Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to identify and report demographic data of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss, assess participation in audiological rehabilitation and analyze the benefits of various rehabilitation methods.

Materials and methods: Data on 4286 patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairments registered in the Swedish Quality Register of Otorhinolaryngology over a period from 2006–2015 were studied. Demographic data, gender differences, audiological rehabilitation and benefits of the rehabilitation were analyzed.

Results: Group rehabilitation and visits to a hearing rehabilitation educator provided the most benefits in audiological rehabilitation. Only 40.5% of the patients received extended audiological rehabilitation, of which 54.5% were women. A total of 9.5% of patients participated in group rehabilitation, with 59.5% being women. Women also visited technicians, welfare officers, hearing rehabilitation educators, psychologists and physicians and received communication rehabilitation in a group and fit with cochlea implants significantly more often than did men.

Conclusions: The study emphasizes the importance of being given the opportunity to participate in group rehabilitation and meet a hearing rehabilitation educator to experience the benefits of hearing rehabilitation. There is a need to offer extended audiological rehabilitation, especially in terms of gender differences, to provide the same impact for women and men.

Significantly more women than men with severe-to-profound hearing impairment receive audiological rehabilitation.

Hearing impairment appears to have a significantly more negative impact on women’s quality of life than men’s.

It is important to offer extended audiological rehabilitation to all patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss to obtain an equal hearing health care regardless of gender.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Hearing impairment affects communication [Citation1] and reduces the participation and inclusion in society on several levels. The consequences of hearing impairment can include social isolation [Citation2], daily life activity limitations [Citation3], well-being effects, and higher levels of anxiety and depression [Citation4].

Hearing impairment can be mild (26–40 dB HL), moderate (41–70 dB HL), severe (71–90 dB HL), or profound (more than 91 dB HL) measured at four frequencies (500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz), defined as the pure-tone average of hearing loss (PTA4) [Citation5]. Patients belonging to the severe-to-profound hearing impairment group are defined as having a 70 decibel hearing level (dB HL) or more in the best ear [Citation6]. The estimated prevalence in Sweden of severe-to-profound hearing impairment is 0.2% of the population [Citation7], which is similar to the United States [Citation8] but contrasts with the 0.7% in the United Kingdom [Citation9].

Depending on the degree of hearing loss, patient’s needs and other disabilities, an individualized care plan is made, and various types of audiological rehabilitative services are offered to the patient. Establishment of a care plan is recommended, but there are variations in how it is used in Sweden. These include technical rehabilitation with hearing devices and extended audiological rehabilitation. The common definition of extended audiological rehabilitation implies that a patient has participated in a group rehabilitation or been rehabilitated at least by three different specialists in hearing health care, such as physicians, psychologists, hearing rehabilitation educators, welfare officers, technicians and audiologists [Citation10].

Technical rehabilitation includes hearing aids, cochlear implants (CI) and other technical aids such as t-loops and FM-systems. The binaural fitting of hearing aids improves listening in noise [Citation11], and the use of the aids for many hours per day influences a more positive satisfaction with the rehabilitation [Citation12]. Auditory training/rehabilitation by hearing aids/CI improves cognitive functions such as short-term memory as well as reducing social isolation and symptoms of depression [Citation13]. However, patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss needs more than technical rehabilitation with hearing aids and/or CI.

Patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss should be automatically included in an interdisciplinary extended audiological rehabilitation program containing medical, psychological, social and educational content [Citation14]. Backenroth and Ahlner [Citation15] emphasizes the importance of audiological rehabilitation to increase the awareness of the hearing impairment and its impact on daily life. Participation in audiological group rehabilitation seems to have a significant positive effect on patients’ quality-of-life (QoL) [Citation16]. To improve communication strategies for patients with hearing loss, the use of Active Communication Education program is suggested [Citation17].

