Abstract

Purpose

Sleep problems are common in children with cerebral palsy (CP) and have a large impact on child health and family functioning. This qualitative study aimed to explore parental perspectives regarding the care for sleep of their young child (age 1–8 years) with CP.

Materials and methods

Individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted with eighteen parents of a child with CP (GMFCS levels I-V). Inductive thematic analysis of the data was performed within each of the three preidentified domains: 1) Current situation; 2) Concerns; 3) Needs.

Results

In total, sixteen themes were identified across the three domains. Within the families’ Current situation, parents expressed various issues concerning the care for sleep of their child both at night and during daytime, which are hampered by perceived deficiencies in healthcare, such as limited attention for sleep and lack of knowledge among health professionals. Themes within the Concerns and Needs domains encompassed experiences in the home environment relating to child, family and social aspects, while experiences in the healthcare setting included clinical practices and attitudes of healthcare professionals, as well as the broader organisation of care for sleep.

Conclusions

Parents face numerous challenges caring for their child’s sleep and the burden placed on families by sleep problems is underappreciated. In order to break the vicious circle of sleep problems and their disastrous consequences on the wellbeing of families, we need to wake up to parent-identified issues and shortcomings in healthcare. Care for sleep should be integrated into paediatric rehabilitation through routine inquiries, using a family-centered and multidisciplinary approach.

The heavy burden placed on families by sleep problems in children with cerebral palsy warrants acknowledgement in paediatric healthcare.

Sleep should be routinely addressed by clinicians during health assessments using a family-centered, and multidisciplinary approach.

Healthcare professionals ought to adopt a proactive, understanding, and non-judgmental attitude when addressing sleep problems.

Future research should focus on developing sleep intervention strategies that take into account the diverse parental concerns and needs unique to each family situation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a common cause of childhood disability worldwide [Citation1]. Between 23% and 46% of the children with CP are reported to experience sleep problems [Citation2–6]. These sleep problems range from difficulties in initiating and maintaining sleep, to sleep-wake transition disorders, excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep-related breathing disorders [Citation2,Citation3,Citation6]. Although the underlying causes of the sleep problems are not always clear, they may be related to (a combination of) comorbid physical and medical conditions that often accompany CP, such as spasticity, epilepsy, reflux, pain, a decreased ability to change body position at night, visual impairments, sensory sensitivity and behavioural problems [Citation7–13].

Sleep deficiency in childhood adversely affects health and development [Citation14]. Lower sleep quality is related to deficits in cognitive functioning and significantly impacts on school performance of both typically developing children and children with CP [Citation2,Citation15,Citation16]. In children with CP, sleep problems have been shown to increase the risk of impaired psychological health [Citation17], with insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness being associated with a lower quality of life [Citation18].

In addition to the negative implications for the child, sleep problems in children with CP can place a heavy burden on the family [Citation2,Citation5,Citation6]. Parents can become sleep deprived themselves as a result of their child requiring night-time attention [Citation5,Citation19,Citation20]. Increased caregiving demands at night have been associated with elevated parental stress and psychological exhaustion [Citation20–23]. As one study has shown, 40% of mothers of a child with CP experienced poor sleep quality, which in turn was associated with maternal depression [Citation13]. In the same study, 74% of parents reported impairments in daytime functioning because of their child’s sleep disorder [Citation13].

Clearly, sleep problems in children with CP and its consequences must be considered as a broader issue, concerning the entire family system [Citation6,Citation7,Citation24]. Understanding the caregiving experiences of parents and the challenges they face, are necessary to better support these families. Therefore, the objective of this qualitative study is to explore the care for sleep of children with CP from a parental perspective.

Methods

Study design and procedure

A qualitative, exploratory study was conducted using an inductive thematic analysis approach [Citation25,Citation26]. The research team consisted of researchers and healthcare professionals with varied backgrounds (i.e. paediatric rehabilitation, biomedical sciences, medicine and somnology), enabling us to take different interpretations of the data into account. The Medical Ethics Research Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands, granted the study exempt from the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (file number 19-066), and therefore no ethical approval was required.

