Abstract

Purpose: The inclusion of rehabilitation clients with communication and/or cognitive impairments after stroke in person-centred goal-setting is challenging. Moreover, this group of clients has largely been excluded from studies, resulting in a lack of knowledge about how to optimize their participation. The aim of this study was to explore strategies that are used in rehabilitation to involve stroke survivors with communication and/or cognitive impairment in person-centred goal-setting.

Materials and methods: Eleven stroke rehabilitation professionals participated in semi-structured in-depth interviews. Thematic analysis was undertaken to describe their practice-based strategies.

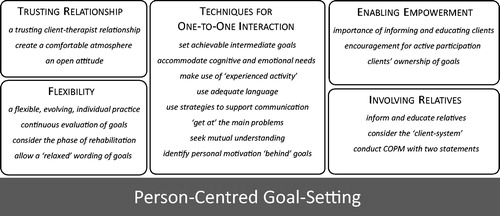

Results: Twenty-one aspects of person-centred goal setting were described from the data and grouped according to five themes: flexibility, trusting relationships, enabling empowerment, techniques for one-to-one interaction, and involving relatives. Participants did not distinguish between approaches for clients with either communication or cognitive impairments but drew from a repertoire of strategies to best meet the individual person’s needs. Participants’ practice combined the conscientious and deliberate application of various strategies with a mind-set that it is possible to involve clients with communication and cognitive impairments in person-centred goal-setting.

Conclusions: These findings offer insights into inclusive person-centred goal-setting practices, based on accounts from a group of experienced rehabilitation clinicians.

The goal-setting process is not rigid, but an evolving and individual practice, and should be individually adapted to the (changing) needs of the client during the continuum of rehabilitation.

In practice, strategies tend not to be distinguished into those supporting communication and those supporting cognitive difficulty; but strategies are applied flexibly and in combination, to meet the needs of the individual client.

It is important to provide specific and sufficient support as well as enough time to enable participation for clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment in goal-setting.

Leaving one’s own values, preferences, attitudes and notions of “normality” behind can help rehabilitation practitioners to get to know the client, be sensitive towards all signs the client offers during a conversation, and remain open to differing and alternative viewpoints when considering goals.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of disability worldwide [Citation1]. Due to functional deficits, stroke survivors often experience limitations in activity and participation, which can lead to social isolation and further negative health events [Citation2]. Rehabilitation plays an important part in counteracting these negative consequences of stroke.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation3] has introduced a shift towards a biopsychosocial understanding of illness [Citation4]. As a result, health professionals acknowledge that clients bring with them a unique set of values, preferences, attitudes and conditions, which are related to their personal history and their social and physical environment [Citation4]. In rehabilitation, this has led to an emphasis on addressing people’s biopsychosocial needs and their social and environmental contexts, which can be achieved through person-centred goal-setting [Citation3,Citation5,Citation6].

Goal-setting has become standard practice in rehabilitation, as a way of generating outcome expectations and prioritizing rehabilitation activities, but there are different approaches to its implementation [Citation7–10]. Similarly, understandings and interpretations of person-centredness differ to some extent, and various terms have been used to express the concept: patient-, client-, person-, individual-/-centred, -orientated, -focused, -directed. Four common dimensions of person-centredness have been described as: (a) addressing the person’s specific and holistic properties, (b) addressing the person’s difficulties in everyday life, (c) the person as an expert: participation and empowerment, and (d) respecting the person “behind” the impairment or disease [Citation6].

Several studies have investigated client involvement during goal-setting in rehabilitation. A recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that client involvement in goal-setting contributes to subjective client outcomes such as motivation, quality of life and self-efficacy [Citation11]. Another systematic review by Rose et al. described that including clients in the goal-setting process results in improved confidence and a sense of ownership, which can increase motivation to achieve goals and impacts positively on rehabilitation [Citation12]. But the literature also describes reasons and circumstances when clients do not want, or do not feel ready to participate in goal-setting: requiring time to reflect, lack of knowledge around stroke recovery and goal-setting, inability to process the questions asked, reluctance to share personal goals with others, feeling obliged to take a passive role, fear of challenging professional power or knowledge, perceiving staff as being stressed, and assuming that verbal expression is the only possible way to participate [Citation13–16]. As Rosewilliam, Pandyan, and Roskell stated, good goal-setting practice considers contrasting client attitudes, and it is therefore necessary to explore clients’ preferences to participate [Citation17]. Furthermore, Playford suggested that, when clients demonstrate passivity during decision-making, the reasons for this should be considered [Citation4]. Studies have shown that to enable participation (including for clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment), health professionals need to provide support that is both specific and sufficient [Citation13,Citation18–20].

