Abstract

Aim: The aim is to assess whether the national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation with a focus on facilitating return-to-work is being implemented in health-care units in Sweden and which factors influence its implementation.

Methods: A survey design was used to investigate the implementation. Data were collected at county council management level (process leaders) and clinical level (clinicians in primary and secondary care) using web surveys. Data were analyzed using SPSS, presented as descriptive statistics.

Results: The response rate among the process leaders was 88% (n = 30). Twenty-eight percent reported that they had already introduced workplace interventions. A majority of the county councils’ process leaders responded that the national policy was not clearly defined. The response rate among clinicians was 72% (n = 580). Few clinicians working with patients with common mental disorders or musculoskeletal disorders responded that they were in contact with a patient’s employer, the occupational health services or the employment office (9–18%). Nearly, all clinicians responded that they often/always discuss work-related problems with their patients.

Conclusions: The policy had been implemented or was to be implemented before the end of 2015. Lack of clearly stated goals, training, and guidelines were, however, barriers to implementation.

Clinicians’ positive attitudes and willingness to discuss workplace interventions with their patients were important facilitators related to the implementation of a nationwide policy for workplace interventions/rehabilitation.

A lack of clearly stated goals, training, and guidelines were barriers related to the implementation.

The development of evidence-based policies regarding rehabilitation and its implementation has to rely on very structured and clear descriptions of what to do, preferably with the help of practice guidelines.

Nationwide implementation of rehabilitation policies has to allow time for preparation including communication of goals and competence assurance in a close collaboration with the end users, namely clinicians and patients.

Implications for rehabilitation

| Abbreviations | ||

| CBT | = | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| CFIR | = | Consolidated framework for implementation research |

| CMD | = | Common mental disorders |

| IPT | = | Interpersonal psychotherapy |

| MMR | = | Multimodal rehabilitation |

| RG | = | Rehabilitation guarantee |

| RTW | = | Return to work |

| SPSS | = | Statistical package for the social sciences |

Introduction

Diagnoses related to common mental disorders (CMD), such as anxiety, depression, adjustment disorders and stress-related disorders, and musculoskeletal disorders are the most common reasons for long-term sick leave in industrialized countries, including Sweden [Citation1,Citation2]. Besides the negative impact on individual well-being, economic situation and social network, the societal cost in the European Union, in terms of health care, sick leave, and productivity loss for employers, is estimated to be some EUR 620 billion annually [Citation3]. In 2015, CMD was the most common cause of sick leave among working-age women and men [Citation4].

Previous research has underlined the importance of involving the workplace early in the rehabilitation process [Citation5–7] for facilitating return-to-work (RTW) among employees on sick leave [Citation5,Citation6]. For persons suffering from mental health problems workplace intervention reduces sick leave and increases RTW compared with clinical treatment alone (i.e., psychotherapeutic therapy and/or pharmacological treatment). When added to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the involvement of the workplace increases RTW [Citation6,Citation8]. For workers with musculoskeletal disorders, multimodal rehabilitation (MMR), in combination with workplace interventions, reduces pain and improves work ability compared with other forms of care [Citation5,Citation9].

To meet rehabilitation needs in the population and to reduce a large number of people on sick leave due to CMD or musculoskeletal pain, several European countries, including Sweden, have implemented national policies, which aim to increase the rate of RTW and prevent long-term sick leave [Citation10,Citation11]. In Sweden, a national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation, the rehabilitation guarantee (RG), was introduced by the government in 2008 to provide financial support for evidence-based rehabilitation. The policy is updated annually in line with the latest developments in evidence-based rehabilitation. This paper concerns the update made in 2015.

The 2015 policies adopt Carroll et al.’s definition of a workplace intervention [Citation7]. In other words, the intervention must take place entirely or in part at the employee’s workplace, or it must involve delivery of the intervention by or in direct contact with the employer or a representative of the employer (employee’s supervisor or employer’s occupational health services) [Citation7]. The policy gives no further guidance with regard to further specifications and support for implementation.

The treatments included in the RG are MMR and psychological treatment (CBT or interpersonal therapy IPT). MMR is provided by teams that include, at least, a physiotherapist, a physician or general practitioner, and a social worker. Psychological treatment is provided by licensed psychologists, licensed psychotherapists, or social workers. Hereafter, these are referred to as clinicians. For further descriptions of the RG, see Björk Brämberg et al. [Citation12], Busch et al. [Citation13], and Supplementary Table S1.

