Abstract

Purpose

Theoretically, individualised funding schemes empower people with disability (PWD) to choose high quality support services in line with their needs and preferences. Given the importance of support, the aim of this scoping review was to understand the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability.

Methods

A comprehensive scoping review of the published literature from 2009–2019 was conducted on five databases: Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO and Scopus.

Results

Of the 3391 records retrieved, 16 qualitative articles were eligible for review. Thematic synthesis of the findings revealed six key interrelated themes: (1) choice and control, (2) individualised support, (3) disability support worker (DSW) qualities, (4) DSW competence, (5) PWD – DSW relationship, and (6) accessing consistent support. The themes depict factors influencing the quality of paid disability support from the perspective of PWD, close others and DSWs.

Conclusions

Although the evidence base is sparse, the factors identified were in line with international rights legislation and policy ideals. The findings can provide insights to PWD hiring and managing support, and facilitate the delivery of quality disability support. Further research is required to understand the interactions between the factors and how to optimise support in practice.

The quality of paid disability support is determined by a multitude of interrelated factors influenced by the disability support worker’s qualities and competencies, the interaction between the person with disability and the disability support worker, as well as external contextual factors.

Optimising choice and control for adults with acquired neurological disability and providing individualised support should be a significant focus for disability support workers.

Training modules for disability support workers can be informed by five of the identified themes: (1) choice and control, (2) individualised support, (3) DSW qualities, (4) DSW competence and (5) the relationship between PWD and DSWs.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

In the past decade, the landscape of disability support services has undergone fundamental reform with greater emphasis on personalisation and a global shift towards individualised funding schemes [Citation1–4]. The core values of individualised funding schemes reflect the rights of people with disability (PWD) to participate fully and independently in society, as outlined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [Citation5,Citation6]. Individualised funding schemes provide individuals with personal budgets to purchase support services in line with their needs and preferences [Citation7]. Theoretically, the market-based approach to individualised funding schemes place PWD at the heart of decision making [Citation8,Citation9]. However, in order to make informed decisions, adults with disability require sufficient information and a quality workforce from which to choose.

In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in mid-2013 as a national public social insurance scheme designed to provide individualised funding packages to people with “permanent and significant disability” [Citation10], as well as helping PWD to access mainstream and community services, and maintain informal supports [Citation11]. The NDIS replaces a disability system described by the Productivity Commission as “underfunded, unfair, fragmented, and inefficient”, arguing that it gave PWD “little choice and no certainty of access to appropriate supports” [Citation12]. By the end of 2019, 338,982 PWD were being supported by the scheme, including 12% of NDIS participants with an acquired neurological disability [Citation13].

Adults with acquired neurological disability (e.g. acquired brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury or neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis or Huntington’s disease, and cerebral palsy) often experience severe or profound core activity limitations, meaning quality disability support is critical to ensuring the principles of individualised funding schemes are actualised and individuals are empowered to exercise choice and control. Many adults with acquired neurological disability experience cognitive, communication and physical impairments at varying levels of severity and therefore often rely on high quality paid disability support to live an ordinary life. Given the sudden and traumatic onset of many acquired disabilities, the experience of disability for adults with acquired neurological disability and their support needs are distinct from those of adults with developmental intellectual disability [Citation14,Citation15], whose experiences reflect lifelong functional limitations. Although, in a recent review on the quality of care relationships, Scheffelaar et al. [Citation16] stated that client group-specific focus may not be necessary, quality of support for this cohort is yet to be defined sufficiently. Thus, it is reasonable to expect the quality determinants for this group to differ due to the nature of their support needs. Moreover, there is a paucity of literature around the quality of support for adults with acquired disability, and recent evidence demonstrates that people with acquired disability respond differently to support working practices designed for people with intellectual disability [Citation14]. Thus, this review will focus solely on mapping the factors that influence support for adults with acquired neurological disability.

With the full implementation of the NDIS in 2020, $22 billion will be spent on individual supports, with most of this funding being spent on disability support workers (DSWs) [Citation13]. DSWs are fundamental to quality of life and health outcomes for PWD with complex needs [Citation17,Citation18], as they provide support for a complex range of activities ranging from personal hygiene, dressing and feeding to facilitating meaningful engagements and supporting people with housing, employment and financial responsibilities [Citation19–21]. The overarching role of DSWs is to promote the independence of adults with disability and build their capacity to make decisions, participate in the community and achieve their self-described goals [Citation7,Citation22]. In this paper, the term disability support worker (DSW) will be used in a broad sense to refer to all employees who provide direct and daily support to people with disabilities.

Quality of “care” has been defined primarily in the healthcare literature, with the traditional definition limited to medical outcomes [Citation23–25]. However, there is a paucity in the literature around the quality of nonclinical support for PWD [Citation25]. Thus, this review will keep the definition of “quality of support” broad to capture all factors considered to improve or impede the effectiveness of the support provided. Fundamental to a quality framework for disability support is the lived experience and preferences of PWD. Additionally, it is important to consider the views of DSWs as the providers of support in order to identify any differences in priorities and help guide DSW training in line with the preferences of PWD. Close others are also critical for populations with complex needs as often they provide support to PWD recruiting, hiring and managing DSWs, and PWD may receive paid support in the family home. Thus, this review aims to develop themes to illustrate factors that influence the quality of support grounded in the lived experience of PWD, close others and DSWs. Given the heterogeneity of adults with acquired neurological disability and the diverse nature of activities for which DSWs provide support, there is likely to be a range of factors that influence the quality of support.

Despite the NDIS, and other individualised funding schemes internationally [Citation26], adopting a person-centred model of support with increased funding, the quality of support provided is largely determined by the workforce. The Australian Government Productivity Commission (2017) [Citation27] estimated the disability workforce at 73,600 full-time equivalent workers in 2014–15 but that by 2019–20, 162,000 full-time equivalent workers would be required to deliver person-centred support in line with the needs and preferences of the expected 460,000 NDIS participants. Concerningly, however, since the roll out of the NDIS the DSW role has had the largest increase in casualisation, the largest number of vacancies and the biggest reduction in experience levels in the disability sector [Citation28]. As well as an adequate number of DSWs, the workforce needs the skills to implement consistent, person-centred quality support [Citation29]. However, the disability support workforce is largely made up of under-skilled, non-professionals with limited qualifications [Citation30,Citation31] and the nature of individualised funding schemes allows inexperienced, unqualified individuals to present themselves directly to PWD [Citation32]. Additionally, the opportunities for formal training and performance monitoring are reduced [Citation30,Citation33,Citation34], particularly for DSWs directly employed by PWD [Citation35,Citation36], as individualised funding packages often do not sufficiently allow for training and development [Citation37–39]. Trends towards casualisation and increasingly unpredictable patterns of demand are also apparent within individualised funding schemes [Citation28,Citation30], increasing staff turnover rates and reducing job security for DSWs. Unsurprisingly, poor work conditions and low levels of organisational support have been shown to reduce the quality of support (in terms of DSW skill and experience) [Citation29,Citation31,Citation40]. Whilst, in the context of support provision for older adults, better working conditions (e.g. guaranteed working hours and more training opportunities) have been associated with higher quality support [Citation41].

