Abstract

Purpose: The purpose was to investigate how physical function is assessed in people with musculoskeletal disorders in the low back. Specifically:

Which questionnaires are used to assess physical function in people with musculoskeletal disorders in the low back?

What aspects of physical function do those questionnaires measure?

What are the measurement properties of the questionnaires?

Materials and methods: A systematic review was performed to identify questionnaires and psychometric evaluations of them. The content of the questionnaires was categorised according to the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health, and the psychometric evaluations were categorised using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) checklist.

Results: The questionnaires measured disability or ability to cope in everyday life, rather than physical function as such. Different aspects of a person’s mobility and ability to attend to one’s personal care were most often included regarding activity and participation. For body functions, items about sleep and pain were most often included. The Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale showed adequate psychometric properties in most evaluations.

Conclusions: The extent of psychometric evaluations differed substantially, as did the items included. Focus of measurement was predominantly on activities in daily life.

Valid and reliable instruments that measure relevant aspects of low back disorders are needed to provide early diagnostics and effective treatment.

Most questionnaires need more psychometric evaluations to establish the quality.

The Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale showed adequate psychometric properties in most evaluations.

The results may be useful when making decisions about which measurement instruments to use when evaluating low back disorders.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are promising tools for diagnosing a patient’s condition prior to treatment, and for evaluating intervention effects, since they provide necessary information without the need and considerable cost for staff to perform examinations or interviews. In musculoskeletal research and practice, a variety of self-reported measures have been used for this purpose [Citation1–4]. The lack of consistency in selecting self-reported outcome measures may partly be explained by the diversity of symptoms and function in patients with musculoskeletal disorders in different regions. Nevertheless, the use of different PROMs in studies on similar populations makes it difficult to compare results, and thereby draw conclusions about, for example, which interventions are most effective. This problem has previously been addressed in several studies attempting to promote a more standardised use of outcome measures [Citation5,Citation6].

A closer examination of the items included in some questionnaires also shows that it is unclear which components and aspects of function and disability are actually being measured. According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation7], it may be components related to body functions and body structures, i.e., impairment level, or components related to activities and participation. To correctly diagnose patients and provide specific, targeted interventions for them, we need to distinguish physical function per se (e.g., ability to bend forward) from the consequences of daily life (e.g., ability to do housework). ICFs view of disability builds on the biopsychosocial model, which incorporates different perspectives on health, both the medical (as body functions and structure) and the social (as activity and participation) [Citation8]. The definitions used are “the term functioning refers to all body functions, activities, and participation, while disability is similarly an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions” [Citation8,p.2].

In addition to content, the quality of the instrument is important when deciding which instrument to use. Previous research shows a varying quality among questionnaires and a need to further study their psychometric properties [Citation5,Citation6]. A standardised set of criteria for determining which properties have been evaluated for an instrument is the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN checklist) [Citation9–12]. The checklist also provides an opportunity to evaluate the validity and reliability of an instrument [Citation3,Citation13]. More details on the checklist are provided in the Materials and methods section.

A previous review of questionnaires for measuring physical function in people with musculoskeletal disorders in the neck found that the questionnaires differed substantially in items as well as the extent to which their psychometric properties had been evaluated [Citation3]. Further, it was concluded that the focus of measurement was on activities in daily life rather than physical function as such [Citation3]. In this study, PROMs intended and evaluated for measuring physical function in people with MSD in the low back were investigated. To delimit the review to studies performed on a homogeneous sample, we excluded studies where the questionnaires have been used in populations with symptoms due to trauma, infection, systemic diseases, and congenital or acquired deformities.

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate how physical function is assessed in people with MSD in the low back. Specifically, we aimed to determine:

Which questionnaires are used to assess physical function in people with MSD in the low back?

What aspects of physical function do those questionnaires measure?

What are the measurement properties of the questionnaires?