Participants

Parents of children with CP were recruited via healthcare settings (rehabilitation centers and rehabilitation department of a children’s hospital) and parent organisations (CP Nederland and OuderInzicht) in the Netherlands, using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were parents of a child with CP classified as Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels I-V, and under the age of 16. As sleep varies greatly across childhood, we focused on early childhood after infancy, spanning the period between the age of 1 and 8 years. To increase the sample size, we also included parents of children older than 8 years, who were asked to reflect on the period of their child’s life between the age of 1 and 8 years. Exclusion criteria were not being able to understand or converse in Dutch. Parents were informed about the study by means of an information brochure, and were subsequently asked for permission by their treating physician (assistant) or therapist to be contacted by the researcher. Participation in the study was voluntary and all participants signed an informed consent form.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (RYH), and used for data collection. A topic guide (Supplementary Appendix 1) was developed based on existing literature and expert knowledge of the research team, and was structured to cover three domains that were set a priori: 1) Current situation; 2) Concerns; 3) Needs. Open-ended questions were used to gain insight into parent’s experiences regarding the care for their child’s sleep within these three domains, aiming to identify sleep-related issues in the families’ current situation, concerns parents may have regarding their child’s sleep, and how these may affect their family, as well as parental needs with regard to improving the care for their child’s sleep. Although the interviews were guided by pre-set topics, parents were allowed and encouraged to address topics and issues which they felt deserved receiving acknowledgement. Therefore, the term “care for sleep” could be freely interpreted by parents as any care related to the child’s sleep (problems), whether it be care provided by caregivers, parents, or nurses providing night care at home, or care delivered in paediatric clinical practice. Similarly, the phrasing “sleep problem” was not tied to any particular sleep disorder, but rather served as a term to describe sleep as problematic when parents perceived and reported it as such. Parents were given the choice to have the interview conducted by telephone or face-to-face at a location of their preference. The sample size was not determined before the start of the study, but followed the qualitative approach of data saturation: this was achieved when no new themes emerged during three consecutive interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission. To improve validity of the data and enhance credibility, a summary of the initial pair of interviews was shared with the corresponding participants for member-checking.

Data processing

Audio-taped interviews were transcribed verbatim. Final transcripts were cross-referenced against the audio tapes by an independent student-researcher to ensure accuracy. Personal details were removed from the transcripts and a unique numeric code was assigned to each interview transcript to ensure anonymity.

Data analysis

Data were coded independently by two researchers (RYH & OV) using MAXQDA (VERBI Software, version 2018.2). Inductive thematic analysis [Citation26] of the data was undertaken within each of the three preidentified domains. First, the transcribed texts were repeatedly read to become familiar with the narratives and to gain an initial understanding of the content. Next, the texts were broken down into fragments of meaningful units, which were labelled with codes. Codes were compared and discussed between researchers until consensus regarding content and interpretation was reached. Subsequently, interpretive coding took place, during which the codes with comparable meaning were clustered into categories, and subsequently grouped into subthemes. Finally, subthemes were further collapsed into overarching main themes within each of the three domains (Current situation, Concerns, Needs). Preliminary results were discussed with experts in the field of qualitative research and refined accordingly. To ensure credibility of the findings, the entire research team was involved throughout the process of data analysis. Organisation of categories and construction of (sub)themes within domains were decided upon through discussions until agreement was reached about the interpretation of the data. Quotations from the interviews are enclosed in the results section to illustrate our findings and verify interpretations.

Results

Participants

In total, eighteen parents (one parent per family) were interviewed. Interviews were between 33–74 min in duration. Four parents of children above the age of 8 were asked to reflect on the period of their child between the age of 1 and 8 years. Characteristics of participating parents and their child are summarised in .

Table 1. Characteristics of parents and their children.

Findings

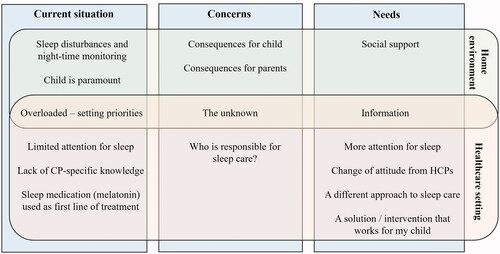

The findings of this qualitative study revealed that, regardless of the presence and extent of possible sleep problems, all parents expressed a range of concerns and needs with regard to the care for sleep of their child. Within each of the three domains set a priori (Current situation, Concerns, Needs) several themes and subthemes () were identified; across domains there seemed to be a clear separation between themes described within the families’ home environment versus those established within the healthcare setting. shows a representation of how identified themes map across domains and environmental settings. Themes are discussed below for each of the three domains, with illustrative quotes.

Figure 1. Representation of the identified themes mapped across the three domains (Current situation; Concerns; Needs) and environmental settings (Home environment; Healthcare setting).

Table 2. Current situation.

Table 3. Concerns.

Table 4. Needs.

Current situation

This domain encompasses descriptions of the current situation or context in which sleep problems manifest at home, and how sleep is currently addressed by healthcare professionals from a parental viewpoint. Six themes were identified ( and ).

