Abstract

Purpose: This study aims to increase our understanding of employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities. Despite employers’ significant role in labor market inclusion for people with disabilities, research is scarce on how employers view employability for this group.

Methods: This was a qualitative empirical study with a phenomenographic approach using semi-structured interviews with 27 Swedish employers from a variety of settings and with varied experience of working with people with disabilities.

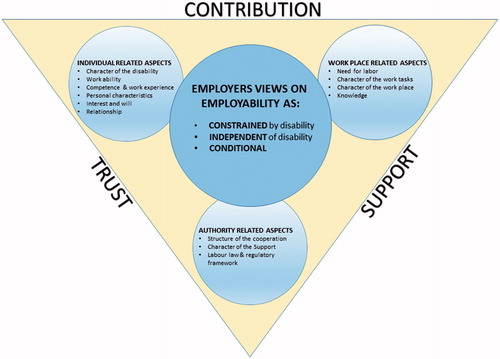

Results: The characteristics of employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities can be described as multifaceted. Different understandings of the interplay between underlying individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects form three qualitatively different views of employability, namely as constrained by disability, independent of disability, and conditional. These views are also characterized on a meta-level through their association with the cross-cutting themes: trust, contribution, and support.

Conclusions: The study presents a framework for understanding employers’ different views of employability for people with disabilities as a complex internal relationship between conceived individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects. Knowledge of the variation in conceptions of employability for people with disability may facilitate for rehabilitation professionals to tailor their support for building trustful partnerships with employers, which may enhance the inclusion of people with disabilities on the labor market.

Employers’ views on employing people with disabilities vary with respect to individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects in relation to trust, contribution and support.

Knowledge of the employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities can support professionals in authorities and in vocational rehabilitation.

The findings illustrate the importance of analyzing what type of support employers need as a starting point for building trustful partnerships between authority actors and employers.

The findings offer a vocabulary that can be used by professionals in authorities and in vocational rehabilitation in tailoring employer-oriented support to increase labor market inclusion of people with disabilities.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Labor market participation varies among different societal groups, and people with disabilities stand out as having especially low labor market representation. Work participation among this group is lower than for people without disabilities, both in Sweden [Citation1] and internationally [Citation2]. Apart from causing economic and social disparities for these individuals, the high unemployment rate of people with disabilities is also related to societal costs associated with being excluded from the labor market. Swedish policies for labor market integration involve a strong work principle, where several authorities are involved in helping individuals to achieve employment. Municipalities generally have labor market departments where social workers promote work training or subsidized employment. Furthermore, the Public Employment Services, a national authority, is commissioned to support the unemployed in job-matching and may also supply vocational rehabilitation measures to individuals with more complex needs.

The employment situation for people with disabilities highlights the need to explore factors contributing to their low labor market inclusion, with the aim of increasing employment equality. Since employers play a significant role in the process of employment, it is crucial to investigate their perspective, especially their views on the employability of people with disabilities. Reviews of previous research within the field give a heterogeneous picture with contrasting results of employers’ views of labor market inclusion for people with disabilities. These reviews also show that studies have a tendency to dichotomize, categorize, and oversimplify employers’ attitudes as either being negative or positive [Citation3–5].

Studies that support the assumption that employers have a negative approach toward hiring people with disabilities focus on several different impeding factors. Employers’ pervasive negative views about the work productivity of people with disabilities are mentioned in several studies, along with employers’ lack of knowledge concerning disabilities and accommodation strategies [Citation5–7]. Other studies have described the character of the disability as a constraining factor for employment, where psychiatric disabilities in particular are emphasized as aggravating employability [Citation4,Citation5,Citation8]. Concerns about costs related to hiring people with disabilities are another factor seen as a barrier to labor market inclusion [Citation6,Citation9,Citation10]. Lack of integrated services and accessible resources and lack of established partnerships between authority actors and employers are also mentioned as impeding factors [Citation5].

