Abstract

Purpose

An interplay of complex issues influence opportunities to gain paid work for people living with long-term conditions, but there are patterns that traverse the various contexts. Synthesising findings across qualitative studies can inform vocational rehabilitation approaches.

Methods

Public consultation and PRISMA guidelines were used to develop a protocol and comprehensive search strategy. Seven databases were searched and results screened against inclusion criteria. Included studies investigated either lived experiences of gaining paid work while living with a long-term condition or the socio-cultural factors affecting opportunities for paid work. Findings were extracted from included studies and then analysed using thematic synthesis.

Results

Sixty-two studies met inclusion criteria. Identified themes demonstrate that people living with long-term conditions need access to support through the different stages of gaining paid work. This can include considering the benefits and risks of having paid work and negotiating needs in the workplace prior to and during employment. Positive experiences for workers and employers were influential in changing attitudes about the work-ability of people living with long-term conditions.

Conclusion

Findings emphasise the interplay between socio-cultural norms and the constraints experienced in trying to gain work. Appropriately targeted support can unlock possibilities that are otherwise hindered by these norms.

Positive experiences of paid work for people living with long-term conditions and those who employ them are important for stimulating future opportunities.

“Informal” or alternative routes into paid work are experienced as more successful in contending with discrimination.

Job seekers living with long-term conditions need access to pre-placement advocacy, support to negotiate work-related needs, and support to negotiate difficulties that arise in the job.

Vocational rehabilitation initiatives need to have good collaboration with other health services to ensure consistent messages about seeking and managing work.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Background

In many societies, paid work is the main form of income for a vast majority of people. Working has been associated with health benefits related to the structure and opportunities that paid work generates, which include social acceptance and a sense of contribution [Citation1–3]. Because of these benefits, paid work is a uniquely valued form of occupation. People living with long-term conditions often experience difficulties accessing paid work due to a range of issues, many of which are linked to social attitudes and cultural beliefs about what is possible and appropriate [Citation4–8]. Aspects of what people experience can be similar across different long-term conditions when the root of the experience is not condition-specific but instead related to cultural norms and the current context of paid work and employment [Citation9]. However, the limitations attributable to the condition combined with cultural contexts or circumstances can affect what is most relevant to address for each person [Citation10–12]. While it is important that funding agencies and service providers are aware of the specific and unique issues that might affect individuals depending on their condition and context, it is also useful to analyse what is common across different conditions and across different countries. Knowledge of these common experiences can highlight where we need to concentrate efforts to address persistent barriers to work.

Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) can be a valuable component in a systematic review of qualitative research, synthesising the findings of multiple studies to generate new insights [Citation13]. Qualitative studies investigate complex lived experiences and social processes, but they are necessarily specific to the context in which they were conducted. Qualitative evidence syntheses aim to retain the in-depth and nuanced understanding of a phenomenon that is realised in high-quality qualitative research, while generating insights that span the various study contexts [Citation13]. QES may also be useful to identify new approaches to intervention that need to be tested further [Citation14]. There are various possible approaches to QES that achieve different aims [Citation15]. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Citation15] identifies thematic synthesis [Citation16] as a clear approach that is capable of producing well-developed themes, especially if applied by a team experienced in qualitative research.

There are a few existing qualitative systematic reviews that focus on paid work for people living with various long-term conditions. A recent qualitative systematic review by Esteban and colleagues [Citation17] investigated strategies people living with chronic conditions use to integrate or re-integrate into work. This review included studies about remaining in work as well as gaining work, but despite the wide criteria for work outcomes, included a relatively small number of studies in the synthesis due to a focus on European countries. Other systematic reviews on the topic of gaining or maintaining paid work have similarly focused on either a specific condition [Citation18] or specific country [Citation19]. Furthermore, studies that focus on retaining work for people who are already employed tend to emphasise what is able to be done in the workplace [Citation17], while one of the key issues for gaining work is getting access to a job and workplace in the first place [Citation20]. Therefore, there is a strong argument for investigating gaining work separately to retaining work. While a number of qualitative studies have been published that focus on gaining work, to the best of our knowledge there have been no qualitative evidence syntheses that have examined this specifically. Our aim was to focus on gaining work, looking across peer reviewed qualitative literature from a wide range of countries and cultures.

The objective for our review was to thematically synthesise qualitative research about engagement in paid work for people living with long-term conditions. We address two broad questions:

What social, cultural, and biographical factors affect opportunities for engagement in paid work for people living with long-term conditions?

What are the experiences of people living with long-term conditions with regard to gaining paid work and maintaining that work once gained?

Even in the context of rigorous systematic review methodology, it is important to acknowledge that the design of the search strategy and assessment of relevance affects what literature is accessed and included [Citation21]. Furthermore, the way that findings are reported affects if and how they are applied in policy and practice. More recent developments in systematic review design have explored explicit stakeholder involvement at key stages of the process to address external validity and transferability of findings [Citation22]. We incorporated consultation with a series of stakeholder reference groups as an aspect of the design of this systematic review (see “patient and public involvement” below).

Design of the review and synthesis

This QES was one aspect of a multi-stage systematic review of research evidence addressing support to gain paid work for people with long-term conditions. The protocol for the qualitative evidence synthesis was developed in consultation with stakeholder reference groups (see below) using the PRISMA statement [Citation23] and standardised PROSPERO protocol headings as a guide (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/). This protocol was made publicly available on Auckland University of Technology’s open access platform [Citation24], and also registered on the PROSPERO platform.

Public and patient involvement

We consulted with four stakeholder reference groups to inform the design, contextualisation and reporting of the qualitative evidence synthesis. This consultation occurred at three key stages in the process–protocol and search strategy development (including defining inclusion criteria and generating search terms), reviewing the descriptive themes prior to the development of analytic themes, and planning dissemination of findings. The reference group organisers were leaders within community organisations involved in advocacy and/or service delivery whose time was funded on the project as co-investigators. These reference group organisers engaged the members of each reference group (4–6 people per group), with the remit that each group include a balance of people with lived experience of long-term condition(s) and people involved in services and advocacy. Travel costs of all group members were covered by the project and they also received a voucher to acknowledge their time and contribution for each meeting. The four reference groups were one Māori stakeholder reference group (Indigenous culture of Aoteaora New Zealand) and three condition-specific stakeholder reference groups (mental health, amputation and progressive neurological conditions). The various conditions for the condition-specific groups were purposively sampled, aiming to achieve diversity with regard to the types of challenges that people might experience in relation to paid work.

