Abstract

Purpose

Communication between patients and clinicians influences the development of therapeutic relationships. Communication is disrupted when the patient has communication impairments after stroke. However, how these communication disruptions influence therapeutic relationships is not well-understood. This qualitative metasynthesis explores the perspectives of people with communication impairment to understand how interpersonal communication influences therapeutic relationships.

Material and methods

Four databases were searched for qualitative studies which discussed how communication influenced therapeutic relationships from the perspectives of people with aphasia, dysarthria or apraxia of speech. Additional papers were identified through citation searching and subject experts. Nineteen eligible papers were included and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Four themes were constructed from the analysis: (1) Relationships provide the foundation for rehabilitation; (2) Different relational possibilities arise from “reading” the clinician; (3) Creating therapeutic relationships through validating interactions and connections; and (4) Creating therapeutic disconnections through invalidating, exclusionary interactions.

Conclusions

A therapeutic relationship develops, at least in part, in response to the clinician’s communication and how this is received and experienced by the patient. Understanding the characteristics of relationship-fostering communication and knowing how communication influences relationships can help clinicians critically reflect on their communication and better develop therapeutic relationships with people with communication impairment.

Practitioner-patient communication can facilitate therapeutic relationships or create therapeutic disconnections.

Communication patterns that are commonly evident when a patient has communication impairments can impede therapeutic relationships.

Clinicians need to attend to how their communication is received and how it influences people’s sense of self.

Communication partner training should address the existential and relational needs of people with communication impairment after stroke.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Therapeutic relationships are integral in stroke rehabilitation. These impact on patient engagement and satisfaction, and there is increasing evidence that they positively impact on rehabilitation outcomes [Citation1–3], possibly having a potentiating effect on the therapy provided [Citation1]. Because of this, there is an increasing call to attend to these relationships in research and practice and view them as an integral component in the rehabilitation process [Citation2,Citation4]. Indeed, some have called for relationship-centred care to be a model of care for rehabilitation [Citation5]. Understandings of what constitutes a therapeutic relationship differs across the literature. Bordin [Citation6], whose work in psychotherapy is influential across disciplines, proposes that the therapeutic relationship (or alliance) is comprised of the interpersonal bond between the therapist and client, and the level of agreement about the goals and activities of therapy. This definition has been critiqued in neurorehabilitation, with some arguing it is not directly applicable to the stroke rehabilitation context [Citation7,Citation8]. In this context, therapeutic relationships are said to be facilitated through interpersonal connections, a sense of collaboration, technical or professional expertise, and the patient feeling heard and valued [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. Regardless of which definition one chooses to define a therapeutic relationship, it is clear that the interpersonal relationship between a clinician and a patient is consistently recognised as a core component of the therapeutic relationship, and the interaction between them is critical to the formation of this relationship.

For those with communication impairments after stroke, therapeutic relationships can be critical for engagement [Citation5,Citation11,Citation12]. Over 50% of people experience communication impairments after stroke [Citation13,Citation14]. These impairments affect people’s ability to produce speech and expressive language, and to comprehend language. Notably, the presence of communication impairment impacts on how clinicians interact with patients [Citation15]. For instance, one study demonstrated that clinicians spent less time interacting with people with communication impairment [Citation16]. Additionally, these interactions were asymmetric, controlled by the clinician, and commonly focused on the execution of specific clinician-centred tasks such as medications or ward routines [Citation16,Citation17]. Such clinician-centred communication can leave little space for an interpersonal relationship to develop, or for a patient to feel heard or valued, potentially impacting on how, and indeed if the therapeutic relationship develops. People living with communication impairment have highlighted the importance of communication in building a therapeutic relationship with the clinician [Citation11,Citation18]. Bright and colleagues [Citation11] proposed “relational communication” as a construct, a multidimensional approach to communication and interaction which fostered therapeutic relationships and engagement. This involved authentic dialogue, clinical and non-clinical content, a range of verbal and non-verbal communication acts, and supported communication techniques, i.e., modifying communication so that people could fully participate. Supported communication techniques are designed to help communication partners interact in ways that acknowledge the person’s competence and support the person to understand and express themselves [Citation19]. While these approaches recognise that communication is integral to establishing and maintaining relationships [Citation20], the ways in which clinicians enact these approaches can see them emphasise the use of communication techniques and behaviours [Citation11,Citation20]. This can lead to a transactional approach which does not support the development of a therapeutic relationship [Citation11]. If we are to enhance therapeutic relationships and try and ensure these relationships have the full therapeutic effect possible [Citation1], then enhancing relationship-fostering communication may be critical. However, to do this, we need to better understand: (1) the interplay between communication and therapeutic relationships and in particular, how communication might produce particular relational possibilities; and (2) the core characteristics of relationship-fostering communication.