A number of previous studies have described the factors that facilitate or impede professionals’ implementation of workplace interventions [cf. Citation14,Citation15]. One major barrier to implementation is the conflicting perspectives and interests represented by the various stakeholders [Citation16]. Factors that facilitate implementation include the coordination of RTW and close collaboration between key stakeholders, which is structured and planned; practices that activate the employee on sick leave; and adjustments in the workplace, which are an integrated part of the RTW process [Citation17].

One limitation of the studies of barriers and facilitators that have been conducted to date is that they mostly rely on qualitative data collected in relatively small-scale studies. They also often lack a theoretical base. In the present study, we use the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) [Citation18] to identify factors that may hinder or facilitate implementation. According to CFIR, implementation can be influenced by factors related to the following domains: intervention characteristics; characteristics of individuals; inner and outer settings. By looking at factors related to these domains, it is possible to identify and act on those that hinder or facilitate the nationwide implementation of a national policy. Given the magnitude of the individual and societal costs associated with sick leave, we need more in-depth knowledge about the barriers and facilitators, which affect the implementation of workplace interventions in the rehabilitation process. As barriers and facilitators are likely to differ between health-care professionals working with CMD or musculoskeletal pain, it was decided to examine these two groups of clinicians separately.

The first aim of the study is to assess whether health-care units in Sweden are in fact implementing the national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation with a focus on facilitating RTW. The second aim is to identify which factors influence its implementation. Implementation, in this case, means that health-care units are liaising with relevant stakeholders to facilitate RTW. The aims are assessed from the perspective of the county-council process leaders who are responsible for providing supporting RG implementation in health-care units, and clinicians who provide psychological treatments or MMR.

Materials and methods

This study is an evaluation of the 2015 national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation. It was commissioned by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. The study uses a survey design to investigate the implementation of the policy. It looks at the use of strategies and possible barriers and facilitators, which influence the implementation process. Data were collected from process leaders (county council management) and clinicians who provide the treatments included in the RG. The study was conducted from June to October 2015.

Study population

County council process leaders

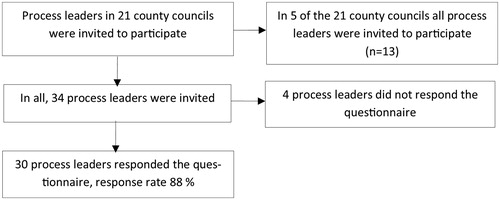

All county councils (n = 21) in Sweden were invited to participate in the study. Each county council has an assigned process leader who is responsible for supporting the clinicians with the RG. There are no official statistics regarding the total number of process leaders in Sweden. Some of the larger county councils have several process leaders, whereas the majority of county councils have just one process leader. The assigned process leader from each county council was invited to participate by email. In those county councils (n = 5) where we also included clinicians in the study, all process leaders who worked at least 50% with the RG within that county council were invited to participate (n = 13). No other eligibility criteria were used. Their email addresses were provided by the assigned process leader. In all, 34 process leaders were invited to participate ().

Clinicians working with psychological treatment or multimodal rehabilitation

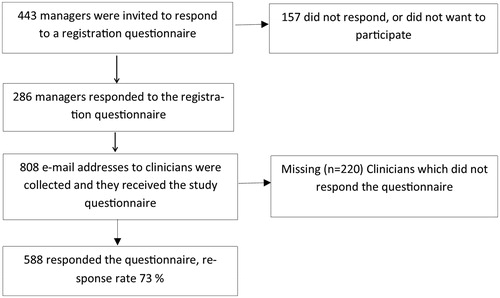

Clinicians from the county councils (n = 5) who had participated in previous evaluations of the RG also participated in the present study. The selection was based on county council size and the number of clinics working with the RG. Participants were recruited in a two-step process: first, an email describing the study was sent to all managers (n = 443) in primary and specialized care who were responsible for delivering treatments included in the RG. They were asked to provide email addresses of the clinicians (e.g., psychologists, physiotherapists) working with the RG. In all, 286 (65%) managers responded and provided the research group with the email addresses of a total of 808 clinicians. In the second step, all clinicians (n = 808) were sent an email containing detailed information about the study, including information about informed consent and an electronic link to the web survey. In all, 580 of the approached clinicians completed the web survey, a response rate of 72% ().

