Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the feasibility of Family Group Conference for promoting return to work by clients receiving work disability benefits from the Social Security Institute in the Netherlands.

Methods: We conducted a mixed-method pre- post-intervention feasibility study, using questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and return to work plans drafted in Family Group Conferences. A convenient sample of Labour experts, Clients, and Facilitators was followed for a period of six months. Feasibility outcomes were demand, acceptability, implementation and limited efficacy of perceived mental health and level of participation.

Results: Fourteen labour experts and sixteen facilitators enrolled in the study. Of 28 eligible clients, nine (32%) participated in a Family Group Conference. About 78% of the Family Group Conferences were implemented as planned. Participant satisfaction about Family Group Conference was good (mean score 7). Perceived mental health and level of participation improved slightly during follow-up. Most actions in the return to work plans were work related. Most frequently chosen to take action was the participating client himself, supported by significant others in his or her social network. Six months after the Family Group Conference five participating clients returned to paid or voluntary work.

Conclusions: Family Group Conference seems a feasible intervention to promote return to work by clients on work disability benefit. Involvement of the social network may have added value to support the clients in this process. An effectiveness study to further develop and test Family Group Conferences is recommended.

Family Group Conference may represent a promising approach to be used in activation strategies to enhance social inclusion and return to work of persons receiving disability benefits.

Conventional supply-oriented activation services could be improved by providing the Family Group Conference to unemployed persons on disability benefit.

Involvement of the social network may have added value for return to work of clients receiving work disability benefits.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

In many western welfare states, activation programs have been introduced to enhance social inclusion and return to work of persons receiving work disability benefits [Citation1,Citation2]. However, effectiveness of such activation programs is limited and labour force participation among people with disabilities remains low [Citation3].

Long-term unemployment and work disability is an important social determinant of health inequalities across European Countries [Citation4]. Unemployed individuals often report worse health status, experience more depressive symptoms, and are at a higher risk of mortality [Citation5]. Re-employment improves mental and physical health, and generally increases quality of life [Citation6].

In 2011 The World Health Organization recommended a person-centred and community based service aimed at return to work, relying on client empowerment and encouraging unemployed people with disabilities to take their own responsibility to find work. Such an approach would more likely involve the unemployed in decisions about the support they receive and therefore give them more control over their lives [Citation7]. Until recently, unemployed persons receiving work disability benefit have often obtained only fragmented provision of social assistance and employment services by social security administration, municipalities and health services. Moreover, most programs have still been supply-oriented, offering off-the-shelf service, instead of being person-centred,meeting clients’ needs and desires [Citation8].

Previous studies have pointed to the importance of the role of family and friends in supporting people with chronic diseases in their return to work process [Citation9–11]. Such social support increases, for example, the likelihood that breast cancer survivors [Citation12] and patients with chronic low back pain will return to work [Citation13]. Studies have also reported that social support enhances the participation rate of unemployed people and gives them a stronger position in the labour market [Citation14,Citation15]. According to Furlong and Cartmel [Citation16] the presence of social and cultural capital, e.g., education, skills, supportive family and effective social networks, gives starters at the labour market strong advantages. Their study shows family and social networks to be important sources of support, able to inspire better patterns of recruitment. In a qualitative British study in a population of unemployed persons with multiple barriers to employment almost all participants mentioned violent, abusive or disrupted family- or personal relations as barriers to employment [Citation17,Citation18].

A well-known person-centred and community-based intervention is the Family Group Conference [Citation19–22]. Family Group Conference is a network intervention by which the client, his or her family, and professionals together develop a plan to solve a problem of the client. Although Family Group Conference in its original form is mainly practice based, it is linked with several theories, such as empowerment, strength, and social network theory [Citation20]. These theories fit well with the Family Group Conference assumptions of collective responsibility, mutual obligation and shared interest, self-reliance and client-control. The Family Group Conference meeting is organized by a facilitator who, during a private session with the client and his family, creates conditions for them to work together and find solutions. Facilitators are not present during the actual conference [Citation21,Citation23,Citation24].

Family Group Conference originated from Maori cultural practice in New Zealand and was further developed for child welfare services in the late 1980s. It aims to support client empowerment by mobilizing the client’s social network, i.e., families and significant others outside the family [Citation25,Citation26]. Family Group Conference principles include collective responsibility, mutual obligation and shared interest. Self-reliance and client-control are also key concepts. The emphasis of Family Group Conference on client-empowerment and self-management corresponds well with current activation strategies encouraging unemployed persons to take their own responsibility to find work. Another important pillar of Family Group Conference is family involvement. Family and other significant others are considered better able to consider all relevant problems in order to make well-informed decisions. Families are believed to have a right to participate in decisions that affect them, and to be competent to make decisions if properly engaged, prepared and provided with necessary information [Citation21,Citation24]. These principles of family involvement seem to apply to vocational rehabilitation, since the literature shows a positive association between positive social support and return to work [Citation27–29]. Family Group Conference may thus be an effective approach to support unemployed persons receiving work disability benefit in the return to work process.

