Abstract

The subacute phase of low back pain has been termed as the “golden hour” to intervene to prevent work disability. This notion is based on the literature up to 2001 and is limited to back pain. In this narrative review, we examined whether the current literature indicate an optimal time for return to work (RTW) interventions. We considered randomized controlled trials published from 1997 to April 2018 assessing effects of occupational rehabilitation interventions for musculoskeletal complaints (15 included), mental health disorders (9 included) or a combination of the two (1 included). We examined participants’ sick leave duration at inclusion and the interventions’ effects on RTW. Most studies reporting an effect on RTW included participants with musculoskeletal complaints in the subacute phase, supporting that this phase could be a beneficial time to start RTW-interventions. However, recent studies suggest that RTW-interventions also can be effective for workers with longer sick leave durations. Our interpretation is that there might not be a limited time window or “golden hour” for work disability interventions, but rather a question about what type of intervention is right at what time and for whom. However, more research is needed. Particularly, we need more high-quality studies on the effects of RTW-interventions for sick listed individuals with mental health disorders.

The subacute phase of low back pain has been termed the “golden hour” for work disability prevention.

Recent evidence suggests there is a wider time-window for effective interventions, both for musculoskeletal- and common mental disorders.

A stepped-care approach, starting with simpler low-cost interventions (e.g., brief reassuring interventions), before considering more comprehensive interventions (e.g., multimodal rehabilitation), could facilitate return to work and avoid excessive treatment.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

In 2001, Loisel et al. [Citation1] suggested the subacute phase of low back pain to be the “golden hour” for work disability prevention. The basis for this suggestion was that most workers on sick leave recover in less than a month, whereas workers with longer absences were at considerably higher risk of persistent disability. The suggestion was also based on four intervention studies, which the authors considered promising at the time [Citation2–5]. The recently published Handbook of Return to work [Citation6] reinforced this suggestion, and in fact suggested intervening even earlier in a Best Practice recommendation: ‘Implementing intensive interventions at the beginning of the subacute stage (4–6 weeks), before disability and sickness absence become protracted, is likely the most effective’. This recommendation was backed up by papers published around the year 2000, as well as some clinical practice guidelines [Citation7,Citation8], not dealing with return to work (RTW) interventions specifically.

Since then, many more studies have been published on the effects of occupational rehabilitation and the scope has been broadened from low back pain to musculoskeletal complaints, and mental health problems, the other prevailing causes of sick leave [Citation9,Citation10]. Hence, in this narrative review, we sought to examine whether the current literature supports the notion of an optimal time for occupational rehabilitation, for the most common causes of sick leave.

Methods

In this narrative review, we included randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of occupational rehabilitation programs on RTW for sick listed workers with musculoskeletal complaints and/or common mental health disorders. We included studies where the intervention mainly targeted individuals who were sick listed, and not those that solely targeted sick leave prevention or presenteeism. We did not put any restrictions on the content of the programs as long as they contained more than one of the following: education, exercise/physical activity, stakeholder involvement, work-related problem solving/RTW-plan or a cognitive approach with RTW as the main goal. Thus, we did not include studies that only targeted a single component (e.g., only ergonomics or education).

As there is no consensus on how to measure RTW, we included both measurements of time spent working and sickness absence measures. Participants had to be sick listed for common mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, adjustment disorder) or musculoskeletal complaints. We did not include studies where participants were sick listed for musculoskeletal pain that were due to specific diseases like cancer-related pain and rheumatic inflammatory diseases. We searched PubMed, the reference lists of relevant articles, and contacted experts in the field. We included search terms like sickness absence, sick leave, RTW, occupational, musculoskeletal, pain, mental health, depression and anxiety. We only included studies written in English. Studies were included if they were published after the studies Loisel et al. [Citation1] included when suggesting the golden hour for work disability interventions, that is, from 1997 and up to April 2018. In addition, we included three of the four studies Loisel and co-workers included in their paper (the fourth was not a randomized trial [Citation4]).

