Abstract

Purpose

Worldwide, disability systems are moving away from congregated living towards individualized models of housing. Individualized housing aims to provide choice regarding living arrangements and the option to live in houses in the community, just like people without disability. The purpose of this scoping review was to determine what is currently known about outcomes associated with individualized housing for adults with disability and complex needs.

Methods

Five databases were systematically searched to find studies that reported on outcomes associated with individualized housing for adults (aged 18–65 years) with disability and complex needs.

Results

Individualized housing was positively associated with human rights (i.e., self-determination, choice and autonomy) outcomes. Individualized housing also demonstrated favourable outcomes in regards to domestic tasks, social relationships, challenging behaviour and mood. However, outcomes regarding adaptive behaviour, self-care, scheduled activities and safety showed no difference, or less favourable results, when compared to group homes.

Conclusions

The literature indicates that individualized housing has favourable outcomes for people with disability, particularly for human rights. Quality formal and informal supports were identified as important for positive outcomes in individualized housing. Future research should use clear and consistent terminology and longitudinal research methods to investigate individualized housing outcomes for people with disability.

Individualized housing models can foster self-determination, choice and autonomy for adults with disability and complex needs.

Having alignment between paid and informal support is important for positive outcomes of individualized housing arrangements.

A more substantial evidence base regarding individualized housing outcomes, in particular long-term outcomes, and outcomes for people with an acquired disability, is required.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Residential environments are significant social determinants of health that play an important role in promoting quality of life [Citation1–3]. Despite this, people with complex and significant disabilities (e.g., intellectual disability, brain injury, spinal injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy) have limited choice when it comes to housing and living arrangements [Citation4–7]. Traditionally, government funded housing developed for people with disability has tended to be separate from the community and congregated with other people who have disability [Citation7]. However, recent innovations and policy developments in the disability sector are now moving away from traditional congregated living settings and towards more individualized housing options [Citation8,Citation9]. Reflecting the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) [Citation10] principles, individualized housing aims to provide adults with disability (i.e., aged 18–65 years) choice regarding living arrangements, and the option to live in houses in the community just like people without disability. Given the recent policy developments guiding housing to become individualized and the significant impact these reforms will have on the lives of people with disabilityFootnote1, it is critical to understand the outcomes associated with individualized housing.

Complex needs refer to functional impairment which has a substantial impact on the person’s independence in one or more activities in the domains of mobility, self-care, domestic life, or self-management [Citation12]. The term complex needs is commonly used in the literature and policy to capture the breadth (i.e., multiple needs that are interrelated or interconnected) and depth of needs (i.e., profound, severe, serious or intense needs) of people with various disabilities [Citation13]. People with complex needs may have to negotiate a number of different issues in their life and often lack access to suitable housing or meaningful daily activity [Citation14].

Currently, a continuum of housing arrangements is available for people with disability and complex needs [Citation6]. This continuum broadly consists of four main streams: institutions (large residential centres, now predominantly closed), group homes (smaller residential centres with shared facilities and often shared support), living with parents beyond the age when people would usually leave (often living with ageing carers) and living in the community with support (i.e., individualized housing) [Citation6]. Since the closure of institutions, group homes have become a dominant form of housing and support for adults with disability [Citation15,Citation16]. Although group homes aim to resemble suburban homes, in this model people with disability are often treated as service users or recipients of care who live according to staff routines, rosters and priorities [Citation17]. Thus, similar to institutional care environments, group homes maintain large power imbalances between staff and residents, and service centred terminology is typically used to describe them [Citation17]. Concerns about group homes have been raised due to the limited choice available to residents regarding with whom and where they live, as well as inadequate engagement and participation outcomes [Citation18–20]. Research findings also suggest people living in group homes are vulnerable to abuse and neglect [Citation21–25]. In recognition of the potential negative outcomes, international trends in living arrangements for people with disabilities are now moving away from group homes and towards more individualized housing options which aim to prioritise principles of self-determination and community inclusion [10; Article 19].

Individualized housing refers to housing options that are life stage appropriate, where people with disability have choice regarding where and with whom they live, the support they receive and their day to day activities [Citation6]. An important goal of individualized housing is to support people’s choice and control over decisions that affect their lives [Citation26]. Such choices include smaller decisions about everyday living (e.g., sleep and wake times, meal content etc) through to more complex choices (e.g., type of support, who provides support, which community-based facilities to use or how to participate in the community) [Citation27]. Therefore, as these living arrangements are modified depending on personal preferences and type of disability the way they are implemented can vary substantially from person to person [Citation26]. Research has highlighted self-determination and autonomy as important contributing factors to quality of life, indicating that more individualized housing arrangements are likely to have beneficial outcomes [Citation28]. Previous research comparing quality of life outcomes between group homes and individualized housing options has found mixed results [Citation29,Citation30]. While more individualized housing arrangements have been shown to have better outcomes on domains of choice, frequency, and range of recreational or community-based activities, group homes have yielded better outcomes in terms of safety, frequency of scheduled activities, health, and money management [Citation29,Citation30]. The outcomes associated with individualized housing options therefore remain unclear.