Other studies present contrasting findings, indicating that employers are positive toward hiring people with disabilities. One factor that has been connected to favorable attitudes toward labor market inclusion is employers’ previous experiences of working with people with disabilities [Citation4,Citation8,Citation9]. Other studies have described employers as having positive attitudes toward certain types of disabilities, including psychiatric and intellectual disabilities [Citation4]. Factors related to the perceived benefits of hiring people with disabilities were high attendance and long tenure [Citation9,Citation11], and financial support from authorities [Citation12,Citation13]. Several studies have also emphasized the importance of consultation and assistance from disability employment services as facilitating factors [Citation3,Citation10,Citation14].

This variation in employers’ views concerning disability and employability have been explained by a diversity in study settings, methods, concepts, and samples of employers and workplaces, which make it difficult to compare results and draw conclusions [Citation3]. A discrepancy between studies presenting employers as willing to hire people with disabilities and their actual hiring process has also been pointed out, where the employment rate is still low and continues to decline. This discrepancy was identified by Greenwood and Johnson as early as 1987 [Citation15] and has been identified in several other studies since [Citation5,Citation8,Citation9,Citation16]. Kaye et al. [Citation10] argue that these studies have biased results due to employer self-selection and social desirability yielding non-representative or artificially positive conclusions.

These variations in previous research indicate that studies need to account for the different factors that may influence employers into taking different views on people with disability. Research needs to map the perceptions of employers from varied contexts and with varied experiences of working with people with disabilities, in order to understand the nuances of and the interplay between factors impacting decisions relating to hiring people with disabilities. It is therefore relevant to focus on the variation in employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities, how these variations can be understood, and what their distinctive features are.

Aim

The purpose of the study is to increase the understanding of the views of employers regarding the employability of people with disabilities by mapping employers’ different perceptions of disability and employability and the aspects that build up their views.

Methods

This is a qualitative empirical study with a phenomenographic approach. Phenomenography is the empirical study of the qualitatively different ways in which people understand various phenomena in the world around them and how these ways of understanding are related to one another [Citation17,Citation18]. The main result of a phenomenographic analysis is the outcome space, comprising a set of descriptive categories that display the variation in how the conceptions are structured through their internal relationship [Citation18]. In this study, a phenomenographic approach was used to map the qualitatively different ways in which employers understand the phenomenon of employability of people with disabilities.

Sample

An interview study was conducted with 27 employer representatives in a region in Sweden. The interviewees consisted of 18 women and nine men. Their job titles were chief executive officer, manager, and human resource manager or consultant. In phenomenography, as in many other qualitative research approaches, the sampling is not representative, but strategic [Citation20]. Strategic sampling was used to maximize variation in the choice of interviewees in order to capture the possible ways the phenomenon is understood across different professional areas, in private and public sectors, and in companies of different sizes. Moreover, employers were selected based on their varied experience of working with disabled people. The first 16 of the 27 interviewees were recruited from a local CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) network. All of them had an interest in labor market inclusion issues but differed in their experience of internship, handling and hiring of people with disabilities. To increase variation in the sample, the remaining 11 interviewees were recruited to complement the different professional fields in the first interviews, and in particular to add variation regarding experience and perceptions of labor market inclusion and collaboration with authorities. The majority of these companies did not have any pronounced social responsibility obligations, but had experience of both internship and hiring people with disabilities. Moreover, several of these employers had resigned from previous collaboration with the authorities around people with disabilities due to dissatisfaction, and some of the employers had no experience in hiring or working with people with disabilities. This variation was an important aspect of the sampling in order to avoid bias due to employer self-selection and social desirability. A list of employer characteristics can be found in .

Table 1: Employer demographic characteristics.