Equal health care and treatment regardless of age, gender and disability [Citation18] needs to be highlighted more in the area of audiological rehabilitation. It is important that patients are involved in their own rehabilitation and health care, and the goal for audiological rehabilitation is to implement a patient-centered approach [Citation19]. To avoid poor health and social isolation, hearing health care has an important role in the hearing-impaired person’s life to supply support and effective tools for communication. In Sweden, the organization for audiological rehabilitation differs between county councils and regions. There are three different types of hearing health care providers: traditional “public” hearing health care, authorized “private but publicly funded” and “completely private” units [Citation20].

In Sweden, a national quality registry for severe-to-profound hearing loss in adults was established in 2005. This registry monitor rehabilitation efforts in hearing health care and assumes be fairly representative of the total population of this patient group in Sweden. The quality register contains data from a general questionnaire and a health questionnaire including the EuroQoL-5D-3L (EQ5D). The general questionnaire contains audiometric data and queries about heredity and demographic information. The health questionnaire (EQ5D) includes questions about health status. The EQ5D also contains the Problems Impact Rating Scale (PIRS) [Citation21], a quality of life (QoL) instrument measuring the effects of hearing impairment on daily life.

By use of the above registry, the overall aim of the present study was to identify and characterize patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss who participated in audiological rehabilitation. One major purpose was also to examine gender equality in Swedish hearing health care for this patient group. Furthermore, we investigated in detail which kind of rehabilitation this patient group had received, and particularly the benefits of hearing health care and effects on quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study population

The register study is based on data from 4286 patients registered in the national quality register for severe-to-profound hearing impairment in adults in Sweden between 2006 and December 2015 (https://orl.registercentrum.se/).

Inclusion criteria for the quality register for patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss

The inclusion criteria are adult patients, ≥19 years old, with average hearing thresholds at four frequencies (500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz) of 70 dB HL or more in the best ear. Patients are also included in the register if their speech recognition test score in the better ear is worse than 50%.

Measurements

The quality register contains a general questionnaire and a health questionnaire (EQ5D) including the Problems Impact Rating Scale (PIRS) (Supplementary Table S1). The general questionnaire includes hearing impairment values and questions about heredity and demographic characteristics, such as marital status and education level, employment, sick leave/sickness, chronic diseases, communication problems, and other disabilities. The general questionnaire also describes the use of sign language and/or tactile language, and if the patients need to have a writing interpreter. It includes questions about hearing aids/CIs use, participation in audiological rehabilitation and benefits of rehabilitation. An analysis of all of the visits that patients participated in was completed to determine whether patients received extended audiological rehabilitation, that is, if patient had visited at least three specialists or had participated in group rehabilitation.

The health questionnaire (EQ5D) is a standardized instrument that measures various aspects of health status. The EQ5D includes questions about mobility, hygiene, daily activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression, and support from family and work as well as the benefit of audiological interventions. A value <0.7 represents a negative impact on QoL [Citation22].

The self-rating instrument was the Problems Impact Rating Scale (PIRS), which measures the impact of hearing impairment on daily life. The PIRS scale ranges from 0–100, and a score ≥70 has been defined as a strong negative impact on daily life [Citation21].

Audiological rehabilitation

Definitions

Audiological rehabilitation involves various professionals such as audiologists, hearing rehabilitation educators, welfare officers, psychologists, physicians, and technicians. To say that a patient has participated in group rehabilitation, the patient must have been taught in a group by several hearing care professionals.

Communication rehabilitation in a group can involve learning, for example, sign language, sign support language, training for lip-reading or hearing tactics. The classification for extended audiological rehabilitation is that the patient has participated in group rehabilitation or that the patient has received hearing rehabilitation from at least three different occupational professions (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed with the IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 24. The data from the general questionnaire and the QoL parameters were analyzed using unpaired t-tests, and the categorical data were analyzed using chi-square tests. The mean, median, standard deviations and percentages were used. There were some missing data because some participants had not answered all the questions, that is, regarding some demographic characteristics, diagnoses for hearing impairment, type of communication, use of hearing aids and CI, EQ5D and PIRS.