Our understandings of communication and therapeutic relationships need to be based in the perspectives and experiences with those living with communication impairments. This ensures our knowledge reflects the “human” needs of this patient group and takes into account the existential challenges they experience after stroke [Citation20,Citation21]. There has been limited explicit exploration of therapeutic relationships from the perspectives of those with communication impairment after stroke, with the exception of Lawton’s and Fourie’s work [Citation12,Citation18,Citation22]. Instead, much of the published research in the areas is embedded within studies of related phenomena such as engagement [Citation11], goal-setting [Citation23], and experiences of rehabilitation [Citation24,Citation25]. These experiences and knowledges are not consistently clearly visible, however, they have the potential to enhance our understandings of relationship-fostering communication and enhance theory and practice. For this reason, we sought to synthesise patients’ perceptions and experiences from across these two bodies of published research, foregrounding and consolidating knowledge to allow “a more comprehensive and integrated understanding” [Citation26,p.4] the phenomenon. Specially, this aim of this metasynthesis is to understand how, from the perspectives and experiences of patients, interpersonal communication influences therapeutic relationships between clinicians and people with communication impairment after stroke.

Methodology

This review uses a qualitative metasynthesis approach. This methodology is useful for developing new “layers of insight” [Citation27,p.1347] within existing published qualitative research; this “meta-interpretation” [Citation27,p.1347] brings a critically reflexive lens to produce an interpretive, somewhat theoretical account [Citation27]. The (re)interpretation of primary research is central to a quality metasynthesis. Each included paper is interrogated and analysed. Interpretive questions are asked to further understandings [Citation27]. Qualitative metasynthesis is used increasingly in health disciplines to generate new knowledge that both capture and extend existing knowledge [Citation26], some of which may not be easily visible, to inform research and clinical practice, and to develop the theoretical basis of praxis [Citation28].

Literature search

This qualitative metasynthesis used a systematic approach to search and identify relevant literature as one part of the search process. This approach is not without controversy. A purpose of a qualitative metasynthesis is to develop new insights into phenomena to inform theory and practice [Citation28]. Some argue that privileging the standard “systematic” process of strict search approaches, inclusion and exclusion criteria and so on can see process and rules privileged over diverse, relevant data which can allow for deep interpretation [Citation29] and can lead to undertheorised and overly descriptive accounts of the literature [Citation26]. That said, many metasyntheses use a systematic approach to identify data [e.g., Citation30,Citation31]. What appears critical is that these processes seek diversity, relevance and richness, and that the authors produce a critically reflexive interpretation of data [Citation29].

Literature were identified through three different techniques: a systematic search of the literature; consultation with experienced clinicians and researchers using social media and email; and citation searching of included papers from the systematic search and consultation. The systematic search was conducted using PsycINFO, CINAHL, MEDLINE and SCOPUS. Key search terms included a combination of: (1) diagnostic terms such as “aphasia” and “communication disability”; (2) terms related to the therapeutic relationship or communication; (3) clinicians, both generically and by job title; and (4) methodological terms, reflecting that only qualitative papers were included in this qualitative metasynthesis. The full search strategy is in Appendix 1. A librarian provided advice to help guide the search strategy [Citation32]. The initial search was performed in January 2018 and was updated in April 2019. Our consultation with experienced researchers took place in March 2018. References were updated prior to submission for publication; accordingly two papers [Citation18,Citation33] which were published online during or before April 2019 have been updated after being assigned to a specific volume/issue of the journal.

