Abstract

Purpose: Persons with a developmental disability have the lowest rate of labour force participation relative to other disabilities. The widening gap between the labour force participation of persons with versus without disability has been an enduring concern for many governments across the globe, which has led to policy initiatives such as labour market activation programs, welfare reforms, and equality laws. Despite these policies, persistently poor labour force participation rates for persons with developmental disabilities suggest that this population experiences pervasive barriers to participating in the labour force.

Materials and methods: In this study, a two-phase qualitative research design was used to systematically identify, explore and prioritize barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities, potential policy solutions and criteria for evaluating future policy initiatives. Incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives, a Nominal Group Technique and a modified Delphi technique were used to collect and analyze data.

Results: Findings indicate that barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities are multi-factorial and policy solutions to address these barriers require stakeholder engagement and collaboration from multiple sectors.

Conclusions: Individual, environmental and societal factors all impact employment outcomes for persons with developmental disabilities. Policy and decision makers need to address barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities more holistically by designing policies considering employers and the workplace, persons with developmental disabilities and the broader society. Findings call for cross-sectoral collaboration using a Whole of Government approach.

Persons with a developmental disability face lower levels of labour force participation than any other disability group.

Individual, environmental and societal factors all impact employment outcomes for persons with developmental disabilities.

Decision and policy makers need to address barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities holistically through policies guiding employers and broader societal behaviour in addition to those aimed at the individuals (such as skill development or training).

Due to multi-factorial nature of barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities, policy solutions are wide-ranging and fall under the responsibility of multiple sectors for implementation. This calls for cross-sectoral collaboration using a “Whole of Government” approach, with shared goals and integrated responses.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Persons with disabilities are at a higher risk of exposure to challenging living and working conditions associated with poorer health outcomes such as lower income and greater employment insecurity [Citation1–3]. Employment provides an opportunity for financial autonomy and plays a key role in the well-being and quality of life of persons with disabilities [Citation4]. Inclusion of the neurodiverse population in the workplace is a largely untapped talent pool, which can provide a competitive advantage to employers who can appreciate the business case for inclusion [Citation5].

The widening gap between the labour force participation of persons with versus without developmental disabilities has been an enduring concern for many governments across the globe. This concern has led to policy initiatives such as labour market activation programs, welfare reforms, and equality laws [Citation6,Citation7]. Like many countries, Canada has mechanisms in place to protect the rights of persons with disabilities to participate in the labour force [Citation7,Citation8]. This includes existing legislation and policy such as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canadian Human Rights Act, and Employment Equity Act as well as being a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Implementation, however, has been inconsistent, resulting in disjointed policy and uneven states of accessibility, responsiveness and affordability [Citation7].

Canadians with developmental disabilities face lower rates of labour force participation than any other disability group in the country [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. In 2011, the employment rate of Canadians with disabilities aged 25–64 years was 49%, compared with 79% for those with no disability [Citation11]. While employment rates among persons with disabilities vary by type of disability, in Canada, persons with developmental disabilities have the lowest employment rate (24%) [Citation7,Citation9]. Beyond the economic impacts for this group, being unemployed also eliminates the associated non-income benefits of participation in the labour force (e.g., social inclusion, community involvement) while also limiting eligibility for work-triggered income or insurance programs [Citation9]. This corroborates with a worldwide trend, where paid employment for persons with developmental disabilities is very low, ranging from 9% to 40% across different countries [Citation12,Citation13].

Despite rights-based legislation, poor employment rates suggest that persons with developmental disabilities experience pervasive barriers to participating in the labour force [Citation9,Citation10]. Barriers to employment have been defined as “events or conditions, either within the person or in his or her environment, that make career progress difficult” [Citation14,p.434]. Specific to persons with developmental disabilities, barriers to employment have been reported as both individual (or personal) and external (or environmental) challenges [Citation15]. Individual (or personal) barriers include relationship and social skills difficulties [Citation16–19]; impairments in verbal and nonverbal communication [Citation12,Citation20,Citation21] and difficulty with changes in routine [Citation15,Citation22]. The most common external (or environmental) barriers include employer characteristics (e.g., type of business, size, location) and employment setting policies and practices [Citation23,Citation24]; employers’ attitudes and misconceptions [Citation12,Citation13,Citation24–28]; work setting [Citation12]; perceived costs of accommodation [Citation23,Citation29,Citation30]; low family expectations [Citation17,Citation31] and stigma [Citation32,Citation33]. Much of this work on barriers is descriptive in nature. None of these studies have prioritized barriers and solutions to employment for persons with developmental disabilities from the perspective of multiple stakeholders.

In this study, a two-phase research design was used to systematically identify, explore, and prioritize barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities, potential policy solutions, and criteria for evaluating future policy initiatives from the viewpoint of diverse stakeholders. First, the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) [Citation34] was used to identify and rank order the salience of barriers for individuals with developmental disabilities to participating, and sustaining their participation, in the labour market. Second, the potential policy solutions to overcome these barriers were identified utilizing the Delphi technique[Citation35]. Criteria were also identified with this method to guide the evaluation of the identified policy solutions as well as future policy initiatives.

Few studies to date have employed a multi-stakeholder qualitative approach. Most of the previous research on employment for persons with developmental disabilities has been driven by survey or population data [e.g., Citation9,Citation27,Citation36–41] or from the perspective of a single stakeholder group [Citation24,Citation27,Citation42–44]. A better understanding of barriers relative to persons with developmental disabilities and employment from the multiple perspectives of a diverse group of stakeholders helps to inform future policies in the area of inclusive employment as well as to aid direct efforts to create more appropriate supports and resources.