Sleep disturbances and night-time monitoring

Parents gave detailed descriptions of the sleep disturbances their child experiences at night, which could range from waking up a few times per night to hardly getting any sleep. The child’s sleep problems were often accompanied or believed to be caused by co-morbid problems, such as breathing difficulties, epilepsy, reflux, or pain. These problems frequently required parents to be constantly alert and vigilant during the night:

“We are trained to hear the sound of her suffocating; it’s the sound that alerts you. And when she cries, you hear it of course. But there are moments that we think we don’t even notice. So we use camera and sound monitoring.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

As a consequence of night-time monitoring, many parents have to get out of bed multiple times per night. Some parents described this to be “normal”:

“In the beginning there were nights that I went out of bed, say 10 to 15 times. That was just quite normal.” (Parent of a 5-year-old child)

Child is paramount

For some parents the child’s sleep comes first before everything else, including their own sleep. Parents try to do whatever it takes to make sure that their child sleeps well, either to prevent the negative effects that poor sleep has on the family, or because they feel there is no other option. In contrast, other parents reported to “accept” the sleep problems of their child; instead of trying to do whatever it takes to fix the issue, they rather focus on coping with the current situation in the best possible way. For some, this simply meant ensuring that at least they themselves get enough sleep at night in order to be able to function the next day:

“Our criterion is not based on her being awake or not anymore. Our criterion is based on our ability to sleep. So, yes, she might be awake for hours, that is possible. It could be better perhaps, but we have tried many things. We still have the same sleep problems and the only thing we’ve done is to try and make sure we suffer as little as possible in our daily functioning. Ourselves.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Overloaded – setting priorities

Having a child with CP requires parents to provide and manage multidimensional health and care needs simultaneously. Sleep is only one of the many domains that requires attention. Not having enough time to manage everything demands parents to make choices and set priorities:

“This is one of those 400 action points on our list that we have to work on. It [sleep] is very important for her, just like learning how to communicate and being in a wheelchair, and when she’s ill, then that gets priority. So, there’s always something that keeps us awake.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Limited attention for sleep in healthcare

In describing the current healthcare of their child, the majority of parents stated that there is limited, if any, attention for sleep. Some parents reported never to have been asked about the topic sleep by their healthcare professional:

“No one ever really asks about it [sleep]” (Parent of a 2-year-old child)

Other experiences described hospital visits, where awareness around the importance of sleep and the (long term) consequences of impaired or disturbed sleep for the (sick) child was lacking:

“We were in the hospital for a while. And they had to inject her - whether it was her time to sleep or not. So she would be woken by a complete stranger. It gave her a bit of a mini trauma which would go on for weeks, and she’d be afraid to go to sleep.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Lack of CP-specific knowledge

A recurrent statement from parents was the healthcare professionals’ lack of knowledge about CP and a constant comparison of their child (with CP) to typically developing children. Receiving “generic” help or advice that is not tailored to their child with CP, brought along frustration and a feeling of being not taken seriously. This was the case in hospitals, but also in specialised sleep clinics:

“Then you get to an official sleep clinic, but they haven’t got a clue about children like XY. It’s all based on normal people. This is such a specific issue. So then they’d say: ‘Oh well…’ and they’d start to mess about with melatonin, but it has to do with so many different factors.” (Parent of an 11-year-old child, in retrospect)

Sleep medication (melatonin) is used as first line of treatment

As illustrated in the abovementioned quote, several parents reported that in current healthcare, sleep treatment is focussed on the use of pharmacological interventions. In their point of view, melatonin and sleep medication seem to be used as first line of treatment, despite the reported negative effects on the child’s wellbeing:

“What I think is a shame, is that the first solution is always prescribing medication. XY had sleep medication at one time and, ah, it was a disaster. She would wake terribly - we really thought it made her ill.” (Parent of a 15-year-old child, in retrospect)

Concerns

This domain describes the four main concerns that parents have and the challenges they face in caring for their child’s sleep (). Themes and sub-themes are presented in .

Consequences for the child

The main concerns expressed by parents were related to the consequences of sleep problems for the child, as well as for the parents. The consequences for the child highlighted three areas of concern. Firstly, parents expressed health concerns for their child, like getting sick more easily as a result of poor sleep. Others worried about their child’s wellbeing during the night. For example, statements were made about children suffering from pain caused by spasticity in their limbs, lying uncomfortably (e.g. from wearing night orthoses) or unknown reasons that keep them awake at night. The following quote from a mother illustrates the extent of her concerns:

“We really thought: if you have to live like this, it should be over, because you’re in such pain. And this happens in the middle of the night, she would wake up screaming and crying, and after an hour you still can’t get her to calm down and we would think ‘If you have to live like this, then, rather not at all…” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Secondly, parents mentioned concerns about poor sleep acting as a negative spiral, thereby impacting on everything else in their child’s life and development:

“It’s like a house of cards, if you lack sleep; it has an effect on all other areas.” (Parent of an 11-year-old child, in retrospect)

These statements indicate that parents consider sleep as a fundamental building block, necessary for their child to function properly.

Thirdly, concerns were expressed with regard to the child’s future. Parents worried about their child’s ability to sleep in the future in general, sleepovers, structure and routines. For various reasons, some children had developed a preferred sleeping position (usually on one specific side) which imposed future-related worries for this mother:

“I have been thinking about sleep as such - I’m worried about these severe spasms. He always wants to sleep in a specific position, on his side. And he can really tense up his legs, or he can be lying there totally relaxed. And then I sometimes think, when he gets older and gets more physical ailments, then he will not be able to sleep in a comfortable way anymore. I would worry how he would be able to sleep.” (Parent of a 7-year-old child)

Consequences for parents

In addition to consequences for the child, parents described concerns in terms of consequences for themselves. Comprehensive reports of the impact of sleep disturbances on many areas of family functioning were given by parents. The need for parental monitoring at night required them to be constantly alert for sounds, to check video/audio recordings, or to physically get out of bed multiple times per night. On top of that, the resulting deprived parental sleep led to adjustments in households, like rotating night ‘duties’ or deploying nurses that provide night care. All these consequences impacted greatly on families.

