Abstract

Purpose: To explore barriers and pathways to the inclusion of persons with mental and intellectual disabilities in technical and vocational education and training programmes in four East African countries, in order to pave the way to greater inclusion.

Materials and methods: An explorative, qualitative study including 10 in-depth interviews and a group discussion was conducted with coordinators of different programmes in four East African countries. Two independent researchers coded the interviews inductively using Atlas.ti. The underlying framework used is the culture, structure, and practice model.

Results: Barriers and pathways to inclusion were found in the three interrelated components of the model. They are mutually reinforcing and are thus not independent of one another. Barriers regarding culture include negative attitudes towards persons with mental illnesses, structural barriers relate to exclusion from primary school, rigid curricula and untrained teachers and unclear policies. Culture and structure hence severely hinder a practice of including persons with mental disabilities in technical and vocational education and training programmes. Pathways suggested are aiming for a clearer policy, more flexible curricula, improved teacher training and more inclusive attitudes.

Conclusions: In order to overcome the identified complex barriers, systemic changes are necessary. Suggested pathways for programme coordinators serve as a starting point.

Clear and up-to-date information on mental disability is required to engender societal participation; especially that of stakeholders in technical and vocational education and training programmes.

Affirmative action and policy implementations of national and international human rights legislations are required to address the challenges of enrolment in technical and vocational education and training programmes.

Disability organisations and government should adopt a more open and strengths-based attitude, tailor-made curricula, specific teacher training as well as clearer policies to ensure better inclusion of persons with mental disabilities in technical and vocational education and training programmes.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Persons with disabilities face serious employment challenges, particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). As a response, a great number of projects and programmes have been introduced aiming to enhance the chances of employment for persons with disabilities. Supported employment, sheltered employment, and inclusive redesign of work processes, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) are used worldwide to enhance employment opportunities for persons with a disability [Citation1–3]. TVET as a pathway to employment is supported by most national legislation as well as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) [Citation2,Citation4,Citation5]. Evidence of the value of TVET abound [Citation6,Citation7]. For instance, in their systematic review of TVET in LMICs, Tripney and Hombrados [Citation7] report a positive association between TVET and employment outcomes. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) recommend the acquisition of vocational skills as a means to facilitate formal and informal employment for persons with disabilities [Citation8]. In addition, inclusive education is relevant to achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) 4 and 8 for education and work, respectively [Citation2,Citation9].

Despite being designed to focus on persons with all kinds of disabilities, it was found that only a small number of programmes include persons with mental disabilities [Citation2,Citation4,Citation10,Citation11]. Mental illness, however, has been found to affect concentration, working memory, social interactions, and working capacity, all of which constitute considerable employment hurdles [Citation12–14]. Furthermore, stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness affect the employment opportunities of persons with such an illness [Citation1,Citation2,Citation7,Citation15,Citation16]. It is assumed that persons with mental disabilities would greatly benefit from participating in the programmes.

While the precise reasons and mechanisms of exclusion of persons with mental illness are yet to be understood, the very definition of mental disability might be one of the key factors. Severe mental illness is considered a disability in the international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) [Citation17]. Despite this categorisation, it has been found that persons with mental illness and their communities often do not consider themselves as persons with disabilities [Citation18–20]. In a study of persons with mental illness, Thoits [Citation20] characterised this attitude as a form of identity deflection in order to resist stigma. This discrepancy may be a factor that explains why programmes to enhance the inclusion of persons with mental disability have often not succeeded as well as initiatives focusing on other disabilities.

There are also known and large cross-cultural differences in the understanding and perception of mental illness: “culture is fundamental both to the course and the cause of psychopathology” [Citation21]. The ICF is based on the biopsychosocial understanding of mental illness, which defines it as a disability; however, there are significant differences in explanations of mental illness in sub-Saharan African countries [Citation22]. Hence, persons with mental illness are often originally targeted in the design of the programmes, as for example by Light for the World, which considers inclusive development to encompass all people with disabilities, including those with mental illness. However, individuals with mental disability might still not benefit from the programmes as neither they themselves nor their immediate environment perceives them as persons with disabilities. For this study mental disability refers to either common or severe mental disorders that impair an individual’s social and occupational functioning [Citation17,Citation23].

The aim of this study is to unravel the reasons and mechanisms behind the limited inclusion as well as to identify pathways towards enhanced inclusion of persons with mental disabilities in TVET programmes in East Africa. The findings are expected to inform policy makers and non-government organisations (NGOs), and enhance the employment opportunities of individuals with mental disabilities in the long run.