Data collection

Data collection was performed through qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted by one of the authors from August 2015 to April 2016. A semi-structured interview guide was used with questions concerning the employers’ experience and their views of the employability of people with disabilities. The employers were asked to describe their company and characteristics of their workplace and tasks, need for labor, recruiting routines, views on CSR, work ability and employability of people with disabilities, and factors influencing their will and ability to initiate or increase collaboration with authorities concerning hiring people with disabilities. Employers with experience of working with people with disabilities were asked to describe the individuals and the setup of the internship or subsidized employment, and the perceived facilitative or obstructive factors for employability in order to find out how these experiences had affected their views.

The interviews lasted for an hour on average, with a range of 45 to 90 min. All interviews were carried out at each employer’s workplace with the exception of one, which was conducted in a neutral office environment. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The phenomenographic analysis was performed in accordance with the procedure described by Sjöström and Dahlgren [Citation19]. The analysis procedure consists of seven steps and is described in .

Table 2. The phenomenographic analysis procedure.

Results

Based on the employers’ responses to the interview questions, three categories portraying different views of the employability of people with disabilities emerged: 1. Employability as constrained by disability, 2) Employability as independent of disability, and 3) Employability as conditional. These categories are described from several aspects, relating to individuals, the workplace, and authorities, which in varying ways promote or obstruct and build up the three different views. An overview of these descriptive results and related quotes is presented in .

Table 3. Overview of the categories and selected quotes.

Employability as constrained by disability

The statements in this category were characterized by the perception that people with disabilities lacked the competence, work experience, and personal characteristics sought after and required for the task. Also, the character of the disability was perceived to constrain employability. A typical view was the perception that people with disabilities were unreliable labor due to frequent absences. Another view was that people with disabilities (particularly those with psychiatric disabilities) were difficult to include in the workplace since their reduced work ability meant that they could not perform tasks like employees without disabilities, and instead they imposed high demands on the employer concerning adaptations and flexibility. Furthermore, people with disabilities were seen as lacking both interest in the professional field and a willingness to work, which had a negative impact on their employability.

Workplace-related aspects in this category concerned the workplaces’ need for labor and the view of people with disabilities as not being applicable to the employers’ demands for labor. The employers’ need for a work force was related to the character of the tasks and a typical view was that reduced work capacity could not be compensated by adaptations or support. The view of disability constraining employability was also related to the character of the workplace. High work load and low access to support from human resources were related to perceptions of working with people as time-, energy-, and resource-demanding. Furthermore, lack of knowledge about disabilities and customizations were aspects mentioned, which constrained employability, particularly at workplaces with limited experience of workplace inclusion and where the management did not prioritize taking a social responsibility.

Employability of people with disability could also be constrained as a consequence of suboptimal contacts with authorities, more specifically concerning the structure of the cooperation. A typical view was that cooperation between the employer and the authorities with regard to employees with disabilities lacked continuity and structure and that it was commonly seen as designed to suit the authorities and the disabled person rather than the employer. Other aspects concerned the character of support available to employers, with lacking personal support for employees with such needs. Not having a specific contact person who was accessible and reliable was also mentioned as a constraint; further, the financial support offered by the employment service was perceived to be insufficient, since it did not fully compensate for the reduction in work capacity. Moreover, the administration around this financial support was considered complicated and time-consuming. Labor laws and the regulatory framework were seen as obstructing cooperation and inclusion, contributing to the opinion that employing people with disabilities was demanding and difficult.

Employability as independent of disability

Typical of the view of employability as independent of disability was that individual-related aspects such as having the right competence and experience, characteristics, a strong will to work, and an interest in the professional field were more important factors for employability than a person’s disability. Disability was not seen as directly affecting work ability and thereby was not considered to affect the person’s employability. In some contexts, disability could even be seen as a resource, where certain characteristics were attributed to specific disabilities. For example, creativity and high energy levels were associated with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and orderliness was considered as a typical characteristic for people with Asperger’s syndrome.

