Abstract

Purpose: Map the literature about valued activities and informal caregiving post stroke and determine the nature, extent, and consequences of caregivers’ activity changes.

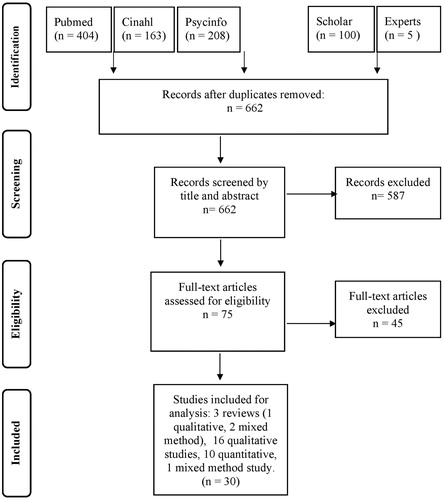

Methods: A scoping review was undertaken, searching Pubmed, Cinahl, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar. Two researchers independently identified relevant articles, extracted study characteristics and findings, and assigned codes describing the topics and outcomes. Using thematic analysis, the main study topics and study outcomes were described.

Results: The search yielded 662 studies, 30 of which were included. These were mainly qualitative and cross-sectional studies assessing caregivers’ activity changes and related factors, or exploring caregivers’ feelings, needs and strategies to deal with their activity challenges. Although caregivers often lost their social and leisure activities, which made them feel unhappy and socially isolated, we found no studies about professional interventions to help caregivers maintain their activities. Over the years, caregivers’ activity levels generally increased. However, some caregivers suffered from sustained activity loss, which, in turn, relates to depression.

Conclusion: Loss of valued activities is common for stroke caregivers. Although high-level evidence is lacking, our results suggest that sustained activity loss can cause stroke caregivers to experience poor mental health and wellbeing. Suggestions to help caregivers maintain their valued activities are presented.

Not only stroke survivors but also their informal caregivers tend to lose their valued activities, such as their social and leisure activities.

Although many caregivers manage to resume their valued activities over time, others suffer from sustained activity loss up to at least two years post stroke.

Loss of valued activities in stroke caregivers can result in lower levels of wellbeing, depression, and social isolation.

Rehabilitation professionals should screen stroke caregivers for activity loss and assist them in resuming their valued activities and maintaining their social contacts.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Providing informal care to a stroke survivor is often demanding [Citation1,Citation2]. Once the stroke survivor returns home from hospital or from the rehabilitation center, most caregivers have to provide extensive care and suddenly must perform activities that were previously done by the stroke survivor, such as household tasks or finances [Citation3–5]. The demands of caregiving can limit caregivers’ time for themselves and restrict participation in their own valued activities, such as work, leisure, or family life [Citation1,Citation6]. Caregivers’ loss of these activities is likely to be related to a decline in their health and wellbeing [Citation1,Citation2,Citation6]. So far, however, little is known about the nature, extent, and consequences of caregivers’ loss of valued activities [Citation6,Citation7]. In addition, review studies [Citation8,Citation9] show that caregiver interventions rarely address this loss. As a result, the best way to help caregivers maintain these activities, if necessary, remains unclear.

We undertook a scoping review to map the literature related to stroke caregivers’ valued activities, the consequences of changes in these activities, and possible strategies to help caregivers maintain them. Unlike systematic reviews that bring together evidence to answer a specific research question, scoping reviews have a broad “scope” with less restrictive inclusion criteria. They are conducted to determine what evidence is available on a specific topic and to represent this evidence by mapping or charting the data [Citation10]. Results from this particular scoping review may help define future research issues, support professionals in helping caregivers maintain their valued activities, and improve our understanding of how this can be done most effectively.

In the context of this review, valued activities were defined as activities that were voluntary chosen by caregivers and of specific value to them, for example, because they help caregivers regain the strength to combine their caregiving role with their family role or social position. Valued activities can be any kind of activity, such as playing a game, reading a book, practising a profession, or going on holiday. Although taking care for the stroke survivor can also be highly valued by informal caregivers, in the context of this review we did not consider this caretaking to be a valued activity [Citation11]. We argued that caregivers are often suddenly confronted with their new care task and, at least at first, this task is usually not chosen but required by circumstances. We also excluded instrumental activities such as “speaking” or “solving problems” from our definition because these activities were assumed to only be a precondition of caregivers’ valued activities.