However, also when clients are able to and would like to be involved, goal-setting is often not conducted in a person-centred way [Citation21–24]. The main barriers identified in the literature relate to mismatch between client and staff perspectives, clinicians’ lack of confidence to manage client expectations, clients’ stroke related impairments, insufficient time, and ineffective organizational systems [Citation25]. The literature describes some approaches to overcome these barriers, such as tailoring the goal-setting process individually to clients’ preferences, strategies to promote communication and understanding of goal-setting, and sufficient time and expertise [Citation25,Citation26]. But clients with communication and/or cognitive disorders have largely been excluded from these studies, resulting in a lack of knowledge about how to optimize participation in rehabilitation goal-setting for these groups [Citation27,Citation28].

Communication and cognitive disorders are common after stroke and therefore pose a considerable challenge to goal-setting. Some studies demonstrate how, given the appropriate support, clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment can actively participate in the goal-setting process [Citation18,Citation28–31]. It has been asserted that professionals require a high level of skill and experience to realize person-centred goal-planning [Citation32], yet clinicians often express a lack of strategies or tools to implement it [Citation22]. In response to these clinician-related barriers, authors agree that there is an urgent need to further discover and describe strategies for involving clients with communication and/or cognitive disorders in person-centred goal-setting [Citation13,Citation18,Citation32].

To address this gap, this study aimed to explore and describe practice-based strategies for involving stroke survivors with communication and/or cognitive impairment in person-centred goal-setting.

Method

Research design

This study used a qualitative design with semi-structured in-depth interviews and thematic analysis, to describe self-reported practice-based strategies from health professionals’ clinical experience.

Participants and recruitment

Recruitment took place in Austria from December 2016 to March 2017. Eligible were health professionals from the following disciplines: physicians, allied health professionals (occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists) and psychologists. Participants had to have at least two years of clinical work experience with a focus on person-centred goal-setting processes in the rehabilitation of stroke survivors. They had to express personal commitment to involving people with communication and cognitive impairment in goal-planning. To screen against inclusion criteria, the researcher had preliminary discussions with potential participants prior to the interview, in person or per email.

Snowball sampling was used to purposively identify key informants [Citation33]. The first author (ED) initially approached two former work colleagues, who then suggested further professionals engaged in advanced training in goal-setting and person-centred practice. Overall, sixteen individuals were contacted per email or in person, out of whom thirteen expressed interest in the study. One person was excluded because of insufficient work experience in stroke rehabilitation, and twelve were invited to give an interview. One interview was subsequently excluded from the dataset, because it became apparent during the interview that the participant had insufficient experience and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria. Eleven interviews were used for data analysis.

Data collection

For participants’ convenience, interviews were conducted face-to-face, via telephone, or video call online. ED conducted all interviews. A semi-structured interview schedule was used (). The interview schedule was piloted with a professional who was familiar with the topic. Minor amendments were made for clarity, but overall the interview schedule was considered appropriate for eliciting the desired content. Prior to the interview, participants received a worksheet to prompt reflection on their experience and practice, in preparation for the interview. Interviews were audio-taped and lasted on average 48 min (range 32 to 57 min).

Table 1. Semi-structured interview schedule (authors’ translation from the original German).

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by ED [Citation34]. All participants and interview transcripts were anonymised and given a participant code. Where queries emerged during the transcription process, clarification was sought from participants via telephone or email and the transcripts were amended. Data were analyzed by ED using thematic analysis [Citation35]. Transcripts were read repeatedly and analyzed using MAXQDA computer software (Version 12.3.1, 1995–2017, VERBI GmbH, Germany) and manual analysis techniques (handwritten memos, mind-mapping, and cards with codes which were placed and grouped according to themes). Passages describing strategies for facilitating person-centred goal-setting were coded, categorized and re-checked against the entire data set.

Rigor

Strategies to enhance trustworthiness included member-checking, peer review and researcher reflexivity [Citation36]. Summaries of analyses of individual interviews were emailed to participants, who were invited to review and amend. Peer review was conducted by STK, who compared a sub-sample of coded transcripts against the proposed theme structure. Researcher reflexivity was important, due to ED’s professional background as an occupational therapist in neurological rehabilitation. There was the potential that ED’s collegial relationship with some of the participants in the study, and her personal experience of goal-setting could have influenced the research process. ED enacted researcher reflexivity by raising her own awareness of these issues to reduce potential bias. ED focused on conducting research activities in a neutral manner and placing equal value on participants’ differing views and experiences. Regular debriefing meetings with the coauthor ensured decisions could be reflected on, evaluated and defended [Citation36].

Ethics

At the time of conducting this research, Austrian research governance did not require that studies involving key informant (expert) interviews with health professionals undergo formal review by a research ethics committee. Ethical research standards were adhered to and overseen by faculty at FH Campus Vienna, Austria, where the study was conducted. Study participation was entirely voluntary. All participants were provided with an information sheet and had time to consider the study and opportunity to ask questions. All participants provided written informed consent to take part, including publication of anonymised direct quotes. Participants retained the right to withdraw without giving a reason and without incurring any negative consequences.