Definition of terms for search and inclusion

We used a pre-planned, comprehensive database search strategy specifying keywords and subject terms adapted for each database. The keywords were generated based on a discussion of terminology and language with our stakeholder reference groups which covered included populations, phenomena of interest and what might be offered by various study designs. Applicability of each study to one or more of the research questions was key to inclusion at full text review. Key definitions in terms of eligibility for inclusion are summarised below. Detailed inclusion criteria are given in the study protocol [Citation24].

Included populations

The review included studies where participants were sixteen years of age or older, who had a long-term condition and were not in paid work at study outset. We considered someone with a long-term condition to be a person living with effects of an injury, illness or health condition that are expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

Included phenomena

We were specifically interested in experiences regarding trying to gain and maintain paid work. This included the experiences of people living with long-term conditions and also analyses of the socio-cultural conditions that shape what is possible for those people. Paid work was defined as commencement of either full- or part-time paid work as defined in the Resolution concerning statistics of the economically active population, employment, unemployment and underemployment, adapted by the Thirteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (October, 1982) [Citation25] or commencement of legal occupation that generates a livelihood (e.g., Indigenous practices that generate resources to live on but are not paid employment). Although unpaid work is also important and of interest for this population, we considered it to be significantly different to the paid work context to warrant specific and separate analysis.

Included study designs

We considered all qualitative study designs potentially appropriate to addressing the review questions. This included but were not limited to qualitative descriptive, ethnographic, grounded theory, critical, indigenous and post-structural methodologies. Qualitative evidence syntheses were not eligible for inclusion as there would be potential overlap between these and the other included studies. Where there were several reports on the same study, we included what was needed to provide all eligible findings. For example, a thesis or dissertation would be included and papers based on the thesis or dissertation would be excluded because they covered the same findings in less detail.

Timeframe

We specified a 15-year timeframe for study eligibility due to fast-changing job market conditions, and to ensure the policy environment with regard to employment support structures and funding was as contemporary as possible.

Sources of research reports

We searched seven databases for peer reviewed articles, theses and dissertations for study reports published between 1 January 2004 and 28 March 2019. These databases were MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), PsychINFO (OvidSP), AMED (OvidSP), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Proquest Dissertations and Theses database and Business Source Complete (EBSCO). Search strategies were designed and tailored to each database using key words and subject heading terms.

Study quality

A high level of study quality was important for inclusion of studies for data extraction as we wanted to ensure that only the findings of studies that were absent of critical quality concerns were included for thematic synthesis. We considered these critical quality criteria to be appropriate methodology, appropriate design, appropriate data collection, sufficiently rigorous analysis and clear statement of findings.

Study screening

One search and screening process was applied to identify eligible studies for the two questions reported in this paper and also a third question not reported in this paper which focused on experiences of vocational rehabilitation and employment support services. The team involved in study screening and subsequent quality assessment included three PhD-qualified and experienced qualitative researchers with expertise across vocational rehabilitation (JF), mental health and occupation (KR), social disadvantage (DA, KR, JF), rehabilitation and disability (JF, KR), with input from the methodological lead for the study (WL), who was experienced in qualitative research and conducting Cochrane reviews related to rehabilitation. Study inclusion depended on the study meeting inclusion criteria specified in the pre-published protocol and addressing one or more of the research questions. Two review authors independently considered the titles and abstracts from the studies identified and screened for qualitative methodologies and relevance to the research questions. Full text screening was carried out for all studies that were identified as possibly meeting inclusion criteria at title and abstract screening. Disagreement or uncertainty about relevance at any stage was resolved through consideration and discussion of full study reports, involving a third review author where necessary. This process involved three authors (JF, DA, KR) and was managed using Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, www.covidence.org).

Quality assessment

All studies that met the scope of one or more of the questions were assessed for methodological quality using Sections A and B of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist [Citation26]. Section A (six items) assesses the study design as it affects validity of results. Section B (three items) addresses the reporting of results directly. Section C was not included in quality assessment for this qualitative evidence synthesis as it focuses on external validity, which is specific to the local context where the study is to be applied.

Each item was scored “yes,” “no” or “can’t tell.” Where the consensus answer to a question addressing appropriate methodology, appropriate design, appropriate data collection, sufficiently rigorous analysis or clear statement of findings (our critical quality items–see “study quality” eligibility above) was “no,” that study was excluded from data extraction. “Yes” to all of these questions was considered essential for confidence in the reported findings.

Where an answer was “can’t tell” and the information was critical to quality assessment, study authors were contacted for further information. If they could not be reached or could not provide the requested information, the study was excluded from data extraction.

Data extraction

Included studies were categorised by consensus according to their primary focus (socio-cultural factors or lived experiences). For each study, we then extracted the following available data: full citation, corresponding author, year published, country, data type (e.g., interview), sample size, theoretical orientation (e.g., social constructionist), type of method (e.g., grounded theory), types of participants (e.g., person with condition), condition (e.g., spinal cord injury), gender and culture of participants, and study findings. The data for analysis for each study was the extracted text from the “results” or “findings” sections.

Thematic synthesis

Synthesis of study findings to address our research questions followed the process of “thematic synthesis” described by Thomas and Harden [Citation16]. We used QSR International’s NVivo software for data management during coding, but thematic development was recorded using a mixture of word processing documents, tables and hand-written notes. JF led the coding and development of descriptive themes from the studies that were categorised as having a socio-cultural focus, being most experienced with critical and post-structural study designs. DA led the coding and development of descriptive themes from the studies that were categorised as focused on lived experiences, being experienced with descriptive and interpretive study designs. Coding was inductive, in which each segment of text was attributed codes which represented its content and meaning. Over the course of coding the studies, a bank of codes was built up and adjusted in an ongoing process to reflect the material held within each code. As part of our coding process, we explicitly noted differences relating to condition or local context where pertinent. Code description and content was discussed and debated among the first three authors at regular meetings with reference to the contributing study findings. This was to test assumptions, challenge interpretations and raise questions. Once we had completed coding, the team grouped and organised the various codes into descriptive themes for the next stage of the process.

