Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate to what extent psychological factors are related to pain levels prior to non-invasive treatment in patients with osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint.

Methods

We included patients (n = 255) at the start of non-invasive treatment for osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint who completed the Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire. Psychological distress, pain catastrophizing behavior and illness perception was measured. X-rays were scored on presence of scaphotrapeziotrapezoid osteoarthritis. We used hierarchical linear regression analysis to determine to what extent pain levels could be explained by patient characteristics, X-ray scores, and psychological factors.

Results

Patient characteristics and X-ray scores accounted for only 6% of the variation in pre-treatment pain levels. After adding the psychological factors to our model, 47% of the variance could be explained.

Conclusions

Our results show that psychological factors are more strongly related to pain levels prior to non-invasive treatment in patients with osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint than patient characteristics and X-ray scores, which implies the important role of these factors in the reporting of symptoms. More research is needed to determine whether psychological factors will also affect treatment outcomes for patients treated non-invasively for osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint.

Pain is the most important complaint for patients with osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint.

Psychological factors are strongly associated with pain levels prior to treatment.

Pain catastrophizing behavior appears to be a promising target for complementary treatment in patients with osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint (CMC-1 OA) is a degenerative disease that causes pain and loss of function [Citation1]. Patients are initially treated non-invasively [Citation2] with hand therapy, occupational therapy, an orthosis, or a combination of treatment modalities [Citation3]. Non-invasive treatment is an effective treatment that may prevent the need for surgical treatment [Citation4] and reduces pain in a selection of patients [Citation5].

At the start of the treatment, considerable variation in pain levels between patients is seen [Citation5]. However, traditional patient and disease attributes, e.g., age, grip strength, and X-ray scores, only explain a small amount of the variation in reported pain and disability, which suggests other factors are at play [Citation6,Citation7]. It is currently unclear which factors are associated with pain for CMC-1 OA patients.

Several studies on surgical treatment of OA, including total knee or hip replacement [Citation8–11] and surgery for CMC-1 OA [Citation12,Citation13] found that psychological factors (e.g., depression, pain catastrophizing behavior, and illness perception) are associated with worse patient reported outcomes, both before and after treatment. Moreover, recent studies suggested that interventions improving catastrophizing behavior [Citation14] and negative illness perception [Citation15] have a beneficial effect on OA symptoms.

Although there is evidence for the association between psychological factors and symptom severity in knee and hip OA, little is known regarding this association for patients treated non-invasively for CMC-1 OA [Citation16,Citation17]. In particular, the association between psychological factors and pain, which is the primary complaint of CMC-1 OA patients [Citation18], is currently unknown. Moreover, while illness perceptions have been shown to be important factors in other conditions, like knee OA, no studies have investigated to what extent illness perceptions are associated with pain in this patient population [Citation11]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate to what extent psychological distress, pain catastrophizing behavior and illness perceptions are associated with pain levels prior to non-invasive treatment in CMC-1 OA patients.

Methods

Setting and study population

This cross-sectional study was performed at Xpert Clinic in The Netherlands. Xpert Clinic is a specialized private treatment center for hand and wrist conditions. Xpert Clinic has 20 different locations, with 20 European Board certified (Federation of European Societies for Surgery of the Hand) hand surgeons and over 150 hand therapists.

All patients who received non-invasive treatment, consisting of orthosis and/or hand therapy, for CMC-1 OA at Xpert Clinic between September 2017 and July 2018 were invited to complete several questionnaires as part of routine clinical care to measure symptom severity, psychological status, understanding of disease and quality of life prior to treatment. These questionnaires were e-mailed after the first consultation and before non-invasive treatment started. Three reminders were e-mailed to non-responders. Furthermore, baseline demographics, including age, sex, hand dominance and occupational intensity were collected. Occupational intensity was classified by the hand therapist in one of the following categories: not employed, light occupational intensity (e.g., working in an office), moderate occupational intensity (e.g., working in a shop) or severe occupational intensity (e.g., construction work). All patients provided written informed consent.

Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire

The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ) [Citation19] is a patient reported outcome measure with six domains (pain, aesthetics, hand function, performance of activities of daily living, work performance, and satisfaction) with good validity, reliability, and responsiveness in CMC-1 OA patients [Citation20]. Scores range from 0 to 100 (0 = poorest function, 100 = ideal function). In the present study, the pain scores were reversed (0 = no pain, 100 = extreme pain).

The MHQ pain subscale was used as primary outcome measure, because pain is the primary complaint and the main reason to seek treatment for CMC-1 OA patients [Citation18]. To also see if there is an association between psychological effects and patient reported hand performance, we used the total MHQ score as secondary outcome measure.

Patient Health Questionnaire-4

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ) [Citation21] is a generic depression- and anxiety-screening tool and was used to measure psychological distress. This questionnaire is a combination of two brief screening tools (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2). The PHQ contains two domains (anxiety and depression) with two questions each. The total score ranges from 0 to 12 (0 = no indication for psychological distress; 12 = strong indication for psychological distress). It has a good reliability and validity in the general population [Citation22].

Pain Catastrophizing Scale

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [Citation23] was used to assess catastrophizing behavior in response to pain. This questionnaire consists of 13 questions and 3 domains (helplessness, magnification, and rumination). It has been demonstrated to have good validity, reliability and responsiveness in patients with pain related problems [Citation24,Citation25]. The total score ranges from 0–52 (0 = no catastrophizing behavior; 52 = severe catastrophizing behavior).

Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaires (B-IPQ) [Citation26] was used to assess the patients’ perceptions of illness. This questionnaire is a short version of the Revised Illness perception Questionnaire [Citation27]. In the B-IPQ, each subscale of the Revised Illness perception Questionnaire is summarized by one question. Five questions assess cognitive illness representation, two questions assess emotional representations, one question assesses understanding of disease and in the final question patients are asked to list the factors they believe to have caused their illness. This last question was not part of our questionnaire. Reliability and validity have been demonstrated for multiple conditions, including low back pain, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation28–31].

CMC-1 joint X-rays

The patients’ records were searched for X-rays of the first carpometacarpal joint. If multiple X-rays were present, we selected the X-ray in which both the CMC-1 joint and the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint (STT) were most clearly visible. The Eaton-Glickel classification [Citation32] ranges from stage I to stage IV. Stage III is defined as excessive CMC-1 degeneration and subluxation. Stage IV is defined as stage III with additional presence of STT OA. According to this classification, presence of STT OA indicates the most advanced stage of structural damage. Therefore, we used this feature as indication of radiographic severity of disease. The first 100 X-rays were independently scored by both a European Board-certified hand surgeon (G. V.) and a junior scientist (L.H.). The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient was 0.58 (95% CI 0.49–0.65). This is in agreement with the study by Dela Rosa et al. [Citation33], who reported fair to moderate inter-observer agreement for the Eaton-Glickel classification, with similar agreement rates for stage I, III and IV. The scores of the junior scientist were used for all patients. Patients without an X-ray of the CMC-1 joint were excluded.

Statistical analyses

A complete case analysis was performed with patients who completed all previously mentioned questionnaires. To see whether patients with missing data differed from patients with complete data, two non-responder analyses were performed; both for patients who completed the MHQ, but did not complete the psychological questionnaires and for patients who completed all questionnaires, but without X-ray of the CMC-1 joint. For these analyses, T-tests were used for normally distributed continuous data and Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests were used for continuous data that was not normally distributed. Chi square statistics were used for categorical data. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients to determine to what extent the psychological variables were correlated.

Data were analyzed using hierarchical linear regression analyses with baseline MHQ-pain levels as a dependent variable. In the first step of the analysis, age, sex, and occupational intensity were entered into the model. The presence of STT OA was added in the second step of analysis. In the third step, we entered the total PHQ score, as well as the total PCS score. In the fourth step, all B-IPQ subscales were added in order to determine the effect of illness perceptions on pain, after correcting for psychological distress and pain catastrophizing behavior.

