Abstract

Purpose: This study evaluated the long-term effects of Brainz, a community-based treatment programme for adults with acquired brain injury in the chronic phase of the injury.

Materials and methods: The treatment consisted of group modules and biweekly individual home training sessions. Of the 62 subjects who participated in the original effect study, 30 subjects were available for follow-up assessment. Selection bias analysis of baseline characteristics revealed no significant differences between the included and the excluded group. Baseline measurements were compared with follow-up measurements to assess effect consolidation after treatment cessation.

Results: The increased level of patient satisfaction with social participation found one year after baseline, was maintained at follow-up. The positive effects on the number of perceived difficulties in daily life and need of care that were found one year after baseline measurements were no longer present. However, an additional improvement in self-reported overall health was observed. The decreased level of self-esteem measured one year after baseline, was no longer present at follow-up.

Conclusions: Overall, this study suggests consolidation of the effects of this community-based treatment programme. Further enhancement of treatment effects could be established by the implementation of booster sessions or peer support groups. Future controlled studies are needed.

Acquired brain injury can lead to consequences in a variety of life domains that can persist after patients return to their homes.

A low-intensity community-based rehabilitation programme called Brainz demonstrated to improve patient satisfaction with societal participation and reduce perceived difficulties in daily life and need of care.

This study suggests the consolidation of these effects.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is an important health condition, encompassing all injuries to the brain that have been acquired after birth, such as stroke and traumatic brain injury. ABI can lead to consequences in a variety of life domains that can persist when patients return home after being discharged from the hospital or rehabilitation centre, potentially resulting in problems when patients attempt to resume their everyday lives [Citation1,Citation2]. The presence of these persisting consequences in the longer term highlights the need for a rehabilitation programme that addresses all important life domains so as to improve everyday functioning with ABI. Several comprehensive rehabilitation programmes exist that focus on the many different aspects of functioning after ABI [Citation3]. However, such programmes might be too intensive for patients who are able to live at home and function independently, yet who experience problems in everyday functioning and participation [Citation4]. Low-intensity integrated outpatient rehabilitation programmes, by contrast, can be effective in the attainment of individual patient goals, but these effects do not always generalise to the level of societal participation and general quality of life [Citation4]. An explanation for the lack of generalisation of effects could be that the focus is on specific goals and that the generalisation during learning is not explicitly addressed [Citation5].

In order to assist patients with applying the skills that they acquired in treatment to their everyday life situations, a community-based treatment programme called Brainz, was developed for people with ABI. This programme is offered in the chronic phase and consists of group sessions at care institutions as well as individual training sessions at the patients’ home. In a recent pilot study, Brainz demonstrated to significantly improve satisfaction of patients with societal participation, and reduce perceived difficulties in daily life and need of care one year after the start of the programme [Citation6]. However, patients also reported a lower level of self-esteem after treatment termination, which could be attributed to gaining more insight into their own functioning after having participated.

A limitation of the pilot study was the lack of a follow-up measurement to investigate the duration of the treatment effects. Consequently, the current one-year follow-up study was performed to assess to what extent the treatment effects of Brainz consolidated after cessation of the programme. Since Brainz aims to let patients acquire generalizable strategies rather than specific skills, we expected the treatment effects to have lasted into follow-up.

Materials and methods

Intervention

Brainz is a community-based treatment programme for people with ABI in the chronic phase who experience cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioural problems that interfere with their daily functioning. The programme features group sessions in a clinical setting combined with individual treatment at the patients’ home, promoting generalisation of treatment effects. Brainz consists of cognitive, psychomotor, and physical training that is aimed at rebuilding ABI patients’ perspectives in life by teaching them how to set and achieve goals. As such, the intention is not to treat impairments, but rather to teach patients how to manage, compensate for, and accept the consequences of ABI in order to augment independent functioning and societal participation.

During the programme, participants attend at least two out of five group modules (“dealing with change,” “getting a grip on your energy,” “thinking and doing,” “getting active A,” and “getting active B”). The three cognitive modules, each consisting of 14 weekly two-hour sessions, are conducted by cognitive trainers. Physical modules consist of 28 two-hour sessions offered twice a week and are carried out by a psychomotor therapist or physiotherapist. The individual home training sessions are delivered by a home practitioner and are aimed at supporting the family system and helping the patient apply the acquired skills and knowledge to daily life situations. Home sessions last until the end of the programme. As Brainz is adapted to the patients’ individual needs, its duration varies from 28 weeks (two group modules and home training) to 42 weeks (five group modules and home training). For more information on the intervention, please consult Middag et al. [Citation6].

