Abstract

Purpose: The aim of the current study was to examine the effects on sickness absence of multimodal rehabilitation delivered within the framework of a national implementation of evidence based rehabilitation, the rehabilitation guarantee for nonspecific musculoskeletal pain.

Method: This was an observational matched controlled study of all persons receiving multimodal rehabilitation from the last quarter of 2009 until the end of 2010. The matching was based on age, sex, sickness absence the quarter before intervention start and pain-related diagnosis. The participants were followed by register data for 6 or 12 months. The matched controls received rehabilitation in accordance with treatment-as-usual.

Results: Of the participants, 54% (N = 3636) were on registered sickness absence at baseline and the quarter before rehabilitation. The average difference in number of days of sickness absence between the participants who received multimodal rehabilitation and the matched controls was to the advantage of the matched controls, 14.7 days (CI 11.7; 17.7, p ≤ 0.001) at 6-month follow-up and 9.5 days (CI 6.7; 12.3, p ≤ 0.001) at 12-month follow-up. A significant difference in newly granted disability pensions was found in favor of the intervention.

Conclusions: When implemented nationwide, multimodal rehabilitation appears not to reduce sickness absence compared to treatment-as-usual.

A nationwide implementation of multimodal rehabilitation was not effective in reducing sickness absence compared to treatment-as-usual for persons with nonspecific musculoskeletal pain.

Multimodal rehabilitation was effective in reducing the risk of future disability pension for persons with nonspecific musculoskeletal pain compared to treatment-as-usual.

To be effective in reducing sick leave multimodal rehabilitation must be started within 60 days of sick leave.

The evidence for positive effect of multimodal rehabilitation is mainly for sick listed patients. Prevention of sick leave for persons not being on sick leave should not be extrapolated from evidence for multimodal rehabilitation.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Persistent nonspecific musculoskeletal pain and mental health problems are the most common causes of long-term sickness absence in Sweden and many other Western countries. Back and neck pain are extremely common, with a life-time prevalence of 70–80% in the general population [Citation1]. The majority recovers rapidly, but persons whose symptoms have not improved within three months of pain onset (5–10%) have a poor prognosis for spontaneous recovery [Citation2,Citation3]. Moreover, relapses are common [Citation4]. It is well recognized that psychosocial factors, such as dysfunctional beliefs and inadequate responses to pain as well as work place factors play a crucial role in the transition from acute to persistent pain [Citation5–7]. As a consequence, effective treatment must take both psychosocial and physiological factors in private life as well as at work into consideration. Return to work programs with multimodal rehabilitation offers such a comprehensive approach and is viewed as a promising option for rehabilitating persistent nonspecific pain. Multimodal rehabilitation has shown evidence of reducing symptoms and disability [Citation8,Citation9]. The effects on sickness absence and work return are less consistent, but several studies have demonstrated reduced sickness absence after multimodal rehabilitation [Citation10], while analyses of cost-effectiveness, including longitudinal follow-up studies [Citation11] and analyses of cost-effectiveness have been positive [Citation12]. Persons with less complex chronic pain conditions may benefit from unimodal treatments, i.e., physiotherapy, exercise or cognitive-behavioral therapy [Citation13,Citation14].

Reducing sickness absence is a political priority and in Sweden a national program launched by the government for evidence-based rehabilitation – called the rehabilitation guarantee – was implemented in 2009. The aim of the rehabilitation guarantee was to reduce sickness absence and support return to work by offering access to evidence-based rehabilitation as an early intervention for persons suffering from nonspecific, persistent musculoskeletal pain – mainly back and neck pain – or mild to moderate mental health disorders. While persons with mental problems were offered psychotherapy, pain patients were offered multimodal rehabilitation. The implementation of the rehabilitation guarantee is described in detail in another publication [Citation15] but in brief, the introduction of the rehabilitation guarantee meant increased access to multimodal rehabilitation which was facilitated by generous economic compensation from the Swedish Government to the county councils. Multimodal rehabilitation was given in primary and specialized care. The current study was originally initiated by a commission from the Government to evaluate the effects of the rehabilitation guarantee on sickness absence. This paper reports the effects of multimodal rehabilitation on sickness absence.

