Abstract

Introduction

Spinal cord injury may seriously affect sexual health and sexuality, which can lead to lower self-esteem, social isolation, lower quality of life, and an increased risk of depression. Nurses play an extensive role in providing patient education. However, a gap between the patients’ need for information and the lack of information provided by nurses still exists. Therefore, knowledge about barriers and facilitators regarding discussing patient sexuality is necessary.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 25 nurses working in Spinal Cord Injury rehabilitation in one clinic in the Netherlands. The following themes were discussed during the interviews: (1) attitude, (2) social factors, (3) affect, (4) habits and (5) facilitating conditions.

Results

Addressing patient sexuality was difficult due to the nurses’ attitude and their environment. Sexuality was considered important but respondents were reserved to discuss the topic due to taboo, lack of knowledge, and common preconceptions. Participants expressed the need for education, a clear job description, time and privacy.

Conclusion

Nurses consider discussing patient sexuality as important but are hindered due to multiple factors. Organizational efforts targeted at knowledge expansion are needed to break the taboo and remove preconceptions. Nurses should provide opportunities to discuss the subject to intercept sexuality-related problems.

The specific tasks of each profession within the multidisciplinary team regarding patient sexuality should be discussed, agreed upon and protocolized.

Adding a sexologist in the multidisciplinary team may be of benefit as well as structurally incorporating an appointment with the sexologist within the patients' schedule.

If a sexologist is not available, opt for a nurse practitioner who is specialized – or wants to further specialize – in sexual health and sexuality.

In order to create more awareness on patient sexuality within the nursing team, a working group can be arranged to give special attention to discussing the subject by organizing trainings and coaching fellow nurses to address sexuality.

Create a safe and private environment for the patient when addressing sexuality.

Educational interventions to enhance the nurses' knowledge in order to make nurses feel capable to provide basic sexuality-related patient education.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

A spinal cord injury (SCI) can have a major impact on a persons’ life. One of the consequences is that an SCI may affect sexual health and sexuality, including changes in relationships, intimacy and sexual functioning, which can eventually lead to a lower self-esteem [Citation1,Citation2]. The loss of sexual functions combined with a lower self-esteem may consequently lead to social isolation and lower quality of life, and may therefore increase the risk of a depression [Citation3–6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), sexuality is “…a central aspect of being human throughout life” which is intertwined with sexual health, which they state is “more than the absence of disease, dysfunction and infirmity” [Citation7]. The WHO also states that the sexual rights of all persons should be respected, protected and fulfilled [Citation7]. One of these sexual rights is tied to the basic human right to attain education and information [Citation7,Citation8]. Since learning how to cope with the long-term consequences of an SCI usually starts during inpatient rehabilitation, nurses could play an important role in fulfilling this right by providing patient education and information due to the intimate contact they have with their patients [Citation9,Citation10].

However, addressing patient sexuality has been shown to be difficult and usually not integrated within nursing care despite the fact that nurses are aware of the importance of discussing patient sexuality [Citation11–14]. Although barriers regarding addressing patient sexuality have already been widely reported in the past [Citation15,Citation16], a difference between the patients’ need for information and the ability of nurses to provide information still exists in modern days. Several studies among nurses working in hospitals in different cultural contexts have found that an important reason why nurses are reserved in discussing the subject is linked with discomfort [Citation12,Citation13,Citation17]. Major reasons for this discomfort are shame, inadequate knowledge, the belief that addressing the subject is improper and not being a topic of priority [Citation11,Citation13,Citation18]. These restrictions may lead to the neglect of problems regarding patient sexuality as can be seen in several studies among persons with an SCI [Citation19–21]. In these studies, persons with an SCI expressed dissatisfaction regarding the quality and quantity of sexuality-related patient education during their rehabilitation [Citation19–22].