For logistic regression analyses, Hosmer and Lemeshow Test was used to determine the correct method of analysis. In the analyses of the benefit of audiological rehabilitation efforts small groups, such as speech therapists and physiotherapists, were excluded. The benefit of each specific rehabilitation effort was calculated using crude OR. Several patients had received many different rehabilitation efforts and therefore adjusted OR were used including all efforts given to each patient.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was issued by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm (2014/2101–31).

Results

Demographic data

The demographic data were collected from 18 of 21 county councils in Sweden (Supplementary Table S3), and the degree of coverage varied by county councils/regions (from 23 to 1183 registrations), with no relation to their varying populations. Four county councils/regions, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, both of which hold the largest cities in Sweden, as well as Värmland and Örebro (two regions with mid-sized towns), accounted for 66% of registrations, whereas the remaining 14 county councils/regions accounted for 34% (Supplementary Figure S1).

The demographic characteristics of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss and results of statistical comparisons between genders are shown in . The number of men (n = 2157) and women (n = 2129) were similar. The mean age of the population of 4286 patients was 69 years (SD 17.3), and 2696 (63%) responders were >65 years of age. There were no significant gender differences regarding age. Of the total population, 2134 (50.2%) lived alone, with a significantly higher proportion of those living alone being women (57%). The highest education level attained for 1666 individuals (39%) was elementary school; 1231 (29%) reached upper secondary school/middle school; 245 (5.5%) attended “folk high school”Footnote1; 663 (15.5%) attended college/university; and 464 (11%) received other types of education. The latter represented various types of training schools, such as hairdresser, mechanic, pastry chef, chef, cutlery, furniture maker, car mechanic, and industrial school. There were no significant differences between genders regarding education level, with the exception of significantly more women than men receiving a folk high school education, 7% and 4.5%, respectively. Of the 4286 patients, 854 (20.5%) were diagnosed with hearing impairment before the age of three, and no significant gender differences were found in this young population.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics in patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss in Sweden with the proportions of male and female patients, crude odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing gender differences.

Of 4207 patient responses, most (94%) used speech for communication. Sign language was used by 531 (13%), sign support language by 260 (6.5%), tactile language by 26 (1%) and support with written language interpreters by 485 (42% of 1152) of the patients. One person might use several of these languages. A gender difference was found for the use of sign support language with significantly more women (59.5%) using that type of language than men ().

Diagnoses for hearing impairment

Of the participants, 1143 (27.5%) had a specific disease diagnosis for the cause of their hearing impairment, such as genetics (12.5%), Ménière’s disease (3%), otosclerosis (5%), chronic otitis (3.5%), meningitis (2%), ototoxicity (0.5%), or rubella (1%), while another portion of the participants, that is, 795 (18.5%), had been diagnosed with other causes, such as noise damage, trauma, other inflammations or a tumor. The remaining 2203 (51.5%) patients had an unknown cause of hearing impairmentFootnote2.

Gender distribution of diagnoses for patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss indicate that genetic diseases (58%**) and otosclerosis (67%***) were significantly more common in female patients than in male patients.

Hearing thresholds

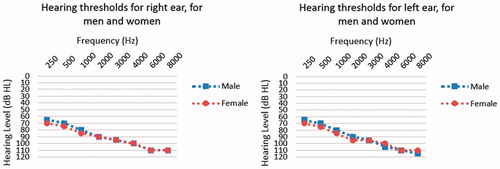

The median air-conduction hearing thresholds for patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss (n = 4286) showed 5 dB HL poorer hearing thresholds for females at frequencies 250–2000 for left ear and 250–1000 Hz for right ear. Males had poorer hearing thresholds on the left ear at 4 kHz and 8 kHz ().

Audiological rehabilitation

shows the number of patients who received various types of audiological rehabilitation. A total of 1734 (40.5%) patients received extended audiological rehabilitation. Of these 946 (54.5%) were female patients, which was a significantly higher proportion than men. Four-hundred and eleven patients (9.5%) received group rehabilitationFootnote3. Almost all patients, 4175 (97.5%), met with an audiologist. A significantly higher proportion of women received group rehabilitation, communication rehabilitation in a groupFootnote4, and extended audiological rehabilitation, and/or visits to a technician, welfare officer, hearing rehabilitation educator, psychologist or physician more often than men.

