Abstract

Background: Persons with disabilities have often been overlooked in the context of HIV and AIDS risk prevention and service provision. This paper explores access to and use of HIV information and services among persons with disabilities.

Methods: We conducted a multi-country qualitative research study at urban and rural sites in Uganda, Zambia, and Ghana: three countries selected to exemplify different stages of the HIV response to persons with disabilities. We conducted key informant interviews with government officials and service providers, and focus group discussions with persons with disabilities and caregivers. Research methods were designed to promote active, meaningful participation from persons with disabilities, under the guidance of local stakeholder advisors.

Results: Persons with disabilities emphatically challenged the common assumption that persons with disabilities are not sexually active, pointing out that this assumption denies their rights and – by denying their circumstances – leaves them vulnerable to abuse. Among persons with disabilities, knowledge about HIV was limited and attitudes towards HIV services were frequently based upon misinformation and stigmatising cultural beliefs; associated with illiteracy especially in rural areas, and rendering people with intellectual and developmental disability especially vulnerable. Multiple overlapping layers of stigma towards persons with disabilities (including internalised self-stigma and stigma associated with gender and abuse) have compounded each other to contribute to social isolation and impediments to accessing HIV information and services. Participants suggested approaches to HIV education outreach that emphasise the importance of sharing responsibility, promoting peer leadership, and increasing the active, visible participation of persons with disabilities in intervention activities, in order to make sure that accurate information reflecting the vulnerabilities of persons with disabilities is accessible to people of all levels of education. Fundamental change to improve the skills and attitudes of healthcare providers and raise their sensitivity towards persons with disabilities (including recognising multiple layers of stigma) will be critical to the ability of HIV service organisations to implement programs that are accessible to and inclusive of persons with disabilities.

Discussion: We suggest practical steps towards improving HIV service accessibility and utilisation for persons with disabilities, particularly emphasising the power of community responsibility and support; including acknowledging compounded stigma, addressing attitudinal barriers, promoting participatory responses, building political will and generating high-quality evidence to drive the continuing response.

Conclusions: HIV service providers and rehabilitation professionals alike must recognise the two-way relationship between HIV and disability, and their multiple overlapping vulnerabilities and stigmas. Persons with disabilities demand recognition through practical steps to improve HIV service accessibility and utilisation in a manner that recognises their vulnerability and facilitates retention in care and adherence to treatment. In order to promote lasting change, interventions must look beyond the service delivery context and take into account the living circumstances of individuals and communities affected by HIV and disability.

Persons with disabilities are vulnerable to HIV infection but have historically been excluded from HIV and AIDS services, including prevention education, testing, treatment, care and support. Fundamental change is needed to address practical and attitudinal barriers to access, including provider training.

Rehabilitation professionals and HIV service providers alike must acknowledge the two-way relationship between HIV and disability: people with disability are vulnerable to HIV infection; people with HIV are increasingly becoming disabled.

Peer participation by persons with disabilities in the design and implementation of HIV services is crucial to increasing accessibility.

Addressing political will (through the National Strategic Plan for HIV) is crucial to ensuring long-term sustainable change in recognizing and responding to the heightened vulnerability of people with disability to HIV.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Policies and programmes have expanded across high HIV prevalence areas of sub-Saharan Africa to provide a spectrum of services for HIV and AIDS prevention, testing, treatment, care and support. However, this continuum consistently overlooks the needs and interests of persons with disabilities (including sensory, physical and intellectual disabilities) who comprise at least 15% of the population [Citation1]. While this omission has historically been attributed to the perception that persons with disabilities are not sexually active, this is a harmful fiction that is easily undermined by extensive empirical data (e.g., [Citation2–8]).

Evidence of the extent of HIV infection among persons with disabilities in Africa is scant but consistent. Reviews concur that vulnerability to HIV infection among persons with disabilities is exacerbated by sexual abuse and exploitation and compounded by a lack of access to services [Citation9–11]. A meta-analysis of HIV risk data in sub-Saharan Africa found that persons with disabilities had an elevated relative risk ratio to HIV infection of 1.31, increasing to 1.5 when focused on females only [Citation12]. Reviewers observe consistency among the risk factors predisposing persons with disabilities to HIV infection, associated with exposures to poverty, social exclusion and violence. A ground-breaking recent study in Cameroon [Citation13] – the first in the region to compare HIV prevalence among people with and without disabilities using a matched control group and probability-based sampling – found that persons with disabilities had higher prevalence of HIV infection and higher risk of sexual violence than people without disabilities, and documented stronger correlations between HIV infection and sexual risk (violence, transactional sex) among persons with disabilities than the control group. This single comparative study and the reviews emphasise that research reporting directly on HIV prevalence among persons with disabilities is limited, and the extent to which they are exposed to sexual risk is at best underestimated [Citation9–12].

Socioeconomic risk factors elevating vulnerability to HIV across the population are exacerbated among persons with disabilities, including poverty, illiteracy, and social isolation [Citation10,Citation14,Citation15]. Moreover, data suggest that the risks of HIV infection among persons with disabilities may be further heightened due to exposures to abuse and violence, lack of power within relationships, and risky (frequently non-consensual) sexual behaviours [Citation7,Citation16–18]. Multiple surveys in diverse sub-Saharan African settings have repeatedly shown lower levels of knowledge about HIV among persons with disabilities, demonstrating links with education, communication difficulties, and poverty [Citation7,Citation8,Citation19–22]. In Uganda and South Africa, lower levels of HIV knowledge among persons with disabilities (especially females) have been linked to misperceptions of risk, poor access to HIV services, and a high prevalence of unsafe and non-consensual sexual behaviours [Citation7,Citation21]. While a few specific examples of HIV education interventions aimed at persons with disabilities have been documented (e.g., [Citation5,Citation17,Citation23]), HIV educators admit to a lack of appropriate skills in communicating HIV education and prevention messages among persons with disabilities and seek specialist skills training [Citation24].

Qualitative studies in Uganda and Zambia among persons with disabilities accessing healthcare services have documented a further set of obstacles impeding persons with disabilities (and especially women) from accessing HIV diagnostic and treatment services; including enacted stigma from patients and providers, communication difficulties leading to confidentiality concerns, lack of appropriate information materials, and physically inaccessible infrastructure [Citation14,Citation25,Citation26]. Stigma remains a significant barrier to accessing services; to the extent that persons with disabilities in Zambia reported such powerful experiences of negative treatment that they were prepared to consider jeopardising their HIV treatment regimen by quitting antiretroviral therapy altogether [Citation27].

Recent global and regional policy developments have contributed to increasing recognition that persons with disabilities comprise a population group that is especially vulnerable to HIV infection, especially in high HIV prevalence regions. Participants of the Africa Campaign on Disability and HIV and AIDS issued the Kampala Declaration to call upon all African governments to include disability in its diversity as a crosscutting issue in all poverty reduction strategies, and hence to make HIV programmes equally accessible to persons with disabilities [Citation28]. Article 31 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [Citation29] notes with concern that HIV programs have been inadequately targeted or made accessible to persons with disabilities. Meanwhile, legal protections for persons with disabilities from exposure to HIV remains limited in many sub-Saharan African countries, even in those that have ratified the CRPD [Citation30]. Hanass-Hancock et al. go beyond the human rights issue to frame disability inclusion as a necessity to ending AIDS, and call for a move from the political rhetoric of inclusion to a concrete and actively inclusive approach to disability rights by improving access to HIV prevention, treatment and care as an integral step towards meeting the high profile pledge by international heads of state to end AIDS by 2030 [Citation31,Citation32]. Yet, the continuing absence of persons with disabilities from HIV programmatic and policy discussion remains notable. In most sub-Saharan African countries, the national framework for HIV response and guiding the planning and implementation of prevention, treatment, care and support activities is established in the National Strategic Plan (NSP) for HIV. In a review of 18 NSPs within Eastern and Southern Africa, less than half acknowledged the role of disability – with the implication that unmentioned priorities are unlikely ever to gain recognition on the ground in HIV program implementation [Citation33].