The long known restrictions to address patient sexuality and the patients’ need for information regarding this topic urges for an elaborated understanding of the mentioned barriers in order to remove these restrictions among rehabilitation nurses, while on the other hand, existing facilitating factors should be stimulated. In the Netherlands, little is known about rehabilitation nurses’ attitudes on patient sexuality. Only a few studies have provided knowledge on barriers to discussing patient sexuality during inpatient rehabilitation, of which only one study focused on sexuality among persons with an SCI [Citation23]. However, this study used a multidisciplinary approach, in which the participant group consisted of physicians, therapists and nurses, leading to combined perceptions of addressing patient sexuality. Since similar studies have been carried out internationally and mainly among nurses in hospitals, it is still unknown whether the same barriers are experienced by Dutch nurses in SCI in-patient rehabilitation. Results of this study may show both similarities and differences with studies carried out in other cultures. This may contribute to the unification of nursing care internationally, especially in countries with similar cultural views on sexuality.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the perceptions of rehabilitation nurses regarding barriers and facilitating factors on discussing patient sexuality during the inpatient rehabilitation of persons with an SCI. With this knowledge, interventions contributing to removing these barriers and stimulating the facilitating factors could be developed. By doing so, this study consequently aims to contribute to lessening the burden for nurses to address patient sexuality, which may improve patient education in terms of sexuality and sexual health on the interest of improving the quality of life of persons with an SCI.

Method

Design

This study was an exploration of barriers and facilitating factors on discussing patient sexuality according to rehabilitation nurses. Since the barriers and facilitating factors on discussing patient sexuality during inpatient rehabilitation in the Netherlands have not been thoroughly studied yet, semi-structured interviews were used as the main data collection method to gain an extensive understanding of the nurses’ viewpoints. In order to prevent missing important information, we opted for interviews rather than surveys as interviews give the opportunity to ask probing questions. Interviews were conducted from August until October 2017.

Study setting and sampling

The study took place in the SCI department of one rehabilitation clinic in the Netherlands. Depending on the severity of the diagnosis, patients were admitted for several weeks up to 1 year. Due to the large-city location of the clinic, patients admitted in this clinic were from various cultural, ethnical and geographical backgrounds.

During the study period, 44 nurses worked at the SCI ward, including registered nurses, practical nurses and nursing students. Two registered nurses were assigned to each patient and made responsible for the coordination and evaluation of his/her care and were the primary contact persons for the patients and their families, and other disciplines. During the study period, four nurses (coach nurses) were responsible to coach fellow nurses in various nursing aspects. Furthermore, one nurse practitioner (AW) was specialized in wound care and sexuality. The nurse practitioner was consulted for both inpatient and outpatient care.

All nurses who had worked for at least 3 months at the SCI ward of a rehabilitation clinic were asked to participate. Nurses who had less than 3 months experience in the field of rehabilitation were excluded from the study as they were expected to have insufficient basic knowledge on SCI in general and thus, not expected to discuss the topic with their patients yet. We aimed to include at least 22 respondents as this was expected to give an elaborated understanding of the nurses’ perceptions on discussing patient sexuality.

Data collection and analysis

To maintain the internal consistency of the interviews, a guide based on the widely used Theory of Interpersonal Behavior of Triandis [Citation24] was developed by the research team. Triandis’ theory explains how attitudes, social factors and affect influence a person’s intention to execute certain behavior [Citation24]. This intention, combined with facilitating conditions and habits, then determines whether the person executes the desired behavior [Citation24]. Therefore, the interview guide contained the themes (1) attitude, (2) social factors, (3) affect and (4) habits and (5) facilitating conditions.

All interviews were conducted by one person (AP), as rapport with the participants had already been established since AP also worked as a nurse on the same ward. Each interview had an average duration of 45 min. All interviews took place in the clinic and were audio recorded. Field notes were taken from the moment the study was introduced to the study population until data analysis to gain a better understanding of the data [Citation25,Citation26].

The field notes and interviews were transcribed verbatim and were analyzed using framework analysis [Citation27]. The coding phase was performed by two persons (AP and AW). The themes as mentioned earlier formed the basis of the framework. To ensure consistency in coding, the two coders initially coded several transcripts independently. After the independent coding, both coders categorized the developed codes. Thereafter, the different categories were grouped together into either the existing themes or newly identified themes. The process of coding, categorizing and thematizing resulted in a new framework. This coding framework was then discussed with the research team. The remaining transcripts were divided between the two coders who applied the new framework on the transcripts. In case of new emerging data, codes were discussed and added to the framework. Findings were checked among the study population in form of two short group discussions, both led by AW. The software ATLAS.ti version 7 was used for data management.

The study was declared Exempt Review by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Slotervaartziekenhuis and Reade (P1732). Study participants were asked to give written informed consent.

Results

Twenty-five participants were interviewed. The sample mainly included intermediate vocationally trained nurses (68%). provides the demographic information of the participants.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics.

