

- Campbell DJT, Coll N, Thurston WE. Considerations for the provision of prosthetic services in post-disaster contexts: the Haiti Amputee Coalition. Disabil Soc. 2012;27:647–661.

- Dunleavy K. Physical therapy education and provision in Cambodia: a framework for choice of systems for development projects. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:903–920.

- Kay E, Kilonzo C, Harris MJ. Improving rehabilitations services in developing nations: the proposed role of physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 1994;880:77–82.

- Leavitt R. The development of rehabilitation services and community-based rehabilitation: a historical perspective. In: Leavitt R, editor. Cross-cultural rehabilitation: an international perspective. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1999. p. 99–112.

- Horobin H, Naughton CN. ADAPT newsletter: “Training and education edition”. London (UK): CSP Interest Group; 2008.

- Wickford J, Hultberg J, Rosberg S. Physiotherapy in Afghanistan—needs and challenges for development. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:305–313.

- Healing Hands for Haiti [Internet]. Salt Lake City, Utah: points saillants de notre histoire; [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.healinghandsforhaiti.org/AboutUs/History/tabid/63/language/fr-FR/Default.aspx

- Health Volunteers Overseas, Hopital Albert Schweitzer. Demande de reconnaissance de certificat de technicien en réadaptation et curriculum de formation technique adressé au Département de Formation et de Perfectionnement des Sciences de la Santé/Ministère de la Santé publique et de la population (département de l’Artibonite). Deschapelles, Haiti; 2014. Unpublished.

- Handicap International [Internet]. Silver Spring, MD: Rehabilitation Technicians Graduate in Haiti; [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.handicap-international.us/rehabilitation_technicians_graduate_in_haiti

- Loma Linda University [Internet]. Loma Linda, CA: Rehabilitation Technician Training Program—Certificate; [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://llucatalog.llu.edu/allied-health-professions/rehabilitation-technician-training-certificate/#text

- Handicap International, Health Volunteers Overseas, Loma Linda University. Proposition de curriculum standardisé pour les formations de techniciens en réadaptation adressée au Ministère de la Santé publique et de la population. Port-au-Prince, Haiti; 2014. avril.Unpublished.

- Gedeon MA, editor. La formation spe´cialise´e en Physiothe´rapie à l’UNIFA; 5ièmee Confe´rence Charles Me´rieux – Sante´ Globale: Les Enjeux Haïtiens; 2015 Feb 23; Port-au-Prince. Haiti: Université de la Fondation Dr Aristide et La Fondation Merieu; 2015. 10 p.

- Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, et al. Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:52.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2013.

- LimeSurvey Project Team/Carsten Schmitz. LimeSurvey: an open source survey tool; 2015. Hamburg, Germany: LimeSurvey Project. Available from: http://www.limesurvey.org