Although it is recognised that the specific needs of adults with acquired neurological disability differ from adults with developmental intellectual disability, people with both forms of disability experience functional impairments which create challenges in one or more of the mentioned domains [Citation17]. Accordingly, people with acquired neurological disability and developmental intellectual disability have experienced similar housing options [Citation17]. That is, institutions, group homes, living with biological families and more recently individualized housing [Citation6]. It is therefore essential to understand the outcomes of individualized housing for people with both forms of disability.

As countries around the world have signed and ratified the UNCRPD, there is currently a strong international focus on the provision of suitable, affordable housing for people with disability and on maintaining people’s right to choose where they live [Citation10].

Many governments have introduced individualized funding programs for people with disability [Citation31]. In some jurisdictions specific funds dedicated to specialist disability housing are available [Citation32]. For example, policy developments in Australia now allow some people with severe disability to access individualized funding for housing and therefore the potential to exercise choice between available housing options [Citation33]. One purpose of individualized funding is to support people to move away from group homes or congregate settings into their own home, if that is their preference [Citation20]. Accordingly, the number of people with disability who choose to live in individualized housing options is anticipated to increase [Citation7]. Given these policy developments towards more individualized housing models, it is critical to understand the outcomes associated with individualized housing. Therefore, the primary aim of this scoping review was to determine what is known about outcomes of individualized housing for adults with disability and complex needs.

Methods

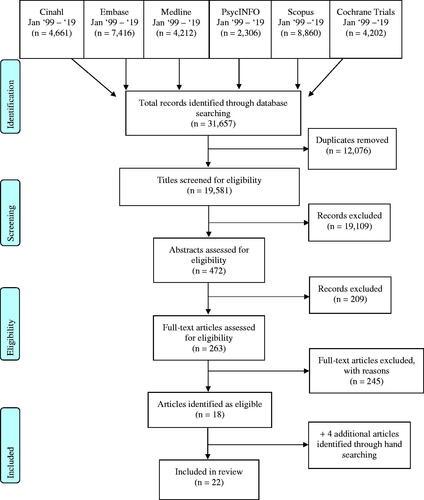

A scoping review method was considered most appropriate for the current study as this method is effective in answering broad questions where there is emerging evidence about a topic [Citation34,Citation35]. Reporting of the method and results was guided by The Prisma Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation [Citation36]. The research question guiding the review was “What are the outcomes associated with individualized housing options for adults with disability and complex needs?” Three concepts informed the development of the key words that were used in the final search. The first concept described the population (i.e., persons with physical, sensory, or cognitive disability including intellectual/developmental, and neurological disorders with complex needs) the second concept reflected the setting of interest (i.e., individualized housing options or home-like settings) and the third concept reflected outcomes associated with living arrangements (i.e., quality of life, self-determination, community participation, cost). A search strategy based on these concepts was developed and adapted for each database with consultation from a research librarian (see online supplementary file for detailed search strategy). Literature searches were carried out in January 2019 for studies published over the past 20 years (since 1999). This period was chosen as most developed countries had undergone significant disability policy reforms resulting in the closure of institutions, and an emphasis on community-based living [Citation37–39]. Databases searched were Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Scopus and Embase (MeSH terms were added in MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Embase).

Following the initial inclusion criteria outlined in , a selection of 200 titles were blind screened by two reviewers (EGK and SO) which demonstrated 92% interrater agreement. At each stage of the review, conflicts were resolved through discussion. The remaining titles were independently screened by the two primary reviewers (EGK and SO). After title screening, the remaining abstracts were double blind reviewed by two reviewers (EGK and SO). Following abstract screening, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were tightened for full text screening (see ). The exclusion criteria for study design required significant adjustment. In line with the primary aim of the review, seven additional study design criteria were developed to ensure that findings related to individualized housing outcomes for the relevant population. Specifically, if results of individualised housing outcomes for adults (18–65 years) who had complex needs living in individualized housing, were unable to be isolated, the article was excluded.

Table 1. Exclusion criteria development.

It was identified at this stage of the review that consistency of terminology was an issue across articles. Therefore, guiding terms which indicated housing status were used to determine whether an article was referring to an individualized home, or to a housing arrangement that was not relevant to the current review (i.e., group homes or institutions). The guiding terms reflected both descriptors (e.g., purpose-built apartment) and characteristics (e.g., tenancy rights, choice regarding where and who to live with) of housing arrangements. Additionally, some terms used in the literature were recognised as being ambiguous. Often these terms had various meanings across countries, the meaning of the term had changed over time, or the terms were used differently depending on personal interpretations. When these terms were used in the literature, additional information that indicated the article was referring to individualized housing was also required in order to be included in the review. provides a summary of the guiding terms used to indicate housing type. Articles in which the population or housing arrangements were not described were excluded. All full text articles were double blind reviewed by two reviewers (EGK and SO). Any disagreements and uncertainties regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles were discussed by the primary screening reviewers (EGK, and SO), with the input of two independent review authors (DW and JD). Articles that were identified as meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria after full text screening were assessed by the review team (DW, EGK, JD and SO) for final agreement for inclusion.

Table 2. Guiding terms used to indicate housing type.