Methods

Study design

To better understand the experiences and barriers pertaining to employment for persons with developmental disabilities, a one-day event was held with diverse stakeholders in June 2017 to collect data for analysis. This event employed two participatory qualitative research methods: the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) [Citation34] and a modified Delphi technique [Citation35]. Completed during the event, the NGT entailed stakeholders identifying, exploring and rank ordering barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities. A modified three-step Delphi technique was initiated during the event and completed online to establish consensus on potential policy solutions to overcome the identified barriers as well as to develop effective criteria for evaluation of the identified policies. A follow up focus group was held with persons with developmental disabilities (N = 5) so as to further the discussion on key points as well as understand their perspective on the prioritized barriers and solutions reached during the NGT and Delphi technique

Participant recruitment, sampling and arrangement

Event participants were identified as stakeholders, boundary spanners, gatekeepers, knowledge brokers, or leaders in the field using both purposeful and convenience sampling approaches based on the experience of the researchers within the disability community. Thirty-one stakeholders were recruited from six distinct categories: 1) persons with developmental disabilities and their families/caregivers (N = 5), 2) employers (N = 3), 3) vocational training professionals (N = 3), 4) non-profit organizations and other disability serving organizations (N = 5), 5) decision and policy makers (N = 5), and 6) researchers and academics (N = 10). All participants were individuals experienced in working with, employing, or caring for individuals with developmental disabilities or those with lived experience. Fifty five percent of our participants were female and 45% were male.

Contained with the first category were family members/caregivers (N = 4) and persons with a developmental disability (N = 1). Families and caregivers were engaged both through their caregiver perspective and as proxies for persons with developmental disabilities. Persons with developmental disabilities represent a heterogeneous population that makes their identification and recruitment in research difficult [Citation45–48]. To enhance our chance of having a stronger voice from this stakeholder group we decided to include their families and caregivers as proxies as they are the key source of support and are aware of the daily challenges of this population group [Citation49]. In addition, there were participants wearing more than one hat that contributed information on behalf of their family members (N = 2). These individuals were counted in reference to their primary stakeholder groups and not included in the total count for category one. None of the individuals present were related to one another. Inclusion criteria focused on individuals who were engaged in supporting, providing services to, or developing policy for persons with developmental disabilities. Exclusion criteria were specific to persons who could not provide full informed consent and whose place of residence was outside, and/or work focused beyond, the geographic and policy catchment region of Alberta, Canada.

To recruit participants for the focus group following the event, we recruited only persons with developmental disabilities not their families/caregivers (N = 5) through a third-party disability organization gatekeeper. The research team was invited to present findings from the event to a group of clients of this gatekeeper organization, which helped build trust and access to research participants.

Nominal Group Technique

The NGT was employed to enable participants to generate a wide range of ideas concerning barriers to employment of persons with developmental disabilities. NGT was introduced by Delbecq and Van de Ven [Citation34] as a process to identify, and develop appropriate solutions to solve, strategic problems [Citation50]. NGT is a stepwise consensus-building democratic process to develop a list of collective priorities [Citation51]. This approach was well suited to address our research questions as this method offers an equivalent voice to each member and allows them to equally contribute to group discussions [Citation52]. This was important for engaging a diverse group of participants with a potential power imbalance.

Use of the NGT has many advantages compared to other group techniques [Citation53], including dissuading idea domination by more vocal or powerful members of the group [Citation54]; efficiency in terms of using few resources to collect a significant amount of information in a short time and over a single occasion [Citation52]; and participant satisfaction as a result of requiring little preparation and allowing for immediate dissemination of results [Citation53].

We used an adapted version of the NGT that entails five steps: silent generation, round robin engagement, clarification, categorization and ranking [Citation53]. Stakeholders were pre-assigned to four groups based on their category/group identification (e.g., policy/decision maker, employer, family/caregiver, etc.). Groups consisted of a combination of individuals from stakeholder categories and contained 6–8 participants each. This number is generally recommended for focus groups to optimally allow for diversity of perspectives to be represented yet also easy exchange of ideas [Citation55]. The NGT process was facilitated by an experienced professional organizer (lead facilitator). Each table has a facilitator (trained by the lead facilitator prior to the event) as well as a note taker. The roles of the lead and table facilitators were critical, especially in providing clear explanations of the group goal, promoting purposeful interactions between group members and helping participants to feel at ease [Citation56]. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to participating in the event and the project was reviewed and approved by the local university research ethics board.

The NGT process lasted approximately two hours. The purpose of this technique was to draw from the knowledge and expertise of stakeholders and allow them to contribute to the analytic process through the clustering and prioritizing of generated ideas. NGT sessions are not normally audio-recorded and transcribed as participants’ ideas (i.e., verbatim responses) are written on a flipchart which provides a concise summary of the session [Citation50]. Notes were only taken during group discussions.

Delphi technique

A modified three-step Delphi technique was used to identify and rank order policy solutions to overcome the identified and prioritized barriers to employment for persons with DD as well as criteria to evaluate these policies. The Delphi approach has been demonstrated to be an effective tool in obtaining consensus among different stakeholders who are based in different locations [Citation35]. A modified Delphi approach was initiated through an in-person brainstorming practice followed by two rounds of online survey. Unlike NGT, the Delphi does not require research participants to interact with each other to establish consensus, but instead provides participants with an equal opportunity to provide their input and feedback anonymously and directly [Citation57].