Aim and review questions

The aim of this scoping review was to:

Conceptually map the literature according to the main study characteristics (year of publication, country, scientific area, study focus, participants, methods/methodology, methodological quality);

Identify existing knowledge related to caregivers’ valued activities post stroke and the consequences of caregivers’ activity changes (e.g., related to their health or wellbeing);

Identify strategies that professionals can use to help stroke caregivers maintain their valued activities;

Identify knowledge gaps and areas for further research.

Methods

Framework and search

We used the scoping review methodology frameworks of Arksey and O’Malley [Citation12] and Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien [Citation13] to conduct our scoping review. Arksey and O’Malley’s framework was developed to address existing knowledge about how to undertake scoping reviews [Citation12]. It was further refined by Levac et al., who enhanced the clarity and rigor of the scoping review process [Citation13].

We searched for literature in the following databases: Pubmed, Cinahl, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar. Our search period was May 2005 to May 2016, and we used the following search terms: stroke, caregiving or caregiver, family, spouse, meaningful activity, valued activity, role, occupation, and leisure time. We also consulted subject matter experts (occupational therapists, nurses, sociologists) for useful additional literature.

Inclusion of studies

We included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies that were written in English and addressed the valued activities of informal caregivers who provided care to community-dwelling stroke survivors on a daily to weekly basis. Two researchers (MW and SJ) independently identified the articles that met the inclusion criteria by title, abstract and full text. Prior to each inclusion step, they used a sample of ten reports to verify agreement in applying the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was solved by discussion. In cases where no consensus was reached, a third subject matter expert’s opinion (RS) was final.

Assessing methodological quality

We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) lists [Citation14] to assess the methodological quality of the studies. Each original study was independently assessed by RS or MW and SJ using the specific list per design (qualitative, cohort, or review study). Any disagreement was solved by discussion. Percentage scores of quality were calculated based on fulfilled items divided by the total number of relevant items. Studies with CASP scores ≤65% were considered to have poor methodological quality.

Data extraction

Extraction of the main study characteristics and study findings was done by two researchers (MW and SJ) independently. Findings related to stroke caregivers’ valued activities were extracted from all qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies by selecting those text passages and outcomes that were related to caregivers’ activities such as their work, leisure, or social activities. Subsequently, consensus was reached about exactly which passages and outcomes to extract.

Next, quantitative outcomes were transformed into qualitative findings by describing the essence of the outcomes in words. This transformation of quantitative outcomes is common in mixed-data reviews and is used so that quantitative and qualitative data can be combined and subjected to qualitative analysis [Citation15].

Finally, the researchers independently described the content of each finding briefly, while staying as close as possible to the original text and meaning. These brief descriptions of content can be referred to as “meaning units” [Citation16]. When researchers had different opinions about the transformation of quantitative data or the content of the meaning units, they discussed the full text to obtain agreement.

Analysis

One researcher (MW) made a descriptive numerical summary charting the main characteristics of the included studies. This was checked by the other researcher (SJ). Subsequently, a qualitative content analysis of all study findings was conducted. To identify the main topics described in the included studies, as well as to determine the main study findings, codes describing the topic and codes describing the content were assigned to all formulated meaning units. This was done by both researchers independently, reaching consensus afterwards. Then, through analyses of the codes, overarching categories of codes and emerging themes, the main topics and the main findings present in the identified studies were described. If a certain finding was exclusively derived from studies with poor methodology, it was marked as “methodologically poor”.

Subsequently, overall analyses allowed the researchers to describe the state of current knowledge related to valued activities and activity changes in stroke caregivers. Conclusions about missing research areas could then be drawn. Finally, as recommended by Levac et al. [Citation13], the preliminary findings were shared with stakeholders (stroke caregivers, nurses, allied health care professionals, sociologists) to identify additional emerging issues and validate findings and conclusions.

Results

As shown in , the search yielded 662 studies, 30 of which met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 16 were qualitative studies, 10 were quantitative studies, 1 was a mixed-method study, and 3 were reviews (one qualitative meta-synthesis, one mixed-method systematic review, and one comprehensive review of qualitative and quantitative data). Initially, our selection criteria had been very broad and included any scientific data related to stroke caregivers’ participation in valued activities. After having reviewed a sample of 50 abstracts from the original search strategy, we narrowed the criteria to data that were related to potentially observable valued activities. In the context of this review, “caregivers feeling tired because of all their old and new responsibilities” was therefore not extracted, while “caregivers feeling tired because they had to combine work, childcare, household, and stroke caregiving activities” was. We applied this criterion to all the search results.