In total, the literature search retrieved 31,657 articles. After removing duplicates, 19,581 titles were screened by two independent reviewers. Based on the eligibility criteria outlined 19,109 articles were excluded at title screening. Abstracts of the remaining articles were examined to determine eligibility, resulting in the exclusion of a further 209 articles and 263 articles remaining. Using the revised exclusion criteria, an additional 245 articles were excluded based on an in-depth assessment of the full text. Upon full text screening, articles were excluded for the following reasons: 58 due to population; 66 due to setting, 70 due to study design; 41 due to publication type and 10 articles could not be accessed (refer to for detailed exclusion reasons). Four additional articles were identified through forwards and backwards citation searches of the 263 articles that were included for full text screening. Data was extracted from the final 22 Articles [Citation40–61]. The reporting of study selection was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [Citation62] (see ).

Data extraction

For the 22 papers included in the review, the following data were extracted and recorded into various tables: authors, date of publication, country of research, details of participants (including type of disability, comorbidities and number of participants in different settings), study design, measures utilised, outcomes assessed in the research, and significant outcomes associated with individualized housing. Comparative data analyses were only extracted if comparisons were between individualized housing models and other forms of housing (i.e., group homes or congregated care settings). As previously discussed, the reviewed literature utilised a variety of terminology regarding individualized housing models. In order to stay true to the original meaning, data were extracted and reported using the primary sources language.

Results

Participant characteristics

The 22 identified studies shared a number of common characteristics. As can be seen in , of the studies included, 18 primarily recruited participants with intellectual disability, learning disability or “mental retardation”Footnote2. One study focused on people primarily with spinal cord injury and two studies recruited participants with acquired brain injury. Participants comorbidities were reported in 9 studies. As per the exclusion criteria, all studies reported on participants between 18–65 years, with most reporting on a population with a mean age of approximately 40 years. Most studies reported on samples that consisted of over 50% males [Citation40,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45–48,Citation53,Citation57,Citation59–61] and two studies reported on a sample that was 100% male [Citation49,Citation50]. The number of participants included in the studies ranged from 6 to 8,892 people. The studies included in the review reported on a variety of respondents’ perspectives (see for summary). In accordance with the exclusion criteria, all studies reported on participants with moderate-severe disability.

Table 3. Participant characteristics.

Health condition or diagnosis

Findings regarding participants health condition(s) in more individualized housing options were mixed. Multiple studies found no difference in the presence of psychiatric disorders or the presence of autism spectrum disorder across living conditions (i.e., supported living, personalized arrangements, own home, group homes and institutions) [Citation42,Citation51,Citation58]. Conversely, Felce et al. [Citation44] found people living independently were less likely to have the triad of impairments indicative of autism than people living in family or group homes. Additionally, Ticha et al. [Citation58] found people with disability living in their own home were less likely to have a profound intellectual disability, mobility limitations, a vision impairment or a hearing impairment, compared to people living in large institutional settings (16 + residents). McConkey et al. [Citation51] reported that people with a history of epilepsy were less commonly provided the opportunity to live in personalized arrangements, and tended to be placed in group homes. One study reported that a significantly higher proportion of people with spinal cord injury lived in their own home, rather than in nursing homes or homeless shelters [Citation47]. Results from three studies that sought matched samples suggest that people with disability and complex needs can live in individualized settings (i.e., supported living, semi-independent living or community residences) when provided the opportunity [Citation40,Citation57,Citation60].

Study characteristics

An overview of the characteristics, outcomes assessed and main findings of the studies included in the review is provided in . Of the studies included, 3 used a qualitative methodology, 18 were quantitative and 1 utilised a mixed methods design. The studies originated from a variety of countries, with 7 from the USA, 3 from Australia, 3 from the United Kingdom, 3 from Ireland, 2 from Canada, 1 from Finland, 1 from Wales, 1 from Columbia and 1 from The Netherlands.

Table 4. Study characteristics and outcomes.

Findings

The primary aim of this review was to identify the outcomes of individualized housing for adults with disability. To identify the quantitatively assessed outcomes, the measures utilized in the quantitative and mixed methods studies were mapped onto the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation12]. As can be seen in , the most commonly used outcome measures focused on the person’s activities and participation (e.g., relationships and resident choice) and environmental context (e.g., support and safety). Quantitative and qualitative findings are reported using the domains of ICF framework in the following section.

Table 5. Quantitatively assessed outcomes mapped onto the international classification of functioning, disability and health.

Body function

Quantitative findings

According to the ICF, mental functions are a subcomponent of body functions. The quantitative research included in the current review investigated global mental functions, such as challenging behaviour (any behaviour that causes significant distress or danger to themselves or others), and specific mental functions such as emotional functioning (any mental functions related to the feeling and affective components of the mind) [Citation12]. Marlow and Walker [Citation39] found participants challenging behaviour decreased following a move from group homes into individual flats and that these changes were maintained after six months. Additionally, Felce et al. [Citation44] found that people living independently were less likely to have challenging behaviour than people living in family or group homes. Emerson et al. [Citation42] found no difference in challenging behaviour across living conditions, which included group homes, institutions and the participants own home. However, results of Emerson et al. [Citation42] may be influenced by a cohort effect as participants included people who had experienced institutional living. In regards to emotional functioning, Marlow and Walker [Citation49] found that people’s mood increased one month after they moved from group homes into individualized flats and that these changes were maintained after six months. Valk-Kleibeuker et al. [Citation59] found that mood did not change for participants in their study until 18 months post traumatic brain injury (TBI), after which it significantly improved. Similarly, discharge destination after TBI was a significant predictor of mood. Patients who were directly discharged home had better mood scores over a three-year period compared to patients who were treated in an inpatient rehabilitation centre or nursing home [Citation59]. Taken together, these findings indicate that individualized housing options have favourable outcomes for challenging behaviour and mood.