“We swap days and nights shifts and we recently had a week without any help at night. Well, we felt like dead! Now that we have help during the night, it is OK. But if I have one night without sleep, I think: ‘How did I do it?’. It’s just impossible, not real, and all you do is surviving, but you really can’t do it.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Another factor repeatedly reported to negatively affect daytime family functioning was their child’s excessive sleepiness or fatigue during the day, which according to parents was often a consequence of them not getting enough sleep at night:

“It [fatigue of the child] is a very limiting factor in your life. You really have to plan things. We can do one or two things a day, then it’s finished.” (Parent of a 7-year-old child)

Parents are struggling with their current situation and the consequences for the entire family, with some describing to have turned into “survival mode” in order to cope with the circumstances. As a result, concerns were expressed about having to keep up with this daunting and exhaustive situation that parents are in. This brought along uncertainties about their future and raised questions like: ‘When will we reach our limits of not being able to proceed any longer?’ - as this mother described:

“Perhaps it will change, in terms of sleep. But our main worry is: what will happen then? We are not thinking about respite care at all yet. But at some point, we may reach our limits, and then things will have to change.” (Parent of a 7-year-old child)

The unknown

In many cases, parents did not know the exact cause of their child’s sleep problem. This concern is enhanced by the fact that some children with CP cannot speak, making them unable to explain what is bothering them:

“It’s always so funny with a non-speaking child (sarcastically). It could be epilepsy, it could be constipation, it could be spasm or cramps, but it could also be a hairpin on her pillow that pricks in her ear, but she can’t tell us. And then she lies there, she’s strapped in one position and she can’t even turn herself around.” (Parent of an 11-year-old child, in retrospect)

Others described not knowing whether the origin of the sleep problems is related to their child’s developmental age, is inherent to their child’s natural characteristics/behaviour, or whether it directly results from their child’s brain damage:

“It’s so difficult. What is normal toddler behaviour? And what is XY? And what comes out of his CP?” (Parent of a 5-year-old child)

Responsibility

Parents repeatedly voiced concerns about the lack of clarity of responsibilities of healthcare professionals when it comes to care for sleep. From their point of view, nobody takes clear responsibility for the topic, as sleep does not “fit” under one discipline, but clearly is an integral part of their child’s health in general. Their uncertainty is accompanied by the fact that generally there are many professionals involved in their child’s healthcare, leaving parents unsure who to approach:

“I wouldn’t know. We talk to ten different parties. I have a physical therapist, a paediatrician, a school, a social worker, I have (…) Who do we ask? I wouldn’t even know who to ask…” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Needs

Six themes were identified as parental needs (). Themes and sub-themes are presented in .

Social support

Parents mentioned not feeling understood by the people around them:

“Our direct environment, they just do not understand. Because you cannot understand when you’re not in the middle of it.” (Parent of a 7-year-old child)

Since their friends and neighbours “do not have a child like theirs”, the adverse consequences of the child’s sleep problems, like deprived parental sleep, fatigue or forgetfulness during the day, are too often not appreciated by the social environment. As a result, this mother constantly needs to remind others of her impaired sleep and exhaustion:

“Then at some point you start to think: ‘I am so bone tired!’ And then I’ll explain again: ‘Hey guys, I’m so… I don’t sleep.’ And then they understand. But you have to keep at it, and it just goes on. It’s very invisible. It’s always something you need to indicate: ‘Gosh, I notice that I’m exhausted, I simply forget things, I haven’t registered.’” (Parent of an 11-year-old child, in retrospect)

Parents therefore expressed the need for social support, i.e. receiving understanding and acknowledgement from their environment.

Information

As many parents expressed their concern of not knowing the cause of their child’s sleep problem, there is a logical need for them to gain insight into the cause. In addition, understanding the consequences of sleep problems was marked important for parents to prepare themselves for what is coming. They expressed a need for objective, reliable information about sleep that is clustered in one place, and specifically aimed at children with CP.

Furthermore, there was a strong need for receiving advice about possibilities to improve sleep. This ranged from specific information about sleeping devices or orthotics, to general advice about healthy sleep practices, or tips from other parents of a child with CP. Some parents seemed afraid to miss out on potential important information that may benefit them and their child, if they are not informed about such matters:

“I believe that there are advices and tools out there that could be helpful, but I’m not aware of them. So it would be good if others can inform you or point them out to you.” (Parent of a 10-year-old child, in retrospect)

More attention for sleep in healthcare

A unanimous necessity that parents expressed was the need for sleep to receive more attention in healthcare. Parents indicated that they had never really been asked about sleep by their child’s rehabilitation physician, and that they would appreciate the topic being discussed routinely during check-ups.