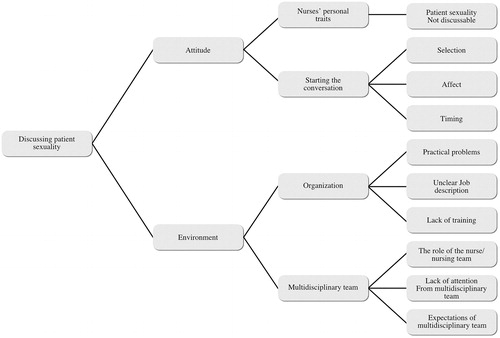

Data analysis resulted in two themes: attitude and the environment. With these themes, a distinction was made between intrinsic and extrinsic factors that affected the respondents’ behavior regarding addressing patient sexuality. ‘Attitude’ described the nurses’ views on addressing sexuality, including the main categories: (1) personality traits and (2) initiating the conversation. Personality traits referred to respondents’ personality, experience, knowledge and biological characteristics, such as age and sex. The second category addressed who should initiate the conversation on patient sexuality and with what type of patients. This also included the emotions participants experienced by talking about the subject.

The ‘Environment’ consisted of the influence of first, the organization and second, the multidisciplinary team. According to the respondents, the organization offered possibilities to make the subject more discussable. However, they also mentioned several drawbacks within the organization, which involved practical problems, a lack of training and a lack of a clear job description. The multidisciplinary team included (1) the tasks of the nursing team and (2) the perceived expectations of the multidisciplinary team towards nurses regarding addressing of patient sexuality. shows the framework with the themes and their respective (sub) categories.

Attitude

Facilitating conditions in starting the conversation

“…rehabilitation means going back to your previous lifestyle but with adjustments and that [sexuality] is part of it.” (Participant 13, Female, 24, less than five years working experience)

This quote was an example of an interviewee’s response when asked why addressing patient sexuality during inpatient rehabilitation was important. All respondents agreed on the basis of the shared opinion that sexuality is part of life and does not merely involve sexual intercourse but is rather a combination of intimacy, individual sexuality, love and relationships. This attitude towards patient sexuality was considered as a positive condition towards addressing the subject. However, only two respondents actively addressed sexuality with their assigned patients throughout their patients’ rehabilitation. Twenty-one participants explained they only actively addressed the subject with selected patients or talked about the topic in case the patient initiated the conversation. Two nurses did not discuss the subject at all.

Several conditions that facilitated the respondents’ attitude on discussing patient sexuality were found. First, the only moment in which the majority of the participants briefly addressed the subject was during patient intake. The patient intake form includes two questions regarding sexuality and reproduction, which compelled 21 respondents to address the topic. In contrast, four respondents consciously did not ask sexuality-related questions during patient intake because they felt that patient intake was an inappropriate time to address the subject. Second, twenty respondents supported the belief that nurses should initiate the conversation about sexuality during inpatient rehabilitation. The following was a quote from a participant who believed that nurses should address the subject since patients usually brushed the topic off:

“… I think the patient feels a bit ashamed and therefore says ‘I’m not ready to talk about it [sexuality]’. But if we don’t talk about it as well, it will never be discussed (…) and it’s part of the preparation for the future because on the short or long term, it will happen [being confronted with sexuality]” (Participant 14, Female, 29, less than five years working experience)

A third facilitating factor was linked to signals reflecting the patients’ need for information. Several respondents relied on these signals, consisting of emotions, questions and jokes, in order to address patient sexuality. These signals could be perceived as an opening to discuss the subject:

“But I once had a patient who was crying all the time because he found it terrible that he had not been touched anymore since his injury. And that his wife didn’t lie cozily next to him and that he couldn’t put his arms around her. So, that is very frustrating and very sad and if something like that happens, obviously, you’ll talk about it more often.” (Participant 25, female, 29, less than five years working experience)

Facilitating conditions based on personality traits

The preparedness of the participants to address patient sexuality was believed to be influenced by age, experience, one’s personality and upbringing, and knowledge. Experienced and older nurses indicated – and were perceived to – to have fewer difficulties in discussing the subject compared to young and less experienced nurses. A person’s personality and upbringing, and the lack of knowledge were reported to have a rather negative influence on addressing patient sexuality. However, a small majority stated to expand their knowledge through different measures, such as searching the Internet, asking help from experienced colleagues or others within the multidisciplinary team.