Theoretical framework

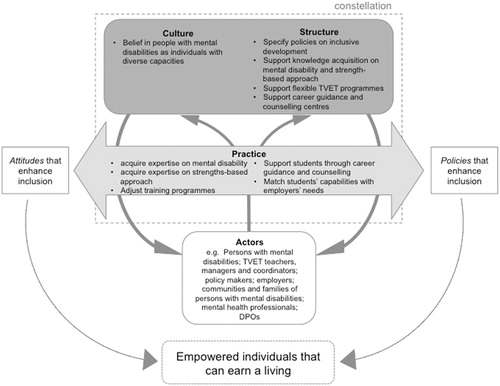

A theoretical model was used in order to systematically analyse the data. The structure, culture, and practice model is applied here [Citation24], and has been widely used in system theory to understand the functioning of societal systems such as health systems [Citation25]. This interaction between culture, structure, and practice is conceived as a possible enabler or constraint to functioning in social and health systems [Citation25]. Structure, culture, and practice together form constellations that “both define and fulfil a function in a larger societal system” [Citation24]. The practices of actors (what is being done) are shaped by both the culture (the shared way of thinking) and the structure (the way things are regulated). At the same time the practices, through the agency of the actors, influence both the culture and the structure. Thus, between the three, there are recursive interactions (see ).

Figure 1. Framework based on van Raak [Citation24].

![Figure 1. Framework based on van Raak [Citation24].](/cms/asset/486b6508-a429-4d0b-af6c-5c0326104025/idre_a_1503729_f0001_b.jpg)

More concretely and adapted to the context of this study, practices include the way people act towards persons with a mental or intellectual disability and their inclusion in (or exclusion from) TVET programmes. The culture includes all thoughts, norms, values that actors in the context attribute to persons with mental disability. Beliefs and practices relating to mental illness can lead to discrimination and hinder access to development programmes [Citation26]. Finally, the structure entails the laws and policies regarding people with mental disability, e.g., the admission requirements to TVET programmes or the training of teachers.

These three concepts are not independent of one another, but, as depicted by the arrows in , dynamically influence one another. Actors’ thoughts about people with mental disabilities are shaped by and shape the policies and laws in place [Citation27], and at the same time define the practices of actors [Citation26,Citation28]. The interactions with persons with mental disabilities, i.e., the practices, also shape both the beliefs (i.e., the culture) and the regulations (i.e., the admission criteria and policies defining who benefits and who does not). Barriers and pathways to the inclusion of persons with mental disabilities in the TVET programmes are hence analysed along the three main concepts and their intersections.

Introduction of the case

UNESCO defines TVET as “those aspects of the educational process involving, in addition to general education, the study of technologies and related sciences and the acquisition of practical skills, attitudes, understanding, and knowledge relating to occupation in various sectors of economic life” [Citation29]. TVET is designed to achieve the right to education and inclusiveness for all persons, including persons with disabilities [Citation29]. TVET programmes are either public or private and are organised by local governments, faith-based organisations, or NGOs. Disability-specific NGOs like Light for the World Netherlands in collaboration with local disabled persons organisations (DPOs) support TVET programmes so as to improve access to education and employment for persons with disabilities. Light for the World Netherlands started the EmployAble programme through which it works with TVET organisations in East Africa. In Kenya, TVET training is offered through vocational institutions like Technobrain, Baraka Agricultural College and Kabete Technical Training Institute [Citation30]. A recent report of Light for the World, revealed that of 406 youths with disabilities enrolled in TVET only 7% were found to be persons with mental/psychosocial disabilities [Citation30].

Methods

Design

A qualitative, exploratory study was conducted with TVET organisations in four East African countries – Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. The organisations in the countries were chosen because of their collaboration with Light for the World Netherlands. The main method used was semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted via Skype and face-to-face interviews in Kenya. Purposive sampling was used to include participants who are TVET and DPO coordinators in managerial positions and who were involved in the initial phase of the EmployAble programme in the selected countries. They are assumed to be especially knowledgeable about the TVET recruitment process and with years of work experience in the disability sector in their countries. All 10 TVET and DPO coordinators contacted (six men and four women) agreed to participate in the study. They were five DPO coordinators and five TVET coordinators in Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. When no new themes or ideas emerged in the interviews and discussions with the study participants, data saturation was reached and no further participants were invited to participate in the study. A group discussion with participating TVET and DPO coordinators in Kenya was held in order to validate findings. In addition, coordinators of mental health organisations were invited and they provided insights on their conceptualisation of the difference between intellectual and mental disabilities.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection took place between November 2016 and May 2017 as part of a formative research process [Citation31]. In the interviews, factors relating to the inclusion or exclusion of persons with mental illnesses in TVET programmes were explored. The role and attitude of teachers, employers, families, and communities as well as policies and regulations were investigated. Data collection followed an iterative process, with emerging issues from earlier interviews used to modify themes probed in subsequent interviews.

