Abstract

Purpose

To explore the experiences of persons with physical disabilities accessing and using rehabilitation services in Sierra Leone.

Materials and methods

Interviews of 38 individuals with differing physical disabilities in three locations across Sierra Leone. An inductive approach was applied, and qualitative content analysis used.

Results

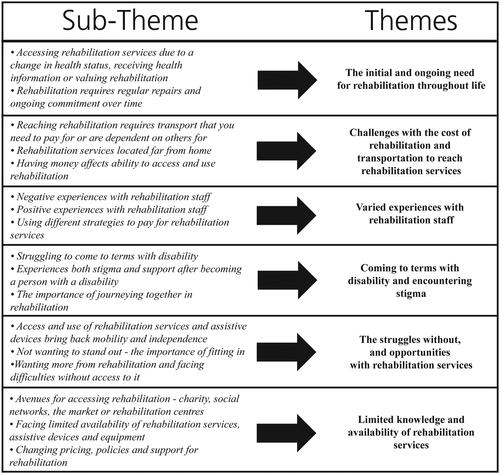

Participants faced several barriers to accessing and using rehabilitation services. Six themes emerged: The initial and ongoing need for rehabilitation throughout life; challenges with the cost of rehabilitation and transportation to reach rehabilitation services; varied experiences with rehabilitation staff; coming to terms with disability and encountering stigma; the struggles without and opportunities with rehabilitation services; and limited knowledge and availability of rehabilitation services.

Conclusions

There is a continued need to address the barriers associated with the affordability of rehabilitation through the financing of rehabilitation and transportation and exploring low-cost care delivery models. Rehabilitation services, assistive devices, and materials need to be available in existing rehabilitation centres. A national priority list is recommended to improve the availability and coordination of rehabilitation services. Improved knowledge about disability and rehabilitation services in the wider community is needed. Addressing discriminatory health beliefs and the stigma affecting people with disabilities through community interventions and health promotion is recommended.

Financing for rehabilitation, transportation to services and low-cost delivery models of care areneeded to reduce financial barriers and increase affordability of access and use.

Community interventions and health promotion can provide information about the utility and availability of rehabilitation services, while addressing health beliefs and stigma towards persons with disabilities.

The availability of both rehabilitation services and information, that is relevant and accessible is required to facilitate improved access and use of rehabilitation services.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Sierra Leone has a population of 7.6 million, is one of the poorest countries in the world, and is ranked 184 of 189 on the Human Development Index [Citation1]. More than 60% of people live under the poverty line on less than USD 1.35 per day [Citation2]. The civil war and the Ebola crisis, in combination with poverty, have weakened the healthcare system, leading to low vaccination rates, high levels of disease, and limited capacity to treat injuries [Citation3]. The reported disability prevalence in Sierra Leone is 1.3% [Citation3]. However, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that disability prevalence is 15% of any given population [Citation4], so it is likely that the disability prevalence is higher than the reported figure. The most prevalent physical disabilities are visual impairment (28%), poliomyelitis (22%), and physical disability due to war injury (9%). As disability is both a cause and consequence of poverty [Citation5], increasing access to and use of rehabilitation is key to breaking the poverty cycle and achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere” [Citation6].

Until 2009, Humanity and Inclusion (HI) (operating as Handicap International in Sierra, Leone) was the primary provider of rehabilitation services and assistive devices. In 2013, HI completed its gradual and planned handover of rehabilitation services to the government [Citation7]. As of 2020 the government runs four rehabilitation centres within the central referral hospitals that are situated in Makeni, Kono, Bo and Freetown that provide both physiotherapy and prosthetics and orthotic services. In addition, there are standalone physiotherapy departments in Connaught Hospital in Freetown, and in Kenema. Because rehabilitation is low-priority and lacks funding, only limited materials are available for the manufacture and supply of assistive devices. Similarly to other low-middle income countries, there is a severe shortage of trained rehabilitation staff such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, orthotists and prosthetists [Citation8]. As of 2019 there were only four bachelor-trained physiotherapists in Sierra Leone [Citation7]; 2019 email from Ishmaila Kebbi National Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Programme). In 2011, the government established a Persons with Disability Act and signed onto the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which calls for signatories to “organize, strengthen and extend” the availability of rehabilitation services [Citation9]. However, many components of these laws and regulations are yet to be implemented due to the low prioritisation of rehabilitation, and limited funding and materials to produce or supply assistive devices [Citation10–13].

Rehabilitation aims to reduce or eliminate barriers which inhibit full function, participation and inclusion in everyday life for persons with disabilities [Citation14]. Disability is an overarching term for “impairments, activity limitations and participation restriction”; however, it is not only a physical experience but influenced by the environmental, economic, social and cultural context in which people live [Citation15]. This study’s focus is on the access to and use of rehabilitation services including therapies such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy, as well as prosthetic and orthotic services which provide basic therapy in the form of physical exercises or the provision of assistive devices such as wheelchairs, crutches, prosthesis, orthosis, canes or braille technology [Citation4]. One study of Southern African countries estimated that only 26-55% of people received the medical rehabilitation they needed, and only 17-33% received the assistive devices required [Citation16]. While the utility of rehabilitation is known, access remains largely unmet, particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) where 80% of people with disabilities live [Citation4,Citation17].