Qualitative findings

Within the domain of body function, the qualitative research focussed predominantly on emotional function. Personalised residential settings were reported to enhance general wellbeing due to an enhanced lifestyle that offered growth and development [Citation41]. The importance of emotional and behavioural self-control was also highlighted in the qualitative literature as factors that contributed to the success of independent living in the community [Citation41,Citation50].

Activities and participation

Quantitative findings

Quantitative findings regarding activities and participation, including adaptive behaviour, varied between living conditions. Adaptive behaviour is the collection of conceptual, social, and practical skills learned by people to enable them to function in their everyday lives [Citation12]. Outcomes regarding adaptive behaviour, as well as general tasks and demands, commonly showed no differences between individualized housing options (i.e., supported living, independent living and independent flats) and group homes [Citation40,Citation44,Citation49,Citation56,Citation58]. Similarly, findings for self-care showed no difference for people in supported living or independent flats and group homes [Citation42,Citation49]. However, residents living semi-independently or independently, participated in significantly more domestic tasks, such as household cleaning, cooking, shopping and related tasks, compared to people living in family and staffed homes [Citation44,Citation57].

Mixed results were also evident for interpersonal interactions and relationship outcomes. A handful of studies found that living in group homes was associated with more scheduled social and community activity [Citation42,Citation44] and more frequent community connections [Citation56] when compared to independent living, supported living or living in an independent home or apartment. One study found that people in supported living arrangements (including living alone, in a home-share or with formal support arrangements) had low levels of friendship activities, and that residential setting was an important determinant of the form and content of activities with friends [Citation43]. In contrast, it was commonly reported that people living in personalized arrangements experienced more social relationships and interactions with friends, including inviting friends or relatives over for meals and giving and receiving help from neighbours compared to residents in group homes [Citation51–55]. Further, supported living residents had more access to social clubs [Citation40], personalized living residents engaged in more fitness activities (e.g., sports or group fitness classes) and were more likely to be attending education or training courses [Citation53], and semi-independent residents more frequently visited community places without paid support compared to group home residents [Citation57]. One study investigated social relationships in different living arrangements and found that people who had moved to personalized living settings reported a significant increase in social relationships and more social relationships overall than group home residents, and these differences were maintained over 24 months [Citation51]. Two recent studies found that people who lived in their own homes, experienced significantly greater community integration and inclusion compared to group homes or institutional settings [Citation45,Citation55].

Outcomes regarding major life areas and human rights unanimously favoured more individualized housing options [Citation42,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation52,Citation54,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60,Citation61]. Specific areas investigated included job satisfaction [Citation60], personal outcomes (e.g., affiliation, identity, goal attainment) [Citation46], quality of life [Citation49,Citation57] and well-being [Citation52]. Studies that investigated levels of choice, autonomy and self-determination all favoured individualized housing options (i.e., supported living, community living, own home), compared to group-home settings [Citation42,Citation45,Citation48,Citation54,Citation55,Citation58,Citation60,Citation61].

Qualitative findings

Similar activity and participation outcomes identified in the quantitative studies were also found in qualitative literature. Cocks et al. [Citation41] reported that people in supported living arrangements participated in a range of household activities including domestic duties, as well as social and community activities. Common barriers to achieving positive outcomes when living in private residences identified in the qualitative literature were social inclusion or the availability of meaningful occupation options [Citation47,Citation50] and financial management or money problems [Citation47,Citation50]. Outcomes regarding major life areas and human rights identified in the reviewed qualitative literature were similar to outcomes found in the quantitative literature. Specifically, increased autonomy and privacy were identified as common outcomes of living in supported living, private residences and apartments [Citation41,Citation47,Citation50].

Environmental factors

Quantitative findings

In regards to the physical environment, Emerson et al. [Citation42] found that significantly more supported living residents reported home-like settings (e.g., architectural features) when compared to large group home residents. Findings regarding support and relationships were mixed. One study found no difference in support when comparing supported living residents’ experiences and group home residents’ experiences [Citation40], whereas Stainton et al. [Citation56] found that residents in group homes reported significantly greater access to, delivery of, and assistance arranging, support compared to residents in independent living arrangements. In contrast, Emerson et al. [Citation42] reported that a significantly higher proportion of supported living residents reported desirable support characteristics, such as support and housing being provided by different agencies. Additionally, Sheth et al. [Citation55] found that people who lived in their own homes had significantly better experiences with personal care and were more likely to have access to the bathroom and medication when needed compared to people who lived in institutional settings. Outcomes relating to services, systems and policies were also inconsistent between studies. Although supported living residents reported higher staffing ratios as well as better internal procedures for allocating staff support based on individual needs, they were significantly less likely to have a key worker or an Individual Habilitation Plan (i.e., support plan), and staff were less likely supported in regards to assessment and teaching compared to group homes [Citation42]. Additionally, one study found no differences in safety between living conditions [Citation57], whereas Emerson et al. [Citation42] reported that supported living residents were more likely to have their home vandalized and were considered at greater risk of exploitation. Of the studies that investigated differences in cost outcomes, one found no difference in service costs [Citation42] and two found that semi-independent and supported living housing options had significantly lower support costs than group homes [Citation42,Citation57].

