Abstract

Purpose: At least 5% of people in Australia and the USA have cognitive impairment and require support for decision-making. This paper details a research program whereby an evidence-based Support for Decision Making Practice Framework has been developed for those who support people with cognitive disabilities to make their own decisions across life domains.

Methods: The La Trobe framework was derived from a research program modeled on the Medical Research Council four-phase approach to development and evaluation of complex interventions. We completed phase one (development) by: (1) systematically reviewing peer-reviewed literature; and (2) undertaking qualitative exploration of the experience of support for decision-making from the perspectives of people with cognitive disabilities and their supporters through seven grounded theory studies. Results of phase two (feasibility and piloting) involving direct support workers and health professionals supported phase three (evaluation) and four (implementation), currently underway.

Results: The framework outlines the steps, principles, and strategies involved in support for decision-making. It focuses on understanding the will and preferences of people with cognitive disabilities and guides those who provide support including families, support workers, guardians, and health professionals.

Conclusions: This framework applies across diverse contemporary contexts and is the first evidence-based guide to support for decision-making.

Support for decision-making is essential to maximise the participation of people with cognitive disability in decisions about their lives.

Research has shown that support for decision making is a complex multifaceted process comprising multiple overlapping steps, delivered through individually tailored strategies and informed by practice principles.

The La Trobe practice framework provides an evidence-based guide for engaging in effective support for decision-making with people with cognitive disability.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

At least 650 million people or 10% of the world’s population have some form of disability [Citation1]. A substantial proportion of these people have cognitive disability due to a variety of developmental conditions affecting various intellectual or cognitive functions, including intellectual disability, specific conditions (such as specific learning disability, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), and problems acquired in adulthood or later in life through acquired brain injuries (ABI) or neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer’s Disease and Multiple Sclerosis). Prevalence data indicate that at least 5% of people in Australia [Citation2] and the USA [Citation3] have some form of cognitive impairment due to intellectual disability or ABI and thus may require significant levels of support for decision-making.

The right of all people with disabilities to participate in decision-making is clearly articulated in the 2006 United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Citation4]. Article 12 of the convention not only articulates the right of persons with disabilities to enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life, but also holds signatory nations responsible for developing appropriate measures to provide access to persons with disabilities with the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity.

In 2014, the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) reported on their examination of laws within the Commonwealth jurisdiction that deny or reduce the equal recognition of people with disability as persons before the law and their ability to exercise legal capacity. The commission proposed a set of National Decision-Making Principles and accompanying Guidelines acknowledging that access to support for decision-making was essential [Citation5]. These principles declare that will, preferences, and rights must direct decisions that affect the lives of people with disabilities making particular reference to support in Principle 2: Persons who require support in decision-making must be provided with access to the support necessary for them to make, communicate, and participate in decisions that affect their lives; and Principle 3: The will, preferences, and rights of persons who may require decision-making support must direct decisions that affect their lives.

While formal acknowledgement of support for people with cognitive disabilities to participate in decision-making is important from a legal standpoint, it is equally important to gather rigorous evidence of what works in terms of ensuring that the will and preferences of people with cognitive disabilities are actually at the center of their decision-making [Citation6]. Early adopters of legal mechanisms to recognize supported decision making such as Representation Agreements in Canada [Citation7] and the Godman system in Sweden [Citation8] have provided little evidence on the operation and outcomes of these mechanisms and consequently contributed little to our understanding of the practice of support in these contexts. Indeed, serious doubts have been raised about the capacity of such schemes to deliver their intended benefits across the full range of people with cognitive disabilities [Citation9–15].

Given increasing formal and legal acknowledgement of the crucial role played by support in the context of decision-making for people with cognitive disabilities, growing attention has been paid to the practice associated with the delivery of support. In Australia, a number of small pilot projects have been developed to deliver support for decision making training to supporters. Using scoping review methodology [Citation16], Bigby, Douglas, Carney, Then, Wiesel, and Smith [Citation17] identified and critically reviewed six pilot projects that were completed between 2010 and 2015 in Australian states and territories. These pilot programs were all small-scale projects with the common aim of supporting participation of people with cognitive disabilities in decision-making about their lives. Each of the projects trialed a model of support centered on a decision maker-supporter dyad. The number of dyads involved in the projects ranged from 6 to 36. The majority of decision makers were adults with mild intellectual disabilities; most of the supporters were unpaid and had some form of preexisting relationship with the person with cognitive disability.