“I believe that especially for children like XY it’s important to sleep well, so (…) it should be addressed” (Parent of a 2-year-old child)

Whilst participating in this research, a mother realised that she wished that healthcare professionals had asked her about her child’s sleep before:

“Talking about it, I realise that although I had a lot of questions about it [sleep], I couldn’t formulate them myself without people asking me first. It’s only when other people ask about it, that you think: ‘Oh, that’s strange indeed’. And now that we’re talking about it, I would have liked to hear more, and be questioned about it.” (Parent of a 4-year-old child)

According to parents, they often have to take the lead in bringing up issues concerning sleep. The majority indicated that they would like their healthcare professionals to take the initiative during consultations, and inquire with parents earlier.

“Very much at our own initiatives as parents. I would have liked the doctor to take initiatives and tell us or ask us about it. And start early, not when a parent is already deep in trouble, but before.” (Parent of a 15-year-old child, in retrospect)

Change of attitude from healthcare professionals

A different attitude from healthcare professionals was perceived as an important need by parents. Discussing the sleep problems that parents experience at home can be a sensitive topic that requires a coaching, understanding attitude from healthcare professionals, without being judgemental:

“Talking to parents, coaching, without judging. That’s the most important thing. Parents often feel pushed into a corner, or being judged that they don’t do enough. And we are vulnerable. I was less open. But when I realised I wasn’t being judged I became more open.” (Parent of a 15-year-old child, in retrospect)

A different approach to sleep care

A significant theme identified as parental need, is for the care for sleep to receive a different approach. Parents described current healthcare to be very child-centred, i.e. focused on the child alone. The majority expressed a clear need for their child’s healthcare to become more family-centred. This implies that parents would like healthcare professionals to consider their sleep and wellbeing in the context of their child’s sleep issues:

“I think we need to be asked more questions, and also aimed at the parents, like: ‘How is your sleep? How does that suffer from your child’s sleep?’ That doesn’t happen enough yet. That this is also taken into consideration. This is just as important as looking at the child. Not enough is done to see how parents are coping.” (Parent of a 7-year-old child)

Parents reported healthcare professionals to be too focussed on their own discipline alone. Only by taking into account a wider scope of view, by combining aspects of different disciplines, the child can be considered as a whole. This parent advocated a holistic approach could benefit finding a solution to her child’s sleep problem:

“I think we need to be more multi-disciplinary towards dealing with sleep problems. Because reflux might play a part … or other medical issues … sleeping position, cramps during the night. We do not look at the complete picture yet.” (Parent of a 15-year-old child, in retrospect)

In line with this holistic approach, parents view care for sleep to be the responsibility of every professional involved in their child’s care. As multiple disciplines are typically involved in the child’s healthcare, parents expressed the need for them to combine their knowledge and expertise as a way to approach sleep care:

“I always ask for a different attitude. We need to work together, look at the problem together. So the ‘sleep-doctor’, that’s what I’ll call him, and the rehabilitation services should work with us to solve the puzzle. Let’s solve this problem, with joint knowledge.” (Parent of an 11-year-old child, in retrospect)

Clearly, parents would like to turn the care for sleep into a team effort.

A solution/intervention that works for my child

Ultimately, parents want to find a solution or intervention that works for their child:

“I would appreciate it if someone comes to a solution.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Many parents reported to have undertaken actions to prevent or treat their child’s sleep problems, some of which were successful. Anecdotes shared by the parents made it clear that there are dozens of different types of interventions that could optimise sleep, but due to the heterogeneity of the sleep problems in children with CP, only certain interventions seem effective for certain children. According to parents, sleep interventions should be tailored to the child’s needs, parental needs, and home situation. Additionally, parents indicated lack of a clear overview of the possibilities and routes to follow when it comes to finding appropriate sleep interventions, and believe that clinicians should guide them in finding the solution they seek:

“They should know which route to follow to get help and where.” (Parent of a 6-year-old child)

Discussion

Achieving a good night’s sleep for both the child and the parents is important for health and wellbeing. In children with CP the prevalence of sleep problems is high and the resultant burden placed on families is underappreciated. Our qualitative study addressed parental perspectives on the care for sleep of children with CP, and identified various concerns and needs that warrant acknowledgement. Perceived shortcomings in current healthcare lead to under recognition of the challenges faced by parents in caring for their child’s sleep. This paper serves as a wake-up call echoing the parents’ voices to raise awareness about the importance of sleep in paediatric healthcare.