Workplace-related aspects of employability as independent of disability were related to the employers’ need for labor. A typical view was that a need for labor and difficulties in finding it increased the incentive to focus on abilities rather than disabilities, and to view people with disabilities as a resource that added value for the employers. This view was related to the characteristics of the tasks, and that employees with disabilities had the capacity to perform them just as well as employees without disabilities, depending on the degree of qualification. The character of the workplace, and the workplace culture were perceived to have importance for employability; typical of this view was the perception that employees with disabilities were contributive and added value to the workplace, despite their disabilities.

According to this view, authorities were not considered to have much importance in determining whether or not employers would hire a person with a disability. The structure of the cooperation mattered little, as authorities did not have a central role in connecting the employer and employee or organizing the internship or employment. Authority support was perceived as facilitating employment but was not seen as a prerequisite.

Employability as conditional

Typical of the view of employability as conditional was the perception that employability was not predetermined by the disability, but influenced by different individual-, workplace- and authority-related aspects and their interaction. The different aspects could be both hampering and promoting, depending on the interplay between them, and the context. Individual-related aspects were seen as something that can be influenced and must be understood in relation to a specific job, rather than in a general sense. The statements relate the employability to the character of disability and the work ability, where physical, mental and social limitations had different influences in different work contexts. Other individual-related aspects influencing employability were competence and experience, personal characteristics, interest in the professional area, and willingness to work in relation to specific jobs. An additional aspect was the employers’ relationship to the employee, where having knowledge about the person and the disability, directly or through a mediator, was perceived to facilitate employability.

Work-related aspects concerned the importance of identifying the employers’ need for labor and clarifying whether there is a need for a position within the core business, or an additional position that has been created and subsidized. For positions within the core business, the employment for employees with disabilities was perceived to depend on how well the employee lived up to the employers’ demands and requirement profile. For created positions, demands on productivity were lower and there was a greater acceptance of limitations and reduced work capacity. Created positions and internships were seen as taking social responsibility and could be seen as adding value to the workplace by increasing knowledge and acceptance for diversity and different work abilities/work disabilities. However, employers’ need and will to employ was related to the workplace conditions, e.g., the size of the workplace, work load and financial capacity. The importance of job-matching was also typically emphasized, where a task that can be well performed by one employee with disability might not be as well performed by another employee with a different disability. Furthermore, being able to offer tasks that could be performed after a shorter introduction and with little supervision was seen as improving the employability for people with disabilities. If there was a shortage or balance of labor within the occupation also affected how easily employers could find employees, with and without disabilities. Increased knowledge among employers regarding disabilities, legislation, and the available support were perceived to promote employability.

In this category, the structure of the cooperation with authorities, i.e., how support was organized, was perceived as influencing employability. Agreements, transparency, and clarity concerning the aim, purpose, and setup as factors were emphasized. Employer-oriented cooperation and support that met both the employees’ and the employers’ needs were perceived to promote employability. In contrast, an authority-oriented support that did not take the employers’ needs into account, was perceived to hamper employability. Central to the view of employability as conditional was the perception that different aspects of the character of the support could facilitate or hamper employability, depending on its configuration and content in relation to the employers’ and employees’ needs. Important aspects included financial support, which was seen as something that compensates for possible negative effects associated with adapting work tasks, and thus strengthens the employers’ view of a person with disabilities as contributive. Another crucial aspect was personal support, where accessible and engaged contacts were considered as enabling employment; and concerns regarding labor law and the regulatory framework emphasizing risks of extra costs concerning sick leave, health care and production loss for employees with disability.

Contrastive analysis

Three themes emerged as common for the three categories; trust, contribution, and support, which were seen as affecting employability in different ways. The three themes represent dimensions that cut across all categories, even if the discerned aspects of employability for people with disabilities are related differently to each other in the respective category.