The pilot projects revealed important insights into models for delivering support for decision-making and demonstrated some positive outcomes. However, overall findings provided little evidence about the practice of support or the essential ingredients and effectiveness of training due to the lack of depth and rigor applied within the respective evaluation processes. These limitations are far from specific to these particular programs and reflect a more general problem in disability research, whereby the development of training packages tends to have been based primarily on expert opinion and practice wisdom rather than rigorously developed empirical evidence.

In this paper, our aim is twofold: first, to outline the methodological process of the research program that has underpinned the development of a framework to guide the practice of decision-making supporters; and second, to describe the resultant framework and its application. We developed this practice framework as a support for decision-making framework so that it could be applied flexibly within current informal (e.g., support from families or service providers) and formal (e.g., guardianship or substitute decision making), and developing formal (e.g., supported decision making) legal frameworks in Australia and elsewhere by supporters of people with cognitive disabilities. Thus, the practice framework was designed to accommodate the variable and specific provisions of local legislation. For example, it can be used to guide the practice of support for decision making within the specific legislative guidelines around decision-making in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) in England and Wales [Citation18], the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 (ADMA) in Ireland [Citation19] and the variable and changing state-based legislative contexts across Australia. It was conceptualized as being applicable to people with intellectual disability or ABI. Both of these groups have broadly stable rather than declining levels of cognitive impairment characterized by executive function, self-direction, and communication difficulties of varying severity ranging from mild to severe and profound. It is also important to note that a person’s need for decision-making support is not static and may fluctuate as a function of the nature of the decision to be made, the requirements of the legislative jurisdiction, the current situation, and related circumstances for the person. Indeed for some people, support may only be required for specific decisions. This framework can be used flexibly to support decision making across the continuum of self-generated, through shared to substitute decisions.

Each of the authors had a longstanding interest in decision-making issues for these particular groups of adults, people with ABI and people with intellectual disability respectively, which had grown out of both academic research and professional practice. For example, the second author had explored parental planning for the future, and identified the effectiveness of “key person succession plans” in the transition from parental care for middle-aged adults with intellectual disability and the continuing role of siblings in decision-making support in later life [Citation20]. Subsequent research on the lived experiences of older people with intellectual disability, who had spent much of their lives in supported accommodation services had demonstrated however, that others made decisions about their lives, service providers did not listen and take notice of what older people said, and “policies of individualised services and planning that reflect the individual’s needs and goals had not touched their lives” [Citation21,p(0).228]. For adults with ABI, the first author had explored the experience of choice making in the context of leisure activity [Citation22], the conceptualization of self and its impact on personal goal setting, choice making for people with ABI during rehabilitation [Citation23], and while living long term in the community [Citation24].

With this early research as background, the authors chose a four-phase approach modeled on the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions [Citation25,Citation26] to direct the research process underpinning the development of a support for decision-making practice framework. To date the resultant findings have been published progressively to inform current practice and update progress. Our decision to use MRC guidance reflected the complex nature of the construct of support for decision making and in turn the likely complexity of a practice framework (intervention) designed to improve the delivery and outcomes of decision-making support.

Complex interventions typically include interacting and overlapping components, require a number of behaviors by those delivering the intervention, target a number of groups or organizational levels and require a degree of flexibility or tailoring in their delivery [Citation26]. All these characteristics apply to training/intervention in the domain of support for decision making with people with cognitive disabilities. Support for decision making is clearly a complex process with multiple players (e.g., the person with cognitive disability, the supporter, others influencing or impacted by the decision) across a range of components (e.g., identifying the decision; implementing the decision) that requires ongoing tailoring across multiple factors (e.g., the personal attributes of the individual with cognitive disability including his or her life stage, the characteristics of the physical, social, and organizational environment). In this paper we focus principally on describing phases one and two (development, feasibility and piloting) of the overall development and evaluation process. We then outline the evaluation of effectiveness (phase three) that is currently underway and implementation (phase four) activities that are planned.