Aim

The aim of the current study was to examine the effects on sickness absence of multimodal rehabilitation delivered within the framework of a national implementation of evidence based rehabilitation, the rehabilitation guarantee for nonspecific musculoskeletal pain.

Method

Design

This was an observational matched controlled study of patients participating in multimodal rehabilitation. All participants were followed by register data for 6 or 12 months after starting rehabilitation. The study was part of a project aimed at evaluating the effects and the process of implementation of the rehabilitation guarantee. The study design is in line with recommendations regarding evaluation of complex interventions [Citation16]. The process evaluation is published and described elsewhere [Citation15].

Procedure

To stimulate the implementation of the rehabilitation guarantee, the State allocated economic compensation to the county councils. To qualify for this compensation, each unit (i.e., primary health care unit or specialized care unit providing multimodal rehabilitation) had to register and report all individuals who started rehabilitation within the rehabilitation guarantee. The research group received register data for two cohorts within the framework of the present study. Cohort I comprised patients receiving multimodal rehabilitation from January to September 2009 and Cohort II from October 2009 to December 2010. Register data for Cohort I were incomplete. Three counties failed to report data, while some files lacked information about date of rehabilitation start or what kind of rehabilitation the patients received. These shortcomings can probably be explained by the fact that the rehabilitation guarantee was newly introduced and necessitated new ways of working [Citation15]. The evaluation of cohort I was due to the shortcomings not included in the present study but is available in a Swedish report [Citation17]. For cohort II, the research group received complete register data on patients who had undergone multimodal rehabilitation. Using personal identification numbers, data on sickness absence could be obtained from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. All people who live or work in Sweden and are of working age can receive economic compensation from the Social Insurance Agency if their work capacity is temporarily or permanently reduced for medical reasons after 14 days of sickness absence. The first 14 days compensation is paid by the employer. Sickness absence in the Social Insurance Agency’s registers is related to a main diagnosis, and it is possible to have multiple sub-diagnoses. Therefore, among the included rehabilitants there might be persons having more than one diagnosis. According to the system in operation at the time of the rehabilitation guarantee, sickness benefits could be received for a maximum of 364 days during a 450-day period. A permanent reduction in work capacity may result in people aged 30 or older being awarded a disability pension. Such pensions are not time-limited in Sweden; however work return among disability pensioners is rare, even after rehabilitation [Citation18].

Subjects

To be eligible for multimodal rehabilitation within the rehabilitation guarantee, individuals had to be of working age (18–67 years) and have nonspecific musculoskeletal pain for a minimum of three months due to one of the following diagnoses (ICD-10): M40–M43, M48–M54, M75, M79, R52. Moreover, individuals had either to be on pain-related sickness absence, or be at risk of long-term sickness absence. The rehabilitation guarantee did not include standardized measures for assessment and examination of patients, consequently the selection of patients was on the discretion of the referring physician and the clinics involved.

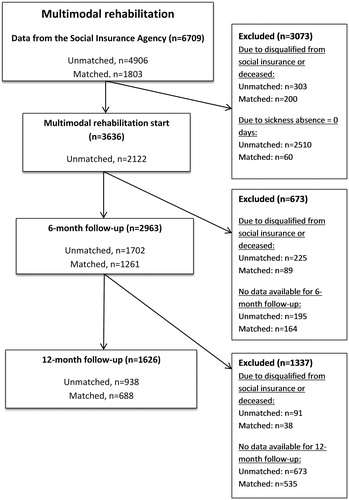

Matching was used to obtain a control group for comparative purposes. Matching was carried out by the Social Insurance Agency, using the national registry of sickness absence as a sample frame. Participants without sickness absence could not be assigned controls (see ). Hence the sampling frame for matching was all Swedish citizens who were on sickness absence during the same period and for the same diagnosis as the patients and not identified in the county’ registries as receiving multimodal rehabilitation within the rehabilitation guarantee. The patients were randomly assigned 1–3 matched controls and the matching was carried out to obtain similarities concerning: (a) age (±5 years); (b) sex; (c) amount of sickness absence in the quarter before inclusion (±30 days); and (d) pain-related diagnosis. These are some of the factors that have been identified in the literature as being most influential for sickness absence/return to work [Citation19,Citation20]. If the matching yielded a maximum of three controls, all were selected. If there were more than three matches the controls were selected randomly.