Since the effects of both disability and HIV go beyond the individual to their entire household and extended family, it is critical to recognise the intrinsic interconnectedness of the challenges of health (physical and emotional), disability, caregiving, employment, education, infrastructure, poverty, placing undue strain on household and community support systems [Citation34–36]. With the entire household under strain from these simultaneous challenges, O’Brien et al. propose a conceptual model that goes beyond medical challenges to show how adults living with HIV and disability may be impeded in their ability to carry out daily activities and participate in society [Citation37]. As availability of antiretroviral treatment (ART) expands, HIV is increasingly being managed as a chronic illness, albeit one uniquely affected by stigma [Citation27]. People are living longer with the virus as well as with a continuing range of opportunistic infections and other disabling health conditions that are associated with long-term disabilities (both permanent and episodic) and other emerging health challenges. A systematic review of prevalence and risk of disabilities among persons living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa found links between widespread HIV and disabilities affecting a range of body functions, including physical (25% prevalence), auditory (24.1%), and visual (11.2%) impairments – noting that limitations on activity and lifestyle may be of more immediate concern than living with the virus [Citation11]. In high HIV prevalence areas where access to treatment is now widespread, it is becoming increasingly important to consider the impact of these changes on service needs, including rehabilitation [Citation38,Citation39]. Despite mounting empirical evidence of the prevalence of both episodic and permanent disability among persons living with HIV and its subsequent impact on livelihoods and treatment adherence, there remains little evidence addressing the integration of rehabilitation into chronic HIV care [Citation31].

Rehabilitation approaches to living with disability start to appear increasingly relevant for people living with HIV [Citation40]. WHO guidance already acknowledges the need for rehabilitation in the context of living and aging with chronic HIV [Citation41]. Cross-sectional data from South Africa exploring the links between ART, disability and livelihoods underscore the need to better understand the rehabilitation needs of people on ART [Citation42,Citation43]. A growing evidence base is beginning to explore the role of rehabilitation in addressing the needs of adults and children living with HIV (e.g., [Citation44,Citation45]) but reviews emphasise that evidence is limited and more research is needed [Citation46,Citation47]. Providers and researchers recommend integrating rehabilitation approaches into HIV treatment care and support services, in order to address the disabling comorbidities of HIV and to make tangible improvements to life on ART; however, more evidence is needed to establish how to implement the service integration to improve access to care, improve communications and measure outcomes [Citation40,Citation48–50]. Strategies with the potential to address transport and access barriers and to confer physical and psychological benefits for people living with HIV and disability (especially in resource-poor settings where access to institution-based rehabilitation is limited) include home-based rehabilitation and task-shifting [Citation44,Citation51,Citation52].

Recognising the need to understand the complex environment of HIV programming for persons with disabilities from the dual perspectives of both potential users and service providers, the purpose of this exploratory study was to use a participatory approach to examine barriers and facilitators to access to HIV services for persons with disabilities, and hence to derive strategies for increasing access among this vulnerable group. This paper explores access to and use of HIV information and services among persons with disabilities in three sub-Saharan countries. Our findings from this study are intended to expand the evidence base for deriving strategies to ensure that HIV programs are accessible to persons with disabilities and to lay the groundwork for future research building on these findings.

Materials and methods

We conducted a multi-country exploratory situation analysis in Uganda, Zambia, and Ghana: three countries selected to exemplify different stages of HIV response to persons with disabilities [Citation33]. Uganda, where violence in the Northern regions has historically exposed the population to higher rates of physical disabilities and HIV infection, has a strong history of legislation, policy and programs supporting the rights of persons with disabilities and explicitly recognises in its NSP the need to develop services for persons living with HIV who experience disablement [Citation15,Citation53,Citation54]. The NSP for Zambia did not specifically identify disability as an issue, but nevertheless included indirect reference to disability within the HIV response [Citation55]. Despite identifying numerous specific vulnerable groups (including prisoners, cross-border traders, uniformed service personnel, fishermen), the NSP of Ghana avoided all mention of disability [Citation56].

In each of the three countries, assessment took place between September 2012 and February 2013 in the capital city (Kampala, Lusaka, Accra) and one peri-urban or rural site (Jinja, Solwezi, Amasaman) purposively identified through stakeholder discussions as a site with some pre-existing level of HIV programming for persons with disabilities. We focus on results from qualitative research methods, including key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) – participatory methods selected for their ability to promote inclusion and to accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities.

Advisory board

To guide this sensitive research and promote active, meaningful participation from persons with disabilities, we appointed an advisory board in each country with stakeholder representatives from national and local disabled persons’ organisations (DPOs). The advisory boards reviewed recruitment strategies and data collection instruments to make sure that they were ethical and appropriate, and also provided guidance on overall study design, results interpretation, and dissemination. Ethical approval bodies of the Population Council, the University of Zambia (UNZA), Ghana Health Services, The AIDS Support Organisation (TASO), and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology also approved study protocols and informed consent forms.

Research team and training

We worked closely with DPOs in each location to recruit field data collectors who were experienced in qualitative research methods, sensitive to the inclusion of persons with disabilities, and fluent in English and local languages. Our team included persons with disabilities actively participating in key roles, including a co-investigator, field staff and advisory board members. We conducted trainings for data collectors (interviewers and moderators) that addressed the ethical conduct of research and sensitisation to the needs of persons with disabilities, and provided opportunities for role-playing and enhancing skills in active listening and probing. During training, our team engaged in a participatory development process for the research guides to be used in interviews and focus groups, including confirming the consistent translation of specific technical terms into local languages (although written tools remained in English, which is widely spoken in all three countries).

Key informant interviews

Interviewers conducted a total of 21 KIIs with government officials (n = 2 each in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia) and service providers/program managers for HIV services (Ghana: 4; Uganda: 5; Zambia: 6) including national and local disabled persons organisations. We selected local DPOs based on initial recommendations from the national umbrella group for persons with disabilities and a continuing chain of referrals at the local level. Using semi-structured interview guides, our trained interviewers asked open-ended questions about stigma and discrimination, sexual and gender-based violence, health-seeking behaviours, and the inclusion and recognition of persons with disabilities in policies and programs. Each interview lasted approximately 1.5 h and was recorded, transcribed, and uploaded to a secure server within 24 h.

Focus group discussions

Moderators conducted a total of 44 FGDs among persons with disabilities (sensory, physical) and caregivers for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, stratified where possible by sex, location, type of disability, and HIV status disclosure, as shown in . Eligibility criteria for participation in the FGDs included those who were aged at least 18 years old and who self-identified with the group’s declared disability, caregiving and HIV status. At some locations, stratification by all characteristics was not possible due to small sample size; however, priority was given to maintaining separate groups by sex (except for caregiver groups), and to maintaining separate groups for persons with hearing impairment in order to facilitate communication. We recruited participants through DPO program managers and peer referral, and deliberately included both those who had recently accessed HIV services (prevention and treatment) and those who had not. We continued to iteratively identify new informants identified at each stage of the fieldwork through continuing referrals from staff and participants.