IDE conducted eight interviews via Skype and two face-to-face follow-up interviews. The discussions were conducted in English and lasted between 45 and 90 min. The audio records were transcribed verbatim. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Observations and field notes made during visits to TVET sites and meetings with TVET providers were also incorporated in the analysis.

The transcripts and field notes were imported into Atlas.ti software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) [Citation32] and two independent researchers, IDE, and ESR, inductively coded the interviews. After the initial round of coding, over 12 codes generated by the different researchers were compared and differences resolved in discussion with the JFGB and BJR. Five common themes emerged, which informed the final analysis.

Ethics

The study design was approved by the Amsterdam Public Health science committee (WC2017-011). The Maseno University Ethics Review committee approved the study (MSU/DRPI/MUERC/00391/17).

Results

Barriers and pathways to the practice of inclusion of persons with mental disability were found to relate to the underlying culture and structure, as well as their intersections. Before laying out the barriers and pathways, we discuss what is understood as mental illness and disability.

Understanding mental disability

Beliefs about what mental illness entails and in how far it is considered a disability were explored. While the UNCRPD makes a distinction between persons with mental and intellectual impairments and physical and sensory impairments (UNCRPD, Article 1) [Citation5] and understands both as disabilities, most participants do not consider mental impairments as disabilities and also do not always recognise mental health conditions as distinct from intellectual disability.

Study participants argued that mental illness is not a disability, because it is not necessarily a long-term condition and because of its reversible character, either with medication or with the help of psycho-social support.

Our organisation […] for mental disability actually categorises mental disability into two […]: mental illness and then there is […] madness. Madness […] require[s] medical attention. But people with mental illness do not require so much of medical attention, they may need psychosocial support, they may need family support and those could be actually reinstated. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

So, depending on the severity of the mental disability, it is possible to rehabilitate people. She further differentiates between mental and intellectual disability, saying “for the case of [my country] we actually have an organization working with intellectual disability and one working on mental health. So they are different categories according to us.” (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience).

Another study participant highlighted the treatable character of mental illness, a differentiating feature to intellectual disability.

[…] people with intellectual disability are often […] people with a low intelligence quotient, […] their understanding is impaired. Whereas those with mental illness are people with […] depression, anxiety disorder, autistic disorder […]. If they are on their drugs, they are ok, but if they are not […], that’s when their challenges are more obvious. (DPO Coordinator 1_> 5 years experience)

In spite of this difference, he merges the categories of mental illness and intellectual disability:

Generally, there is a lot of confusion when it comes to children, youths and adults with mental disability. In other words, I term them as people with intellectual impairment. Don’t mind about that. (DPO Coordinator 1_>5 years experience)

Two further study participants add to the complexity by making a distinction between a global and a local definition of mental illness. One states “the global literature is saying [that] a mental health condition is also [a] disability but for our case we don’t consider mental health conditions as […] disabilities.” (DPO Coordinator 3_>5 years experience). Another respondent comments along similar lines, “In [my country], I don’t think mental illness is considered as a disability” (TVET Coordinator 1_<5 years experience).

As this study was conducted in the context of the EmployAble programme, which groups together mental/psychosocial impairments, including learning impairments (as distinct from visual, hearing, and physical impairments), we decided to include barriers and pathways regarding the inclusion of people with intellectual and mental disabilities. Both groups were scarcely included in the programmes so far, and the participants elaborated on the underlying reasons, which were to some extent generic. Where possible and relevant, we explain the type of disabilities to which the participants refer.

As mentioned earlier, only 7% of those enrolled in the TVET programmes in the context of the EmployAble programme were people with mental/psychosocial impairments. In order to understand the underlying mechanisms for this lack of inclusion (practice), we consider barriers that were identified that reflect underlying norms and beliefs (culture) and barriers that pertain to structures. Practices hence, conceptualised as the results as well as cause of both cultures and structures, and are not analysed in a separate section, but within the sections on culture and structure.

Culture

The way mental illness is understood by society is reflected in the norms and beliefs that structure the interactions with individuals with mental disabilities. The following section elaborates on norms and actions taken towards individuals considered to have mental illnesses. First barriers and then pathways are delineated.