Materials and methods

Search for questionnaires

In this systematic literature review [Citation14,Citation15] we searched the data bases PubMed, Cinahl, Web of Science, and PsycInfo for studies published in English until 12 September 2017. The keywords used in the search () were defined according to the PICO model [Citation16]. Thus, keywords were selected for P (population), I (intervention), O (outcome), while C (comparison) was excluded as comparative studies were not the focus of this study.

Table 1. Keywords sorted in word groups.

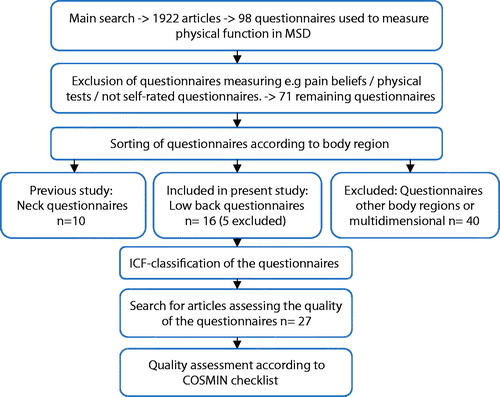

The systematic literature review process is illustrated in a flow chart (). The literature search resulted in a total of 1922 articles; in PubMed 1333 articles, in Web of Science 457 articles, in PsycInfo 91 articles, and in Cinahl 41 articles. After excluding duplicates, the selection of relevant articles to include was performed by reviewing the title and abstracts first. At this stage, 284 articles were included from PubMed, 139 articles from Web of Science, 0 articles from Cinahl, and 0 articles from PsycInfo. Thereafter the abstracts, and when needed the full text, of the articles were reviewed to find articles presenting the original version of questionnaires for measurement of physical function in MSD. For this article, questionnaires aimed to measure physical function in people with MSD in the low back were selected. Both authors performed the review separately and then discussed the selection, to reach consensus. Questionnaires regarding general health, spinal stenosis, scoliosis, anchylosing spondylitis, surgical procedures, sciatica, ratings of functional capacity, work disability, not PROMs, and questionnaires for use among specific occupational groups or adolescents/children were excluded.

A total of 98 different questionnaires for measurement of physical function in people with MSD were identified. Of these, 16 questionnaires focused on physical function in people with MSD in the low back and fulfilled our criteria for inclusion. These questionnaires were classified according to the ICF [Citation7] to determine their focus of measurement and coverage of items. The ICF has previously been evaluated in different groups with varying results, from a low reliability and need for modification when tested in geriatric care [Citation17] to acceptable reliability and reliability among people with osteoarthritis [Citation18] and children with autism [Citation19]. In this study, the ICF-classification was performed independently by both authors, and was followed by a comparative discussion to reach consensus.

Search for quality assessment of questionnaires

To identify the measurement properties that have been evaluated for the questionnaires, a second literature search in the previous databases was performed using the key words “validity OR reliability OR responsiveness AND low back AND name of questionnaire” to find articles that had quality-assessed the questionnaires. Only articles that analysed the original version of the questionnaire were included. Studies that met our previously used exclusion criteria were excluded, as well as studies concerning translated versions of the questionnaires. The translated versions were excluded to reduce the extent and complexity of the study.

Quality assessment of the questionnaires

The methodological quality of the questionnaires was examined with respect to relevant quality indicators of validity and reliability using the COSMIN checklist [Citation10,Citation12]. The COSMIN checklist contains standards for design and statistical methods to assess psychometric properties of PROMs. For further information go to the COSMIN checklist [Citation20]. Relevant psychometric properties defined by the COSMIN group can be found on p. 9. The examination of psychometric properties was performed by both authors, first separately, then together to reach consensus regarding which properties of methodological quality had been assessed for each questionnaire, and the level of quality of the questionnaires. We rated the findings of the measurement properties as “adequate” or “not adequate” according to guidelines in the COSMIN checklist. Our quality criteria were identical to those used in the previous review of questionnaires measuring physical function in people with MSD in the neck [Citation3], and are listed below.

