Abstract

Purpose: Participation in activities of everyday life is seen as main goal of rehabilitation after a stroke and return to work is an important factor to consider for the substantial number of persons having a stroke at working age. The current study aims to investigate whether returning to work would predict self-perceived participation and autonomy in everyday life after a stroke, from a long-term perspective.

Materials and methods: Persons with first-ever stroke at age 18–63 years in 2009–2010, Gothenburg, were included. As 5-year follow-up, the Impact on Participation and Autonomy questionnaire was sent out, investigating self-perceived participation/autonomy in five levels, and work status was investigated from national sick-absence registers. Prediction of work on participation/autonomy was investigated with logistic regression.

Results: A total of 109 participants (49%) responded to the questionnaire. The majority (69–94%) perceived very good participation/autonomy in all domains and 59% were working 5 years after stroke. Working was a significant predictor of high participation/autonomy in all domains of the questionnaire.

Conclusions: Being able to return to work after a stroke seems to be important for self-perceived participation/autonomy. This emphasizes the importance of work-oriented information and rehabilitation after a stroke at working age.

The current study shows that the majority report high self-perceived participation and autonomy in everyday life and 59% are working 5 years after a stroke in working age.

To work 5 years after a stroke was a significant predictor for self-perceived participation and autonomy in everyday life.

Since stroke is becoming more common among working age persons and work seem important for perceived participation and autonomy, to optimize the return to work by for instance work-oriented information and vocational rehabilitation is important.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common diseases in the world [Citation1]. It is perceived as a disease of the elderly, but a substantial number of individuals affected by stroke are of working age [Citation2,Citation3]. The consequences of a stroke include not only physical impairment, but also cognitive and psychological symptoms [Citation4,Citation5].

The ability to participate in meaningful activities is seen as important for one’s well-being and quality of life after a stroke and could be seen as main goal of rehabilitation [Citation6]. In the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), participation is defined as involvement in a life situation [Citation7]. However, other factors may also influence level of participation, and a person that is involved in a life situation does not automatically experience higher participation [Citation8]. Therefore, participation may be seen as the intersection of what a person can do, wants to do, has the opportunity to do, and is not prevented from doing by the context in which the person lives and seeks to participate [Citation9]. Autonomy means self-rule and implies that people have the right to make their own choices and decide how, when, and where to participate in activities [Citation10]. Thus, the concepts of participation and autonomy are strongly connected. Higher age, more severe stroke, dependency in activities of daily life, presence of comorbidities, decreased extremity function, and psychological and cognitive symptoms have been presented as risk factors for lower participation after stroke [Citation11–16].

Work is one of the domains included in the concept of participation. The rate of return to work (RTW) after stroke has varied from ∼20% to 75% between different studies and countries, as presented in a review article [Citation17]. RTW is important for quality of life [Citation18], and those who do not work have a higher risk of not being satisfied with life after a stroke [Citation19]. As a substantial proportion of the persons having stroke are of working age, RTW is also economically important for society. The indirect costs of productivity losses due to premature death, early retirement, and sick leave constituted 21% of the total costs of stroke in previous research [Citation20]. However, whether RTW is a significant factor for experiencing participation in everyday life after a stroke is not yet clear.

The current study aims to investigate whether returning to work would predict self-perceived participation and autonomy in everyday life after a stroke, from a long-term perspective.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study employed a retrospective cohort design. The STROBE statement, which is a guideline for reporting observational studies, was followed when applicable. Baseline data were collected from medical records. The follow-up consisted of two parts: a questionnaire on perceived participation and autonomy, and data on work status from the Social Insurance Agency. The questionnaire was sent out approximately 5 years after the participant’s stroke, with a maximum of two reminders by mail if no response, and data were collected from the Social Insurance Agency up to 5 years after their stroke.

Participants

The participants were from the extended Stroke Arm Longitudinal Study at the University of Gothenburg (SALGOT-extended) [Citation21–23] and were patients with first ever stroke according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes I60 subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), I61 intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), or I63 ischemic stroke (IS) at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sahlgrenska, Gothenburg, Sweden between 4 February 2009 and 2 December 2010. Additional inclusion criteria were the following: living within the geographic catchment area (within 35 km of the hospital); and age 18–63 years at the time of the stroke.