Results

Participants

The sample consisted of eleven stroke rehabilitation professionals from a range of employment settings (). Interviewees’ responses demonstrated participants’ knowledge, awareness and application in practice of a person-centred approach to goal-setting. [Citation5,Citation6] For example, participants talked about focusing on clients and their wishes and needs; taking clients’ priorities seriously; and giving clients control in decisions about the process:

To look at the client as an individual, to try to get to know him [sic], to find out what is important for him in his life and his personality. (SLT2)

The deficits that I see, that I’m trying to put those into the background, and to see what really stands in the foreground for the patient and has priority. (PSY1)

That the person can show who he is, without one somehow exerting an influence, […] to be on an equal level with the client. […] I see myself more as a supporter. (OT5)

Table 2. Participant characteristics.

Themes

Twenty-one aspects of person-centred goal setting were described from the data and grouped according to five themes: flexibility, trusting relationships, enabling empowerment, techniques for one-to-one interaction, and involving relatives (). In the following, these five themes and corresponding aspects/sub-themes are described and supported with anonymised participant quotes, which have been translated from the original German by the authors.

Flexibility

Participants conveyed how their practice was guided by the overarching ethos that person-centred goal-setting was not only desirable, but principally possible in stroke clients with cognitive and/or communication impairment. To realize such a goal-setting practice, the process should not be viewed as rigid, but rather as a flexible, evolving and individual practice that might take anywhere from five minutes to several therapy sessions:

Some need more time. […] If one is a little bit more directive, you often realize at the end that one wasn’t on the same page, that the client had a different expectation. […] Therefore, I allow myself to really take time for this goal-setting process. (OT5)

As clients’ personal needs may change during rehabilitation, participants considered it important to adjust goals when necessary. Therefore, continuous evaluation of goals was considered essential: “If one realizes, that this goal isn’t achievable, or the goal is overwhelming for the client, then it could well be that one adapts the goal during the therapy.” (PSY1)

Several participants described, that it can be useful to consider the phase of rehabilitation and the experiences clients have made in their daily routines, to understand and support them, and to identify adequate goals. In the early stages, clients often start by discovering the consequences of the stroke: “[…] it’s about the patient getting to understand, what can I do? What can’t I do? What matters most to me at all?” (OT3). Subsequently, the focus often shifts to experiencing daily routines and (re)learning to negotiate these. As part of this process, clients often realize or reflect on what is important to them, and goals become more concrete, usually on an activity or a participation level. Health professionals could support the process of self-discovery flexibly according to the phase of rehabilitation, for example by providing clients with adequate support for functional limitations and offering clients activities to discover strengths and weaknesses.

Some participants described the advantages of a “relaxed” wording of goals, and that it is not always appropriate to formulate goals according to all SMART-criteria. SMART is an acronym that describes how goals should be worded in a particular way, so that they are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-specific [Citation37]. Participants suggested that more flexibility in goal formulation would allow for more freedom to react to clients’ changing needs; and that discarding SMART-criteria could facilitate daily routines by saving time:

I don’t have the impression that in this way our goal-setting process is less effective or less meaningful or less client-centred, if one doesn’t use [all SMART criteria], not in such a strict way at least. I think it’s right to bear this in mind. (OT5)

Trusting relationships

Most participants stressed the importance of establishing a trusting client-therapist relationship. This involved showing sincere interest in the client and their individual situation and making an effort to get to know the person. Participants described it as useful to take a calm and relaxed attitude, to build a dialog (as opposed to directing the conversation), and to make decisions together: “Create mutual trust, where the people know that they are in good hands and that they are being accepted and taken seriously and appreciated, also with their deficits.” (OT1)

Participants described the need to create a comfortable atmosphere during the goal-setting dialog. To achieve this, health professionals should be patient and give clients the time they need to understand the questions and the situation, and to reflect and express themselves. Further, several participants agreed about tailoring the dialog to avoid overwhelming the client, not only with respect to communication and cognitive issues, but also “from a psychological point of view or with respect to mood” (PSY1). One participant described giving examples of other clients in similar situations, to minimize potential shame or embarrassment with respect to clients’ limitations or goals.

Several participants also emphasized the importance of encountering the client and their situation with an open attitude, not using “ready-made schemata, [but to] be open for surprises” (PSY2). As one participant stated, “It is really important to be present with the heart, […] to listen with the heart.” (OT3)

Enabling empowerment

Participants discussed that by default, clients generally hold little decisional power in a medical setting. Therefore, it was considered important to create an environment in which clients could make their own decisions within their rehabilitation and their lives, thereby enabling autonomy: “Quality of life increases, especially when the patient can decide himself where he wants help and where not – [this is] subjectively experienced autonomy.” (OT3)

To enable autonomy, participants emphasized the importance of informing and educating clients about stroke and its possible consequences, goal-setting, treatment options and the link between therapy interventions and agreed goals. This increased understanding of their situation and the inner workings of rehabilitation, the “power of knowledge”, was thought to support and empower clients. Furthermore, participants described encouraging clients to take an active part in the goal-setting process and to reflect on meaningful goals. It was considered important to emphasize to clients that they have ownership of their goals and “nothing will be forced”, i.e., that health professionals will respect the direction clients wish to take. To reinforce this point, several participants described seeking clients’ explicit approval for each goal. Additionally, one participant described handing over goal records to clients. This made goals transparent, but also allowed other therapists to review and amend goals as necessary:

The client is the one who, ultimately, has ownership, so to say. […] Goals that I as therapist find important, […] I explain to them why these are so important for me, but when I’m unable to convey that to them, then I can say, for example: “I would quite like to try to talk about these in two months again.” (OT3)

Techniques for one-to-one interaction

Participants reported a number of specific techniques, which they applied in one-to-one interaction with clients. Rather than thinking of these as addressing either communication or cognitive impairment, participants drew from this pool of techniques flexibly, to best meet the individual client’s needs:

I find that it is always quite individual, what I then do … when someone has difficulties because of cognition, communication or both. But I would say that one adjusts to the individual [client]. So I wouldn’t generally separate the two. (SLT2)

Many participants talked about how setting achievable intermediate goals “on the way” to the client’s main goal is helpful. This would allow participants to remain focused on the goals as stated by the client, and to refine these jointly with the client through discussion of intermediate goals. Additionally, participants stressed the importance of accommodating clients’ cognitive and emotional needs, for example only speaking when the client is attentive. To support memory deficits, participants reported repeating goals frequently, writing goals down where clients can see them, and linking goals with the therapeutic exercises/activities: “That I repeatedly emphasize the goals, also when I do therapeutic exercises, that I repeatedly explain why I do that or how exactly this will lead to the goal.” (PSY1)

For clients with reduced self-awareness, several participants described a strategy of “experienced activity”. If clients state that they believe they can do a certain activity, but due to their current condition this would probably be unrealistic, participants would let clients try it out in a safe setting. Afterwards, it was important to support clients in reflecting on the outcome, and to relate this back to clients’ impairments and the goal-setting process. Participants stressed that empathy and clarity are essential for facilitating this kind of feedback. “Problematic” key situations during therapy were also often used in a similar way. One participant remarked that clients often experience relief from this type of self-discovery, when they learn to distinguish whether activity limitations relate to personal or external factors, and this may assist clients and professionals in deciding how they will target problematic factors:

Sometimes one must guide them there, that they realize, that it’s necessary to work on something […] maybe it first needs several single sessions, to somehow gently try and show them that they have deficits and to let them become aware of that, so to say. And then one can say, okay, let us formulate the goals once again. (PT1)

The use of adequate language, according to clients’ communication and cognitive skills, was described as essential by all participants. Participants deliberately simplify the way they speak and use words and phrases that relate to clients’ daily life. In addition, participants use different strategies to support communication (). With respect to conversation style, participants described starting the conversation with open questions. If these are too difficult for the client, different topics from various life domains are then offered to “get at” the main problems. If clients require additional support still, more detailed questions are asked, and more structure is provided, for example listing things individually. As the most directive option, participants offer two choices or use closed questions “which can be answered with Yes or No or gestures, respectively, with head-shaking and nodding […], if speech comprehension is sufficient” (PSY2)

Table 3. Strategies to support communication.

To engage in “true” dialog, several participants described different ways of facilitating mutual understanding. For example, a question could be repeated, to check whether the client answers consistently, which would indicate that they have understood. Several participants said they frequently repeat or paraphrase what clients express, to confirm whether they have understood correctly. Similarly, participants would recap and check essential points at the end of a conversation: “One quickly thinks that one has understood, but maybe one is interpreting, […] always be very careful.” (OT5)

Some participants described that identifying the personal motivation “behind” the desired goal can increase the “success rate” of lasting goals. One participant adopted some aspects of nonviolent communication according to Rosenberg [Citation38], whereby she applies probing to discover the person’s motivation behind verbalized goals. This is used to gauge in how far the client’s personal motivation might be met under the present circumstances. If the cognitive and motor skills are insufficient to complete the activity in the intended way, clients may then be supported in finding alternatives to fulfill their personal motivation. This changes the focus from the activity to the personal motivation or meaning “behind” the activity. A case example recounted by OT3 and questions used to elicit the client’s personal motivation behind the goal (OT3, OT5) are given in .

Table 4. Discovering the personal motivation ‘behind’ a goal: case vignette (as recounted by OT3) and suggested questions (OT3, OT5).

Involving relatives

When communication or cognitive impairments are too severe, and with permission of the client, all participants tend to invite relatives (next of kin) to participate in the goal-setting process to identify meaningful goals. At the same time, participants emphasized that goals can often differ between relatives and clients, in which case more weight should be given to clients’ expectations.