Descriptive themes for each category (socio-cultural influences and lived experiences) were presented in stakeholder reference group meetings for discussion and debate, often referring back to the findings of the primary studies but also initiating an exploration of the relationship between the descriptive themes and the research questions for the synthesis. It was clear from these discussions that the descriptive themes focused on socio-cultural influences often helped contextualise and understand the descriptive themes focused on lived experiences. These discussions enabled the research team to develop the analytic themes which are more theoretically driven–considering how the various descriptive themes contribute to and challenge each other, therefore going beyond the findings of the primary studies to address the synthesis-focused research questions. The analytic themes that we report here address both research questions together, as treating the questions as two aspects of a larger whole provided richer analytic themes than would have been possible if we had kept them separated.

Findings

Search results

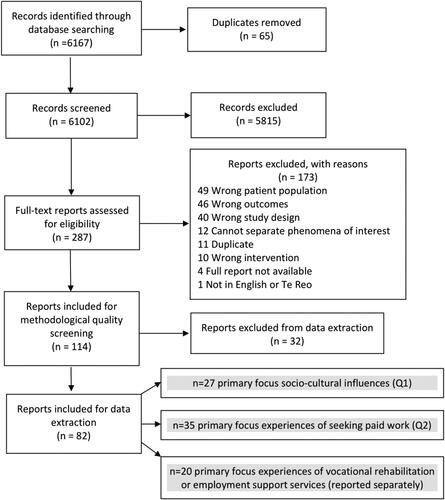

The database search identified 6102 records for title and abstract screen (after removing duplicates). Of these, 287 were eligible for full-text screen. After full text review, we had 114 studies fitting the scope of one or more of the questions. Following methodological quality screening, 82 studies contributed to the qualitative synthesis across three research questions (28% excluded based on quality assessment). Of the 82 studies, 27 studies addressed question one, and 35 studies addressed question two reported in this paper. There were also 20 studies that addressed the third question about experiences of services (reported separately). shows the PRISMA flowchart.

Characteristics of included studies

Detail of contextual characteristics of studies is provided in . All the studies that were included in the review scored “yes” on all our critical quality questions (see above), meaning that we had high confidence in the reported findings. Studies that scored higher on our non-critical questions generally had richer or more nuanced findings than lower scoring studies, meaning that they naturally contributed more to the findings of the synthesis.

Table 1. Contextual characteristics of studies.

Studies focused on social, cultural and biographical factors affecting opportunities for paid work

The first group of studies focused on the influence of wider society–i.e., the social, cultural and biographical factors that affected opportunities for paid work for people living with a long-term condition. Twenty-seven qualitative studies focused on this topic. These studies were from 10 different countries, with a fairly even distribution of publication dates between 2004 and 2019. Data collection used a variety of methods including interviews, focus groups and document analysis. Study participants included people living with a long-term condition, service providers, policy makers, employers and families. A range of methodologies were used; including grounded theory, post-structural discourse analysis and qualitative descriptive.

Studies focused on experiences trying to gain paid work and maintain new work for people living with a long-term condition

The second topic of inquiry for the qualitative evidence synthesis was about the experiences that people living with long-term conditions had when they tried to obtain paid work, and maintain that work once they were in a job. Thirty-five qualitative studies contributed to this question. These studies were from 12 different countries, with a fairly even distribution of publication dates between 2004 and 2019. Interviews with people living with a long-term condition was the most common method of data collection. Some also used focus groups, and a few studies also included support people or service providers as participants. Most studies used a qualitative descriptive methodological approach.

Thematic synthesis: socio-cultural context and experiences trying to gain and maintain paid work

The themes from the synthesis focus on both personal experiences of trying to gain and maintain paid work in the context of living with a long-term health condition and the broader socio-cultural influences on those experiences. Initially, we discuss the influence of the person’s psychosocial context such as their family and community context, and the fears identified in the included studies that people have about possibly being worse off with employment. Workplace accessibility is discussed next, leading into a discussion of the broader accessibility of work–the neoliberal employment conditions under which skilled work and high productivity have become increasingly expected. The next theme identifies the flipside of the neoliberal job market, in which flexible work structures and employment practices make “non-standard” work arrangements possible, and the following theme considers routes into employment and how people living with long-term conditions in the included studies discussed them. The next two themes discuss what people contend with once a position is identified, including negotiating disclosure and rights. The final theme brings together aspects of the prior discussions, identifying how the experiences of a range of stakeholders are instrumental in influencing beliefs and attitudes. We pinpoint this final theme as key in identifying possibilities for effecting positive change. We have given comprehensive references to the original studies but not specific quotes to support our thematic reporting. The themes are often constructed from multiple points of reference per study and across multiple studies, and the nature of analytic themes is that in synthesising many studies, they aim to “go beyond” the findings of the primary studies–key to the original contribution of a synthesis [Citation16, p. 7]. As they are published studies, the original data is available in full. The full list of references for studies that contributed to the synthesis for each topic is provided as online Supplementary Material.

The significant impact of a person’s psychosocial context

Across studies, there was emphasis that although people want to have the opportunity to work, the reality of living with a long-term condition should not be minimised. People discussed negotiating issues such as reliance on other people, including carers, in order to be a “presentable,” “employable” person [Citation4,Citation27]. Furthermore, the time and energy associated with managing the condition could impede availability and energy for paid work [Citation4,Citation28,Citation29], an issue that could go unrecognised by employment support services [Citation28]. Significant others such as partners and families had to negotiate their shared lives, and many had concerns about the possible effects of paid work for the person with the long-term condition, for example increased stress on life outside of work, or exacerbation of the condition [Citation9,Citation27,Citation30–32].