Method

Research program

The overall development and evaluation program for the La Trobe framework for the Delivery of Support for Decision Making [Citation27] encompasses the four broad phases outlined by Craig et al. [Citation26]: development, feasibility and piloting, evaluation, and implementation (see ). All projects undertaken to inform the development and evaluation of the practice framework were commenced following receipt of approval from the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee.

Figure 1. Process of development and evaluation: modeled after Craig et al. [Citation24].

![Figure 1. Process of development and evaluation: modeled after Craig et al. [Citation24].](/cms/asset/0cd1d6d7-b894-486d-a273-69b906f83039/idre_a_1498546_f0001_b.jpg)

Phase one: development

During the development phase our aim was to locate and use the best available evidence relating to provision of support for decision making to people with cognitive disabilities. We addressed this aim by (1) systematically searching and reviewing the peer-reviewed literature; and (2) undertaking qualitative exploration of the experience of support for decision making from the perspective of people with cognitive disabilities and their supporters.

Reviewing the literature

The systematic review covered the peer-reviewed literature from 2000 and was completed in September 2014. The search strategy, yield and review results are detailed in the report produced for the project funders [Citation28]. The search was guided by the broad research question; what is the research evidence about the processes of providing support for decision making of people with intellectual disability or ABI? The combined searches of four databases produced 1642 references (excluding duplicates). Papers were excluded if: they were commentaries rather than reporting research; did not specifically address the processes of support for decision making of people with either intellectual disability or ABI; involved children rather than adults; focused only on measurements for assessing capacity; reported experimental assessments of choice making in artificial as opposed to real life settings; and only described the absence of choice or decision making rather than processes of support. A total of 54 papers including three in press articles comprised the final yield.

Most of the studies (46/54) were concerned with adults with intellectual disabilities and only eight involved participants with ABI [Citation29–36]. Our own recently published articles [Citation33–35] were the only studies that focused on people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and their supporters (spouses/partners, parents, friends, and paid workers). The presence of spousal supporters in this group revealed a notable contrast with studies of people with intellectual disability where spousal supporters are largely absent and family supporters are typically parents or in the case of older people, siblings.

Overall the final yield represented a relatively small body of literature reflecting a weak evidence base, with few large scale or methodologically rigorous studies. Very few of the studies focused specifically on processes of support for decision making and instead choice or decision making was included as one of several factors investigated. For example, Ellem, O'Connor, Wilson, and Williams [Citation37] included support for decision making as part of their study of social work practice with marginalized groups. The types of choice or decisions considered varied widely across studies, although issues of sexuality and health had received more attention than other decision areas. Constraints associated with risk management, assumptions about best interests, and the impact of limited time frames on decisions were evident. For example, Burgen [Citation31] highlighted how timeliness of support may actually reduce the options considered in making a decision about pregnancy.

A diverse range of situational contexts was sampled across the studies. The most frequently encountered contexts included decision making in the context of service provision by staff in supported accommodation or vocational settings, group situations such as self-advocacy, planning, transition or interdisciplinary meetings, health settings targeting support by nurses, other medical professionals, and family contexts. In general, decision types were most commonly broken up by magnitude and life space of the decision such as “big” major life space (e.g., who you live with, what kind of job you have, how to manage finances) or “small” everyday life space (e.g., what you have for breakfast, what you wear).

Across the body of research a number of supporter characteristics and skills were identified as enabling people with cognitive disability to participate in decision making. Examples of enabling characteristics included supporters having a positive attitude towards people with cognitive disability exercising choice, control, and creating decision making opportunities [Citation30,Citation33,Citation38–43]; being self-aware; able to suspend one’s own judgments and able to adopt a neutral and non-judgmental stance in providing support for decision making [Citation37]; having a positive relationship with the individual based on trust and understanding [Citation31,Citation33–35]; knowing about a person’s cognitive impairment and being able to adjust support and communication to the strengths and weaknesses of the individual [Citation33,Citation44–46].