Several participants described the importance of informing and educating relatives about goal-setting and the rehabilitation process, to achieve good cooperation between clients, relatives and therapists. In this context, consideration of a “client-system” was mentioned by some participants. This refers to the interaction between the client and their family, which requires a more holistic view. Participants described the importance of relatives agreeing with the client’s goals, when relatives have to participate in, or enable the activities: “it is practically impossible to pursue a goal which the partner didn’t find important or even openly rejected.” (OT4)

In negotiating relatives’ involvement, some participants found it helpful to conduct the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation39] with two statements, mainly when clients were not able to contribute themselves. This means that first, the client’s relatives would be asked to state what they find difficult themselves, with respect to the client’s limitations: “Relatives also need their own space […] then they can also be a better voice [for the patient]” (OT3). Then, relatives are asked to state what they think the client would consider problematic. The remaining appraisal is made with these two statements, for example written in two colors and underlining the agreement. From this, different meaningful goal suggestions can be arrived at, which are then discussed in a goal-conference together with the client.

Several participants described that they would generally hold conversations with relatives in the presence of the client. Sometimes, however, it could be more appropriate to conduct separate conversations first, and bring everyone together at a later point:

Because it could be that the relatives as well as the clients can be better connected with themselves and with their thoughts when they don’t, for example, at the same time wish to protect the other person or be considerate towards the other person. (OT3)

Discussion

This study has documented strategies for involving clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment after stroke in person-centred goal-setting, thereby addressing a current gap in knowledge. Findings from this study are based on accounts from eleven experienced stroke rehabilitation professionals, representing a research approach in which evidence is generated “bottom-up” from real-world clinical practice, using qualitative exploratory methods.

Strategies were grouped according to five themes. These may support clinicians in implementing person-centred goal-setting with stroke clients with communication/cognitive impairment, by specifying overarching tenets (e.g., flexibility) and concrete practices (e.g., allowing a “relaxed” wording of goals). While many of these aspects have been described in the goal-setting literature, some also add novel insights. Moreover, few studies have addressed goal-setting specifically with stroke survivors with communication and/or cognitive impairment. The following discussion therefore incorporates goal-setting literature relating to individuals with stroke or other neurological conditions, and with or without communication/cognitive impairment.

The underlying assumption of the present study was that it is the responsibility of health professionals to enable participation in goal-setting despite communication and/or cognitive impairment, and this is also supported by others [Citation13]. While several previous studies have reported that rehabilitation clients generally wish to participate in goal-setting and treatment-planning [Citation5,Citation12,Citation19,Citation40,Citation41], a number of studies have shown that not all clients want, or feel ready to actively participate; however, this can change during the continuum of rehabilitation and health professionals should be conscious of this [Citation13–15]. This was also reflected in the findings of the present study, whereby participants took the view that clients’ participation in goal-setting was principally possible; and participants talked about remaining flexible and continuing to offer clients opportunities for participation as the rehabilitation process unfolded.

Each person is unique, with different values, preferences, attitudes and circumstances, which are related to their social and physical environment [Citation4], and therefore each person has different needs and desires. The same is true in rehabilitation, and person-centred goal-setting cannot be addressed by “one-size-fits-all” clinical processes [Citation14]. Therefore, different approaches, methods and ways of thinking about person-centred goal-planning are required, to best meet clients’ individual needs, which may also change over time [Citation13–15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation30,Citation32,Citation42–45]. This overarching ethos was strongly represented in our study findings, which emphasize the importance of a flexible, evolving and individual practice, maintaining an open attitude, and leaving one’s own values, preferences, attitudes and notions of “normality” behind to get to know the client [Citation24,Citation46].

Findings from our study offer a number of concrete strategies to realize person-centred goal-setting. Some of these are well established in the literature and will be very familiar to rehabilitation professionals, such as the various communication strategies (using simple language and communication aids, changing slowly between different topics, repeating, confirming understanding, summarizing essential points) [Citation28,Citation47,Citation48], and the point that sufficient time needs to be made available, to achieve mutual understanding and build a trusting client-therapist relationship [Citation20,Citation28,Citation30,Citation47,Citation48]. Additionally, our study suggests that clinicians do not distinguish between goal-setting strategies for clients with either communication or cognitive impairments, because these often overlap and each client has different needs. Instead, clinicians draw from a repertoire of strategies to best meet the individual client’s needs. Also, rather than uncovering any new and original strategies from participants’ practice, our study findings emphasize that it is the conscientious and deliberate application of strategies that are generally known, combined with the ambition to involve clients with communication/cognitive impairments, which distinguishes the person-centred goal-setting practices in this group of experts from more clinician-led, directive goal-setting.

Some of the strategies described in the current study may nevertheless be regarded as less common, such as “experienced activity”, which was described as one way to address reduced self-awareness. Judd and Wilson similarly described “reality testing” as an effective strategy to increase awareness of post-injury changes and limitations [Citation49]. Further, experiential, observational, audio and video feedback, as well as constructive feedback and structured experiences were described to gain self-awareness during rehabilitation after brain injury [Citation20,Citation50]. Important to this is, as the participants of the current study described, that clients are supported with empathy and clarity when reflecting on the performance of the activity.