Table 1. Focus group discussions.

FGDs were conducted in central and disabled-accessible locations, including meeting rooms of DPOs. Moderators were all experienced at working among persons with disability, and FGDs among persons with hearing impairment included a sign interpreter. Prior to the start of each FGD, a researcher individually sought the informed consent of every potential participant in a private, confidential one-one conversation, documented in an accessible manner. Due to the sensitive nature of the discussions, the FGDs among females all had female moderators. For reasons of confidentiality, escorts and caregivers were asked to stay outside the interview room. All participants and escorts received reimbursement for time and transport.

Moderators used a discussion guide designed to elicit information about participant contact with HIV services, addressing barriers and facilitators to access and experiences of stigma and discrimination. FGDs lasted approximately 1.5 h and were conducted in the appropriate local language (or a mixture of languages). Interviews with the combined group for people with visual and physical disabilities tended to take slightly longer, due to the broader variety of concerns represented. The primary working language of the FGDs was English, but participants were free to contribute in whatever local language was most comfortable for them. FGDs were recorded, transcribed, and translated.

Data management and analysis

Field staff placed all FGDs transcripts and IDI field notes in a secure database accessible only by the Study Coordinator and the Principal Investigators, where all personal identifiers were immediately removed. We imported data into ATLAS.ti v5.2 (ATLAS.ti GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for analysis. We reviewed data and conducted analysis using a framework analysis approach [Citation57,Citation58]. We determined sample sizes for IDIs and FGDs based on the concept of saturation as well as a balance with resources to feasibly complete the task in all three countries [Citation59,Citation60]. We aimed for data triangulation by ensuring that we interviewed not just participants with disabilities but also staff of government agencies and DPOs. We developed codes iteratively using key domains outlined during research design, with additional codes added based on emergent themes. Code reports included markers for sex, disability, and location. Our core group of three analysts communicated frequently to discuss application of codes and check for consistency and to inductively identify emergent themes using a grounded theory approach [Citation57]. Each emergent theme thus inductively identified is a barrier or facilitator to accessing HIV services among persons with disabilities. Data interpretation continued iteratively during the analysis period through dialogue with in-country field staff and advisors. A 30% subsample of transcripts was double-coded for consistency checks. Findings presented in this paper are organised by theme, including illustrative quotes.

Results

Barrier: misconceptions about sexual activity among persons with disabilities

In all three countries, participants vociferously denied the common perception that people with disabilities do not have sex, or even any interest in sexual expression: a perception that commonly serves as a barrier to providing and accessing HIV services. An overwhelming majority of participants across all sites in all countries were emphatic in asserting that there was no truth to this frequently encountered perception, asserting that the feelings and emotions of persons with disabilities are just the same as everyone else. People with sensory and physical disabilities emphasised that they have the same feelings and desires for sex as everybody else: their emotions and most physical functions were not otherwise impaired.

It is not true that deaf do not have sex; I have feelings for sex just like hearing person. Some deaf friends were fighting over a girl. We are also hot and are humans. We only miss one sense of hearing, but our feelings are intact. (Male with hearing impairment, 26, urban Zambia)

Several participants drew self-deprecating comparisons with animals, reflecting negative external and internal perceptions of themselves and other disabled people. A woman with a physical disability in urban Ghana poignantly described an encounter in which she responded to the expressed curiosity of a woman without a disability about sexual activity among people with disabilities: “I told her, ‘excuse me, even the fowl has feelings, how much [more so] us?’” (Female with physical disability, 32, urban Ghana).

In all three countries, a minority of participants with physical disability acknowledged that there were some realistic practical limitations on sexual activity, depending upon individual circumstances. Nevertheless, FGD participants across all three countries suggested that perhaps there were reasons that people with disabilities might even be more sexually active than persons without disabilities. Male participants connected this assertion to enhanced virility and fertility. Female participants in settings as diverse as urban Uganda and rural Ghana observed that persons with disabilities may in fact be more engaged in sexual activity than others, albeit non-consensually, because they are in a less powerful position to choose their sexual partners and therefore face heightened exposure to abuse. Multiple participants reported experiences of exposure to abuse, associated with the assumption that all persons with disabilities must be HIV-negative because they have not had prior opportunities to become sexually active.

Most of the times when people are talking about HIV, most of us are never there. In that way, when a man who is not HIV negative meets a physically disabled woman, he thinks that she doesn’t involve herself in sexual intercourse and thus considers her free of HIV and vice versa. So this belief that disabled people are HIV free is dangerous. (Male with physical disability, 51, rural Uganda)

Even the able-bodied people look at people with disabilities as people who don’t get infected with HIV hence taking advantage. (Male with physical disability, age unspecified, urban Zambia)

Barrier: lack of information, misinformation and community beliefs

In all three countries, FGD participants reported that HIV information available to people with disabilities was disappointingly limited, and expressed frustrations with the limitations that they faced in accessing information. Comments from FGD participants in Zambia and Ghana reflected frustration with a lack of knowledge regarding HIV and sexual health. In comparison, comments from urban Uganda appeared to reflect a slightly higher level of awareness of HIV prevention and treatment, suggesting an emerging move towards recognition of the needs of persons with disabilities.

It is difficult to get information because no one speaks to us in the language that we understand, so it is a challenge. (Female with hearing impairment, 38, rural Zambia)

In the rural area, we don’t get any information about those things so we don’t know much about HIV or AIDS. Sometimes we hear the name AIDS, AIDS but we don’t know what it is. (Female with physical disability, 36, rural Ghana)

Moderators asked FGD participants to share with their group what facts they knew about HIV. The most commonly cited information was related to the possibility of sexual transmission and awareness of condom use for protection. Several participants mentioned vague awareness of the availability and limitations of treatment options, but acknowledged that their knowledge about HIV was limited. As discussions continued, participants revealed the prevalence of false and potentially dangerous beliefs about HIV transmission and prevention. For example, a participant in rural Ghana indicated a belief that the virus was airborne, and so had wide-ranging fears about contagion:

This type of sickness, it is either airborne or spiritual. If it is with you, it makes you behave as if you are mad. …. You do things when people see you; they insult you and call you names. It can disgrace you and can even cause you to die. Most often, this sickness [from HIV], the white man tried to treat it. I think, if you don’t pursue to get it treated, it can even cause you to die. (Male carer/uncle, 70, rural Ghana)

Misinformation was evident even among educated and prominent members of the community. A university-educated male with hearing impairment in rural Ghana, who had previously attended an HIV training workshop and subsequently assumed responsibilities for sharing HIV information among other people with hearing impairment, earnestly explained how he believed that that one of the modes of HIV transmission is via toilet seats.

Misinformation related to sociocultural and religious beliefs about HIV was common, especially in rural areas, where some participants described views commonly held in their communities associating HIV with witchcraft or Satanic rituals. Satanism has historically been a frequent accusation in Zambia, originally applied to interventions introduced by colonists and now still resonating with medical research (including ART) introduced by foreigners [Citation61].

Some say when you go to the clinic to get tested, the blood is for initiating us into Satanism. So people fear going to the health centre to get tested. (Female with physical disability, HIV-positive, 25, rural Zambia)

Further misinformation became apparent when discussing cultural beliefs towards disability: for example, a male caregiver in Uganda reported that he had encountered the perception that giving birth to a child with intellectual disabilities may be the result of HIV infection in the parent.