Inclusion criteria

Papers were included in this metasynthesis if they were qualitative empirical studies which explored experiences of people with communication disability after stroke and reported people’s perceptions and experiences of relationships and interactions with clinicians that give insight into therapeutic relationships in healthcare. Data from the included papers was only used if it reflected the insider experience of the person with communication impairment. If papers included data from multiple participants (e.g., person with aphasia and clinician), only the data that was clearly identified as coming from the person with communication impairment, or pertaining to people with communication impairment was included as data for this metasynthesis. Observational data, or interviews with other parties were not included for analysis. While many papers used words such as “relationship,” we constantly asked ourselves questions such as “does this paper provide insight into the interplay between communication and therapeutic relationships? and “does this paper explicate aspects of communication that affect relationships?” This helped ensure we were only including papers that were relevant to the research question [Citation29].

Papers were excluded if they:

solely discussed the use of supported communication techniques without providing insight into relational aspects of communication; or

only included observational data; or

included participants with and without communication disability, and it was not possible to identify data or findings that were specific to those with post-stroke communication impairments; or

discussed experiences of therapy or healthcare without specifically attending to communication and relationships;

focused on communication about therapeutic processes or information exchange without providing insight into the relational aspects of communication; or

were not published in English.

Search outcomes

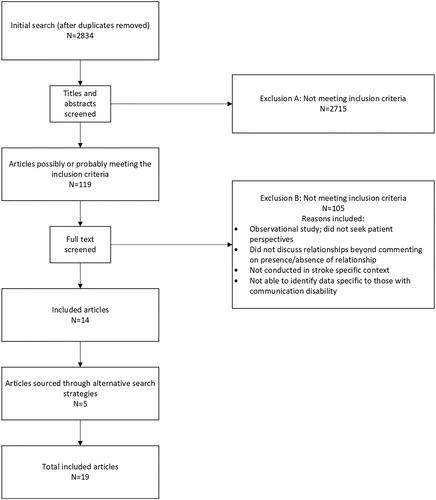

A flow diagram outlining the search process and outcomes is presented in . The second author completed the database search. The first author consulted clinicians and researchers. The search identified 2834 potentially relevant articles. After both authors screened abstracts and titles, 119 papers were identified as potentially eligible. After reviewing the full text of these articles, 14 met the inclusion criteria for inclusion. Levels of agreement were high with any disagreements resolved through discussion. A further 5 articles were identified through consultation with experienced researchers and citation searching. In total, 19 articles were included in this metasynthesis. A summary of the characteristics of these papers is provided in .

Table 1. Included papers.

Data extraction and analysis

Information about each paper were extracted into a table to summarise core material and to start the process of identifying the epistemological, methodological and social context of each study, a first step in the process of extracting and interpreting current knowledge [Citation27]. We used thematic analysis [Citation34] which saw us move through processes from familiarisation to constructing defined themes in an iterative, recursive process. We first familiarised ourselves with each paper by reading and rereading to gain an understanding of relational aspects of communication. Only material in the Findings and Discussion constituted “data” for this metasynthesis although the Introduction and Methods sections were critical in giving insight into social context of the research, the authors’ positioning, and the epistemology and methodology used. Material were coded, initially with relatively descriptive codes which stayed close to the data. For example, “the relationship between a client with aphasia and his or her therapists is undoubtedly the foundation of therapy” [Citation5,p.283] was initially coded as “relationship as foundational for treatment.” Codes from each article were then extracted and compared across papers. This saw us move to develop themes which captured codes and data across papers. In developing and refining these themes, we maintained analytic notes which reflected the questions we were asking of the data, a key early step in interpretation, and captured comparisons within and across the papers [Citation27]. We used thematic maps [Citation34] extensively to explore and interrogate relationships between codes and categories, within and across papers, and used tables to record our analysis, capturing themes and the supporting raw data. We reviewed themes by creating short descriptions of each theme and asking questions such as “is there sufficient data to support this theme?” and “how does this theme relate to another?” We also discussed our emergent findings with people experienced in therapeutic relationships and communication research and used the resulting discussion to help refine the themes. Finally, we defined and named the themes which are reported below.