Results

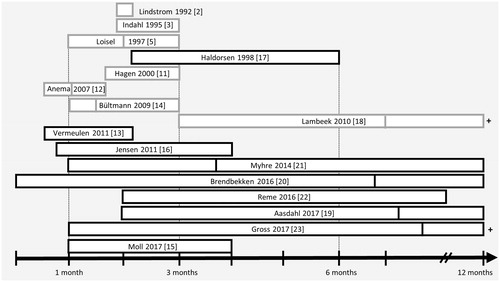

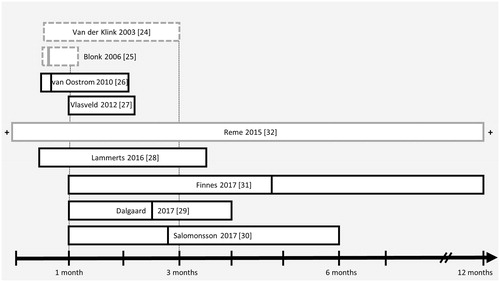

A total of 25 studies () met the eligibility criteria. Of these, 15 included participants with musculoskeletal complaints, while 9 recruited participants with common mental health disorders, and 1 study included both participants with musculoskeletal complaints and/or common mental health disorders.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Musculoskeletal complaints

See for included studies involving musculoskeletal complaints. The three randomized clinical studies Loisel et al. [Citation1] based their suggestion about the subacute phase being “the golden hour” to intervene were: Indahl et al. [Citation3], Lindstrom et al. [Citation2], and Loisel et al. [Citation5]. The study by Indahl et al. [Citation3], later corroborated by Hagen et al. [Citation11], found that a so-called “brief intervention” (a thorough examination by a physician, including reassurance and advice about staying active, and follow-up by a physiotherapist reinforcing the message), was more effective than usual care for participants with 8–12 weeks of sick leave. Lindstrom et al. [Citation2] evaluated the effect of a program consisting of a work place visit, back school education and graded activity for blue-collar workers on sick leave for 8 weeks. Participants in the program returned to work faster than those who received usual care. Finally, Loisel et al. [Citation5] compared usual care, a clinical intervention, an occupational intervention, and a combination of the latter two – later known as the Sherbrooke model. They included workers who had been sick listed for at least four weeks with back pain. The results of the study showed that participants who received the Sherbrooke model returned to work about twice as fast as those receiving usual care [Citation5]. However, there were only 22–31 participants in each arm.

Figure 1. Boxes indicate length of sick leave at inclusion in studies including participants with musculoskeletal disorders. The vertical line through the box indicate the median/mean sick leave duration, when reported. Grey outline on the box means that the study reported an effect on return to work, while black indicates it did not. A plus sign indicate inclusion beyond the time illustrated on the x-axis. The Aasdahl-study included both musculoskeletal complaints and mental health disorders.

The Canadian Sherbrooke model by Loisel and co-workers inspired several later studies. Anema et al. [Citation12] assessed the effect of a workplace intervention and graded activity, separately and combined. They found an effect for the workplace intervention on RTW, a negative effect for graded activity and no effect for the combined intervention. Participants in the study were sick listed 2–6 weeks due to low back pain. Vermeulen et al. [Citation13] found no effect of a participatory RTW-program for unemployed workers and temporary agency workers sick listed 2–8 weeks for musculoskeletal complaints. In contrast to the previous studies, they reported a slight delay in RTW for the intervention compared to usual care in the first 90 days of follow-up, but higher RTW in the following 9 months.

Several later studies have assessed occupational rehabilitation interventions in the subacute phase. Bültmann et al. [Citation14] included participants who had been sick listed 4–12 weeks due to musculoskeletal complaints, when they compared a coordinated and tailored work rehabilitation program to conventional case management. They reported that participants receiving the intervention had less sickness absence than those receiving usual care. Moll et al. [Citation15], however, found no difference in RTW rates between a multidisiplinary intervention and brief intervention for workers sicklisted 4–16 weeks due to neck or shoulder pain. Additionally, Jensen et al. [Citation16] reported similar RTW rates for hospital based multidisciplinary treatment and brief intervention for individuals sick listed 3–16 weeks due to low back pain. Haldorsen et al. [Citation17] also found no difference in RTW when they compared multimodal cognitive behavioral treatment to usual care for people sick listed with musculoskeletal complaints for 2–6 months.

In the past two decades, several occupational rehabilitation intervention studies have recruited participants with long-term sickness absence. Lambeek et al. [Citation18] included workers with low back pain sick listed for a median of 150 days, well beyond the subacute phase. They found that a program inspired by the Sherbrooke model consisting of integrated care management, a workplace intervention and graded activity was substantially more effective in facilitating RTW than usual care.