The Family Group Conference concept has spread to many Western countries [Citation30–32], including the Netherlands [Citation23,Citation33]. This approach has been used in diverse settings with vulnerable groups, e.g., minority groups [Citation34,Citation35], juvenile crime recidivists [Citation36] and longer-term social assistance recipients [Citation25,Citation26]. However, we found only one study which evaluated Family Group Conference in a setting of young adults with disabilities, about to leave school and enter the labour market [Citation37]. In that study, although the process and the plan resulting from the Family Group Conference were evaluated positively, health and participation outcomes were not reported.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the feasibility of Family Group Conference to promote return to work among unemployed persons receiving disability benefit, using Bowen’s Feasibility Framework [Citation38].

Method

Study design

To study the feasibility of the Family Group Conference for promoting return to work we conducted a pre-post-intervention mixed-method design, using Bowen’s Feasibility Framework [Citation38] to analyse relevant domains. The Medical Ethical Board of the University Medical Center of Groningen declared, in accordance with the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act [Citation39], the study to be exempt from a medical ethical review (M12.117154). This study complies with The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Scientific Practice, from the Association of Universities in the Netherlands [Citation40].

Setting

The Dutch Social Security Institute for Employee Benefits Schemes (UWV), servicing the northern region of the Netherlands, facilitated the present study in collaboration with the regional Family Group Conference organization. The Social Security Institute offers social assistance and employment services to clients receiving work disability benefits.

Participants

Participants in this study were clients, their Labour Experts from the Social Security Institute involved in guiding the clients back to work, and Family Group Conference facilitators. Participating clients enrolled after providing informed consent. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time.

Eligible clients were aged 17–65 years, receiving work disability benefit, had (partial) capacity to reintegrate into paid work according to their Labour Expert, but were not self-reliant in finding work, and mastering the Dutch language.

Since the budget for Family Group Conferences was limited and our aim was to study feasibility, we settled for a convenient sample.

Family Group Conference intervention

Facilitators were independent, trained and certified for their function by the Dutch Family Group Conference organisation. The Family Group Conferences took place in a neutral community building, from July 2012 to March 2013. A facilitator of the regional Family Group Conference organization and a staff Labour Expert at the local Social Security Institute office organised an instructional meeting for interested Labour Experts from the Social Security Institute. The Labour Experts present were provided with an instruction letter for their clients, an informed consent form, and a short written instruction. The Labour Experts introduced the Family Group Conference method to their clients and asked them to participate. Those willing to participate were then interviewed by the Family Group Conference facilitator. Interviewees willing to participate in a Family Group Conference then indicated persons in their social network who could also be invited. The facilitator then organised the invitations, a neutral location and the start-up of the Family Group Conference. The Family Group Conferences were carried out by the clients, their families, the Labour Experts from the Social Security Institute involved in the vocational rehabilitation of these clients, and the Family Group Conference facilitator. During the actual conference the facilitator was present at the location, but did not personally participate in the conference itself, nor did the Labour Expert. The Family Group Conference facilitator drafted a Return to Work Plan for each individual Family Group Conference participant. The Return to Work Plans included the following items: the main question(s) formulated in the Family Group Conference about a problem perceived by the client, the action(s) to be taken to address this problem, and the Family Group Conference participant(s) assigned to execute the action(s).

Data collection

We collected data from July 2012 to October 2013. To add strength and credibility to the findings we used information from multiple data sources [Citation41]: questionnaires for participating clients, Labour Experts and Family Group Conference facilitators, semi-structured telephone interviews, and Return to Work Plans (Return to Work Plans) drafted during the Family Group Conferences. All data were anonymised.

Using standard questionnaires from the Family Group Conference organisation, the Family Group Conferences were evaluated according to four applicable domains of the Bowen Feasibility Framework [Citation38]. These domains were: (1) demand, i.e., to what extent is Family Group Conference likely to be used, (2) acceptability, i.e., to what extent is Family Group Conference judged as satisfactory by Family Group Conference deliverers and recipients, (3) implementation, i.e., to what extent can Family Group Conference be successfully delivered to intended participants, and (4) limited Efficacy, i.e., does Family Group Conference promise to have the intended effects on health and participation. Definitions of the four domains are presented in .

Table 1. Key areas of focus, outcome of interest and data source.