Variables

The baseline data included age, sex, stroke type, and comorbidity according to the Charlson comorbidity index [Citation24]. A Charlson comorbidity score of 0–1 points indicates no comorbidity, 2–3 points mild comorbidity, 4 points moderate comorbidity, and >5 points severe comorbidity [Citation25]. In addition, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS; 0–46 points, lower score is better) assessed stroke severity at the time of admission to the hospital. Patients in which the NIHSS was not assessed, such as SAH patients and patients with severely decreased consciousness, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; 3–15 points, higher score is better) was used. A GCS score of 13–15 points is considered mild, 9–12 points moderate, and 3–8 points severe. The modified Rankin Scale (mRS; 0–5 points, lower score is better) was used to assess functional dependency at discharge from the hospital. The mRS was dichotomized into two groups (due to sample size) representing functional independency at discharge (0–2 points) and functional dependency (3–5 points) [Citation26].

The follow-up questionnaire sent out to all persons eligible for participation included the English version of the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA-E) questionnaire [Citation27] translated into Swedish. The IPA-E consists of 32 items that can be divided into five domains: autonomy indoors, family role, autonomy outdoors, social life and relationships, and work and education. All items have five possible answers: very good (i.e., highest perceived participation and autonomy), good, fair, poor, or very poor. In addition to these five domains, the IPA-E examines whether the participants experience problems in nine different areas (mobility, self-care, activities in and around the house, looking after your money, leisure, social life and relationships, helping and supporting other people, paid and voluntary work, and education and training) with three possible answers: no problems, minor problems, or major problems. The IPA-E manual was used to handle and interpret the results [Citation27].

The Social Insurance Agency, which is a state authority available to all with permanent residence in Sweden, provided data on sickness benefits (sick leave) and sickness compensation (early retirement) 1 year prior to the stroke and up to 6 years after the stroke. Working was defined as no registration for sickness benefit or sickness compensation full or part time, not being 65 years old (old-age retirement in Sweden), and not being deceased at the end of follow-up. In Sweden, the employer provides sick pay for the first 2 weeks of absence. The Social Insurance Agency then provides sickness benefit or sickness compensation, when a RTW is unlikely due to sickness. However, it is still possible for a person with sickness compensation to RTW. The Social Insurance Agency follow a step-by-step rehabilitation model to evaluate a person’s capacity to work, with more stringent criteria the longer a person has been on sick leave. In the current study, the participants receiving sickness compensation prior to the stroke were included in the non-working group. The mortality register at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare provided dates of death within the follow-up period.

Statistical methods

IBM SPSS 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to store and analyze the data. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 and two-tailed tests were used. Fisher’s exact test and the Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare differences between groups (for instance drop outs versus responders, RTW versus no-RTW).

To assess possible prediction of work status, logistic regression was used in the different domains of participation and autonomy. Separate regression models were created for each participation and autonomy domain. In the regression analyses, the answers in the domains of the IPA-E were dichotomized into two groups: “very good,” representing high participation and autonomy, and “good-very poor,” representing limited participation and autonomy, creating a binary dependent variable. Work status was set as the independent variable. Work status was adjusted for age, functional dependency at discharge (mRS), and sex in the regression analyses for the domains in which the inclusion of more than one independent variable were allowed considering the limited group size to avoid overfit [Citation28]. If all of the adjustment variables were not allowed, age was chosen first and functional dependency second, based on clinical reasoning. The Nagelkerke R2 (variance in the outcome explained by the model) was calculated for the regression models, as well as the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The original SALGOT-study, the follow-up questionnaire, and the follow-up with the Social Insurance Agency were all approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Gothenburg (Dnr: 225–08, T801-10, Dnr: 400–13 and Dnr: T830–15). The participants received information about the research and that it was voluntary to participate at the time of the follow-up questionnaire. According to the Swedish Data Inspection Board, data that are handled within the frame of national quality registers is an exception from the general rule of informed consent because it allows improvement of the quality of care and treatment that is of general interest.

Results

Characteristics

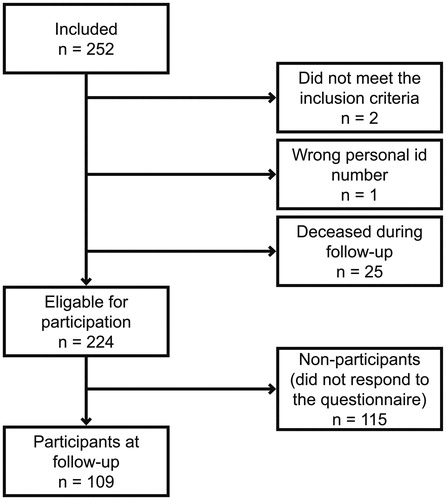

A total of 109 participants (49%) out of the 224 eligible, responded to the follow-up questionnaire (). The participants were significantly older than the non-participants (U = 5294.5, p = 0.045) according to Mann–Whitney U test, but did not differ significantly in terms of sex (p = 0.677), stroke type (p 0.712), or functional dependency (mRS) at discharge (p = 0.894) according to Fischer’s exact test.