However, most studies including long-term sick listed workers have not found similar effects. Aasdahl et al. [Citation19] found no difference in sickness absence after a multicomponent occupational rehabilitation program versus outpatient Acceptance and commitment therapy – a recent form of cognitive behavioral therapy, in a study including participants with both musculoskeletal complaints and mental health disorders. The inclusion criterion was sick leave 2–12 months, with a median of 220 days median for those enrolled. Similarly, Brendbekken et al. [Citation20] found no difference in the time to full RTW when they compared a multidisciplinary intervention to brief intervention for individuals sick listed due to musculoskeletal complaints for less than 12 months. In a multicenter-study, Myhre, Marchand et al. [Citation21] found no difference in RTW when they compared work-focused rehabilitation to either a comprehensive multidisciplinary intervention or a brief multidisciplinary intervention for participants sick listed 1–12 months with neck or back pain. Similar findings were reported by Reme et al. [Citation22] for participants sick listed 2–10 months with low back pain; no difference in sick leave at 12 months of follow-up for brief intervention, a combination of brief intervention and cognitive behavioural therapy, brief intervention and seal oil, or brief intervention and soy oil. Finally, Gross et al. [Citation23] compared a rehabilitation program including motivational interviewing to traditional rehabilitation for sick listed workers with subacute or chronic musculoskeletal complaints. They found no difference in the total number of days receiving wage replacement benefits during 12 months of follow-up, but among job-attached workers they found less recurrence of benefits.

Mental health complaints

As can be observed in , substantially fewer studies investigated the effects of occupational rehabilitation for sick-listed individuals with mental health disorders than musculoskeletal complaints. In the subacute phase of sick leave, van der Klink et al. [Citation24] reported shorter sickness absence after an activating intervention versus usual care for individuals on sick leave for up to about 3 months due to an adjustment disorder. Blonk et al. [Citation25] found effects on RTW in favor of a combined workplace intervention and brief individual cognitive behavioural therapy compared to either only cognitive behavioral therapy or no treatment. They included self-employed individuals who reported sick due to work-related psychological complaints, such as anxiety and depression. The inclusion criteria for length of sick leave in the study was not clearly stated, but they stated that the interventions generally started 2–3 weeks after the workers reported sick.

Figure 2. Boxes indicate length of sick leave at inclusion in studies including participants with mental health disorders. The vertical line through the box indicate the median/mean sick leave duration, when reported. Grey outline on the box means the study reported an effect on return to work, while black indicates it did not. A dotted box indicate that the inclusion criteria of the study is not clear. A plus sign indicate inclusion beyond the time illustrated on the x-axis.

Several other studies recruiting persons with mental health disorders spanning the subacute phase of sick leave did not observe effects of various interventions. Van Oostrom et al. [Citation26] reported no difference between a workplace intervention and usual care in workers on sick leave for 2–8 weeks with distress. Similarly, Vlasveld et al. [Citation27] reported no effect for collaborative care including a workplace intervention versus usual care for individuals sick listed 4–12 weeks due to a major depressive disorder. Recently, Lammerts et al. [Citation28] observed no difference between a supportive RTW-program and usual care for workers sick listed 2–14 weeks without an employment contract. Dalgaard et al. [Citation29] reported a tendency for faster RTW when they compared work-focused cognitive behavioral therapy to clinical assessment or no intervention for individuals with work-related adjustment disorders sick listed for up to 4 months.

Salomonssen et al. [Citation30] found no difference in the number of sickness absence days between an RTW-program (consisting of early contact with the work place, identification of obstacles for RTW and creation of an RTW plan), CBT or a combination of the two for workers sicklisted 1–6 months for common mental health disorders. Similarly, Finnes et al. [Citation31] did not find an effect on RTW in a four armed trial comparing an Acceptance and commitment therapy intervention, a workplace dialogue intervention, a combination of the two, and usual care. They included workers sick listed 1–12 months (average 5) due to depression, anxiety- or exhaustion disorders.

In a recent study with a wide recruitment span, that is, from workers at risk of sick leave to participants absent from work for more than a year, Reme et al. [Citation32] found an effect on work participation for work-focused cognitive behavioral therapy and individual job support compared to usual care. Interestingly, the program was more effective for people on long term benefits.