Exploring the experience of people with cognitive disabilities and their supporters

In order to understand and characterize the experience of support for decision making, researchers from the Living with Disability Research Centre at La Trobe University conducted seven exploratory studies with people with intellectual disability, people with ABI, and those who support them to participate in decision-making. This work has been conducted in a constructivist framework [Citation47] employing interview (individual and focus group) and observational methods to generate data then analyzed using Grounded Theory principles and procedures. This body of research has given rise to 13 published articles [Citation9,Citation13,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28,Citation33–35,Citation48–52] that together build a rich understanding of support for decision making in the lives of people with cognitive disabilities. Overall this work has benefitted from in-depth exploration of the experiences of 52 adults with cognitive disabilities and 75 supporters. These qualitative studies have revealed a diverse range of factors that impact on the process of providing support and the strategies used. Taken together the findings demonstrated that:

…people with cognitive disabilities have a “positive” or “successful” experience of decision-making support, if support is provided by one or more individuals with whom they have a trusting relationship; who have a knowledge of their history and goals (including previous decisions and outcomes), and the nature of their impairment and level of functioning; who are flexible and use variable strategies to tailor their support to the unique needs and characteristics of each individual; and who collaborate with the individual to reach their desired outcome. [Citation13, p. 40].

The findings also demonstrated the uncertainty about roles of family members in decision support, the potential for them to be excluded from decision processes, and for reversion by health or disability service providers to traditional professional paradigms [Citation48]. They identified the need for clearer processes of decision making support to ensure the perspective of people with cognitive disabilities are taken into account and the absence of mediation processes to resolve competing perspectives of formal and informal supporters. Overall, analysis of the body of data from people with cognitive disabilities and their supporters showed that support for decision-making was a multi-component process that did not proceed in a fixed order, could be fulfilled in a recursive manner, and benefitted from the influence of a set of overarching principles. Together with the insights afforded by the systematic review, the “lived” experience evidence gave rise to the La Trobe Support for Decision Making Practice Framework [Citation27].

Phase two: feasibility and piloting

The Framework was piloted with the support of funding from New South Wales, Family and Community Services (phase two of development and evaluation, ). Training procedures and strategies were tested with support workers and health professionals working with 45 people with cognitive disability in a large residential setting. Following this pilot phase, revisions were made, and a training manual developed.

Phase three: evaluation

Following development of customized measures, the framework is currently being evaluated through a randomized control trial (phase three, ) funded by an Australian Research Council – Linkage grant [Citation53]. Two parallel impairment-specific randomized controlled trials (supporters of people with ID and supporters of people with ABI) are underway using blinded randomized assignment to the education program and waitlist control conditions within each of the impairment groups. The effectiveness of the training (intervention) program will be evaluated for each impairment group contrasting the waitlist and intervention groups on pre-intervention, post-intervention, 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up measures. This project uses a mixed method design with both quantitative and qualitative measures. Process-related outcomes are being evaluated through interviews at each time point, data from which will be used to build an understanding of the change process.

Results

The La Trobe support for decision-making practice framework

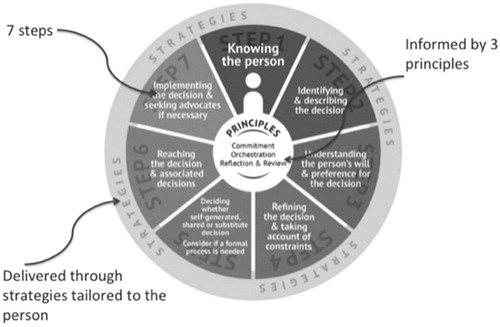

Based on our research findings to date, the support for decision-making process is conceptualized as comprising seven components or steps, delivered through individually tailored strategies, and informed by three principles. is a schematic representation of the process. However, it is emphasized that the real world is less ordered and although the steps are depicted as separate elements in the figure, they are considered part of an iterative process, can often occur simultaneously, and re-occur in the context of a single decision process.