Table 2. The proportion of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss in audiological rehabilitation with various hearing care professionals in Sweden with the proportions of male and female patients, crude odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing gender differences.

Benefits of hearing health care efforts, various audiological rehabilitation efforts and hearing aids/CI

Benefit of hearing health care efforts

Our results indicate that 3223 (88%) of 3661Footnote5 patients received “good/very good” benefit of audiological rehabilitation in general. A total of 12% experienced none/some benefit. Only 109 (3%) had no benefit. We observed no gender differences for the benefits of hearing health care efforts.

Benefit of various audiological rehabilitation efforts

shows the benefit of being rehabilitated with various types of professionals with multiple competencies. The table shows the proportion of patients with none/only some benefit from the various rehabilitation forms. The rest of the patients experienced good/very good benefit from the rehabilitation. We observed that group rehabilitation, visits to a hearing rehabilitation educator, psychologist, and physician, and communication rehabilitation in a group were important aspects when experiencing benefit from audiological rehabilitation according to the crude OR analysis.

Table 3. The benefit of various audiological rehabilitation efforts for patients who participated/not participated for group rehabilitation and/or visits to the multiple professional competencies, calculated with “None/Some” benefits, for patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment in Sweden, logistic regression analyses with crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For logistic regression Hosmer and Lemeshow Test shows goodness-of-fit 0.315.

However, for the adjusted OR, group rehabilitation and visits to a hearing rehabilitation educator were the two most central significant measures in experiencing the benefits of rehabilitation.

Benefit of extended audiological rehabilitation efforts

We found significantly fewer patients that experienced none/some benefit in those who participated (10.5%*) in extended audiological rehabilitation than in those who did not participate (13%). This finding also applies to patients with CIs.

Patients with CIs had a statistically significant difference in the benefit of the audiological rehabilitation given before and after the operation. Significantly fewer patients with CIs experienced none/some benefit (7%**) from the rehabilitation compared to patients who were not participated (12.5%) with CIs.

Hearing aids/cochlear implants (CIs)

Of the total 4286 patients, 1323 (31%) had a unilateral hearing aid either on the right or left ear, and only 2403 (58.5%) had bilateral hearing aidsFootnote6. The total number of participants with either unilateral or bilateral hearing aids was 3726 (87%).

Of all patients in the register, 400 (9.5%) had a unilateral CI either on the right or left ear. A total of 12 (0.5%) were fit with bilateral CIs.

Significantly more females (53.5%**) were fit with unilateral hearing aids. We observed a male dominance in hearing aid users, both for the total amount and the bilateral use of hearing aids. In contrast, there are statistically significant more female (58.5%***) users of CI than males.

EQ5D and PIRS – evaluation of health status and effect of hearing loss on daily life

The impact of hearing impairment on different aspects of patients’ health and the impact of hearing impairment on their daily life according to EQ5D and PIRS parameters are shown in . In the entire population of 3778 answers, we observed 1033 (27.5%) patients who had an EQ5D score of less than 0.7, which indicates a negative impact on quality of life. A total of 1440 (39.5%) of 3623 patients showed a PIRS score of ≥70, which indicates a strong negative impact on daily life. Hearing situations for female patients appeared to have a statistically significant negative impact on daily life, as evaluated by the PIRS score (53%), as well as lead to increased problems with aspects of their health status, as seen in the EQ5D (56.5%).

Table 4. The proportion of patients for different QoL outcomes, in patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss in Sweden with the proportions of male and female patients, Crude odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing gender differences.

Discussion

Group rehabilitation, extended audiological rehabilitation, and hearing rehabilitation educator visits and being fit with a CI were the most important efforts to experience benefits of the rehabilitation process for patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment in this study.

Only 4 of 10 patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss received extended audiological rehabilitation. Significantly more women than men received extended audiological rehabilitation, group rehabilitation and communications rehabilitation in group and had visited a technician, welfare officer, hearing rehabilitation educator, psychologist and physician.