Barriers in starting the conversation

Ninety-two percent of the respondents indicated that patient sexuality was not or hardly discussable. Little attention and priority was given to the subject. Participants expressed the need to make the subject more discussable in order to integrate it into their working regime.

Interviewees claimed that the subject was rarely addressed after patient intake. The authors tried to understand the reasons why participants did not initiate the conversation while believing they should. An important hindrance was that addressing patient sexuality was described as emotionally difficult, with 44% of the respondents experiencing negative emotions (such as discomfort, fear for a negative reaction and shame), which were due to a shortage of knowledge, personality traits, and/or the taboo on sexuality.

Several respondents explained that patients might have a hesitant reaction on the nurse’s intention to address the subject. This may have caused nurses to believe that patients did not see sexuality as a problem, and were therefore not motivated to initiate the topic with their other patients:

“I’ve only done it twice [address the subject] and then it stops, you know. [That’s why] I thought other patients don’t need it as well then. (…) [Because] They both said ‘no’.” (Participant 14, Female, 29, less than five years working experience)

Furthermore, many participants made a selection in which patients they discussed sexuality with. Preconceptions on which type of patients do or do not need attention in terms of sexuality, played a major role in this selection. Common assumptions were that (1) sexuality only plays a role among younger patients as elderly are not sexually active and (2) sexuality has less priority for female patients since sexual dysfunction is more obvious among male patients. Hence, respondents believed that younger men experienced more problems and therefore more often addressed patient sexuality with them than with women:

“How I see it, they [men] find it [sexuality] more important. It’s really a subject that disturbs men, especially when they have erectile dysfunctions, so they will discuss it more easily. So mainly men, they always talk about it. Among women it could be discussed sometimes, but I always discuss it with men.” (Participant 17, Female, 28, more than five years working experience)

Other selections were made based on the diagnosis, the nurse-patient bond, the patients’ openness to talk about the subject, whether the patient had a partner, ethnical background and language barriers.

Barriers based on personality traits

As described earlier, one’s personality and upbringing, and the insufficient relevant knowledge were seen as obstacles to addressing patient sexuality. Upbringing was considered as a negative influence, describing it as a reason for being prude. Insufficient knowledge was extensively mentioned as a barrier to address the subject. Contrary to the respondents who took the initiative to expand their knowledge, others explained that they were not given any time or tools to do so. As a counterargument, one interviewee commented that she believed that the nurses’ mentality played a negative role in one’s knowledge expansion:

“…they [fellow nurses] think it’s too much. “We [nurses] just have to do our work and that’s it”. (…) I think that is the mentality of nurses, they think “I already have to work so hard, I’m really not going to read things as well-”. (…) I think it’s very strange that they don’t look things up because they don’t have time for it at work.” (Participant 1, Female, 28, more than five years working experience)

Therefore, participants expressed the need for training regarding patient sexuality, which leads us to the ‘environment’.

Environment

Facilitating conditions

Nearly all respondents confirmed they played a role in addressing patient sexuality, claiming to be the ones to observe signals and to either provide information or refer to other disciplines. Interviewees shared the common opinion that nurses should be the ones to give basic patient education. Profound questions regarding medical interventions, and psychological concerns were reasons to refer to the nurse practitioner, the physician or social worker. Nevertheless, 18 participants stated that the initiative to make patient sexuality discussable was especially a task reserved for the responsible nurses. In contrast, some wondered whether nurses should be the ones addressing patient sexuality due to the intensive contact they have with patients. They explained that taking responsibility for addressing patient sexuality might become too intimate for both themselves and the patient, suggesting that the task of discussing sexuality should be assigned to another discipline.

Barriers within the organization

Organizational efforts. Respondents agreed that discussing patient sexuality should be encouraged within the organization. The organization encouraged nurses to address patient sexuality in several ways. Despite these efforts, respondents found these measures to be insufficient. For example, although the patient intake form forced the participants to address the subject, they indicated that the sexuality-related questions in the form were too confronting. One interviewee explained that asking the questions from the intake form literally led to a negative reaction from a patient:

“…then people often become angry and say ‘well hello, can’t you see? I just had an SCI’. Especially among younger men when you ask it like that. So actually, I think you mustn’t ask the question like that. (Participant 19, Male, 45, more than five years working experience)

This may indicate that the questions regarding sexuality and reproduction should be reformulated to make them less confronting.