Study characteristics

Almost all included studies were conducted in high-income Western countries such as Canada and Sweden. Three studies came from middle-income countries (India, Brazil, South Africa). The topic of valued activities was predominantly studied by researchers from occupational therapy science (14 studies) and nursing science (11 studies). It was furthermore studied by researchers from psychology/psychiatry (6), neurology/neuroscience (6), physical therapy science (2), and language & communication sciences (1). We found eight studies that aimed to identify experiences of stroke caregivers in general, nine that searched for factors relating to wellbeing or life satisfaction and ten that specifically researched valued activities of stroke caregivers and the factors associated with these activities. In addition, three studies investigated how caregivers responded to or dealt with alterations in their valued activities. We found no studies on professional interventions to help caregivers maintain their valued activities.

Participants were mainly women providing care to their spouses or parents. Five studies focused on caregivers younger than 66 years old, three on older caregivers, and twelve on both. In ten studies, the ages were not reported. Overall, the reported mean age of the caregivers ranged from 46 to 64 years (ages ranged from 16 to 86). Measurement time-points of the qualitative data were several days to 18 years post stroke; time-points of the quantitative data were 1 month to 2 years post stroke.

The included qualitative studies mainly used semi-structured interviews to explore informal caregivers’ experiences. Some studies used a descriptive approach, while others used an interpretive approach to thematic analysis. The quantitative studies were all cross-sectional or cohort studies. They used a variety of measures, such as the Caregiver Impact Scale (CIS) [Citation17], the Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS) [Citation18], the Life Satisfaction Checklist (LiSat-9) [Citation19], the Occupational Gaps Questionnaire (OGQ) [Citation20], or the Activity Card Sort (ACS) [Citation21]. Of these measures, only the OGQ and the ACS completely consist of questions about daily activities. The other measures are multicomponent scales from which we only extracted the data about valued activities. The one mixed-method study combined the ACS with open-ended questions. shows all the study characteristics as well as the methods of data collection/analyses as described by the authors.

Table 1. Studies and their characteristics.

Table 1. Continued.

Table 1. Continued.

Findings (methodologically poor studies are marked with * , [Citation22–24] are reviews)

Thematic analyses of all study findings revealed that six main topics were described in the included studies. These topics and the related main study findings were as follows:

Activity changes

The studies that described stroke caregivers’ activity changes found that caregivers often immediately put aside their own needs and quit many of the activities they had valued before so they could concentrate on the stroke survivor [Citation25–32]. Although social and leisure activities were the most frequently abandoned [Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation28], activity loss was also reported in work [Citation27,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34], cultural and recreational activities [Citation26,Citation35], exercise [Citation31,Citation33], shopping, household and cooking [Citation26,Citation36], sexual activities [Citation37,Citation38], outside activities [Citation26,Citation33,Citation36,Citation39], and traveling [Citation31,Citation35]. Young caregivers reported that caregiving interfered with their family activities and child-rearing tasks [Citation31,Citation34,Citation39]. As time went by, most caregivers gradually developed new routines, dared to leave the stroke survivor alone more often and were able to resume some of their former activities [Citation32,Citation39,Citation40]. This was confirmed by quantitative studies that found that caregivers’ activity levels generally improved with time [Citation29].

In some cases, caregivers reported no activity loss at all [Citation25,Citation26,Citation41] or even reported that family activities had increased as a result of the stroke [Citation36].

Reasons for activity changes

Several studies described why activities had changed as a result of the caregiving. Some caregivers explained that their activity loss had to do with the inability to do things as a “couple unit” [Citation42]. For example, the stroke survivor’s physical limitations could make activities outside the house difficult [Citation26,Citation30] and, as a result, both the caregiver’s and the stroke survivor’s activities decreased [Citation30,Citation36,Citation43]. Caregivers often hesitated to engage in activities that were previously done together, because they found it no fun to do them alone or felt guilty because the stroke survivor was not able to go with them [Citation35].

For other caregivers, activity loss had to do with the inability to leave the stroke survivor alone, which prevented them from doing things on their own [Citation22,Citation26,Citation32]. Caregivers who were the spouse or partner of the stroke survivor often experienced a self-imposed sense of responsibility and reconciled themselves to the idea that staying at home was in the best interest of the stroke survivor. They did not want to ask for help from others and, even if there was help from a home healthcare service, they had trouble leaving the stroke survivor [Citation39]. When they did go out, they rushed through their errands and telephoned home frequently because they worried about the stroke survivor’s safety [Citation44].

Sometimes caregivers had no options for relief because their social network was limited or unhelpful [Citation31]. All the responsibilities and tasks then fell to them and, as a result, they only had the energy and time to do the most crucial things [Citation31,Citation35,Citation45]. They often had to reduce working hours or quit their job [Citation27,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34] which affected their income and, as a result, limited their activity choices [Citation26].