Evidence suggests that cohesive relationships between DSWs and PWD can facilitate better support [Citation16,Citation42–46], however it does not always result in productive support [Citation47], and very close relationships can be detrimental to support provision [Citation48]. Within the individualised funding context, research has shown direct employment arrangements can foster a better relationship as they facilitate greater autonomy for the PWD and better communication and trust between the person with disability and the DSW [Citation49–51]. However, with limited information available for PWD regarding the determinants of quality support, direct employment allows adults with disability to place more emphasis on the relatability of DSWs e.g. similar interests and age, over their capacity to fulfil the role [Citation52]. Although, it has been suggested the quality of support is more dependent on the relationship than expert knowledge [Citation53], this is conditional to establishing and maintaining appropriate boundaries, which is complex in itself [Citation54–56]. Thus, in order to empower adults with disability to effectively exercise choice and control within individualised funding frameworks and make informed decisions when navigating support systems, it is critical to understand the mechanisms by which the relationship impacts the quality of support.

In summary, there are a number of elements that can influence the support provided to PWD, but a definition of quality disability support is yet to be established. As described, the disability workforce and the working conditions are important, as is the relationship between the person with disability and the DSW. However, there is a gap in the literature considering all the factors that may influence the quality of support, and the mechanisms by which quality is improved. As a result, there are no standardised quality indicators of quality support. Thus, in recognising the importance of support for people with acquired neurological disability, the aim of this scoping review was to examine the existing evidence base and map the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability from the perspective of people with lived experience, close others of people with lived experience and the disability workforce.

Methods

The systematic scoping review method was informed by the six-stage approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [Citation57] with the methodology modifications recommended by Levac and O’Brien [Citation58] and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation59]. The methodology is detailed in the scoping review protocol [Citation60].

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The following research question was identified for this review:

What are the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability and complex needs?

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

A systematic search strategy was developed by the authors in consultation with content experts and a research librarian (see ). Three broad search terms: disability, support and quality were searched on MEDLINE and EMBASE databases to identify keywords and further search terms. Using this initial search, prior knowledge of the topic area, and known peer-reviewed literature, a comprehensive list of search terms was developed. The initial search strategy included three concept headings: (1) acquired disability, (2) paid support, and (3) barriers and facilitators. After preliminary searches on MEDLINE, the third concept, barriers and facilitators, was removed as the search became too limited. Thus, the final search strategy combined terms within two broad concepts: (1) acquired disability and (2) paid support.

Table 1. Search strategy.

The search was conducted on Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus and Embase. Search terms were adapted for use with each bibliographic database, with MeSH and Emtree headings used where appropriate. Searches were limited to studies involving human participants published in English between January 2009 and December 2019. This timeframe was considered appropriate with evolution of the disability system in the past decade and the international trend towards individualised funding and budgets. Reference lists and forward citations of eligible studies were hand searched, and publications by the authors of included studies were identified using Scopus to screen for further relevant articles.

Stage 3: Study selection

Peer reviewed articles with extractable primary research data were included. All study designs were considered. Non-empirical studies, reviews, books/book chapters, opinion pieces, study protocols and conference proceedings were excluded. To be included, studies had to report on the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for adults aged 18–65 with disability and complex needs as the results of an acquired neurological disorder (e.g. from an acquired brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury or neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis or Huntington’s disease), or adults with cerebral palsy. Studies reporting only on informal support (e.g. from family members) were excluded. Following review of 300 titles, additional eligibility criteria were implemented. Studies focused on populations with mild disability were excluded, as were studies referring only to inpatient or palliative care, or support from healthcare or disability professionals (e.g. nurses, allied health, social workers) rather than DSWs. During full text screening, further exclusion criteria were added: 1) <30% of the research population were eligible for this review, 2) data specific to the relevant population or support type could not be distinguished, or 3) the population was not described sufficiently.

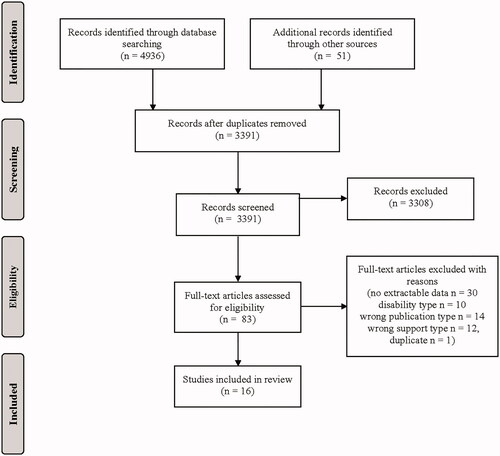

The study selection process was informed and reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [Citation38] (see ). A total of 4936 records were initially identified. Following the exclusion of duplicates, 3340 title and abstracts were screened by the first author and at least one of the other authors. Agreement was >97% between reviewers on initial screening, the conflicts were resolved by consensus. An additional 51 records were identified by the first author via hand searching, of which 10 were deemed eligible for full text screening. In total, 83 full texts were screened by two authors and 26 were deemed eligible for the next stage. Following charting the data, 16 articles were retained for review.

Stage 4: Charting the data

Data extraction was an iterative process conducted by the lead author and checked by the two coauthors. Twenty-six articles were deemed eligible following full text screening. The lead author extracted data from the 26 articles to describe the population, the support type, design and methods, and a summary of findings in relation to the research question. This process resulted in excluding 10 studies because they reported only on access to support, not in relation to quality of support (n = 4), there was no empirical data to extract (n = 2), or the population was not described sufficiently (n = 4). Additional data was extracted for the 16 included studies with respect to the research question. The final step involved splitting the studies by the perspective of the data reported (e.g. PWD, family members or informal supports, paid support workforce or studies with multiple perspectives). Additionally, where authors had identified and reported gaps in the literature and research implications, the review authors charted this also.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews was used to guide the collating, summarising and reporting of results [Citation59]. Key study characteristics of the included articles are reported in , and participant characteristics in .

Table 2. Study characteristics.

Table 3. Participant characteristics.

Following the descriptive summary, given the qualitative nature of the selected studies, Levac et al.’s [Citation58] suggestion to conduct a thematic synthesis was implemented. Familiarisation of the study findings was achieved through reading and re-reading the results of the reviewed articles and charting the data. As few studies directly addressed the review question and some studies included participants who did not fit the review population eligibility, some findings were irrelevant. To be included in the analysis, the data had to relate to the review question and the population eligible for the review. The lead author extracted the primary data (quotes from participant interviews) and the author reported findings and entered the data into NVivo software. The quotes and authors comments were labelled to reflect the perspective of the participant group e.g. PWD, close others or paid support workforce (DSWs or service providers).