The first step (i.e., brainstorming) was completed in person following the NGT. Within groups, participants brainstormed potential policy solutions to overcome the prioritized barriers, and then, criteria to evaluate those policies. These policy solutions and criteria were used to develop an online survey, the second step of the Delphi technique. In this survey participants were asked to rate the importance of each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5). As the survey was self-administered, participants were able to answer without the risk of them influencing one another’s responses. At the end of the first round of the online survey, standard descriptive statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS. To describe the importance rating of each item, the mean score, as a measure of central tendency, was used. We established a consensus point of 80% meaning that if an item received greater than 80% of participants’ vote (at least 80% of the responders agreeing or strongly agreeing with an item), it was prioritized as a policy solution or criterion [Citation58–60]. These ordered items were compiled and included in the second round of the online survey (the third step of the Delphi).

Four weeks after completing the second step of the Delphi (the first round of the online survey), the third and final step of the Delphi was initiated (the second online survey) with the same population of participants. This survey included the policy solutions and criteria that received greater than 80% of participants’ agreement during the first round. From these, participants were asked to prioritize and rank order the top five policy solutions in terms of perceived importance in addressing existing gaps and delivering effective, efficient, and equitable services for persons with developmental disabilities. Participants were asked to do the same for the top five criteria for assessing the adequacy of policies, based on the perception of impact on employment accessibility and inclusion for persons with developmental disabilities. This iterative process allowed participants to re-evaluate and re-consider their views in light of aggregated results.

Focus group

Focus groups constitute a qualitative research method using group discussions to explore a particular issue [Citation55,Citation61]. It is defined as a group of individuals gathered by researchers to discuss the topic of research from personal experience [Citation63]. Focus group discussions provide a platform to explore the perspectives of people who share common experiences [Citation62,Citation63]. To better understand the perspectives of persons with developmental disabilities on the prioritized barriers and solutions reached during the NGT and Delphi technique, the focus group was considered the most appropriate data collection method. The key objective of this focus group was to have participants expand on the barriers with their labour market experiences while providing important context to the feasibility, applicability, and suitability of policy solutions discussed. The focus group discussions were structured around the key findings of NGT and Delphi (i.e., semi-structured discussions).

The focus group was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Focus group data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach [Citation61,Citation64]. In analyzing the data, we took into consideration not only the views of focus group participants on NGT and Delphi findings but also how they developed their arguments and negotiated issues in question.

Results

Barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities

A total of 140 barriers were generated by four groups in the first phase of the NGT. The top three barriers were collected from each group (a total of 14 barriers), which reflected the number of points (strength of priority ranking) assigned by participants during the NGT (). We then presented these 14 barriers on a flipchart and asked all participants (N=31) to select the top three as being the three priorities of the entire group.

Table 1. Top three barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities indicated by each group during the Nominal Group Technique.

From the top 14 challenges identified in , stakeholders prioritized and reached consensus on the top three barriers in participating or sustaining participation in the labour market for persons with developmental disabilities:

Employers’ knowledge, capacity, attitudes, and management practices,

Late start to the “concept of work” and workplace culture education, and

Stigma.

Employers’ knowledge, capacity, attitudes, and management practices

Employer-related factors received the highest consensus among participants. During the NGT group discussions, participants identified several employer-related barriers. It was noted that many employers have limited understanding of developmental disabilities and how to support a person with developmental disabilities in terms of challenges that they may face in the workplace. This can lead to poor hiring and management practices that present, among others, limited flexibility in recruiting processes and adapting tasks and other work-related activities. Participants emphasized that employers tend to not optimally capitalize on the skillsets of persons with developmental disabilities in the workplace, presenting a missed opportunity. For example, a participant stated, “… they [persons with developmental disabilities] are good at certain skills and employers who take advantage of these skillsets make these people happy and benefit themselves too.” Group 2

Participants identified a range of myths and misconceptions of employers related to the skills and abilities (or lack thereof) of persons with developmental disabilities, with implications for their view of the individual’s capacity to work. These misconceptions were argued to lead employers to associate employment-related risks, such as safety risks, with persons with developmental disabilities. Examples of such perspectives are offered in the statements recorded during the NGT group discussions:

“… they [employers] look at these people’s [persons with developmental disabilities] abilities, thinking that they are not able to do the job.” Group 2

“They [employers] think she/he [person with a developmental disability] is the liability of the company…running into hazardous circumstances.” Group 4

The concern about the perceived cost of accommodations for persons with developmental disabilities was identified as a limiting and negative attitude among employers. Employers’ perceived loss of profit and productivity was another barrier. According to participants, employers reportedly perceive that hiring a person with developmental disabilities decreases their overall productivity and increases their cost of supervision. For example, typical work environments can prove challenging for persons with developmental disabilities as some prefer to work in a quiet workspace or with limited interactions with others. This can be difficult in many collaborative or open-concept workplaces. It was emphasized that accommodations for the environment not the ability to complete tasks were often the issue.

Along with such workplace structures, participants described a range of processes that may impede employment success for adults with developmental disabilities. Hiring practices and stigma among employers were concerns. Participants suggested that stigma is the result of employers’ lack of knowledge and understanding of developmental disabilities as well as fear of the unknown. Stigma was believed to lead to discrimination, especially if an employer had a past negative experience of employing a person with developmental disabilities, as illustrated below:

“An employer who doesn’t know how to hire someone with autism, or how to interact with them, or how to handle their daily issues or how to accommodate them without being disrespectful, prefer to avoid these issues…” Group 1

It was emphasized that persons with developmental disabilities experience discrimination associated with their condition. For example, traditional interview styles or phone interviews prove difficult for persons with developmental disabilities, especially when applicants must decide whether or not to disclose their disability. This can serve to inhibit an individual from a successful interview, regardless of whether they have the technical skills and/or expertise for the job. See sample quote below from the focus group held with persons with developmental disability.