Internal consistency (adequate = unidimensional (sub)scale or Cronbach’s alpha(s) ≥ 0.70; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Reliability (adequate = intraclass correlation/weighted Kappa ≥0.70 or Pearson’s r ≥ 0.80; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Measurement error (adequate = standard error of measurement, smallest detectable change or limits of agreement presented; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Content validity (adequate = the target population was involved in the development of the questionnaire; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Construct validity (adequate = factors explained at least 50% of the variance; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Criterion validity (adequate = correlation with criterion instrument(s) ≥ 0.50; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Responsiveness (adequate = correlation with anchor instrument ≥0.50 or area under receiver operator curve ≥0.70; not adequate = otherwise or cannot be determined).

Interpretability was marked “all” if the distribution of scores, floor/ceiling effects, scores for relevant groups and minimal important change or minimal important difference were reported, and “some” otherwise.

For criterion validity, only questionnaires (i.e., not single scales such as visual analogue scales) were considered as criterion instruments. If an instrument (either evaluated instrument or criterion instrument) contained several scales, the methodological quality was determined by taking the lowest rating of any of the scales.

Results

We identified 16 questionnaires that are used to assess physical function among people with low back pain [Citation21–36]. These questionnaires are listed in .

Table 2. Included low back questionnaires.

Questionnaire content

The classification of questionnaire items according to the ICF shows that most questionnaires only included items regarding the components body functions and activity and participation, with an overweight on items assessing activity and participation (). The Extended Aberdeen Spine Pain Scale, the Low Back Outcome Score and the Lumbar Spine Outcomes Questionnaire differed by also including items about environmental factors, and the Istanbul Low Back Pain Disability Index differed by only including items about activity and participation.

Table 3. ICF classification of the included low back pain questionnaires.

Within the component body functions, most questionnaires included items assessing “mental functions”, “sensory functions and pain”, “gender-, urinary- and reproductive functions”, and “neuromusculoskeletal and movement related functions.” For mental functions, the most common item assessed was “sleep functions” (b134). For sensory functions and pain, “pain” (b280) was most commonly assessed. For gender-, urinary- and reproductive functions, “sexual functions” (b640) was most common, while items concerning “muscle power” (b730) were most frequently used to assess neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions.

Within the component activity and participation, items regarding mobility were most common, such as “walking” (d450), “maintaining a body position” (d415) and “changing basic body position” (d410). Also rather common were items regarding personal care, such as “dressing” (d540), followed by items regarding domestic life such as “doing housework” (d640), community, social and civic life as “recreation and leisure” (d920), and important areas of life as “work and employment” (d859). The questionnaires with widest coverage of items in different areas were the Lumbar Spine Outcomes Questionnaire [Citation22], the Extended Aberdeen Spine Pain Scale [Citation36] and the Low Back Outcome Score [Citation32] (See ). An overview of all ICF-codes that were included in the analysed questionnaires can be found in .

Table 4. ICF codes with explanations.

Methodological quality

In the search for studies evaluating measurement properties of the 16 questionnaires, we identified 27 articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria [Citation21–48]. shows the extent to which each questionnaire has been evaluated. The methodological quality of the questionnaires is summarised in .

Table 5. Mapping of psychometric assessment of the included questionnaires.

Table 6. Methodological quality of the included questionnaires.

While the majority of the questionnaires have been evaluated in few studies, the evaluations tend to cover most properties of the COSMIN checklist. The most frequently evaluated questionnaires were the Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (in 6 and 4 studies, respectively). The latter questionnaire has also been evaluated for all properties in the checklist. Notably, test–retest reliability has been assessed for almost all questionnaires, while measurement error has been assessed for only 5 of the 16 questionnaires.