Other measures were the provision of patient leaflets regarding sexuality and the provision of patient questionnaires after a weekend leave to assess whether the patient had experienced any problems at home. However, the leaflets were often overlooked, with nine nurses even maintaining they were unaware of the leaflets. As for the questionnaires, patients often answered the sexuality-related question with ‘Not applicable’, according to the interviewees. One participant explained that asking a private question through a questionnaire was not the right way to assess problems:

“Well, people often write ‘no problem, no problem, no problem’. I have never seen something written there [sexuality-related question]. And I don’t think that’s the right way [to ask], because that piece of paper can be read by anyone. And if you yourself would have any problems [with sexuality], you wouldn’t write it down either.” (Participant 23, Female, 30, more than five years working experience)

Participants were unaware of what happened with the questionnaires since they never received feedback on what the patient had written. Surprisingly, the respondents usually did not discuss the filled-in questionnaires with patients themselves, although being the first ones to receive them.

A frequently mentioned suggestion to incorporate patient sexuality during rehabilitation was to structurally include sexuality in a patient’s therapy schedule. The following respondent believed this would it make less difficult for the patient to initiate the conversation as it had already been planned:

“You don’t ask for physical therapy, you don’t ask for occupational therapy or for a social worker. So, you mustn’t HAVE to ask for this as well, right? It just has to be in the schedule.” (Participant 13, Female, 24, less than five years working experience)

Practical problems. Respondents felt hindered to discuss sexuality due to several practical issues, an unclear job description and a lack of training. Respondents declared that patient sexuality should be discussed in a safe environment but deemed this impossible due to the high workload and the shortage of private rooms. The following quote is an example given by a respondent that both the lack of time – due to heavy workload – and the lack of privacy – due to the absence of private rooms – were disruptive factors in creating a safe environment:

“Because if they [the patient] initiate the conversation, you have to have a room to talk about it. You can’t just address it and then say [when beeper goes off] ‘oh, a patient’s calling, I’m going’, you know. No, that’s difficult at times.” (Participant 21, Female, 55, more than five years working experience)

Unclear job description. Moreover, discussing sexuality was described to be a ‘grey area’. A small majority (52%) commented that it was unclear whose task it was to address patient sexuality. Therefore, some participants indicated that it should be explicitly written in the nurses’ job description if it is indeed their task to discuss the subject. Few participants opted for a protocol, which e.g., included which questions should be asked and when patient sexuality should be discussed during inpatient rehabilitation:

“What’s our goal by discussing it [sexuality]? I would like to have that clear. And eh, for example, which information can you give as a nurse? And which questions should or shouldn’t you ask? You know, like that. like an instruction manual or something. (…) I think that would make it [addressing sexuality] a bit easier.” (Participant 10, Female, 57, more than five years working experience)

Lack of training. Twenty-four participants expressed their need for training regarding patient sexuality. Notable was that the desired training concerned skills to start a conversation rather than physiological processes and interventions. Training was seldom given and since there was rarely knowledge transfer among the nurses after a training, the lack of knowledge remained, as one interviewee commented that “it will all depend on the only [for example] two nurses who had the training and after that nothing will happen” (Parcticipant 16, Male, 28, less than five years working experience). This suggests that frequent training sessions are needed to guarantee the success of the training.

On the other hand, the clinic had organized frequent information meetings for patients during inpatient rehabilitation in the past. These meetings covered different aspects of SCI, including sexuality. The following respondents believed that frequent meetings were effective as patients were given the freedom to choose to attend the meetings:

“You’re [the patient] in a big group and you’re being protected by the group. So you hear the possibilities- and you can learn from it.” (Participant 6, Female, 60, more than five years working experience)

“I think for the patients- you have to offer it more often [information meetings] because the first time they might not [attend]– when you’re here for the first two weeks and there’s an information gathering about sexuality, I can imagine you might think ‘I’m happy that I can move my head, why would I think about that’.” (Participant 18, Female, 64, more than five years working experience)

However, participants noticed that the frequency of these information gatherings had decreased. Some respondents did not even know of the gatherings. In addition, meetings were not promoted efficiently, making it more difficult for participants to motivate patients to attend them. The respondents therefore shared a common view that these information meetings should be frequently organized and promoted among both the patients and the nursing team.

Barriers within the multidisciplinary team

Almost all respondents indicated that patient sexuality should be discussable within the multidisciplinary team since patients should be given the possibility to talk about the subject with someone they trust. However, respondents felt that other members of the multidisciplinary team expected it to be the nurses’ task to address patient sexuality due to being the discipline ‘that sees the patient 24/7’. Considering the uncertainty whose task it is to address patient sexuality, more awareness has to be created within the whole multidisciplinary team according to the participants.