As seen in , the majority of the participants were male. IS was the most common stroke type, followed by ICH and SAH. The NIHSS scores and GCS scores indicated that the majority of participants suffered from a mild stroke.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population.

Participation and autonomy

A total of 21 participants did not respond to the questions in the work and education domain; therefore, this domain was excluded from further analysis. In all of the domains in the analyses, the majority reported very good perceived participation and autonomy 5 years after stroke, as could be seen in . Similarly, few participants reported problems in any of the nine areas concerning problems experienced on the IPA-E. The highest rate of very good participation and autonomy was reported in autonomy indoors (84%) and the lowest rate in social life and relationships (55%). Furthermore, the fewest problems were reported in the helping and supporting other people area (92% did not experience problems), and the most problems were reported in social life and relationships (only 62% did not experience problems).

Table 2. Comparison of participation and autonomy between working and non-working groups, using Mann–Whitney U test.

Work status

Of the 94 participants that were not on early retirement prior to the stroke, 68.1% did RTW and were still working at the end of follow-up. Their RTW continued until almost 3 years post-stroke. This yielded a working group of 64 participants (59%) and a non-working group of 45 participants (41%). In the non-working group, eight participants were on early retirement since before the stroke, 11 received early retirement after the stroke, and 26 were old-age retired at the end of follow-up.

Impact of work on participation and autonomy

The working group reported higher perceived participation and autonomy in all domains of the IPA-E compared to the non-working group (). In addition, the participants that were working reported significantly less experience with problems in all areas. Furthermore, working was a significant predictor of high participation and autonomy in all IPA-E domains () with OR 6.29 for autonomy indoors, 8.17 for family role, 4.91 for autonomy outdoors, and 5.53 for social life and relationships.

Table 3. Logistic regression with work as independent factor and each domain in IPA-E as dependent factors.

Discussion

The participants in the current study experienced high participation and autonomy 5 years after stroke, and a majority were working at the end of follow-up. Workers reported significantly higher perceived participation and autonomy in everyday life than non-workers. Working was also a significant predictor of high participation and autonomy 5 years after stroke. The importance of RTW highlights the importance of work-oriented information and rehabilitation in the health care system.

Generally, the participants perceived a high level of participation and autonomy. Two previous studies conducted in Iran and the Netherlands using the IPA to follow-up after stroke reported poorer perceived participation and autonomy than in the current study in all domains [Citation29,Citation30]. This difference may have to do with different views on disability and different healthcare systems. Environmental factors, such as social attitudes, system services, and policies, seem to influence participation in the community [Citation31]. In addition, shorter time to follow-up in the previous studies could also explain the lower level of participation, as a change in participation over years after a stroke has been shown [Citation32]. The current study measured self-perceived participation and autonomy, which may differ from participation that is measured objectively. For example, previous research showed that experienced participation is associated with objective participation in vocational activities, but not leisure and social activities, after a stroke [Citation33].

The social life and relationships domain in the current study had the lowest frequency of high participation and autonomy. One reason for this finding could be that a stroke survivor and his/her partner experience being more defined by roles as the giver or recipient of care in their relationships after a stroke at a younger age [Citation34]. Autonomy indoors had the highest rate of high participation and autonomy, and this domain mainly focuses on mobility and activities of daily living. Other domains may be more complex and, for example, demand higher cognitive function. The majority of participants in the current study had a mild stroke, with which cognitive impairments and psychological problems often occur [Citation35]. Therefore, rehabilitation efforts focusing on the risk of more limited participation and autonomy could be important after a stroke.

The RTW rate was high in the current study compared to previous studies [Citation17]. This is concordant with the high participation and autonomy in the current study, and the reasons for diverging RTW rates between studies could be similar to the reasons for diverging participation and autonomy (i.e., different healthcare systems, social attitudes, and study methods). As an example, the current study has a follow-up time of 5 years, which is longer than most previous research [Citation36]. The use of a longer follow-up period allows for a greater number of people to RTW.