The process of data synthesis followed a thematic analysis approach in line with Thomas and Harden’s [Citation78] three stage methodology. Thomas and Harden argue that this qualitative analysis method is suitable to answer review questions about “people’s perspectives and experiences”, in line with the aim of this review [Citation78]. The first stage of thematic analysis involved examining and coding the data line by line. The primary data (e.g. participant quotes) and the author reported findings were examined separately. Although only data relating to the review question had been extracted, during this initial coding the review question was not considered. Descriptive codes were created by directly extracting meaning from the quote or authors’ description of the findings. The second stage involved refining and comparing the descriptive codes across the primary data and the findings as stated by the authors of the primary studies to develop descriptive themes. Stages one and two were conducted simultaneously; as more data was coded, the codes were refined and re-categorised to better describe the body of data, and reduce duplication of codes. Consequently, the text was repeatedly examined helping to ensure consistency in the interpretation of data across different papers. The final stage involved analysing the descriptive themes in relation to the review question and advancing to a more conceptual understanding. “Factors that influence the quality of support” from the perspective of the different participant groups (e.g. PWD, close others and paid support workforce) were inferred from the descriptive themes and integrated into superordinate themes. Throughout the process memos were utilised to note the links between the factors and track the conceptualization of the findings. The memos guided the frequent discussions and reflections between the three authors during the analysis process.

Due to the data synthesis method, all of the data extracted from each of the individual sources of evidence has not been tabulated. Instead, to more effectively answer the review question, the themes identified around the factors that influence the quality of support have been presented. reports the high-level themes with participant quotes to illustrate the perspectives of the three groups. depicts which articles the data emerged from and details the themes with sub-themes that emerged from the thematic analysis.

Table 4. Participant quotes to illustrate the key themes around factors that influence the quality of support.

Table 5. Themes and sub-themes depicting the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support.

Expert consultation

The scoping review protocol [Citation60] described co-design workshops to explore “what makes an excellent support worker?” from the perspective of PWD. The intention is to conduct the workshops at a later date. However, as a first step in this process, we engaged with an expert consultant (the “expert”) for feedback on the review findings post-analysis. His expertise reflects his own lived experience of paid disability support and his experience of disability advocacy work. The expert was invited to review the thematic analysis findings and provide feedback on the results considering 4 questions: 1) what do you agree with, 2) is there anything you disagree with, or are surprised by, 3) is anything missing, and 4) what factors are most important. It was emphasised that all feedback and suggestions were encouraged, and the questions were provided as a guide.

Results

Study characteristics

The sixteen articles deemed eligible for review spanned research from Sweden (7), Australia (3), New Zealand (3), the United Kingdom (2), and Denmark (1) and were published from 2009 to 2019. All reviewed studies used qualitative methodology. Data generation techniques included direct participant interviews (n = 15), focus groups (n = 3), surveys (n = 1) and observation (n = 1). Qualitative data analysis techniques included content analysis (n = 7), thematic analysis (n = 6), and phenomenological analysis (n = 3). The focus of the studies varied but all papers reported on data relating to factors that influence the quality of paid support. The perspectives of PWD, DSWs, informal carers and family members were represented within the data. Study characteristics are provided in .

Participant characteristics

A summary of the participant characteristics is presented in . The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 12–72, with a combined total of 519 participants. It must be noted that not all participants were eligible for this review, however results were only extracted when the participant group could be identified as eligible, or the number of eligible participants in the study exceeded 30%. Ineligible participant groups have not been listed in . Additionally, 5 of the 16 papers were conducted by the same authors on the same cohort of participants [Citation61–63,Citation73,Citation74] but from multiple perspectives, further reducing the number of individual participants. Participants included PWD, DSWs, service providers, informal carers and family members. Data from service providers, although representing disability organisations rather than individual DSWs, have been grouped with DSWs for the purpose of this analysis as only two papers [Citation66,Citation71] gave the perspective of service providers. This distinction is explicit throughout the results however. Eligible disability types represented in the studies included acquired brain injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy and other neurological disorders. Participants with disability had varying support needs. Where reported, the support provided ranged from 4–24 h per day and the participants (or their close others) had been receiving or providing the support from 3–41 months prior to the study.

Factors that influence the quality of support

Six key interrelated themes emerged with 18 sub-themes that depicted the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support. The following themes were identified across the primary data and author reported findings: (1) choice and control, (2) individualised support, (3) DSW qualities, (4) DSW competence, (5) the relationship between PWD and DSW, and (6) accessing consistent support. Considerable overlap and interaction within and between the themes was evident, as is highlighted in the results. Asterisks are used throughout the results to depict when the theme or subtheme emerged only from the author reported findings in the paper, rather than primary data (e.g. illustrative quotes).

The perspective of PWD, close others and paid support were captured as reflected by the selected quotes in . depicts which studies and which participant group informed the themes and sub-themes. The unspecified column relates to findings from studies with multiple participant groups where the perspective was not identified in the results.

Choice and control

The first theme, choice and control, encapsulates the importance of the person with disability being able to (1) choose and manage their support, (2) be involved in decision making, and 3) use their own capacity. This was highlighted by all participant groups across 9 studies involving interviews investigating relationships [Citation64], needs [Citation65], quality of care [Citation67], dependence on care [Citation69], strategies to achieve autonomy [Citation73] and other life experiences [Citation35,Citation74] post-acquiring the disability, as well as the experiences of paid support for close others [Citation62] and DSWs’ work experiences [Citation63].

Choosing and managing support. The subtheme, choosing and managing support, was extracted from 6 articles from the perspective of PWD [Citation64,Citation65,Citation73,Citation74*], close others [Citation62] and DSWs [Citation63]. PWD emphasised the importance of being allowed to choose “who, and what we’re going to do together and when” [Citation73]. This subtheme was primarily concerned with being able to choose the “type of carers [they] like” rather than workers “swapping and changing” [Citation64] beyond the control of the person with disability. One participant with disability described it as a “business looking after someone with a spinal injury” and stressed the importance of the person with disability having a plan and a policy set up for employing support workers [Citation65].

PWD involved in decision making. Similar to the aforementioned sub-theme, all participant groups emphasised the importance of DSWs enabling the person with disability to participate in decisions impacting upon their life. Six studies reported findings from the perspective of PWD [Citation35,Citation65,Citation67,Citation69*,Citation73,Citation74], with one participant emphasising that “it’s about your life… it’s about what’s important to you” [Citation67]. The same participant argued that involving the client in decision-making improves the quality of support and when this doesn’t happen “there is a feeling of loss of power”, further highlighting the importance of autonomy and control over one’s life in the context of support. Family members saw it as a lack of respect when DSWs “took over” or “performed tasks without discussing how they should be done” [Citation62]. Correspondingly, DSWs in Ahlström & Wadensten’s [Citation63] study claimed that supporting the person with disability to make decisions about daily activities is part of being professional, and it is disrespectful to argue with or act against the will of the person with disability.

Chance to use own capacity. In addition to making their own decisions, PWD emphasised a desire to capitalise on their abilities, and only have support workers do the tasks that they were unable to do themselves [Citation73,Citation74]. Moreover, people with disability felt it was degrading when support workers did tasks for them that they were capable of doing themselves [Citation74]. For close others, it was the cooperation between the person with disability and the DSW that was key to ensuring the person with disability could participate in life to the extent their capacity allowed [Citation62], and they stressed that this was not possible when the support worker “takes over”. Consistently, DSWs suggested that allowing people to be more self-reliant gives them a sense of security [Citation61], and in turn more confidence to utilise their capacity.