Everyday messaging from family and friends informed how job seekers with a long-term condition felt about their own capacity to find and maintain employment [Citation33–37]. Support from personal relationships was especially important to people transitioning into employment from institutions such as hospitals [Citation35] or who had been out of work for extended periods [Citation38]. Such support could be pivotal for perseverance in the face of disappointments in trying to obtain work [Citation38], and the support from personal relationships could more generally assist with positive reintegration into working life [Citation33,Citation37]. One study in particular illustrated how strong and explicit family messaging regarding expectations to work had a strong influence on study participants’ drive to support themselves through paid employment [Citation34]. Role models who also live with long-term conditions provided exemplars and encouragement for keeping up momentum towards finding and maintaining paid work [Citation34].

Individual social and cultural conditions also had an effect on what was possible and comfortable. For example, one study identified differences in opportunities in small communities due to close-knit lives (e.g., discrimination being more ingrained and enduring in the community) [Citation30]. Where people could hide impairments, often they did. People who could not hide their impairment often feared judgement based on appearance [Citation4,Citation30,Citation39]. Past experiences often affected confidence and belief in abilities–where prior discrimination produced negative expectations [Citation4,Citation32,Citation40]. Situations that made it more acceptable to be inter-dependent (such as being female) were reported to make it easier to ask for workplace accommodations or help [Citation27,Citation32].

The risk (and fear) of being worse off with employment

Poverty can be a significant barrier to employment opportunities [Citation9,Citation30,Citation40]. Poverty prevented access to appropriate resources to turn up on time or to present appropriately at work. Threatened poverty was associated with fear of losing benefits when work begins, with no guarantee that work will “work out.” This perception of threat could be intensified by “horror stories” and personal experiences of problems with automatic benefits system errors and difficulty qualifying for benefits, creating an investment in staying “safe” rather than risking employment [Citation40]. Income support was often tied to other benefits like medical entitlements or housing, which people cannot afford to lose [Citation40]. Some people navigated this by working in part-time jobs which they were overqualified for so they could earn lower wages that did not interfere with benefits or medical cover [Citation33,Citation41,Citation42]. However, even working part-time, some people found themselves with decreased financial security as a consequence of gaining employment [Citation33].

Accessibility of the workplace and the work environment

Accessibility of workplaces came through as a central concern for people with long-term conditions who were seeking work [Citation43,Citation44]. Within the workplace, even when accessibility was made possible through devices, malfunctioning of technologies such as lifts impacted on job accessibility [Citation43]. Transportation to work was often problematic, particularly for people with a spinal cord injury [Citation20,Citation42], multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy [Citation20], and traumatic brain injury [Citation44] due to restrictions on ability to drive. To be a viable opportunity, a potential job needed to be geographically accessible and able to be reached within a reasonable amount of time [Citation20]. The necessity of using public transport or relying on friends and family introduced concerns regarding timeliness and reliability, particularly for those who resided in rural areas [Citation20,Citation42,Citation43]. In the face of transport challenges, some people opted to look for roles where they could work from home [Citation42].

Disadvantage within neoliberal (market-driven) employment conditions focused on skilled work and super-productivity

Many studies discussed how the job market determined employment possibilities for people with long-term conditions [Citation4,Citation9,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation45–47]. The employment market included the jobs available, but also the broader expectations of work culture. One example relating to jobs available was that low-skilled labour jobs in the “secondary labour market” have long been considered a stable employment opportunity for people who experience disability or mental health conditions because of being able to learn a specific job and master it [Citation31]. However, these types of employment opportunities are becoming much rarer in westernised countries [Citation47]. A culture of skilled work and “super-productivity” is becoming more and more of a pressure across industries. This includes unwritten rules requiring more than an employment contract specifies to actually meet basic job requirements, which marginalises people who manage a long-term condition [Citation4,Citation9,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation45–47].

There was a misfit reported between the reality of living with a long-term condition and what is assumed necessary in a worker. This was perpetuated in vocational rehabilitation services, where the logic was that a person’s condition needed to be stable or improving to gain employment, whereas many people with long-term conditions may experience periods of unstable or deteriorating health status [Citation28]. Even with more stable long-term conditions, there can be a period of time during which a person is adjusting to their abilities. This sometimes delays vocational support services instead of providing assistance to negotiate circumstances and adjust to current abilities [Citation28,Citation29].

Vocational services need to acknowledge the reality of living with long-term conditions and the effect this may have on ability to seek competitive employment [Citation28]. Forced engagement with vocational services could be experienced as degrading and perceived as a lack of acknowledgement of personal circumstances [Citation4,Citation28]. Similarly, generalist employment services where staff lacked knowledge of the condition(s) their clients live with could lead to inappropriate assessment and service provision [Citation30,Citation40].

Positive influence of more flexible work structures and employment practices on work-ability

Some studies emphasised a positive effect of neoliberal employment culture, in that the job market was not fixed, but could be negotiated. Situations were found in which disability could be insignificant to worker value, lived experience could be valued as a qualification for a job, or worker value could be argued in conversation with an employer [Citation4,Citation32,Citation45,Citation46]. This negotiation was impeded in situations where there was a “standard” job description and person specification, because this is based on a disembodied “standard” worker [Citation28,Citation30,Citation47]. Studies reported that where people with long-term conditions are able to get involved in job development, or a flexible interdependent work culture is present, this promotes inclusion [Citation30,Citation32,Citation47].

Appropriate support for people with long-term conditions to gain employment was multi-faceted and systems set up to address gaining employment needed to be realistic about what is required. Basic access to education and transportation were reported as key factor in allowing people the possibility of work [Citation9,Citation27,Citation30–32,Citation40,Citation48]. Accessible workplaces were also key [Citation9,Citation32,Citation48]. It was also crucial that employment support focused on a person’s work-ability (rather than disability) on an individual level, but also addressed wider social and cultural barriers [Citation32,Citation47]. When there was limited resource, studies reported that the focus stayed at the level of individuals, because cross-sector efforts are required to overcome larger societal barriers [Citation30,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49]. Similarly, studies reported that integration of employment support with health services facilitated effective practice–as long as it was truly collaborative [Citation30,Citation40]. Vocational support is often not a skillset of health professionals and employment not a priority in resource-limited health services [Citation30,Citation40]. However, work-ability needed to be taken into account in treatment decisions (like drug prescription) and positive messaging about work options needed to be consistent [Citation28,Citation39].