The experiences of participants in this study suggested that identifying personal motivation behind the desired goal can increase the “success rate” of lasting goals. This resonates with authors who suggest considering social identity considerations or high-order life goals [Citation17,Citation40]. Playford described that “it is the identifying why the goal is important that matters” [Citation4], implying that professionals should consider the roles of clients, individuals’ values and preferences, their priorities in life, “personal strivings”, subjective well-being, and desired sense of self [Citation4,Citation17,Citation40,Citation44,Citation51]. Van de Velde et al. found that formal assessment is not useful for discovering meaning in life, but spending time together, using informal ways of information gathering and active listening, was shown to be effective [Citation26]. In the same vein, Martin et al. concluded from their findings that rehabilitation services should “consider broadening their focus from functional status rehabilitation to include social identity considerations” [Citation40].

Study participants also discussed the use of SMART goals. In contrast to the pervasive advice to use SMART goals within the rehabilitation literature, there is also an emerging body of literature which questions the widespread use of the SMART approach [Citation14,Citation24,Citation30,Citation32,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45]. This is supported by our findings, as participants described a “relaxed” wording of goals, which refers to rejecting a formulaic application of all SMART criteria. Similarly, in the study by Hunt et al. therapists who embraced client-determined goals did not apply the SMART approach in a strict manner [Citation24]. The acronym SMART is usually used in rehabilitation as a standard in formulating goals [Citation44,Citation45]. But one significant limitation, among others, is that SMART was designed for goal-setting within business and not for clinical practice, which means that experiences of impaired people were not considered in its development [Citation43]. This is apparent when reviewing the SMART approach with respect to person-centredness, as authors often acknowledge that SMART goals may not meet the needs of rehabilitation clients, and can often be more professional- than client-centred [Citation9,Citation23,Citation24,Citation32].

Our study clearly demonstrates participants’ personal commitment and motivation to enable client autonomy, and to support clients in making their own decisions within rehabilitation and life in general. Hammel, who describes autonomy as the power and right of self-government and self-determination [Citation46], asserts that clinicians and clients often have different perceptions of independence. Health professionals tend to interpret independence as performing self-care activities without physical assistance, and they rarely attempt to explore the client’s perspective of independence [Citation46]. In contrast, decisional autonomy can often be much more important for clients than physical independence in self-care activities [Citation46,Citation52]. Autonomy therefore refers not to absolute control or domination, but to an ability to influence, direct, choose and manage one’s life as situations and roles demand and personal preferences dictate [Citation46]. This is a particularly salient point in the context of stroke clients with communication/cognitive impairment, who will often also present with significant physical impairment and functional limitations. Accordingly, participants in the present study discussed a number of strategies to enable autonomy, such as encouraging clients to actively participate in goal-setting, stressing clients’ ownership of their goals, and providing information and education. The latter in particular is widely supported in the literature, which shows that one of the most commonly reported barriers of shared decision-making in goal-setting is lack of knowledge [Citation4,Citation12,Citation13,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation53,Citation54]. The provision of information equates to a sharing of power, thereby empowering clients to maximize their independence and fulfilling health professionals’ ethical responsibility to promote self-determination [Citation13,Citation41,Citation55–57].

While interviewees asserted that it was principally possible to involve clients with communication/cognitive impairment in goal-setting, it was also acknowledged that at times this may not be the case and decisions may need to be supported through involving clients’ relatives. In the literature, family involvement in goal-setting is described with contrasting positive and negative effects [Citation4,Citation13,Citation18,Citation29,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59]. Studies have found that relatives were influenced by their own feelings and preferences and were not always able to anticipate the response of the client [Citation18,Citation29,Citation59], and direct comparison has shown that goals formulated by people with aphasia and their relatives differ [Citation29,Citation56]. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that communication and cognitive impairment can affect the whole family, and therefore relatives should, with permission of the client, be involved in the rehabilitation process [Citation60,Citation61]. Accordingly, participants in our study described working with the “client-system”. Although the client was thought to have the “final say”, it was considered important that relatives agree with or shape the client’s goals, especially when they are required to participate in or enable activities. Furthermore, participants emphasized making time to listen to relatives’ concerns; and to inform and educate relatives in the same way they would inform and educate the client. As in previous studies [Citation18,Citation60], this was considered important to achieve good cooperation between clients, relatives and professionals.

In summary, this study has documented aspects and strategies of goal-setting with clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment and hence provided an overview of the topic in relation to clinical practice. Strategies have been described from clinical practice and are well-supported by the wider literature. These findings could be useful for clinicians who wish to familiarize themselves with the application of person-centred goal-setting with clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment, or who wish to compare their own practice to that of peers.

Strengths, limitations and further directions

To our knowledge, this has been the first study to explore and document person-centred goal-setting for stroke clients with communication/cognitive impairment from the central European region. Strengths of the study include data collection through individual interviews, generating more in-depth data than questionnaires, and strategies to enhance trustworthiness (member-checking, peer review, researcher reflexivity). It is acknowledged that the sample size was limited by time and resources available, with more representation from some professional groups than others. Although comparison of person-centred practice between professional groups was not the focus of this study, further research could aim to recruit more widely across rehabilitation professions and explore possible differences and similarities in approaches and opinions. Data saturation was not formally assessed, and it is possible that further data collection would lead to accounts of additional strategies. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that data from this study are more representative of subacute inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation practice, than acute rehabilitation.