Existing literature on access to health care services including rehabilitation has been conceptualised in various ways [Citation4,Citation18–20]. Broadly, “access” considers what factors enable or prevent someone from reaching and using services from supply and demand perspectives [Citation20]. The 5A’s of access is a framework [Citation20,Citation21] which takes into consideration how the approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability, and appropriateness of health care impacts access. The 5A’s can be used in policy and planning to consider ways to improve the accessibility and utility of health care services [Citation18,Citation20]. They are helpful in identifying barriers and developing strategies that may facilitate improved access and use of rehabilitation services when considering the experiences of persons with physical disabilities in Sierra Leone.

Existing studies on access to rehabilitation for persons with disability from countries such as Cameroon and India [Citation22], Nigeria [Citation23], Malaysia [Citation24], Namibia, Sudan, South Africa and Malawi [Citation25,Citation26], as well as systematic [Citation27] and scoping reviews [Citation28,Citation29] have found that common barriers to access and use of rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities in LMIC include: the lack of affordable services [Citation26,Citation29]; limited availability and low awareness of services [Citation22,Citation23,Citation25]; geographic and transportation barriers [Citation24,Citation26]; discrimination and a lack of trained staff and information [Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation29]. Studies from Sierra Leone have found persons with disabilities face challenges with the affordability [Citation30,Citation31], availability [Citation32], and quality [Citation33] of assistive devices, as well as facing stigma and marginalisation in society [Citation31,Citation32]. Further research is needed into the experience of persons with physical disabilities accessing and using rehabilitation services in order to understand the barriers and facilitators of access and use.

This study aims to explore the experiences of persons with physical disabilities accessing and using rehabilitation services in Sierra Leone by considering what factors facilitate or create barriers to access and use. Additionally, it hopes to highlight the need for increased efforts across the board to achieve access to rehabilitation for all, as called for by the “Rehabilitation 2030: call to action” [Citation14] and the CRPD.

Materials and methods

Study setting and sampling strategy

Study details were shared with leaders or management in all study locations in Freetown, Bo and Makeni. Participants were identified using purposive sampling and based on the convenience of being present at the National Rehabilitation Centre in Freetown, Bo Regional Rehabilitation Centre in Bo, the physiotherapy department at Connaught Hospital, and Milton Margai School for the Blind in Freetown. Sierra Leone Union on Disability Issues (SLUDI) provided details for Disability Persons Organisations (DPO), through which members were invited to participate in the study. Similarly, at the physiotherapy department at Emergency Hospital in Freetown, eligible individuals were invited to participate in the study. At the Rehabilitation Department at Makeni Government Hospital, the management of the rehabilitation centre acted as a gatekeeper by inviting people who met the inclusion criteria to participate.

To be eligible, participants had to be above the age of 18, with a physical disability including persons with lower-limb, upper-limb, or visual impairments. In total, 38 participants from the capital Freetown (n 18) and two regional centres - Makeni (n 16) and Bo (n 4) – and between 18-58 years old (mean 32 years) were included. Participants’ characteristics are presented in . Participants who had varying physical disabilities reflective of those most prevalent in Sierra Leone were captured in the study sample. Disabilities were the result of poliomyelitis, stroke, diabetes, dysmelia, war injuries, road traffic accidents and infections. Participants had been living with a disability for varying amounts of time - from birth to under one year.

Table 1. Information on participant (N = 38) characteristics.

Procedures

The Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee provided ethics approval as part of a larger study looking at access to health care and rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities. Interviews took place from February to March 2019. An interview guide was developed, with seven main questions focussed on understanding participants’ experiences concerning availability, affordability, quality, appropriateness and knowledge of accessing both healthcare and rehabilitation services. Questions such as “Can you tell me about a time you accessed rehabilitation services?”, “What motivated you to seek rehabilitation services?” or “How do you normally pay for your rehabilitation treatments?” were asked. To encourage participants to share their own experiences, main questions were followed by a series of suggestive probes such as “What are some of the things that make it easier for you to access the rehabilitation services?” or “How do you feel about the cost of rehabilitation services and devices?”.

Participants were informed about the study through an information letter in English, the official language of Sierra Leone, or Krio, which is the most widely spoken native language. Where necessary, it was read aloud in a language they understood. Written and oral consent to participate was obtained [Citation34]. Two pilot interviews in English were conducted to ensure the cultural appropriateness and validity of questions [Citation35], following which, minor amendments such as changes to the question order were made. Pilot interviews were excluded from the analysis.