Qualitative findings

The qualitative literature also recognised the diversity of living arrangements that can be successful for people with disability [Citation41,Citation50]. Formal and informal support environments were identified as being critical for the success of living in individual apartments and supported living arrangements [Citation41,Citation50], as well as living in environments that are suitable for individuals’ physical, support or health needs [Citation41,Citation47,Citation50].

Body structures

Quantitative findings

Findings regarding body structures in the reviewed quantitative literature indicate that individualized housing is suitable for people with high support needs. McConkey et al. [Citation42] found that people living in personalised arrangements had improved well-being scores after moving from group homes, and that these changes were significantly higher for persons with higher support needs. Similarly, McConkey et al. [Citation51] found that on average although residents in group homes had the highest support needs, people with high support needs were also accommodated in personalised settings. One study found that for residents in supported living, significant or chronic health conditions were associated with poorer quality of life outcomes, indicating that greater health support is required for this cohort [Citation40].

Qualitative findings

Findings in the qualitative literature regarding body structures were similar to those reported in the quantitative literature. Specifically, Cocks et al. [Citation41] reported that all people with a disability, no matter how high and/or complex their needs, can live in a personalised residential setting if it is sufficiently flexible and resourced.

Discussion

This scoping review has documented the outcomes associated with individualized housing for people with disability and complex needs as reported in the peer-reviewed literature. Individualized housing arrangements consistently demonstrated favourable human rights outcomes, specifically for self-determination, choice and autonomy [Citation42,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation52,Citation54,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60,Citation61]. Individualized housing options also demonstrated favourable outcomes in regards to social relationships [Citation51–53], challenging behaviour [Citation42,Citation44,Citation49], mood [Citation49,Citation59] and participation in domestic tasks [Citation44,Citation57]. These findings align with previous research that has highlighted the benefits of individualized housing regarding self-determination, functional skills improvement, meaningful social interaction and psychological wellbeing [Citation29,Citation63–67]. In contrast, outcomes regarding adaptive behaviour, self-care, scheduled activities and safety showed no difference, or less favourable results, when compared to group homes [Citation40,Citation42,Citation44,Citation46,Citation56,Citation57]. The reviewed literature also demonstrated the importance of formal and informal supports for the success of individualized living arrangements [Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation50,Citation56]. There were many significant gaps in the research, including an absence of systematic and comprehensive evidence of the outcomes associated with individualized housing, particularly for people with acquired disability and complex needs.

The reviewed literature identified some important factors that contributed to the outcomes of individualized housing arrangements. It was commonly found that having a mix of paid support and informal support through relationships and friendships was beneficial for people living in individualised housing arrangements [Citation41,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation56]. Importantly, a good working relationship (e.g., frequent communication and involvement from both parties) between formal and informal supports was highlighted as contributing to the success of individualised housing [Citation41,Citation50]. This finding is consistent with previous research that has highlighted the importance of support [Citation26,Citation68,Citation69], and reflects the UNCRPD emphasis on the provision of appropriate support. Notable barriers to positive outcomes in individualized housing included having limited finances [Citation48,Citation50], money management [Citation41], vulnerability to substance abuse [Citation41] and being unable to access transportation [Citation47,Citation55]. The primary aim of the current review was to identify outcomes associated with individualised housing and in doing so, some important barriers and facilitators for the success of these arrangements have been identified. Further investigation regarding what specific features of individualized housing arrangements benefit or hinder the outcomes of people with disability is required.

Two studies found that outcomes of people living in individualized housing changed over time. Marlow and Walker [Citation49] found that tenants’ mood improved following the move from group homes into individualized flats and that these changes were maintained after six months. Additionally, Valk-Klebeuker et al. [Citation59] investigated the course of mood and its determinants over a three-year period following TBI. It was found that patients who were directly discharged home had better mood scores over time compared to patients who were treated in an inpatient rehabilitation centre or nursing home. Interestingly, mood did not change until 18 months post TBI, after which it significantly improved. One study found that people who moved to personalized arrangements had more social relationships compared to people who remained in group settings and that these changes were maintained after 24 months [Citation53]. These findings indicate that living in individualized housing is likely to have ongoing and changing effects on health and wellbeing, particularly when people are adjusting to their new way of life. However, of the studies included in the review, just three studies reported follow-up outcomes. Thus, future research should endeavor to further investigate how the experiences, outcomes and needs of this population change over time by conducting longitudinal follow-up studies. This information would be valuable for the development of effective and sensitive policy initiatives that aim to support and transition people to more individualized housing options.

A number of important research gaps have been identified through this scoping review. The lack of detailed descriptions regarding housing arrangements created a significant challenge in identifying relevant studies, summarizing the research findings, and drawing conclusions regarding the outcomes associated with housing models. Previous literature reviews on specialist housing models have found similar results regarding housing descriptions [Citation66,Citation70–73]. Terms used within the field to describe housing (e.g., independent living, assisted living, supported housing) do not have a commonly understood meaning. Although authors or experts in one jurisdiction may know what is meant by a given term, the same meaning may not be shared by others [Citation72]. Providing clear and detailed descriptions of housing arrangements is crucial in ensuring accuracy in the interpretation and application of research findings to inform policy and practice [Citation66,Citation70–73]. It is important for future research to clearly describe housing arrangements by explicitly stating the specific living arrangements they are referring to (see Friedman [Citation45] for example).