Internal consistency was found adequate in all of the studies investigating the property. For all but North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument; however, it was only evaluated in a single study. Test-retest reliability varied between the questionnaires. For Low Back SF-36 Physical Functioning and Oswestry Disability Index, their reliability was confirmed in two studies each. Measurement error was reported adequately for the Bournemouth Questionnaire (in one study), Low Back SF-36 Physical Functioning (in two studies), Oswestry Disability Index (in two studies), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (in three studies), and Spine Functional Index (in one study). For half of the questionnaires, content validity was found adequate, and for 5 of the 16 questionnaires it was not reported in any of the studies investigated. When assessing construct validity, we found that factor analysis of the construct to be measured had been performed for few questionnaires, and generally only in one study. The exception was the North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument, where it had been performed in three studies, and the results were inconsistent.

For criterion validity, the findings were rated for each of the criterion instruments listed in . The two most commonly used criterion instruments were Oswestry Disability Index and the Short Form 12 or 36 Item Health Survey (SF-12/SF-36). For Oswestry Disability Index, the results were inconsistent. Its correlation with Istanbul Low Back Pain Disability Index and the Low Back Outcome Score was high, while its correlation with Lumbar Spines Outcome Questionnaire and Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale was low. For SF-12/SF-36, the criterion validity towards other questionnaires was low. The Waddell questionnaire was used as criterion instrument in three studies, showing high correlations with Istanbul Low Back Pain Disability Index, Low Back Outcome Score, and ProFitMap-Low Back. Responsiveness has been evaluated for 10 of the 16 questionnaires, and was consistently found to be adequate for Oswestry Disability Index and Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale.

In addition to the ratings of quality, we assessed the degree to which important characteristics relating to the instrument’s interpretability was reported in the studies. Almost all studies reported some characteristics of the instrument, but only one study evaluating Maine-Seattle Back Questionnaire reported all characteristics considered important.

Discussion

Questionnaire content

Based on our findings, we can conclude that the questionnaires tend to measure disability or the ability to cope in everyday life, rather than physical function as such. The same result was found in our previous review of the content of neck questionnaires [Citation3]. A few previous studies have reviewed the content of low back questionnaires and classified it according to ICF [Citation6,Citation49–51]. However, comparisons do not come straightforward, as there are differences in design between the studies. Due to different search strategies (e.g., different keywords, or selection of widely used questionnaires) and/or different target samples, different instruments are evaluated in the studies. In the review by Grotle et al. [Citation6], 6 of the 36 included questionnaires were also identified in this study. For Wang et al. [Citation49], 6 of the included 15 questionnaires overlapped with this study, for Oner et al. [Citation50], only 2 of the included 17 questionnaires were included in this study, and for Sigl et al. [Citation51] 2 of the 3 were included. The corresponding questionnaires were Low Back Outcome Score [Citation6,Citation49,Citation50], Oswestry Disability Index [Citation6,Citation49–51], North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument [Citation6,Citation49,Citation51], Bournemouth Questionnaire, Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale [Citation6,Citation49,Citation51], Low Back Pain Rating Scale [Citation6], and Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire [Citation49].

When comparing the ICF categorisations that have been performed in the different reviews and this study, some similarities and differences in the results are noticeable. Among the questionnaires analysed in this study and by Wang et al. [Citation49], the classifications of the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale corresponded the most, as Wang et al. only had one category that was not included in our classification (d210 Undertaking a single task), we had only two that were not included in theirs (d460 Moving around in different locations, d630 Preparing meals), while the remaining 10 where the same. For the Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire, the correspondence was less: nine categories were the same, while three were only identified in this study (b126 Temperament and personality functions, d460 Moving around in different locations, d859 Work and employment, other specified and unspecified) and four identified only by Wang et al. [Citation49] (d230 carrying out daily routine, d455 moving around, d845 acquiring, keeping and terminating a job, e3 support, and relationships). The classifications of the Bournemouth Questionnaire corresponded for six categories, while there were eight categories specific to this study (b140 attention functions, b289 sensation of pain, other specified and unspecified, d410 changing basic body position, d450 walking, d460 moving around in different locations, d760 family relations, d859 work and employment, other specified and unspecified, d910 community life) and five to the study by Wang et al. [Citation49] (d210 undertaking a single task, d430 lifting and carrying objects, d560 drinking, d845 acquiring, keeping and terminating a job, d850 remunerative employment).