Both teachers and employers were reported to be hesitant to include persons with mental impairments. Two main underlying reasons emerged: first, a belief that persons with mental disability are violent, which is prominent particularly in the school context; and second, that they do not learn fast enough or are unproductive, an argument put forward by teachers and employers. The following elaborates on these two sets of internalised beliefs.

One participant explains how mental illness is linked to violence. He asserts that:

[…] the attitude of people, not only the community but also the professionals; […] towards these people; because […] whenever they hear about the mental health conditions they think that these people are kind of aggressive. […] whenever the case of mental health has been the focus […], the discussion goes to the point at which this people could be violent. (DPO Coordinator 3_>5 years experience)

Another participant seems to have adopted this perspective, she states:

But in most cases people with mental disability tend to reach the violent side. They tend to be more talkative, more destructive and some of them actually reach an extent of being sick. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

The second assumption is that person with mental or intellectual disability needs a large amount of support and learn too slowly. One participant states: “Because the thinking in people’s mind is that these people can still not learn and if they learn they need a long time they need more support” (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience). They are also thought of as not needing to go to school or needing to go to a special school as they cannot keep up with their classmates. One participant summarised what, according to him, many would think:

… take him [a person with a mental illness] to somewhere maybe […] to […] some specialised training institute […] like mat making or broom making, brush making. He adds that these training institutes are ''not as such productive for the users to gain […] their livelihood''. (DPO Coordinator 3_>5 years experience)

The study participants suggest that the slow learning of persons with intellectual disability is the official explanation of sending them to special schools and excluding them from regular schools. However, given the fact that persons with mental illness are thought of as being violent, segregating people with and without mental illness might be an outcome that is, if not intended, welcomed by many.

As elaborated upon by several participants, employers also assume that persons with mental illnesses are not productive. One participant states: “Of course whenever we go with those students, the employers start to say these are not productive” (DPO Coordinator 4_>5 years experience). Another participant perceived employers’ insistence that students with mental illness are less productive as obstructive. He stated, “employers don’t have the right attitude” (TVET Coordinator 2_<5 years experience).

A lack of understanding explains this assumption according to another participant: “So even in most cases people do not […] understand that someone with mental condition can be productive, […] can be, like, trained, employed, […] this is related with understanding” (DPO Coordinator 3_>5 years experience). The biased perception of mental illness and its consequences for persons with mental disability are also highlighted:

…if you say you have intellectual disability then they will say this is a slow performer; […], and that kind of perception of course […] already lets people down. They don’t get a chance to really explore their potentials or to offer what potentials they have. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

The role of parents is described as ambiguous, ranging from being over-protective to the degree of denying their children their own rights to not being involved enough in the schooling of their children.

Regarding the over-protection, one participant mentions: “their family [of the persons with mental disabilities], have stopped them to go outside the community” (DPO Coordinator 4_>5 years experience). Another one adds: “Unlike other disabilities, parents tend to over-protect their children with mental disability. They feel they are the ones that can provide better protection and in protecting them, they […] are denying them their own human rights” (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience). Some families even prevent their children with mental illness from going to school. One participant explains:

Based on my experience, many people with mental or intellectual disability once they are born in a family they are not expected to go to school. […] Some have decided for them that they cannot manage so in most cases they do not have a chance to go to school. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

On the other hand, another participant states that some parents do not support their children enough: “The other problem [is] the lack of cooperation with the parents. The parents send their children with such kind of disability, they just leave you the student but there is no other follow up they do” (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience).

The beliefs and perceptions regarding mental illness were not only said to be common to employers, teachers, families, and communities but also to be internalised by the persons themselves. According to one participant, mental disability constitutes a large part of the self-concept of persons with mental disability. He describes how this can become problematic when the person seeks employment:

… when we place some student, they actually […] carry their disability along. So when they reach there, they really want to be seen as […] people with disabilities. Yet the employer is looking at you as an employee […] not as an employee with disabilities. So if you carry that ticket of disability then in most cases, they end up failing. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

Regarding the culture, mainly three pathways were suggested for how to increase the inclusion of persons with mental illness.

In response to the negative attitudes hindering inclusion of persons with mental disabilities, attitudinal changes among community members were described as pivotal. As a pathway, a strengths-based approach is suggested, in order for persons with mental disabilities to find their place in the labour market.