Individualised support

Eleven studies reported findings suggesting a person-centred, individualised approach to disability support is critical. The second theme, individualised support, comprised three sub-themes: (1) person-centred approach, (2) responsiveness to needs and (3) meeting language and cultural needs. The overarching message extracted from the articles was that being seen as human, irrespective of disability, is the foundation of good quality disability support.

Person-centred approach. Results presented from the perspective of PWD [Citation35,Citation64,Citation67,Citation68,Citation75] and close others [Citation67,Citation70] suggested a preference for DSWs taking a person-centred, humanistic approach to support. Feeling “seen” as a person was described by multiple participants with disability [Citation35,Citation67,Citation75]. For example, a participant with multiple sclerosis expressed feeling understood and seen as a person when her support worker made individualised suggestions around her care [Citation67]. Being treated as a person was also associated with feeling respected [Citation35]. This type of support was referred to as a “human approach” by Fadyl et al. [Citation67], and encompassed being treated as a person, having involvement in their support, and being listened to and taken seriously. Thus, this theme is strongly linked with the choice and control theme.

Responsiveness to needs. Across eight studies, all three participant groups suggested that DSWs needed to be responsive to the individual’s needs, as opposed to applying generalised practices to support [Citation35,Citation61,Citation67–70,Citation73,Citation74]. This sub-theme is consistent with the person-centred approach sub-theme, but is specifically about understanding the needs of the individual and having the ability to be flexible in working practices to respond to those needs. As highlighted by participants in Gridley et al.’s study [Citation68], this is important for people with complex needs as it is often difficult to predict support requirements. For example, a member of a brain injury organisation said “brain injury care pathways that are linear don’t work”. Close others appreciate that it can take time for support workers to “build up that understanding” [Citation67] of the individual’s needs. However, in order to be responsive to needs the support worker must have good “perceptive awareness” of the individual’s needs and the ability to imagine how the other person is feeling [Citation61], as well as the capacity to be flexible in their working practices [Citation67,Citation68].

Meeting language and cultural needs. In line with being responsive to needs, participants with disability valued support sensitive to their specific language and cultural needs [Citation67,Citation75]. The explicit focus of Yeung et al.’s [Citation75] study was the experiences of Chinese PWD living in the UK and all participants appreciated support that met their language and cultural needs, or were Chinese-specific. This preference extended across all welfare services. Cultural appropriateness in support services was highlighted in Fadyl et al.’s [Citation67] study in relation to the Maori community in New Zealand. These findings are associated with providing a human approach to care, in that DSWs need to understand the individual’s needs and provide appropriate support.

DSW qualities

Central to the provision of quality individualised support was the personal attributes of DSWs. provides the full list of attributes referenced in the papers. Most of the desired attributes pertained to building rapport and relationships e.g. being understanding, empathetic, respectful, considerate, optimistic, friendly and trustworthy. Some were concerned with an openness to change e.g. being flexible, perceptive, creative and willing to listen. Others were more professional attributes e.g. reliability, focus and patience. A common theme throughout the papers was the importance of DSW’s having the “right attitude”, with PWD in Gridley et al.’s [Citation68] study arguing that attitude and personality of staff is more important than training. Within this theme, three qualities of a good DSW were identified to capture the essence of the “right attitude” from the most frequently mentioned attributes: (1) willingness to listen and learn, (2) empathy and understanding and (3) respect.

Table 6. List of DSW qualities referenced in reviewed papers.

Willingness to listen and learn. A key contributor to quality support was the DSW’s willingness to be open, learn and take direction, linking to the importance of choice and control for the person with disability. This quality was illustrated by findings from the perspective of PWD [Citation35,Citation67–69,Citation74] and close others [Citation67]. The findings suggest that in order to be responsive to needs and provide individualised support, DSWs need to be willing to listen and learn [Citation65,Citation67,Citation69,Citation74], and follow instructions [Citation69] from the person with disability or their close others.

Empathy and understanding. Another essential quality in a DSW referenced by PWD [Citation35,Citation65,Citation67,Citation74], close others [Citation62,Citation70] and DSWs [Citation61,Citation63] was the ability to be empathetic and understand the needs of the individual they are supporting. Findings reported from the perspective of DSWs stressed the need to “adopt another person’s perspective” [Citation63] and “feel the other person’s feelings” [Citation61] in order to best support the individual. Empathy and understanding in a support worker fosters a more beneficial relationship [Citation35,Citation61,Citation62], enables the support worker to be more responsive to needs [Citation61,Citation63,Citation67,Citation74] and the person with disability to feel more empowered to use their own capacity [Citation62,Citation74].

Respect. In order to provide quality support, DSWs must show the person with disability respect. Respect was valued by PWD [Citation35,Citation68,Citation74], close others [Citation62] and also recognised as important by DSWs [Citation61,Citation63]. Showing respect involved allowing the person with disability to exercise choice and control by making their own decisions and using their capacity [Citation62,Citation63], seeing the person as an individual [Citation35] and demonstrating a thorough understanding of their situation [Citation74]. Close others felt support workers were lacking in respect when they treated their relative paternalistically [Citation62] and disregarded their opinions. Conversely, findings from Wadensten & Ahlström [Citation74] suggested that when the person with disability felt respected, their self-confidence increased, and in turn they felt more able to use their own capacity.

DSW competence

Across 12 studies, participants described the DSW competence as a key factor influencing the quality of support. This factor was illustrated by references to (1) knowledge, training and experience and (2) practical skills.

Knowledge, training and experience. PWD [Citation65,Citation67], close others [Citation67] and DSWs [Citation63] spoke of the importance of DSWs being effectively trained and having sufficient knowledge about the disability and most importantly, the individual. The data presented around knowledge was mostly framed negatively, with PWD [Citation65,Citation67] and DSWs [Citation63] arguing that DSWs did not have sufficient knowledge or experience. Accordingly, the need for effective training and education was also referred to [Citation63,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation70], with DSWs [Citation63] and service providers [Citation66] expressing that DSWs did not receive sufficient training to perform their role. Further, Mitsch et al.’s [Citation71] findings imply that the location of the person with disability’s residence can exacerbate the level of inequity in services, as there is a lack of workers with the speciality training, knowledge and skills required to work with people with acquired brain injury in rural and remote areas.

Practical skills. PWD expressed that in order to meet their needs, DSWs need to have practical skills [Citation35,Citation65,Citation69]. In Martinsen & Dreyer’s [Citation69] study, participants articulated that “a lack of practical skills… could restrict the dependent person’s experience of freedom”. In line with the DSW’s practical skills, DSWs [Citation63,Citation72] emphasised the importance of assistive devices in providing quality support. Close others, when discussing the role of DSWs to enable “freedom of movement” for their relatives, suggested a lack of assistive devices can result in limitations of freedom [Citation62]. Thus, it appears the DSW’s ability to effectively use assistive devices is important in providing quality support.

Relationship

Twelve studies reported dimensions of the relationship between the person with disability and the DSW that either enabled or constrained the quality of support provided. The sub-themes (1) personal chemistry, (2) knowing the individual and (3) trust capture factors that enable a positive relationship and in turn, better quality support. The dilemma of (4) boundaries and friendship in this close working relationship was highlighted in reference to protecting the person with disability’s privacy, whilst still maintaining a trusting relationship. Accordingly, friendship between the person with disability and their support workers was discussed as both a facilitating and restricting factor when providing support.