Despite being the targets of stigmatising attitudes themselves, persons with disabilities also exhibited their own stigmatising attitudes towards people with HIV – for example, people with visual impairment in urban Zambia and Uganda reported that signs of HIV infection are physically visible to an observer, so their visual impairment renders them unable to assess a potential partner for supposed indications of HIV infection.

The lack of sight by this blind person may prevent the person at least to seeing some of the visible signs, symptoms of HIV in an individual…. Being blind, you can’t see with your physical eyes some of the visible symptoms on this person’s body - but at least if you have sight, you can see some of these body signs [referring to HIV] and you’re able to tell, this person has a lot of sores on his face and mouth, and therefore conclude they might be [HIV] positive. (Female with visual impairment and physical disability, 30, urban Uganda)

Several FGD participants (most commonly, males in rural Ghana) shared perceptions of HIV that revealed associations with stigmatising, gender-discriminatory, and even potentially abusive consequences. Comments included descriptions of HIV as “a killer disease” associated with being “promiscuous” and the perception that “a bad girl” might transmit the virus to an “innocent” man. An HIV-positive male asserted “You cannot avoid having sexual intercourse with a lady wearing mini skirt” (Male with hearing impairment, 20, HIV positive).

Recognising the limitations of their own knowledge about HIV, persons with disabilities participating in the FGDs expressed eagerness for more information about HIV. Participants identified activities that would help them to learn more about HIV and how to address its consequences within their own lives, including community meetings, workshops, and dramas, and door-to-door sensitisation campaigns. A participant in rural Uganda acknowledged the importance of working with local community leaders to address misleading cultural beliefs. Participants voiced particular concern about the need to reach out to rural areas with community-based HIV education activities.

Barrier: literacy challenges

Participants described how literacy challenges obstruct the delivery of information and the active engagement of persons with disabilities in HIV programs. Especially in Ghana, they discussed the linkages between disability and illiteracy as a barrier to accessing HIV information, and particularly in rural areas. Participants indicated that persons with disabilities may have been unable to attend school and may be unable to read; for participants who were deaf, their disability had undermined not only their ability to access verbal information about HIV (e.g., public education broadcasts on TV) but also written information. They expressed demand for the inclusion of sign language in public education TV.

In a family, if there is a deaf child, it experiences more oppression and families favour hearing children. The parents will say it is costly to take the deaf child to school. That it is better to support able-bodied children, that is abuse and the deaf would not succeed in life. (Male with hearing impairment, HIV positive, 48, urban Zambia)

Other participants reported that they had been unable to understand educational materials that used unfamiliar technical terms, and would have preferred the use of simpler, more accessible language.

I think the main issue is most of us are not mainly educated, so these words when they are mentioned, if you don’t get someone to explain it to you, then you are lost. You hear there is this disease STDs but you don’t know what the disease is. (Female with physical disability, 23, rural Ghana)

Facing the simultaneous challenges of being deaf and also unable to read, participants reported that service providers were struggling to find an appropriate mode of communication with people who are deaf.

I happen to meet one deaf illiterate at the hospital. … I saw the doctor trying to communicate by writing to this deaf illiterate. He was not understanding. So I told the doctor, I wrote to the doctor, “This guy is an illiterate, he cannot read or write, so I think I can help her”. …So if I was not around, what will happen to this deaf person? (Female with hearing impairment, 26, urban Ghana)

FGD participants indicated a need for developing information and publicity materials tailored to meet the needs and daily realities of people with specific disabilities, utilising technologies and other innovative approaches. While some participants indicated the importance of print media (including newspapers, magazines, leaflets, brochures) in spreading information about HIV, others highlighted the need for improved visuals and translation of such materials into Braille, large-print, audio and pictorial versions. Others (in Uganda and Ghana) suggested the exploration of new media outlets including internet and mobile phone technology for sharing such information, and emphasising technology access through schools. Key informants reiterated the need for sufficient funding to cover such initiatives, and observed that resources currently allocated for such measures to promote accessibility were insufficient.

Barrier: vulnerability to abuse

Participants from all locations described how persons with disabilities are vulnerable to sexual, physical, verbal, and emotional abuse and to exploitation through work tasks. They described how a lack of physical strength, communication barriers, and poverty rendered them at elevated risk of sexual violence, including rape (especially as they were perceived to be sexually inactive and hence free of HIV infection – see above); and a lack of empowerment to bring the perpetrator to justice. Some participants felt that they could not rely upon family and community for support, yet they felt especially vulnerable when doing daily tasks alone, such as fetching water.

Most of the men disrespect us. They force us into having sex even when we don’t want. They know that we can’t take off. You may think it is disabled people who make us pregnant, no! It is these normal men, don’t look at a woman on the streets and think that she just gets babies because she wants, she is forced. And even if you report to the LC [local council authority], you find that these men bribed them so you are left helpless. (Female with physical disability, HIV positive, 30, urban Uganda)

Disabled people are at a higher risk because we are more vulnerable to rape as we are not strong enough to defend ourselves. (Female with physical disability, 28, rural Zambia)

Us the deaf are at higher risk because we are used unknowingly. We keep silent - but for the people who are not deaf, they can scream and people will hear them. (Female with hearing impairment, 43, rural Zambia)

The risk for we the disabled, especially let’s say our women because of the disability – we don’t have work to do. So a man can call the woman, “I will give you money, I will give you money”, and she will have sex with him so that do whatever he pleases with her. (Male with physical disability, HIV positive, 48, rural Ghana)

Parents and caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities acknowledged that their children are especially vulnerable to sexual exploitation and abuse.

The intellectually disabled people are easily convinced to have sex with because they are unable to reason properly. (Female carer/mother, 51, rural Zambia)

It should also be noted that some men have a tendency of saying people with intellectual/developmental disability can be played with sexually because they are not normal. (Female carer/sister, 18, urban Zambia)

Discussions among parents and caregivers focussed upon the need to safeguard against abuse and exploitation, and also to respond appropriately to it when it happens. Their conversations highlighted the complex and often contradictory roles and responsibilities of parents and guardians of children with all kinds of disabilities. Some caregivers were able to recognise that the person in their care might have desires for which they seek fulfilment by engaging in sexual relationships or even marriage, and that denying these needs increased vulnerability to abuse, leaving them out of reach of healthcare services. These caregivers emphasised that they had an important role to play in facilitating access to information among their disabled children who otherwise might not be able to access it directly themselves. However, other caregivers indicated that caregivers themselves might act as a deliberate barrier to their children’s information, due to a reluctance to acknowledge sexual activity.

Barrier: complexity of stigma across multiple layers

Participant comments revealed multiple overlapping experiences of stigma among persons with disabilities, including internalised self-stigma, stigmatising attitudes in the community towards people with disabilities, stigmatising attitudes towards people with HIV, and further stigma associated with gender, pregnancy, and abuse.

Internalised stigma

Participant comments reflected a high level of internalised stigma and negative self-perceptions among persons with disabilities. Manifesting in negative attitudes and low self-esteem, internalised stigma related to their disability appears to be associated with elevated vulnerability to HIV infection and reluctance to seek HIV testing, due to fears of compounding the stigma already experienced due to disability.