Another barrier was linked to the coach nurses. Respondents did not feel coached by the coach nurses concerning this topic, nor did the interviewed coach nurses (n = 3) state that nurses asked for their help. One respondent claimed that coach nurses had the same difficulties discussing the subject and were therefore not capable to coach others:

“They [coach nurses] could also address it but that doesn’t happen so I don’t think it’s their task to coach us. I think we’re equal and we need someone from a higher position, like [name nurse practitioner], who will provide us with information.” (Participant 12, Female, 23, less than five years working experience)

Nevertheless, coach nurses were expected to bring more attention to patient sexuality due to their role within the nursing team.

shows a summarizing overview of the facilitating conditions and barriers in terms of addressing patient sexuality.

Table 2. Summary of facilitating conditions and barriers.

Discussion

We explored both the facilitating conditions and difficulties rehabilitation nurses experienced in terms of addressing patient sexuality. The nurses either felt motivated or hindered to discuss the subject not only due to their own attitude towards sexuality but due to organizational aspects as well. This study shows that discussing patient sexuality remains difficult and is inadequately or not embedded in nursing care.

Although our respondents acknowledged that discussing patient sexuality should be integrated within rehabilitation care, they felt neither the nursing team nor the organization paid sufficient attention to the subject to do so. The results of this study are largely in agreement with those from the study of Schuurman and Rabsztyn [Citation23], which was conducted among the multidisciplinary team of the SCI ward of another Dutch rehabilitation clinic. The majority of our respondents felt it was their task to address patient sexuality, to provide basic patient education and that they played a signaling role. Nurses in different rehabilitation clinics were considered to play a central role in discussing patient sexuality although they rarely initiated the conversation [Citation22]. This could be explained by the taboo placed on sexuality, which in our study resulted in the uneasiness to address the subject and the lack of attention given to it by both the organization and the nursing team. The lack of attention given by the organization and the nursing team also included the lack of organization of sexuality-related education and thus, insufficient knowledge, resulting in the felt incapability of nurses to address patient sexuality like in other studies [Citation11–13,Citation17,Citation18,Citation23,Citation28]. In our study, a part of the taboo comprised certain assumptions about which patient categories were believed to be interested in the subject, such as prejudices regarding the patients’ age and sex. However, Bender et al. [Citation22], who also studied the experiences of patients in Dutch rehabilitation centers, showed that there were no major differences between the patients’ gender and age in terms of sexuality-related problems. Therefore, by maintaining these assumptions, patients may easily be overlooked and not receive any sexuality-related information at all during inpatient rehabilitation. According to Emerich et al. [Citation29], in order to provide competent care to persons with SCI, nurses should have experience in providing information about sexuality and fertility. Hence, the importance of enhancing the nurses’ knowledge and breaking the taboo on patient sexuality should be emphasized, which in turn may lead to more initiative from nurses to address the subject. However, this does not mean that addressing patient sexuality is solely reserved for rehabilitation nurses, but is rather a subject that preferably should also be included and elaborated on in psychosocial services provided by psychologists and social workers [Citation29].

Several reflections can be made on the methodological aspects of this study. First, the interviews were all conducted by AP, who also worked as a nurse in the same ward. This could have led to socially desirable answers by respondents to gain approval from a fellow nurse. Nevertheless, this did not take away the fact that respondents found it difficult to address the subject during inpatient rehabilitation. In addition, study participants indicated they would be more comfortable to talk about the subject with a familiar person. Therefore, AP remained the person to conduct all the interviews.

Second, since the interviews took place during day shifts, respondents were under time pressure during the time of the interviews. In some cases, this led to short interviews in which we missed the opportunity to extract more data. However, data saturation was reached far before the desired number of participants.

Third, the majority of our respondents were females. We were not able to include more male nurses, as there were only four male nurses employed at the time whom all participated in this study. Therefore, we were not able to create equal numbers of participants in the male and female group. In this study we did not find differences in perceptions between the two sexes. However, considering the unequal distribution of male and female participants, we cannot draw a conclusion on the differences in perceptions between male en female nurses.