Data collection

Data were collected by means of two web surveys. One was sent to the RG process leaders at the county councils in June 2015 and one to the clinicians working with the RG, from August to October 2015. A detailed description of the content of the web surveys is given in Supplementary Tables SCitation2 and SCitation3. The first part of both surveys included a description of the RG 2015 policy. This included the following definition of workplace interventions: “workplace interventions refer to the contact between clinicians and the patients’ employers, the occupational health service or the employment service with the aim of facilitating possible adaptations to the workplace, work-tasks and/or vocational rehabilitation". Both web surveys were based on existing questionnaires, which were either used in previous evaluations of the RG [Citation12,Citation19] or in Swedish studies of factors which impede or facilitate implementation (unpublished studies). Additional questions were added from the CFIR guide (http://www.cfirguide.org/) [Citation18,Citation20]. Prior to distributing the web surveys by email, the surveys were reviewed by a group (n = 4) of experts in the field of CMD and musculoskeletal pain. The web surveys were then slightly revised in accordance with the recommendations of the expert group. The web surveys were also pilot-tested on two process leaders who did not then participate in the study. A 1-week test–retest was conducted for the clinicians’ web survey; the first 50 respondents completed the web survey on two occasions with a 1-week interval. The calculated weighted kappas (k) were categorized according to Landis and Koch [Citation21], with the following as standards for strength of agreement for the k: ≤0 = poor, 0.01–0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, and 0.81–1 = almost perfect.

Web survey of the county council RG process leaders

The web survey included general questions about the content of the 2015 policy (4-point scale; “very knowledgeable” to “not knowledgeable”); the timetable for introducing workplace interventions within the RG (4-point scale); and whether the instigation of workplace interventions had resulted in new recruitments, supplementary training of current personnel or reorganization. The web survey also assessed barriers to working with workplace interventions by asking respondents to indicate which from a list of nine barriers (e.g., clashes with existing routines, lack of clarity about what workplace interventions are), posed problems when working with workplace interventions. The survey’s questions and statements which relate to the CFIR domains and constructs (intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, and individual characteristics) are described in Supplementary Table S2.

Web survey of clinicians working with treatments within the rehabilitation guarantee

The web survey contained questions about the clinicians’ background (private or public employees, job title, the sick leave status of the majority of their patients); the extent to which clinics liaise with relevant stakeholders (patient’s employer, the occupational health service, the social insurance agency, and employment office) to facilitate adjustments to a patient’s workplace, work tasks, and/or vocational rehabilitation (k = 0.66–0.85); and the extent to which clinicians discuss work-related problems with their patients (k = 0.54). The web survey also featured questions relating to the domains and respective constructs of the CFIR [Citation22]. Intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, individual characteristics, and test–retest results are described in Supplementary Table S3.

Statistical analysis

The data collected by the web questionnaires were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY presented as descriptive statistics, in this case prevalence. The 5-point scales were collapsed into three categories.

Results

County council process leaders

The implementation of the policy

The response rate to the web survey was 88% (n = 30), which represents process leaders at 18 county councils. Seventy percent of the process leaders (n = 21) indicated that they were well-acquainted with the contents of the policy. For the questions about the timetable for introducing the workplace interventions of the RG-program, we included only the responses of the main county council process leader (n = 14). Twenty-eight percent (n = 5) reported that workplace interventions had already been introduced and 39% (n = 7) reported that this would be carried out before the end of 2015. Forty-six percent (n = 10) of the process leaders indicated that the county council had offered their personnel supplementary training.

describes the responses to the statements about the CFIR’s domains and respective constructs. For the domain 'intervention characteristics', 66% (n = 19) of process leaders answered that the RG 2015 policy was not clearly defined (low/very low). With regard to the outer setting, 65% (n = 17) of the process leaders indicated that they completely/partly disagreed with the statement that the county council’s management had made it clear to clinicians at the rehabilitation facilities that workplace interventions are a priority. With regard to the inner setting, the majority of process leaders indicated that their county council had no goals for workplace interventions (78%; n = 21) and no system for monitoring clinics’ work with workplace interventions (62%; n = 16).