No information regarding previous treatments was available for either patients or controls.

Intervention

The rehabilitation guarantee stipulated that multimodal rehabilitation should be given by teams of at least three different health professionals, of whom two should be a medical doctor and a behavioral scientist. The others are often physiotherapist, occupational therapist and nurse. The program should include activities carried out on a regular basis (2–3 times a week) for a period of at least six weeks, with 8 up to 10 participants. It was stressed that the program should have a non-specified psychological base, in order to support patients adopting a self-management approach. The program should also include physiotherapy and education in pain and coping strategies. Multimodal rehabilitation could be given by private or public health care and was offered both in primary care and specialized pain units. It was not specified if the clinics should be of primary or specialized care. The purpose with the rehabilitation guarantee was that the patients should receive the same care regardless of type of clinics and it was assumed in the agreement between the government and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions that even the rehabilitation teams at the primary health care units should provide specialized care. Irrespective of the exact nature of the rehabilitation, participants only paid a small fee which is the same for all patients receiving care in Sweden.

Control group

The matched control group received care and rehabilitation in accordance with treatment-as-usual in Sweden. We did not have any further information about the content in treatment as usual. Based on the county council registers, we have information that no member in the control group underwent multimodal rehabilitation as part of the rehabilitation guarantee.

Statistical analyses

The outcome was registered sickness absence after multimodal rehabilitation. Partial sickness absence (25%, 50%, 75% of full time) and partial disability (25%, 50%, 75% of full time) were transformed and standardized to whole days. Partial and full disability pension was calculated as number of sick days. Sickness absence during follow-up was examined using linear model with repeated measurements and the relative risk of receiving a full disability pension was evaluated using modified Poisson’s regression with the intervention group as reference category. When calculating the risk of being granted disability pension at the 12-month follow-up, persons on partial or full disability pension the quarter before rehabilitation start were excluded. Age, sex, and sickness absence the quarter preceding rehabilitation start were included as covariates in all analyses. Sickness absence during the first month of rehabilitation is not included in the analyses in order to minimize the difference between attending a rehabilitation program which often requires sick leave and the controls who did not attend extensive rehabilitation in the rehabilitation guarantee. The outcome analyses are based on “intention to treat”, hence all individuals who started rehabilitation within the rehabilitation guarantee were studied, irrespectively of whether they completed rehabilitation or not. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

To ensure that the results were independent of the matching procedure, coarsened exact matching was also employed [Citation21,Citation22]. If the results of the Social Insurance Agency matching and the coarsened exact matching differed significantly they both are given; otherwise only the results of the Social Insurance Agency matching are presented.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Ethical Committee in Stockholm (Reference 2009/1750-31/1).

Results

The records received from the counties included 6709 individuals. The files were complete, all counties were represented and very few internal missing data were observed. It was decided that the follow-up period should be at least 6 months. Thus subjects were excluded from analyses if they had a shorter follow-up time than six months, if they were disqualified from receipt of the social insurance (i.e., reached maximum days of compensation), or if they died (). Number of excluded were: N = 3073 at rehabilitation start; N = 673 at 6-month follow-up and N = 1337 at 12-month follow-up. About 2/3 of the rehabilitants received multimodal rehabilitation in primary care and 1/3 in specialized care.

The participants’ background characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Participants’ background characteristics.

Registered sickness absence

Fifty-four percent of the participants (N = 3636) had registered pain-related sickness absence the quarter before the rehabilitation started. Disability pensions were responsible for a substantial part (40%) of the sickness absence.

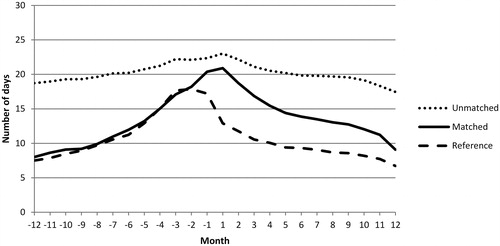

The pattern of sickness absence is illustrated in . The figure shows the mean number of days on sickness absence per month, one year before and one year after rehabilitation start. As shown, the pattern is similar among rehabilitants and controls during this period, although the control group seems to have a more rapid reduction in sickness absence than the rehabilitants at follow-up. A total of 45% of the rehabilitants were assigned matched controls, in the Social Insurance Agency register. The sick listed, unmatched rehabilitants differed from the matched rehabilitants in having more sickness absence both before and after the interventions, with only minor changes in response to the multimodal rehabilitation.