The framework was built progressively based on analysis of the data, the results documented across the systematic review, and each of the completed qualitative studies. illustrates this process demonstrating the contribution the findings of completed studies have made to the evolution of the framework.

Table 1. Findings contributing to the La Trobe Support for Decision Making Practice Framework.

Support for decision-making steps

Step 1: Knowing the person. Support for decision-making is a person centered process and supporters need to “know” the person well. Knowing the person means knowing all aspects of the person and having a sense of the person’s self-identity or self-concept (Who I am and how I feel about myself) [Citation24]. This step usually encompasses knowing about the person’s attributes and style, personal characteristics, likes, dislikes, preferences, skills, the effect of their specific cognitive impairments, their social connections, history, and personal story. Part of knowing a person also means understanding the way they are seen by others in their network including, family, friends, support workers, and the various professional “experts” who have been involved in their life. Knowledge of what defines the person provides the conceptual context for understanding their will and preferences.

Step 2: Identifying and describing the decision. In order to provide effective support, it is necessary to describe the decision and its features in full: its scope (how much it is likely to impact on a person’s life and the other decisions that might flow from it); who should be involved in helping the person to make the decision or the formal organizations that may be involved (such as the criminal justice system or health system); the constraining factors that will help shape the decision, or may be taken for granted and that may need to be challenged by supporters; the time frame available in which to make the decision, and the potential consequences of choosing one decision option over others. Describing a decision helps to focus attention on the core issues, guide who to involve, identify tensions that might arise and constraining factors that might be amenable to change and clarify the potential flow on effects of this decision to other parts of a person’s life.

Step 3: Understanding a person’s will and preferences about the decision. This component is a “blue sky” step in the process. The person and their supporters think as widely as possible about the decision, all the possible options that need to be explored, the person’s preferences about all the things that will be encompassed in the decision, and the consequences of different options. Everyone has preferences. They stem from experiences, knowledge, and available information, personal values or cultural norms. They are communicated in many ways – through words, signs, gestures, expressions, behavior, actions or lack thereof. For some people preferences have to be interpreted by supporters based on their knowledge of the person, or garnered from the perspectives of others who know the person well or in different contexts.

Step 4: Refining the decision and taking account of constraints. A decision is more than a dream or hopeful statement in a plan; it must be implementable. In this fourth step preferences are prioritized, refined and shaped by constraints such as time, money, impact on other people, and safety. Ways are found to ensure the decision will be implemented, and potential constraints might be questioned or creatively managed.

Step 5: Considering whether a self-generated, shared or substitute decision is to be made. This step distills the knowledge gained in earlier steps about the decision, preferences, priorities, constraints and consequences. The manner in which the decision is to be reached is based on the knowledge accumulated about the specific decision and the person’s own skills. Indeed it may well become clear that the person can self-generate the decision with little or no support throughout the process. In other situations, anticipated harm to self or others or unresolved conflict about reaching a shared decision, may indicate that support for a more formal process of making a substitute decision may be appropriate by for example, application for a guardian. In the situation where a person already has a guardian in place, then the decision making supporter provides the guardian with all the relevant information to support a decision that reflects the person’s will, and preferences.

Step 6: Reaching the decision and associated decisions. At this step, the decision is made to reflect prioritized preferences as closely as possible. The many consequential decisions that will flow from a major decision will become clearer. In supporting each of these smaller decisions the support for decision making cycle loops back through the process and is repeated. At this step depending on the decision, it may be formally recorded and communicated to others involved in the person’s life, formal or informal, who will support its implementation.

Step 7: Implementing a decision and seeking out advocates if necessary. Decision-making can often falter because the tasks, the power, or resources necessary to implement the decision may be beyond the scope of the supporters involved in earlier stages of the decision-making process. Implementation may not rest with decision-making supporters and supporters may seek out advocates to support implementation of the decision or others in a person’s circle may shift into an advocacy role to make sure the decision is followed through by actions. The processes of support do not stop here; as the person being supported is likely to be involved in making consequential decisions and other unrelated decisions for which support might be needed. Having an advocate or a case manager to help implement a decision will not remove the need for continuing support with decision making.