Participants

All patients who were included in the primary Brainz study between September 2014 and January 2015 and who could be contacted were approached for follow-up measurements. Participants did not receive any reimbursement. Inclusion criteria of the primary study were being over 18 years old, having ABI and experiencing cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioural problems that interfered with daily functioning, living at home without receiving medical or rehabilitation treatment related to their ABI, and having sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. Furthermore, participants had to be referred to one of the six participating Dutch healthcare organisations offering support and treatment to persons with ABI (Heliomare, InteraktContour, De Noorderbrug, Middin, Stichting Gehandicaptenzorg Limburg and Samenwerkende Woon- & Zorgvoorzieningen). Exclusion criteria were suffering from progressive neurodegenerative diseases, severe aphasia, substantial memory deficits, predominant psychiatric disorders (e.g., serious depression), predominant addiction or substance abuse or other problems in the personal life that might impede the course of the treatment (e.g., financial problems). Follow-up measurements were performed between June and November 2016.

Design

The current study is a follow-up measurement of a prospective multicentre cohort study. Patient one-year follow-up measurements were compared with baseline measurements.

Outcome measures

Demographic (sex, age, educational level, employment status, type of household) and injury-related characteristics (time since injury, age at injury, cause of injury, cognitive functioning) were collected at baseline. Cognitive functioning was screened for using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [Citation7], with scores ranging from 0-30. Total scores lower than 26 indicate cognitive impairment.

Objective and subjective societal participation was measured using the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation – Participation (USER-P) [Citation8]. The USER-P comprises four subscales. The subscale “Frequency A” reflects participation in vocational activities, whereas “Frequency B” comprises leisure and social activities. The third subscale “Restrictions” measures the level of experienced participation restrictions. The fourth subscale “Satisfaction” comprises satisfaction with the level of participation. Total scores per scale are transformed linearly into a 0-100 scale, with higher scores indicating a higher level of participation on all scales (higher frequency, less restrictions, higher satisfaction).

In order to assess needs of care, the Need of Care questionnaire was developed in the preliminary study, due to the fact that similar, conventional instruments are too extensive for use in the current study. The Need of Care questionnaire assesses experienced difficulties in daily life and need of care in 10 life domains. Item scores are summed, leading to two total scores (0-10), with higher scores indicating worse outcome.

The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) was used to assess global self-esteem [Citation9]. Scores are summed with higher total scores indicating a higher level of global self-esteem.

As a secondary outcome measure, functional outcome was assessed by means of the COOP/WONCA [Citation10]. Higher scores indicate a higher level of perceived difficulties.

Procedure

Patients were approached to participate in follow-up measurements by the clinicians or the research assistants of the participating organisations via telephone or at a regular patient contact. The USER-P, RSES, COOP/WONCA and the Need of Care questionnaire were administered by the clinicians or sent by mail, according to the patient’s preference. In some cases, clinicians read out the questions on the questionnaire. All participants were instructed to report their own opinion.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics. Differences between baseline characteristics of included patients and drop-outs were assessed to check for potential selection bias. Depending on the distribution, independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were employed. In the case of categorical data, Pearson chi-square tests (multiple categories) or Fischer’s exact tests (dichotomous variables) were used.

We assessed long-term effectiveness of the programme using paired samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests to compare differences between baseline (T0) and follow-up measurements (T2). A significance level (Alpha) of 0.01 was used to correct for multiple testing. All analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software, version 24 [Citation11].

Ethical Considerations

Official approval was requested but deemed unnecessary by the Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Centre as all measurements were conducted as part of routine clinical practice, see Middag-van Spanje et al. [Citation6]. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the effect study. Only those who could be reached for follow-up measurement and who gave oral consent to participate in follow-up measurements were included in the current study. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Participants

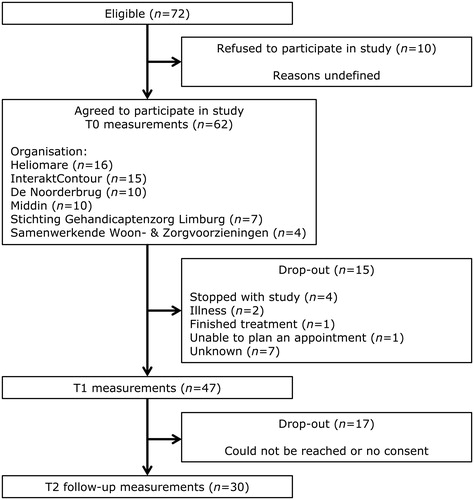

Demographic characteristics of patients are displayed in . Out of the 62 patients who participated in the previous study on the effect of Brainz, 30 (48%) agreed to participate in the follow-up study (). The mean age at admission of the subjects (67% males) was 52 years (sd = 12) and the mean time between T1 and T2 measurements was 11 months. The majority (63%) of the participants had a lower education level. The patients had sustained a stroke (n = 17, 23%), traumatic brain injury (n = 7, 57%), or a brain tumour (n = 3, 10%). Three patients (10%) suffered multiple brain injuries. The mean time since injury at follow-up was 7 years (sd = 5) and the mean age at which patients suffered their first injury was 47 (sd = 14). Patients who participated in the follow-up study did not differ from the excluded group in terms of patient- or injury characteristics ( and ).