Another major gap concerns the absence of comprehensive evidence on the outcomes for people with acquired disability and complex needs in regards to individualized housing. The majority of studies included in the review investigated outcomes specifically for people with intellectual disability. Although this research can provide valuable insights regarding housing outcomes, the nature and degree of functional limitations experienced by people with other forms of disability such as an acquired neurological disorder (e.g., brain injury, spinal cord injury, progressive neurological disorders) are different to those encountered by people with intellectual disability [Citation74]. Unfortunately, the severity of physical limitations was only reported in a handful of studies [Citation40,Citation46,Citation48,Citation49,Citation58], so substantial conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the appropriateness of individualized housing for people with significant physical limitations. Previous research has documented the different employment outcomes [Citation75] and support needs [Citation67] for people with physical impairments or acquired neurological disabilities compared to people with intellectual disability. It is therefore likely that living in individualized housing will be associated with unique outcomes for people with different types of disabilities. It is important for future research to investigate outcomes of individualized housing for people with various types of disability (e.g., acquired and progressive neurological disorders) to develop a more comprehensive understanding of what makes individualized housing options successful, as well as what barriers exist, for different cohorts.

Lastly, between studies included in the review, a range of assessment tools and study designs were used to assess a variety of participant outcomes. The diversity of measures utilized between studies posed a challenge when comparing and contrasting research findings, and likely contributed to some of the mixed findings found in the current review. Additionally, multiple studies relied on administrative data [Citation57], convenience data [Citation43–45], population data [Citation42,Citation46,Citation48,Citation58] or unvalidated measures [Citation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation57]. Future research should aim to use standardized outcome measures so that findings can be more easily validated, accumulated and compared. In terms of study design, most studies included in the current review utilised observational or nonrandomized experimental designs. Therefore, none of the studies could conclude that the housing model caused changes in participant outcomes. So that we can consider directionality, and outcomes of housing models can be adequately compared, future research should endeavour to recruit random samples and when possible utilise quasi-experimental interventions, pretest-posttest designs, randomised controlled trial or single case experimental study designs.

Findings from the current review suggest that support arrangements are not adequate in some individualized housing options, and as a result may be impairing the outcomes of people with disability [Citation40,Citation41,Citation47,Citation50]. Previous research investigating similar housing models has also highlighted the importance of well-structured support models that consist of paid support as well as family, friends and community members [Citation26,Citation67,Citation76]. In Australia, the Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) program was developed to encourage investment and growth in individualized housing options for people with disability [Citation77]. With the introduction of the SDA, it is anticipated that a substantial increase of people with disability will chose to live in individualized housing options [Citation77]. It is therefore crucial that policy is refined to be sensitive to both formal and informal support arrangements for people with disability.

A rigorous scoping review methodology using established methods was conducted to map the existing literature of the outcomes associated with individualized housing for adults with disability and complex needs. Although scoping reviews are not designed to give weight to studies’ findings based on quality assessment, it is valuable to note the diversity in the quality of studies included in the review, which must be considered when interpreting the findings in the current review. Additionally, in order to comprehensively capture outcomes of individualized living, literature spanning over the past 20 years was included in the review. Therefore, it should be considered that some of the included articles utilise data from a cohort that experienced traditional institutional living arrangements. It is also noteworthy that studies that investigated body structures tended to include older adults (>40 years) as participants [Citation40–42,Citation51]. Therefore, findings indicating that poorer body function outcomes are associated with congregate care may be confounded with issues related to aging. The possibility that all relevant articles may not have been captured through the search strategy is a risk of any systematic or scoping review. Although our search was quite comprehensive, there is still the possibility that we may not have captured all available studies.

Overall, this review has highlighted the potential of individualized housing options to offer improved self-determination, choice and autonomy for people with disability and complex needs. A good working relationship between formal and informal supports was identified as being important for the success of individualised housing arrangements. It is important for future research to clearly describe the housing arrangements they are investigating and use rigorous research methods to effectively inform practice and policy. There is still a considerable need to build a more substantial evidence base regarding individualized housing outcomes, in particular for people with an acquired disability, as well as the long-term outcomes of individualized housing. Policy developments should focus on ensuring effective formal and informal support arrangements are in place for people with disability who choose to live in individualized housing options.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The current article will use person-first language consistent with the UNCRPD, and as recommended by International Language Guidelines on Disability [Citation11].

2 To ensure accuracy in reporting, this scoping review uses the original terminology of the articles we have reviewed. However, it is important to note that while "mental retardation" was a historically accepted term, the presently accepted nomenclature is "intellectual disability" or “learning disability”.

References

- Veitch JA. Investigating and influencing how buildings affect health: interdisciplinary endeavours. Can Psychol. 2008;49(4):281–288.

- Kyle T, Dunn JR. Effects of housing circumstances on health, quality of life and healthcare use for people with severe mental illness: a review. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16(1):1–15.