Interviews were conducted in a variety of private locations at hospitals, schools, rehabilitation centres, DPO facilities or participant homes. If participants had travelled, their transportation costs were reimbursed. Participants were informed that the interview could be conducted in English or with an interpreter in the language of their choice. Interviews were conducted by the authors and trained assistant data collectors in English (n 22) or with the aid of an interpreter in Krio (n 13) or Temne (n 3). The decision for the interviews to be conducted in English with the aid of interpreters was to increase dependability [Citation36] and consistency in the questioning route across interviews conducted in different languages. In total five interpreters were used across the interview sites due to the distance between locations, and different languages. Interviews ranged between 29-105 min in length (mean 44 min). After interviews were completed, participants were informed they would receive a small financial token of appreciation for their participation.

Data analysis

To achieve trustworthiness, established steps of qualitative content analysis were followed [Citation34–36]. Interviews were transcribed in English by the author JA and Katherina Dihm while identifying content areas of “health” and “rehabilitation”. Once interviews were transcribed, interpreters cross-checked sections of the English transcripts to ensure accurate interpretation and transcription of participants’ experiences from interviews conducted in Krio and Temne [Citation37]. For this study, only data related to “rehabilitation” was included. The author JA divided transcripts into meaning units and then created condensed meaning units, to which codes were applied on a manifest level (see ). Codes were sorted into sub-themes and themes based on similarities and differences in the data, and emerging latent meaning (see ) [Citation36]. The themes were discussed and reviewed by the author LM, and then compared to the codes and the original interview text to ensure that all relevant data was included. Quotations that amplified the meaning of themes were selected and minor grammatical changes were made [Citation38,Citation39].

Table 2. Example of the data analysis process.

Results

The analysis resulted in six themes which are presented in below.

The initial and ongoing need for rehabilitation throughout life

For participants who became disabled later in life, the initial decision to access rehabilitation services was linked to a change in health status, and they were often referred to rehabilitation through the health care system or family. By contrast, the motivation for participants with dysmelia or childhood disabilities often occurred after receiving information about rehabilitation through health promotion messaging or from other persons with disabilities who had accessed services. However, many participants did not know or had limited knowledge about the availability or utility of rehabilitation services and the role that these could play in their everyday life.

I always have my earphones in listening to the radio, and mingling with so many stakeholders, that gives me information like ‘something is here in this country for the disabled like wheelchairs.’ I will also find out through the church. When I get this information, I will also share it so we can come together and go there. (Participant 21, poliomyelitis)

Access to rehabilitation was re-occurring and ongoing throughout life. Participants expressed their need to regularly repair and replace assistive devices. While many participants who had been using their devices for many years knew how to repair their wheelchair, personal energy transportation (PETs) or crutches themselves, those with less experience had limited knowledge and were more reliant on rehabilitation services for repairs. However, all participants using assistive devices expressed their ongoing need for access to rehabilitation services for replacements. Accessing services such as physiotherapy was not just a one-off experience; rather, it was ongoing and often intensive. For instance, learning how to walk again or stroke recovery required an almost-daily commitment ranging from three months to over a year.

For 8 months I have been coming to rehabilitation. It’s taken a lot of rehabilitation exercises. I spend 2-3 hours here every day. (Participant 9, stroke)

Challenges with the cost of rehabilitation and transportation to reach rehabilitation services

The decisions to seek rehabilitation, to repair devices, or to continue ongoing treatment were determined by a participant’s ability to pay for rehabilitation rather than their need. Participants delayed repairs, stopped treatment, or were unable to pay for necessary services or assistive devices as a result of financial barriers. Participants shared experiences of using different strategies to pay for rehabilitation services, such as being dependent on family and social networks; begging; taking loans or using savings. Participants often used a combination of these different strategies to be able to afford their required rehabilitation however this was not always possible. Participants expressed that rehabilitation was unaffordable.

As a government worker with a salary I can afford it, but some people find it extremely difficult. For me on a payroll yes, but what about someone who is not working? The living conditions in Sierra Leone are very hard. Some people I came here (rehabilitation centre) with, unfortunately, some of them stopped coming because they can’t afford it. For ordinary people who are not working it’s expensive. Last month there was a delay in the payment of the salaries so what happened to me was, unfortunately, I ran out of cash […]. So, I was unable to access the rehabilitation centre because of [having no] money. (Participant 9, stroke)

Additionally, the lack of support or money for transportation to rehabilitation services was one of the greatest barriers cited by participants as prohibiting access and use of rehabilitation services. Barriers in travelling to rehabilitation services manifest themselves in different ways such as lack of access to transport, lack of money or support to pay for transport, or the absence of appropriate transportation. Financial barriers limited the ability to pay for transport, which affected access particularly when support from others was unavailable. Some participants discussed the opportunity cost of reaching rehabilitation: having to choose between paying for transport or providing for their family. Participants expressed that having support from others or money for transport reduced financial barriers and made access easier.