Social desirability bias is acknowledged as a possible weakness, as interviewees could have responded in a socially desired (person-centred) manner. Without direct observation of client-professional interactions it cannot be ascertained whether participants’ accounts match their actual practice, and whether these described strategies are in fact successful. Additionally, the method only allows the exploration of strategies which interviewees are aware of. These limitations could be addressed, for example, through triangulation with non-participant observations of goal-setting sessions.

Due to the small sample size and methodological limitations in this study, further research is warranted. Although generalization of the study results is limited, this is also not the intention in qualitative research such as this. The results offer useful data for transferability and provide a basis for future research, which could incorporate non-participant observations of goal-setting sessions, capture clients’ experiences and perspectives, and focus on specific parts of the rehabilitation pathway (e.g., acute rehabilitation) for a more in-depth exploration of strategies according to rehabilitation phases.

Conclusion

Communication and cognitive disorders are common after stroke and pose a considerable challenge to person-centred goal-setting in neurological rehabilitation. Rehabilitation professionals require a high level of skill and expertise to use different approaches and methods to best meet the individual needs of their clients. This study has generated accounts from a group of experienced stroke rehabilitation professionals, illustrating a repertoire of practice-based goal-setting strategies. Health professionals may draw on these findings to enhance and facilitate their goal-setting practice with stroke clients with communication and/or cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120:439–448.

- Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Côté R, et al. Activity, participation, and quality of life 6 months poststroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1035–1042.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: short version. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Playford ED. Goal setting as shared decision making. In: Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, editors. Rehabilitation goal setting: theory, practice and evidence. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. p. 89–104. (Rehabilitation science in practice series).

- Cott CA. Client-centred rehabilitation: client perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1411–1422.

- Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, et al. Person-centredness: conceptual and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1555–1565.

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Standards of practice for occupational therapy [Official document]. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69:1–6.

- Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guideline for stroke. 5th ed. Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, editor. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2016.

- Playford ED, Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, et al. Areas of consensus and controversy about goal setting in rehabilitation: a conference report. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:334–344.

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy. WCPT guideline for standards of physical therapy practice [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://www.wcpt.org/guidelines/standards

- Levack WMM, Weatherall M, Hay-Smith EJC, et al. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD009727.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings : a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:65–75.

- Berg K, Askim T, Balandin S, et al. Experiences of participation in goal setting for people with stroke-induced aphasia in Norway. A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1122–1130.

- Brown M, Levack WMM, McPherson KM, et al. Survival, momentum, and things that make me ‘me’: patients’ perceptions of goal setting after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1020–1026.

- Laver K, Rehab MC, Halbert J, et al. Patient readiness and ability to set recovery goals during the first 6 months after stroke. J Allied Health. 2010;39:149–154.

- Ekdahl AW, Andersson L, Friedrichsen M. ‘They do what they think is the best for me.’ Frail elderly patients’ preferences for participation in their care during hospitalization. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:233–240.

- Rosewilliam S, Pandyan AD, Roskell CA. Goal setting in stroke rehabilitation: theory, practice and future directions. In: Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, editors. Rehabilitation goal setting: theory, practice and evidence. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. p. 345–370.

- Berg K, Rise MB, Balandin S, et al. Speech pathologists’ experience of involving people with stroke-induced aphasia in clinical decision making during rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:870–878.

- Worrall L, Sherratt S, Rogers P, et al. What people with aphasia want: their goals according to the ICF. Aphasiology. 2011;25:309–322.

- Prescott S, Fleming J, Doig E. Rehabilitation goal setting with community dwelling adults with acquired brain injury: a theoretical framework derived from clinicians’ reflections on practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;0:1–12.

- Rosewilliam S, Roskell CA, Pandyan A. A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:501–514.

- Rosewilliam S, Sintler C, Pandyan AD, et al. Is the practice of goal-setting for patients in acute stroke care patient-centred and what factors influence this? A qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:508–519.

- Levack WMM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: how clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:206–213.

- Hunt AW, Le Dorze G, Trentham B, et al. Elucidating a goal-setting continuum in brain injury rehabilitation. Qual Health Res. 2015;25:1044–1055.

- Plant SE, Tyson SF, Kirk S, et al. What are the barriers and facilitators to goal-setting during rehabilitation for stroke and other acquired brain injuries? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:921–930.

- Van de Velde D, Devisch I, De Vriendt P. The client-centred approach as experienced by male neurological rehabilitation clients in occupational therapy. A qualitative study based on a grounded theory tradition. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1567–1577.

- Leach E, Cornwell P, Fleming J, et al. Patient centered goal-setting in a subacute rehabilitation setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:159–172.