Figure 2. Mean number of days of registered sickness absence for rehabilitants and the matched controls.

Among the unmatched rehabilitants, 62% were on disability pension, and of those with disability pension, 57% had full time disability pension. About 98% of the unmatched rehabilitants lacked a diagnosis in the Social Insurance Agency register. However, from the county councils’ registration of participants receiving multimodal rehabilitation, it is most likely that the unmatched rehabilitants had pain-related diagnoses.

Group differences in sickness absence were tested statistically using linear model with repeated measurements, controlling for the possible effects of age, sex and sickness absence the quarter before inclusion. Beta coefficients and parameter estimates are given in . The results showed that the control group – despite having a similar amount of sickness absence as the rehabilitants before inclusion – had significantly lower rates of sickness absence at follow-up. The first quarter after the rehabilitation start rehabilitants had an average of 21 more sick days than the control group, and at the fourth quarter post-rehabilitation the difference was nearly 10 days more for rehabilitants. The length of sickness absence before rehabilitation was also an important independent factor affecting the outcome. Rehabilitants and controls with more than 60 days of sickness absence had approximately one month more sickness absence per quarter at follow-up compared to those with shorter spells of sickness absence. Furthermore, higher age was statistically associated with increasing amounts of sickness absence at follow-up. There were no differences between men and women in sickness absence patterns. When analyzing the difference in number of days on sickness absence at the 12 month follow-up between rehabilitants receiving multimodal rehabilitation in primary or specialized care, there were no significant differences.

Table 2. Average differences (I – C) in number of days of sickness absence per quarter after rehabilitation, with parenthesized confidence intervals (95%) for the multimodal rehabilitation group (I), compared with the control group (C).

Risk of disability pension

The risk of being in receipt of a disability pension at the 12-month follow-up was assessed using modified Poisson regression analyses. Included in these analyses were participants who were on sickness absence – but did not have a disability pension – the quarter before the rehabilitation started (). The results showed that the control group had a 2.4 (RR 2.4, CI 1.3; 4.5, p = 0.006) times higher risk of being in receipt of a disability pension during the 12-month follow-up compared to the rehabilitants. When sickness absence the quarter before rehabilitation start and age at rehabilitation start was included as explanatory variables, the relative risk did not change.

Table 3. The relative risk of being granted a full disability pension 12 months after multimodal rehabilitation start, risk ratios with parenthesized confidence intervals (95%).

Rehabilitants at risk of sickness absence

The aim of the rehabilitation guarantee was not only to reduce but also to prevent sickness absence. In multimodal rehabilitation, 928 rehabilitants did not have any registered sickness absence 12 months before the rehabilitation started. Of these, 28% (N = 260) began a period of sickness absence in the first quarter after rehabilitation, and at the fourth follow-up quarter, 14% (N = 130) were still on sickness absence.

Discussion

The rehabilitation guarantee was implemented nationwide in Sweden to reduce sickness absence by promoting evidence-based rehabilitation at an early stage of the sickness absence process. The main findings of this observational matched control study indicated that (1) multimodal rehabilitation appears not to reduce sickness absence compared to treatment-as-usual; and (2) participation in multimodal rehabilitation was related to a reduced risk of being granted a disability pension compared to treatment-as-usual. Furthermore, (3) the goal of offering early interventions was rarely fulfilled, since many of the participants were already on long term sickness absence or had disability pensions.