Similar to concerns of parents of children with physical disabilities [Citation23], parents in our study reported being concerned about their child’s safety and wellbeing at night, which often resulted in the need to monitor the child’s sleep at night. Additionally, long-term concerns about the negative consequences of poor sleep on the child’s general health along with worries about the child’s future sleep habits were frequently expressed. Secondary to the child, parents were concerned about adverse consequences for their own wellbeing. Increased caregiving demands at night were reported to lead to deprived parental sleep, extreme fatigue, and significantly impaired family functioning during daytime. In fact, coping with a child with sleep problems has been described as one of the main causes of parental stress in these families [Citation23,Citation27]. Our findings are in line with prior research on parents of children with physical disabilities who suffered from disrupted sleep, poor health and psychological exhaustion when their child had sleep problems [Citation5,Citation20,Citation23]. It may be clear that the harmful effects of sleep problems on family functioning should be considered of great concern, especially given the previously reported lower quality of life and decreased mental health in parents of children with CP [Citation13,Citation22,Citation28,Citation29]. This study complements previous findings by showing that sleep problems can further operate in a downward spiral, with exhausted parents who experience day-to-day hassles that can pile up and cause a stress overload, while others quietly contemplate respite care in view of reaching their limits. In order to break the vicious circle of sleep problems, it is crucial for sleep care to be acknowledged within paediatric healthcare in a family-centered manner.

Despite the high prevalence of sleep problems in children with CP, they are still underrecognised in neurorehabilitation [Citation24]. According to parents in our study, clinicians caring for their child rarely inquire about sleep and lack knowledge to detect sleep problems. This is supported by studies that have shown significant gaps in both knowledge and clinical practices regarding paediatric sleep disorders among physicians, paediatricians and child neuropsychiatrists [Citation30–32], yet little is described in the context of paediatric rehabilitation. From the experiences shared by parents, several other reasons can be deduced why sleep problems go by undetected, and serve as important lessons for clinical practice. Firstly, parents indicated they were overloaded by care demands for their child. As a result, sleep may not be at the forefront of their minds and fail to receive priority on their extensive list of topics that need to be discussed with their doctor. Therefore, it is essential for parents that clinicians take the initiative and responsibility by regularly asking them about sleep. Secondly, parents indicated that caring for their child’s sleep is paramount and they feel that providing care at night is something that is expected from them as parents. As a consequence, they may not recognise their child’s sleep as problematic. This is supported by previous research showing discrepancies between parent-reported sleep problems using objective criteria versus their subjective perceptions, i.e. parents do not always perceive their child as having a sleep problem even when it is present [Citation33]. When clinicians ask parents about sleep, they should take the extra step to dig a little deeper, in order to get a true understanding of what their nights look like. Objective, measurable questions like “Does your child wake up more than three times per night?” or “Does is take longer than 30 min for your child to fall asleep?” would serve as a good starting point to identify sleep difficulties [Citation34]. Thirdly, parents expressed a need to be heard and understood in a supportive manner. Those who felt judged by their healthcare professionals described feelings of insecurity for not taking good care of their child at night, and may therefore be less inclined to raise concerns [Citation35]. Therefore, professionals should acknowledge the sensitivity that surrounds the care for sleep of these children, taking on a coaching attitude towards parents without being judgmental. Considering these perspectives in clinical practice may prove beneficial in meeting parents’ collectively expressed need for sleep to receive more awareness within paediatric healthcare.

Recently, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Sets for children and youth with CP were developed during a consensus meeting with experts [Citation36]. Among these Core Sets, sleep was reported as one of the 25 functions considered most relevant for describing the child across all age groups between 0–18 years. The identified Core Sets serve to guide professionals in identifying areas of functioning that need to be addressed in this population, and offers support for the parental need to incorporate sleep into standard clinical assessment. In doing so, care for sleep should consider all different aspects captured within the ICF model, that may influence sleep, including body functions (e.g. spasticity, pain, airway obstructions, reflux), participation (e.g. fatigue or daytime sleepiness during school), as well as environmental (e.g. bedroom, parents) and personal factors (e.g. behaviour, sleep hygiene practices). Applying this framework when a child with CP and their family visit during clinical follow-up may guide professionals to avoid overlooking important aspects relevant for child-family functioning, including sleep.

A team of (non)medical specialists of various disciplines is often involved in the child’s rehabilitation care, but parents emphasised not knowing who exactly is responsible for care for sleep. According to parents, sleep is intertwined in all aspects of their child’s functioning, and should therefore be approached holistically with the combination of knowledge and expertise of all disciplines. Although CP is best managed in a multidisciplinary setting [Citation37], currently there is no standardised approach to sleep management within paediatric rehabilitation. Given the fact that the rehabilitation physician serves as an important gatekeeper in these settings, we propose that they are encouraged to adopt it as their responsibility to detect and monitor sleep problems, necessary to initiate multidisciplinary interventions.