In the three reviews considering the North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument, eight categories corresponded between the classification of Wang et al. [Citation49], Sigl et al. [Citation51] and this study, while two categories were unique in this study (b640 sexual functions, d470 using transportation), and three in the study by Sigl et al. [Citation51] (b265 touch function, b730 muscle power functions, and e115 products and technology for personal use in daily living). Unfortunately, it was not possible to compare ICF categories with the review by Grotle et al. [Citation6], since their ICF-classification was not presented in sufficient detail. The best correspondence between our ICF-categorisation and that of previous reviews was obtained for the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale [Citation49] and the North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument [Citation49,Citation51], while the largest differences were found for the Low Back Outcome Score [Citation49,Citation50] and the Oswestry Disability Index [Citation49–51].

The differences in findings are somewhat surprising, since all studies have used the same ICF model. A closer look at the reviews showed that Wang et al. [Citation49], Oner et al. [Citation50], and Sigl et al. [Citation51] refer to linking rules described by Cieza et al. [Citation52,Citation53]. Initially, 10 linking rules were recommended in an effort to systematise and standardise the linking of items in PROMs to the ICF [Citation52]. Later, these linking rules were redefined and reduced to four [Citation53]. It is possible that the use of the linking rules, or different versions of the linking rules, could explain some of the differences in findings between the studies. In this study, and in the study by Grotle et al. [Citation6], the linking rules were not applied. Since one aspect of the linking rules is the categorisation of the cause (e.g., pain) as well as the impairment (e.g., ability to walk) in an item comprising both, and we aimed to identify primarily the aspect of physical function covered, e.g., limited ability to walk because of pain, we categorised only the impairment part of such items. On an item level, we believe it is a more valid use of the ICF categorisation to distinguish between items measuring pain only (which belong to body functions, sensory functions, and pain), from those measuring the impairment (e.g., ability to walk, which belong to activity and participation, mobility). On the other hand, additional categorisations of several aspects that constitute clarifying examples of a concept do not reduce the validity, as they provide more information regarding the same domain (e.g., activity and participation). Another noticeable difference between categorisations in different studies was the level of detail. For example, Wang et al. [Citation49] identified the categories “undertaking a simple task” (d 210) and “carrying out a daily task” (d 230) in the Bournemouth Questionnaire, Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire, Quebec Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, and Low Back Outcome Score. Since these are quite general categories, they may have been more precisely categorised in the other studies. More detailed investigations of how the formulation of questions in the questionnaires with the highest correspondence in ICF classification differs from those with the lowest may be warranted.

Methodological quality

Among the questionnaires investigated in this study, the most frequently evaluated questionnaires were the Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. The responsiveness of these questionnaires was found adequate in repeated studies. For the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale, measurement error was reported in the studies assessing responsiveness. Remaining quality aspects of the Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale were evaluated in no or few studies, or found inconsistent between studies. We recommend that they be evaluated for more quality aspects in more studies, to increase the utility of the questionnaires.

Unfortunately, the questionnaires with the widest coverage in items were evaluated for few quality aspects in few studies. In our literature search, we found only one study evaluating the Lumbar Spine Outcomes Questionnaire and the Extended Aberdeen Spine Pain Scale, respectively. Although the Low Back Outcome Score was evaluated in three studies, each of the quality aspects (i.e., internal consistency, reliability, criterion validity, and responsiveness) was evaluated in a single study. Thus, more studies of the psychometric properties of these questionnaires would be needed to appreciate the benefit of using them in research and practice.