- Kavanagh AM, Aitken Z, Baker E, et al. Housing tenure and affordability and mental health following disability acquisition in adulthood. Soc Sci Med. 2016;151:225–232.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Current and future demand for specialist disability services. Canberra: AIHW; 2007.

- Bridge C, Flatau P, Whelan S, et al. Housing assistance and non- shelter outcomes. AHURI. 2003;40:1–84.

- Connellan J. Commentary on Housing for People with Intellectual Disabilities and the National Disability Insurance Scheme Reforms (Wiesel, 2015). Res Pract Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;2(1):56–59.

- Wiesel I. Housing for people with intellectual disabilities and the National Disability Insurance Scheme reforms. Res Pract Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;2(1):45–55.

- HM Government. Hate crime – the cross-government action plan. London: Home Office; 2009.

- Department of Health. Transforming care: a National response to Winterbourne View Hospital. London: Department of Health and Social Care; 2012. (Report No. 18348).

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106; 2007 [cited 2020 May]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.htm

- International Foundation for Electoral Systems. International language guidelines on disability. Arlington (VA): International Foundation for Electoral Systems; 2017.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Rosengard A, Laing I, Ridley J, et al. A literature review on multiple and complex needs. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2007.

- Rankin J, Regan S. Meeting complex needs in social care. Hous Care Support. 2004;7(3):4–8.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability support services: services provided under the National Disability Agreement 2012–13. Canberra: AIHW; 2013.

- Beadle-Brown J, Mansell J, Kozma A. Deinstitutionalization in intellectual disabilities. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(5):437–442.

- Keogh F. Disability and mental health in Ireland: searching out good practice Ireland. Mullingar, Ireland: Genio; 2009.

- Mansell J, Beadle-Brown J, Bigby C. Implementation of active support in Victoria, Australia: an exploratory study. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;38(1):48–58.

- Productivity Commission. Disability Care and Support, Productivity Commission Inquiry: Report. Canberra: Australian Government; 2009. (Report no. 54).

- Wiesel I. Allocating homes for people with intellectual disability: needs, mix and choice. Soc Policy Admin. 2011;45(3):280–298.

- Balandin SU. Witnessing without words. Intellectual disability & the law: contemporary Australian issues. Aus Soc Stud Intellect Disabil. 2000;1:31–40.

- Carr S. Enabling risk, ensuring safety: Self-directed support and personal budgets. London (UK): SCIE; 2013. (Report no. 36)

- Disability Services Commissioner Victoria. Learning from Complaints Occasional Paper No. 2, Developing policy principles and strategies to support families of adults with a disability and disability service providers to work more effectively together. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria; 2014.

- Marsland D, Oakes P, Bright N. It can still happen here: systemic risk factors that may contribute to the continued abuse of people with intellectual disabilities. Tizard Learning Disability Rev. 2015;20(3):134–146.

- Marsland D, Oakes P, White C. Early Indicators of Concern in Residential Support Services for People with Learning Disabilities. The Abuse in Care? Project. Hull (UK): Centre for Applied Research and Evaluation: October; 2012.

- Taleporos G, Craig D, Brown M. Housing and support for younger people with disabilities transitioning to independent living: Elements for success in the design and implementation of disability care Australia, a National Disability Insurance Scheme. Melbourne (VIC): Youth Disability Advocacy Service; 2013.

- Douglas J, Bigby C. Development of an evidence-based practice framework to guide decision making support for people with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury or intellectual disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):434–441.

- Miller SM, Chan F. Predictors of life satisfaction in individuals with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52(12):1039–1047.

- Howe J, Horner RH, Newton JS. Comparison of supported living and traditional residential services in the state of Oregon. Ment Retard. 1998;36(1):1–11.

- Stancliffe RJ. Community living-unit size, staff presence, and residents' choice-making. Ment Retard. 1997;35(1):1–9.

- Lord J, Hutchison P. Individualised support and funding: building blocks for capacity building and inclusion. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(1):71–86.

- Tøssebro J. Scandinavian disability policy: From deinstitutionalisation to non-discrimination and beyond. Alter. 2016;10(2):111–123.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. Canberra: Parliament of Australian; 2013. (No. 20).

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Davis DL, Fox-Grage W, Gehshan S. Deinstitutionalization of persons with developmental disabilities: a technical assistance report for legislators. Denver: National Conference of State Legislatures; 2004.

- Bostock L, Gleeson B, McPherson A, et al. Deinstitutionalisation and housing futures: Positioning paper. Melbourne: University of New South Wales and University of Western Sydney Research Centre, Australian Housing and Research Institute; 2000.

- Emerson E. Deinstitutionalisation in England. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2004;29(1):79–84.

- Bigby C, Bould E, Beadle-Brown J. Comparing costs and outcomes of supported living with group homes in Australia. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2018;43(3):295–307.

- Cocks E, Thoresen SH, O'Brien P, et al. Examples of individual supported living for adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2016;20(2):100–108.

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Gregory N, et al. Quality and costs of supported living residences and group homes in the United Kingdom. Am J Mental Retard. 2001;106(5):401–415.

- Emerson E, McVilly K. Friendship activities of adults with intellectual disabilities in supported accommodation in Northern England. J Appl Res Int Dis. 2004;17(3):191–197.