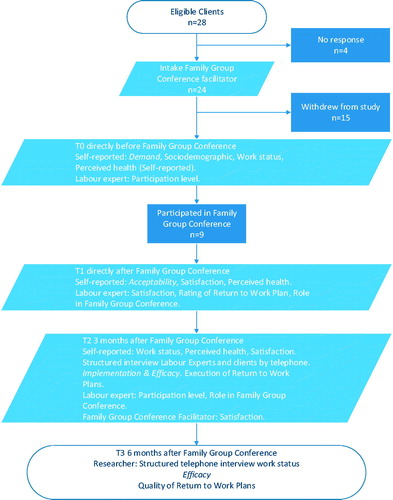

Clients filled out the questionnaire in the presence of the facilitator directly before (T0) and directly after (T1) the Family Group Conference. Furthermore, a short survey was sent to the Labour Experts. Three months after the Family Group Conference (T2) the researcher (KB) interviewed the Labour Experts and clients by telephone, and sent the facilitators a short survey to collect information they had received from participating clients, their satisfaction with the Family Group Conference and Return to Work Plan, their cooperation with the Labour Expert, and some remarks and suggestions. The qualitative semi-structured telephone interviews were summarised during the interview and verified directly with the participants. Six months after the Family Group Conference (T3) the researcher (KB) again interviewed the clients by telephone. See also the flow-diagram ().

Demand

To describe demand, we collected sociodemographic data (i.e., gender, age, educational level, urbanisation, work status, marital status, having children) of participating clients at T0. There might be sociodemographic influence on participation in a Family Group Conference. We categorised educational level into low (elementary, preparatory middle-level), intermediate (middle-level applied; higher general continued) and high (university applied sciences; research university). We categorised urbanisation into rural (<10.000 habitants), midsize urban (10.000–100.000 inhabitants) and urban (>100.000) inhabitants).

We also asked Labour Experts at T2 for the reason(s) why clients who initially agreed to participate later decided to withdraw from the study. If they did not know, we asked the facilitators.

Acceptability

Acceptability was measured by asking participating clients in the survey to assess at T1, on a 1–10 response scale, their overall satisfaction about the facilitator, the Labour Expert, the Family Group Conference, the Return to Work Plan and the Family Group Conference method. Furthermore, they were asked to rate the role of the facilitator, the Labour Expert, the Family Group Conference and the Return to Work Plan by indicating (dis)agreement with certain statements on a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5). Examples of statements were: ‘the facilitator was neutral’; ‘the information from the Labour Expert was clear’; ‘I felt at ease during the Family Group Conference’; ‘the Return to Work Plan will improve my situation’. At T2, again using a 1–10 response scale, we asked the participating clients again about their overall satisfaction with the conference and the Return to Work Plan. Acceptability for both Labour Expert and facilitator was measured according to level of satisfaction and appropriateness; they were asked on a 1–10 response scale to describe their satisfaction with their mutual collaboration during the Family Group Conference. We also asked Labour Experts and facilitators about their satisfaction with the conference and the Return to Work Plan (1–10 scale). We asked Labour Experts whether during a Family Group Conference they had received sufficient information from the facilitator on the process, content and goals of the Family Group Conference, as well as their own roles in the process. Facilitators were asked if they had received sufficient information from the Social Security Institute, whether the questions for a Family Group Conference were clear, whether the involvement of the Labour Expert in the preparation stage was sufficient, and whether the client was well informed about the Family Group Conference. The answers were assessed using a five point Likert scale from totally disagree to totally agree. Furthermore the facilitators were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 10 the Family Group Conference, the cooperation with the Labour Expert/Social Security Institute and the Family Group Conference plan.

Implementation

Regarding implementation, by means of telephone interviews at T2, data were gathered as to whether or not the Return to Work Plan had been executed and whether any adjustments in the Return to Work Plan had been made. Execution was assessed by asking ‘Did you execute the plan?’ Five answer categories were given: I don’t know (1), the whole plan has been executed (2), the plan has not been executed at all (3), the plan has been executed to some extent (4), I don’t understand the question (5). The extent of execution of the Return to Work Plan was assessed by asking ‘How many of the actions of the plan were executed?’ Six answer options were given: more than half (1), half (2), less than half (3), I don’t know (4), other (5), I don’t understand the question (6). To assess the success of the implementation of the Return to Work Plan, clients were asked whether it had resulted in any changes. We presented participating clients with 10 statements, asking (dis)agreement on a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree or disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5) and one answer option (I don’t understand the question (6). Implementation at the Labour Expert level was measured both at T1 and T2 by asking the experts to rate the Return to Work Plan and their own role during the Family Group Conference, also by indicating (dis)agreement with statements on a 1–5 point Likert scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree or disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5). Examples of statements were: ‘I have more faith in my clients’ future’, ‘the plan will work’ and ‘I am satisfied about my part in the Family Group Conference’.