Principles of support for decision-making

As illustrated in , three principles that inform the support for decision-making process have been identified. These principles are: (1) commitment, (2) orchestration and (3) reflection and review.

Commitment means that first and foremost, supporters must have a relationship with the person and a commitment to upholding their rights. The relationship does not have to be “excellent” or “perfect” but it does have to be underpinned by unconditional regard for the person as a human being of equal value and a holder of rights. With equality and rights as foundational beliefs, supporters are more likely to have positive expectations about the person’s participation in decision making, and to respect their opinions and preferences rather than subordinating them to those of others in the decision making space (e.g., family members, staff, experts).

Orchestration relates to the shared nature of support for decision making which involves a range of people who know the person in different ways, such as a friend, a family member, and perhaps more instrumentally as a client who requires intensive and costly support with everyday activities. Supporters may include immediate or extended family, direct support workers, managerial staff, and subject matter experts. A primary supporter leads and orchestrates support, drawing in other supporters, both formal and informal from various parts of the person’s life, as well as mediating any differences. If such a lead person is not evident then, for some decisions, it will be necessary to find someone willing to take on that role.

Reflection and review captures the self-awareness and continuous reflection supporters need to maintain in order to hold a neutral non-judgmental stance that puts aside their own preferences. Continuous reflection by supporters on their own values, their own stake in the decision and potential to influence the person being supported will help ensure the decision making agenda remains based on the will, preferences, and rights of the person they are supporting. Supporters need to employ a self-questioning strategy, applying self-checks and balances to each decision situation, and remain vigilant to points where they are particularly vulnerable to providing biased, value-laden or constrained support. Effective support for decision making is transparent and accountable meaning that supporters should be open to review by others, able to articulate their reasoning processes, describe the observations, experience and knowledge they have used to inform their support, and track this through to the point of decision.

Strategies for practice

Strategies are needed for each step of the support for decision-making process and for putting support principles into practice. Strategies can be seen as providing access to information and or opportunities to widen experiences of what might be possible; enabling, ascertaining or interpreting a person’s preferences, and helping to understand constraints and consequences. Supporters need a wide repertoire of nuanced strategies that can be tailored to the person and the decision at hand. Effective strategies are person centered and will depend on timing and situational factors, the significance, scope and nature of the decision, and who else might be involved in or affected by the decision (see for a range of strategies identified in our research findings and Douglas [Citation24] for additional strategies to support interactions with people with cognitive difficulties).

Table 2. Practice strategies identified through research.

Delivery of the support for decision making training

This practice framework has been designed with a view to flexible delivery of training. To date, it has been piloted successfully in face-to-face training sessions in small and large group environments with a range of participants including, family members, support workers, public guardians, allied health professionals, and community case workers. It is well suited to further development and evaluation as a structured online learning package along with a suite of audio-visual training resources that we have developed.

Discussion

From the perspective of self-determination, it is clear that good support for decision-making is crucial. It enables the will and preferences of people with cognitive disabilities to be central to their decisions and increases their control over their own lives. In turn, this can positively affect the self-identity, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life of people with cognitive disabilities. Developments such as those reflected in the principles outlined in the reports of the ALRC [Citation5] and the LCO [Citation15], in amendments to legislation such as the Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act (2008) in Alberta, Canada [Citation54] and the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act (2015) in Ireland [Citation19] and in the recently introduced National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS, 2013) in Australia [Citation55] demonstrate the pressing need for an evidence-based and effective practice framework with associated training materials that have applicability across the diverse informal and formal contexts in which support for decision-making occurs.

Until now, limited empirical investigation into the practice of support for decision making has meant that our current tools to guide support have been largely based on ideology, principles drawn from social, health, and legal professional practices, or practice wisdom rather than empirical evidence. However, it is essential that training programs are evidence-based and rigorously evaluated in terms of impact and potential to shape the attitudes and skill of decision-making supporters, and in turn the sense of control of those in receipt of support.