Table 1. County council process leaders’ level of agreement with statements about the 2015 rehabilitation guarantee following the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Factors that impede or facilitate implementation

The three barriers to workplace interventions mentioned by the majority of process leaders were workplace interventions having a low priority (68%), shortcomings in the monitoring system (64%), and unclear distribution of responsibility (63%). Two facilitators of workplace interventions described by the majority of process leaders were county councils having set clear goals for workplace intervention (78%) and routines and/or guidelines being in place for how the clinics should work with workplace intervention (57%).

Clinicians who provide treatments included in the RG

The response rate to the web survey was 72% (n = 580). Sixty-one percent (n = 348) of the respondents were clinicians in CBT/IPT and 39% (n = 220) in MMR. Most clinicians in CBT/IPT worked in the private sector (64%), whereas the majority of clinicians in MMR worked in the public sector (56%). Most respondents worked in primary health care. For further information about the clinicians’ background characteristics, see .

Table 2. Characteristics of participating clinicians presented separately for clinicians working with CBT/IPT and with MMR.

Policy implementation

The survey responses revealed that only 9–18% of clinicians in CBT/IPT were in contact with relevant stakeholders other than the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (43%) to facilitate workplace interventions. Higher percentages (20–67%) were observed for clinicians working with MMR, although here too the highest percentages were accounted for by contacts with the social insurance agency. Nearly all respondents, both in CBT/IPT (90%) and MMR (90%), responded that they often-to-always discuss work-related problems with their patients ().

Table 3. Extent of contact with relevant stakeholders to enable workplace interventions.

Factors that impede or facilitate implementation

The clinicians’ responses to statements about the CFIR’s domains and respective constructs are presented in . For the domain ‘intervention characteristics’, about half of the clinicians (CBT/IPT 46%; MMR 61%) stated that there was evidence that workplace interventions increase RTW among patients. Only a small number of clinicians (12% CBT/IPT; 17% MMR) partly or completely agreed that the county council’s policy goal was clearly stated. With regard to the outer setting and the 'external policies and incentives' construct, nearly half of respondents (49% (n = 142) CBT/IPT; 43% (n = 80) MMR) completely or partly disagreed that the county council had a clearly formulated aim for workplace interventions. The responses to the statement about patient needs and resources reveal that 55% (n = 103) of MMR clinicians and 34% (n = 97) of CBT/IPT clinicians agreed that patients are generally positive towards workplace interventions.

Table 4. Clinicians’ responses to statements based on the consolidated framework for implementation research, presented separately for clinicians working with CBT/IPT (n = 348) and with MMR (n = 220).

Where the inner setting and the 'networks and communications' construct are concerned, around half (55%; n = 101) of MMR clinicians agreed that there are opportunities to discuss how barriers to workplace interventions can be overcome; this compares with only 29% (n = 84) of CBT/IPT clinicians.

Finally, for the 'characteristics of individuals' domain, more than half of CBTT/IPT (57%; n = 167) clinicians and the majority of MMR clinicians (75%; n = 141) agreed that they felt motivated to work in line with the policy.

Discussion

The present study examined the nationwide implementation of a national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation. With regard to the first aim of the study, the results showed that the implementation of the policy had been successful at the county council level, with nearly all process leaders responding that the policy had been implemented, or would be completed before the end of 2015. However, the implementation had been less successful at the clinical level. The stakeholder with which clinicians had most contact was the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. However, even though contact with stakeholders was limited, nearly all participating clinicians indicated that they often-to-always discuss work-related problems with their patients. This agrees with other studies that have found that health-care professionals initiate work-related discussions to promote RTW [Citation23].

The second aim of the study was to identify which factors influence the implementation of workplace interventions. The findings indicate that a number of factors may have influenced the low percentage of clinicians who liaised with key stakeholders to facilitate RTW. The first of these factors was the clinician’s lack of knowledge of workplace interventions; this was mentioned by both the clinicians themselves (especially those working in CBT/IPT) and the process leaders. One reason for this could be lack of training and the lack of guidelines and routines for workplace interventions. Lack of guidelines has been reported as a major problem in previous evaluations of the RG [Citation12,Citation24]. A previous study of the management of back pain through work interventions reported that lack of training and expertise in occupational health was one reason for work-related problems not being given higher priority [Citation14]. This is a factor that has also arisen in previous studies of sickness certification [Citation25,Citation26]. Poor communication about the aims and goals of the policy may consequently have hindered its implementation, which is in line with Martin et al. [Citation27].