Relationship between valued activities and wellbeing or health

The qualitative studies that examined the impact of caregivers’ valued activities on their wellbeing or health described how the loss of valued activities negatively affected the caregivers’ wellbeing. However, if caregivers had the opportunity to do activities that were meaningful to them, their wellbeing and emotional vitality were enhanced [Citation32,Citation33,Citation39,Citation42]. In this respect, although combining work and caregiving was challenging, work was seen as an important activity because it provided caregivers with a source of personal space, enjoyment and a set timeframe for a break from caregiving [Citation32,Citation39]. It also seemed to help stroke survivors to develop their independence [Citation32], which ultimately made caregiving tasks easier.

Also seen as beneficial for the caregiver, as well as for the stroke survivor and the family, was doing things together. When families managed to engage in mutual activities, this often led to a new sense of closeness and wellbeing, which helped the family move on. However, a decline in mutual activities or an asymmetry in activities (the caregiver or family being occupied and the stroke survivor being inactive) often affected the relationship [Citation30,Citation32,Citation40].

According to the quantitative studies in this review, caregivers’ higher activity levels were indeed significantly associated with higher levels of positive affect [Citation46], vitality and general mental health [Citation25], and lower levels of role strain* [Citation28], burden [Citation25,Citation41] and depression [Citation29,Citation47]. However, caregivers who worked were slightly more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than non-working caregivers [Citation27]. Two studies examined the connection between activity levels and physical health, but they found no significant relationship [Citation25,Citation29].

Most of the included quantitative studies did not explicitly differentiate between short-term and long-term caregiving or only researched caregivers during the first year post stroke, so they provided little insight into how long-term activity loss relates to wellbeing. One of the few studies that followed the caregivers up to 2 years post stroke found that, although caregivers’ activity levels tend to increase with time [Citation29], on average across the whole sample, the levels of positive affect remained stable during these first 2 years. Also, unlike the first year post stroke, after 2 years, lower activity levels were no longer significantly associated with lower levels of positive affect [Citation46]. However, 2 years out, two other studies found activity loss to still be significantly associated with caregivers’ depressive symptoms [Citation29,Citation47].

Caregivers’ feelings, needs and wishes regarding activity changes

The studies that examined the caregivers’ feelings, needs, and wishes reported that, especially in the early period after discharge, caregivers felt that they were “not having a life of their own” and “not being the person they were before”. They missed “breathing space” and felt like “a prisoner in their own house” [Citation32,Citation34,Citation36,Citation45]. Especially when caregivers had little support, had to combine many tasks and were compelled to choose between different roles (i.e., being a partner and caregiver), they felt overwhelmed and experienced sorrow and blame for not having enough strength to do everything [Citation31]. Respite that allowed them to focus on their own activities and needs, even for a few hours, was seen as critical to continuing the caregiving role [Citation22,Citation44,Citation45].

Many caregivers also felt isolated [Citation44,Citation48] due to their reduced social life and related loss of social contacts [Citation36,Citation39,Citation44,Citation48,Citation49]. They needed people who could safely care for the stroke survivor so they could meet up with friends or enjoy some activities of their own, such as going to the gym, gardening or reading a book [Citation35,Citation42].

As time went by, caregivers gradually felt calmer and experienced a sense of freedom and more joy in their activities [Citation30,Citation32,Citation39]. Caregivers who were able to maintain their previous activities despite their caregiving task described these activities as more purposeful than before [Citation35].

Dealing with activity changes

The studies that examined how caregivers dealt with their activity changes noted that, particularly in the early phase after discharge, caregivers worked hard to support the stroke survivor and the family while trying to keep their heads above water. They learned not to reflect on their own circumstances too much and just carried on [Citation26,Citation39]. However, with time, they became more concerned about their own needs [Citation30] and began a process of reprioritizing their activities and better dealing with their activity challenges [Citation32]. They had to accept that certain personal and mutual activities could not be resumed. However, they also realized that at least some activities were important to maintain despite the great upheaval in daily life (e.g., a yearly camping trip). They made sacrifices but, by being creative, they also developed new valued activities or resumed the same ones by adapting them to the new circumstances [Citation30,Citation32]. They also negotiated with the stroke survivor and other family members regarding the use of shared and separate time, and mutual and individual activities [Citation30], and learned to ask for help* [Citation50]. When caregivers had to give up their jobs, they found it helpful to replace the missing “breathing space” gained from work with joyful activities, such as listening to music [Citation32].