A participant mentioned that there is a need to better empower persons with mental disabilities and that more expertise is needed regarding how to do this:

[…] We have limited expertise in the country, in terms of how to empower the individuals with mental disability; from […] understanding them and knowing how to help them. (DPO Coordinator1_>5 years experience)

Another participant adds:

[…] they can be included just like any other person. It’s more of finding what they are good at and looking at what is out there in the market, and match them with what they can do, support them on the job [so that] eventually [they can] earn a living like any other person. (DPO Coordinator 1_>5 years experience)

Further, one participant suggested that the parents or guardians might also have an important role in advancing the chances of their children by explaining to the teachers their child’s disabilities, and advocating for their rights, to reduce stereotyping and discrimination:

So, if they explain to the teachers and say actually I live with this child at home, they are not violent and you only need to understand them. Then teachers can begin to adjust their fears and are able to accommodate them. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

In conclusion, a bottom-up strategy is proposed, starting with changed practices by those immediately involved, and supported by a wider expertise on mental illness, mental disability, and capacity on how to empower persons with mental disabilities.

Structure

The structure, i.e., regulations, laws, and policies at the level of organisations as well as at the state level, shaping and shaped by the culture and by practice, also present barriers and pathways. Rigid TVET curricula and admission requirements, inadequate teaching skills and lack of specialist support, as well as unclear school policies, are structural barriers to the inclusion of people with mental disability that participants identified. Pathways include providing guidance to the students, adaptive curricula and clearer policies.

The first barrier relates to the admission to TVET programmes. Admission is regulated by specific requirements, including primary school certificates. However, persons with mental disabilities often do not possess the required qualifications. As one respondent explains:

If you're going to start with lower level vocational training [i.e. TVET], at least you complete your primary education. But many of them do not even complete the primary education. They are just ignored at the start of their life. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

This structural barrier relates to the belief that persons with mental illness do not need to go to school and the practice of denying them access.

The second barrier concerns a reported misfit between the profiles of persons with mental disabilities and TVET curricula. The TVET programme comprises formal education and not only the acquisition of vocational skills. Participants observed some of the persons with mental illness or intellectual disability to be unable to meet the requirements of the TVET programme. One respondent pointed specifically to the inflexibility of the programme:

So, when it comes to public TVET, they are structured in such a way that students have to (go) through a curriculum that is not flexible. (DPO Coordinator 1_>5 years experience)

This is also related to teachers’ fear of students with mental illness, which, according to one participant, explains why there have not yet been any curriculum adaptations. He states:

Then the teachers fear them, they feel they cannot really teach them, so there has not been curriculum modification for them to fit in the mainstream training. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

A further structural barrier is that teachers are often ill-equipped to deal with students with mental disability. A lack of teacher training as well as specialist advice was mentioned numerous times. One respondent pointed out that teachers are not used to teaching this group of people:

Teachers are not trained for that kind of mental disability. They normally always teach people without disability and when you are including people with disability they cannot go on the same rate of teaching. (TVET Coordinator 2_<5 years experience)

The fact that TVET coordinators in many cases do not consider mental illnesses as disability constitutes the fourth structural barrier. An underlying reason has been found to be policies that are unclear regarding inclusion in TVET programmes. One respondent elaborates:

For us, the policy does not specify which kind of disability, they say disability in general, not […] the visual, or mental or hearing. No, the policy says only inclusive education for people with disabilities in general, they don't specify intellectual or learning disability. This is why the policy is not detailed, […], not specifying the category of disability. (DPO Coordinator 4_>5 years experience)

Regarding the structure, there were multiple proposals for how to overcome the barriers mentioned. Participants suggested how to determine a better fit between the individuals and the programmes offered and suggested several pathways towards inclusion. As one said, choosing the right programme is essential:

[…] So better to look for, at least to know, the kind of training that people with disability, mental disability can take. And the others cannot be attended by them. (TVET Coordinator 2_<5 years experience)

A study participant suggested it would be advantageous to make the curricula more flexible:

… you assess an individual, find out what this individual is interested in and instead of going through a full curriculum maybe tailor-make a curriculum specifically for specific groups of people. […] Where individuals like those with mental disability could be accommodated in TVET and be trained in a specific line of activity that they are interested in, and excel easily. (DPO Coordinator 1_>5 years experience)

In order to find a good fit, several participants proposed that there should be specific advisers within the programmes, some of whom had already been put that in place. One respondent explains:

Now, there is a career guidance given to the students before coming, before starting their training but […] at the time when we start[ed] this program [EmployAble], this kind of career guidance was not present. (DPO Coordinator 4_>5 years experience)

Similarly, another respondent described a “guiding and counseling centre”:

But under the EmployAble programme we've actually gone ahead especially in [my country] to establish an inclusive kind of guidance and counselling centre. We have tried to empower the counsellor […] to be able to actually take care of the students’ problems, including disability related. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