“…because of my inability to either perform on a phone interview and I have auditory processing issues and I struggle very much with the phone. I basically, I don’t use the telephone, period. And with so many employers starting the process with a phone interview, it pretty much predetermines failure. Now I’ve done the phone interviews, I’ve tried my best with the phone interviews, I’ve gone into quiet rooms with volume cranked, you know, I’ve got an expensive pair of noise cancelling headphones.” Focus Group

Late start to the “concept of work”

Participants suggested that, relative to counterparts without disabilities, persons with developmental disabilities had later access to vocational training. This was viewed to obstruct their development of vocational skills which in turn limits their access to and maintenance of employment. Reported key vocational skill challenges impacting these individuals were described to include a lack of adaptability to change, difficulty with new tasks, or deviation from routines. Participants largely held secondary schools (high schools) responsible for the late exposure of these individuals to the “concept of work” and workplace culture. There were also arguments that greater focus should be placed on enhancing employability and vocational training:

“… they [persons with developmental disabilities] start too late to enter the job market and they receive limited information about workplace culture at high school; so you can’t expect them to have enough work experiences.” Group 1

Limited vocational training to prepare persons with developmental disabilities to successfully enter the job market and limited sustained training to maintain positions were among limiting factors impeding optimal workplace outcomes. It was argued that job coaching, among other supports, helps persons with developmental disabilities understand social nuances at a workplace as well as learn workplace norms and rules.

Stigma

Stigma is a broad concept that can be present in the workplace or more broadly in society. While both impact employment outcomes, stigma in the workplace is captured in the first barrier described above. However, stigma, prejudice, and negative perceptions present in society more broadly and inherent in some programs and services can impact an individual’s ability to do the work-related tasks they are capable of completing. Disincentives to working present in income support programs, limitations in accessibility for completing activities of daily living, transportation challenges, and adverse public perception are all components inherent in limitations in society. An example provided by participants was the disincentives for individuals with a developmental disability to enter the workforce once they receive Alberta’s income assistance program called Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH). Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped provides a disincentive for many individuals to enter the workforce as those who supplement their benefits through paid employment often see little benefit from doing so due to earning exemptions and the potential loss of health and/or dental benefits [Citation65].

Policy solutions and criteria

During the event, participants identified 28 policy solutions and 33 criteria which shaped the content of the first online survey (see Supplementary Table S1 for full list of policy solutions and criteria). During the first round of the online survey, 15 policy solutions and 17 criteria received greater than 80% of participants’ votes (Supplementary Table S2). These policy solutions and criteria were included in the third and final round of the Delphi (the second round of the online survey), whereby the top five policy solutions and criteria were extracted ().

Table 2. Top five policy solutions and criteria extracted from the final step of the Delphi.

Discussion

The use of the Nominal Group Technique and Delphi qualitative techniques successfully yielded the identification and prioritization of barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities and potential policy solutions to address these barriers. Criteria were also generated and consensus was reached among diverse stakeholders in terms of their ability to evaluate the policy solutions identified. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind. The diverse engagement of decision makers, persons with developmental disabilities and their families/caregivers, employers, vocational training professionals, non-profit and other disability serving organizations, and researchers and academics strengthen the recommendations for policy direction regarding employment for persons with developmental disabilities.

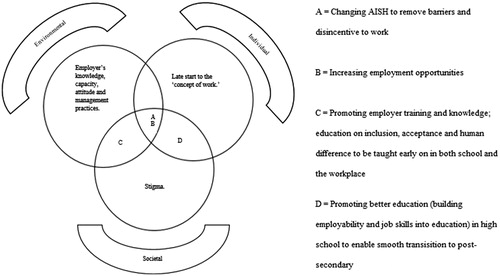

Consensus was reached on the top three barriers to participating or sustaining participation in the labour market for persons with developmental disabilities. These barriers () are observed as being external (environmental or societal) as well as internal (individual) in nature. The top barrier, related to employers, is external (environmental) in nature, while the second barrier (late start to the “concept of work”) is more individual (personal) and related to persons with developmental disabilities and their families/caregivers. The third barrier, stigma, is also external (environmental), but related to society at large. It is important to note that participants looked at stigma from the perspective of both employers and broader society. These results emphasize the perspective that individual, environmental, and societal factors all impact employment outcomes for persons with developmental disabilities. This is in contrast to much of the literature on the topic that focuses on skill development and vocational training opportunities [Citation66–68]. Success in employment appears to reflect a combination of individual characteristics and external factors (e.g., education, the work environment, management practices, employers’ attitude) that interact in a complex manner to either contribute to or impede successful employment [Citation66]. Our findings are in line with the ecosystem approach to employment for persons with developmental disabilities [Citation69], which considers a wide range of individual and external factors (e.g., family, agencies, community, workplace) contributing to the employment outcome for this population group. The key groups with an integrative role within the broader employment ecosystem include persons with developmental disabilities and their families/caregivers, the workplace, broader community, vocational support services, and a supportive policy infrastructure [Citation66,Citation69,Citation70].

Figure 1. The top three challenges and associated policy solutions, grouped according to their areas of influence.