Stigma due to disability

Participants expressed that they often felt stigmatised in the community by virtue of their disability, resulting in their positive attributes being overlooked. Furthermore, they were cognisant that the social and physical isolation arising from the stigma associated with their disability marginalised them and prevented them from accessing information about HIV through the usual channels. Male and female participants from all three countries consistently indicated that persons with disabilities are at elevated risk of HIV infection because of the lack of deliberate choice in their sexual opportunities. When propositioned by someone apparently offering intimacy and affection, they said that persons with disabilities may lack confidence or self-esteem, so that they may be perceived as less fussy or discriminating about the person with whom they choose to enter into a sexual relationship, indicating that they have less power to negotiate or refuse the relationship.

The risk here is that we the deaf people are more vulnerable, reason being we do not have choice or chance to get the real partners we want. For example, I got infected simply because I had no choice to choose the real man. So during that time, whoever came, I had sex with him. … Most deaf people just have sex with anyone who comes because they think that’s their only chance to get a partner and in that process they end up being infected. (Female with hearing impairment, HIV positive, 34, urban Uganda)

Compounded stigma of disability and HIV

Among the participants who identified as both HIV-positive and having a disability, an overwhelming majority (68 out of 70) indicated that their disability had pre-dated their HIV-positive status. Most of these participants had been grappling with the impacts of stigma and exclusion long before they became HIV positive. Yet, they spoke of the multiple interlinked ways in which the stigma of HIV and the stigma of disability had both become manifest in their own lives. They described discrimination and stigmatising behaviours from within families and communities, and struggling with a need for keeping their HIV status secret, especially within a community that had not even been able to acknowledge the possibility of their sexual activity.

It is assumed that the HIV, you will get it through sexual intercourse, and already for me I have a big stigma, so if they are going to do this thing [HIV test] and you will say I want to go and do some, they will say ‘eh, these people’ [claps]. So for me, I have not made the attempt to go and do it, so that I will get second stigma [laughter]. (Female with visual impairment, 45, urban Ghana)

Already the blind, many people do not want to come nearer. Now you go and test this thing [HIV] and you come, maybe they say you have got it [laughter], you have worsened the case. (Male with visual impairment, 54, urban Ghana)

Additional stigma of gender, pregnancy, and abuse

Participants reported that women with disabilities face additional challenges to accessing services because healthcare providers expressed views representing traditional gender norms regarding their role and movements outside the home. Women with disabilities encountered surprise and even hostility during pregnancy, representing yet an additional layer of stigma and further barriers and discouragements to service access. People who had been abused faced a further layer of internal trauma and external stigma.

These are things that I have heard from people with disabilities, where a nurse or medical personnel would say “you don’t even feel sorry for yourself to go and get pregnant, your husband, how cruel can he be to make you pregnant and who is this man who made you pregnant?” Does it mean that a person with disabilities does not have sexual feelings? They do have sexual feelings. So that’s the social stigma that I am looking at, that if a person with disabilities were to walk into a VCT centre, the first thing people would say “this person, where can they get AIDS from? Who would even want to have sex with these people?” So you see, that is the stigma; there is always ‘these people’ connotation that is attached to persons with disabilities, especially those disabilities that can be seen, like blindness and physical disabilities. (Male, DPO Program manager, urban Zambia)

It has happened that some deaf women are raped and that traumatises them. You find that they will just be sitting lonely because they don’t know how to report or how to solve the problem because of communication barrier. Others are afraid thinking friends will laugh at them that they are victims of rape. (Female with hearing impairment, 19,urban Zambia)

Barrier: attitudes among service providers

We report elsewhere [Citation62] on practical barriers to access that make the process of seeking healthcare services more burdensome for persons with disabilities, including the frequent repeat clinic visits required for maintaining ART; such as physical infrastructure (transport to clinic, access ramps), accessible information materials, and the need for sign language interpreters. Just as discouraging are the human barriers to seeking services: participants reported the need for a fundamental shift in attitudes among healthcare providers towards persons with disabilities, based on their experiences of demeaning and offensive interactions. They asserted that service providers need training to improve empathy and communications skills, e.g., recognising that the prospect of adding the stigma of HIV positive status to existing stigma already associated with disability heightens client fear of the HIV test result; acknowledging the specific obstacles to HIV testing that a physically disabled person has already overcome just by getting inside the door of an HIV clinic. However, participants in all three countries reported some examples of providers whose attitudes and practices were beginning to show signs of change, possibly following exposure to sensitivity training.

People with visual impairment in particular reported impatient and disrespectful responses among healthcare providers to whom they had expressed concerns; for example, when expressing fear about an injection whose source they could not verify by observation. Other participants with visual impairment in Ghana expressed feelings of elevated vulnerability to HIV transmission through casual contact with blood and shared blades outside of the healthcare service provision environment, including instruments used for personal grooming tasks for which they are dependent on caregivers for assistance (e.g., cutting hair and nails).

Sometimes we can’t see the injection they are injecting you with, sometimes when we go to the hospital, the nurses and the doctors become annoyed with us because we always want to question and know what exactly you are using so they become annoyed with us, so sometimes they don’t have patience for us, some of the nurses don’t have patience for us, they can pull you here and there and inject you anyhow, sometimes shout on you “So if you are blind, are you also deaf, can’t you hear what I am saying?” So sometimes those people can also lead you to sickness, that is the most important place you should tackle. (Male with visual impairment, 39, rural Ghana)

We acknowledge that, consistent with the literature (e.g., [Citation27]), a minority of participants nevertheless also reported some incidences of experiencing disability as an advantage within healthcare facilities. They emphasised the importance of cultivating relationships with specific providers in order to encourage sympathetic personal treatment.

Every time I get to the hospital I feel special, you should see the way, you know with my disability and all that, someone comes along with a wheel chair helps me get on it and engage me in a conversation its encouraging. (Female with physical disability, HIV positive, 48, urban Ghana)

When you conceive you need to get in touch with one person or somebody to work on you, you befriend him or her, you can get good services…. You have to first work, look around for the doctor talk to him or her and befriend him or her and then they can attend to you, a person who could care for you during antenatal and up to the time when you deliver. (Female with hearing impairment, age unspecified, urban Uganda)

Facilitator: participatory responses to stigma

Participants suggested multiple practical responses to addressing the manifestations of stigmatising attitudes towards and among persons with disabilities that combine to impede access to and utilisation of HIV services. They expressed a desire for increased sensitisation activities in the community to address both issues of HIV and disability, employing messages relevant for persons with and without disabilities, including the importance of sharing responsibility, promoting peer leadership, and increasing the active and visible participation of persons with disabilities in intervention activities.

Peer leadership

Participants emphasised the importance of peer communication and visibility of people living openly with HIV as role models and inspiration. Persons with disabilities who are living with HIV were sought as role models to come out publicly and educate others. FGD participants suggested promoting the active and visible participation of persons with disabilities into clinic outreach activities and healthcare provider training, for example, employing persons with disabilities as counsellors, peer educators, and trainers. In particular, people who were deaf were keen to promote the specific participation of those who were also deaf in appropriately communicating HIV information to other deaf people, and requested specialised outreach and training in order to prepare deaf people to step up into taking such roles.