Reliance on “informal” or alternative routes into employment to contend with discrimination and increase confidence in work-ability

Studies reported that the main assumption in the context of employment (across employers, support networks and people living with long-term conditions) was that a long-term condition will negatively affect ability to do the job [Citation4,Citation9,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation45–47,Citation50]. Because of these dominant abelist discourses, there was a vicious cycle of people living with long-term conditions being out of work [Citation30]. Those who wanted to work had to navigate an automatic negative assessment of their condition on work-ability. They worked extra hard to become “employable”–for example doing training and gaining experience well in excess of what a peer without a long-term condition would do [Citation4,Citation9,Citation29,Citation32,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48,Citation51]. They also reported hiding disabilities or problems they experience at work in order to “prove” their work-ability [Citation30,Citation32,Citation45]. However, these strategies can actually reinforce discourses that marginalise people with long-term conditions in the workplace because they emphasise the perception that people do not work if they experience difficulties managing “normal” work conditions [Citation28]–perpetually re-creating the problem.

Networking was reported to be a successful approach, as discussions with potential employers could emphasise people’s skills and reputation rather than the condition being a focus in negotiations, or a ‘surprise’ first impression [Citation52]. Conversely, “mainstream” routes to employment such as searching employment websites and databases, sending out and following up on resumes and using government-run job centres were reported to be energy and time consuming, with limited success for acquiring work [Citation53].

Facing condition-related changes in abilities, some people chose to retrain, or learn to use assistive technologies [Citation52,Citation54]. They sought courses that could help them to renew old skills or learn skills for entirely new fields. Sometimes retraining was based on a personal interest [Citation44], but more often was based on the limited vocational options presented to them [Citation52]. Some participants found they were able to draw on interests to inform their job choices, but many felt they had limited viable opportunities [Citation44]. People who had spent a lot of time out of work, or spent time in an institution or hospital experienced low self-belief and work aspirations, and anticipated discrimination from employers [Citation35,Citation53]. People who lacked confidence in work-ability discussed gradually introducing themselves back into the workforce with caution. Graduated approaches including voluntary or part-time paid work for example, helped to develop a sense of achievement and positivity toward their future in the workplace [Citation35,Citation53]. Engaging in internships was also a useful way for people to acquire a sense of confidence and positive workplace expectations, as well as building their repertoire of work skills [Citation34].

Negotiating disclosure: need for workplace accommodation versus fear of discrimination

Willingness to tell an employer about having a long-term condition varied person-to-person, as did reported responses. Some people feared disclosing this to prospective employers because they anticipated discrimination that might limit their chances of securing employment [Citation55,Citation56] or interfere in their social inclusion with co-workers [Citation37]. People with mental health conditions were particularly hesitant, anticipating perceptions from employers and co-workers that people with mental health conditions are unreliable, unpredictable [Citation37], or violent [Citation57].

Many people felt they had no choice but to disclose their condition(s) to explain gaps in their work history [Citation54], or found that disclosure was an inevitable part of meeting an employer through supported employment programmes [Citation55]. People who had multiple conditions sometimes considered partial disclosure, disclosing a more obvious or “socially acceptable” condition in order to secure workplace accommodations which could help the work with all their conditions, both disclosed and undisclosed [Citation37]. Personal knowledge of their own rights regarding disability often helped in securing accommodations, particularly in framing accommodations as a right, not simply as a request [Citation52].

For some jobs, people reported there was advantage in disclosing their conditions [Citation37,Citation55], particularly if looking for employment as peer mentors or counsellors, as “lived experience” in these jobs was considered to contribute to their qualification for the job [Citation37]. In some cases, employers responded favourably to disclosure, which they followed up by discussion regarding possible job accommodations [Citation36,Citation37,Citation55]. An employer knowing about their long-term condition could also put employees in a better position to negotiate workplace accommodations [Citation37]. Some people delayed disclosure until they had secured work [Citation36]. However, in some cases, once they had disclosed people felt that they were expected to work harder than their co-workers to “prove” their competence, or feared that their employment could be terminated if they showed any condition-related limitation [Citation37]. Even having gained employment, some people chose not to disclose for fear that doing so might jeopardise their employment [Citation55,Citation58]. Among those who elected not to disclose, some reported having to fabricate stories to explain gaps in their work histories [Citation37].

Contending with rights and fear of discrimination in the workplace

In some cases, people tolerated difficult conditions to maintain work, given the difficulty of finding a job in an accessible location or the concern of not knowing what other work options they might have [Citation55]. Studies indicated it was relatively common for people with long-term conditions to tolerate anxiety around struggles with daily commuting, or fear of discrimination in the workplace [Citation56]. One study described people tolerating difficult working conditions–such as monotonous or boring work, unsupportive or discriminatory work environments, high levels of stress and anxiety, limited pay, and working long hours without breaks [Citation55]. Some people did not want to draw attention to the fact that they experienced difficulties or may have been afraid to ask for accommodations [Citation52,Citation59]. People feared losing opportunities for sustained full-time employment by asking for “special treatment” [Citation59, p. 128] or had learned to be cautious because of experiences of negative attitudes from employers in the past [Citation52].

Studies of good employment that was successfully maintained highlighted the difference that appropriate workplace accommodations could make to work life [Citation52,Citation60]. One study presented several cases in which employers recognised and considered responses to challenges presented by a worker’s long-term condition [Citation44]. These cases ranged from requesting quiet office spaces or frequent coffee breaks in response to attention difficulties, to establishing daily routines in response to issues with short-term memory [Citation44]. In one study, these cases were contrasted with the worsening functioning of people whose conditions are not taken into account in relation to the duties of their employment [Citation44].