Our findings also demonstrate that a hearing impairment had a more negative impact on women’s lives than men’s. Female patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss were slightly younger (mean age) and lived alone more often than male patients. Significantly more women than men were fit with a CI and with a unilateral hearing aid. Despite this, there were no significant differences between women and men in terms of the benefit of the audiological rehabilitation.

The study population

The female patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss were slightly younger (mean age) than men. The study found that 20.5% of patients were diagnosed for hearing loss before three years of age. There were significantly more females (57%) than men living alone. Similarly, a Norwegian study [Citation23] on the consequences of hearing loss in older adults had more single women (65.4%) than men. In this study, 39% of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss had elementary school as their highest education level, and only 15.5% had an education from a college or university. There were significantly more women than men with a folk high-school education, which coincides with the population in general in Sweden, which is 6 out of 10 [Citation24].

Most of the participants (94%) used spoken language. Thirteen percent used sign language, and almost seven percent used sign support language as their major form of communication. Our results revealed several women used sign language and significantly more women, 59.5%, used sign support language. One cannot emphasize enough the importance of everyone’s equal possibility within social interactions to avoid communication barriers in healthcare for patients who need other kinds of communication methods than speech [Citation25]. A US study [Citation26] demonstrated the awareness for equal health care for sign language users through more efficient communication without language barriers using professional sign language interpreters.

Limitations of the study

The present study covered 4286 adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss, registered in the Swedish quality register. Unfortunately, the coverage of all county councils/regions is not complete, with a variation of 23–1183 registrations [Citation7]. A limitation in the study is that the registry contains only approximately 4000 of the estimated 20,000 patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment in Sweden [Citation7].

Various professionals are invited to register patients in the quality registry, but registration is not compulsory. Most of the registrations are made by audiologists, hearing rehabilitation educators and physicians, followed by welfare officers, which can influence the sample of patients. Similarly, in relation to the total number of patients with a CI, the material is limited in terms of CI use, because many patients are not included in the registry.

Audiological rehabilitation

This study describes gender differences in regard to various rehabilitation activities and finds that women receive more benefits than do men. All audiological rehabilitation forms showed better participation by women than by men. One can speculate on the causes of help-seeking differences between genders. Women may have more demands on their social life and thus seek more help for their hearing impairment. It may also be related to the negative social stigma of hearing loss, which may affect men more than women. A US study reported more social participation for women and negative social interactions associated with younger age, living alone, and communication difficulties [Citation27]. In the present study, 57% of women were living alone, which may be one reason that makes women more eager to participate in different rehabilitation forms. Nearly everyone, 97.5%, met with an audiologist, and their role is important in this context. One possible explanation could be that male patients are more satisfied after visiting an audiologist and do not seek additional rehabilitation.

In contrast, in a US study [Citation28] there were more male patients, veterans, in all treatment groups. They found the largest effect on the hearing loss-related quality-of-life for a group that received informational lectures with psychosocial exercises and for a group with communications strategies with psychosocial exercises compared to a group that received only communications strategies. Boothroyd [Citation29] stressed the importance of managing hearing loss with instructions and training in using hearing aids and with the benefit of group counseling. The clinicians need to be reminded of patient-centered focus and gender perspectives when we interact with patients. Laplante-Lévesque et al. [Citation30] emphasized the importance of patient-centred hearing rehabilitation conducted in four countries, Denmark, UK, USA and Australia, to encourage better communication between patients and specialists.

Benefits of hearing health care efforts, various audiological rehabilitation efforts and hearing aids/CI

Benefit of hearing health care efforts

In general, more than 8 out of 10 patients were satisfied with the rehabilitation they received. The study showed that gender differences did not influence the satisfaction of patients regarding the type of hearing health care they received. Hearing loss and decreased health status created more difficulties in and limitations on elderly patients’ daily lives, but Solheim et al. [Citation23] found no gender impact on activity limitations and participation.