The people without disability think we are totally disabled, yet there are some things we can do. For example, you can find a lame woman or man who’s better than a person without disability… we should take responsibility of helping each other. …The more we hide ourselves, the more we shall get sick and keep on spreading the disease to others. (Male with physical disability, HIV positive, 38, urban Uganda)

I think we living with HIV also have a role to play; we have to conscientise our people about it. (Female with physical disability, HIV positive, 48, urban Ghana)

What I would like to see is for people with disabilities to be able to teach others including teaching the able-bodied so that we at least see that we are all moving at the same level in terms of knowledge on HIV. Not just seeing able-bodied teaching the disabled. Amongst us people with disabilities, there are people who are able to teach. (Male with physical disability, 29, urban Zambia)

They should also employ some of the physically challenged and the visually impaired person to their hospital because sometimes who knows it, feels it.… So if they can provide that chances for us to do nursing and the like, it can help. (Female with visual impairment, 26, rural Ghana)

National leadership and entertainment

Several FGD participants indicated that their knowledge and awareness of HIV had been greatly influenced by local and national leadership speaking out. Uganda’s President Museveni in particular was credited as having had an important influence in “contributing much to fight the disease” (Male with physical disability, 22, rural Uganda). Participants talked about the influential role of musicians such as Philly Bongole Lutaaya (Uganda) and the Sakala Brothers (Zambia) in spreading an HIV awareness message through music accessible throughout the community and including people with disabilities. Deaf participants emphasised that music, dance and drama activities in the community can be made accessible to those “who use eyes to get the information” (Male with hearing impairment, 24, urban Uganda). FGD participants proposed that organisers of public events (e.g., social and life-cycle events, parent–teacher association meetings) should include education messages about HIV in order to reach people with disabilities within the audience.

People with disabilities should be included in every aspect of government in regards to information about HIV. People with disabilities should have equal information on HIV as the people who are able-bodied. For instance, if there is a workshop on HIV, people with disabilities should participate together with the able-bodied people so that they are able to disseminate information to their colleagues. (Male with physical disability, 34, rural Zambia)

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this paper, we have identified several important contributions to the evidence base, and we have worked with in-country stakeholders to use them as a solid basis for identifying recommendations to improve access to HIV services among people with disabilities. Our findings point towards practical steps towards improving service accessibility and utilisation, particularly emphasising the power of community responsibility and support.

Access to information

The damaging assumption that persons with disabilities are not sexually active simultaneously fails to acknowledge the human right to health and also heightens existing vulnerabilities to sexual exploitation and abuse, especially among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. HIV education campaigns must make it an urgent priority to undermine and invalidate these harmful myths and other sources of misinformation prevalent among persons with disabilities and among the community at large. For example, the stigmatising belief expressed by blind people in this study that an observer can visually judge HIV status may be a result of social isolation or lack of access to information. This is consistent with a qualitative study exploring access to healthcare among blind people in Kampala that noted a reliance on other people for accessing health information [Citation26]. Strengthening HIV education outreach to meet the needs of persons with disabilities living in rural areas is urgently required, addressing the association with illiteracy to make sure that information is accessible to people of all levels of education. Community interventions targeted through schools and religious groups, while potentially powerful methods of outreach, must recognise that many persons with disabilities are excluded from school and community activities, and find alternative means to reach out to those who are socially isolated due to disability, such as outreach and home-based programs.

Compounded stigma

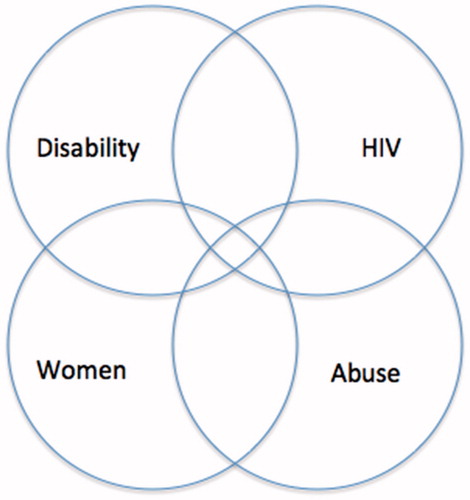

Results from this three-country study show that – across settings and disability types – manifestations of stigma consistently constitute major barriers to the utilisation of HIV prevention and treatment services by persons with disabilities. illustrates the multiple overlapping layers of stigma that compound each other to result in social isolation, impeding access to HIV information and services. Self-stigma among persons with disabilities internalising negative perceptions about their disability can lead to a lack of self-confidence, increasing vulnerability to HIV and serving as an impediment to utilising services, delaying access to testing and treatment, and must be addressed through interventions to boost self-esteem. Among study participants who were both disabled and HIV-positive, most had been disabled long before they became HIV positive, and had lived with the stigma of disability long before experiencing the stigma of HIV. Among these people, the stigma of disability has set the stage for hyper-awareness and fear of further reasons for stigma and exclusion. Fears of the combined stigma of HIV and disability together has led to reluctance to get tested for HIV and find out about subsequent treatment options. Among women, these stigmas may be compounded by a further overlapping layer, as experienced through gender-related vulnerabilities to pregnancy, abuse, financial dependency, inequitable gender norms, and access to health services. Experiences of abuse and exploitation, to which persons with disabilities are especially vulnerable, add a further layer of stigma. Though many of these barriers are also present for people without disabilities, they are evidently elevated among persons with disabilities due to compounding of multiple stigmas and vulnerabilities.

Attitudinal barriers

Consistent with other research (e.g., [Citation63]), this study has identified some powerful barriers impeding access to HIV information and services for persons with disabilities. In particular, this study has clearly identified some risky attitudes towards and among persons with disabilities and has illustrated ways in which stigma exacerbates the limited access to and utilisation of services. We found evidence of stigmatising attitudes in all three countries, however, positive interactions were more often reported in settings in which sensitisation and intervention activities had already been initiated, especially Uganda and urban Zambia.

Research has frequently emphasised the importance of addressing issues of physical infrastructure to aid communication and mobility at healthcare facilities (e.g., access ramps, Braille materials, sign language translation) [Citation62]. However, we note from this study that fundamental and far-reaching change in attitudes is also needed at clinics to meet the needs of persons with disabilities: that is, sensitivity training to improve the skills of healthcare providers. Sensitising healthcare providers to raise awareness of the risks, rights and needs of persons with disabilities is critical to increasing their access and utilisation of HIV services. For example, HIV counsellors must learn how to provide nuanced counselling services recognising the specific issues of HIV and disability manifest simultaneously; community health workers must learn how to teach a blind person how to use a condom; pharmacists must learn how to discuss ARV treatment regimens with people who are unable to read their prescription or who cannot easily hear instructions given verbally; nurses must learn how to address and reassure when they are administering an injection to someone who feels especially vulnerable because they cannot see the process; counsellors must consider how to discuss HIV risk and testing with people who have intellectual and developmental disabilities and their caregivers, recognising that parents can either be important conduits for information or occasionally a barrier. Training should additionally recognise the sexual and reproductive health needs and vulnerabilities of women with disabilities, including during pregnancy.

Participatory responses

Our research has indicated the potential value of participatory and inclusive approaches in addressing the obstacles to accessing HIV services for persons with disabilities and suggests some starting points for implementation. We underscore the need to increase meaningful, visible, active roles for persons with disabilities in designing and implementing inclusive HIV intervention activities, including promoting peer participation among persons with disabilities to develop and delivery HIV education and outreach messaging. Community-based interventions to address stigmatising attitudes and discriminatory actions should employ strategies of peer support and leadership from persons with disabilities to address deep-seated cultural beliefs and prevent harmful myths from spreading; simultaneously recognising the need for family and community support among persons with disabilities, and addressing the circumstances when it is lacking.