Insights into what facilitates a good relationship between the person with disability and the DSW were also extracted from the data. PWD said that being open and flexible with DSWs [Citation73] fosters a good relationship, and that DSWs need to have strong communication skills and show engagement with an open mind for the needs of the person with disability [Citation35]. DSWs highlighted the importance of receiving positive feedback from the person with disability [Citation63], and close others recognised mutual respect between the DSW and the person with disability as key to the relationship [Citation62].

Personal chemistry. Central to forming a good relationship was the personal chemistry between the person with disability and their DSW. Across six studies, PWD [Citation68,Citation69,Citation74], close others [Citation62] and DSWs [Citation61,Citation63] highlighted the importance of personal chemistry for the support relationship. Expressed in identical terms in Wadensten & Ahlström’s papers [Citation61–63,Citation74], personal chemistry encompasses having shared interests [Citation61,Citation63,Citation68,Citation69,Citation74], generally “getting on” [Citation61,Citation62,Citation68] and being able to relate to one another [Citation68].

Knowing the individual. From the ideas expressed by PWD [Citation35,Citation64,Citation67–69,Citation73] and close others [Citation62,Citation67], knowing the individual was inferred as a critical factor in providing quality support. Consistent with the individualised support theme described above, findings reported from the perspective of PWD and close others indicated that familiarity reduces the burden of repeatedly instructing their support worker and enables the DSW to be responsive to their needs [Citation64,Citation67–69]. Additionally, from the perspective of family members, the person with disability knowing their support worker well provided a feeling of security [Citation62]. PWD [Citation35,Citation64,Citation68,Citation69] and close others [Citation62,Citation67] appreciated that it takes time to get to know the individual and build the relationship, hence continuity in support (discussed further in the final key theme) was highlighted as critical in relation to knowing the individual.

Trust. Trust was reported as a key contributor to a good relationship between the DSW and the person with disability, as reflected in findings from each of the three participant groups. PWD [Citation73,Citation74] referred to trusting their DSW with private matters e.g. “What I tell them stays with them; it doesn’t get passed around. And it’s good if you can have trust in that way…” [Citation74] and trusting them not to “talk rubbish” [Citation73]. This trust built over time and came from knowing the individual well [Citation68,Citation73,Citation74]. Informal supports (close others) [Citation70] also identified being trustworthy as a “core component” of quality support. However, in order to create a trusting relationship, findings from the paid support perspective imply that the balance between boundaries and friendship is critical [Citation61].

Boundaries and friendship. While the importance of a close relationship was evident across most reviewed studies, setting boundaries in the relationship was also stressed by PWD [Citation64,Citation65,Citation68,Citation73,Citation74] and DSWs [Citation61,Citation63]. Boundaries were characterised in the author reported findings and participant quotes by “distance”, the extent of “personal closeness”, and “friendship” [Citation61,Citation63,Citation68,Citation73,Citation74]. The nature of the boundaries deemed necessary varied by participant and across the different perspectives. Whilst some participants with disability [Citation35,Citation65,Citation68] and close others [Citation62] preferred friendship-like relationships, others expressed a preference for business-like relationships [Citation65,Citation68], further highlighting the importance of individualised support. Accordingly, DSWs highlighted the dilemma they face in setting boundaries and distinguishing the working relationship from personal friendship [Citation61,Citation63].

Two studies referred to the impact of a lack of boundaries on support work. One DSW [Citation61] suggested that crossing boundaries can lead to “an implicit demand to work overtime”. However, another DSW in the same study [Citation61] said that being “totally open” can be positive as “you can almost feel the other person’s feelings”. Correspondingly, in the work of Braaf et al. [Citation65], a participant with disability expressed that for him, “it works” to be close to his support worker as they become “permanently part of your life”. Thus, balancing the professional and the personal in the relationship according to individual preferences appears fundamental to quality support.

Boundaries were also discussed in other contexts, for example PWD talked about boundaries in reference to protecting their “private sphere”, as it can be difficult for people who require high levels of support to maintain a private life [Citation73,Citation74]. Additionally, Wadensten and Ahlstom spoke of setting boundaries on the support worker’s tasks so the person with disability still has a chance to use their own capacity [Citation73].

Accessing consistent support

The final theme, accessing consistent support, was identified as an essential precursor to quality support within 12 of the reviewed papers. This theme incorpates 3 subthemes: (1) continuity of support, (2) funding and (3) availability of support.

Continuity of support. Underpinning many of the factors determining the quality of support was continuity of support. This subtheme pertained to factors within the individualised support and relationship themes. Continuity of support was noted as important by PWD, close others and DSWs for developing familiarity [Citation35,Citation64,Citation68,Citation69,Citation75], building trusting relationships and setting boundaries [Citation62,Citation64,Citation68,Citation74]. A lack of continuity of support was reported to cause stress and anxiety for PWD [Citation65,Citation68,Citation73,Citation74] and their close others [Citation62,Citation68] due to associated difficulties with recruiting new support workers and rebuilding the relationship. When discussing the difficulties with recruiting new support workers, PWD in Wadensten and Ahlström’s [Citation73] study emphasised the importance of being tolerant and flexible to make the new support relationship work. Further, the issue of inconsistent support was exacerbated in rural and remote locations due to high staff turnover [Citation71]. This issue is further discussed in the availability of support subtheme.

Funding. Continuity of quality support could not be achieved without sufficient funding, as highlighted by PWD [Citation35,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68], close others [Citation68] and service providers [Citation66]. Both PWD [Citation65] and service providers [Citation66] reported that compensable participants were more likely to access adequate support. A lack of sufficient funding caused PWD anxiety about future support needs [Citation35,Citation65], especially those who were non-compensable and reliant on fluctuating local authority budgets [Citation66]. PWD also highlighted that funding can determine the amount and type of support they can access, which does not always match their own priorities [Citation64]. In line with this, personal budgets and direct payments were considered critical for achieving personalised support by participants in Gridley et al.’s [Citation68] study. The impact of limited funding on the ability of service providers to engage support staff with specialised skills [Citation66] was also highlighted as resulting in less availability of quality support for PWD.

Availability of support. Availability of support, as previously mentioned, was impacted by funding for service providers [Citation66] and by geographical location [Citation64,Citation71]. Mitsch et al. [Citation71] investigated the brain injury rehabilitation services for people living in rural and remote areas in Australia from the perspective of service providers, service users and family members. The findings revealed that fewer specialised ABI support services were available for those living in more remote and rural areas. This problem was due to difficulties recruiting staff with the knowledge and skill required to work with people with complex needs. Correspondingly, a participant with disability in Braaf et al.’s [Citation65] study highlighted the difficulty she had in “finding an extra carer” because of where she lived. Recruitment issues were also noted by close others from a county in central Sweden [Citation62] suggesting this problem is not exclusive to rural and remote areas.