Discussion

In the last two decades, several studies evaluating the effects of occupational rehabilitation for workers sick listed with musculoskeletal complaints have been published. Most interventions comprise different components and this heterogenity make comparisons across studies difficult. However, as displayed in , most of the studies on musculoskeletal complaints that found an effect on RTW included individuals sick listed about 1–3 months, supporting the claim by Loisel et al. [Citation1]; that this time-frame could be the “golden hour” for prevention of work disability. However, most of these studies share another feature: being inspired by the Sherbrooke model and thus include workplace interventions and coordination between stakeholders. This begs the question: could what you do be more important than when you do it? The study by Lambeek et al. [Citation18], also inspired by the Loisel-study, indicate that this could be the case, as an integrated intervention was highly successful in facilitating RTW for individuals on sick leave for about half a year with low back pain. The chronic phase has traditionally been seen as the most challenging phase, in which multidisicplinary treatments are less successful [Citation1]. However, Lambeek and co-workers demonstrate that this is not necessarily the case as they reported a hazard ratio of 1.9 for RTW and 82 vs. 175 sickness absence days during the follow-up year, in favor of integrated care compared to usual care. Also of note, Reme et al. [Citation32] found that the effect on RTW was largest for people on long-term benefits (>one year), when they compared integrated work-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with individual job support to usual care for persons with common mental disorders.

Many of the interventions described in the literature are complex, time-consuming and costly. Others, like brief intervention [Citation3], are less extensive. Therefore, it is not only a question of when to intervene, but also what type of intervention is needed at what time. The probability of RTW is quite high during the first weeks of sick leave before it gradually falls [Citation33,Citation34]. The literature also suggests that work disability becomes more complex over time, with a low correlation between pain and disability, and psycosocial factors playing a gradually more important role [Citation34]. Therefore, a stepped-care approach has been suggested; starting with simple, low intensity and low cost interventions, saving the more intensive interventions for those who need additional help [Citation35]. The subacute phase may be the appropriate time to start interventions, as suggested by Loisel et al. [Citation1], as the risk of long term disability has become high, and most spontanous recovery has occurred. This is also in line with a theoretical modelling study by van Duijn et al. [Citation36], which found 8–12 weeks of sick leave to be the optimal time for interventions. However, it should be noted that this study, utilizing data from available randomized studies, was published before the study by Lambeek et al. [Citation18], showing a very impressive effect on RTW of an integrated intervention in workers with low back pain on sick leave for about half a year.

So what kind of intervention is most appropriate at what time? Brief reassuring interventions have been effective in facilitating RTW in the early phases of sick leave due to low back pain [Citation3,Citation11], and are relatively inexpensive. The more complex interventions, inspired by the Sherbrooke model, have been shown to be effective both in the subacute and the chronic phases. As they are more comprehensive and costly, it might be more sensible to save them for people who struggle more to RTW. However, it has been suggested that just considering the duration of symptoms is too limited as a classification approach, and that there is a need for further subgrouping [Citation37,Citation38]. Different approaches, like psychological prognostic factors [Citation38,Citation39] and data driven trajectories [Citation37], have been suggested. Haldorsen et al. [Citation38] screened sick listed (>8 weeks) workers with musculoskeletal complaints into three groups according to their prognosis for RTW, before they, independently of the screening results, randomized the participants into three different treatment groups; usual care, light multidisiplinary treatment (similar to brief intervention) and intensive multidisiplinary rehabilitation. They found that none of the treatments provided an added effect on RTW for the good-prognosis group, while the more intensive treatment gave the best results for the group with a poor prognosis. For the medium-risk group, the intensive treatment gave no additional effect over the light treatment. The results of this study suggest this type of screening can be useful, but needs to be investigated more to establish its’clinical utility.

Most of the included studies on musculoskeletal complaints included participants with back pain. However, as individuals with low back pain often have pain in other areas as well [Citation40], the results might be transferable. Relatively few studies have evaluated the effect of occupational rehabilitation programs on RTW for individuals with mental health disorders (). However, at least in Norway, RTW-rates for sick listed workers are quite similar for people sick listed due to musculoskeletal complaints and mental health disorders [Citation41]. As the literature also indicate that factors associated with work disability are similar across disorders [Citation42,Citation43], knowledge from studies for musculoskeletal complaints might be transferable to mental health disorders. Still, more research is needed on the effects of occupational rehabilitation for people sick listed with mental health disorders.