Benefit of various audiological rehabilitation efforts

In this study, we wanted to identify patients who experienced none or only some benefit from the audiological rehabilitation offered. Our results indicated that it is important to consider whether or not patient participations in group rehabilitation or communication rehabilitation in groups as well as visits with a hearing rehabilitation educator, psychologist, physician influenced their experience of none/some benefit from the rehabilitation received (Table 5). Our study showed statistically significant positive effects of participating in group rehabilitation and visiting a hearing rehabilitation educator, with an adjusted OR of 2.9 and 1.5, respectively. Similarly, using a program for communications strategies in a group, Öberg, Bohn and Larsson [Citation17] found improved psychosocial health status for patients with severe hearing loss. Interestingly, we found that the kind of rehabilitation efforts patients received, was of great importance to satisfaction, regardless of gender.

Benefit of extended audiological rehabilitation effort

The study indicated the importance of received audiological rehabilitation through group rehabilitation or visits with at least three different professionals to create a significantly greater chance of feeling satisfied with rehabilitation. The same applies to patients rehabilitated with a CI. Similarly, a Swedish study [Citation15] noted the importance of audiological rehabilitation, for example, using group rehabilitation, to increase knowledge of hearing loss and how it affects daily life. In addition, several studies have shown that a CI provides improved quality of life, as in a France study, where patients showed better communication abilities, QoL and autonomy [Citation31]. Similarly, a multinational longitudinal study showed significant improvements in QoL and hearing [Citation32] after receiving a CI.

All patients treated with a CI receive, by definition, extended rehabilitation with at least three different specialists involved in rehabilitation, and the results show that comprehensive rehabilitation efforts including advanced technical rehabilitation positively affect the patient's perception of and satisfaction with rehabilitation.

EQ5D and PIRS – evaluation of health status and effect of hearing loss on daily life

The standardized validated instruments EQ5D and PIRS were used in the study. Women with STPHL showed a more negative effect on QoL parameters than did men. The crude OR for PIRS suggested that compared to men, women with severe-to-profound hearing loss experienced a 1.2 times greater negative impact of hearing impairment on their daily life. In a recent study, Turunen-Taheri et al. [Citation33] found even greater negative effects with both crude and adjusted OR, with a 2.3 times greater negative impact on QoL (mean score 0.6) and 1.8 times greater negative impact on PIRS (mean score 62) for patients with severe vision impairments combined with severe-to-profound hearing loss, than the control group with severe-to-profound hearing impairment only.

Diagnoses for hearing impairment

The analysis showed that 46% of the study population had a known cause of hearing impairment, such as genetic factors, Ménière’s disease, otosclerosis, chronic otitis, meningitis, ototoxicity and rubella or other diagnoses such as noise damage, trauma, tumor, or infections. Significantly more women than men were diagnosed with a genetic cause or otosclerosis. The latter coincides with previous studies showing women more commonly suffering from otosclerosis [Citation34]. Increased age affects hearing [Citation35], and 73% of patients in the study were over 60 years old. It is well-known that environmental impacts, such as noise exposure, cause hearing loss [Citation36].

Hearing thresholds

We found 5 dB HL poorer hearing thresholds (PTA thresholds at 250–2000 Hz for the left ear and at 250–1000 Hz for the right ear) for women than for men, which was similar to findings reported by Narne et al. [Citation37]. Our study showed that hearing thresholds for only 4000 and 8000 Hz in the left ear were 5 dB HL poorer for men than for women, but no differences were found for the right ear. In contrast Pearson et al. [Citation38] found that women had better thresholds above 1000 Hz.

In a US [Citation38] and a Finnish study [Citation39], men showed significantly poorer hearing thresholds, especially at higher frequencies. This is probably due to noise causes, as men often work in noisy industries, and many studies, specifically a Swedish study, show that the left ear is more damaged at these frequencies [Citation40]. One can assume that the reason why our study did not show major gender differences in hearing levels is that the entire population has a severe-to-profound hearing loss. Wiley et al. [Citation41] reported the generally greatest threshold changes for lower frequencies in older age groups (70–89 years), while for younger age groups (50–60 years), changes were greater for higher frequencies. They also found that men generally had worse hearing at the 4 and 6 kHz frequencies, but women showed increased hearing loss for these frequencies for age groups 48–69 years, and afterwards, these changes tended to level out.