The framework that we have described in this article has been systematically developed and is undergoing evaluation through a four–phase research program. The framework is the first to provide an evidence-based guide for engaging in effective support for decision-making. It has been subjected to pilot evaluation and feasibility testing. Further evaluation of the implementation and the short- and long-term effectiveness of this framework is currently underway through an ARC-Linkage project [Citation53] comprising two parallel, randomized controlled trials drawing on participants with intellectual disability and ABI, and their supporters across eastern Australia. This trial will not only deliver evidence of the effectiveness of the framework but also provide insights into the characteristics of the change process underpinned by participation in the training.

Although this framework has been rigorously developed to target support for decision making with two groups of people with cognitive disabilities, intellectual disability and ABI, the support process described is conceptually applicable more broadly to other groups. Thus, additional evaluation of the framework with people with degenerative disorders giving rise to dementia/declining cognitive ability and people with mental health problems giving rise to intermittent periods of compromised cognitive ability and those who support them is recommended. Finally we see this framework as a vehicle for change whereby people with cognitive disabilities who have been delegated as passengers in their own lives are effectively supported to drive their own futures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Disabled World [internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.disabled-world.com/disability/statistics

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Canberra (ACT): Australia’s welfare; 2013. (AIHW).

- US Census Bureau. Washington (DC): American Community Survey (ACS); 2014.

- United Nations (UN). Geneva. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; 2006.

- Australian Law Reform Commission. Sydney (NSW): Equality, capacity and disability in Commonwealth laws (DP 81); 2014.

- Mason A. Foreword. Univ N S W Law J. 2013;36:170–174.

- Gordon R. The emergence of assisted (supported) decision-making in the Canadian law of adult guardianship and substitute decision-making. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2000;23:61–77.

- Gooding PM. Supported decision-making: a rights-based disability concept and its implications for mental health law. Psychiatr Psychol Law. 2013;20:431–451. 2012;

- Bigby C, Whiteside M, Douglas J. Providing support for decision making to adults with intellectual disability: perspectives of family members and workers in disability support services. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;1–14.

- Carney T. Participation and service access rights for people with intellectual disability: a role for law. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;38:59–69.

- Carney T. Clarifying, operationalising and evaluating supported decision making models. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2014;1:46–50.

- Carney T, Beaupert F. Public and private bricolage-challenges balancing law, services and civil society in advancing CRPD supported decision making. Univ N S W Law J. 2013;36:175–201.

- Douglas J, Bigby C, Knox L, et al. Factors that underpin the delivery of effective decision-making support for people with cognitive disability. RAPIDD. 2015;2:37–44.

- Kohn NA, Blumenthal JA. A critical assessment of supported decision-making for persons aging with intellectual disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2014;7:S40–S43.

- Law Commission Ontario (LCO) Toronto (Ontario): Legal capacity, decision-making and guardianship. Discussion Paper May 2014. 2014.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Carney T, et al. Delivering decision-making support to people with cognitive disability–what has been learned from pilot programs in Australia from 2010–2015. Aust J Soc Issues. 2017;52:222–240.

- Mental Capacity Act. Code of Practice. (2005). [cited 2018 May 28]. Available from: http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/pls/portallive/docs/1/51771696.PDF.

- Government of Ireland. Dublin (IE) Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act. 2015.

- Bigby C. Moving on without parents: Planning, transitions and sources of support for older adults with intellectual disabilities. New South Wales/Baltimore: Mclennan + Petty/P H Brookes; 2000.

- Bigby C, Knox M. ‘I want to see the Queen’, the service experiences of older adults with intellectual disability. Australian Social Work. 2009;62:216–231.

- Douglas J, Dyson M, Foreman P. Increasing leisure activity following severe traumatic brain injury: does it make a difference? Brain. Impair. 2006;7:107–118.

- Douglas J. Placing brain injury rehabilitation in the context of the self and meaningful engagement. Semin Speech Lang. 2010;31:197–204.

- Douglas J. Conceptualizing self and maintaining social connection following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2013;27:60–74.

- ] Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–696.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;33:a1655.

- Bigby C, Douglas J. Sydney, NSW. Support for Decision Making: a Practice Framework; 2016. Living with Disability Research Centre, La Trobe University http://hdl.handle.net/1959.9/556875

- Bigby C, Whiteside M, Douglas J. Supporting people with cognitive disabilities in decision making: processes and dilemmas. Melbourne (VIC): Living with Disability Research Center, La Trobe University; 2015.