For all variables, the regression coefficients (B) are reported, which represents the increase in the dependent variable for one unit increase in the independent variable, when all other variables remain constant. In order to compare the relative contribution of each explanatory variable on the outcome, the standardized regression coefficients (β) are also reported. Standardized regression coefficients allow for comparison of the strength of associations when the independent variables were measured on different scales. For all models, both the multiple explained variance (R2) and the explained variance adjusted for number of variables in the model (adjusted R2) is calculated.

All analyses were performed using R statistical computing, version 3.4.1. For all tests, a p-value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Non-responder analysis

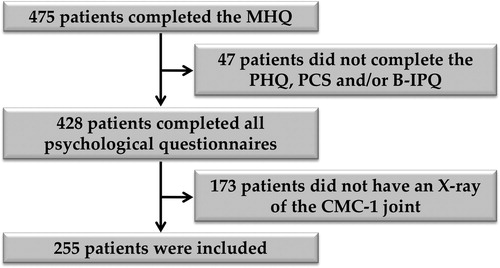

We identified 475 patients at the start of non-invasive treatment for CMC-1 OA who had completed the MHQ. 5.2% of these patients did not complete all psychological questionnaires. Of the patients who completed all questionnaires, 40.4% did not have an X-ray of the CMC-1 joint. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 show demographic characteristics and MHQ scores for responders and non-responders, indicating no significant differences in any patient characteristic or MHQ-pain scores between responders and non-responders.

Patient characteristics

Two hundred and fifty-five patients were included in the analysis (). Their mean age was 60 ± 8 years (mean ± SD) and 75% of the patients were female. The mean MHQ-pain score was 52.9 ± 17.3 and the mean total MHQ score was 59.7 ± 15.2. shows baseline characteristics for all included patients. Correlations between the psychological factors ranged from −0.24 to 0.60 (Supplemental Table 3), which can be interpreted as weak to moderate correlations [Citation34].

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients included for analysis.

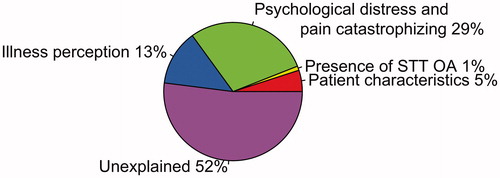

Hierarchical linear regression

shows the outcomes of the hierarchical regression analysis. In models 1 and 2, female sex was statistically significantly associated with higher MHQ-pain scores. However, after adding psychological distress and catastrophizing behavior to the model, sex was no longer statistically significantly related to pain, while higher PHQ and PCS scores were statistically significantly associated with higher MHQ-pain scores. After adding the B-IPQ subscales to the model, B-IPQ subscales ‘consequences’ and ‘identity’ were, in addition to PHQ score and PCS score, also statistically significantly associated with pain. shows the increase in explained variance per model. Models 1 and 2 had an explained variance of 5% and 6%, respectively. After adding psychological distress and catastrophizing behavior, the explained variance increased to 35%, and after adding illness perceptions, the explained variance increased to 47%. In this model, more psychological distress (PHQ score, B = 0.79), more pain catastrophizing behavior (PCS score, B = 0.46), experiencing more consequences (B-IPQ ‘consequences’, B = 1.36) and more symptoms (B-IPQ ‘identity’, B = 1.11) were statistically significantly associated with higher MHQ-pain scores. Of all significant variables in the final model, total PCS score had the largest standardized regression coefficient (β = 0.27) in this model, indicating that pain catastrophizing behavior has the largest independent effect on pre-treatment pain of all variables investigated in this study.

Figure 2. Increase in explained variance (increase in multiple R2) of pre-treatment MHQ-pain per step in the hierarchical linear regression model.