Experiences as instrumental in influencing beliefs and attitudes

One of the most important things that changed or influenced beliefs about working with long-term conditions were actual experiences. Various studies discussed this in relation to both employers and people seeking work.

For employers, one of the important issues was in relation to perceived risk. Concerns were about workplace safety risks in the present, and future risk if an employee turned out to be unreliable or unable to do the job [Citation4,Citation9,Citation27,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation45–47,Citation50]. This was particularly acute when a potential employee had a long-term condition that was (or was perceived to be) unstable or deteriorating [Citation39,Citation40,Citation46,Citation50]. Concerns about risk negatively affected hiring decisions, but employment support and advocacy services were seen as a “safety net” by employers in some studies, and it was mainly experiences with people with long-term conditions in the workplace that shifted employer beliefs and expectations [Citation31,Citation32,Citation50]. Some employers were open to or motivated to create opportunities, but needed advice and assistance from vocational specialists [Citation30,Citation47]. Services like advocacy and job development were helpful in these situations, particularly when they sought to understand the employer’s perspectives and concerns that were particular to their industry and workplace [Citation9,Citation27,Citation30,Citation46,Citation47].

Employers sometimes identified unexpected positive effects of more diverse hiring such as workplace accommodations put in being helpful for other employees [Citation46,Citation50], or feeling like they were accessing an “untapped resource” of skilled people with long-term conditions [Citation50]. One study identified that having other disabled people in the workplace during induction meant new employees could be shown alternative ways of doing things that may be more suited to their particular abilities [Citation51].

Some employers talked about how they made their workplace more welcoming to people who experience disability. This included encouraging a culture of disability disclosure (so that people expected and welcomed this), leading by example so that co-workers would be positive towards colleagues who experience disability, and actively considering what might be comfortable for different types of people in the workplace, not assuming everybody is the same [Citation31,Citation46,Citation49]. The creation of mentoring opportunities was also seen to be important in terms of creating positive experiences for multiple parties [Citation4,Citation46,Citation49].

Employers were sometimes motivated to hire people who were identified as disabled because of incentive programmes or legal requirements [Citation4,Citation31,Citation40], or because of a belief that it was a socially responsible thing to do [Citation4,Citation30–32,Citation39,Citation46,Citation47,Citation50]. Some ideas of “social responsibility” were genuinely driven by a want to create opportunities for people, and sometimes it was more related to outward appearance. For example, some employers were reported to be concerned that having employees with “invisible” disability did not afford them the appearance of social responsibility as an organisation [Citation40]. It was not clear from the current research if the experience gained through incentive programmes shifted the attitudes of the more appearance-driven organisations.

Beliefs and expectations about work-ability from people with long-term conditions were also influenced and shifted by experiences. Having opportunities to test out abilities and show competence and/or go into discussion with an employer about what would work best to enable the person to do the job were reported to have a positive impact on confidence in work-ability [Citation4,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation45,Citation47]. Messages (explicit and implicit) from health and vocational services could serve to increase or reduce confidence in ability to work [Citation39,Citation60]. Beliefs about long-term conditions and work were communicated very early on from health professionals–either encouraging or discouraging (sometimes throwaway comments). These beliefs from “experts” influenced the person with the condition in their confidence to work with a long-term condition. Health professionals had opportunities particularly in the early stages of a person adjusting to a new condition where they could challenge existing negative assumptions about work and disability by initiating work-related conversations [Citation29]. Benefits systems discussed in many studies communicated mixed messages about work-ability–on the one hand encouraging engagement with vocational rehabilitation, but on the other making it very difficult to qualify for disability benefits, meaning that people became invested in qualifying for the benefit [Citation9,Citation30,Citation40].

Employment support service providers and funders were also implicated in the experiences of employers and people seeking work. Providers responded to changes in funding and service directives by adapting services to achieve what they needed to survive financially and politically [Citation30,Citation40,Citation61]. It was reported that a focus on placement quantity led to situations where providers worked with less diverse clients and were less inclined to seek a good match between work placement and client need [Citation30,Citation40]. Poorly-matched placements could affect longer-term employment and employability [Citation30,Citation40]. In combination with the above discussion about experiences influencing beliefs, this is an important consideration when it comes to opportunities and confidence.

Similarly, studies that focused on policy showed that resourcing for support in employment needed to reflect what might be required to achieve success. This included working with employers to provide appropriate workplace accommodation and education, and follow-on support [Citation9,Citation30,Citation32,Citation39,Citation40,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50]. Follow-on support may include job-related coaching, strategy development and adaptation, equipment, accommodations and condition-related needs (like time for medical appointments or mental health support that is relevant to the employment setting). In situations where appropriate support was lacking, it is likely this could affect placement success and also future employment opportunities and willingness [Citation30].

Discussion

This qualitative evidence synthesis highlights several key issues and also significant opportunities in supporting people who live with long-term conditions to access and maintain paid work. Messages about what is expected and possible from health and social care professionals have major influence, and prior experiences in each person’s interpersonal networks will have an effect on what they think is realistic or even possible.

Negotiating disclosure was a key issue, given that in the current time there is a dominant perception that people living with long-term conditions cannot work. There is a role here for advocacy and support. Findings indicated that disclosure is important for a range of reasons, but perhaps it could be conceptualised in a less negative way. The language of “disability disclosure” could detract from discussion of more positive strategies. Some examples from the literature included workplace cultures of sharing relevant information about accommodation needs and promoting interdependent workplaces. At an individual level, a paper by Heilscher and Waghorn offers a discussion on this, suggesting that health and vocational practitioners conceptualise it more broadly as “managing disclosure of personal information” [Citation62, p. 306], which we all do in employment.

Creating successful experiences for all stakeholders came through as having a major impact on influencing what is possible. It is actually having people with long-term conditions visibly in paid work and coping with appropriate accommodations that will help change attitudes and address stigma. Positive experiences for all stakeholders feed through into more opportunities and openness to possibilities. There was a clear message about the importance of appropriate workplace supports and accommodations, for a number of reasons. At the time when people are beginning work, the new work can often feel like a fragile situation, and managing this well enables a longer-term positive impact associated with well-matched and well-supported job opportunities. Good experiences for the stakeholders involved (workers, employers, health professionals and families, etc) are likely to result in more opportunities and shifts of attitudes in the future.