- Felce D, Perry J, Kerr M. A comparison of activity levels among adults with intellectual disabilities living in family homes and out‐of‐family placements. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2011;24(5):421–426.

- Friedman C. The influence of residence type on personal outcomes. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2019;57(2):112–126.

- Gardner JF, Carran DT. Attainment of personal outcomes by people with developmental disabilities. Ment Retard. 2005;43(3):157–174.

- Ho PS, Kroll T, Kehn M, et al. Health and housing among low- income adults with physical disabilities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4):902–915.

- Houseworth J, Stancliffe RJ, Tichá R. Association of state-level and individual-level factors with choice making of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;83:77–90.

- Marlow E, Walker N. Does supported living work for people with severe intellectual disabilities? Adv Mental Hlth Intell Disabil. 2015;9(6):338–351.

- McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, et al. Transitions to independent living after ABI. Brain Inj. 1999;13(5):311–330.

- McConkey R, Keogh F, Bunting B, et al. Relocating people with intellectual disability to new accommodation and support settings: Contrasts between personalized arrangements and group home placements. J Intellect Disabil. 2016;20(2):109–120.

- McConkey R, Keogh F, Bunting B, et al. Changes in the self-rated well-being of people who move from congregated settings to personalized arrangements and group home placements. J Intellect Disabil. 2018;22(1):49–60.

- McConkey R, Bunting B, Keogh F, et al. The impact on social relationships of moving from congregated settings to personalized accommodation. J Intellect Disabil. 2019;23(2):149–159.

- Saloviita T, Åberg M. Self-determination in hospital, community group homes, and apartments. Br J Dev Disabil. 2000;46(90):23–29.

- Sheth AJ, McDonald KE, Fogg J, et al Satisfaction, safety, and supports: Comparing people with disabilities' insider experiences about participation in institutional and community living. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(4):712–717.

- Stainton T, Brown J, Crawford C, et al. Comparison of community residential supports on measures of information & planning; access to & delivery of supports; choice & control; community connections; satisfaction; and, overall perception of outcomes. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55(8):732–745.

- Stancliffe RJ, Keane S. Outcomes and costs of community living: a matched comparison of group homes and semi-independent living. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2000;25(4):281–305.

- Tichá R, Lakin KC, Larson SA, et al. Correlates of everyday choice and support-related choice for 8,892 randomly sampled adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in 19 states. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50(6):486–504.

- Valk-Kleibeuker L, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Ribbers GM. Mood after moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2014;9(2):e87414.

- Wehmeyer ML, Bolding N. Self-determination across living and working environments: a matched-samples study of adults with mental retardation. Ment Retard. 1999;37(5):353–363.

- Wehmeyer ML, Bolding N. Enhanced self-determination of adults with intellectual disability as an outcome of moving to community-based work or living environments. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2001;45(Pt 5):371–383.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269.

- Kozma A, Mansell J, Beadle-Brown J. Outcomes in different residential settings for people with intellectual disability: a systematic review. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;114(3):193–222.

- Lakin KC, Stancliffe RJ. Residential supports for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):151–159.

- Felce D, Perry J, Romeo R, et al. Outcomes and costs of community living: semi-independent living and fully staffed group homes. Am J Ment Retard. 2008;113(2):87–101.

- Stancliffe RJ, Lakin KC. Analysis of expenditures and outcomes of residential alternatives for persons with developmental disabilities. Am J Mental Retard. 1997;102(6):552–568.

- Wright CJ, Colley J, Kendall E. Exploring the efficacy of housing alternatives for adults with an acquired brain or spinal injury: a systematic review. Brain Impair. 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 26]. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2019.33

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Bould E. Developing and maintaining person centred active support: a demonstration project in supported accommodation for people with neurotrauma [Internet]. Melbourne: La Trobe Living with Disability Research Centre. 2018.

- Ylvisaker M, Jacobs HE, Feeney T. Positive supports for people who experience behavioral and cognitive disability after brain injury: a review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18(1):7–32.

- Fakhoury WK, Murray A, Shepherd G, et al. Research in supported housing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(7):301–315.

- Tabol C, Drebing C, Rosenheck R. Studies of “supported” and “supportive” housing: a comprehensive review of model descriptions and measurement. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33(4):446–456.

- Cummins R, Kim Y. The use and abuse of ‘community’ and ‘neighbourhood’ within disability research: an exposé, clarification, and recommendation. Int J Dev Disabil. 2015;61(2):68–75.

- Tassé MJ, Luckasson R, Nygren M. AAIDD proposed recommendations for ICD-11 and the condition previously known as mental retardation. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51(2):127–131.

- Jones MK. Disability, employment and earnings: an examination of heterogeneity. Appl Econ. 2011;43(8):1001–1017.

- Williams MH, Bowie C. Evidence of unmet need in the care of severely physically disabled adults. BMJ. 1993;306(6870):95–98.

- Sloan S, Callaway L, Winkler D, et al. Accommodation outcomes and transitions following community-based intervention for individuals with acquired brain injury. Brain Impair. 2012;13(1):24–43.

- Beer A, Flanagan K, Verdouw J, et al. Understanding Specialist Disability Accommodation funding. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI); 2019. (Final Report No. 310).