This study indicates that workplace-related factors are deemed a high priority. Building on this emphasis, policy solutions that received the highest priority by participants in this study were mostly geared toward employers (). This finding is particularly notable as much of the literature on employment for persons with developmental disabilities has focused on the development of vocational skills or provision of supportive employment opportunities [Citation66–68,Citation71]. A review of the literature on 21 vocational interventions for adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) found that about half of the interventions had a focus on jobs tasks, with few related to job retention, employer knowledge, or workplace environment. In addition, many of the interventions were confined to certain contexts and with limited generalizability across settings [Citation72]. Supported employment can be instrumental in helping individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder gain entry to the workforce and maintain their position [Citation67,Citation73–77]. Similarly, education and training during the transition from secondary school to adulthood is a particular area of focus for improving employment outcomes [Citation78–83]. While our study supports these findings, it is important to note that consideration for societal and workplace related capacity is an important priority that appears to be lacking. Notably, a recent study suggests that capacity-building broadly in employment support for youth and adults with developmental disabilities is recommended due to a lack of evidence guiding existing employment services [Citation70].

The policy solutions identified in this study interact broadly with one another to address several of the main barriers to participation or sustaining participation in the labour market for persons with developmental disabilities (). These policy solutions consider a more holistic approach in terms of targeting policies at employers, persons with developmental disabilities, and broader society. For example, the policy solutions that would serve to address external barriers (both in terms of the employer as well as stigma) include the promotion of employer training and knowledge and education on inclusion, acceptance, and human difference to be taught early on in both school and the workplace (). Promoting better education (building employability and job skills into education) in high school to enable smooth transition to post-secondary or employment is a policy solution that would address one of the individual barriers identified (late start to the “concept of work”) as well as overall societal stigma (). Increasing employment opportunities was discussed as a top policy solution, which works to address each of the top three barriers to employment discussed. As can be seen in the overlap, increasing employment opportunities serves to effectively work on the environmental, individual, and societal barriers mentioned (). Similarly, changing Alberta’s Income assistance plan, Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH), to remove barriers and the disincentive to work addresses the top three individual and environmental barriers by both empowering the individual and reducing external restrictions ().

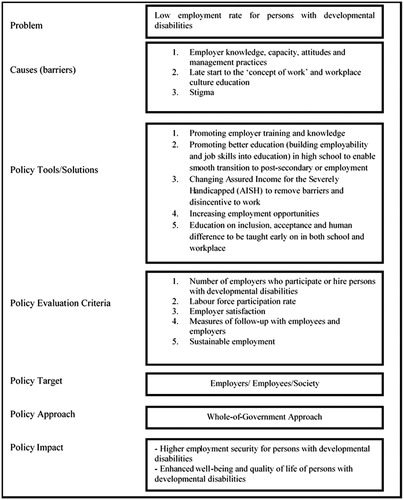

Implementation of the wide range of prioritized solutions falls under the responsibility of various sectors, including government agencies, civil society, non-profit organizations, academic institutions, and the private sector. A strategy to improve policy implementation requires inter-agency and cross-sectoral collaboration if barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities are to be adequately addressed. Our findings suggest that policy and decision makers need to address barriers more holistically by targeting policies not only at persons with developmental disabilities (such as skill development or training) but also at employers and society broadly. The multi-causal nature of barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities – termed a “wicked problem” [Citation84] – demands a “Whole of Government” or “Whole of Society” approach. The Whole of Government approach () refers to initiatives that enable various agencies across a wide range of sectors (e.g., government, private sector, civil society, etc.) to work together to address “wicked” problems that cut across ministries or departments. The Whole of Government’ approach aims to improve collaboration, coordination, and integration in policy and implementation [Citation85].

Figure 2. Policy mind map to address barriers to labor force participation for persons with a developmental disability.

The multi-causal nature of the barriers prioritized by diverse stakeholders in our research lends support to the idea of “systemic framing” of this “wicked” problem (i.e., employment for persons with developmental disabilities). Framing a problem, or how people discuss the central ideas surrounding it, has a strong impact on how the problem is understood, who is responsible for it, and what should be done to address it [Citation86]. Theory of social construction of policy problems posits that the way a problem is framed and constructed informs subsequent policy solutions [Citation85,Citation86]. In a similar vein, theories of agenda setting [e.g., Citation88,Citation89] place an emphasis on how a problem is defined and framed as a public problem and its implications for future policy outcomes. Gusfield (1984) argues that frames generally refer to causal links, ownership, responsibility, and policy solutions [Citation87]. We believe the “systemic framing” of barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities leads to the identification of a wide range of policy solutions that fall under the responsibility of diverse sectors for implementation.

Evaluation is key for implementation. Prioritized criteria to evaluate policies were broad and need to be applicable to all policy solutions identified (). The five core elements that participants viewed as being imperative in any policy evaluation with regards to employment for persons with developmental disabilities include measures of: employer participation; labour force participation; employer satisfaction; follow-up with employees and employers; and sustainable employment. These criteria are useful in determining the relevance and effectiveness of a particular policy (). For a policy measure to be capable of improving employment security and enhancing the well-being and quality of life of persons with developmental disabilities, it should have the potential to satisfy one or more of the criteria identified and prioritized in our research. The literature provides little information on evaluation criteria and is an area for future research.

Viewing the identified policy solutions through the lens of existing supports, we see that there are currently many organizations, services, and programs across Canada that are working to improve employment outcomes for persons with developmental disabilities (which similarly is viewed to be the case in some other world regions). There are programs and policies at both the federal and provincial levels that provide education, training, counselling, job assistance services, skills development, and targeted wage subsidies for persons with developmental disabilities in advancing their position in the labour market – whether they are employed or not ().