In addition to needs described within the healthcare setting, an important parent-identified need raised within their home environment was the availability of social support. The influence of social support provided by immediate family, friends, and neighbours has been reported to indirectly affect the psychological health of parents of children with CP [Citation21] and should therefore not be forgotten. The sleep problems were often described by parents to be invisible to others around them. Hence, it can be challenging for their social environment to truly understand a situation that they are unaware of, cannot imagine, or simply do not recognise to be so tough. In fact, sleep disturbances in mothers with CP have been described to be comparable to those experienced by mothers caring for new-borns [Citation13]. Although peer caregivers of healthy children may experience similar problems during childhood, their child will likely outgrow the sleep issues and should realise that parents of a child with CP may carry this burden for a lifetime. Parents should feel encouraged to openly discuss these issues with their social network, who in turn are expected to offer support and acknowledgement for being tired, irritable or forgetful during the day as a result of being sleep deprived or (psychologically) exhausted.

Our findings on how parental concerns and needs map across different environmental settings, could provide a framework for targeting home-based versus healthcare-based intervention strategies. Home-based approaches should take into consideration specific concerns, and focus on what can be done to meet parents’ needs, in order to engage families in (implementing) intervention processes. For example, even establishing a good sleep hygiene, which is considered a simple but effective first-line treatment for sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders [Citation38], can be challenging in a complex child and family situation. Actively involving and educating parents to ensure that healthy sleep practices are implemented and maintained at home is therefore crucial [Citation39]. More efforts should be made to adopt a family-centered approach in relation to the care for child sleep. Intervention strategies related to the clinical setting may in turn require educating healthcare professionals to improve their sleep knowledge, as well as adaptations on an organisational level in order for sleep to become a standard item for review during routine health assessments. Moreover, effective sleep assessment should be broad enough to screen for all kinds of sleep issues, yet focused enough to target specific individual parental concerns and needs [Citation40]. This approach should result in healthcare-based interventions that are tailored to the unique and diverse family situations.

Strengths and limitations

It should be noted that the term ‘sleep problems’ in this article is solely based on parent reports (i.e. whether they perceive their child’s sleep as problematic or not) rather than on clinically diagnosed sleep problems. Though one could argue whether perceiving or having a problem is similar, the aim of this paper was to expose perspectives on care for sleep from a parental viewpoint.

Although we did not specifically recruit parents of children who experienced sleep problems in their child, those parents who participated may have been more concerned with sleep issues. Yet, not all parents included in this study mentioned sleep problems, and some of them still described concerns and needs related to their child’s care for sleep.

Four parents were reflecting on a past period when their child was aged 1–8 years rather than being interviewed about their current experiences. A potential recall bias of these parents could have impacted the data. On the other hand, the contributions of parents of older children could have enriched the data by introducing different perspectives on the care for sleep of their child during the same age period, but viewed in retrospect.

Parents of non-ambulatory children with CP have been reported to express more needs than parents of ambulatory children [Citation41]. It may well be that parents of the most severely impaired children experienced a greater burden of care demands at night, with a greater impact on family functioning and wellbeing. Concerns about sleep have been found to vary across ages in children and young people with CP, but are present at every GMFCS level [Citation40]. Despite the use of a convenience sampling method, we managed to reach great variation in age and GMFCS levels between children. This qualitative study was not designed to investigate correlations, but rather to explore the issues that families of a child with CP face with regard to care for sleep, across all levels of motor disability.

Similar to previous literature conducted in this field [Citation13,Citation21,Citation42,Citation43], our parent sample was dominated by (highly-educated) mothers. Since the responsibilities for caring for a child with a disability are attributed differently, i.e. based on gender [Citation44], mothers likely experience sleep problems differently. Future research should elucidate perspectives of fathers, as well as those of siblings and the children with CP themselves.

Conclusions

This qualitative study allowed us to hear the voices of parents by addressing their perspectives on the care for sleep of their child with CP. Parents face numerous challenges caring for their child’s sleep which are hampered by perceived shortcomings in healthcare. In order to prevent poor health outcomes in families of children with CP, sleep needs to be acknowledged within the paediatric setting. Clinicians should routinely inquire about sleep during clinical follow-ups, in order to identify sleep problems early on. A proactive, non-judgmental, and family-centered approach is needed from healthcare professionals.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the parents who shared their experiences with us, and parent organisations CP Nederland and OuderInzicht for their collaboration. We thank Barbara Uelkes and Nicole IJff for transcribing the interviews, Ian & Hilde Hall for their support in translating quotations, and Floryt van Wesel, expert in qualitative research, for her assistance in structuring categories and construction of themes during the analysis.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Oskoui M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, et al. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(6):509–519.

- Simard-Tremblay E, Constantin E, Gruber R, et al. Sleep in children with cerebral palsy: a review. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(10):1303–1310.

- Newman CJ, O'Regan M, Hensey O. Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(7):564–568.

- Horwood L, Mok E, Li P, et al. Prevalence of sleep problems and sleep-related characteristics in preschool- and school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Sleep Med. 2018;50:1–6.

- Hemmingsson H, Stenhammar AM, Paulsson K. Sleep problems and the need for parental night-time attention in children with physical disabilities. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(1):89–95.