- Hunt AW, Le Dorze G, Polatajko H, et al. Communication during goal-setting in brain injury rehabilitation: what helps and what hinders? Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78:488–498.

- Haley K, Womack J, Helm-Estabrooks N, et al. Supporting autonomy for people with aphasia: use of the Life Interests and Values (LIV) cards. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013;20:22–35.

- Hersh D, Worrall L, Howe T, et al. SMARTER goal setting in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology. 2012;26:220–233.

- Murphy J, Boa S. Using the WHO-ICF with talking mats to enable adults with long-term communication difficulties to participate in goal setting. Augment Altern Commun. 2012;28:52–60.

- Parsons JGM, Plant SE, Slark J, et al. How active are patients in setting goals during rehabilitation after stroke? A qualitative study of clinician perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:309–316.

- Ritschl V, Stamm T. Stichprobenverfahren und Stichprobengröße. In: Ritschl V, Weigl R, Stamm T, editors. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten und Schreiben. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. p. 61–65.

- Lamnek S. Qualitative sozialforschung. 4th ed. Weinheim: Beltz; 2005. p. 808.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2013. p. 449.

- Barnes MP, Ward AB. Textbook of rehabilitation medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 391.

- Rosenberg MB. Gewaltfreie Kommunikation: Eine Sprache des Lebens. 12th ed. Paderborn: Junfermann Verlag; 2016. p. 224.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. COPM canadian occupational performance measure fourth edition. 2nd ed. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner Verlag GmbH; 2011. p. 68.

- Martin R, Levack WMM, Sinnott KA. Life goals and social identity in people with severe acquired brain injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:1234–1241.

- Sherratt S, Worrall L, Hersh D, et al. Goals and goal setting for people with aphasia, their family members and clinicians. In: Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, editors. Rehabilitation goal setting: theory, practice and evidence. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. p. 325–343.

- Hersh D, Sherratt S, Howe T, et al. An analysis of the “goal” in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology. 2012;26:971–984.

- McPherson KM, Kayes NM, Kersten P. MEANING as a smarter approach to goals in rehabilitation. In: Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, editors. Rehabilitation goal setting: theory, practice and evidence. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. p. 105–119.

- Siegert RJ, Taylor WJ. Theoretical aspects of goal-setting and motivation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1–8.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:291–295.

- Hammell KW. Perspectives on disability & rehabilitation: contesting assumptions; challenging practice. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier; 2006. p. 258.

- Tesak J. Aphasie - Sprachstörungen nach Schlaganfall oder Schädel-Hirn-Trauma: Ein Ratgeber für Angehörige und medizinische Fachberufe. 4., überar. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner; 2014. p. 72

- Wehmeyer M, Grötzbach H. Zusammenarbeit mit Patienten und Angehörigen. In: Thiel MM, Frauer C, editors. Aphasie: Wege aus dem Sprachdschungel. 5th ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 135–157. (Praxiswissen Logopädie).

- Judd D, Wilson SL. Psychotherapy with brain injury survivors: an investigation of the challenges encountered by clinicians and their modifications to therapeutic practice. Brain Inj. 2005;19:437–449.

- Medley AR, Powell T. Motivational Interviewing to promote self-awareness and engagement in rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a conceptual review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20:481–508.

- Bright F, Kayes NM, McCann CM, et al. Hope in people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2013;27:41–58.

- Cardol M, De Jong BA, Ward CD. On autonomy and participation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:975–976.

- Rose T, Worrall LE, McKenna KT, et al. Do people with aphasia receive written stroke and aphasia information? Aphasiology. 2009;23:364–392.

- Rose T, Worrall L, Hickson L, et al. Do people with aphasia want written stroke and aphasia information? A verbal survey exploring preferences for when and how to provide stroke and aphasia information. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17:79–98.

- Levack WMM, Weatherall M, Hay-smith EJC, et al. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit in adult rehabilitation: summary of a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52:400–416.

- Pettit LK, Tonsing KM, Dada S. The perspectives of adults with aphasia and their team members regarding the importance of nine life areas for rehabilitation: a pilot investigation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2017;24:99–106.

- Suleman S, Hopper T. Decision-making capacity and aphasia: speech-language pathologists’ perspectives. Aphasiology. 2016;30:381–395.

- Prescott S, Fleming J, Doig E. Goal setting approaches and principles used in rehabilitation for people with acquired brain injury: a systematic scoping review. Brain Inj. 2015;29:1515–1529.

- Levack WMM, Siegert RJ, Dean SG, et al. Goal planning for adults with acquired brain injury: how clinicians talk about involving family. Brain Inj. 2009;23:192–202.

- Howe T, Davidson B, Worrall L, et al. ‘You needed to rehab … families as well’: family members’ own goals for aphasia rehabilitation. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012;47:511–521.

- Wallace SJ, Worrall L, Rose T, et al. Which outcomes are most important to people with aphasia and their families? An international nominal group technique study framed within the ICF. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1364–1379.