Teacher training is addressed as a pathway by several of the participants. One explained how specific teacher training could advance inclusion:

You really need to prepare them [the teachers] and have people who already have the skills to work with them [students with intellectual disability] to make them […] know that it’s possible, that these students can also learn. (DPO Coordinator 2_>5 years experience)

As another pathway towards better inclusion of persons with mental disability, a respondent proposed is a clear policy regulating who is eligible for participation in the programme. He states, “…if the laws can be specific on what they are talking about, I think that can also help the implementers to be guided on what exactly they need to do” (DPO Coordinator 3_>5 years experience). The last suggestion, again, refers back to the very definition of mental illness and the understanding of what it entails.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to explore the barriers and pathways to including persons with mental illness and intellectual disability in TVET programmes in four East African countries. We found that beliefs and attitudes form a culture of exclusion and segregation that is reflected in practices, such as not sending persons with mental disabilities to school or not employing them. Structural hurdles reinforce both the culture and the practice, e.g., TVET admission criteria that persons with mental disabilities often cannot meet and policies that do not clearly label mental illness and intellectual disability as a disability. As pathways, a more open and strengths-based attitude, tailor-made curricula, specific teacher training as well as clearer policies have been suggested.

The exclusion of persons with mental illness or intellectual disability cannot be reduced to a handful of independent causes that could be addressed directly. Rather, a complex net of factors influencing each other has been found to explain the exclusion. This has consequences for how best to tackle the problem.

The barriers identified here are entangled, complex, and persistent. Schuitmaker [Citation33] argues that problems are persistent when attempts to solve them are “worked against by features embedded in the […] system itself.” Persistent problems are produced and reproduced by the agents who shape and are shaped by culture and structure. As has been shown, the current culture and the structure are seriously hampering practices of inclusion of persons with mental illness or intellectual disability into TVET programmes.

In order to tackle persistent problems, simple solutions focusing only on one aspect are bound to fail [Citation34]. A system perspective is needed to envisage a way forward, in which multiple pathways are followed simultaneously and at different levels, mutually supporting each other. Changes in practice will induce changes in culture (albeit at the local level initially) and changes in policy will support changes in practice.

Based on the findings of this study, different pathways were identified that would support the inclusion of people with mental disability in TVET and hence support their employability (see ). Suggestions for the practice of TVET providers are to acquire expertise on mental disability; to acquire expertise on a strength-based approach to guiding students; to adjust training programmes to the needs of students; to support students through career guidance; and to match students’ individual capabilities with the needs of potential employers. Putting these suggestions into practice is expected to empower individuals and enable them to earn their living. Empowered individuals and changed practices together represent a belief in people with mental disabilities as unique individuals with diverse capacities and signifies a change away from a culture of stigmatizing people with mental disabilities as a group and regarding them as violent and unproductive. Policies will not only support the required changes in practice of current front-runners, but also stimulate others to follow suit, which, in turn, will affect the underlying system of beliefs towards a culture that is more conducive to disability-inclusive development.

Figure 2. Suggested recommendations for the practice of TVET providers and associated changes in structure and culture.

The pathways are intertwined and there is no clear starting point or a central steering power. Also, systems are relatively resistant to change, as they reproduce themselves and the structures that constrain them [Citation25]. From a system-innovation perspective, it is recommended to start where the energy is, with people who are willing to divert from the mainstream and dare to take risks [Citation35]. Even when policies are not conducive, professionals can find the room to maneuvre and employ rule flexibility, for instance to adjust training programmes to the needs of the students with mental disabilities [Citation35].

Individuals with mental disability are unique and possess skill sets that that are useful for their wellbeing and society at large [Citation5]. This understanding underpins the inclusive development movement and global efforts at inclusion [Citation36]. Disability-specific NGOs have a unique role to play as change agents to demonstrate that policies can be supported not only by national policy but also by NGOs [Citation37].

Understanding mental disability

An increased understanding of mental disability is pivotal to the various pathways. In this study, participants perceive intellectual disability as the same as mental disability. This classification is essential for persons with mental illness because it also affects their opportunities of employment and inclusion in TVET programme; especially in climes where person with intellectual disability are tagged slow learners and excluded from educational endeavours by persons without the relevant skill to teach them. Clear and precise definition of mental illness and definition of what constitutes mental disability has been a source of controversy [Citation38]. The pertinent lesson to note is that inaccurate and poor understanding boosts stigma and poor attitude towards persons with mental illness [Citation28,Citation39–41]. In a recent position paper issued by Users and Survivors of Psychiatry, Kenya, the authors urge policy makers to note the difference between mental illness and intellectual disability and avoid lumping both forms of disability together and making developmental plans difficult [Citation15]. At the same time, it has been argued that it is not as much the classification that is important, but the functional impairments that may have resulted from the mental illness or intellectual disability [Citation17]. Hence, educational institutions and employers need tools and human resources to assess at individual level functional impairments in relation to requirements of the profession they aspire, in order to be able to make reasonable accommodation.