General and targeted communications

We recognise the need for making general HIV education campaigns more accessible to persons with disabilities, and also the need to design specifically targeted approaches for those who are excluded from such public outreach activities. Communications campaigns (e.g., to encourage the uptake of testing and treatment services) can boost accessibility to persons with disability by promoting the active involvement of persons with disabilities as spokespeople and leaders who accurately reflect their lived experiences. Campaigns providing education about HIV at local and national levels through multiple channels (including political, musical, creative) should take care to design communications to be accessible to persons with disabilities: for example, augmenting campaigns that rely upon written materials with additional versions in visually accessible formats, including Braille, large print, and pictorial editions; adding sign language interpreters and/or captioning to television broadcasts; addressing the physical accessibility of locations for music and drama events. New electronic media increasingly offer new outreach opportunities where technologically feasible and appropriate, but require continuing attention to ensure that communications are relevant to persons with disabilities, e.g., reflecting the lived experiences of persons with disabilities who are sexually active; addressing the combined effects of multiple layers of stigma experienced by people who are disabled as well as living with HIV.

Examples of more targeted intervention approaches aimed at reaching persons living with disabilities include developing HIV education messaging for persons with intellectual disabilities and their caregivers through delicate and sensitive collaboration with community representatives, designed to recognise the varieties of individual circumstances and the complex roles of parents and caregivers. The frank and lively discussions of sensitive topics in this study suggest the possibility of creating safe spaces in which persons with disabilities (especially women) can openly discuss HIV-related issues to ask questions and access information.

Role of political will

We have seen that vocal leadership by respected figures in the political and popular entertainment spheres provides the opportunity to build public support for recognising and addressing the heightened vulnerability of people with disability to HIV. Crucial to ensuring long-term sustainable change is the need to address political will through the NSP for HIV. Such initiatives have started in Uganda, where persons with disabilities are already formally recognised in the NSP as “key populations” vulnerable to HIV, but wider recognition will be needed in order to give rise to policies and programs that operationalise this priority at the local level [Citation54,Citation64]. A new version of the NSP for Ghana briefly acknowledges the role of disability in vulnerability [Citation65]. Questions about disability have recently become available for optional inclusion in the national Demographic and Health Surveys and will certainly aid the development of future data sources – Uganda was recently among the first countries to deploy the disability module, enabling the recognition of persons with disabilities and integration with HIV data [Citation7]. Especially in countries that have ratified the CRPD, national governments, international agencies and funders have an opportunity to promote inclusive HIV programming [Citation15], for example, by making HIV program funding conditional on accessibility and inclusivity to persons with disabilities.

Need for high quality evidence

Although the reviews cited earlier [Citation9,Citation11,Citation12] included multiple empirical studies employing various designs to explore different research questions addressing the relationships between HIV and disability, they were unable to locate a single study providing direct population-based HIV prevalence data in sub-Saharan Africa comparing persons with and without disabilities. It was not until 2017 that such a study was published, employing a matched control group and probability-based sampling [Citation13]. This milestone study showed that persons with disabilities have higher prevalence of HIV infection and higher risk of sexual violence than people without disabilities, and documents stronger correlations between HIV infection and sexual risk among persons with disabilities than the control group. While the existing body of primarily qualitative research is undoubtedly valuable for exploring the obstacles and vulnerabilities experienced by persons with disabilities, without rigorous epidemiological data to inform policy development, it seems likely that persons with disabilities will continue to be overlooked from national HIV strategies for prevention, care and treatment – and consequently, from programmatic interventions. Thus, we reiterate the need to build the evidence base on the intersections between HIV and disability by focussing on intervention research that will provide tangible answers to pragmatic questions about how to deliver accessible services. It remains crucial to prioritise the inclusion of persons with disabilities at every stage of research (from study design through interpretation and dissemination) and the ability to disaggregate data by disability type (rather than treating “disability” alone as a single homogenous category), both of which are required to improve data quality, rigour and usefulness [Citation66]. High-quality research utilising both qualitative and quantitative methodologies will remain a valuable tool to describe the attitudes and experiences of persons with disabilities in accessing HIV services and in addressing the formidable obstacles to prevention, treatment, care and support. In order to reach the ambitious policy goals of 90–90–90 [Citation32], an evidence-based programmatic approach is needed to recognise the intersecting vulnerabilities at work, in order to drive a continuing response that will make services more comprehensive and equitable.

Study limitations

We recognise the practical limitations of this study, which was deliberately designed as an exploratory situation analysis to provide preliminary information about a complex, nuanced and under-researched topic, in order to generate data that would inform the design of future research, as well as to contribute towards evidence-based programmatic actions and policy decisions. We acknowledge the following limitations to our study design in order to point out our recommendations for the design of future research studies on this topic, which will build and improve upon our preliminary findings.

Due to necessary practical limitations, we had no comparison group through which to contextualise attitudes among persons with disabilities within the prevailing knowledge and attitudes of their communities; we were unable to ask questions about extremely stigmatised behaviours (e.g., drug use, men who have sex with men); and we were unable to look beyond the restrictions of the three main categories of physical, sensory and developmental disability towards other socially stigmatised conditions (e.g., albinism, epilepsy) [Citation9]. Furthermore, due to practical limitations, our discussion groupings brought together persons with visual and physical disabilities, while a more sensitive approach might have separated these groups to encourage freedom of expression and data disaggregation. We further acknowledge the lack of direct individual participation from people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, whose interests were indirectly represented in this study by their caregivers. A growing body of research and practical guidance discusses the direct inclusion of people with learning disabilities in participatory qualitative research to promote their social inclusion and accurately reflect their views [Citation67–70]. With careful training and preparation, FGDs can indeed provide a valuable way to recognise and include the opinions of adults with learning disabilities; however, skilled facilitation is required to address individual needs (e.g., communication, attention/concentration, mental fatigue), manage group interactions, and to interpret data thus elicited. Promoting the participation of these extremely vulnerable people must be done with great sensitivity to ensuring their protection, and was unfortunately not possible in the setting of this relatively small and rapid study.

Conclusions

In an era in which information about HIV is frequently presumed ubiquitous, especially in high-prevalence settings, it is disturbing to read comments from persons with disabilities indicating lack of awareness about HIV and frustration about a lack of access to HIV information and services. Consistent with other research (e.g., [Citation9,Citation18]), this study indicates that persons with disability still have very limited knowledge about HIV. In fact, some comments from study participants are reminiscent of opinions expressed during much earlier stages of the HIV epidemic, prior to the advent widespread public education campaigns promoting HIV prevention messaging, including the widespread acceptance of false and stigmatising beliefs and reliance on cultural perceptions. Persons with disabilities are frequently excluded from mainstream communication channels, including public media broadcasting and general social discourse, resulting in a “time-warp” that has left them years behind their non-disabled counterparts in terms of HIV awareness. Nevertheless, this study has revealed that persons with disabilities are eager to learn more about HIV and how they can protect themselves.

The complex two-way relationship between HIV and disability is poorly understood: i.e., people with disability are vulnerable to HIV infection; people with HIV are increasingly becoming disabled. In this study, we have focussed on the vulnerability of persons with disabilities to risks of HIV infection. As access to ART expands and people live longer with HIV, we must acknowledge the implications of the links running in the opposite direction. In particular, as persons living on HIV treatment increasingly experience disability and live longer with both permanent and episodic disabilities, demand grows to broaden HIV services to address these emerging disabilities through rehabilitation services.