What would make it easier is capital to pay. When I don’t have the money, I have to walk which makes it so difficult for me. Transportation to go there would make it easier (Participant 2, poliomyelitis)

For many, securing appropriate transportation was difficult due to rehabilitation services being located far from home or transportation being inappropriate for their physical needs. For example, many participants travelled great distances to access rehabilitation services as in their home town these were either unavailable or inappropriate. A difficulty experienced by many participants was the lack of appropriate transport such as having to use a motorbike to get to rehabilitation after an amputation or stroke. Because of the limited number of rehabilitation services, some participants attending physiotherapy, or a specialised blind school needed to live away from home for extended periods to access these services.

I can’t walk to the rehab centre, so I take a motorbike. This is difficult because I have to hold onto the rider with my hands. I can’t use my legs. I don’t have support. I need my crutches to get onto the bike. I can’t do it myself. (Participant 6, below-knee amputation)

Varied experiences with rehabilitation staff

Participants experienced a mixture of positive and negative encounters with staff. However, overwhelmingly experiences were positive: being treated with respect, attended to in a timely fashion, involved in their treatment and spoken to nicely. Some participants reported negative experiences such as being ignored, denied access to assistive devices and having to fight to be seen. Many participants attributed the varied nature of their experience to the individual staff members rather than the rehabilitation system as a whole. However, many participants explained how their experiences with staff and rehabilitation services were dependent on their ability to pay for services. A lack of money often resulted in negative encounters, whereas having money meant receiving services. Participants expressed frustration with this, citing their legal right to free health care services including rehabilitation according to the country’s Disability Act. Participants’ experiences with rehabilitation staff affected their willingness to return for ongoing treatment. Another negative experience shared by participants was being treated harshly or with distrust by rehabilitation staff when trying to replace broken assistive devices – often staff would accuse them of selling devices rather than the devices breaking.

You get treated normally if you have money. They will give you preferential treatment. If you don’t have money - forget it! Money answers everything. If you have money you get attention and respect. If you go with money and there is someone without money, they will treat you differently! (Participant 2, poliomyelitis)

Coming to terms with disability and facing stigma

Participants – particularly those who sustained a disability later in life – discussed struggling to come to terms with their disability, and - feeling scared, hopeless and angry at their situation. Some participants expressed facing stigma, being abandoned by family or feeling like they were burden– this often affected their ability or likelihood to seek rehabilitation. Experiencing support from community and family after becoming disabled was not only pivotal to accepting one’s disability but also increased the likelihood of seeking rehabilitation. Others experienced being supported and treated the same by family after acquiring their disability and during the rehabilitation process. One participant shared that when they began to lose their sight, their aunt wanted to hide them by sending them to the provinces. However, a change in the family’s perception of their disability led the family to support their access to rehabilitation.

With a disability in Africa, only your mother will be able to accept you. Nobody else. They look at you as a big burden. It’s a problem when you need to call them - for everything. They have their own life to live…it’s like you are a pain to them. (Participant 9, quadriplegic)

Relationships with other persons with similar disabilities were important in coming to terms with disability and seeking rehabilitation. Seeing others with similar conditions achieving improved functionality through rehabilitation or the use of assistive devices was the motivation for many participants to access and use rehabilitation.

Normally when I go there, I feel happy because there is interaction with staff and colleagues. This is encouraging. There are others with the same condition […] we give each other advice. I see other people in similar situations at the rehab centre walking. I had the conviction if I tried myself, I will be in the same position. (Participant 8, stroke)

Not wanting to stand out and the ability to fit in was both a facilitator and barrier to using assistive devices. Participants wanted to use assistive devices to be able to “bluff”. Participants with amputations desired prosthetics not only to regain functionality but also hide their amputation, whereas visually impaired participants expressed not wanting to use assistive devices such as white canes because it would highlight their disability.

I want to bluff because I am a human being just like you, so I want to be seen like everything is correct about me – even if they have cut my hand. (Participant 10, upper-limb amputation)

When you see this walking stick (white cane) in the street, especially in Sierra Leone they will think you are a street beggar. To avoid all that we don’t use a walking stick. Oh, I feel so embarrassed when people think I am a beggar. I will feel discouraged. I don’t want to be in that category… they will not even value you as a human being. They just think that you are nothing!! (Participant 18, visually impaired)

The struggles without and opportunities with rehabilitation services

Participants talked about how access to and use of rehabilitation and assistive devices brought back mobility and independence. Participants gave examples of being utterly dependent and needing to use their assistive devices to complete everyday tasks such as standing or going to the toilet, and for mobility to get to school or engage in income-generating activities. Using mobility devices gave participants greater independence and they expressed feeling stronger and healthier. Participants doing physiotherapy after stroke or injury regained movement and mobility. For the visually impaired, rehabilitation taught them to adapt to vision loss, enabled them to continue their education and restored confidence. Participants without access to rehabilitation services or devices wanted access in order to improve mobility, prevent injury and regain independence.