Efficacy

Efficacy was measured by means of changes in perceived health and/or work status, and by analysing the Return to Work Plans during follow-up.

Perceived health was measured at T0 and T1, using the 12-item Short Form health survey (SF-12) [Citation42], a practical, reliable, valid and brief inventory of physical and mental health. SF-12 scores were recoded, standardised to a 0–100 scale and, using a syntax included in the SF-12 manual, summarised into two summary scores [Citation42]: Physical Health Composite Scores (PCS) and Mental Health Composite Scores (MCS). Higher scores indicate better health. A PCS score ≤50 is indicative of lower physical health and a MCS ≤42 indicates lower mental health.

At T3 work status was assessed in a telephone interview with the following questions: ‘Do you work?’ (yes/no)’; ’If yes, for how many hours?’; ‘Is the work temporary?’ (yes/no); ‘If yes, for how long?’; ‘Is it voluntary or paid work?’; ‘Do you think that it is because of the Family Group Conference that you are working?’ (yes/no); ‘Are you still working on the Return to Work Plan?’ (yes/no); ‘When you are not working, what activities are you doing, for how many hours per day/week, and are these a result of the Return to Work Plan?’

To further evaluate efficacy the researchers (KB, JH) independently read and coded the Return to Work Plans drafted by the Family Group Conference facilitators on the following items: the main question(s) formulated by Family Group Conference participating clients, the necessary action(s) to take, and the Family Group Conference participant(s) assigned to perform these action(s). Questions formulated in the Return to Work Plans were categorized as health-, person- and environment-related, according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model [Citation43].

Further for Efficacy, at T0 and T2 Labour Experts filled out the Participation Ladder [Citation44], a Dutch scale for grading the level of client participation [Citation44]. This measure, widely used by social services of municipalities in the Netherlands, rates participation on six levels: social exclusion (step 1), some social participation (step 2), participation in organised activities (step 3), unpaid work (step 4), paid work with support (step 5) and regular paid work (step 6).

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis

To describe outcomes on demand, acceptability, implementation and limited efficacy testing, we performed simple descriptive statistics (percentages, mean, standard deviation and range), using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS statistics, Armonk, NY). Agreement of participants with statements was dichotomized into agree (scores 4 and 5) and disagree (scores 1–3).

Qualitative data analysis

The Return to Work Plans and interview data were analysed according to the principles of thematic analysis [Citation45]. Return to Work Plans were coded by a mixed team of two researchers: researcher and first author KB, a male PhD student, psychologist and experienced Labour Expert; and JH, a female sociologist, research assistant and marketing researcher. The interviews were analysed by KB and PR, the latter a male health scientist with a PhD in the field of work and health, and with experience in qualitative research. Individual coders used open coding with comment functions in word processing software. Coded texts and emerging relationships between codes were discussed among the authors. Individual coding was discussed to reach consensus about the codes and emerging themes. No final member check of themes took place.

Results

Demand

The Labour Experts selected a total of twenty-eight clients eligible for a Family Group Conference. All were approached by a Family Group Conference facilitator for an intake interview and a consecutive Family Group Conference. Facilitators were unable to contact four clients. Of the twenty-eight eligible clients nine (32.1%) clients recruited by seven Labour Experts participated in an actual Family Group Conference led by a total of six Family Group Conference facilitators; see .

The socio-demographic characteristics of the recruited clients participating and non-participating in a Family Group Conference are presented in . Participants were slightly older than non-participants (34.7 versus 32.6 years), more often female (55.6 versus 42.1%), more highly educated (intermediate education 55.6 versus 36.9%), and living more often in rural and urban settings. The participation level, as assessed by the Labour Experts, differs slightly between the two groups (2.6 versus 2.9, not in table).

Table 2. Baseline demographic characteristics of participants and non-participants in Family Group Conference.

The Family Group Conference facilitators and Labour Experts were asked to give reason(s) why 19 clients who initially agreed to participate later decided to withdraw from the study. The reasons were diverse: six clients could not be contacted; three clients stated that their social network was too small for a Family Group Conference; facilitator 5 stated “very small social network and client refused”; facilitator 13 stated “client wanted support from the Social Security Institute but did not want to involve his own network”; three clients declined to participate due to health problems; three clients gave other activities as reasons not to participate; two clients had no trust in institutions. In the remaining two cases, the reasons for withdrawal were unknown. According to the facilitators, the main reasons for rejection of a Family Group Conference were unclear goals and expectations, resistance to network involvement, and target client’s doubt about its applicability for themselves.