The positive effects of multimodal rehabilitation revealed in previous research are mostly related to reduction of symptoms and improved disability, less is known about the intervention’s effect on sickness absence. However, there are some studies reporting positive results for decreased sickness absence among persons participating in multimodal rehabilitation [Citation10,Citation11]. The lack of effect on sickness absence might also be explained by the lack of workplace interventions included in the rehabilitation guarantee. As shown in the process evaluation, the goal of return to work became less pronounced during the implementation process. Care and health were more often described in the county councils’ documents used to disseminate information about the rehabilitation guarantee [Citation15]. Workplace interventions are defined as interventions that take place fully or partly at the employee’s workplace, or involve delivery of the intervention by or in direct contact with the employer or a representative of the employer [Citation23]. When combining multimodal rehabilitation and workplace interventions, positive effects for sickness absence have been reported [Citation24,Citation25]. Thus, workplace interventions have to be considered as a part of multimodal rehabilitation programs in future research.

The fact that the sickness absence of the control group decreased more rapidly than that of the multimodal rehabilitation group raises several questions, since numerous well-controlled clinical trials have indicated better work-related outcomes for multimodal rehabilitation than for no treatment [Citation26] and unimodal rehabilitation [Citation8,Citation26]. Our register data provided minimal information about rehabilitants and controls; we therefore lack information about their health status other than their diagnoses and sickness absence histories. One explanation may therefore be that rehabilitants actually had more severe problems, or more comorbidity, than non-rehabilitants, and therefore had a worse prognosis for recovery. However, matching was based on the most prominent risk factors for sickness absence, mainly the length of previous sickness absence, and in another observational study – employing a similar matching technique – we did not find any advantages in health in the control group [Citation27].

Although early interventions are often promoted [Citation28], little is known about the effects of using multimodal rehabilitation as a mean of preventing sickness absence. In the present study, the goal of offering early interventions was rarely fulfilled, since most of the rehabilitants already were on long term sickness absence or was granted disability pensions. The finding could be explained by the rehabilitation guarantee’s inclusion criteria stating that rehabilitants should have nonspecific musculoskeletal pain for at least three months, which has to be considered as a wide inclusion criterion. As described in the process evaluation of the rehabilitation guarantee, lack of well-defined criteria for selection of patients, and unspecified treatment modalities were barriers to the implementation of multimodal rehabilitation and thus possible explanations to the inclusion of rehabilitants already on long term sickness absence or even disability pensions [Citation15]. To evaluate the preventive effects of multimodal rehabilitation, future research should consider including participants with shorter period since pain onset. In one study of hospital employees, multimodal rehabilitation had no effects on future sickness absence when used on a group at risk of developing back pain [Citation29]. A paradoxical consequence of rehabilitation may be that persons who receive extensive interventions for their health problems may be perceived – and perceive themselves – as having more severe problems than persons who do not receive interventions. The result of this may be that these persons are forced into a “sick role” and that rehabilitation leads to the sickness absence that it was designed to prevent. This may be one explanation for the high proportion of participants in multimodal rehabilitation who were sick-listed after rehabilitation despite not having any registered sickness absence the year before the intervention started. However, the findings deviate from previous studies on the effect of multimodal rehabilitation, which have shown positive results on reduction of symptoms and improved disability after multimodal rehabilitation [Citation8,Citation10].

Sickness absence due to pain is a strong predictor of future disability pension [Citation30,Citation31] hence a positive effect of the rehabilitation guarantee was that multimodal rehabilitation significantly reduced the risk of being in receipt of a disability pension at follow-up. However, since disability pension is often the last resort after multiple treatment- and rehabilitation efforts, these results are not very surprising.

In conclusion, the national roll-out of multimodal rehabilitation did not fulfill the goal of reducing sickness absence. The assumption that rehabilitation does not affect sickness absence may, however, be over-hasty and may result in a so-called type-III error. The current study was carried out when the rehabilitation guarantee was being implemented, and it is known that implementation is a slow and unpredictable process [Citation32]. The implementation of the rehabilitation guarantee was a major challenge mainly for primary care, which became responsible for rehabilitating persons who were previously referred to specialized rehabilitation units. The implementation involved new working constellations and routines, going from individual work to multi-professional co-operation, competition with private actors, going from reducing symptoms and improving quality of life to rehabilitating with the primary goal of work return. Hence, the lack of result may also be due to how the rehabilitation was implemented in the county councils and at the health care units. Therefore, questions of program fidelity could not be addressed in the current study. However, a process evaluation of the rehabilitation guarantee indicates that few instructions about how to apply a vocational approach were offered to the health care units. Limited contacts between the rehabilitation setting and the work place, as well as a lack of guidelines and experience of vocational rehabilitation may partly explain why the sickness absence of rehabilitants was not reduced more rapidly [Citation15].