Without a wheelchair, I would prefer to die. I can’t go anywhere or do anything without it. The wheelchair is part of me now. (Participant 5, poliomyelitis)

While participants were generally happy and satisfied with rehabilitation, they expressed wanting more access to rehabilitation and faced difficulties without access. Participants experienced pain, inappropriate physiotherapy treatment, or access to poor quality or old assistive devices. Another limitation expressed was being unable to use their assistive devices in certain environments or on types of transportation. Life without access to rehabilitation services was described as a state of dependency on others for basic tasks like going to the bathroom or crossing the road. Participants with severe disabilities were utterly reliant on access to rehabilitation for all of their needs. When they were unable to access a rehabilitation service such as physiotherapy, they experienced a worsening of their condition.

I can do nothing by myself unless I have assistance […] Sometimes I am stuck up, I can’t breathe. If I go like one or two weeks without doing the stretching… I struggle with my breath. So, I have to do it again, and again, and again. (Participant 9, quadriplegic)

Several participants spoke about losing their jobs or no longer being able to work after becoming disabled. Especially for participants who sustained their disability later in life, returning to work was one of their primary motivations for wanting rehabilitation. However, none shared experiences of receiving any tailored rehabilitation assistance to return to work. For some participants accessing rehabilitation meant they felt they were now in a position where they were able to work but struggled to find employment. Other participants did not have the capital to restart their business due to out-of-pocket payments for rehabilitation.

I used to work at the district office as a typist. They left me. They haven’t asked me to come back to work since my stroke. I went there to ask for work, but they said there were no vacancies. I would like to work again. I could manage. (Participant 8, stroke)

Limited knowledge and availability of rehabilitation services

Participants’ experiences of accessing rehabilitation services were often characterised as inconsistent and unreliable. Participants experienced that pricing, policies and support to access and use rehabilitation services frequently changed. Many participants demonstrated a lack of knowledge about the current providers and policies surrounding rehabilitation. Some participants noted the withdrawal of NGOs and handover of rehabilitation services to the government, however there were different and contradictory understandings of this. Some participants thought services were currently free, while others said they were now being asked to pay for rehabilitation. Some believe the handover had resulted in limited and irregular financial support for rehabilitation services where costs were dependent on leadership. Many participants expected the government to provide more assistance for rehabilitation services.

Previously we had organisations like Handicap International, but since the end of the war, a lot of NGOs have pulled out and gone to other places. So, it’s extremely difficult to get any assistance from anywhere. The whole financial burden rests on you the patient. (Participant 9, stroke)

Another challenge expressed was the limited availability of rehabilitation services, assistive devices and equipment. Participants discussed hearing about things such as physiotherapy equipment or assistive devices for visually impaired which are used elsewhere in the world but unavailable in Sierra Leone. Some participants experienced going to get assistive devices from rehabilitation centres only to discover they were unavailable or the materials to make them were lacking. In some cases, unavailability led to participants not being able to continue their rehabilitation or use needed devices. If participants had family overseas, they often relied on them to provide equipment for rehabilitation rather than accessing this locally.

In Freetown, I have been twice (to the rehabilitation centre), but I did not get the service yet. The first time I went there, the services, the equipment were not available; there were no crutches, no wheelchairs nor PETs or things. The second time I went there they had crutches and wheelchairs, but they were already allocated to old clients. (Participant 2, poliomyelitis)

The decision to seek rehabilitation services was influenced by the perceived importance or role of rehabilitation in recovery and everyday life. Some participants believed that only rehabilitation enables a full recovery, while others had limited knowledge about its availability and utility. Participants’ understanding and perceptions of rehabilitation and assistive devices affected their willingness to use them. For example, some participants were unsure of the suitability of assistive devices such as white canes in the context of Sierra Leone or feared becoming dependent on them, creating a barrier to their use.

Participants cited a range of differing avenues for accessing rehabilitation, such as through charity, social networks, the market or rehabilitation centre. The majority of participants described being reliant on NGOs or their DPO membership in order to receive free rehabilitation services such as wheelchairs or physiotherapy. Many referenced receiving assistance from “white people”. Some participants experienced strangers assisting them out of what they perceived to be pity. Sharing or gifting assistive devices such as crutches or voice recorders between persons with disabilities was common, while for other participants the primary method of getting assistive devices was to purchase them from the market or from other people with disabilities. Particularly for participants requiring custom-made devices such as callipers, rehabilitation services were sought from rehabilitation centres.

The wheelchair was given to me by Handicap International when I returned to Freetown. It was for free. It was a white in colour that gave it to me. (Participant 4, poliomyelitis)

Discussion

The findings of this study aligned with Levesque, Harris and Russel [Citation20] conceptualisation of access to health care that understands access and use to be driven by a combination of supply and demand side factors. With a focus on the perspectives of users and intended users of rehabilitation services in Sierra Leone, this study found that participants faced several barriers when accessing and using rehabilitation services. The primary barriers were the financial cost related to transportation to reach rehabilitation services and the cost of the rehabilitation services and assistive devices themselves, the limited availability of services and information about rehabilitation, and societal attitudes and stigma towards persons with disability. Addressing these barriers is vital to improving access to and use of rehabilitation services in Sierra Leone.