- Dutt R, Roduta-Roberts M, Brown C. Sleep and children with cerebral palsy: a review of current evidence and environmental non-pharmacological interventions. Children (Basel). 2015;2(1):78–88.

- Adiga D, Gupta A, Khanna M, et al. Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy and its correlation with sleep disturbance in primary caregivers and other associated factors. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17(4):473–476.

- Kotagal S, Gibbons VP, Stith JA. Sleep abnormalities in patients with severe cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36(4):304–311.

- Garcia J, Wical B, Wical W, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in children with cerebral palsy and epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(10):1057–1062.

- Lélis A, Cardoso M, Hall WA. Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy: an integrative review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;30:63–71.

- Romeo DM, Brogna C, Quintiliani M, et al. Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy: neurodevelopmental and behavioral correlates. Sleep Med. 2014;15(2):213–218.

- Horwood L, Li P, Mok E, et al. Behavioral difficulties, sleep problems, and nighttime pain in children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;95:103500.

- Wayte S, McCaughey E, Holley S, et al. Sleep problems in children with cerebral palsy and their relationship with maternal sleep and depression. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(6):618–623.

- Chaput J, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:266–282.

- Meijer AM, Habekothé HT, Van Den Wittenboer GL. Time in bed, quality of sleep and school functioning of children. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(2):145–153.

- Astill RG, Van der Heijden KB, Van IJzendoorn MH, et al. Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzed. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(6):1109–1138.

- Horwood L, Li P, Mok E, et al. Health-related quality of life in Canadian children with cerebral palsy: what role does sleep play? Sleep Med. 2019;54:213–222.

- Sandella DE, O’Brien LM, Shank LK, et al. Sleep and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Sleep Med. 2011;12(3):252–256.

- Jan M. Cerebral palsy: comprehensive review and update. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26(2):123–132.

- Mörelius E, Hemmingsson H. Parents of children with physical disabilities - perceived health in parents related to the child’s sleep problems and need for attention at night. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(3):412–418.

- Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, et al. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e626–e636.

- Barlow JH, Cullen‐Powell LA, Cheshire A. Psychological well‐being among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Early Child Dev Care. 2006;176(3–4):421–428.

- Wright M, Tancredi A, Yundt B, et al. Sleep issues in children with physical disabilities and their families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2006;26(3):55–72.

- Verschuren O, Gorter JW, Pritchard-Wiart L. Sleep: an underemphasized aspect of health and development in neurorehabilitation. Early Hum Dev. 2017;113:120–128.

- Boeije H. Analysis in qualitative research. London (UK): Sage publications; 2009.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Quine L. Sleep problems in primary school children: comparison between mainstream and special school children. Child Care Health Dev. 2001;27(3):201–221.

- Guillamón N, Nieto R, Pousada M, et al. Quality of life and mental health among parents of children with cerebral palsy: the influence of self-efficacy and coping strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(11–12):1579–1590.

- Okurowska –Zawada B, Kułak W, Wojtkowski J, et al. Quality of life of parents of children with cerebral palsy. Prog Heal Sci. 2011;1(1):116–123.

- Owens JA. The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):e51–e51.

- Gruber R, Constantin E, Frappier JY, et al. Training, knowledge, attitudes and practices of Canadian health care providers regarding sleep and sleep disorders in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22(6):322–327.

- Bruni O, Violani C, Luchetti A, et al. The sleep knowledge of pediatricians and child neuropsychiatrists. Sleep Hypn. 2004;6(3):130–138.

- Robinson AM, Richdale AL. Sleep problems in children with an intellectual disability: parental perceptions of sleep problems, and views of treatment effectiveness. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(2):139–150.

- Moore M. Behavioral sleep problems in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(1):77–83.

- Norman C, Moffatt S, Rankin J. Young parents’ views and experiences of interactions with health professionals. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016;42(3):179–186.

- Schiariti V, Selb M, Cieza A, et al. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy: a consensus meeting. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(2):149–158.

- Panteliadis CP. Cerebral palsy: A multidisciplinary approach. 3rd ed. Cham (Switzerland): Springer; 2018.

- Jan JE, Owens JA, Weiss MD, et al. Sleep hygiene for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1343–1350.

- Blackmer AB, Feinstein JA. Management of sleep disorders in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a review. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(1):84–98.

- McCabe SM, Blackmore AM, Abbiss CR, et al. Sleep concerns in children and young people with cerebral palsy in their home setting. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51(12):1188–1194.

- Palisano RJ, Almarsi N, Chiarello LA, et al. Family needs of parents of children and youth with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(1):85–92.

- Bourke-Taylor H, Pallant JF, Law M, et al. Relationships between sleep disruptions, health and care responsibilities among mothers of school-aged children with disabilities. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(9):775–782.

- Unsal-Delialioglu S, Kaya K, Ozel S, et al. Depression in mothers of children with cerebral palsy and related factors in Turkey: a controlled study. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009;32(3):199–204.

- Traustadottir R. Mothers who care. J Fam Issues. 1991;12(2):211–228.