The first theme, trust was a crucial issue that affected employers’ views across all categories and approaches concerning employees with disabilities, and also concerning the authorities involved. Depending on the interplay between the different underlying aspects, trust had different levels of importance for employability. For employers with a view of employability as constrained by disability, lack of trust in employees with disabilities as well as the authority contact person had a restrictive impact on employability. Lack of trust reinforced a negative “us-and-them” thinking (as illustrated in the quotes in , which focuses people with disabilities as unreliable and less valuable to the workplace) and showed that the employers made a distinction between people with disabilities and those without, with the purpose of excluding people with disabilities from the workplace. The statements typical of the perception of employability being constrained by disability, as described in the first category, demonstrate a such a lack of trust in people with disabilities, and a belief that they cannot be relied on to do what is expected of them, such as to turn up on time or perform the requested tasks.

The second theme, whether or not people with disabilities were considered to contribute to the workplace, was related to the employers’ need for labor and the character of the work. For employers with a view that employability was constrained by a disability, people with disabilities were not considered contributive. Instead, disabilities and reduced work capacity were perceived as being energy-, time-, and resource-demanding, without adding value to the workplace. People with disabilities were described in terms of being more of a burden than an asset, and thereby did not contribute to the work force and workplace. This can be contrasted with the independent and conditional views, where the statements are focusing on disability not being an obstacle, either because the inclusion of people with disabilities is rewarding in itself, or because it must be situated in the specific context of the job (see ).

The third theme that was discerned across the categories was support. Both the character of support (financial, environmental, personal and educational) and the structure (how support is organized) were crucial for the employability of people with disabilities and were closely related to employers’ views of trust and contribution. Employers with a view that employability is constrained by disability expressed criticism regarding both how the authority organized the support, as well as the character of the support, stating that it was not dynamic or employer-oriented, but was fixed and designed to suit the authority and the employee. Lack of appropriate and requested support consolidated the view that people with disabilities are not contributive and reliable, which impaired their opportunities for inclusion in the labor market. Typically, views in this category were also characterized by distrust in the authorities, where a common perception is that the support is not adjusted to meet employers’ needs, but rather to suit the authorities and the employees. The support was also seen as unreliable, e.g., where financial support could suddenly be withdrawn (see ). The internal relationships between the aspects of insufficient authority support, distrust toward the authorities and employees, and the view of people with disabilities as not contributing, can be seen as a distanced “us-and-them” thinking. This way of thinking builds on perceived differences between people with and without disabilities and prevents people with disabilities from being included in the labor market.

When contrasting the “us-and-them” thinking with the view of employability being independent of disability, as described in the second category, the statements were instead characterized by a solution-oriented approach with a “look-for-the-good” way of thinking. Typical of this view is to focus on how an employee’s work capacity can be put to use, rather than on his/her disability and reduced work capacity. Unlike the constrained view, the independent view is characterized by trust in people with disabilities and a conviction that with adequate competence and experience, the right personal characteristics, an interest in the professional area, and/or a willingness to work, the disability can be compensated for. In contrast to the constrained view, where the group is perceived as being demanding, the independent view consists of perceptions of people with disabilities as a resource and as assets to the workplace and is characterized by descriptions of the group as contributing concerning resources, time, and energy. The view of support in the independent view is distinguished by the perception that support can facilitate employment, but that it is not a prerequisite. Employability is related to the work ability of the employee and having the right person in the right place, regardless of disability, rather than support from authorities.

The third view of employability as conditional, as described in the third category, is yet again different from the “us-and-them” and the “look-for-the-good” views. This third view was characterized by a relativistic approach and “it-depends” thinking, emphasizing the contextual importance for employability and finding the right person for the right job. Compared to the other views, the conditional view is situational, where employers try not to decide whether disability is constrained by or independent of disability, takes into account different individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects in the specific work environment and in specific tasks. Trust, contribution, and support are then conceived as relational to the environment and the disability.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to increase the understanding of employers’ views of the employability of people with disabilities. The results contribute to a broadened description of the employers’ views, and shows how these different views can be understood by the interplay between different individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects, and the themes of trust, contribution, and support, as presented in .

Figure 1. The outcome space describing the interplay between different individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects, the themes from the contrasting analysis, and the employers’ views of employability.