Who is especially “at risk” for activity loss

Several qualitative and quantitative studies reported that some caregivers were more at risk for activity loss than others. They described how caregivers who took care of their spouse or partner were more likely to suffer from activity loss than other family members/friends [Citation29,Citation30]. Also, younger caregivers [Citation29,Citation38], caregivers who remained employed [Citation26,Citation29,Citation33], provided higher levels of assistance [Citation29] or provided care to stroke survivors with poorer physical or cognitive functioning, poorer community participation or little progress [Citation29,Citation32,Citation41,Citation43,Citation49], resumed their valued activities less often. However, one study found no association between stroke severity and caregivers’ activity restriction* [Citation51]. Regarding the caregiver’s gender, the findings were also inconsistent: One study found gender to be unrelated to caregivers’ activity changes [Citation29], while another study found the decline in social activities to be more profound in men* [Citation51].

Because most of the above studies either took their measurements only shortly after stroke (up to 6 months) or did not differentiate between short-term and long-term caregiving at all, the findings of this review gave little insight into which caregivers are especially at risk for long-term activity loss. However, one quantitative study that did investigate relatively long-term caregiving, found that caregivers who were younger, provided higher levels of assistance and provided care to stroke survivors with lower levels of community participation, were significantly more likely to suffer from activity loss at 2 years post stroke [Citation29]. Specific data on risk factors present at later points in time were not available.

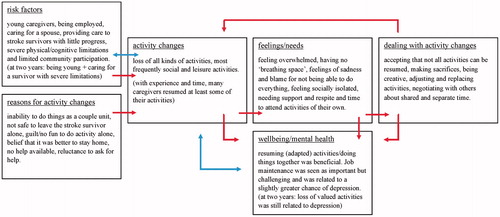

Connections between the topics found

gives a brief overview of the six topics mentioned above as well as the main findings per topic. It also displays the connections between these topics as described within the different studies (the red arrows represent the reported causal relationship as described within the qualitative data; the blue arrows describe the found associations as based on the correlations present within the quantitative data).

Figure 2. Overview of the topics and main findings present in the included studies. Arrows indicate the causal relationships as suggested or described in the studies (red: reported causal relationship found in the qualitative data;blue: associations found based on correlations in the quantitative data).

Discussion

This scoping review identified a range of studies about valued activities and caregiving post stroke. Although all these studies investigated different aspects of this concept and we found no controlled trials that clarified how stroke caregiving, activity loss and wellbeing precisely influence each other, qualitative studies gave some insight into how they may be related. Together, findings indicate that, at least in the first period after the stroke, caregiving often results in a decline in valued activities which can lead to social isolation and poor mental health and wellbeing. If, in this case, caregivers either are supported by others to continue their activities, or are able to accept their situation and adapt their activities to the new circumstances, their activity levels generally increase and their wellbeing is enhanced. However, in some specific cases (such as in young caregivers or in case of stroke survivors with severe limitations) caregivers tend to suffer from sustained activity loss, which, in turn, is related to higher levels of depression.

The findings of this review are in accordance with findings from other studies, (e.g., related to dementia and elderly care), which show that informal caregiving indeed results in a loss of social and leisure activities, which, in turn, can increase caregivers’ levels of stress and depression [Citation52–54]. However, increased participation in social activities, sports, music, or religious activities was shown to reduce depressive symptoms in these caregivers [Citation53,Citation54], as well as in older people in general [Citation55].

Because several studies found that engagement in activities can protect against the negative effects of caregiving and improve caregivers’ mental health, it seems important that professionals screen stroke caregivers for activity loss and, if necessary, help them resume their activities. Also, activity engagement should be incorporated into existing caregiving interventions as a default part of caregiver education [Citation53,Citation54]. However, as shown in this review, the available literature offers little insight into what strategies are effective in helping caregivers maintain their valued activities. Moreover, the literature did not clarify how exactly these activities can contribute to a satisfying social life and mental health and wellbeing. It also did not clarify which activities are especially vital for caregivers to maintain, or at what point it is better to reprioritise and let go of some activities to avoid exhaustion.

Therefore, before adequate strategies to help caregivers maintain their valued activities can be developed, there needs to be a better understanding of how valued activities relate to wellbeing. The “loss of self” frequently mentioned by caregivers who report no opportunities to engage in the activities they value most [Citation45,Citation56] may explain why their wellbeing is often affected. Because a person’s activities and social connections in daily life seem to be highly related to his or her feelings of identity [Citation57,Citation58] and maintaining an acceptable sense of identity is essential to wellbeing [Citation58–60], identity theory may be helpful in further clarifying the relationship between caregiving, valued activities and wellbeing. Furthermore, theory about balance of activities in daily life [Citation61] could help explain what mix of different activities (and rest) seems to be ideal in particular cases.