Another factor that might have influenced the implementation of workplace interventions is whether clinicians believe that such interventions are within their job description. In the present study, there was a clear difference between the two groups of clinicians in this regard. A positive attitude to such interventions is not only important for implementation success; patients encountering supportive clinicians reported that the clinician’s attitude was essential for their rehabilitation and the RTW process [Citation16]. Furthermore, CBT/IPT and MMR are both interventions aimed at behavior change [Citation28]. Some key differences in how they address the intervention and the target groups are apparent. In Sweden, clinicians in CBT/IPT largely work on a one-to-one basis with their patients, whereas MMR is a team-based, multidisciplinary intervention [Citation29]. Our findings indicate that clinicians in MMR are more likely to report access to training, routines and/or guidelines and team cooperation, than clinicians in CBT/IPT. There are also major differences with regard to the different workplace intervention target groups, i.e., the patients. Problems related to RTW among people with common mental health disorders may be perceived as more complicated due to the risk of stigmatization at the workplace – a factor which does not affect people suffering from musculoskeletal disorders [Citation16]. For the latter patients, the most common problems with regard to RTW are a physical workload and workplace design [Citation30].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The major strength of this study is the fact that the RG has been implemented nationwide, thus giving the opportunity to include all county councils and a large nationwide sample of clinicians. Furthermore, the use of a theoretical framework CFIR [Citation18] gives a systematic, replicable, and thorough evaluation of the implementation process.

A limitation of the study is that there are no validated questionnaires and we, therefore, had to develop the questionnaires used in the study. To do this we used existing questionnaires and the interview/CFIR guide, translated into Swedish. A basic testing of content validity (face validity and expert opinion) and stability was carried out (test–retest) prior to the study start. Because of the low sample size of process leaders, we chose not to conduct a test–retest in the sample. Overall, the results of the test–retest showed moderate to almost perfect reliability. However, the reliability of the question about changing work routines demonstrated only “fair” reliability, which warrants caution when interpreting that particular question.

Another limitation is that it was not possible to include an assessment of the patient experience of taking part in workplace interventions. As suggested by Andersen et al. [Citation16], a number of individual factors (patient’s needs and resources) could influence and be an obstacle to the use and effect of these interventions. These individual factors include symptoms related to the diagnosis itself (exhaustion, reduced concentration), low self-efficacy, and lack of coordination between the health-care unit and the workplace [Citation16]. The present study assesses only clinicians’ opinions of patient needs and resources.

Lessons learned

The present study focuses on the implementation of a national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation. As previous implementation research [Citation31] has shown, the decision to implement evidence-based measures and policies is not solely a result of the research evidence, but also of societal needs and preferences, clinician skills and resources, and the context in which the measures and policies are to be implemented. This is further supported by our findings. When introducing new measures into everyday practice it is of utmost importance to consider factors such as the setting and the context, the available organizational support, and the preferences of the target groups. Our results showed that several of these factors have not been taken into consideration when introducing the RG. Given the results of the present study, we suggest that the development of evidence-based policies and their implementation must be based on highly structured and clear descriptions of what to do, preferably with the help of practice guidelines. In line with Brownson et al. [Citation32] we suggest that policy implementation should be introduced with care, with plenty of time allowed for the communication of goals and for competence assurance in close collaboration with the end users, namely clinicians and patients.

The study uses the CFIR to investigate the implementation process of the policy for workplace interventions. Thus, the results of this study can be used to facilitate the implementation of other programs which aim to improve RTW.

Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of providing training in occupational health and the importance of clinicians’ contact with employers for facilitating the implementation of workplace interventions. We conclude that future research should also investigate patient preferences regarding which actors should be involved in the process of RTW.

Conclusions

The findings about county council implementation of the policy reveal that it either had been implemented or was to be implemented before the end of 2015. Our study found that, at the clinical level, few clinicians in CBT/IPT were liaising with relevant stakeholders to facilitate workplace interventions. Higher percentages of contact were observed for clinicians working with MMR. A lack of clearly stated goals, training, and guidelines were barriers to the implementation of workplace interventions. Clinicians’ positive attitudes and willingness to discuss workplace interventions with their patients were important facilitators. The process leaders had a disseminative and educational role, even if the findings indicate highly mixed success in communicating with clinicians.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm approved the study’s design (Reg. no. 2015/303-32). The participants received written information about their participation being voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any time without having to state a reason. They were also told that it would not be possible to identify them in the report of the findings. Participants gave their informed consent by completing the questionnaire. The study was an evaluation conducted on behalf of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. The participants were informed about the research group’s independent and external role.