The results show that employers’ views of the employability of people with disabilities are multifaceted and suggest the need for nuanced ways to understand the employers’ perspectives. Firstly, the categorization of the views of employability as being constrained by disability, independent of disability, and as conditional contributes a new perspective of understanding employers. The categorization provides a way of naming the employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities. Secondly, we suggest that the analysis of the complex interplay between different individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects provides a possibility to understand how the different views are built up and how they are related to the cross-cutting themes of trust, contribution and support in qualitatively different ways. In the following, we discuss how the findings of our study relate to previous research, and what this study adds.

Our first cross-cutting theme of the analysis is trust. Distrust in people with disabilities has been found in previous research to be related to different factors, for example, financial concerns [Citation6,Citation9,Citation10], work ability [Citation5,Citation6], and specific disabilities [Citation3,Citation4,Citation21]. Our study adds to the understanding of employers’ distrust in people with disabilities by also pointing out how the lack of trust in the authority contact person contributes to a view of employability as being constrained by disability.

For employers with a view of employability as independent of disability, trust instead was discernible both in employees with disabilities as well as in the involved authority contact. Our findings show that a “look-for-the-good” mode of thinking was associated with a conviction that disability does not need to be a barrier to employment. This view is in accordance with previous studies where trust has been related to employers’ previous experience of working with people with disabilities [Citation4,Citation8,Citation9] and studies where employers attribute certain positive qualities to people with disabilities, such as good attendance and reliability [Citation4,Citation22].

Previous research has described trust as a precondition for successful collaboration [Citation23]. The importance of trust and openness between the employer and employee was also emphasized in a study by Andersson et al. [Citation8]. They were considered as the highest ranking factors and were related to contextual factors such as requirements, resources, and information. Waterhouse et al. [Citation21] raised the trust of both the employer and the authority/vocational rehabilitation contact people as key issues for successful labor market inclusion. Our study adds to previous research by showing that employers viewing employability of people with disabilities as conditional, trust is not predetermined but something that is possible to influence. Trust could thus increase or decrease, depending on how different individual factors are taken into account in relation to the characteristics of the workplace and in combination with the type of support. Taken together, trust is shown to be of great significance, implying the importance of building trusting partnerships (between employers, authority contact people, and employees with disabilities) and offering employer-oriented support that not only meets the individuals’ and authorities’ needs but also the employers’ needs in order to stimulate increased labor market inclusion.

The second cross-cutting theme in our analysis found to be important in relation to views on the employability of people with disabilities was whether or not people with disabilities were considered to contribute to the workplace. These concerns about contribution constraining employability have support in several studies concerning limited possibilities to supervise [Citation12], increased costs [Citation10,Citation12], and the character of the disability, especially psychiatric and intellectual disabilities [Citation9].

In our study, employers with a view of employability as independent of disability considered people with disabilities as contributing to the workplace, where disability was not seen as something that affected the work ability. Several studies have highlighted employers’ perceptions of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities [Citation9,Citation11,Citation24], thereby supporting our findings. Between these opposing views was the view that the employability of people with disabilities was conditional on contribution to the work place. This conditional view has resemblances to findings in a study conducted by Graffham et al. [Citation14], which emphasizes that job-matching needs to be expanded from an individual performance perspective to a broader organizational perspective, considering the conditions and needs of the employer, workplace, and organization. Other studies have also stressed the importance of a good match between the right person and the right job for employment to be offered [Citation13]. Our study adds to these findings by pointing out the variation in how contribution to the workplace is seen as depending on the characteristics of the workplace and work tasks and how these relate to individual characteristics and the structure of the support.

The third cross-cutting theme in our study highlights the importance of support as paramount for how the employability of people with disabilities is perceived by employers. Both the character of support (financial, environmental, personal, and educational) and the structure (how support is organized) were crucial for the employability of people with disabilities and were closely related to employers’ views of trust and contribution. Employers with a view that employability is constrained by disability expressed criticism both regarding how the authority organized the support, as well as the character of the support, stating that it was not dynamic or employer-oriented, but was fixed and designed to suit the authority and the employee. Lack of appropriate and requested support consolidated the view that people with disabilities are not contributive or reliable, which impaired their opportunities for inclusion in the labor market. Our findings support similar results found in previous research [Citation5].