Acceptability

The overall satisfaction score of participating clients about the Family Group Conference facilitator was on average 6.6 (SD 2.2; range 3–10). They all considered the facilitator to be neutral and independent. Client 15 stated: “pleasant experience. Plan is a step in the right direction,” client 19 stated: “in general positive” but also client 27 stated: “the coordinator nags too much” and client 9 stated: “coordinator has no fit with the clients.” The overall satisfaction score about the Labour Expert was on average 7.4 (SD 1.2; range 5–9). Most participating clients considered the information given by the Labour Expert to be relevant and clear. At T1 the mean overall rating by all participating clients of the Family Group Conference was 7.1 (SD 1.6; range 4–9), and at T2 the mean overall rating was 7.0 (SD 1.9; range 3–9). Eight participating clients evaluated the acceptability of the Family Group Conferences based on nine positively formulated statements (). At T1, most participating clients agreed with the 16 statements about the Return to Work Plan. The mean overall rating of the Return to Work Plan at T1 was 6.9, (SD 1.8; range 3–8), and the mean overall rating at T2 was 7.7 (SD 0.8; range 7–9).

Table 3. Participants’ (n = 8) evaluation of labour experts, Family Group Conference, and Return to Work Plan directly after Family Group Conference (T1).

The Labour Experts rated their satisfaction about the collaboration with the Family Group Conference facilitator with a 6.8 (SD 2.1; range 4–9). The Family Group Conference facilitators rated their satisfaction with the Labour Expert with a 6.3 (SD 2.5; range 1–10), the Return to Work Plan with a 7.1 (SD 1.4; range 6–9) and the Family Group Conference with a 7.2 (SD 1.6; range 4–9). At T1 the Labour Experts rated their satisfaction with the Return to Work Plans with a 6.6 (SD 1.68; range 3–8) and at T2 with a 6.3 (SD 2.49; range 1–8). At T1 they rated the Family Group Conference with a 7.4 (SD 0.78; range 6–8) and at T2 with a 7 (SD 1.91; range 3–9).

Implementation

In all nine Family Group Conferences, a Return to Work Plan was drafted. Three months after the Family Group Conference, six (77.8%) participating clients reported that the Return to Work Plan made in the Family Group Conference had been executed in full (n = 3) or to some extent (n = 3). One client did not know whether the Return to Work Plan had been executed and information of two clients is missing. Of the six clients who reported that the Return to Work Plan had been (partially) executed, five clients reported that half or more of the actions of the plan had been executed and one client reported that fewer than half of the plan actions had been executed. Four of six clients indicated that the Return to Work Plan made in the Family Group Conference was not later adjusted. All six clients stated that the Return to Work Plan had improved their situation. Four clients reported having more confidence in the future, asking sooner for help from their social network, having more self-confidence, and being better able to cope with their situation; see .

Table 4. Participants’ (n = 6) opinions on changes due to Return to Work Plan, three months (T2) after Family Group Conference.

Some clients felt a mismatch between the approach/knowledge of the facilitator and their own situation. ‘The facilitator has no insight into the target population’, Client 3. ‘The facilitator did not connect with the target population’; ‘the approach must be more pragmatic’ Client 9.

Limited efficacy testing

Perceived health

At baseline (T0), the mean PCS was 42.1 (SD 5.9; range 36.1–50.5) and the mean MCS was 40.9 (SD 6.9; range 28.9–51.9). At T1, the mean PCS was 41.9 (SD 10.3; range 24.9–54.8) and the mean MCS was 42.9 (SD 9.1; range 31.9–56.5).

Level of participation

At T0 the mean Participation Ladder level was 2.6 for nine participating clients (SD 0.7; range 1–3). At T1, the mean Participation Ladder level was 3 for all four reported clients.

Work status

Eight participating clients were available for follow-up questions on work status six months after the Family Group Conference. A total of five out of eight had entered (voluntary) work. One client had a full time job, one client started a company of his/her own, three clients started voluntary work, one client returned to school, and one was engaged full-time in household activities. The person who started a company and the two who started voluntary work reported that their employment was due to the Family Group Conference. One client reported not being able to do any regular work.