The multiple overlapping vulnerabilities of disability and HIV are not coincidental. Some of the greatest obstacles faced by persons with disabilities include social inequalities, poverty, lack of access to education and health services, and human rights violation: all of which are factors that simultaneously increase vulnerability to HIV infection [Citation10]. Yet, despite a growing evidence base documenting these two-way and multi-dimensional linkages, persons with disabilities continue to be overlooked by HIV services (including HIV prevention education, testing, treatment, care and support) and persons living with HIV continue to struggle to address their ongoing disability-related needs (including rehabilitation services). The interconnectedness of these healthcare challenges and their resulting impacts on wellbeing and inclusion (e.g., [Citation34,Citation71]) point towards the value of a holistic programmatic response that recognises the real risks, needs and preferences of people facing the intertwined challenges of HIV and disability. In order to promote real and lasting change, interventions must be designed to look beyond the immediate service delivery context and take into account the living circumstances of individuals and communities affected by HIV and disability.

Acknowledgements

We express our deepest thanks to the study participants who so generously and thoughtfully gave of their time and efforts to participate, and without whom this research study could not have taken place. We acknowledge the collaborating institutions and their staff for their active involvement in the design and implementation of this study, including participation on the Advisory Board; in particular Rita Kyeremaa Kusi (Ghana Federation of Disability Organisations, formerly Ghana Federation of the Disabled); Yaw Ofori-Debrah (Ghana Association of the Blind); Lilian Bruce-Lyle (Ghana Society of the Physically Disabled); Kofie Humphrey (Mental Health Society of Ghana); Emmanuel Larbi (Ghana AIDS Commission); Rose Acayo, Atwijukire Justus, Edson Ngirabakunzi (National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda); Robinah Alamboi (Mental Health Uganda); Felix Mutale (Zambia Agency for Persons with Disabilities); Sylverster Katontoka (Mental Health Users Network of Zambia); and Malika Sakala (Zambia Federation of Disability Organisations). We are also grateful for the contributions of study coordinators Grimond Moono (Zambia), Steven Teguzibirwa (Uganda), Hilary Asiah and Selina Esantsi (Ghana) and their data collection teams. Thanks to Population Council colleagues for significant technical and practical support, including Sherry Hutchinson, Sam Kalibala and Naomi Rutenberg. The authors’ views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Disclosure statement

The authors’ views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Frontera WR. The world report on disability. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:549.

- Mulindwa IN. Study on reproductive health and HIV/AIDS among persons with disabilities in Kampala, Katakwi and Rakai Districts [Internet]. Kampala, Uganda: Disabled Women’s Network and Resource Organisation; 2003 [cited 2017 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.aidsfreeworld.org/Our-Issues/Disability/∼/media/Files/Disability/Disability%20Study%20from%20Kampala.pdf

- Trani J-F, Browne J, Kett M, et al. Access to health care, reproductive health and disability: a large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1477–1489.

- Umoren AM, Adejumo AO. Role of sexual risk behaviors and sexual attitude in perceived HIV vulnerability among youths with disabilities in two Nigerian cities. Sex Disabil. 2014;32:323–334.

- Taegtmeyer M, Hightower A, Opiyo W, et al. A peer-led HIV counselling and testing programme for the deaf in Kenya. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:508–514.

- Touko A, Mboua CP, Tohmuntain PM, et al. Sexual vulnerability and HIV seroprevalence among the deaf and hearing impaired in Cameroon. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:5.

- Abimanyi-Ochom J, Mannan H, Groce NE, et al. HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of persons with and without disabilities from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011: differential access to HIV/AIDS information and services. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174877.

- Olaleye AO, Anoemuah OA, Ladipo OA, et al. Sexual behaviours and reproductive health knowledge among in-school young people with disabilities in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Educ. 2007;107:208–218.

- Hanass-Hancock J. Disability and HIV/AIDS—a systematic review of literature on Africa. JIAS. 2009;12:34.

- Rohleder P, Braathen SH, Swartz L, et al. HIV/AIDS and disability in Southern Africa: a review of relevant literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:51–59.

- Banks LM, Zuurmond M, Ferrand R, et al. The relationship between HIV and prevalence of disabilities in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review (FA). Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:411–429.

- De Beaudrap P, Mac-Seing M, Pasquier E. Disability and HIV: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of the risk of HIV infection among adults with disabilities in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1467–1476.

- De Beaudrap P, Beninguisse G, Pasquier E, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection among people with disabilities: a population-based observational study in Yaoundé, Cameroon (HandiVIH). Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e161–e168.

- Groce N. HIV/AIDS and disability: capturing hidden voices: the World Bank/Yale University global survey on HIV/AIDS and disability [Internet]. World Bank: Washington, US; 2004 [cited 2017 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/main?pagePK=64193027&piPK=64187937&theSitePK=523679&menuPK=64187510&searchMenuPK=57313&theSitePK=523679&entityID=000090341_20051114161514

- Shome S, Tataryn M. People with disabilities and the AIDS pandemic: making the e link. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2008;13:75–76.

- Kvam MH, Braathen SH. “I thought … maybe this is my chance”: sexual abuse against girls and women with disabilities in Malawi. Sex Abuse J Res Treat. 2008;20:5–24.

- Philander JH, Swartz L. Needs, barriers, and concerns regarding HIV prevention among South Africans with visual impairments: a key informant study. Research reports. J Vis Impair Blind. 2006;100:111–114.

- Aderemi TJ, Pillay BJ, Esterhuizen TM. Differences in HIV knowledge and sexual practices of learners with intellectual disabilities and non-disabled learners in Nigeria. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:17331.

- Chireshe R, Rutondoki EN, Ojwang P. Perceptions of the availability and effectiveness of HIV/AIDS awareness and intervention programmes by people with disabilities in Uganda. Sahara J. 2010;7:17–23.

- Eide AH, Schür C, Ranchod C, et al. Disabled persons' knowledge of HIV prevention and access to health care prevention services in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1595–1601.

- Rohleder P, Eide AH, Swartz L, et al. Gender differences in HIV knowledge and unsafe sexual behaviours among disabled people in South Africa. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:605.

- Yousafzai A, Edwards K. Double burden: a situation analysis of HIV/AIDS and young people with disabilities in Rwanda and Uganda. London: Save the Children; 2004.

- Wells J, Clark K, Sarno K. An interactive multimedia program to prevent HIV transmission in men with intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;119:276–286.

- de Reus L, Hanass-Hancock J, Henken S, et al. Challenges in providing HIV and sexuality education to learners with disabilities in South Africa: the voice of educators. Sex Educ. 2015;15:333–347.

- Nixon SA, Cameron C, Hanass-Hancock J, et al. Perceptions of HIV-related health services in Zambia for people with disabilities who are HIV-positive. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18806.

- Saulo B, Walakira E, Darj E. Access to healthcare for disabled persons. How are blind people reached by HIV services? Sex Reprod Healthc. 2012;3:49–53.

- Parsons JA, Bond VA, Nixon SA. ‘Are We Not Human?’ Stories of stigma, disability and HIV from Lusaka, Zambia and their implications for access to health services? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127392.

- Kampala Declaration on Disability and HIV & AIDS [Internet]; 2008. Available from: http://www.dhatregional.org/docs/kampala_declaration_hivaids_disability%5B1%5D.pdf. http://africacampaign.december.fr/uploads/media/kampala_declaration_on_disability_and_hiv_aids_01.pdf9

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Internet]; 2008; [cited 2015 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml

- Hanass-Hancock J, Grant C, Strode A. Disability rights in the context of HIV and AIDS: a critical review of nineteen Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) countries. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2184–2191.