Addressing barriers to affordability, access, and availability of rehabilitation

The cost of rehabilitation services was one of the key barriers expressed affecting access and use – which were compounded by the re-occurring and ongoing need for rehabilitation. This aligns with the concept of “Affordability” and the “Ability to Pay” being key determinants of access [Citation20]. This result reflects findings from other studies in South Africa, Rwanda, Tanzania [Citation40,Citation41], Malaysia [Citation24], and a systematic review [Citation42] looking at the experience of stroke patients and persons with disabilities in LMICs, which have shown that out-of-pocket payments create a significant barrier to access to rehabilitation services. Magnusson et al. [Citation33] found in Sierra Leone that 45% of orthotic and prosthetic users could not afford or experienced challenges paying for rehabilitation. Whereas in Botswana and Swaziland about half of the persons with disabilities had access to assistive devices and the likelihood of access was highest for those who had mobility limitations [Citation43]. This study, like Magnusson et al. [Citation33], found that issues with the affordability of rehabilitation services not only influenced access but the experience of use, further highlighting the importance of improving the affordability of rehabilitation in Sierra Leone. Similarly, participants experienced challenges travelling to and paying for transportation to reach rehabilitation services. This aligns with other studies in LMICs which found that the accessibility of health services including rehabilitation is a crucial determinant in the access and use of services [Citation24,Citation27,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45]. In a systematic review [Citation27] found that issues with transport, affordability, knowledge and attitudes where cited as barriers in 22 of the 77 evaluated papers. They found that these barriers while not exclusive to people with disabilities were often compounded due to their disability. These barriers are similar to those found in this study of the experiences of persons with physical disabilities in Sierra Leone accessing and using rehabilitation. Additionally, a literature review looking at rural transport and poverty in LMICs [Citation46] and a case study on mobility and health care in Nepal [Citation47] highlight the importance of addressing transportation barriers as key to improving access to health care services, particularly for those living in poverty [Citation46–48]. Given the high poverty rates in Sierra Leone [Citation2] and challenges with the affordability of rehabilitation, service delivery programs need to include financing for transportation to rehabilitation and the repairs and replacement of assistive devices. Strengthening the affordability of rehabilitation services is crucial to improving access to rehabilitation [Citation20], ratifying the CRPD, and implementing the Global Disability Action Plan and Rehabilitation 2030 in Sierra Leone. This will help ensure the sustainability and the ongoing ability of persons with disabilities to access and use rehabilitation services that are required.

In Malaysia [Citation24] and India [Citation42], there have been trials to reduce the financial burdens of rehabilitation for stroke patients through adjusting the care delivery model by promoting family-based rehabilitation that is supported by trained rehabilitation professionals. While Trani et al. [Citation10] found in Sierra Leone that most persons with disabilities believe that they can get support from family, research [Citation7,Citation31,Citation49,Citation50] has also highlighted the stigma and negative attitudes towards persons with disabilities from family and society. Therefore, the appropriateness [Citation20] of family-based rehabilitation as an approach to improve access to rehabilitation requires further exploration in the context of Sierra Leone.

Participants also experienced unavailability of rehabilitation, and particularly of assistive devices. This coincides with the results of a previous study from Sierra Leone [Citation32], a systematic and scoping review regarding access to rehabilitation [Citation27,Citation28] that found that limited availability of rehabilitation services and assistive devices affected rates of use. To facilitate increased use, rehabilitation devices and materials must be available so that existing rehabilitation services can operate effectively [Citation20]. It is recommended that the WHO Priority Assistive Products List [Citation51] be used to develop a national assistive products list to ensure the most essential products are available. Stakeholders could use this list as a tool to prioritise financing of assistive devices and materials, and also to oversee rehabilitation services provided by NGOs and charities to ensure balanced availability. Additionally, accurate data on the number of persons with disabilities and types of disabilities is needed for planning rehabilitation services if there is to be sufficient availability of rehabilitation services within the health care system in Sierra Leone.

Addressing knowledge gaps, attitudinal barriers and stigma towards rehabilitation and persons with disability

“Acceptability of access” considers attitudes and expectations towards services based on social-cultural norms and their influence on an individuals’ health-seeking behaviour [Citation20]. This study found that individual, community and family support were important facilitators not only in coming to terms with a disability but also in the decision to seek rehabilitation and use assistive devices. In the absence of support, and encountering stigma, participants experienced challenges accessing rehabilitation services. Similarly, studies in Africa, Asia and the Middle East found that attitudinal barriers and stigma towards persons with a disability threatened seeking, accessing and using rehabilitation services [Citation24,Citation29,Citation40,Citation41,Citation47]. Existing literature from Sierra Leone emphasises the stigma and discrimination faced daily by people with disabilities [Citation7,Citation31,Citation49,Citation50]. The findings of this study further highlight the importance of addressing underlying health beliefs and stigma due to the influence these have on the perceived acceptability of rehabilitation services [Citation20].