What can be done to help now?

The findings of this review suggest that, although we lack a thorough insight into the precise benefit of activity maintenance and what exactly helps caregivers maintain their activities, at least something can be done to improve caregivers’ wellbeing and prevent their social isolation and depression. Based on the findings of this review, it seems important that health professionals explain to caregivers the benefits of taking time for themselves and maintaining some activities and interests of their own. Especially in the first phase post stroke, when caregivers often forget about their own needs, professionals should help caregivers become aware of their activity priorities and support them in finding practical solutions to maintain these activities.

Furthermore, professionals could support caregivers in their negotiations with others to allow them some time away from the stroke survivor. When activity loss is unavoidable, professionals can help caregivers adapt to their new reality and seek out alternative activities that suit their needs. Also, since doing things together can be beneficial to both the caregiver and the stroke survivor, professionals could help find ways to undertake these mutual activities and arrange some assistance if necessary.

Social support is essential to the caregivers’ ability to manage their situation after discharge [Citation62]. However, in contrast to what caregivers often expect, help from others is often limited and tends to decline over time [Citation62–64]. Therefore, professionals should inform caregivers that it is important for them to maintain their social network so that they will have the opportunity to ask for help and maintain their social activities, which these caregivers often value highly.

Because work can be an important part of the caregiver’s identity, a stable source of social contact and a welcome distraction from caregiving, it seems important that professionals also help caregivers maintain their jobs. However, although work provides caregivers with the necessary income and subsequent activity opportunities, combining work with caregiving can also be highly demanding and the advantages will not always outweigh the disadvantages. In this respect, one study [Citation65] found that, among women taking care of a stroke survivor living in their own household, engagement in a full-time job was related to better psychological wellbeing. However, another study [Citation66] found that combining caregiving with work outside the house had no positive effect on caregivers’ stress levels, except when they cared for a person with a mental disability. Therefore, because work is beneficial for some caregivers and not for others, professionals should be cautious when offering advice on whether caregivers should attempt to maintain their jobs.

Future research

Future research should attempt to clarify the relationship between stroke caregiving, valued activities, identity and related factors such as mental health and wellbeing. In particular, there is a need for quantitative research into long-time caregiving, related activity changes and mental health or wellbeing.

As was shown in this review, many studies only measure activity loss as a part of bigger constructs, such as “caregiver burden”. However, future research that aims to specifically identify and understand caregivers’ activity loss should use instruments that specifically measure this loss (e.g., ACS, OGQ). Subsequently, interventions that have the potential to enhance the valued activities of caregivers who are vulnerable for activity loss and mental health problems, such as depression, should be developed and tested for their effectiveness.

As the studies in this review mainly included female caregivers, future research should also address male caregivers and their activities so that future interventions can be tailored if necessary. Furthermore, it seems useful to study the activities and experiences of caregivers from non-Western backgrounds. As one’s identity is shaped by social and cultural norms [Citation67,Citation68], comparing the experiences of caregivers from Western and non-Western countries could add to our knowledge of how specific valued activities, in specific social circumstances, relate to a person’s identity and wellbeing.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strength of this study was the extensive overview of knowledge available about valued activities and caregiving post stroke. This topic is highly relevant to stroke rehabilitation policies, but has not been given much attention in the scientific literature until now. Because many scoping reviews do not sufficiently operationalize the method of synthesis used [Citation69], we made efforts to clarify and describe our data synthesis method as precisely as possible. We also assessed the methodological quality of the included studies and marked the low methodological quality findings. However, as is common in scoping reviews, we did not adjust our findings based on their methodological quality.

In general, we found few studies that explicitly aimed to examine the relationship between stroke caregiving and activity changes. To be able to at least give a first overview of what is known in the field, we also had to extract findings from studies that only tenuously examined this topic. Although, as a result, the literature we found described various subjects and participants and used different methods and measures, most findings indicated that stroke caregiving results in a loss of caregivers’ valued activities, which, in turn, affects caregivers’ mental health or wellbeing. However, there are no controlled trial studies available, so there is no quantitative evidence that confirms the causal relationships between these topics.

Moreover, as the included studies varied widely with regards to the cultural context or time of measurement after stroke, it is not yet clear in what cases exactly what findings are valid. As a result, conclusions drawn in this study can be seen as global. Nevertheless, this review gives a good first impression of issues related to activities valued by stroke caregivers.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Greenwood N, Mackenzie A. Informal caring for stroke survivors: meta-ethnographic review of qualitative literature. Maturitas. 2010;66:268–276.