For employers with a view that employability is independent of disability, support was not a prerequisite but something that could facilitate employability. To have that effect, the support needed to be dynamic, suitable, and sufficient and not only directed towards to the employees’ and authorities’ needs but also the employers’ needs. Having the right support strengthened employers’ views of people with disabilities as being contributive and of both employees and authority contact persons as being trustworthy. This positive view of support has been found in several studies related to the experience of supported employment programs or cooperation with vocational rehabilitation agencies [Citation3].

For employers that viewed the employability of people with disabilities as being related to contextual factors, support can influence employability. It can hamper or facilitate, depending on how it is adapted to the needs of the person with the disability and the employer in relation to the workplace and job requirements. This accentuates the importance of a dynamic design of support, which should be adapted not only to the needs of employees with disabilities and authority contact people, but also to the needs of employers. These results are in line with other studies that have emphasized the importance of organizing support in a way that addresses the employers, and ensuring it has a content that increases their view of employees with disabilities as contributive and trustful [Citation3]. The importance of this individualized and specialized employer support, where employers are treated as partners and where their context is in focus, has been recognized in previous studies and has been suggested to be an essential ingredient of successful workplace inclusion [Citation5,Citation9,Citation22].

Study limitations and strengths

A wide variety of employers were selected to take part in the study, producing a mixed group with varying backgrounds and experiences of hiring people with disabilities. One of the strengths of this study was the fact that several of the employers had no experience of hiring or working with people with disabilities and some had resigned from previous collaboration with the autorities due to dissatisfaction. Thus, our study design addresses the problem of self-selection from previous studies. However, and for obvious reasons, not all professional areas were covered in this study, which could be seen as a limitation. It needs to be taken into consideration that the aim of a qualitative study is not to generalize findings to a broader population, and that a strategic sample drawn in a different context may result in somewhat different results. The findings of this study have been presented in different local contexts for politicians and vocational rehabilitation professionals, as a way of ensuring the credibility of the results. Transferability may be limited to contexts with a similar labor market and vocational rehabilitation systems.

The phenomengraphic approach has provided insight into the complexity of employers’ qualitatively different views on the employability of people with disabilities. The outcome space of the phenomenographic analysis can hence be used as a tool to understand why and how different aspects may impact on different employers’ views. The perception of structural relationships among the categories is one of the epistemological assumptions of phenomenography and is shown in this study through the cross-cutting themes trust, contribution and support. A certain aspect can be conceived as either constraining or enabling, depending on the interplay with other individual-, workplace- and authority-related aspects. Identifying the internal and structural relationships among the categories in the outcome space is an important additional part of the analysis in phenomenography, which is often not included in other qualitative methods of analysis such as content or thematic analysis [Citation20]. The insights drawn from our study of the variation in how conceptions of employability of people with disability are built up may be part of the explanation for the inconsistencies in results from previous research in this field [Citation3], and the lack of consensus concerning what aspects hamper or promote labor market inclusion. Detailed knowledge about how the different views are built up may also provide possibilities to tailor strategies for increased labor market inclusion of people with disabilities.

Future studies can build upon the findings and continue to advance our understanding of employment and disabilities. In particular, further research needs to address how partnerships between rehabilitation professionals and employers can be constructed and how employer-oriented support can be introduced to increase labor market inclusion.