Table 2. Beta coefficients and explained variance (R2) for hierarchical linear regression models explaining pre-treatment pain levels.

We found similar associations in the hierarchical linear regression analysis on total MHQ score. Further details are reported in Supplemental Table 4.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate to what extent psychological factors are related to pre-treatment pain levels in patients receiving non-invasive treatment for CMC-1 OA. After controlling for patient characteristics and radiographic severity of OA, we found that higher psychological distress, more pain catastrophizing behavior and experiencing more consequences and symptoms from the illness were independently associated with higher pre-treatment pain levels. Pain catastrophizing behavior has the strongest association with pre-treatment pain. Patient characteristics and radiographic severity of the disease had no additive predictive value for pre-treatment pain.

Several previous studies focused on the association between X-ray scores and pain in patients with CMC-1 OA. However, different methods are available to score X-rays [Citation35] and the available literature is conflicting [Citation6,Citation7,Citation36–39]. Several radiographic OA features including erosions and sclerosis have been linked to pain levels [Citation36,Citation39], while Dahaghin et al. [Citation7] in a large population study (n = 3906) reported that radiographic OA was poorly correlated with pain. In our study, we found that the presence of STT OA could only explain a limited amount of variance in pain scores. Possibly, other radiographic OA features have a stronger association with pain and would, therefore, be more informative. However, as the presence of STT OA is a clear indication of advanced CMC-1 OA in the Eaton-Glickel classification [Citation32], we expected a stronger association between presence of STT OA and pain in CMC-1 OA patients. While X-rays may still have an important role in clinical practice, our study indicates that their value for understanding pain scores is limited.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed pre-treatment pain in CMC-1 OA patients that included both radiographic severity and psychological factors in the analysis. Murphy et al. [Citation40] performed a similar study for women with knee OA. They found that fatigue, sleep quality and depression explained additional variance in pain severity after correcting for age and X-ray scores. This is in line with our findings that psychological factors explained additional variance in pre-treatment pain. However, in our study we found that psychological factors explained an additional variance of 40% compared to 10% in Murphy et al., which may be explained by use of different definitions of psychological variables in both studies.

Becker et al. [Citation17] reported that symptom severity could largely be explained by whether or not the patients sought treatment for his symptoms and by pain catastrophizing behavior. This is in agreement with our finding that pain catastrophizing behavior has the strongest association with pre-treatment pain of all variables included in our study.

While no studies reported the association between pain and illness perceptions for patients with CMC-1 OA, Hill et al. [Citation41] found that higher pain levels were associated with reporting more frustration, experiencing more consequences and expecting a chronic timeline in people with musculoskeletal hand problems.

The strength of this study is the large population where we combined psychological distress, pain catastrophizing as well as illness perceptions in explaining pre-treatment pain in non-invasively treated CMC-1 OA. Moreover, we included the presence of STT OA in our analyses as a measure for structural damage to the CMC-1 joint. To our knowledge, this is the first study that combined psychological factors and radiographic severity of disease to explain pre-treatment pain levels of CMC-1 OA patients.

Study limitations

A limitation of our study is the quality of the X-rays that we used to score presence of STT OA. These X-rays were taken as part of daily clinical practice and, therefore, not taken in a standardized way, making it difficult to score all radiographic OA features. For that reason, we only scored presence of STT OA, because presence of STT OA is an indication that radiologically the disease has reached an advanced stage [Citation32]. Still our study clearly demonstrates that the presence of STT OA, on X-rays taken as part of routine care, is not related to pre-treatment pain, whereas psychological factors show a strong association with pre-treatment pain.

In addition, it is not possible to draw any causal implications from our research findings due to the cross-sectional design of our study. While our study demonstrates a strong association between pre-treatment pain levels and psychological factors, more research is needed to determine the direction of this association.