Previous reviews have also found that the Oswestry Disability Index shows good responsiveness and, although evaluated to a lesser extent, test–retest reliability [Citation6,Citation50]. Further, others have concluded that the Low Back Outcome Score shows promising psychometric properties, but they need to be confirmed in more studies [Citation6,Citation50]. In this review, and in the review by Grotle et al. [Citation6], the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale showed good responsiveness. However, contrary to Grotle et al., we found inconsistent results with respect to test–retest reliability. This difference in findings may depend on the criteria used for determining adequate reliability. For the Bournemouth Questionnaire, we did not find acceptable responsiveness, as concluded by Grotle et al. [Citation6]. Both reviews found good construct validity for the Low Back Pain Rating Scale, albeit evaluated in only one study in this review. In terms of test-retest reliability, however, our results differed. For the North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability were found adequate in this review as well as in Grotle et al. [Citation6], while our findings with respect to construct validity were inconsistent. Overall, the number of studies evaluating the questionnaires was few. Hence, the findings and comparisons between reviews should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the choice of questionnaire(s) depends on what you want to measure. This classification of content and mapping of psychometric properties of questionnaires used to measure physical function in people with MSD in the low back may be used as guidance in selecting the appropriate measure for a study. At present, the Oswestry Disability Index and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale are the most frequently evaluated questionnaires, showing adequate psychometric properties in most evaluations. Based on their coverage of items, they may be appropriate to use when attempting to assess activity and participation. Questionnaires with more weight on body functions, such as the Lumbar Spine Outcomes Questionnaire, the Extended Aberdeen Spine Pain Scale, and the ProFitMap-Low Back need to be evaluated in more studies before definite recommendations can be made. The COSMIN checklist [Citation10,Citation12] may constitute a useful tool when planning these evaluations.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- SBU. Methods for long term pain treatment. Stockholm: The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care; 2006.

- IMMPACT. Initiative on methods, measurement, and pain assessment in clinical trials. 2018 [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.immpact.org/index.html

- Wiitavaara B, Heiden M. Content and psychometric evaluations of questionnaires for assessing physical function in people with neck disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:2227–2235.

- Leahy E, Davidson M, Benjamin D, et al. Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) questionnaires for people with pain in any spine region. A systematic review. Man Ther. 2016;22:22–30.

- Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine. 1998;23:2003–2013.

- Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Functional status and disability questionnaires: what do they assess? A systematic review of back-specific outcome questionnaires. Spine. 2005;30:130–140.

- WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Short version. 2001 [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2003/2003-4-2

- WHO. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health, ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10;22.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745.

- Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:651–657.

- Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Heymans MW, et al. Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:659–670.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108.

- Fink A. Conducting research literature reviews. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications Inc.; 2010.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1435–1443.

- Okochi J, Utsunomiya S, Takahashi T. Health measurement using the ICF: test-retest reliability study of ICF codes and qualifiers in geriatric care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:46.

- Kurtaiş Y, Őztuna D, Küçükdeveci AA, et al. Reliability, construct validity and measurement potential of the ICF comprehensive core set for osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:225.

- Aljunied M, Frederickson N. Utility of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) for educational psychologists’ work. Educ Psychol Pract. 2014;30:380–392.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. HCW dV. COSMIN checklist manual. 2012 [cited 2017 May 11]. Available from: http://www.cosmin.nl/images/upload/files/COSMIN%20checklist%20manual%20v9.pdf

- Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, van den Ancker M, et al. The Maine-Seattle back questionnaire: a 12-item disability questionnaire for evaluating patients with lumbar sciatica or stenosis: results of a derivation and validation cohort analysis. Spine. 2003;28:1869–1876.

- Bendebba M, Dizerega GS, Long DM. The Lumbar Spine Outcomes Questionnaire: its development and psychometric properties. Spine J. 2007;7:118–132.

- Bjorklund M, Hamberg J, Heiden M, et al. The assessment of symptoms and functional limitations in low back pain patients: validity and reliability of a new questionnaire. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1799–1811.

- Bolton JE, Breen AC. The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain patients. Journal of Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22:503–510.

- Davidson M, Keating JL, Eyres S. A low back-specific version of the SF-36 Physical Functioning scale. Spine. 2004;29:586–594.