- Abreu B, Zhang L, Seale G, et al. Interdisciplinary meetings: investigating the collaboration between persons with brain injury and treatment teams. Brain Injury. 2002;16:691–704.

- Agran M, Storey K, Krupp M. Choosing and choice making are not the same: asking “what do you want for lunch?” is not self-determination. J Vocat Rehabil. 2010;33:77–88.

- Burgen B. Women with cognitive impairment and unplanned or unwanted pregnancy: a 2-year audit of women contacting the pregnancy advisory service. Australian Social Work. 2010;63:18–34.

- Hill S, Wooldridge J. Informed participation in TennCare by people with disabilities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17:851–875.

- Knox L, Douglas J, Bigby C. ‘The biggest thing is trying to live for two people’: spousal experiences of supporting decision-making participation for partners with TBI. Brain Injury. 2015;29:745–757.

- Knox L, Douglas J, Bigby C. Becoming a decision-making supporter for someone with acquired cognitive disability following TBI. RAPIDD 2016;3:12–21.

- Knox L, Douglas J, Bigby C. “I won't be around forever”: understanding the decision-making experiences of adults with severe TBI and their parents. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2016;26:236–260.

- Tasky K, Rudrud E, Schulze K, et al. Using choice to increase on-task behavior in individuals with traumatic brain injury. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41:261–265.

- Ellem K, O'Connor M, Wilson J, et al. Social work with marginalised people who have a mild or borderline intellectual disability: practicing gentleness and encouraging hope. Australian Social Work. 2013;66:56–71.

- Caldwell J. Leadership development of individuals with developmental disabilities in the self‐advocacy movement. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:1004–1014.

- Garcia-Iriarte E, Kramer JC, Kramer JM, et al. ‘Who Did What?’ A participatory action research project to increase group capacity for advocacy. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2009;22:10–22.

- Kjellberg A. More or less independent. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:828–840.

- Mill A, Mayes R, McConnell D. Negotiating autonomy within the family: the experiences of young adults with intellectual disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. 2010;38:194–200.

- Renblad K. How do people with intellectual disabilities think about empowerment and information and communication technology (ICT)? Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26:175–182.

- Timmons J, Hall A, Bose J, et al. Choosing employment: factors that impact employment decisions for individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49:285–299.

- Antaki C, Finlay W, Walton C, et al. Offering choices to people with intellectual disabilities: an interactional study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52:1165–1175.

- Rossow-Kimball B, Goodwin D. Self-determination and leisure experiences of women living in two group homes. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2009;26:1–20.

- Schelly D. Problems associated with choice and quality of life for an individual with intellectual disability: a personal assistant's reflexive ethnography. Disabil Soc. 2008;23:719–732.

- Charmaz K. Constructionism and the grounded theory method. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF, editors. Handbook of constructionist research. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2007. p. 397–412.

- Bigby C, Bowers B, Webber R. Planning and decision making about the future care of older group home residents and transition to residential aged care. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55:777–789.

- Bigby C, Webber R, Bowers B. Sibling roles in the lives of older group home residents with intellectual disability: working with staff to safeguard wellbeing. Australian Social Work. 2015;68:453–468.

- Douglas J, Drummond M, Knox L, et al. Re-thinking social relational perspectives in rehabilitation: traumatic brain injury as a case study. In: McPherson K, Gibson BE, Leplege A, editors. Rethinking rehabilitation: theory and practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015. p. 137–162.

- Knox L, Douglas J, Bigby C. Whose decision is it anyway? How clinicians support decision-making participation after acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1926–1932.

- Knox L, Douglas J, Bigby C. “I’ve never been a yes person”: decision-making participation and self-conceptualisation after severe traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:2250–2260.

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Carney T, et al. Effective Decision Making Support for People with Cognitive Disability 2015; Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP150100391).

- Alberta Government. Edmonton (Alberta). Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act. 2008.

- Australian Government. Canberra (ACT). National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. 2013