Table 3. Employment supports available for Persons with developmental disabilities.

In addition, there are employer-focused opportunities in Canada such as the Canada Job Fund or the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities. These programs suggest an attempt of government to shift from a predominant focus on employees/individuals with developmental disabilities to considerations for an inclusive workplace. The 2017 federal budget indicated that the Government of Canada will be exploring options to improve employment outcomes and promote equality of opportunity. They have also pledged to return to cooperative federal-provincial/territorial development of skills and training programs through new Workforce Development Agreements and the abandonment of the Canada Job Fund. Once in place, these changes will shift focus from employer subsidies that upgrade skills of currently employed workers to the provision of supports to allow persons with disabilities to enter and stay in the labour market. This is particularly important to persons with developmental disabilities as the majority of working-age adults are not in the labour force and are not benefitting from the structure of the previous Canada Job Fund [Citation7,Citation65].

In Canada, there is legislation in place provincially and federally to protect persons with developmental disabilities from discrimination (e.g., Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canadian Human Rights Act, Alberta Bill of Rights, Alberta Human Rights Act, etc.). Despite this legislation, participants in this study identified potential discrimination against persons with developmental disabilities as the result of employer-based stigma, especially if an employer has past negative experience in employing a person with developmental disabilities. The same has been reported elsewhere where stigma and negative assumptions about persons with disabilities were seen as key barriers to implementation of rights-based policies such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Citation90]. The fact that stigma was one of the top three barriers to participation or sustaining participation in the labour market for persons with developmental disabilities suggests that despite significant constitutional and institutional support and protection, persons with developmental disabilities continue to face extensive and deleterious discrimination.

A strength of our study is its recognition that change will only occur if we address employment for persons with developmental disabilities on multiple fronts, working toward a unified and consistent strategy and message. It is crucial that our findings (and namely the overlap in them) be considered for effective holistic policy responses to the current poor level of labour force participation for persons with developmental disabilities. As the top five policy solutions span employers (employer knowledge, capacity, attitudes, and management practices), persons with developmental disabilities and their families/caregivers (late start to the “concept of work” and workplace culture education) and society overall (stigma) (), findings indicate that policy solutions should not be implemented in a vacuum or treated as independent from one another. While a patchwork of disjointed policies, programs and supports exists, without a Whole of Government approach and the interagency and cross-sectoral collaboration necessary to address both external and internal barriers, little progress in changing the status quo is expected.

Study limitations

The participation of persons with developmental disabilities was a limitation of this study. Lower than anticipated participation of persons with developmental disabilities was due to the sampling method (convenience), exclusion criteria that excluded those who were unable to provide full informed consent, and last-minute cancellations. To overcome this limitation, we included parents/family caregivers as a proxy for persons with developmental disabilities and held a focus group after the event just with persons with developmental disabilities to better understand their perspective on the prioritized barriers and solutions.

The use of four different table facilitators in the table groups is a second limitation. To minimize inter-group variation, the lead facilitator, an experienced professional facilitator, had provided training to table facilitators prior to the event. There was also a detailed NGT protocol prepared and distributed by the lead facilitator and practiced by table facilitators prior to the event on two separate preparation sessions.

A further potential limitation is that research participants may not have had (or felt that they had) an equal voice in discussion relative to one another, and perhaps all voices were not equally “heard.” This indeed is a key challenge in group settings in that some voices may be inequitably amplified or muted in conversation [Citation62]. Our strategy to minimize this challenge was to employ the NGT and with a highly experienced professional facilitator who made every attempt to encourage all participants to contribute to discussions. Both the lead and table facilitators played a crucial role in facilitating purposeful interactions between group members and helping participants to feel at ease and equal. Our two online surveys (steps two and three of the modified Delphi) also provided participants with equitable opportunity to anonymously choose potential policy solutions and criteria. Although every attempt to minimize this limitation was made, some participants may not have contributed as much as they would have wanted.

Conclusions

This study sought to develop consensus among diverse stakeholders on barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities, potential solutions to address these barriers, and criteria to evaluate identified policy solutions. Barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities are multi-factorial. Identified policy solutions to address these barriers are wide-ranging and fall under the responsibility of multiple sectors for implementation. This calls for cross-sectoral collaboration using a Whole of Government’ approach. How to employ such a Whole of Government’ approach and develop cross-sectoral collaborations among a wide range of stakeholders with different ideas/values, interests, and institutions, remains an important area of future innovation and research.

Given the predominantly quantitative focus of much of the studies on this topic to date and that quantitative data is generally more descriptive than explanatory, initiating more qualitative research to assess the barriers to employment for persons with developmental disabilities and potential policy solutions is important. Here, we specifically recommend the use of in-depth interviews or other exploratory/explanatory approaches with a wide range of stakeholders to obtain a deeper understanding of the key barriers and policy solutions. It is anticipated that this will move beyond only prioritizing barriers and solutions, which also allows comparing views across diverse stakeholders.

Ethical Issues

The study was approved by the Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary.

Supplementary_Material.pdf

Download PDF (84.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Lisa Petermann, the lead facilitator of our event, and Dr. Myles Leslie, Stephanie Dunn, Ramesh Lamsel, Shainur Premji, and Theresa Jubenville who facilitated our table groups. We thank all stakeholders who willingly participated in our study and contributed their knowledge and expertise. We also thank the event team at the School of Public Policy for their contribution to organizing our event.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104.

- Curnock E, Leyland AH, Popham F. The impact on health of employment and welfare transitions for those receiving out-of-work disability benefits in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2016;162:1–10.