- Daltroy LH, Cats-Baril WL, Katz JN, et al. The North American spine society lumbar spine outcome assessment Instrument: reliability and validity tests. Spine. 1996;21:741–749.

- Duruoz MT, Ozcan E, Ketenci A, et al. Development and validation of a functional disability index for chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26:45–54.

- Fairbank JC. Why are there different versions of the Oswestry Disability Index? J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:83–86.

- Ford JJ, Story I, McMeeken J. The test-retest reliability and concurrent validity of the Subjective Complaints Questionnaire for low back pain. Man Ther. 2009;14:283–291.

- Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, et al. Japanese Orthopaedic Association back pain evaluation questionnaire. Part 2. Verification of its reliability: the subcommittee on low back pain and cervical myelopathy evaluation of the clinical outcome committee of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12:526–532.

- Gabel CP, Melloh M, Burkett B, et al. The Spine Functional Index: development and clinimetric validation of a new whole-spine functional outcome measure. Spine J. 2013. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.09.055

- Greenough CG, Fraser RD. Assessment of outcome in patients with low-back pain. Spine. 1992;17:36–41.

- Harper AC, Harper DA, Lambert LJ, et al. Development and validation of the Curtin Back Screening Questionnaire (CBSQ): a discriminative disability measure. Pain. 1995;60:73–81.

- Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, et al. The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: conceptualization and development. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:151–161.

- Manniche C, Asmussen K, Lauritsen B, et al. Low Back Pain Rating scale: validation of a tool for assessment of low back pain. Pain. 1994;57:317–326.

- Williams NH, Wilkinson C, Russell IT. Extending the Aberdeen Back Pain Scale to include the whole spine: a set of outcome measures for the neck, upper and lower back. Pain. 2001;94:261–274.

- Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2002;82:8–24.

- Demoulin C, Ostelo R, Knottnerus JA, et al. Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale was responsive and showed reasonable interpretability after a multidisciplinary treatment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1249–1255.

- Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81:776–788.

- Fukui M, Chiba K, Kawakami M, et al. Japanese Orthopaedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire. Part 3. Validity study and establishment of the measurement scale: subcommittee on Low Back Pain and Cervical Myelopathy Evaluation of the Clinical Outcome Committee of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association, Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:173–179.

- Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Concurrent comparison of responsiveness in pain and functional status measurements used for patients with low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:E492–E501.

- Hart DL, Stratford PW, Werneke MW, et al. Lumbar computerized adaptive test and Modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire: relative validity and important change. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:541–551.

- Holt AE, Shaw NJ, Shetty A, et al. The reliability of the Low Back Outcome Score for back pain. Spine. 2002;27:206–210.

- Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, et al. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference for pain and disability instruments in low back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:82.

- Morlock RJ, Nerenz DR. The SC. The NASS lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument: large sample assessment and sub-scale identification. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2002;16:63–69.

- Newell D, Bolton JE. Responsiveness of the Bournemouth questionnaire in determining minimal clinically important change in subgroups of low back pain patients. Spine. 2010;35:1801–1806.

- Taylor SJ, Taylor AE, Foy MA, et al. Responsiveness of common outcome measures for patients with low back pain. Spine. 1999;24:1805–1812.

- Aghayev E, Elfering A, Schizas C, et al. Factor analysis of the North American Spine Society outcome assessment instrument: a study based on a spine registry of patients treated with lumbar and cervical disc arthroplasty. Spine J. 2014;14:916–924.

- Wang P, Zhang J, Liao W, et al. Content comparison of questionnaires and scales used in low back pain based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1167–1177.

- Oner FC, Jacobs WC, Lehr AM, et al. Toward the development of a universal outcome instrument for Spine Trauma: a systematic review and content comparison of outcome measures used in Spine Trauma research using the ICF as reference. Spine. 2016;41:358–367.

- Sigl T, Cieza A, Brockow T, et al. Content comparison of low back pain-specific measures based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Clin J Pain. 2006;22:147–153.

- Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, et al. Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:205–210.

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:212–218.