Moreover, whereas theoretical paradigms have explicitly offered a multifaceted notion of disability, the societal perceptions of disability have not accommodated persons with mental illness [Citation26,Citation42,Citation43]. At the same time, although mental illness is included as a disability in the UNCRPD, many, including persons with mental disabilities themselves, do not recognise it as such and do not necessarily support it as it adds another layer of stigma [Citation18]. This dilemma, and that of disclosure to enable reasonable accommodation versus concealment and not being able to offer the right to adjustments [Citation44], will need to be debated more within the communities of persons with mental disabilities. This might also be a task for disability-specific NGOs and mental health organisations.

Limitations

It is pertinent to state that the small sample size of the participants limits the generalisation of the findings, that rely on expert opinion from TVET and DPO coordinators. Their observations reflect their lived experiences in their particular setting and are subject to their personal interpretations. For a more complete assessment of the situation, it would have been advantageous to include other groups of stakeholders, including TVET teachers, students with mental disability, community members, and policy makers.

Conclusions

Persons with mental illness or intellectual disability are largely excluded from TVET programmes and multiple underlying reasons have been identified. Most prominent is an attitude that legitimises exclusion from school and the labour market and policies that do not understand mental illness as a disability. Pathways suggested by participants are far-reaching and encompass diverse areas including attitudinal changes, adaptive curricula, and inclusive policies. These have been found to affect the culture and the structure and would be manifested in practices. For example, formulating an inclusive policy will probably change the admission criteria to TVET programmes and even the way for increased participation. At the same time, this would influence people’s perception of what mental illness entails and most likely also their attitude towards it and thus the direct interactions. If efforts are focused on culture and structure as underlying issues, they have the potential to induce system-wide change. Suggestions made by the coordinators of TVET and DPOs in the four East African countries are to be further clarified and implemented in the near future in order to enhance the chances of employment of persons with mental illness or intellectual disability.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Light for the World Netherlands for their support in this study and to all the study participants and their organisations in East Africa. We also thank the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript and Prof. dr. Jacqueline Broerse for reviewing the initial draft.

Presented as an abstract at the TransGlobal Health Annual Meeting, September 2017 (Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Vocational rehabilitation for severe mental illness. Treatment–refractory schizophrenia. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2014. p. 165–77.

- IncluD-ed. Inclusive Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in the context of lifelong learning: empowering people with disabilities with skills for work and life Spain: European network for inclusive education and disability (incluD-ed); 2015 [cited 2017]. Available from: http://includ-ed.eu/sites/default/files/documents/unesco_tvet_online_discussion_background_en.pdf

- van Ruitenbeek G, Mulder MJ, Zijlstra FR, et al. An alternative approach for work redesign: experiences with the method ‘Inclusive Redesign of Work Processes’ (Dutch abbreviation: IHW). Gedrag Organisatie. 2013;26:104–122.

- Yamamoto SH, Olson DL. Vocational rehabilitation employment of people with disabilities: descriptive analysis of US data from 2008 to 2012. J Appl Rehabil Counsel. 2016;47:3.

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol; 2006 [cited 2016]. Available from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- Mouzakitis GS. The role of vocational education and training curricula in economic development. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2010;2:3914–3920.

- Tripney JS, Hombrados JG. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) for young people in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Empir Res Vocat Educ Train. 2013;5:3–14.

- World TVET Database Kenya [Internet]. 2013. Available from: http://www.unevoc.unesco.org/wtdb/worldtvetdatabase_ken_en.pdf

- Abbott P, Wallace C, Sapsford R. Socially inclusive development: the foundations for decent societies in East and Southern Africa. Appl Res Qual Life. 2017;12:813–839.

- Murgor TK, Changa’ch JK, Keter JK. Accessibility of technical and vocational training among disabled people: survey of TVET institutions in North Rift Region, Kenya. J Educ Pract. 2014;5:200–207.