Expert consultation

The overarching message from the expert’s review of the findings was that all of the themes were important, and in his opinion, the review presents an accurate reflection of the disability support work experience for PWD. Critically, the expert stressed the key to quality support was the person with disability having choice and control, and the DSW seeing their client as a person first. The expert explained that “duty of care” within support work can undermine choice and control, as it can be interpreted as the responsibility of the DSW to ensure their client is safe according to their own opinion, as opposed to the person’s wishes. The expert also discussed the relationship theme and agreed that it is difficult to achieve the balance between the professional and social relationship. In his experience, vigiliance, openness and honesty on both sides are essential to maintaining a successful relationship.

The expert also described factors not directly captured in the review. He considered accountability of the DSW as an important aspect in ensuring best practice and quality service provision. This implies the need for an external mechanism to hold DSWs accountable, pointing to the wider system in which the DSW role lies. Further, with regards to the competency theme, the expert said that with student placements, the person with disability is typically not recognised as a trainer. Instead the student’s supervisor is often viewed as the expert which can result in the person with disability having less choice and control over their support, because the student places more importance on the instructions and opinion of the supervisor. Similarly, the expert explained that PWD are not respected as credible referees for DSWs by agencies or government in Australia. This recognition is critical with direct employment arrangements, and as the expert highlighted, the person with disability is often best placed to assess the value, ability, attitude and professional standards of the DSW. Finally, he pointed out how in the context of hiring DSWs via a service provider or agency, agency policy and in turn the support provided by the DSW can be influenced by the ideology of the organisation. For example, if the agency is faith based, prohibitory policies can impact the choice and control of the person with disability, especially regarding sexuality support. These points highlight the broader systemic context that the client-DSW relationship operates within, indicating there are more players (e.g. supervisors, agencies, government) influencing the relational space than the literature has identified.

Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to explore literature reporting on factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for people with acquired neurological disability and complex needs. In undertaking this review, we identified that little research had been conducted to directly investigate this topic. Despite the paucity of literature, we identified 16 studies with varying aims that shed light on the issue. All 16 studies used qualitative methodology and reported relevant data that could be extracted and analysed. While some of these factors have appeared in previous studies exploring the experience of paid disability support, the thematic synthesis of this data provides insights into the features of paid disability support that are valued by people with acquired neurological disability, close others and DSWs. The identified factors were (1) choice and control, (2) individualised support, (3) DSW qualities, (4) DSW competence, (5) the relationship between PWD and DSW, and (6) accessing consistent support. Although a comprehensive model of the quality of support cannot be inferred from the findings of the scoping review alone, the themes that emerged offer insights into the multifactorial nature of quality support as discussed below.

Individual needs and preferences, as well as the right to choose and have control over one’s own life, are the foundation of internationally endorsed principles on the rights of PWD [Citation5,Citation6,Citation80], and the core values of personalised budget schemes [Citation1,Citation2,Citation79], including Australia’s newly introduced NDIS [Citation11]. The findings of the scoping review revealed two themes consistent with these policies: (1) choice and control and (2) individualised support, both of which were highly endorsed by the person with lived expertise who reviewed the findings. The features of choice and control valued by PWD, close others and DSWs in the reviewed studies mirror the principles of individualised funding, which in theory enable people to exercise choice and control over their supports [Citation4,Citation36,Citation81]. In line with the person-centred themes identified in the reviewed studies, there is evidence to suggest the shift towards individualised funding has necessitated a more person-centred focus in support work [Citation29,Citation38,Citation82–84], requiring support workers to be responsive to the needs of the individual [Citation39].

Quality support relies on a high quality workforce, yet traditionally the DSW role has little or no training or qualification requirements [Citation12,Citation21,Citation31,Citation32,Citation85]; indeed in practice requisite competencies and qualities are largely defined by job descriptions authored by service providers [Citation86]. Further, new individualised funding models enable people to directly hire DSWs who they consider suitable to their needs and preferences, but with that comes the employment responsibilities as well as the task of recruiting, hiring and managing the performance of DSWs [Citation50,Citation87]. Thus, it is critical to understand the qualities PWD value in DSWs but the evidence is limited, particularly within acquired disability research. In line with intellectual disability literature [Citation88,Citation89] and findings from research investigating the impact of personalisation in the disability sector in the UK [Citation50,Citation83], two reviewed articles indicated the DSWs personality or attitude can be more important than prior training [Citation68] or competencies [Citation67]. Numerous personal attributes were highly valued in DSWs (e.g. relationship building traits, being open to change), but “having the right attitude” was the overarching sentiment. However, there is uncertainty in the literature about whether “soft skills” can be effectively trained [Citation38]. Thus, it is important to define the desired personal characteristics of DSWs in order to attract the appropriate workforce and reduce high staff turnover [Citation12].

Knowledge, training, experience and skill-set were identified as key features of quality support in 12 of the reviewed studies. Although unsurprising, these factors are critical to mention given the ongoing concerns around the competencies of the disability workforce and the risk of quality control and limited opportunities for training with the shift to individualised funding models [Citation36,Citation38,Citation85]. Evidence suggests that the skills required by DSWs have expanded, in that they need to be more multi-faceted with knowledge across health, housing, leisure and employment, as well as having stronger communication skills to support people to exert choice and control [Citation50,Citation83,Citation85,Citation91]. Although empirical evidence on the impact of the NDIS in Australia is limited thus far, a recent study by Moskos and Isherwood [Citation38] showed that with the introduction of the NDIS, DSWs need to be highly skilled and flexible, with the ability to tailor supports and be responsive to needs in order to provide person-centred support. This finding is in line with the preferences expressed in the reviewed articles, although no articles explicitly pointed to the broader range of knowledge required within individualised funding schemes. Training modules could be informed by the findings from this review in corroboration of the findings arising from the aforementioned research. However, there are challenges to the provision of disability training due to funding constraints within individualised models [Citation28,Citation38], and uncertainty about where the responsibility of training lies (e.g. with the client, the DSW, service provider or the online platform by which the people access DSWs) [Citation50]. Additionally, there is a need for research designed to better understand whether the DSW attributes and competencies valued by PWD, close others and DSWs predict better outcomes for PWD, and which of these can be learned and which may be inherent within an individual.

Despite the importance of the DSW-client relationship on the quality of support, as highlighted by 12 of the reviewed studies and a recent review of long-term care relationships [Citation16], there has been limited primary research focused on the support relationship for adults with acquired neurological disability [Citation42–45,Citation47,Citation48]. There is literature on the patient-professional relationship [Citation98,Citation90,Citation93,Citation97], but the DSW-client relationship is distinct as it is often a relationship that builds over an extended time period, and can be critical to the person exercising choice and control every day. Early research [Citation47] depicted the diversity of support relationships in that they can be business-like, friendship-like or more paternal, and the nature of the relationship can determine if the working relationship is productive. Establishing boundaries is widely accepted as fundamental to facilitate the working relationship in support settings, and is often a focus of organisational policies [Citation7]. However, this review demonstrates that while some people prefer more stringent boundaries, others prefer closer more personal relationships. Accordingly, the expert consulted recognised the difficulty in striking the balance. These findings further pertain to the notion of individualised support and the importance of the DSW knowing the individual and their preferences.