- Emerson E, Madden R, Graham H, et al. The health of disabled people and the social determinants of health. Public health. 2011;125:145–147.

- Jahoda A, Kemp J, Riddell S, et al. Feelings about work: a review of the socio-emotional impact of Supported Employment on people with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2008;21:1–18.

- Austin RD, Pisano GP. Neurodiversity as a competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review. 2017;95:96–103.

- Baumberg B, Jones M, Wass V. Disability prevalence and disability-related employment gaps in the UK 1998–2012: different trends in different surveys? Soc Sci Med. 2015;141:72–81.

- Prince MJ. Inclusive employment for Canadians with disabilities: toward a new policy framework and agenda. IRPP Study. 2016:60.

- McColl MA, Schaub M, Sampson L, et al. A Canadians with disabilities act? Canadian Disability Policy Alliance. 2010.

- Zwicker J, Zaresani A, Emery JH. Describing heterogeneity of unmet needs among adults with a developmental disability: an examination of the 2012 Canadian Survey on Disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;65:1–11.

- Till M, Leonard T, Yeung S, et al. A profile of the labour market experiences of adults with disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years and older, 2012. Statistics Canada. 2015.

- Turcotte M. Persons with disabilities and employment. Women. 2014;49:54.5.

- Ellenkamp JJ, Brouwers EP, Embregts PJ, et al. Work environment-related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J occup Rehabil. 2016;26:56–69.

- Schur L, Han K, Kim A, et al. Disability at work: a look back and forward. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:1–16.

- Swanson JL, Woitke MB. Theory into practice in career assessment for women: assessment and interventions regarding perceived career barriers. J Career Assessment. 1997;5:443–462.

- Hagner D, Cooney BF. “I do that for everybody”: supervising employees with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2005;20:91–97.

- Scheef AR. Exploring barriers and strategies for facilitating work experience opportunities for individuals with intellectual disabilities enrolled in post-secondary education programs. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Washington State University; 2016.

- Dudley C, Nicholas DB, Zwicker J. What do we know about improving employment outcomes for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder? SPP Research Paper. 2015:8.

- Hendricks D. Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorders: challenges and strategies for success. J Vocat Rehabil. 2010;32:125–134.

- Chiang HM, Cheung YK, Li H, et al. Factors associated with participation in employment for high school leavers with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:1832–1842.

- Su CY, Lin YH, Wu YY, et al. The role of cognition and adaptive behavior in employment of people with mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil. 2008;29:83–95.

- Hurlbutt K, Chalmers L. Employment and adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2004;19:215–222.

- Holwerda A, van der Klink JJ, de Boer MR, et al. Predictors of work participation of young adults with mild intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:1982–1990.

- Erickson WA, von Schrader S, Bruyère SM, et al. The employment environment: employer perspectives, policies, and practices regarding the employment of persons with disabilities. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2014;57:195–208.

- Kocman A, Fischer L, Weber G. The Employers’ perspective on barriers and facilitators to employment of people with intellectual disability: a differential mixed-method approach. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2017;31:120-131.

- Hernandez B, Keys C, Balcazar F. Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities and their ADA employment rights: a literature review. J Rehabil. 2000;66:4.

- Ju S, Zhang D, Pacha J. Employability skills valued by employers as important for entry-level employees with and without disabilities. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2012;35:29–38.

- Morgan RL, Alexander M. The employer's perception: employment of individuals with developmental disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2005;23:39–49.

- Burke J, Bezyak J, Fraser RT, et al. Employers' attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: a review of the literature. Aus J Rehabil Couns. 2013;19:21–38.

- Kaye HS, Jans LH, Jones EC. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:526–536.

- Houtenville A, Kalargyrou V. People with disabilities: employers’ perspectives on recruitment practices, strategies, and challenges in leisure and hospitality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2012;53:40–52.

- Carter EW, Austin D, Trainor AA. Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2012;23:50–63.

- Gormley ME. Workplace stigma toward employees with intellectual disability: a descriptive study1. J Vocat Rehabil. 2015;43:249–258.

- While AE, Clark LL. Overcoming ignorance and stigma relating to intellectual disability in healthcare: a potential solution. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:166–172.

- Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health. 1972;62:337–342.

- Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi method: techniques and applications. Vol. 29. Reading (MA): Addison-Wesley; 1975.

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:566–574.

- Joshi GS, Bouck EC, Maeda Y. Exploring employment preparation and postschool outcomes for students with mild intellectual disability. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2012;35:97–107.

- Moore EJ, Schelling A. Postsecondary inclusion for individuals with an intellectual disability and its effects on employment. J Intellect Disabil. 2015;19:130–148.

- Antioch KM, Drummond MF, Niessen LW, et al. International lessons in new methods for grading and integrating cost effectiveness evidence into clinical practice guidelines. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2017;15:1.

- Chan W, Smith LE, Hong J, et al. Factors associated with sustained community employment among adults with autism and co-occurring intellectual disability. Autism. 2017;22:294–303.

- Bush KL, Tassé MJ. Employment and choice-making for adults with intellectual disability, autism, and down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;65:23–34.

- Petner-Arrey J, Howell-Moneta A, Lysaght R. Facilitating employment opportunities for adults with intellectual and developmental disability through parents and social networks. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:789–795.

- Meltzer A, Bates S, Robinson S, et al. What do people with intellectual disability think about their jobs and the support they receive at work? A comparative study of three employment support models. UNSW Australia Social Policy Research Center. 2016.

- Zappella E. Employers’ attitudes on hiring workers with intellectual disabilities in small and medium enterprises: an Italian research. J Intellect Disabil. 2015;19:381–392.