We acknowledge some limitations. We did not systematically review the literature, but searched PubMed, the reference lists of relevant original research and systematic reviews on effects of occupational rehabilitation interventions for both musculoskeletal complaints and mental health disorders, and contacted several experts in the field. Furthermore, there was no written protocol for the literature search limiting reproducibility, and there is a possible selection bias. Furthermore, assessing length of sick leave is a challenge as people often alternate between being on and off sick leave. Participants’ history of sick leave is usually poorly described in articles, with only the most recent period of sick leave being considered. We suggest that future studies should include information about the total number of sick leave days for a longer period before inclusion, e.g., 12 months. Another challenge is comparing interventions when some studies compare the interventions to usual care, while other studies include a comparative treatment. When there are no effects on RTW for interventions that are compared to other treatments, it does not mean they are ineffective, just that they are not more effective than the comparative treatment. Finally, most of the studies included participants with employment. Helping people without an employment contract RTW is most likely harder, but very few studies included unemployed individuals making it hard to see a pattern.

In summary, the current literature lends some support to the suggestion that the subacute phase of sick leave is a beneficial time to start occupational rehabilitation for workers sick listed due to musculoskeletal complaints. However, recent studies suggest that occupational rehabilitation also can be very effective for people with longer sick leave durations. Our interpretation is that it is more relevant to consider what to offer when. In the subacute phase of sick leave, both simple and more complex multidisciplinary interventions have been successful. From a resource-perspective, it seems sensible to start with simpler low-cost interventions before considering interventions that are more comprehensive. This type of stepped-care approach would also reduce excessive treatment, which can prolong sick leave. However, where the cutoff between simple and complex interventions should be is not clear, and more research is needed. It is also a question about who needs what kind of treatment, and more work is needed to find good prognostic tools that are clinically useful. In addition, brief interventions, which have been shown to be effective in the subacute phase of sick leave due to low back pain, should be evaluated for other conditions as well (e.g., mental disorders). Future research should focus on stepped-care approaches to develop appropriate measures at different phases of sick leave and prognostic tools to early identify sick listed workers who need interventions that are more complex. Finally, more-high quality studies are needed on the effect of occupational rehabilitation for sick listed individuals with mental health complaints.

Acknowledgement

We thank Merete Labriola and Cecilie Røe for helping us develop the idea for this discussion paper.

References

- Loisel P, Durand MJ, Berthelette D, et al. Disability prevention: new paradigm for the management of occupational back pain. Disease Manage Health Outcomes. 2001;9:351–360.

- Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, et al. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomized prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Phys Ther. 1992;72:279–290; discussion 91-3.

- Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine. 1995;20:473–477.

- Yassi A, Tate R, Cooper JE, et al. Early intervention for back-injured nurses at a large Canadian tertiary care hospital: an evaluation of the effectiveness and cost benefits of a two-year pilot project. Occup Med (Lond). 1995;45:209–214.

- Loisel P, Abenhaim L, Durand P, et al. A population-based, randomized clinical trial on back pain management. Spine. 1997;22:2911–2918.

- Schultz IZ, Chlebak CM, Law AK. Bridging the gap: evidence-informed early intervention practices for injured workers with nonvisible disabilities. In: Schultz IZ, Gatchel RJ, editors. Handbook of return to work. Boston: Springer; 2016. p. 223–253.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–491.

- Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34:1066–1077.

- Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration statistics. NAV disability pension statistics. 2015. [accessed 2016 Jan 4]. https://www.nav.no/no/NAV+og+samfunn/Statistikk/AAP+nedsatt+arbeidsevne+og+uforetrygd+-+statistikk/Uforetrygd.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196.

- Hagen EM, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain? Spine. 2000;25:1973–1976.

- Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32:291–298; discussion 299-300.

- Vermeulen SJ, Anema JR, Schellart AJ, et al. A participatory return-to-work intervention for temporary agency workers and unemployed workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:313–324.

- Bultmann U, Sherson D, Olsen J, et al. Coordinated and tailored work rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial with economic evaluation undertaken with workers on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. J Occupat Rehabil. 2009;19:81–93.

- Moll LT, Jensen OK, Schiottz-Christensen B, Stapelfeldt CM, Christiansen DH, Nielsen CV et al. Return to work in employees on sick leave due to neck or shoulder pain: a randomized clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary and brief intervention with one-year register-based follow-up. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:346–356.

- Jensen C, Jensen OK, Christiansen DH, Nielsen CV. One-year follow-up in employees sick-listed because of low back pain: randomized clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary and brief intervention. Spine. 2011;36:1180–1189.