Conclusions

This study has contributed a new way of describing and categorizing employers’ views on the employability of people with disabilities. The study presents a framework for understanding employers’ different views of employability for people with disabilities. Based on different understandings of the interplay between underlying individual-, workplace-, and authority-related aspects, the analysis revealed three qualitatively different views of employability, as: constrained by disability, independent of disability, and conditional. These views are also characterized on a meta-level through their association with the cross-cutting themes: trust, contribution, and support. Knowledge of the variation in conceptions of employability for people with disability offers a possibility for rehabilitation professionals to tailor employer-oriented support for trustful partnerships. Such partnerships may enhance employers’ trust in people with disabilities, which in turn may enable employers to view people with disabilities as being contributive, and thereby increase their labor market inclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Statistics Sweden. Situationen på arbetsmarknaden för personer med funktionsnedsättning; 2015 (The labour market situation for people with disabilities 2015). 2016. Report No.: 2016:1.

- Lengnick-Hall ML, Gaunt PM, Kulkarni M. Overlooked and underutilized: People with disabilities are an untapped human resource. Hum Resour Manag. 2008;47:255–273.

- Gilbride D, Stensrud R, Vandergoot D, et al. Identification of the characteristics of work environments and employers open to hiring and accommodating people with disabilities. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2003;46:130–137.

- 1wJu S, Roberts E, Zhang D. Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities: a review of research in the past decade. J Vocat Rehabil. 2013;38:113–123.

- Shaw L, Daraz L, Bezzina MB, Patel A, Gorfine G. Examining macro and meso level barriers to hiring persons with disabilities: a scoping review. Res Soc Sci Disabil. 2014;8:185–210.

- Erickson WA, von Schrader S, Bruyère SM, et al. The employment environment: employer perspectives, policies, and practices regarding the employment of persons with disabilities. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2014;57:195–208.

- Houtenville A, Kalargyrou V. Employers’ perspectives about employing people with disabilities: a comparative study across industries. Cornell Hosp Q. 2015;56:168–179.

- Andersson J, Luthra R, Hurtig P, et al. Employer attitudes toward hiring persons with disabilities: A vignette study in Sweden. J Vocat Rehabil. 2015;43:41–50.

- Hernandez B, Keys C, Balcazar F. Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities and their ADA employment rights: a literature review. J Rehabil. 2000;66:4–16.

- Kaye HS, Jans LH, Jones EC. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:526–536.

- Morgan RL, Alexander M. The employer’s perception: employment of individuals with developmental disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2005;23:39–49.

- Domzal C, Houtenville A, Sharma R. Survey of Employers’ Perspectives on the Employment of People with Disabilities: Technical Report. Office of Disability and Employment Policy, U.S. Department of Labor.; 2008. Contract No.: No. GS10F006M, B03-009.

- Gustafsson J, Peralta JP, Danermark B. The employer’s perspective: employment of people with disabilities in wage subsidized employments. Scand J Disabil Res. 2014;16:249–266.

- Graffam J, Smith K, Shinkfield A, et al. Employer benefits and costs of employing a person with disability. J Vocat Rehabil. 2002;17:251–263.

- Greenwood R, Johnson VA. Employer perspectives on workers with disabilities. J Rehabil. 1987;53:37–45.

- Zappella E. Employers’ attitudes on hiring workers with intellectual disabilities in small and medium enterprises: an Italian research. J Intellect Disabil. 2015;19:381–392.

- Marton F. Phenomenography - Describing conceptions of the world around us. Instr Sci. 1981;10:177–200.

- Stenfors-Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren MA. A phenomenographic approach to research in medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47:261–270.

- Sjöström B, Dahlgren LO. Applying phenomenography in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:339–345.

- Åkerlind GS. Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. High Educ Res Dev. 2012;31:115–127.

- Kimberley H, Glover J, Jonas P, Waterhouse P. What would it take? Employers’ perspectives on employing people with a disability. Australian Government, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; 2010.

- Graffam J, Shinkfield A, Smith K, et al. Factors that influence employer decisions in hiring and retaining an employee with a disability. J Vocat Rehabil. 2002;17:175–181.

- Huxham C. Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Manag Rev. 2003;5:401–423.

- Chi CG-Q, Qu H. Integrating persons with disabilities into the work force. Int J Hosp Tour Admin. 2003;4:59–83.