Future research

Based on the strong association between pre-treatment pain and treatment outcomes in our study and in previous studies [Citation17,Citation23,Citation31], the question arises whether psychological factors will affect treatment outcomes and consequently, whether treatment results will improve when patients receive psychological support in addition to usual care. A large prospective study may provide valuable knowledge of the longitudinal association between psychological factors and pain and can be used to answer the research questions of interest.

Moreover, future studies have to demonstrate what type of psychological intervention would improve pain levels most in non-invasively treated CMC-1 OA patients, while also being feasible to offer in addition to usual care. This study suggests that pain catastrophizing behavior is the most important factor to target with a psychological intervention, but psychological distress and/or negative illness perceptions may be relevant targets for intervention as well.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that patient characteristics and X-rays have limited value for understanding pain in patients with CMC-1 OA. In contrast, we found a strong association between psychological factors and pain levels prior to non-invasive treatment. Clinicians should be aware of the strong relation between pain and psychological factors and should look beyond X-ray scores to judge pain intensity in patients with CMC-1 OA.

Supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors thank all patients who participated and allowed their data to be anonymously used for the present study. The members of the Hand-Wrist Study Group are Arjen Blomme, Berbel Sluijter, Corinne Schouten, Dirk-Jan van der Avoort, Erik Walbeehm, Gijs van Couwelaar, Guus Vermeulen, Hans de Schipper, Hans Temming, Jeroen van Uchelen, Luitzen de Boer, Nicoline de Haas, Oliver Zöphel, Reinier Feitz, Sebastiaan Souer, Steven Hovius, Thybout Moojen, Xander Smit, Rob van Huis, Pierre-Yves Pennehouat, Karin Schoneveld, Yara van Kooij, Robbert Wouters, Paul Zagt, Folkert van Ewijk, Frederik Moussault, Rik van Houwelingen, Joris Veltkamp, Arenda te Velde, Alexandra Fink, Harm Slijper, Ruud Selles, Jarry Porsius, Kim Spekreijse, Chao Zhou, Jonathan Tsehaie, Ralph Poelstra, Miguel Janssen, Mark van der Oest, Stefanie Evers, Jak Dekker, Matijs de Jong, Jasper van Gestel, Marloes ter Stege, Menno Dekker, Roel Faber, Frank Santegoets, Monique Sieber-Rasch, and Ton Gerritsen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anakwe RE, Middleton SD. Osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb. BMJ. 2011;343:d7122.

- van Uchelen J, Beumer A, Brink SM, et al. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Plastische Chirurgie (NVPC); 2014. Available from: https://www.nvpc.nl/uploads/stand/150416DOC-MB-Definitieve_richtlijn_Conservatieve_en_Chirurgische_behandeling_duimbasisartrose_28-10-2014_aangenomen_ALV_14_april_2015149.pdf.

- Aebischer B, Elsig S, Taeymans J. Effectiveness of physical and occupational therapy on pain, function and quality of life in patients with trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hand Ther. 2016;21(1):5–15.

- Berggren M, Joost-Davidsson A, Lindstrand J, et al. Reduction in the need for operation after conservative treatment of osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint: a seven year prospective study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35(4):415–417.

- Tsehaie J, Spekreijse KR, Wouters RM, et al. Outcome of a hand orthosis and hand therapy for carpometacarpal osteoarthritis in daily practice: a prospective cohort study. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(11):1000–1009.e1.

- Jones G, Cooley HM, Bellamy N. A cross-sectional study of the association between Heberden's nodes, radiographic osteoarthritis of the hands, grip strength, disability and pain. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2001;9(7):606–611.

- Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Ginai AZ, et al. Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):682–687.

- Bierke S, Petersen W. Influence of anxiety and pain catastrophizing on the course of pain within the first year after uncomplicated total knee replacement: a prospective study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137(12):1735–1742.

- Hernandez C, Diaz-Heredia J, Berraquero ML, et al. Pre-operative predictive factors of post-operative pain in patients with hip or knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:361–380.

- Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ, et al. Predictors of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):551–561.