Accessibility, including from lack of money for job-seeking basics such as transportation and interview attire, along with fear of financial hardship coming off benefits were real barriers to seeking paid work. This means there is a need for active consideration of the way in which benefits are managed. This may include consideration of explicit measures to safeguard people who want to try work, and clear and accurate advice on benefit entitlements and abatement.

There were reports of people tolerating poor working conditions or having strategies for coping with work that compromised other parts of their lives. These are particularly important to think about in terms of advocacy and support. Support services need to be aware of the ways people cope and be able to support them to make informed decisions about how to manage, including considering possibilities such as further negotiation within the workplace (perhaps through an advocate). In the longer term having more visibility of people working with long-term conditions may help to mitigate some of these issues.

Finally, findings highlighted that service providers do what they are rewarded for–be that funding or acknowledgement or both. For funders, it is important to periodically analyse what is being rewarded and check that it is in line with the intent of the system, and in line with current evidence about what achieves the outcomes sought.

This was a rigorous systematic review informed by consultation with stakeholders. Our method involved excluding studies of low quality (28% of all studies read as full text papers), ensuring that only studies of moderate to high quality were included in the review. Due to the time and work involved in selection, data extraction and synthesis, we have not updated the search since 28 March 2019, and this is a limitation of the study findings. Based on a recent search we estimated that (before quality assessment) approximately 15 studies meeting our protocol inclusion criteria were published between the last search date and 10 August 2020, when the article was finalised. Assuming a similar rate of inclusion after quality assessment, this would translate to approximately 8 studies that relate to the two questions reported in this article. It would not be appropriate to discuss the findings of new studies without updating the thematic synthesis.

A majority of studies that met inclusion criteria for this review focused on mental health conditions. There is a need for more studies that are focused on people living with other categories of conditions such as physical and neurological conditions. Although we did find research that addressed people with conditions such as cancer and people living with HIV/AIDS, very often this research was out of scope for our review because it focused on return to existing employment. There is a gap here in relation to research on support for gaining new work. Regarding geographic location, there is a clear need for more studies conducted in regions outside of North America and Scandinavia. Our stakeholder reference groups did not include family or employers, and it would be a useful perspective to include in future reviews of this type. Finally, our stakeholder reference group that focused on Indigenous perspectives highlighted was that there was no research contributing to this qualitative synthesis that looked at Indigenous perspectives or used Indigenous research methods. This is a major gap in the knowledge base that has contributed to this synthesis, and we have no information about whether or not these findings are transferable to or appropriate for Indigenous peoples. It is critical that this gap is addressed given current economic and health inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Supplementary_Material.docx

Download MS Word (20.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Thank you to the leads of the stakeholder reference groups who contributed to this work: Dr. Helen Lockett, Sean Gray, Dr. Matire Harwood, Neil Woodhams; and also to the contributors in the stakeholder reference group meetings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australasian Faculty of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. Realising the health benefits of work: a position statement. Sydney: The Royal Australasian College of Physicians; 2010.

- Jahoda M. Employment and unemployment: a social psychological analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1982.

- McKee-Ryan F, Song Z, Wanberg CR, et al. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(1):53–76.

- Fadyl JK, Payne D. Socially constructed ‘value’ and vocational experiences following neurological injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(22):2165–2177.

- Harlan SL, Robert PM. The social construction of disability in organizations. Work and Occupations. 1998;25(4):397–435.

- Louvet E. Social judgement toward job applicants with disabilities: perception of personal qualities and competencies. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52(3):297–303.

- Pacheco G, Page D, Webber DJ. Mental and physical health: re-assessing the relationship with employment propensity. Work Employ Soc. 2014;28(3):407–429.

- Schur LA, Kruse D, Blasi J, et al. Is disability disabling in all workplaces? Workplace disparities and corporate culture. Ind Relat. 2009;48(3):381–410.

- Lindsay S, McDougall C, Menna-Dack D, et al. An ecological approach to understanding barriers to employment for youth with disabilities compared to their typically developing peers: views of youth, employers, and job counselors. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(8):701–711.

- Brannelly T, Boulton A, Te Hiini A. A relationship between the ethics of care and māori worldview—the place of relationality and care in maori mental health service provision. Ethics Soc Welf. 2013;7(4):410–422.

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625.

- Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q. 1999;77(1):77–110, iv-v.

- Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000882.

- Levack WMM. The role of qualitative metasynthesis in evidence-based physical therapy. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17(6):390–397.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J., et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019): Cochrane. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- Esteban E, Coenen M, Ito E, et al. Views and experiences of persons with chronic diseases about strategies that aim to integrate and re-integrate them into work: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):1022.

- Sweetland J, Howse E, Playford ED. A systematic review of research undertaken in vocational rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2031–2038. PubMed PMID: 22468710; English.

- Clayton S, Bambra C, Gosling R, et al. Assembling the evidence jigsaw: insights from a systematic review of UK studies of individual-focused return to work initiatives for disabled and long-term ill people. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):170.

- Graham C, Inge K, Wehman P, et al. Barriers and facilitators to employment as reported by people with physical disabilities: an across disability type analysis. J Vocat Rehabil. 2018;48(2):207–218.

- Clegg S. Evidence‐based practice in educational research: a critical realist critique of systematic review. Br J Sociol Educ. 2005;26(3):415–428.

- Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a protocol for a systematic review of methods, outcomes and effects. Res Involv Engagem. 2017;3(1):9.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269.

- Fadyl JK, Anstiss D, Reed K, et al. Protocol: support for gaining employment for people with long-term conditions–qualitative systematic review. Auckland: Tuwhera Open Research, Auckland University of Technology; 2019.

- ILO. Resolution concerning statistics of the economically active population, employment, unemployment and underemployment. Geneva: International Labour Organisation; 1982.