Supplementary_Tables_S1_to_S3.pdf

Download PDF (301.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hanna Bonnevier and Eva Nilsson for their administrative skills and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Head J, Ferrie JE, Alexanderson K, et al. Diagnosis-specific sickness absence as a predictor of mortality: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1469.

- Gjesdal S, Haug K, Ringdal P, et al. Sickness absence with musculoskeletal or mental diagnoses, transition into disability pension and all-cause mortality: a 9-year prospective cohort study. Scand J Pub Health. 2009;37:387–394.

- Matrix Insight: Executive Agency for Health and Consumers. Economic Analysis of Workplace Mental Health Promotion and Mental Disorder Prevention Programmes and of their Potential Contribution to EU Health, Social and Economic Policy Objectives. European Union; 2013.

- Försäkringskassan. Sjukfrånvarons utveckling [The development of sickness absence]. Stockholm, Sweden: The Social Insurance Agency; 2016.

- van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HC, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD006955.

- Nieuwenhuijsen K, Faber B, Verbeek JH, et al. Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD006237.

- Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, et al. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:607–621.

- Arends I, Bruinvels DJ, Rebergen DS, et al. Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006389.

- van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:19–39.

- Aust B, Nielsen MB, Grundtvig G, et al. Implementation of the Danish return-to-work program: process evaluation of a trial in 21 Danish municipalities. Scand J Work Environ Health. 20151;41:529–541.

- van Beurden KM, Brouwers EP, Joosen MC, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to enhance Occupational Physicians' Guideline adherence on sickness absence duration in workers with common mental disorders: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:559–567.

- Björk Brämberg E, Klinga C, Jensen I, et al. Implementation of evidence-based rehabilitation for non-specific back pain and common mental health problems: a process evaluation of a nationwide initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:79.

- Busch H, Björk Brämberg E, Hagberg J, et al. The effects of multimodal rehabilitation on pain-related sickness absence - an observational study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017:27:1–8.

- Wynne-Jones G, van der Windt D, Ong BN, et al. Perceptions of health professionals towards the management of back pain in the context of work: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:210.

- de Vries G, Koeter MW, Nabitz U, et al. Return to work after sick leave due to depression; a conceptual analysis based on perspectives of patients, supervisors and occupational physicians. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:1017–1026.

- Andersen MF, Nielsen KM, Brinkmann S. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on return to work among employees with common mental disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38:93–104.

- Pomaki G, Franche RL, Khushrushahi N, et al. Best Practices for Return-to-Work/Stay-at-Work Interventions for Workers with Mental Health Conditions. Vancouver, Canada: Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in BC; 2010.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2009;4:50.

- Hellman T, Jensen I, Bergstrom G, et al. Essential features influencing collaboration in team-based non-specific back pain rehabilitation: FINDINGS from a mixed methods study. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2016;30:309–315.

- Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, et al. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Sci. 2016;11:72.

- Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–174.

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. The CFIR Technical Assistance Website [Website]. Center for Clinical Management Research North Campus Research, Plymouth Rd, Ann Arbor: CFIR Research Team 2016 [updated 2014 Oct 29; cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://www.cfirguide.org/index.html

- Wynne-Jones G, Cowen J, Jordan JL, et al. Absence from work and return to work in people with back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:448–456.

- Riksrevisionen. Rehabiliteringsgarantin fungerar inte - tänk om eller lägg ner. 2015.

- Bremander AB, Hubertsson J, Petersson IF, et al. Education and benchmarking among physicians may facilitate sick-listing practice. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22:78–87.

- Money A, Hann M, Turner S, et al. The influence of prior training on GPs' attitudes to sickness absence certification post-fit note. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16:528–539.

- Martin MH, Nielsen MB, Petersen SM, et al. Implementation of a coordinated and tailored return-to-work intervention for employees with mental health problems. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22:427–436.

- Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:376–385.

- Jensen IB, Bergstrom G, Ljungquist T, et al. A 3-year follow-up of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for back and neck pain. Pain. 2005;115:273–283.

- van Oostrom SH, van Mechelen W, Terluin B, et al. A participatory workplace intervention for employees with distress and lost time: a feasibility evaluation within a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:212–222.

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Sci. 2015;10:21.

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201.