Through addressing societal stigma and attitudinal barriers, health promotion can increase knowledge about the availability and utility of rehabilitation services, increasing their overall approachability and heightening support for the access and use of rehabilitation services. The WHO has long recommended community-based rehabilitation (CBR) to improve quality of life, participation and empowerment of persons with disability [Citation52]. However, in Sierra Leone, Trani et al. [Citation53] found that in existing CBR programs there was higher engagement from non-disabled persons than those with disabilities. Further research on how to effectively engage both the wider community and persons with physical disabilities through community engagement activities is needed if they are to be effective in addressing stigma and health beliefs.

Limitations of this study include the varied depth of the content related to rehabilitation, and the length of interviews. Additionally, individuals with cognitive and hearing impairments were outside the scope of this study. Rural participants were primarily recruited from regional centres, and future studies may try to sample participants from more remote areas. Another limitation was that despite the researchers meeting a number of people in the deaf community through SLUDI, deaf people were not represented in the study sample because sign language interpreters were not found. This reflects the short data collection period as well as the general lack of sign language interpreters in country. Furthermore, using an interpreter in cross-language research influences the overall trustworthiness and credibility of the study [Citation37]. Previous research in Sierra Leone demonstrated that local words for disability are often stigmatising [Citation50]. To maintain the trustworthiness and credibility of the research, it was therefore essential to work with interpreters who were sensitive to issues faced by people with disabilities. This was achieved by working with interpreters who were recommended based on their prior experience working with the subject matter [Citation37].

Conclusions

There is a continued need to address the barriers associated with the affordability of rehabilitation services through strategies such as continued financing for rehabilitation services and transportation, and the exploration of low-cost delivery of care models. Rehabilitation services, assistive devices and materials need to be available in existing rehabilitation centres. Developing a national assistive products list is recommended to improve availability and coordination of rehabilitation services in order to facilitate greater access and use of rehabilitation services including assistive devices. Improved knowledge about disability and the role of rehabilitation services is needed for persons with physical disabilities and the wider community. Community interventions and health promotion could be used to address discriminatory health beliefs and stigma affecting people with disabilities. Policymakers and key stakeholders in rehabilitation must ensure that rehabilitation services are affordable, accessible, available and acceptable in the context of Sierra Leone. This essential if persons with disabilities are to be afforded their basic human rights, the CRPD and Rehabilitation 2030 are to be ratified, and the SDGs achieved.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Katharina Dihm's assistance in the development of this project, data collection, and constant support and friendship. Also, to Marie-Cécile Tournier, Pauline Ducos and Mariana Martinez of Humanity and Inclusion – Sierra Leone which provided logistic support, advise and warmly welcomed us and Uta Prel from Headquarters. We also would like to acknowledge the staff at the following rehabilitation and training centres and organizations for their help with participant recruitment for interviews; Ismaila Kebbie and Emily Amara at the National Rehabilitation Centre at Freetown, Musa Mansaray at Bo Regional Rehabilitation Centre; Bambino Suma at Rehabilitation Department, Makeni Government Hospital; the physiotherapy department at Connaught Hospital and Emergency Hospital; and Salieu Turay from Milton Margai School for the Blind in Freetown, and Santigie Kargbo from Sierra Leone Union on Disability Issues. A big thank you to Hannah Yeahon Sandy and our other interpreters for assisting with interpretation and translation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data used for this paper is only be available by a reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- The United Nations. Human development report - Sierra Leone [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 14]. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/SLE

- United Nations Development Program. About Sierra Leone | UNDP in Sierra Leone [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.sl.undp.org/content/sierraleone/en/home/countryinfo.html

- Kabia F, Tarawally U. Sierra Leone 2015 population and housing census: thematic report on disability [Internet]. Freetown; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 28]. p. 62. Available from: https://sierraleone.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Disability%20Report.pdf

- World Health Organisation. World report on disability [Internet]. Geneva; 2011 [cited 2019 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/

- Groce N, Kett M, Lang R, et al. Disability and poverty: the need for a more nuanced understanding of implications for development policy and practice. Third World Q. 2011;32(8):1493–1513.

- The United Nations. About the Sustainable Development Goals - United Nations Sustainable Development [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Humanity and Incusion. Operational strategy 2018-2020 Mano River program. Freetown; 2018.

- World Health Organization. WHO | Rehabilitation [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2019 May 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/rehabilitation/en/

- The United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2019 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/convtexte.htm

- Trani J-F, Browne J, Kett M, et al. Access to health care, reproductive health and disability: A large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(10):1477–1489.

- Kett M. Disability and poverty in post-conflict countries. In: Barron T, Nucube, Jabulani M, editors. Poverty and Disability. London: Leonard Cheshire Foundation; 2010.

- Zampaglione G, Ovadiya M. Escaping stigma and neglect: people with disabilities in Sierra Leone [Internet]. Washington DC; 2009 [cited 2019 Jan 15]. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/180911468299196149/Escaping-stigma-and-neglect-people-with-disabilities-in-Sierra-Leone

- Stewart BT, Kushner AL, Kamara TB, et al. Backlog and burden of fractures in Sierra Leone and Nepal: results from nationwide cluster randomized, population-based surveys. Int J Surg. 2016;33:49–54.