- Public Health Resource Unit. Critical appraisal skills programme: making sense of evidence [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2007 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.phru.nhs.uk/casp/casp.htm

- Lindsay S, Cagliostro E, Albarico M, et al. Gender matters in the transition to employment for young adults with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(3):319–332.

- Patel S, Greasley K, Watson PJ. Barriers to rehabilitation and return to work for unemployed chronic pain patients: a qualitative study. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(8):831–840.

- Ville I. Biographical work and returning to employment following a spinal cord injury. Sociol Health Illn. 2005;27(3):324–350.

- Gruhl KLR. An exploratory study of the influence of place on access to employment [PhD thesis]. Sudbury: Laurentian University; 2010.

- Huang I-C, Chen RK. Employing people with disabilities in the Taiwanese workplace: Employers’ perceptions and considerations. Rehabil Counsel Bull. 2015;59(1):43–54.

- Ramos M. A qualitative study of a job placement system for people with disabilities [PhD thesis]. Austin: University of Texas; 2007.

- Koch L, Egbert N, Coeling H, et al. Returning to work after the onset of illness: experiences of right hemisphere stroke survivors. Rehabil Counsell Bull. 2005;48(4):209–218.

- Olney M, Compton C, Tucker M, et al. It takes a village: influences on former SSI/DI beneficiaries who transition to employment. J Rehabil. 2014;80(4):28–41.

- McQueen J, Turner J. Exploring forensic mental health service users’ views on work: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Br J Forensic Prac. 2012;14(3):168–179.

- McRae P, Hallab L, Simpson G. Navigating employment pathways and supports following brain injury in AUstralia: client perspectives. Aust J Rehabil Couns. 2016;22(2):76–92.

- Goldberg SG, Killeen MB, O’Day B. The disclosure conundrum: how people with psychiatric disabilities navigate employment. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2005;11(3):463–500.

- Mettavainio B, Ahlgren C. Facilitating factors for work return in unemployed with disabilities: a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2004;11(1):17–25.

- Krupa T, Kirsh B, Cockburn L, et al. Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work. 2009;33(4):413–425.

- Gewurtz RE. Instituting market-based principles within social services for people living with mental illness: the case of the revised ODSP employment supports policy [Doctoral Dissertation]: Toronto: University of Toronto; 2011.

- Paul-Ward A, Kielhofner G, Braveman B, et al. Resident and staff perceptions of barriers to independence and employment in supportive living settings for persons with AIDS. Am J Occup Ther. 2005;59(5):540–545.

- Cotner B, Njoh E, Trainor J, et al. Facilitators and barriers to employment among veterans with spinal cord injury receiving 12 months of evidence-based supported employment services. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21(1):20–30.

- Hernandez B, Cometa M, Velcoff J, et al. Perspectives of people with disabilities on employment, vocational rehabilitation, and the Ticket to Work program. J Vocat Rehabil. 2007;27:191–201.

- Macaden A, Chandler B, Chandler C, et al. Sustaining employment after vocational rehabilitation in acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(14):1140–1147.

- Fadyl J, McPherson K, Nicholls D. Re/creating entrepreneurs of the self: discourses of worker and employee ‘value’ and current vocational rehabilitation practices. Sociol Health Illn. 2015;37(4):506–521.

- Henry AD, Petkauskos K, Stanislawzyk J, et al. Employer-recommended strategies to increase opportunities for people with disabilities [Empirical study; interview; focus group; qualitative study]. J Vocat Rehabil. 2014;41(3):237–248.

- Kirsh B, Krupa T, Cockburn L, et al. A Canadian model of work integration for persons with mental illnesses. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(22):1833–1846.

- Kim MM, Williams BC. Lived employment experiences of college students and graduates with physical disabilities in the United States. Disabil Soc. 2012;27(6):837–852.

- Lindsay S, Cagliostro E, Leck J, et al. Employers’ perspectives of including young people with disabilities in the workforce, disability disclosure and providing accommodations. J Vocat Rehabil. 2019;50(2):141–156.

- Phillips BN, Morrison B, Deiches JF, et al. Employer-driven disability services provided by a medium-sized information technology company: a qualitative case study. J Vocat Rehabil. 2016;45(1):85–96.

- Kulkarni M, Lengnick-Hall ML. Socialization of people with disabilities in the workplace. Hum Resour Manage. 2011;50(4):521–540.

- Inge K, Bogenschutz D, Erikson D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to employment: as reported by individuals with spinal cord injuries. J Rehabil. 2018;84(2):22–32.

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. Views and experiences of employment among people with psychosis: a qualitative descriptive study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005;51(4):302–316.

- Saunders S, MacEachen E, Nedelec B. Understanding and building upon effort to return to work for people with long-term disability and job loss. Work. 2015;52(1):103–114.

- Boyce M, Secker J, Johnson R, et al. Mental health service users’ experieces of returning to paid employment. Disabil Soc. 2008;23(1):77–88.

- Lexén A, Hofgren C, Bejerholm U. Reclaiming the worker role: perceptions of people with mental illness participating in IPS. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(1):54–63.

- Tschopp MK, Perkins DV, Wood H, et al. Employment considerations for individuals with psychiatric disabilities and criminal histories: consumer perspectives. J Vocat Rehabil. 2011;35(2):129–141.

- Soeker M, Truter T, van Wilgen N, et al. The experiences and perceptions of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia regarding the challenges they experience to employment and coping strategies used in the open labor market in Cape Town, South Africa. Work. 2019;62(2):221–231.

- Jakobsen K. If work doesn’t work: how to enable occupational justice. J Occup Sci. 2004;11(3):125–134.

- Lock S, Jordan L, Bryan K, et al. Work after stroke: focussing on barriers and enablers. Disab Soc. 2005;20(1):33–47.

- Eriksson UB, Engstrom LG, Starrin B, et al. Falling between two stools; how a weak co-operation between the social security and the unemployment agencies obstructs rehabilitation of unemployed sick-listed persons. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(8):569–576.

- Hielscher E, Waghorn G. Managing disclosure of personal information: an opportunity to enhance supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(4):306–313.