- Camak DJ. Addressing the burden of stroke caregivers: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2376–2382.

- Bakas T, Austin JK, Jessup SL, et al. Time and difficulty of tasks provided by family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:95–106.

- Coombs UE. Spousal caregiving for stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:112–119.

- Perry L, Middleton S. An investigation of family carers’ needs following stroke survivors’ discharge from acute hospital care in Australia. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1890–1900.

- Peyrovi H, Mohammad-Saeid D, Farahani-Nia M, et al. The relationship between perceived life changes and depression in caregivers of stroke patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44:329–336.

- Visser-Meily A, Post M, Gorter JW, et al. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1557–1561.

- Corry M, While A, Neenan K, et al. A systematic review of systematic reviews on interventions for caregivers of people with chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:718–734.

- Bakas T, Clark P, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions. Stroke. 2014;45:1–17.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2015 edition/supplement. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015.

- Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1413–1422.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Meth. 2005;8:19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

- CASP UK, CASP checklists, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Oxford; 2013. [cited 2015 Jun]; Available from: http://www.casp-uk.net/

- Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch. 2006;13:1–15.

- Timulak L, Creaner M. Experiences of conducting qualitative meta-analysis. Couns Psychol Rev. 2013;28:94–104.

- Cameron JI, Franche RL, Cheung AM, et al. Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer. 2002;94:521–527.

- Elmstahl S, Malmberg B, Annerstedt L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:177–182.

- Fugl-Meyer AR, Branholm IB, Fugl-Meyer KS. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northers Swedes. Clin Rehabil. 1991;5:25–33.

- Eriksson G, Tham K, Kottorp A. A cross-diagnostic validation of an instrument measuring participation in everyday occupations: the Occupational Gaps Questionnaire (OGQ). Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:152–160.

- Baum CM, Edwards D. Activity Card Sort. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press; 2008.

- Quinn K, Murray C, Malone C. Spousal experiences of coping with and adapting to caregiving for a partner who has a stroke: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:185–198.

- Pellerin C, Rochette A, Racine E. Social participation of relatives post-stroke: the role of rehabilitation and related ethical issues. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1055–1064.

- McGurk R, Kneebone II. The problems faced by informal carers to people with aphasia after stroke: a literature review. Aphasiology. 2013;27:765–783.

- Kniepmann K. Female family carers for survivors of stroke: occupational loss and quality of life. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75:208–216.

- Kniepmann K, Cupler MH. Occupational changes in caregivers for spouses with stroke and aphasia. Br J Occup Ther. 2014;77:10–18.

- Ko JY, Aycock DM, Clark PC. A comparison of working versus nonworking family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:217–225.

- Oliveira AR, Rodrigues R, de Sousa VE, et al. Clinical indicators of 'caregiver role strain' in caregivers of stroke patients. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44:215–224.

- Grigorovich A, Forde S, Levinson D, et al. Restricted participation in stroke caregivers: who is at risk? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1284–1290.

- Arntzen C, Hamran T. Stroke survivors’ and relatives’ negotiation of relational and activity changes: a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23:39–49.

- Bastawrous M, Gignac MA, Kapral MK, et al. Adult daughters providing post-stroke care to a parent: a qualitative study of the impact that role overload has on lifestyle, participation and family relationships. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:592–600.

- Van Dongen I, Josephsson S, Ekstam L. Changes in daily occupations and the meaning of work for three women caring for relatives post-stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:348–358.

- Barbic SP, Mayo NE, White CL, et al. Emotional vitality in family caregivers: Content validation of a theoretical framework. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2865–2872.

- Thomas M, Greenop K. Caregiver experiences and perceptions of stroke. Health SA Gesondheid. 2008;13:29–40.

- Cao V, Chung C, Ferreira A, et al. Changes in activities of wives caring for their husbands following stroke. Physiother Can. 2010;62:35–43.

- Green TL, King KM. Experiences of male patients and wife-caregivers in the first year post-discharge following minor stroke: a descriptive qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1194–1200.

- Carlsson GE, Forsberg-Warleby G, Moller A, et al. Comparison of life satisfaction within couples one year after a partner’s stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:219–224.

- Tellier M, Rochette A, Lefebvre H. Impact of mild stroke on the quality of life of spouses. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011;34:209–214.

- Backstrom B, Sundin K. The experience of being a middle-aged close relative of a person who has suffered a stroke–six months after discharge from a rehabilitation clinic. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24:116–124.