Figure 1. Flow chart of participants through the original effect study (T0 and T1) and the current follow-up study (T2). T0: baseline; T1: one year after the start of the programme; T2: follow-up measurement.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of people with ABI.

Table 2. Medically relevant characteristics of people with ABI.

Outcomes

displays the outcomes on the primary (USER-P, Need of Care and RSES) and secondary (COOP/WONCA) measures that were administered at baseline, one year after baseline and follow-up. For comparison purposes, means and standard deviations were displayed for measurements of the current subgroup that were taken one year after the start of the programme (T1) (please note that these scores can differ from total group scores that were reported in the preliminary study).

Table 3. Mean scores on outcome measures at baseline (T0), one year after the start of the programme (T1) and at follow-up (T2).

Concerning participation, there was a significant increase in patient satisfaction with level of participation between baseline and follow-up measurement (p = .009). Frequency of participation and participation restrictions did not differ at follow-up when compared to baseline values. There was no significant effect on self-esteem, perceived difficulties in life and the number of these difficulties that patients were in need of care for at follow-up measurement. With respect to functional status, people with ABI showed a significant reduction of self-reported problems with overall health (p = .007) at follow-up compared to baseline.

Discussion

The current study examined the long-term effects of a community-based treatment programme for people with ABI. We found the programme to have established a long-term increase in the level of patient satisfaction with their level of social participation and an increased self-reported overall health.

Comparison with the effect study

A comparison can be made with the results of the original effect study (Middag-van Spanje et al. [Citation6]), which looked into the effects of the Brainz intervention on personal outcomes (such as physical fitness when one of the physical modules was selected and caregiver burden for patients who received informal care) as well as general outcomes (such as participation and need of care). In the current follow-up study, only the general primary outcome measures and one of the secondary outcome measures on general health (COOP/WONCA) were administered to assess long-term effects.

Originally, the Brainz programme significantly improved the satisfaction with social participation. This effect consolidated after cessation of the programme. No differences were found for other aspects of participation, similar to the results of the effect study. Furthermore, Brainz initially significantly decreased the number of perceived difficulties in daily life as well as the number of difficulties for which persons with ABI needed care. Neither of these effects were found in the follow-up measurements, although, data showed a decrease of difficulties for which persons needed care. Furthermore, it should be noted that the original sample showed a substantially higher mean number of problems for which the patients were in need of care at baseline (baseline M = 3.7) than the follow-up sample did (baseline M = 2.7). With regard to functional status, overall health as experienced by participants improved significantly, an effect that was not present in measurements that were taken one year after baseline, as part of the effect study. Moreover, self-esteem of participants showed a significant decrease after programme cessation, which was no longer the case at follow-up measurement.

The paper on the effect study of Brainz [Citation6] proposed several explanations for the increase in satisfaction of participants with their level of societal participation regardless of change(s) in the frequency of participation and experienced participation restrictions. First, it was hypothesised that patient satisfaction with level of participation was enhanced because of the number of activities that were performed as a part of participating in Brainz, without altering the frequency of activities or the level of perceived participation restrictions outside the programme. However, since the effect on participation satisfaction persisted after Brainz had finished, it is unlikely caused by participating in the programme itself. Another possibility is that patients did engage more (and were therefore less restricted) in vocational activities at the expense of leisure activities, as previous research indicated that patients with ABI experience greater difficulty in resuming vocational activities than they do social activities [Citation1]. Since the current study differentiated for vocational activities (USER-P – Frequency A) and leisure activities (USER-P – Frequency B), but still found no effect on Frequency A (vocational activities), this was likely not the case. The results might also be explained by the possibility of patients becoming better adjusted to their disabilities. The results of the current study confirm this hypothesis, as participants do experience problems in daily life, but report a decreased need of care for these problems.

The no-longer significant decrease of self-esteem might be explained by a potential power problem. However, it could also be explained in light of the programme. Potentially, participants were confronted with their own disabilities during the programme, leading to a decreased self-esteem, as previous research indicated higher levels of cognitive functioning and awareness of deficit are associated with lower self-esteem [Citation12]. At the time of follow-up measurement, their confidence might have been rebuilt by applying newly learned strategies in everyday life and becoming better adjusted to their disabilities.