Central to the success of the support relationship is the mutuality between the person with disability and their support worker. Personal chemistry, knowing the individual and trust were identified as key facilitators of a quality support relationship. Consistent with the findings of this review, recent research on broader populations who require long-term support [Citation16,Citation95,Citation96] and our expert consultation, suggests that the quality of the relationship is determined by the professional’s attitude and openness, the client’s openness and flexibility, and also the DSW-client interaction e.g. having time to get to know one another and build trust, and having mutual respect. Additionally, as highlighted by our expert consultant, it is important to consider the position of the DSW-client relationship within the wider systemic context with organisational, government and local policies, as well as other individuals (e.g. supervisors, family members) playing a role. Thus, future research considering the broader relational context is required to understand how to optimise the support relationship.

Without access to an adequate level of consistent supports, the aforementioned themes are redundant, thus the theme accessing consistent support was identified as a precursor to quality support. As evidenced in the findings of 12 of the reviewed papers, accessing consistent supports can be a challenge for PWD, despite it being necessary in order for people to exercise their rights of choice and control [Citation5,Citation10]. A preference for continuity of support was described by all three participant groups, as it enables better quality relationships and more individualised support. It also reduces the burden of recruiting and directing new DSWs for the person with disability, which has been shown to deter individuals from pursuing the option of direct employment [Citation87,Citation97]. However, the factors that are considered important to experiencing continuity of support have been shown to be variable between stakeholders, with clients putting more emphasis on service delivery and service providers focusing on the management and coordination of support [Citation98], thus there is a need for up-to-date research to understand this concept fully. Further, findings from this review stressed availability of support and funding as key to accessing support, corresponding with evidence from access to healthcare and therapy services literature [Citation99,Citation100]. It has been argued that individualised funding has improved the availability of qualified DSW in Australia, but this is dependent on remuneration and support from service providers [Citation36]. Lower pay has been shown to lead to difficulty recruiting and retaining DSWs [Citation29,Citation30], thus the impact of remuneration on quality of support requires further investigation as this could potentially disadvantage individuals in lower socio-economic groups or those with smaller funding packages who do not have the means to pay DSWs at higher rates.

Theoretically, individualised funding models enable choice and control, but there is recent evidence demonstrating self-managed funding arrangements can compound inequities between people with different types of disabilities and socio-demographic backgrounds [Citation101,Citation102]. Due to the lack of specialist disability services in rural and remote communities, this review provides evidence that geographical location can limit access to support for PWD, in line with previous research [103], as well as concerns raised by the Productivity Commission [Citation12] in Australia with the introduction of the NDIS. Further to this, previous research has shown that people with neurological impairments, mental health problems, complex needs, with limited support to manage the aforementioned increase in administrative and financial obligations, can be disadvantaged in accessing adequate funding and supports [Citation87,Citation97,Citation102]. Additionally, Mavromaras et al.’s [Citation28] evaluation of the NDIS found that people with “intellectual disability and/or complex needs; from CALD [culturally and linguistically diverse background] communities; those experiencing mental health, substance abuse, or forensic issues; and older carers who were socially isolated and had their own health issues” were less likely to receive adequate supports than others with similar needs. It is likely this is at least in part, due to the complexity of the additional administration burden in individualised funding schemes, meaning individuals with better insights or support to navigate the system may derive better outcomes [Citation102]. In terms of funding, findings from the current review revealed compensable participants were more likely to receive adequate supports. However, it is important to note the studies were conducted across varying funding schemes, and some in Australia were prior to the NDIS. Additionally, it was also stressed that individualised funding schemes are essential for achieving personalised support. Reviewing the current evidence in line with previous research, it appears that people’s circumstances can enable or constrain their access to supports [Citation101,Citation102] thus, within Australia and internationally, inequities within the population of PWD must be considered when contemplating the factors that influence the quality of support.

Limitations

Though this review offers new knowledge and understanding about the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support, the evidence base does not sufficiently inform the development of a model of quality disability support. All of the reviewed papers presented relevant data but only three of the identified studies aimed to understand the determinants of the quality of disability support explicitly. Additionally, six of the studies included broader populations than the population of interest meaning some of the extracted data could be in reference to another population with distinct support needs. Potential for overgeneralisation of the results from other disability types was minimised by only extracting data from studies where >30% of the population were eligible or when the data or author reported finding referenced the eligible population. This lack of specificity within the literature highlights the need for research directly asking people with acquired neurological disability about the factors that influence the quality of paid support. In line with the overgeneralisation concern, the reviewed set of studies included five studies by the same authors [Citation61–63,Citation73,Citation74] on seemingly the same cohort of participants with disability but from multiple perspectives, impacting the generalisability of the concepts identified across these papers. Some articles were excluded because it was difficult to establish the type of support (paid or unpaid) the authors were referring to with terms such as “carer”, thus additional data could be available that this review did not capture. Finally, as the focus of this review was to explore the breadth of the available evidence around quality of support, a critical appraisal was not conducted, meaning the weighting of the results, and therefore the importance of the factors that influence the quality of support, cannot be determined from this review.

Implications and future directions

Drawing upon the findings of this scoping review, it appears the quality of support is determined by a complex mix of interrelated factors, with choice and control emerging as the key determinants. The factors identified are consistent with internationally endorsed values on the rights of PWD, policy ideals and individualised funding principles, and were highly validated by an expert with lived experience. Further research is required to better understand how to make the human rights legislation, funding principles and policies a day to day reality for PWD and close others. In particular, focus on the real-world constraints preventing the realisation of individualised funding principles in practice is needed. Due to the heterogeneity of the factors, to improve the quality of support for people with acquired neurological disability, it is critical for PWD, DSWs and service providers to understand the determinants of quality support, as each have a part to play. Although there is a paucity of information around the weighting of the factors and how they intersect, the findings of this review can inform training for DSWs and provide input to quality improvement initiatives for disability support work. This review can also facilitate the work of DSWs and service providers by providing guidance to improve their working practices, and in turn their overall performance. Accordingly, providing evidence-based insights to PWD can empower individuals to make more informed decisions when choosing and managing DSWs, and monitoring the quality of support. The aforementioned co-design workshops will be important in complementing the review findings, to further inform the development of resources and training in order to ensure PWD receive high quality support.

Future research will serve to clarify important questions that have emerged from this review, specifically (1) how does individualised funding impact the provision and receipt of support and support relationships, (2) what other systemic factors have not been captured in this review, (3) how do the factors interact with one another, (4) are these factors of significant relevance to the acquired disability population, or more broadly, (5) do the specified DSW attributes and competencies predict better outcomes for PWD, and (6) how do real-world constraints (e.g. the aforementioned disability workforce issues) act as barriers to realising the factors identified in this review. With this evidence base, it is hoped the priorities for quality improvement will be better understood, and in turn accelerate the improvement of paid disability support for PWD.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Mr Jonathan Bredin, our expert consultant with lived experience of disability, who provided valuable insights interpreting the results of the review. We also gratefully acknowledge Dr Sue Gilbert, Senior Research Advisor at La Trobe University, for her assistance with the search strategy and review protocol.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Da Roit B, Le Bihan B. Similar and yet so different: cash-for-care in six European countries' long-term care policies. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):286–309.

- Green J, Mears J. The implementation of the NDIS: who wins, who loses? CCS J. 2014;6(2):25–39.

- Ungerson C, Yeandle S. Cash for care in developed welfare states. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave McMillan; 2007.