Results from the Return to Work Plans

In all nine Family Group Conferences, a Return to Work Plan was drafted, to which in total 57 persons (on average 6.3 per Family Group Conference) from the social network of the participating client contributed. Most of the main questions formulated during the Family Group Conference were work related, for instance: ‘What do I need to find suitable work?’; ‘How can I use my creative talents in paid work?’ In one Family Group Conference the main question was related to a personal problem: ‘How can I better manage my life and make better choices?’ In all Family Group Conferences actions were drawn up in response to these questions. Most actions were work related, for instance: monitor job opportunities, apply for jobs, find a relevant course, and find professional support. In two Family Group Conferences actions were both person and environment related, for instance: structure household, find transportation support, enhance self-confidence, and travel alone. In total, 43 persons (on average 4.8 per Family Group Conference) participating in the Family Group Conference, in most cases including the participant himself, were chosen to take some action. Other actors frequently assigned to take action were: partner, parents, other blood relatives, and friends. In five Family Group Conferences the actor was a professional from the Social Security Institute or a reintegration agency.

Discussion

The main findings of this study show that Family Group Conference may be a feasible approach for a selected group of persons on disability benefits. One out of three persons on full or partial disability benefit actually participated in a Family Group Conference; i.e., the degree of participation was 32.1%. Clients participating in a Family Group Conference seem to be more highly educated than clients not participating in an Family Group Conference. Between participating and non-participating clients we found slight differences in age and gender. As for acceptability, directly after the Family Group Conference the overall client satisfaction with their Family Group Conference, the Return to Work Plan, the Family Group Conference facilitator and the Labour Expert was promising. Moreover, both facilitators and Labour Experts were satisfied about the Family Group Conferences, the Return to Work Plans, and their mutual collaboration. As for implementation, almost all Return to Work Plans made in the Family Group Conferences were successfully delivered to intended recipients as planned. As for efficacy, in the period between start and finish of the Family Group Conference the results indicate a slight improvement in perceived mental health and level of participation. Six months after the Family Group Conference five clients participated in paid or voluntary work; three of them reported that this was a result of their Family Group Conference. Qualitative analysis of the Return to Work Plans showed that most questions and related problems, as well as planned actions, were work related. Furthermore, the actor most frequently chosen to take action was the participant himself, supported by family members and significant others in- and outside the family.

Our findings on the demand for Family Group Conference are more or less in line with other studies on Family Group Conference in (young) adult settings: an actual Family Group Conference took place in 38% [Citation25] and 41.2% [Citation37] of all eligible participants. Three clients eligible to participate stated that their social network was too small to organize a Family Group Conference. Non-existent or very poor social network was also found to be a reason for non-response in 10% of cases in the above-mentioned study [Citation25]. One might argue that a social network with a sufficient number of significant others able and willing to provide social support is crucial for any Family Group Conference, and without it a Family Group Conference is not feasible. However, according to experts in the field interviewed in a Dutch study on the applicability of Family Group Conference in mental health care, organising a Family Group Conference is always of value to restore contact with family members. Moreover, a limited network is a particularly good reason for organising a Family Group Conference, and there is always a network that can be used, even though tired or paralyzed [Citation23]. According to Sissel-Johansen [Citation26] the central function of Family Group Conference for recipients of social assistance seems to be reconnecting the social network so as to reduce loneliness and increase the availability of support [Citation26].

Three eligible clients reported that they could not participate due to reported health problems. This study does not provide information on the nature, i.e., mental or physical or both, nor on the severity of these health problems. According to experts interviewed in the aforementioned Dutch study, organising a Family Group Conference during a severe mental health crisis, like psychosis or drug misuse, is usually of limited value or even counterproductive [Citation23]. For people with severe mental illness, Individual Placement and Support might more effectively result in paid employment and thus be preferred above Family Group Conference. Individual Placement and Support is an evidence-based approach with proven efficacy in helping people with severe mental illness to achieve steady employment in competitive jobs [Citation46]. In contrast with Family Group Conference, Individual Placement and Support leans strongly on professionals and is therefore more expensive and seems less feasible for large groups. For the less severely disabled a Family Group Conference aimed at return to work might be an alternative.

We found an indication that clients participating in a Family Group Conference were more highly educated than clients not participating in an Family Group Conference. Although Labour Experts were informed by the researcher (KB) that recipients of work disability benefits should be invited to participate in the study regardless of their educational level, recruitment by Labour Experts may have been selective, favouring persons with a higher education to actually participate in a Family Group Conference. In the aforementioned Norwegian study among longer-term social assistance recipients, selective recruitment of participants also played a role. However, in that study social workers seemed to favour people with a low educational status [Citation25].

Our findings on acceptability in terms of satisfaction, and on implementation, are in line with studies conducted in other settings. In those studies, satisfaction on the part of participating clients about the Family Group Conference process ranges from encouraging [Citation47] to very positive [Citation25,Citation48].

As for short-term efficacy, in the period between the start and the completion of the Family Group Conference we found a small positive change in perceived mental health and level of participation of participating clients. Similar findings were reported in an intervention study among adults receiving social assistance in Norway [Citation25]; data indicated a decrease in mental distress, anxiety and depression 22 weeks after the Family Group Conference. In our study, six months after the Family Group Conference five clients reported to be in paid employment or doing voluntary work. Three clients reported that this was a result of their Family Group Conference, although other possible factors cannot be excluded.