Rigour

Multiple actions contributed to rigour. A robust search was completed, using multiple methods to identify appropriate literature. The researchers reviewed all potential papers together and came to agreement regarding their eligibility within the metasynthesis. We remained grounded in the data throughout the analysis approach, ensuring this was visible throughout analysis in our documents (e.g., thematic maps and tables) as well as in the final product [Citation34]. Emergent findings were discussed with subject experts in therapeutic relationships and communication disorders to help both refine and test the analysis. Consistent with Thorne’s [Citation26] guidance on qualitative metasynthesis, we have worked to produce a comprehensive integrative and interpretive account of the original studies, which moves the body of knowledge beyond that which was known from a simple reading of the original studies. This was aided by our prolonged engagement with the data, through examining data across the included studies, and by closely examining relationships between the data and the constructed themes. We explicitly attended to how our own backgrounds and knowledges (speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, therapeutic relationship researcher) shaped our readings of the data and influenced our interpretations. We acknowledge, consistent with Thorne [Citation26], that these backgrounds were invaluable in undertaking this work as they allowed us to engage in the deep thinking required in a qualitative metasynthesis.

Findings

We generated four themes which provide insight into how interpersonal communication influences therapeutic relationships between clinicians and people with communication impairment after stroke. These are: (1) Relationships provide the foundation for rehabilitation; (2) Different relational possibilities arise from “reading” the clinician; (3) Creating therapeutic relationships through validating interactions and connections; and (4) Creating therapeutic disconnections through invalidating, exclusionary interactions. Within our themes, we include direct quotes from the original papers; these include a combination of participant quotes and the authors’ analysis, reflecting that the data for this study were the Findings and Discussion sections of each paper.

Relationships provide the foundation for rehabilitation

Relationships appeared critical for people experiencing communication impairment after stroke. They provided stability in a time of instability. People came into healthcare in a vulnerable position, reporting a range of complex emotions such as feeling isolated [Citation12], being in shock, “terrified, even horror-stricken,” and “small and helpless” [Citation21,p.2507], as they realised the impact of the stroke. Depression was not uncommon [Citation22,Citation33]. The presence of a strong relationship, one in which the person felt understood and supported, and where they felt they could trust the clinician [Citation12,Citation18], could provide safety and security that could alleviate this emotional distress: “When a patient realises that the carer really wants to know and understand, he/she finds it easier for feel safe” [Citation21,p.2508]. The relationships could also support life reconstruction [Citation33], foster hope and positivity for the future [Citation35], help people persist in the face of fear and uncertainty [Citation11], and influence satisfaction with services [Citation36]. Relationships helped create an environment which helped people “make sense” of their situation after a stroke [Citation12]. The presence and strength of the therapeutic relationship could be critical in people having and developing their hope for the future [Citation5,Citation18] and helped people persist in the face of adversity [Citation22,Citation37]. When struggling with rehabilitation, one participant described how the relationship was important when struggling: “I hate what I have to do … but if it had to be with anyone, it should be with her” [Citation11,p.986], suggesting he felt comfortable and confident with the clinician. The presence of a relationship appeared to provide a supportive platform which enabled patients to engage, consistent with Worrall’s [Citation5] claim that “the relationship between a client with aphasia and his or her speech-language pathologist is undoubtedly the foundation of therapy” (p. 283). A person’s experience of rehabilitation appeared to be intrinsically linked with their perception of a relationship, with Worrall [Citation5] suggesting that it is through the relationship that the “tasks and activities of therapy are communicated, translated and experienced” (p.283). Some suggested the therapeutic relationships was the most memorable part of therapy, with one patient recalling her therapy saying: “all I can think of is her as a person … that sticks in my mind” [Citation5,p.285]. These findings challenge the notion of relationships being a “nice to have,” instead reinforcing that relationships have therapeutic value and may be critical in helping some people engage in rehabilitation.

Patients were not always ready to engage with clinicians or in rehabilitation, perhaps because of their emotional state, their hope that things would return to normal, or due to a lack of insight [Citation12]. However, the presence of a relationship could be a critical factor in helping people move from simply “tolerating” therapy to being engaged [Citation11], serving as a source of motivation [Citation18]. Lawton [Citation12] argued that in the early days of rehabilitation, the relationship was particularly crucial: “At this stage, participants spoken of needing more than professionalism; they needed compassion and empathy, a human connection” (p. 1407), likely due to the emotional sequalae of stroke. They described one patient’s experience: His initial disengagement was gradually eroded when he began to establish a connection with his therapist: “I didn’t particularly want to go and again I thought the whole thing was a bit pointless, but after two or three sessions I warmed up to this” [Citation12,p.1405].