Lastly, the long-term improvement on overall health could be explained by differences in subsamples, as the current sample showed lower levels of overall health (baseline M = 3.3) than the total sample (baseline M = 2.8), suggesting that the follow-up sample had more room for improvement.

Strengths and weaknesses

A strength of this study is the fact that it comprises a long-term follow up measurement. In light of the cost-effectiveness of intervention programmes, evaluating the consolidation of effects in any healthcare intervention is a crucial part of process-evaluation [Citation13]. In performing the current study, we have demonstrated the long-term effectiveness, and therefore sustainability, of the Brainz programme.

This follow-up study had certain limitations. Due to the lack of a control group, we cannot provide a decisive answer to the question whether the changes can be fully attributed to the programme. However, the mean time since injury was long and spontaneous recovery is not to be expected any more. Similarly, as ABI patients in The Netherlands regularly do not receive care at home in the chronic phase after acquiring the injury, the effects of the programme could merely be an effect of personal attention and therapeutic rapport, rather than the intervention itself. Although this issue can only be addressed by further research, it can be argued that the intervention had effects beyond those of personal attention, as treatment effects remained after the cessation of home visits. Further, only 50% of the original sample could be reached and agreed to follow-up measurements. However, selection bias analysis revealed no significant differences between the included and excluded group. Overall, original sample sizes and loss to follow up led to a small study sample, reducing the statistical power of this study and the ability to apply more advanced statistical methods.

Future directions

Future research should aim at evaluating the Brainz programme in a larger sample by means of a randomised controlled trial. Additionally, therapists could consider the possibility of adding booster sessions to the intervention in order to ensure the acquired skills are maintained over time or to assist in reacting to newly encountered problematic situations or circumstances, as such sessions have been proven to be effective in consolidating treatment effects in other intervention studies [Citation14].

To further reinforce the effects, participants could organise peer support meetings. Previous research has indicated that peer support can be beneficial for both patients and their caregivers [Citation15,Citation16] without impinging on healthcare budgets, suggesting that such meetings might provide a more cost-effective alternative to booster sessions. Accordingly, group trainers could encourage participants to form peer support groups after finishing their modules.

Conclusion

This study indicated that the effect of a community-based treatment programme for people with ABI on participation satisfaction and need of care was consolidated after treatment cessation. An additional improvement in self-reported overall health was measured at follow-up. The reduction in self-esteem that was measured after treatment cessation was no longer present. Healthcare professionals could consolidate and potentially further enhance treatment effects by means of booster sessions or peer support meetings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants, the participating clinicians and the research assistants who conducted the measurements and the Brainz research group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blömer AMV, Van Mierlo ML, Visser-Meily JM, et al. Does the frequency of participation change after stroke and is this change associated with the subjective experience of participation? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(3):456–463.

- Ponsford JL, Downing MG, Olver J, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of patients with traumatic brain injury: outcome at two, five, and ten years post-injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(1):64–77.

- Geurtsen GJ, van Heugten CM, Martina JD, et al. Comprehensive rehabilitation programmes in the chronic phase after severe brain injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(2):97–110.

- Rasquin SM, Bouwens SF, Dijcks B, et al. Effectiveness of a low intensity outpatient cognitive rehabilitation programme for patients in the chronic phase after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20(5):760–777.

- Babulal GM, Foster ER, Wolf TJ. Facilitating transfer of skills and strategies in occupational therapy practice: practical application of transfer principles. Asian J Occup Ther. 2016;11(1):19–25.

- Middag-van Spanje M, Smeets S, van Haastregt J, et al. Outcomes of a community-based treatment programme for people with acquired brain injury in the chronic phase: a pilot study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;29(2):305–321.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699.

- Post MW, van der Zee CH, Hennink J, et al. Validity of the utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(6):478–485.

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979.

- Weel C, König-Zahn C, Touw-Otten F. Measuring functional status with the COOP/WONCA charts: a manual. Groningen (the Netherlands): Noordelijke Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken (NCG)/Northern Centre of Health Care Research (NCH); 2012.

- IBM Corporations. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macbook (Version 24.0). Armonk (NY): IBM Corporations; 2016.

- Cooper-Evans S, Alderman N, Knight C, et al. Self-esteem as a predictor of psychological distress after severe acquired brain injury: an exploratory study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18:607–626.

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

- Fleig L, Pomp S, Schwarzer R, et al. Promoting exercise maintenance: how interventions with booster sessions improve long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58(4):323–333.

- Hibbard MR, Cantor J, Charatz H, et al. Peer support in the community: initial findings of a mentoring program for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their families. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002;17(2):112–131.

- Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Wertheimer J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of peer mentoring for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their significant others. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(8):1297–1304.