- International Labour Organisation. Inclusion of people with disabilities in Ethiopia; 2013 [cited 2017]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/skills/pubs/WCMS_112299/lang-n/index.htm

- Sanderson K, Nicholson J, Graves N, et al. Mental health in the workplace: using the ICF to model the prospective associations between symptoms, activities, participation and environmental factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1289–1297.

- Kennedy C. Functioning and disability associated with mental disorders: the evolution since ICIDH. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:611–619.

- Kamundia E. The right to the highest attainable standard of mental health in selected African countries: a commentary on how selected mental health laws fare against article 25 of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Afr Disabil Rts YB. 2017;5:179.

- Users and Survivors of Psychiatry Kenya. Advancing the rights of persons with psychosocial disability in Kenya. Kenya: USPKenya; 2017.

- Ebuenyi I, Syurina E, Bunders J, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of employment for people with psychiatric disabilities in Africa: a scoping review. Global Health Action. 2018;11:1463658.

- Linden M. Definition and assessment of disability in mental disorders under the perspective of the international classification of functioning disability and health (ICF). Behav Sci Law. 2017;35:124–134.

- Mulvany J. Disability, impairment or illness? The relevance of the social model of disability to the study of mental disorder. Sociol Health Illness. 2000;22:582–601.

- Khalema NE, Shankar J. Perspectives on employment integration, mental illness and disability, and workplace health. Adv Public Health. 2014;2014:1.

- Thoits PA. I’m not mentally ill: identity deflection as a form of stigma resistance. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57:135–151.

- Kirmayer LJ, Minas H. The future of cultural psychiatry: an international perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:438–446.

- Patel V. Explanatory models of mental illness in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1291–1298.

- Ruggeri M, Leese M, Thornicroft G, et al. Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:149–155.

- van Raak R. The transition (management) perspective on long-term change in healthcare. Transitions in health systems: dealing with persistent problems. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VU University Press, 2010. p. 49–86.

- Essink DR. Sustainable health systems: the role of change agents in health system innovation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VU University Press; 2012.

- Fernandes H, Cantrill S. Inclusion of people with psychosocial disability in low and middle income contexts: a literature and practice review. 2016. Available from: http://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/TEAR-MentalHealthReport_A4pg-FA_small_file_0.pdf

- Kett M. Skills development for youth living with disabilities in four developing countries. Background paper for EFA global monitoring report. Paris, France: UNESCO; 2012.

- van Niekerk L. Participation in work: a source of wellness for people with psychiatric disability. Work. 2009;32:455–465.

- UNESCO. Technical and vocational education and training for the twenty-first century: UNESCO and ILO recommendations. Paris, France: UNESCO; 2002.

- Maarse A. Report mid-term review employable program. Veenendaal, Netherlands: Light for the World Netherlands; 2015.

- Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley E. Qualitative methods in public health. San Francisco (CA): Jossey Bass; 2005.

- Muhr T, Friese S. User’s manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2004.

- Schuitmaker T. Persistent problems in the Dutch healthcare system: an instrument for analysing system deficits. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VU University Press; 2010.

- Schuitmaker TJ. Identifying and unravelling persistent problems. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79:1021–1031.

- van Veelen JS, Bunders AE, Cesuroglu T, et al. Child-and family-centered practices in a post-bureaucratic era: inherent conflicts encountered by the new child welfare professional. J Public Child Welfare. 2017;12:411–435.

- Heymann J, Stein MA, Moreno G. Disability and equity at work. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- van Veen SC. Development for all: understanding disability inclusion in development organisations. ‘s-Hertogenbosch: BOXPress; 2014.

- Mokoka MT, Rataemane ST, Dos Santos M. Disability claims on psychiatric grounds in the South African context: a review. S Afr J Psych. 2012;18:6–41.

- Beisland LA, Mersland R. Staff characteristics and the exclusion of persons with disabilities: evidence from the microfinance industry in Uganda. Disabil Soc. 2014;29:1061–1075.

- Eaton P. Preliminary findings of vocational training in Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey of outcomes and implications. WFOT Bull. 2008;58:10–16.

- van Niekerk L. Identity construction and participation in work: learning from the experiences of persons with psychiatric disability. Scan J Occup Ther. 2016;23:107–114.

- Staiger T, Waldmann T, Rüsch N, et al. Barriers and facilitators of help-seeking among unemployed persons with mental health problems: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:39.

- Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Bickenbach J, et al. The international classification of functioning, disability and health: a new tool for understanding disability and health. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:565–571.

- Nelissen P, Vornholt K, Van Ruitenbeek GM, et al. Disclosure or nondisclosure—Is this the question? Ind Organ Psychol. 2014;7:231–235.