- Purcal C, Fisher KR, Jones A. Supported accommodation evaluation framework summary report. Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia; 2014.

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106; 2007 [cited Apr 2020]. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.htm

- UN General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Theme: Access to Rights-Based Support for Persons with Disabilities), A/HRC/34/58; 2016 [cited Apr 2020]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Disability/SRDisabilities/Pages/Reports.aspx

- Lord J, Hutchison P. Individualised support and funding: building blocks for capacity building and inclusion. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(1):71–86.

- Fisher KR, Gendera S, Graham A, et al. Disability and support relationships: what role does policy play? Aust J Publ Admin. 2019;78(1):37–55.

- Slasberg C, Beresford P, Schofield P. Further lessons from the continuing failure of the national strategy to deliver personal budgets and personalization. Res Policy Planning. 2014;31(1):43–53.

- Cukalevski E. Supporting choice and control – an analysis of the approach taken to legal capacity in Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Laws. 2019;8(2):8–19.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. Canberra: Parliament of Australian; 2013.

- Productivity Commission. Disability care and support, productivity commission inquiry: report overview and recommendations. Canberra: Australian Government; 2011.

- National Disability Insurance Agency. COAG Disability Report Council Quarterly Report. Canberra: National Disability Insurance Agency; 2019.

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Bould E. Developing and maintaining person centred active support: a demonstration project in supported accommodation for people with neurotrauma. Melbourne: La Trobe University; 2018.

- Bogart KR. The role of disability self-concept in adaptation to congenital or acquired disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(1):107–115.

- Scheffelaar A, Hendriks M, Bos N, et al. Determinants of the quality of care relationships in long-term care – a participatory study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–14.

- Bigby C, Beadle-Brown J. Improving quality of life outcomes in supported accommodation for people with intellectual disability: what makes a difference? J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31(2):e182–e200.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. 2011 [cited Aug 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-disability

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s welfare 2017 – full report. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. (13, AUS 214).

- Iacono T. Addressing increasing demands on Australian disability support workers. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35(4):290–295.

- Hewitt A, Larson S. The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: issues, implications, and promising practices. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):178–187.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. NDIS quality and safeguarding framework. Canberra: Australian Government; 2016.

- Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Shekelle PG. Defining and measuring quality of care: a perspective from US researchers. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12(4):281–295.

- Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326(7393):816–819. e1

- Lawthers AG, Pransky GS, Peterson LE, et al. Rethinking quality in the context of persons with disability. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(4):287–299.

- Laragy C. Snapshot of flexible funding outcomes in four countries. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18(2):129–138.

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Costs: Productivity Commission Study Report. Canberra: Australian Government; 2017.

- Mavromaras K, Moskos M, Mahuteau S, et al. Evaluation of the NDIS. Final report. Adelaide: National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University; 2018.

- Cortis N, Meagher G, Chan S, et al. Building an industry of choice: service quality, workforce capacity and consumer-centred funding in disability care. Final Report for United Voice, Australian Services Union, and Health and Community Services Union. Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2013.

- Alcorso C. Australian disability workforce report. 3rd edition July. Sydney: National Disability Services; 2018.

- Martin B, Healy J. Who works in community services? Adelaide: National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University; 2010.

- Jorgensen D, Parsons M, Reid MG, et al. The providers' profile of the disability support workforce in New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(4):396–405.

- Lawn S, Westwood T, Jordans S, et al. Support workers can develop the skills to work with complexity in community aged care: an Australian study of training provided across aged care community services. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2017;38(4):453–470.

- Macdonald F, Charlesworth S. Cash for care under the NDIS: shaping care workers’ working conditions? J Ind Relat. 2016;58(5):627–646.

- Nilsson C, Lindberg B, Skär L, et al. Meanings of balance for people with long-term illnesses. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(11):563–567.

- Fisher K, Edwards R, Gleeson R, et al. Effectiveness of individual funding approaches for disability support, report to the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs; 2011.

- Cortis N, Macdonald F, Davidson B, et al. Reasonable, necessary and valued: pricing disability services for quality support and decent jobs (SPRC Report 10/17). Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2017.

- Moskos M, Isherwood L. Individualised funding and its implications for the skills and competencies required by DSWs in Australia. Labour Industry. 2019;29(1):34–51.

- Ryan R, Stanford J. A portable training entitlement system for the disability support services sector. Canberra: Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute; 2018.

- Fattore T, Evesson J, Moensted M, et al. An examination of workforce capacity issues in the disability services workforce: increasing workforce capacity. Sydney: Community Services and Health Industry Skills; 2010.

- Netten A, Jones K, Ma SS. Provider and care workforce influences on quality of home-care services in England. J Aging Soc Policy. 2007;19(3):81–97.

- Miller EL, Opie ND. Severely disabled adults and personal care attendants: a pilot study. Rehabil Nurs. 1987;12(4):185–187.

- McCluskey A. Paid attendant carers hold important and unexpected roles which contribute to the lives of people with brain injury. Brain Inj. 2000;14(11):943–957.

- Meyer M, Donelly M, Weerakoon P. They’re taking the place of my hands”: perspectives of people using personal care. Disabil Soc. 2007;22(6):595–608.

- Matsuda SJ, Clark MJ, Schopp LH, et al. Barriers and satisfaction associated with personal assistance services: results of consumer and personal assistant focus groups. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2005;25(2):66–75.

- Redhead R. Supporting adults with an acquired brain injury in the community – a case for specialist training for support workers. Social Care Neurodisabil. 2010;1(3):13–20.

- Opie ND, Miller ET. Attribution for successful relationships between severely disabled adults and personal care attendants. Rehabil Nurs. 1989;14(4):196–199.

- Yamaki CK, Yamazaki Y. Instruments’, “employees”, “companions”, “social assets”: understanding relationships between persons with disabilities and their assistants in Japan. Disabil Soc. 2004;19(1):31–46.

- Leece J, Peace S. Developing new understandings of independence and autonomy in the personalised relationship. Br J Soc Work. 2010;40(6):1847–1865.

- Adams L, Godwin L. Employment aspects and workforce implications of direct payments. London: IFF Research Limited; 2008.

- Glendinning C, Halliwell S, Jacobs S, et al. New kinds of care, new kinds of relationships: how purchasing services affects relationships in giving and receiving personal assistance. Health Soc Care Commun. 2000;8(3):201–211.

- Harry L, MacDonald L, McLuckie A, et al. Long-term experiences in cash and counseling for young adults with intellectual disabilities: familial programme representative descriptions. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2017;30(4):573–583.

- Bondi L. On the relational dynamics of caring: a psychotherapeutic approach to emotional and power dimensions of women’s care work. Gend Place Cult. 2008;15(3):249–265.

- Matthias RE, Benjamin AE. Paying friends, family members, or strangers to be home-based personal assistants: how satisfied are consumers? J Disabil Policy Stud. 2008;18(4):205–218.

- Allen SM, Ciambrone D. Community care for people with disability: blurring boundaries between formal and informal caregivers. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(2):207–226.

- Browne J, Russell S. My home, your workplace: people with physical disability negotiate their sexual health without crossing professional boundaries. Disabil Soc. 2005;20(4):375–388.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. Understanding the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability and complex needs: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e034654.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.