- Pierce LL, Steiner V, Govoni AL, et al. Two sides to the caregiving story. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14:13–20.

- Kniepmann K. Family caregiving for husbands with stroke: an occupational perspective on leisure in the stress process. OTJR. 2014;34:131–140.

- Winkler M, Bedford V, Northcott S, et al. Aphasia blog talk: how does stroke and aphasia affect the carer and their relationship with the person with aphasia? Aphasiology. 2014;28:1301–1319.

- Vincent C, Desrosiers J, Landreville P, et al. Burden of caregivers of people with stroke: evolution and predictors. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:456–464.

- White CL, Korner-Bitensky N, Rodrigue N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to caring for individuals with stroke in the community: the family’s experience. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;29:5–12.

- Pierce LL, Thompson TL, Govoni AL, et al. Caregivers’ incongruence: emotional strain in caring for persons with stroke. Rehabil Nurs. 2012;37:258–266.

- Cameron JI, Stewart DE, Streiner DL, et al. What makes family caregivers happy during the first 2 years post stroke? Stroke. 2014;45:1084–1089.

- Cameron JI, Cheung AM, Streiner DL, et al. Stroke survivor depressive symptoms are associated with family caregiver depression during the first 2 years poststroke. Stroke. 2011;42:302–306.

- Brittain KR, Shaw C. The social consequences of living with and dealing with incontinence – a carers perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1274–1283.

- Laliberte Rudman D, Hebert D, Reid D. Living in a restricted occupational world: the occupational experiences of stroke survivors who are wheelchair users and their caregivers. Can J Occup Ther. 2005;73:141–152.

- Pierce LL, Steiner V, Smelser J. Stroke caregivers share ABCs of caring. Rehabil Nurs. 2009;34:200–208.

- Sreedharan SE, Unnikrishnan JP, Amal MG, et al. Employment status, social function decline and caregiver burden among stroke survivors. A South Indian study. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:97–101.

- Loucks A, Kleiber DA, Williamson GM. Activity restriction and well-being in middle-aged and older caregivers. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2006;22:269–282.

- Schuz B, Czerniawski A, Davie N, et al. Leisure time activities and mental health in informal dementia caregivers. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2015;7:230–248.

- Wakui T, Saito T, Agree EM, et al. Effects of home, outside leisure, social, and peer activity on psychological health among Japanese family caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16:500–506.

- Forsman AK, Schierenbeck I, Wahlbeck K. Psychosocial interventions for the prevention of depression in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Health. 2011;23:387–416.

- Buschenfeld K, Morris R, Lockwood S. The experience of partners of young stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1643–1651.

- Burke PJ, Stets JE. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 2000;63:224–237.

- Gallagher M, Muldoon OT, Pettigrew J. An integrative review of social and occupational factors influencing health and wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1281–1292.

- Savundranayagam MY, Montgomery RJV. Impact of role discrepancies on caregiver burden among spouses. Res Aging. 2009;32:175–199.

- Haslam C, Holme A, Haslam SA, et al. Maintaining group memberships: social identity continuity predicts well-being after stroke. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18:671–691.

- Dur M, Steiner G, Fialka-Moser V, et al. Development of a new occupational balance questionnaire: incorporating the perspectives of patients and healthy people in the design of a self-reported occupational balance outcome instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:1–11.

- White CL, Brady TL, Saucedo LL, et al. Towards a better understanding of readmissions after stroke: partnering with stroke survivors and caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1091–1100.

- Adriaansen JJ, van Leeuwen CM, Visser-Meily JM, et al. Course of social support and relationships between social support and life satisfaction in spouses of patients with stroke in the chronic phase. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:48–52.

- Simon C, Kumar S, Kendrick T. Cohort study of informal carers of first-time stroke survivors: profile of health and social changes in the first year of caregiving. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:404–410.

- Hansen T, Slagsvold B. Feeling the squeeze? The effects of combining work and informal caregiving on psychological well-being. Eur J Ageing. 2015;12:51–60.

- Bainbridge HT, Cregan C, Kulik CT. The effect of multiple roles on caregiver stress outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:490–497.

- Baumeister RF. Self and identity: a brief overview of what they are, what they do, and how they work. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1234:48–55.

- Phelan S, Kinsella EA. Occupational identity: engaging socio-cultural perspectives. J Occup Sci. 2009;16:85–91.

- Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Antony J, et al. A scoping review identifies multiple emerging knowledge synthesis methods, but few studies operationalize the method. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:19–28.