In all Family Group Conferences clients were supported by family members and significant others outside the family (e.g., friends). All Family Group Conferences resulted in Return to Work Plans, and analysis of these plans showed that almost all actions were aimed at return to work. It seems that the starting point in the Family Group Conferences was to help the participant to help himself get back into paid work, and to give support where necessary. Our study further indicates that involvement of the social network may have added value for vocational rehabilitation of persons on disability benefit. This is in line with findings of studies conducted in other disadvantaged groups [Citation9–15].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the feasibility of Family Group Conference to promote return to work among persons receiving work disability benefit. The study builds on an established set of key areas of focus to determine feasibility, thereby helping to determine whether Family Group Conference, as an innovative approach for persons on work disability benefit, is worth consideration for further development, as well as for more extensive research into its effectivity. A strength of our study is the use of different data sources from the perspective of clients and their social network, Labour Experts and Family Group Conference facilitators. Strong consistency was observed between these qualitative and quantitative findings.

Several limitations should be noted. As is inherent in any feasibility study, ours was limited in both scale and scope. The findings should therefore be interpreted with caution. We did not employ a comparison group, and the number of participating clients was limited. Due to small sample sizes we did not statistically test differences between participating and non-participating clients, nor changes within participating clients. The recruitment of eligible clients by Labour Experts may have been selective, favouring persons with a higher education in order to actually have a Family Group Conference. This may have resulted in selection bias, since more highly educated persons on work disability benefit are likely to return to work sooner than less educated persons [Citation28]. The outcomes of this study may also have been influenced by the level of cultural competence of the Family Group Conference facilitators and Labour Experts in dealing with clients and their families [Citation49]. Lack of cultural competence may, for example, have resulted in less than optimal family involvement. Finally, on some outcomes the response of clients was limited: one of the nine participating clients only filled out the survey at T0, and for five clients the level of participation at T1 was missing.

Conclusion

This study shows the potential for using Family Group Conference as an innovative approach aimed at return to work for a selected group of persons on disability benefit. Acceptability and implementation were well evaluated. As for long-term efficacy of Family Group Conference, we found small positive changes in perceived mental health and participation. All Family Group Conferences resulted in actions aimed at return to work. Based on our findings, we carefully conclude that involvement of the social network may have added value in the return to work process of clients on work disability benefit. Family Group Conference represents a promising supplementary programme to be used in activation strategies to enhance return to work of persons with disabilities. Family Group Conference warrants further testing in a larger study to assess the potential success of its implementation, and uncover and reduce possible threats to validity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participating clients and professionals for their kind cooperation. The authors would also like to thank research assistant Jeanique Ham for her valuable contribution in logistics, organisation and administration.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. Transforming disability into ability. Policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. Paris: OECD Publications; 2003.

- OECD Employment Outlook. Activating the unemployed: what countries do. Chapter 5. Paris: OECD publishing; 2007.

- OECD. Sickness, Disability and Work: keeping on track in the economic downturn: background paper. Stockholm: OECD; 2009.

- Doorslaer E, Koolman X. Explaining the differences in income‐related health inequalities across European countries. Health Econ. 2004;13:609–628.

- Schuring M, Mackenbach J, Voorham T, et al. The effect of re-employment on perceived health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:639–644.

- Carlier BE, Schuring M, Lötters FJ, et al. The influence of re-employment on quality of life and self-rated health, a longitudinal study among unemployed persons in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2013;13:503.

- World Health Organization, World Bank. World report on disability. Malta: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Bosselaar H, Maurits E, Molenaar-Cox P, et al. Clients with multiple problems. An orientation and report in relation to (labour)participation. [Multiproblematiek bij cliënten. Verslag van een verkenning in relatie tot (arbeids)participatie]. Utrecht/Leiden:Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment; 2010. Dutch.

- Jetha A, Badley E, Beaton D, et al. Transitioning to employment with a rheumatic disease: the role of independence, overprotection, and social support. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:2386–2394.

- Wagner S, White M, Schultz I, et al. Modifiable worker risk factors contributing to workplace absence: a stakeholder-centred best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Work. 2014;49:541–558.

- Shaw WS, Campbell P, Nelson CC, et al. Effects of workplace, family and cultural influences on low back pain: what opportunities exist to address social factors in general consultations? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:637–648.

- Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14 Suppl 3:S8.

- Brouwer S, Reneman MF, Bültmann U, et al. A prospective study of return to work across health conditions: perceived work attitude, self-efficacy and perceived social support. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:104–112.