A last limitation could be that this study was executed in a single center. To enable generalization of the results, we could have opted for a multicenter study. However, since our findings are in line with the results of similar Dutch studies in this field [Citation22,Citation23,Citation28] we can suggest that rehabilitation nurses in general may experience the same barriers and motivating factors in regard to discussing patient sexuality. The literature shows us that discussing patient sexuality remains difficult for nurses from various cultural settings. The Netherlands has a tolerant social view towards sexuality, wherein parents tend to openly discuss sexuality and relationships with their children. Furthermore, mandatory sexual education is incorporated within the education system. Despite the Dutch liberal view towards sexuality, our study together with the studies of Bender et al. [Citation22], Hoekstra et al. [Citation28] and Schuurman and Rabsztyn [Citation23], shows that the taboo is still present in healthcare. Studies conducted in countries with a more conservative view towards sexuality such as Turkey [Citation30,Citation31] and China [Citation32], show that taboo is the main reason nurses do not discuss the subject with their patients. In our study, the nurses considered the lack of training and knowledge as an important barrier to discuss patient sexuality rather than the patients’ ethnical background. This may indicate that different countries may require different interventions to tackle the barriers of discussing sexuality within healthcare.

To our knowledge, this was the first study that explored both the barriers and facilitating conditions specifically among Dutch SCI rehabilitation nurses regarding addressing patient sexuality. Noting that the mentioned barriers have already been widely reported in the past [Citation33,Citation34], it can be concluded that it is time to remove these barriers. To remove these obstacles, several quantifying measures should be applied, such as the cultural validation of internationally valid scales i.e., the Sexual Attitudes and Beliefs Survey [Citation35], which is described to be a valid tool in assessing sexual attitudes and beliefs in clinical nursing practice. This scale could be used to evaluate and gain insight in the effects of interventions targeted at improving the addressment of patient sexuality. Interventions should include knowledge-expansion measures contributing to the nurses’ knowledge regarding sexuality, and the incorporation of patient sexuality within the treatment program.

Based on the results of this study, several implications for clinical practice can be made. Since there is much uncertainty among nurses on whose task it is to address patient sexuality, working agreements within the multidisciplinary team should be made. Adding a sexologist in the multidisciplinary team may be of benefit. When a sexologist is not available, a suggested option is to train a nurse practitioner to specialize in sexual health and sexuality. In addition, a working group focusing on patient sexuality can be established within the nursing team. This group may consist of several nurses whose tasks are to give special attention to discussing the subject with patients by organizing trainings and coaching fellow nurses to address sexuality. Members of the working group may also be appointed to initiate conversations with patients regarding sexuality. Furthermore, a protocol may help in addressing sexuality before a patient is discharged. Educational measures should be undertaken frequently to both create awareness and to enhance the nurses’ knowledge. This would contribute to making nurses feel more capable to provide basic sexuality-related patient education.

Patients must also be given the opportunity to talk about the subject in a safe and private environment. This means that there should be a designated room in the ward, which can be reserved for various conversations with patients – and their families. For instance, patient intake, care evaluation and other conversations where privacy is needed.

Conclusion

Breaking the taboo on sexuality in a clinical setting is an essential part in order to provide holistic care. Nurses consider discussing patient sexuality an important part of their job. However, patient sexuality remains difficult to integrate within nursing practice due to multiple factors. Organizational efforts should be carried out or improved. This could contribute to the enhancement of the nurses’ knowledge and could subsequently influence their attitude on addressing patient sexuality. Although nurses may not have to discuss the subject in an extensive matter, they generally possess sufficient communication skills to address sensitive subjects. By embedding patient sexuality within the patients’ treatment program, patients are given the opportunity to talk and think about the subject, which could intercept possible sexuality-related problems and might therefore improve their quality of life.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Molleman for her assistance throughout the study period. We would also like to show our gratitude to the nurses of the SCI ward of Rehabilitation Center Reade for participating in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Siosteen A, Lundqvist C, Blomstrand C, et al. Sexual ability, activity, attitudes and satisfaction as part of adjustment in spinal cord-injured subjects. Paraplegia. 1990;28:285–295.

- Singh U, Gogia VS, Handa G. Occult problem in paraplegia- a case report. Indian J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;13:19–23.

- Shabsigh R, Zakaria L, Anastasiadis AG, et al. Sexual dysfunction and depression: etiology, prevalence, and treatment. Curr Urol Rep. 2001;2(6):463–467.