- Hanusch BC, O’Connor DB, Ions P, et al. Effects of psychological distress and perceptions of illness on recovery from total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):210–216.

- London DA, Stepan JG, Boyer MI, et al. The impact of depression and pain catastrophization on initial presentation and treatment outcomes for atraumatic hand conditions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(10):806–814.

- Oh Y, Drijkoningen T, Menendez ME, et al. The influence of psychological factors on the Michigan Hand Questionnaire. Hand (New York, N,Y). 2017;12(2):197–201.

- Broderick JE, Keefe FJ, Bruckenthal P, et al. Nurse practitioners can effectively deliver pain coping skills training to osteoarthritis patients with chronic pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Pain. 2014;155(9):1743–1754.

- de Raaij EJ, Pool J, Maissan F, et al. Illness perceptions and activity limitations in osteoarthritis of the knee: a case report intervention study. Man Ther. 2014;19(2):169–172.

- Becker SJ, Bot AG, Curley SE, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of neoprene vs thermoplast hand-based thumb spica splinting for trapeziometacarpal arthrosis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2013;21(5):668–675.

- Becker SJ, Makarawung DJ, Spit SA, et al. Disability in patients with trapeziometacarpal joint arthrosis: incidental versus presenting diagnosis. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(10):2009–2015 e8.

- Frouzakis R, Herren DB, Marks M. Evaluation of expectations and expectation fulfillment in patients treated for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(3):483–490.

- Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, et al. Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(4):575–587.

- Marks M, Audige L, Herren DB, et al. Measurement properties of the German Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire in patients with trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(2):245–252.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621.

- Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:86–95.

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532.

- Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, et al. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med. 2000;23(4):351–365.

- Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, et al. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the pain catastrophizing scale. J Behav Med. 1997;20(6):589–605.

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–637.

- Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, et al. The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16.

- Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Psychol Health. 2015;30(11):1361–1385.

- de Raaij EJ, Schroder C, Maissan FJ, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire-Dutch Language Version. Man Ther. 2012;17(4):330–335.

- Hallegraeff JM, van der Schans CP, Krijnen WP, et al. Measurement of acute nonspecific low back pain perception in primary care physical therapy: reliability and validity of the brief illness perception questionnaire. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):53.

- Timmermans I, Versteeg H, Meine M, et al. Illness perceptions in patients with heart failure and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: dimensional structure, validity, and correlates of the brief illness perception questionnaire in Dutch, French and German patients. J Psychosom Res. 2017;97:1–8.

- Eaton RG, Glickel SZ. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3(4):455–471.

- Dela Rosa TL, Vance MC, Stern PJ. Radiographic optimization of the Eaton classification. J Hand Surg Br. 2004;29(2):173–177.

- Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Boston, Mass.; [London]: Houghton Mifflin; [Hi Marketing] (distributor); 2003; Available from: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/50716608.html.

- Visser AW, Boyesen P, Haugen IK, et al. Radiographic scoring methods in hand osteoarthritis – a systematic literature search and descriptive review. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2014;22(10):1710–1723.

- Haugen IK, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Boyesen P, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between radiographic features and measures of pain and physical function in hand osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2013;21(9):1191–1198.

- Hoffler CE 2nd, Matzon JL, Lutsky KF, et al. Radiographic stage does not correlate with symptom severity in thumb Basilar Joint Osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(12):778–782.

- Kroon FPB, van Beest S, Ermurat S, et al. In thumb base osteoarthritis structural damage is more strongly associated with pain than synovitis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2018;26(9):1196–1202.

- Sonne-Holm S, Jacobsen S. Osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint: a study of radiology and clinical epidemiology. Results from the Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2006;14(5):496–500.

- Murphy SL, Lyden AK, Phillips K, et al. Association between pain, radiographic severity, and centrally-mediated symptoms in women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(11):1543–1549.

- Hill S, Dziedzic K, Thomas E, et al. The illness perceptions associated with health and behavioural outcomes in people with musculoskeletal hand problems: findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(6):944–951.