In addition, the return to work seems to be a complex and – in many cases – protracted process, in which persons may experience multiple shifts between work and different types of social benefit [Citation33]. It is therefore possible that our follow-up period of 12 months was too short to discern effects on sickness absence. This is in line with a qualitative study of the rehabilitation guarantee, in which multimodal rehabilitation teams were interviewed. In that study, return to work was perceived as a long-term process that was rarely planned to be accomplished within the period of the rehabilitation program. Moreover, the results of the study revealed that the rehabilitation staff did not perceive their role as being to facilitate a return to work but rather to facilitate health improvements. Their attitude could be described as “first health then work”, i.e., that work is not possible until a full recovery has been made. The study’s results demonstrate that these attitudes did in fact affect patients’ sick leave patterns [Citation34].

The timing of rehabilitation may be crucial for the outcome. According to our study, multimodal rehabilitation may not necessarily lead to reduced sickness absence, neither for persons with very long sickness absences nor for those without sickness absence. Most persons with back pain do eventually return to work; hence interventions may be most effective in preventing long-term sickness absence if they are given to those who have not returned to work after one month [Citation35].

Strengths and weaknesses

One of the major strengths of the current study was the use of national registers covering all individuals who started multimodal rehabilitation within the rehabilitation guarantee during the last quarter of 2009 and all quarters of 2010. The use of a matched control group made it possible to compare patterns of sickness absence in real life settings.

We used a matched-control design, which is an accepted and commonly-used design in observational studies. We obtained similar results with our complementary matching procedure, the coarsened exact matching algorithm; hence our conclusions do not seem to be dependent on the choice of matching procedure. However, matching was not entirely unproblematic, especially as there were only a limited number of variables available in the registers employed. Consequently, only age, sex, medical diagnoses and rate of previous sickness absence could be used as matching variables. Sickness absence is a complex outcome, dependent on multifaceted factors related to the individual (e.g., socioeconomic status, education, psychosocial factors, expectations about return to work, or perceived severity of the musculoskeletal pain), employers and workplaces (e.g., profession, work environment, control, demand, and social support) as well as the surrounding society’s conditions for sickness absence. The study would therefore have benefitted from more variables to describe the possible effects of the intervention. Although the variables used are among the most important predictors of sickness absence the possibility that non-rehabilitants differed in some other important respects cannot be ruled out. With more variables available, more sophisticated matching alternatives, such as creating propensity scores to ascertain similarities between the groups, could have been carried out.

Despite sharing some major risk factors for disability, the reason why some individuals were granted interventions within the rehabilitation guarantee while others were not, remains unclear. The study lacks information regarding the selection of participants to multimodal rehabilitation, such as assessment and examination. The fact that the Swedish government allocated funding to the county councils for providing multimodal rehabilitation could have affected the selection of patients in the way that other persons were included than what was originally planned. To be included in the rehabilitation guarantee and receive multimodal rehabilitation, the rehabilitant should have nonspecific musculoskeletal pain for a minimum of three months, due to a pain-related diagnose. However, pain-related diagnoses are complex and it is a well-known problem that these diagnoses may differ between physicians [Citation36]. Cohort I was not included in the study, due to incomplete register data. Furthermore, no detailed data on how the rehabilitation was conducted could be obtained, hence crucial questions of fidelity and adaptation could not be addressed as part of the current study. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the study’s findings.

Conclusions

The national roll-out of the rehabilitation guarantee was carried out to reduce sickness absence and increase work return among the target group. The idea of work return as an integral part of the program remained during the implementation phases, although guidelines and information about how to work with this goal were unavailable. The lack of connection between the rehabilitation setting and the workplace may partly explain the difficulties of reducing sickness absence in the rehabilitation groups, which continued to have higher rates of total sickness absence than their matched controls throughout the follow-up period. In this study, we used a national sample of rehabilitants and studied the effects at a national level. However, the rehabilitations were spread across the country and may have varied substantially.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

This study was funded by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. The funder had no role in the design, collection and analysis of data or the writing of, or the decision to publish this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Datta S, et al. Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal pain. Pain Phys. 2009;12:E35–E70.

- Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Maher CG, et al. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ. 2003;327:323.

- da C Menezes Costa L, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184:E613–E624.

- Axen I, Leboeuf-Yde C. Trajectories of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:601–612.

- Turk DC, Wilson HD. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:88–95.

- Hasenbring MI, Chehadi O, Titze C, et al. Fear and anxiety in the transition from acute to chronic pain: there is evidence for endurance besides avoidance. Pain Manag. 2014;4:363–374.

- Lee H, Hubscher M, Moseley GL, et al. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain. 2015;156:988–997.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444.

- Stigmar KG, Petersson IF, Joud A, et al. Promoting work ability in a structured national rehabilitation program in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: outcomes and predictors in a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:57.

- Norlund A, Ropponen A, Alexanderson K. Multidisciplinary interventions: review of studies of return to work after rehabilitation for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:115–121.

- Busch H, Bodin L, Bergström G, et al. Patterns of sickness absence a decade after pain-related multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Pain. 2011;152:1727–1733.

- Lin C, Haas M, Maher C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:1024–1038.

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, et al. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD000335.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain in adults: early management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2009.

- Björk Brämberg E, Klinga C, Jensen I, et al. Implementation of evidence-based rehabilitation for non-specific back pain and common mental health problems: a process evaluation of a nationwide initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:79.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Busch H, Bonnevier H, Hagberg J, et al. En nationell utvärdering av rehabiliteringsgarantins effekter på sjukfrånvaro och hälsa. Stockholm: Enheten för interventions- och implementeringsforskning, Institutet för miljömedicin, Karolinska Institutet; 2011.

- Magnussen LH, Strand LI, Skouen JS, et al. Long-term follow-up of disability pensioners having musculoskeletal disorders. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:407.

- Lederer V, Rivard M, Mechakra-Tahiri SD. Gender differences in personal and work-related determinants of return-to-work following long-term disability: a 5-year cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22:522–531.

- Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:80–86.

- Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, et al. CEM: coarsened exact matching in Stata. Stata J. 2009;9:524–546.

- Iacus S, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal. 2012;20:1–24.

- Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, et al. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:607–621.

- Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A. Rehabilitation and work ability: a systematic literature review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:796–804.

- Williams RM, Westmorland MG, Lin CA, et al. Effectiveness of workplace rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of work-related low back pain: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:607–624.

- van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:19–39.

- Jensen IB, Busch H, Bodin L, et al. Cost effectiveness of two rehabilitation programmes for neck and back pain patients: a seven year follow-up. Pain. 2009;142:202–208.

- Hoefsmit N, Houkes I, Nijhuis FJ. Intervention characteristics that facilitate return to work after sickness absence: a systematic literature review. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22:462–477.

- Roussel NA, Kos D, Demeure I, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary program for the prevention of low back pain in hospital employees: a randomized controlled trial. BMR. 2015;28:539–549.

- Dorner TE, Alexanderson K, Svedberg P, et al. Sickness absence due to back pain or depressive episode and the risk of all-cause and diagnosis-specific disability pension: a Swedish cohort study of 4,823,069 individuals. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1308–1320.

- Jansson C, Alexanderson K. Sickness absence due to musculoskeletal diagnoses and risk of diagnosis-specific disability pension: a nationwide Swedish prospective cohort study. Pain. 2013;154:933–941.

- Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969–1975.

- Oyeflaten I, Lie SA, Ihlebaek CM, et al. Multiple transitions in sick leave, disability benefits, and return to work – a 4-year follow-up of patients participating in a work-related rehabilitation program. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:748.

- Hellman T, Jensen I, Bergstrom G, et al. Returning to work – a long-term process reaching beyond the time frames of multimodal non-specific back pain rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:499–505.

- Wynne-Jones G, Cowen J, Jordan JL, et al. Absence from work and return to work in people with back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:448–456.

- Mallen CD, Thomas E, Belcher J, et al. Point-of-care prognosis for common musculoskeletal pain in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1119–1125.