- Haldorsen EM, Kronholm K, Skouen JS, Ursin H. Multimodal cognitive behavioral treatment of patients sicklisted for musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;27:16–25.

- Lambeek LC, van Mechelen W, Knol DL, et al. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. BMJ. 2010;340:c1035.

- Aasdahl L, Pape K, Vasseljen O, et al. Effect of inpatient multicomponent occupational rehabilitation versus less comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation on sickness absence in persons with musculoskeletal- or mental health disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:170–179.

- Brendbekken R, Eriksen HR, Grasdal A, et al T. Return to work in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: multidisciplinary intervention versus brief intervention: a randomized clinical trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:82–91.

- Myhre K, Marchand GH, Leivseth G, et al. The effect of work-focused rehabilitation among patients with neck and back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2014;39:1999–2006.

- Reme SE, Tveito TH, Harris A, et al. Cognitive Interventions and Nutritional Supplements (The CINS trial): a randomized controlled multicentre trial comparing a brief intervention with additional cognitive behavioural therapy, seal oil, and soy oil for sick-listed low back pain patients. Spine. 2016; 41:1557–1564.

- Gross DP, Park J, Rayani F, et al. Motivational interviewing improves sustainable return to work in injured workers after rehabilitation: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:2355–2363.

- van der Klink JJ, Blonk RW, Schene AH, van Dijk FJ. Reducing long term sickness absence by an activating intervention in adjustment disorders: a cluster randomised controlled design. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:429–437.

- Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioral interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work Stress. 2006;20:129–144.

- van Oostrom SH, van Mechelen W, et al. A workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with distress: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:596–602.

- Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Ader HJ, et al. Collaborative care for sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder: a randomised controlled trial from the Netherlands Depression Initiative aimed at return to work and depressive symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:223–230.

- Lammerts L, Schaafsma FG, Bonefaas-Groenewoud K, et al. Effectiveness of a return-to-work program for workers without an employment contract, sick-listed due to common mental disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42:469–480.

- Dalgaard VL, Aschbacher K, Andersen JH, Glasscock DJ, Willert MV, Carstensen O et al. Return to work after work-related stress: a randomized controlled trial of a work-focused cognitive behavioral intervention. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2017;43:436–446.

- Salomonsson S, Santoft F, Lindsater E, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and return-to-work intervention for patients on sick leave due to common mental disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:905–912.

- Finnes A, Ghaderi A, Dahl J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and a workplace intervention for sickness absence due to mental disorders. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017. DOI:10.1037/ocp0000097

- Reme SE, Grasdal AL, Lovvik C, et al. Work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support to increase work participation in common mental disorders: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72:745–752.

- Frank JW, Brooker AS, DeMaio SE, et al. Disability resulting from occupational low back pain. Part II: What do we know about secondary prevention? a review of the scientific evidence on prevention after disability begins. Spine. 1996;21:2918–2929.

- Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine. 1987;12:632–644.

- Waddell G, Burton AK, Kendall NA. Vocational rehabilitation–what works, for whom, and when? Report for the Vocational Rehabilitation Task Group. London: TSO; 2008.

- van Duijn M, Eijkemans MJ, Koes BW, et al. The effects of timing on the cost-effectiveness of interventions for workers on sick leave due to low back pain. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:744–750.

- Kongsted A, Kent P, Axen I, et al. What have we learned from ten years of trajectory research in low back pain? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:220.

- Haldorsen EM, Grasdal AL, Skouen JS, et al. Is there a right treatment for a particular patient group? Comparison of ordinary treatment, light multidisciplinary treatment, and extensive multidisciplinary treatment for long-term sick-listed employees with musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2002;95(1–2):49–63.

- Hay EM, Dunn KM, Hill JC, et al. A randomised clinical trial of subgrouping and targeted treatment for low back pain compared with best current care. The STarT Back Trial Study Protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:58.

- Hagen EM, Svensen E, Eriksen HR, et al. Comorbid subjective health complaints in low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:1491–495.

- Nossen JP, Brage S. Forløpsanalyse av sykefravaer:når blir folk friskmeldt? Arbeid og velferd. 2016;3:75–100.

- Briand C, Durand MJ, St-Arnaud L, Corbiere M. Work and mental health: learning from return-to-work rehabilitation programs designed for workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30(4–5):444–457.

- Shaw WS, Kristman VL, Vézina N. Workplace issues. In: Loisel P, Anema J, editors. Handbook of work disability. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 163–182.