- Antaki C, Young N, Finlay M. Shaping clients' answers: departures from neutrality in care-staff interviews with people with a learning disability. Disabil Soc. 2002;17:435–455.

- Cambridge P, Forrester-Jones R. Using individualised communication for interviewing people with intellectual disability: a case study of user-centred research. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2003;28:5–23.

- Tuffrey‐Wijne I, Butler G. Co-researching with people with learning disabilities: an experience of involvement in qualitative data analysis. Health Expect. 2010;13:174–184.

- Beadle-Brown J, Ryan S, Windle K, et al. Engagement of people with long term conditions in health and social care research: barriers and facilitators to capturing the views of seldom-heard populations. Canterbury: Quality and Outcomes of Person-Centred Care Policy Research Unit, University of Kent. 2012.

- Williamson HJ, Perkins EA, Massey OT, et al. Family caregivers as needed partners: recognizing their role in medicaid managed long-term services and supports. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2018;15:214–225.

- McMillan SS, Kelly F, Sav A, et al. Using the Nominal Group Technique: how to analyse across multiple groups. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2014;14:92–108.

- Spencer DM. Facilitating public participation in tourism planning on American Indian reservations: a case study involving the Nominal Group Technique. Tourism Management. 2010;31:684–690.

- Harvey N, Holmes CA. Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract. 2012;18:188–194.

- Tuffrey-Wijne I, Wicki M, Heslop P, et al. Developing research priorities for palliative care of people with intellectual disabilities in Europe: a consultation process using nominal group technique. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:36.

- Allen J, Dyas J, Jones M. Building consensus in health care: a guide to using the nominal group technique. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9:110–114.

- Silverman D. Qualitative research. 4E ed. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2016.

- Ghisoni M, Wilson CA, Morgan K, et al. Priority setting in research: user led mental health research. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3:4.

- Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information Management. 2004;42:15–29.

- Marques AI, Santos L, Soares P, et al. A proposed adaptation of the European Foundation for Quality Management Excellence Model to physical activity programmes for the elderly-development of a quality self-assessment tool using a modified Delphi process. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:104.

- Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41:376–382.

- Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:979–983.

- Carey MA, Asbury JE. Focus group research. New York: Routledge; 2016.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Singapore: SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Powell RA, Single HM. Focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8:499–504.

- Silverman D. Doing qualitative research: a practical handbook. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Torjman S. Dismantling the Welfare Wall for Persons with Disabilities. Caledon Institute of Social Policy; 2017.

- Dudley C, Nicholas DB, Zwicker JD. What do we know about improving employment outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder? The School of Public Policy Publications. 2015;8.

- Nicholas DB, Attridge M, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Vocational support approaches in autism spectrum disorder: a synthesis review of the literature. Autism. 2015;19:235–245.

- Nicholas D, Roberts W, Macintosh C. Advancing vocational opportunities for adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Proceedings from the 1st annual Canadian ASD Vocational Conference. Currents: Scholarship in Human Services. 2014;13:1–19.

- Nicholas DB, Mitchell W, Dudley C, et al. An ecosystem approach to employment and Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:264–275.

- Nicholas DB, Zwaigenbaum L, Zwicker J, et al.Evaluation of employment-support services for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;22:693-702.

- McLaren J, Lichtenstein JD, Lynch D, et al. Individual placement and support for people with autism spectrum disorders: a pilot program. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2017;44:365–373.

- Seaman RL, Cannella-Malone HI. Vocational skills interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorder: a review of the literature. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2016;28:479–494.

- Hillier A, Campbell H, Mastriani K, et al. Two-year evaluation of a vocational support program for adults on the autism spectrum. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2007;30:35–47.

- Howlin P, Alcock J, Burkin C. An 8 year follow-up of a specialist supported employment service for high-ability adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2005;9:533–549.

- Robertson JM, Emerson E. A systematic review of the comparative benefits and costs of models of providing residential and vocational supports to adults with autism spectrum disorder: report for the National Autistic Society. 2006.

- Taylor JL, McPheeters ML, Sathe NA, et al. A systematic review of vocational interventions for young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130:531–538.

- Walsh L, Lydon S, Healy O. Employment and vocational skills among individuals with autism spectrum disorder: predictors, impact, and interventions. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;1:266–275.

- Hendricks DR, Wehman P. Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorders: review and recommendations. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2009;24:77–88.

- Shattuck PT, Narendorf SC, Cooper B, et al.Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1042–1049.

- Westbrook JD, Fong CJ, Nye C, et al. Transition services for youth with autism: a systematic review. Res Soc Work Pract. 2015;25:10–20.

- Kohler PD. Best practices in transition: substantiated or implied? Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 1993;16:107–121.

- Landmark LJ, Ju S, Zhang D. Substantiated best practices in transition: fifteen plus years later. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2010;33:165–176.

- Test DW, Mazzotti VL, Mustian AL, et al. Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2009;32:160–181.

- Rittel HW, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973;4:155–169.

- Christensen T, Lise Fimreite A, Laegreid P. Reform of the employment and welfare administrations—the challenges of co-coordinating diverse public organizations. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2007;73:389–408.

- Stone DA. Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Polit Sci Q. 1989:281–300.

- Gusfield JR. The culture of public problems: drinking-driving and the symbolic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984.

- Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Agendas and instability in American politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010.

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. New York: Longman; 1995.

- Hussey M, MacLachlan M, Mji G. Barriers to the implementation of the health and rehabilitation articles of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities in South Africa. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6:207.