Hearing aids/CIs

In this study, a total of 3726 patients had hearing aids, either on the right, left ear or bilaterally. Six of 10 patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss had bilateral hearing aids, and only 0.5% had bilateral CIs. Interestingly, there were more men than women with hearing aids, and significantly more women were fit with a unilateral hearing aid only. In contrast, significantly more woman than men were fit with a CI. Kaplan-Neeman et al. [Citation12] had more male patients with hearing aids in their study, similar to Naylor et al. [Citation42]. A binaural fitting and a longer time per day of use was related to higher satisfaction with hearing aids in the Kaplan-Neeman study [Citation12].

Conclusions

Even though nearly 9 out of 10 patients were satisfied with the rehabilitation they were offered, patients who participated in group rehabilitation and/or visited a hearing rehabilitation educator were more satisfied with their audiological rehabilitation. A total of 40.5% of patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss received extended audiological rehabilitation. In the present study, significantly more women than men participated in various types of audiological rehabilitation such as group rehabilitation, communication rehabilitation in groups, and visits with a technician, welfare officer, hearing rehabilitation educator, psychologist and physician. Women were fit more often with cochlear implants than were men. The results of the present study indicate that it is important to offer extended audiological rehabilitation, especially on terms that all patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss to receive equal hearing health care.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (450.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Upper secondary school level, a Nordic school form for adult education, sometimes known as boarding-school, in Swedish called “Folk high school” or Residential College for Education.

2 Missing data of 28 answers.

3 Group rehabilitation: having attended rehabilitation in a group with various hearing care professionals.

4 Communication rehabilitation in a group: e.g., sign language, sign support language, lip-read training, hearing tactics.

5 Missing data from 625 answers.

6 560 (13%) had no hearing aids.

References

- Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, et al. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43:661–668.

- Ramage-Morin PL. Hearing difficulties and feelings of social isolation among canadians aged 45 or older. Health Rep. 2016;27:3–12.

- Helvik AS, Jacobsen G, Wennberg S, et al. Activity limitation and participation restriction in adults seeking hearing aid fitting and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:281–288.

- Bernabei V, Morini V, Moretti F, et al. Vision and hearing impairments are associated with depressive-anxiety syndrome in Italian elderly. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:467–474.

- Clark JG. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. Asha. 1981;23:493–500.

- Martini A. Definitions, protocols and guidelines in genetic hearing impairment. London: Whurr; 2001.

- Swedish quality register of otorhinolaryngology; 2017. [cited 2017 May 2] Available from: www.entqualitysweden.se

- Blanchfield BB, Feldman JJ, Dunbar JL, et al. The severely to profoundly hearing-impaired population in the united states: prevalence estimates and demographics. J Am Acad Audiol. 2001;12:183–189.

- Turton L, Smith P. Prevalence & characteristics of severe and profound hearing loss in adults in a uk national health service clinic. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:92–97.

- Carlsson P-I. National quality registry for severe hearing loss in adults. Svensk ÖNH-Tidskrift. 2012;19:8–10.

- Arlinger S, Gatehouse S, Kiessling J, et al. The design of a project to assess bilateral versus unilateral hearing aid fitting. Trends Amplif. 2008;12:137–144.

- Kaplan-Neeman R, Muchnik C, Hildesheimer M, et al. Hearing aid satisfaction and use in the advanced digital era. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2029–2036.

- Castiglione A, Benatti A, Velardita C, et al. Aging, cognitive decline and hearing loss: effects of auditory rehabilitation and training with hearing aids and cochlear implants on cognitive function and depression among older adults. Audiol Neurotol. 2016;21(Suppl 1):21–28.

- Ringdahl A, Grimby A. Severe-profound hearing impairment and health-related quality of life among post-lingual deafened Swedish adults. Scand Audiol. 2000;29:266–275.

- Backenroth GA, Ahlner BH. Hearing loss in working life-some aspects of audiological rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res. 1998;21:331–333.