- World Health Organisation. Rehabilitation 2030 a call for action [Internet]. Geneva; 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/care/rehab-2030/en/

- World Health Organisation. WHO | Disabilities [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2019 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/topics/disabilities/en/

- World Health Organisation. WHO guidelines on health-related rehabiliation [Internet]. Geneva; 2012 [cited 2019 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/care/rehabilitation_guidelines_concept.pdf

- Kamenov K, Mills JA, Chatterji S, et al. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;41(10):1227–1237.

- O’Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(12):2820–2834.

- Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, et al. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1136(1):161–171.

- Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18.

- Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. [Internet]. 1981;19(2):127–140.

- Mactaggart I, Kuper H, Murthy GVS, et al. Assessing health and rehabilitation needs of people with disabilities in Cameroon and India. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(18):1757–1764.

- Igwesi-Chidobe C. Obstacles to obtaining optimal physiotherapy services in a rural community in Southeastern Nigeria. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012:909675.

- Mohd Nordin NA, Aziz NAA, Abdul Aziz AF, et al. Exploring views on long term rehabilitation for people with stroke in a developing country: findings from focus group discussions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):118.

- Eide AH, Mannan H, Khogali M, et al. Perceived barriers for accessing health services among individuals with disability in four african countries. Federici S, editor. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125915.

- Munthali AC, Swartz L, Mannan H, et al. This one will delay us”: barriers to accessing health care services among persons with disabilities in Malawi. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(6):683–690.

- Bright T, Wallace S, Kuper H. A systematic review of access to rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. IJERPH. 2018;15(10):2165.

- Kamenov K, Mills J-A, Chatterji S, et al. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;41(10):1227–1237.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Viriyathorn S, et al. Improving access to assistive technologies: challenges and solutions in low- and middle-income countries. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7(2):84.

- Trani J, Browne JL, Groce N, et al. Disability in and around urban areas of Sierra Leone [Internet]. Campbell Systematic Reviews. London; 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320757193_Disability_in_and_Around_Urban_Areas_of_Sierra_Leone

- Andregård E, Magnusson L. Experiences of attitudes in Sierra Leone from the perspective of people with poliomyelitis and amputations using orthotics and prosthetics. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(26):2619–2625.

- Magnusson L, Ahlström G. Experiences of providing prosthetic and orthotic services in Sierra Leone – the local staff’s perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2111–2118.

- Magnusson L, Ramstrand N, Fransson EI, et al. Mobility and satisfaction with lower-limb prostheses and orthoses among users in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(5):438–446.

- Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14.

- Tolley E, Ulin P, Mack N, et al. Qualitative methods in public health: a field guide for applied research. 2nd ed. San Fancisco: Wiley; 2016.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Squires A. Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: a research review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):277–287.

- Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Winkvist A, et al. Qualitative methodology for international public health. 2nd ed. Umeå: Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine; 2007.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. InterViews: learning the craft of qualiative research interviews. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc; 2015.

- Rhoda A, Cunningham N, Azaria S, et al. Provision of inpatient rehabilitation and challenges experienced with participation post discharge: quantitative and qualitative inquiry of African stroke patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–9.

- Hussey M, MacLachlan M, Mji G. Barriers to the implementation of the health and rehabilitation articles of the united nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities in South Africa. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;6(4):207–218.

- Pandian JD, William AG, Kate MP, et al. Strategies to improve stroke care services in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;49(1-2):45–61.

- Matter RA, Eide AH. Access to assistive technology in two Southern African countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–10.

- Abdi K, Arab M, Rashidian A, et al. Exploring barriers of the health system to rehabilitation services for people with disabilities in Iran: a qualitative study. Electron Physician. 2015;7(7):1476–1485.

- Mlenzana NB, Frantz JM, Rhoda AJ, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of rehabilitation services for people with physical disabilities: a systematic review. African J Disabil. 2013;2(1):1–6.

- Hine J, Starkey P. Poverty and sustainable transport - how transport affects poor people with policy implications for poverty reduction: a literature review. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Apr 24]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1767Poverty%20and%20sustainable%20transport.pdf

- Molesworth K. Mobility and health: the impact transport provision on direct and proximate determinates of access to health services [Internet]. Basel, Switzerland; 2006. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263945722_The_impact_of_transport_provision_on_direct_and_proximate_determinants_of_access_to_health_services

- Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):976–993.

- Magnusson L, Bickenbach J. Access to human rights for persons using prosthetic and orthotic assistive devices in Sierra Leone. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;42(8):1–8.

- Berghs M, Dos S-ZM. A comparative analysis: everyday experiences of disability in Sierra Leone. Afr Today. [Internet]. 2011;58(2):19–40.

- World Health Organisation. WHO | Priority Assistive Products List (APL) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/phi/implementation/assistive_technology/global_survey-apl/en/

- World Health Organisation. WHO | Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/cbr/en/

- Trani J, Bah O, Bailey N, et al. Disability in and around urban areas of Sierra Leone. UCL, London; 2017.