There is a connection between work status and level of perceived participation and autonomy in everyday activities after a stroke, and working seems to be an important predictor of perceived participation and autonomy. Concordant with the current results, RTW after a stroke is significantly related to well-being in many areas of life [Citation37]. Persons that RTW after a stroke reported higher levels of daily activities, better quality of life, and were less avoidant in their coping strategies compared to those who did not RTW [Citation38]. Whether work status is important for perceived participation and autonomy or if people experiencing a high participation and autonomy are more likely to RTW may be a topic for further research. The healthy worker effect has to be considered, as a working population has better health than the general population, and it is difficult to establish the causation [Citation39]. Working may not change the actual frequency of autonomy indoors activities. However, work likely contributes to a greater experience of participation and autonomy due to changed focus and perspectives on life. Work can be suggested to be important for a sense of identity and belonging in society and a social context, besides the financial benefits. These terms are all closely associated with participation and autonomy. The fact that work status seems to have an effect on several aspects of a person’s life after a stroke emphasizes the importance of vocational rehabilitation.

The confidence intervals in the regression analyses were wide; thus, the true estimate of prediction is uncertain. Acceptable accuracy was observed according to the ROC curves and the variance in the outcome explained by the model varied between 16% and 35%. This indicates that working is not the only important predictor of participation and autonomy. Therefore, it may be important in future research to include both work status and other factors in a predictor analysis of participation and autonomy, but this may require a larger study population. Other factors could include the presence of psychological symptoms or cognitive deficits, which have been shown to be important previously [Citation11–14], as well as socioeconomic factors and work-related concerns from the employer of employee.

Limitations

The way in which work status was operationalized within the current study may have been a limitation. Working was defined as not being registered for sickness benefit or sickness compensation (full time or part time) at the Social Insurance Agency and not being old-age retired or deceased. However, there are reasons other than working for non-registration. The current study does not consider, for example, unemployment or persons receiving assistance from Social Services in Sweden. Yet, the strong association between working and participation and autonomy in the current study strengthens the assumption that the persons defined as working actually are working. These differences in social insurance systems alongside with differences in healthcare systems between countries have an impact on the generalizability of the results. The use of self-reported data entails a risk for information bias. However, participation and autonomy is difficult to assess objectively without self-reported data, why a questionnaire still was used.

For the regression analyses, the dependent variables were dichotomized and, due to the distribution of answers in the IPA-E, the cutoff had to be between “very good” and “good” participation and autonomy, creating the groups “high participation and autonomy” and “limited participation and autonomy.” Other cutoffs could have been used and would have had an impact on the results.

The participants were predominately male, the majority had a mild stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke (ICH and SAH) was relatively more common than in the general stroke population. The higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke and stroke among males when investigating stroke at a younger age has been reported previously [Citation40]. The response frequency in the current study is just below 50%, which is in line with other questionnaire surveys in Sweden [Citation41]. Although the baseline characteristics of the participants and non-participants differed significantly only in regards to age, there is a risk limited generalizability due to differences during follow-up; for example, the non-participants may experience lower participation and autonomy. Another limiting factor for the generalizability is the lack of background information about for instance socioeconomic status and work related factors (such as content of work, attitudes at the work place, working hours, and configuration of workplace) of the participants. The relatively small sample size also limits the current study. Furthermore, the work and education domain on the IPA-E had a substantial dropout as in previous study [Citation42]. However, the domain is not particularly relevant for making comparisons to work status in the current study and was excluded from the analyses.

Conclusions

High participation and autonomy in everyday life was experienced 5 years after a stroke at working age. Returning to work after a stroke is important for the self-perceived participation and autonomy. Changed work status affects several aspects of a person’s life and, therefore, it is important that the information and rehabilitation efforts after a stroke at working age be work-oriented.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. According to the Swedish regulation http://www.epn.se/en/start/regulations/ the permission to use data is only for what has been applied for and then approved by the Ethical board. Data are available from the authors (contact Professor Katharina S. Sunnerhagen, email: [email protected]) upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Krishnamurthi RV, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global and regional burden of first-ever ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e259–e281.

- Wolf TJ, Baum C, Connor LT. Changing face of stroke: implications for occupational therapy practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63:621–625.

- Rosengren A, Giang KW, Lappas G, et al. Twenty-four-year trends in the incidence of ischemic stroke in Sweden from 1987 to 2010. Stroke. 2013;44:2388–2393.

- Broomfield NM, Quinn TJ, Abdul-Rahim AH, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms post-stroke/TIA: prevalence and associations in cross-sectional data from a regional stroke registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:198.

- Sun JH, Tan L, Yu JT. Post-stroke cognitive impairment: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:80.

- Desrosiers J. Muriel Driver Memorial Lecture. Participation and occupation. Can J Occup Ther. 2005;72:195–204.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). 2001 [cited 2017 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

- Bergström AL, Von Koch L, Andersson M, et al. Participation in everyday life and life satisfaction in persons with stroke and their caregivers 3-6 months after onset. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:508–515.

- Mallinson T, Hammel J. Measurement of participation: intersecting person, task, and environment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:S29–S33.