- Danziger S, Corcoran M, Danziger S, et al. Work, income, and material hardship after welfare reform. J Consumer Aff. 2000;34:6–30.

- Anderson SG, Halter AP, Gryzlak BM. Difficulties after leaving TANF: inner-city women talk about reasons for returning to welfare. Soc Work. 2004;49:185–194.

- Furlong A, Cartmel F. Vulnerable young men in fragile labour markets: employment, unemployment and the search for long-term security. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2004.

- Dean H, MacNeill V, Melrose M. Ready to work? Understanding the experiences of people with multiple problems and needs. Benefits. 2003;11:19–25.

- Dean H. Re-conceptualising welfare-to-work for people with multiple problems and needs. J Soc Pol. 2003;32:441–459.

- Hayden C. Family Group Conferences—are they an effective and viable way of working with attendance and behaviour problems in schools? Br Educ Res J. 2009;35:205–220.

- Metze RN, Abma TA, Kwekkeboom RH. Family group conferencing: a theoretical underpinning. Health Care Anal. 2015;23:165–180.

- Crampton D. Research Review: Family group decision‐making: a promising practice in need of more programme theory and research. Child Fam Soc Work. 2007;12:202–209.

- Wright T. Using family group conference in mental health. Nurs Times. 2008;104:34–35.

- Jong G, Schout G. Family group conferences in public mental health care: An exploration of opportunities. Int J Mental Health Nurs. 2011;20:63–74.

- Huntsman L. Family group conferencing in a child welfare context. Ashfield: Centre for Parenting & Research, Department of Community Services; 2006.

- Malmberg-Heimonen I. The effects of Family Group Conferences on social support and mental health for longer-term social assistance recipients in Norway. Br J Soc Work. 2011;41:949–967.

- Johansen S. Psycho-social processes and outcomes of family group conferences for long-term social assistance recipients. Br J Soc Work. 2012;44(1):145-162.

- Brouwer S, Krol B, Reneman MF, et al. Behavioral determinants as predictors of return to work after long-term sickness absence: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:166–174.

- Krause N, Dasinger LK, Deegan LJ, et al. Psychosocial job factors and return‐to‐work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase‐specific analysis. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:374–392.

- Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, et al. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:591–598.

- Sieppert JD, Hudson J, Unrau Y. Family group conferencing in child welfare: lessons from a demonstration project. Fam Soc. 2000;81:382–391.

- Merkel-Holguin L. Sharing power with the people: family group conferencing as a democratic experiment. J Soc Soc Welfare. 2004;31:155.

- Marsh P, Crow G. Family group conferences in child welfare. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998.

- Jong G, Schout G. Breaking through marginalisation in public mental health care with Family Group Conferencing: shame as risk and protective factor. Br J Soc Work. 2012;43(7):1439–1454.

- O'Shaughnessy R, Collins C, Fatimilehin I. Building bridges in Liverpool: Exploring the use of Family Group Conferences for black and minority ethnic children and their families. Br J Soc Work. 2010;40:2034–2049.

- Chand A, Thoburn J. Research review: child and family support services with minority ethnic families: what can we learn from research? Child Fam Soc Work. 2005;10:169–178.

- Baffour TD. Ethnic and gender differences in offending patterns: examining family group conferencing interventions among at-risk adolescents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2006;23:557–578.

- Spierenburg M, Cuijpers M, van Lieshout H, et al. Met Eigen Kracht naar een baan. Een experiment met Eigen Kracht-conferenties bij de start van de loopbaan van jongeren met een beperking. 2007.

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:452–457.

- Ministery of HWS. Dutch medical research involving human subjects act (WMO). International Publication Series Health, Welfare and Sport. 1997;2:1–34.

- Association of Universities in the Netherlands. The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Scientific Practice Association of Universities in the Netherlands. The Hague: VSNU; 2012.

- Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13:544–559.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston (MA): The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, second edition, 1995.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Horssen C. v, Mallee L. Testing the participation ladder. Experiences from six municipalities. [De participatieladdder getest. Ervaringen van zes gemeenten]. Amsterdam; 2009. Dutch.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Drake RE, Bond GR. IPS support employment: a 20-year update. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2011;14:155–164.

- Sundell K, Vinnerljung B. Outcomes of family group conferencing in Sweden. A 3-year follow-up. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:267–287.

- Holland S, O’Neill S. ‘We had to be there to make sure it was what we wanted’Enabling children’s participation in family decision-making through the family group conference. Childhood. 2006;13:91–111.

- Barn R, Das C. Family group conferences and cultural competence in social work. Br J Soc Work. 2016;46:942–959.