- Burns SM, Hough S, Boyd BL, et al. Sexual desire and depression following spinal cord injury: masculine sexual prowess as a moderator. Sex Roles. 2009;6:120–129.

- Hess MJ, Hough S. Impact of spinal cord injury on sexuality: broad-based clinical practice intervention and practical application. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35(4):211–219.

- Bae H, Park H. Sexual function, depression, and quality of life in patients with cervical cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1277–1283.

- World Health Organization. Defining sexual health Report of a technical consultation on sexual health 28–31 January 2002, Geneva. Sexual Health Documents Series [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2016 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sexual_heatth.pdf

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Sexual rights: an IPPF declaration [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2016 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/sexualrightsippfdeclaration_1.pdf

- Ricciardi R, Szabo CM, Poullos AY. Sexuality and spinal cord injury. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(4):675–684.

- Torriani SB, Britto FC, Aguiar da Silva G, et al. Sexuality of people with spinal cord Injury: knowledge, difficulties and adaption. JBiSE. 2014;07(06):380–386.

- Katz A. Do ask, do tell: why do so many nurses avoid the topic of sexuality? Am J Nurs. 2005;105(7):66–68.

- Magnan MA, Reynolds K. Barriers to addressing patient sexuality concern across five areas of specialization. Clin Nurse Spec. 2006;20(6):285–292.

- Saunamaki N, Andersson M, Engström M. Discussing sexuality with patients: nurses’ attitudes and beliefs. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1308–1316.

- Ayaz S. Sexuality and nursing process: a literature review. Sex Disabil. 2013;31(1):3–12.

- Gender AR. An overview of the nurse’s role in dealing with sexuality. Sex Disabil. 1992;10(2):71–79.

- Waterhouse J. Nursing practice related to sexuality: a review and recommendations. J Nursing Res. 1996;1(6):412–418.

- Washington M, Pereira E. A time to look within curricula—Nursing students’ perception on sexuality and gender issues. OJN. 2012;02(02):58–66.

- Algier L, Kav S. Nurses’ approach to sexuality-related issues in patients receiving cancer treatments. Turk J Cancer. 2008;38:135–141.

- Otero-Villaverde S, Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Montoto-Marqués A, et al. Sexual satisfaction in women with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(7):557–560.

- McAlonan S. Improving sexual rehabilitation services: the patient’s perspective. Am J Occup Ther. 1996;40:826–834.

- Myburgh JG, Fourie R, Niekerk van AH. Efficacy of sexual counselling during the rehabilitation of spinal cord injured patients. South Afr Orthop J. 2010;9:46–48.

- Bender J, Hoïng M, Dam A van, et al. Is revalidatie aan seks toe? Revalidata. 2004;121:20–26.

- Schuurman KSE, Rabsztyn P. Hoe bespreekbaar is seksualiteit in de zorgrelatie tussen professional en dwarslaesiepatiënt? Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Revalidatiegeneeskunde. 2016;38:105–109.

- Triandis HC. Interpersonal behavior. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co; 1977.

- Gray DE. Doing research in the real world. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2014.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitatieve methods for health research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2014.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

- Hoekstra T, Visser-Meily JMA, Kanselaar MA, et al. Is seksualiteit bespreekbaar in de CVA-zorg in revalidatiecentra? Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Revalidatiegeneeskunde. 2011;6:5–9.

- Emerich L, Parsons K, Stein A. Competent care for persons with spinal cord injury and dysfunction in acute inpatient rehabilitation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2012;18(2):149–166.

- Arikan F, Meydanlioglu A, Ozcan K, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of nurses regarding discussion of sexual concerns of patients during hospitalization. Sex Disabil. 2015;33(3):327–337.

- Evcili F, Demirel G. Patient’s sexual health and nursing: a neglected area. Int J Caring Sci. 2018;11:1282.

- Zeng YC, Li Q, Wang N, et al. Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34(2):E14–E20.

- Alexander CJ, Sipski ML, Findley TW. Sexual activities, desire, and satisfaction in males pre-and post-spinal cord injury. Arch Sex Behav. 1993;22(3):217–228.

- Herson L, Hart KA, Gordon MJ, et al. Identifying and overcoming barriers to providing sexuality information in the clinical setting. Rehabil Nurs. 1999;24(4):148–151.

- Reynolds KE, Magnan MA. Nursing attitudes and beliefs toward human sexuality: collaborative research promoting evidence-based practice. Clin Nurse Spec. 2005;19(5):255–259.