- Cardol M, de Haan RJ, van den Bos GA, et al. The development of a handicap assessment questionnaire: the Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA). Clin Rehabil. 1999;13:411–419.

- Gall SL, Dewey HM, Sturm JW, et al. Handicap 5 years after stroke in the north east Melbourne stroke incidence study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:123–130.

- Feigin VL, Barker-Collo S, Parag V, et al. Auckland Stroke Outcomes Study: Part 1: gender, stroke types, ethnicity, and functional outcomes 5 years poststroke. Neurology. 2010;75:1597–1607.

- Liman TG, Heuschmann PU, Endres M, et al. Impact of low mini-mental status on health outcome up to 5 years after stroke: the Erlangen Stroke Project. J Neurol. 2012;259:1125–1130.

- Patel MD, Coshall C, Rudd AG, et al. Cognitive impairment after stroke: clinical determinants and its associations with long-term stroke outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:700–706.

- Desrosiers J, Noreau L, Rochette A, et al. Predictors of long-term participation after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:221–230.

- Gadidi V, Katz-Leurer M, Carmeli E, et al. Long-term outcome poststroke: predictors of activity limitation and participation restriction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1802–1808.

- Treger I, Shames J, Giaquinto S, et al. Return to work in stroke patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1397–1403.

- Westerlind E, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Return to work after a stroke in working age persons; a six-year follow up. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169759.

- Roding J, Glader EL, Malm J, et al. Life satisfaction in younger individuals after stroke: different predisposing factors among men and women. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:155–161.

- Ghatnekar O, Persson U, Asplund K, et al. Costs for stroke in Sweden 2009 and developments since 1997. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30:203–209.

- Persson HC, Parziali M, Danielsson A, et al. Outcome and upper extremity function within 72 hours after first occasion of stroke in an unselected population at a stroke unit. A part of the SALGOT study. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:162.

- Vikholmen K, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Stroke treated at a neurosurgical ward: a cohort study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132:329–336.

- Wesali S, Persson HC, Cederin B, et al. Improved survival after non-traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage with structured care pathways and modern intensive care. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;138:52–58.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

- Chang WH, Sohn MK, Lee J, et al. Return to work after stroke: the KOSCO Study. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:273–279.

- Cioncoloni D, Piu P, Tassi R, et al. Relationship between the modified Rankin Scale and the Barthel Index in the process of functional recovery after stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;30:315–322.

- Kersten P. Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA) Manual to the English version: IPA. 2007 [cited 2017 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/INT-IPA-Manual.pdf

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379.

- Fallahpour M, Tham K, Joghataei MT, et al. Perceived participation and autonomy: aspects of functioning and contextual factors predicting participation after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:388–397.

- Cardol M, de Jong BA, van den Bos GAM, et al. Beyond disability: perceived participation in people with a chronic disabling condition. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:27–35.

- Wong AWK, Ng S, Dashner J, et al. Relationships between environmental factors and participation in adults with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional multi-center study. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:2633–2645.

- Ytterberg C, Dybãck M, Bergstrãm A, et al. Perceived impact of stroke six years after onset, and changes in impact between one and six years. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:637–643.

- Blomer AM, van Mierlo ML, Visser-Meily JM, et al. Does the frequency of participation change after stroke and is this change associated with the subjective experience of participation? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:456–463.

- Quinn K, Murray CD, Malone C. The experience of couples when one partner has a stroke at a young age: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1670–1678.

- Tellier M, Rochette A. Falling through the cracks: a literature review to understand the reality of mild stroke survivors. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16:454–462.

- Edwards JD, Kapoor A, Linkewich E, et al. Return to work after young stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2017;13:243-256.

- Vestling M, Tufvesson B, Iwarsson S. Indicators for return to work after stroke and the importance of work for subjective well-being and life satisfaction. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35:127–131.

- Arwert HJ, Schults M, Meesters JJL, et al. Return to work 2–5 years after stroke: a cross sectional study in a hospital-based population. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:239–246.

- Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med. 1999;49:225–229.

- Jacobs BS, Boden-Albala B, Lin IF, et al. Stroke in the young in the northern Manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 2002;33:2789–2793.

- SOM-INSTITUTET. SOM-undersökningarna 2016 – En metodöversikt (SOM-investigations 2016 – A methodological overview). 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 21]. Available from: https://som.gu.se/digitalAssets/1649/1649122_som-unders–kningarna-2017—en-metodrapport.pdf

- Fallahpour M, Jonsson H, Joghataei MT, et al. Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA): PSYChometric evaluation of the Persian version to use for persons with stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 2011;18:59–71.