- Preminger JE, Meeks S. Evaluation of an audiological rehabilitation program for spouses of people with hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21:315–328.

- Oberg M, Bohn T, Larsson U. Short- and long-term effects of the modified swedish version of the active communication education (ace) program for adults with hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014;25:848–858.

- Socialstyrelsen. Den jämlika vårdens väntrum-läget nu och vägen framåt. Handbook 2011.

- Grenness C, Hickson L, Laplante-Levesque A, et al. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2014;53(Suppl 1):S68–S75.

- Brannstrom KJ, Basjo S, Larsson J, et al. Psychosocial work environment among swedish audiologists. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:151–161.

- Carlsson PI, Hall M, Lind KJ, et al. Quality of life, psychosocial consequences, and audiological rehabilitation after sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2011;50:139–144.

- Carlsson PI, Hjaldahl J, Magnuson A, et al. Severe to profound hearing impairment: quality of life, psychosocial consequences and audiological rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:1849–1856.

- Solheim J, Kvaerner KJ, Falkenberg ES. Daily life consequences of hearing loss in the elderly. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:2179–2185.

- Statistiska centralbyrån. Level of education for population; 2015. [cited 2017 Sep 27] Available from: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Folkhogskolan-en-vag-till-hogre-studier/

- Dickson M, Magowan R, Magowan R. Meeting deaf patients' communication needs. Nurs Times. 2014;110:12–15.

- Pendergrass KM, Nemeth L, Newman SD, et al. Nurse practitioner perceptions of barriers and facilitators in providing health care for deaf american sign language users: a qualitative socio-ecological approach. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:316–323.

- Palmer AD, Newsom JT, Rook KS. How does difficulty communicating affect the social relationships of older adults? An exploration using data from a national survey. J Commun Disord. 2016;62:131–146.

- Preminger JE, Yoo JK. Do group audiologic rehabilitation activities influence psychosocial outcomes?. Am J Audiol. 2010;19:109–125.

- Boothroyd A. Adult aural rehabilitation: what is it and does it work?. Trends Amplif. 2007;11:63–71.

- Laplante-Levesque A, Knudsen LV, Preminger JE, et al. Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. Int J Audiol. 2012;51:93–102.

- Sonnet MH, Montaut-Verient B, Niemier JY, et al. Cognitive abilities and quality of life after cochlear implantation in the elderly. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:e296–e301.

- Lenarz T, Muller L, Czerniejewska-Wolska H, et al. Patient-related benefits for adults with cochlear implantation: a multicultural longitudinal observational study. Audiol Neurotol. 2017;22:61–73.

- Turunen-Taheri S, Skagerstrand A, Hellstrom S, et al. Patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment and simultaneous severe vision impairment: a quality-of-life study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:279–285.

- Redfors YD, Moller C. Otosclerosis: thirty-year follow-up after surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:608–614.

- Gates GA, Mills JH. Presbycusis. Lancet. 2005;366:1111–1120.

- Bovo R, Ciorba A, Martini A. Environmental and genetic factors in age-related hearing impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;23:3–10.

- Narne VK, Prabhu P, Chandan HS, et al. Gender differences in audiological findings and hearing aid benefit in 255 individuals with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016;27:839–845.

- Pearson JD, Morrell CH, Gordon-Salant S, et al. Gender differences in a longitudinal study of age-associated hearing loss. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97:1196–1205.

- Hannula S, Maki-Torkko E, Majamaa K, et al. Hearing in a 54- to 66-year-old population in northern finland. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:920–927.

- Carlsson P, Borg E, Grip L, et al. Variability in noise susceptibility in a swedish population: the role of 35delg mutation in the connexin 26 (gjb2) gene. Audiological Medicine. 2004;2:123–130.

- Wiley TL, Chappell R, Carmichael L, et al. Changes in hearing thresholds over 10 years in older adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19:281–292. quiz 371.

- Naylor G, Oberg M, Wanstrom G, et al. Exploring the effects of the narrative embodied in the hearing aid fitting process on treatment outcomes. Ear Hear. 2015;36:517–526.