A similar transition was evident in a study of engagement, with one patient describing how the relationship helped her move from “tolerating” therapy to being engaged, helping her “(get) through” as she adjusted to her post-stroke identity and a challenging rehabilitation process [Citation37]. It could be that the relationship (and the clinician through the relationship) could give a person encouragement that helped them engage and have the courage and confidence to try [Citation18,Citation22]. Several studies have demonstrated that engagement is co-constructed through relationships [Citation11,Citation12]; with the “development of a positive connection” [Citation12,p.1405] critical in supporting people to engage in rehabilitation. While these relationships commonly develop over time and through the provision of a caring, empathetic environment [Citation18], they appeared particularly critical in the early days after stroke, reflecting the emotional nature of that period in stroke recovery. Therapeutic relationships, and in particular, the interpersonal connection, also appeared important across the recovery trajectory for those with with more severe communication disability, and those with long-term rehabilitation and support needs, perhaps reflecting different psychosocial sequalae of stroke [Citation18].

Different relational possibilities arise from “reading” the clinician

Every patient-clinician interaction involves a relational process of some form, regardless of whether both parties are conscious of, or intentional about this. These relational processes are enacted through communication. These produce what communication theorists Gergen and McNamee describe as “relational configurations” [Citation38] depending on how communication occurs, and how the clinician’s verbal and non-verbal communication is received and interpreted by the person with communication impairment. Throughout the literature, it was clear that patients were active agents, surveilling the clinician and actively evaluating their behaviour and critically, the perceived intent and meaning which underpinned their interaction [Citation12,Citation21,Citation37]. Clinician qualities such as energy [Citation22] and passion [Citation37] were valued. Surveillance was evident even when patients were silent (or actively silenced), as described in one person’s description of being ignored by staff: “they scurry over and turn me … they don’t want to talk. I think they feel awkward because I couldn’t talk back” [Citation37,p.1401]. Such behaviours increased feelings of disengagement and isolation [Citation37]. People considered such behaviours reflected arrogance or ignorance [Citation39]. Even when silent and seemingly passive, patients were clearly “reading” the actions of staff, evaluating their (inter)actions and the cognitive and emotional states that may have underpinned this, and the intentions of the clinician. These interpretations then resulted in one of two key relational configurations: a therapeutic connection or a therapeutic disconnection.

Creating therapeutic relationships through validating interactions and connections

The therapeutic relationship developed through a sense of connection between the person with communication impairment and the clinician. This involved a sense of “meeting together” [Citation21]. The idea of connecting, or as Hjelmbleck described, said “being met through dialogue” [Citation40,p.97] was a common feature evident in narratives about patient-clinician relationships. The metaphors of meeting and journeying together were present in several studies [Citation21,Citation40], suggesting the connection involved the process of coming together into a therapeutic relationship and moving or working together throughout the episode of care. A therapeutic relationship was multi-dimensional [Citation22] with both a personal and a professional connection. It appeared important that there was rapport and a sense of “getting on” with the therapist [Citation5,Citation36]. Some people described this as similar to friendship [Citation5,Citation24] although this was not universally supported [Citation18]. Those who talked of friendship-like relationships appeared to be describing relationships that were not hierarchical [Citation36] and in which there was an even-ing of the power imbalance [Citation24]. This could come about by knowing something about the clinician working with them, having a sense of who the therapist is [Citation11,Citation12]. One person commented “I like to know what people do and what people are” [Citation11,p.986]. This (limited) openness could help develop a sense of connection and lessen power imbalances inherent in healthcare relationships. It was clear that the relationship also required a “professional” component [Citation5,Citation11,Citation18,Citation24,Citation36], with participants in Bright’s [Citation11] study saying the clinicians needed “‘professionalism and semi-professionalism [pointing to the heart]’, as though professionalism refers to technical knowledge and skill while semi-professionalism pertains to relational aspects of practice” (p. 986). The professional component was privileged by some in Lawton’s study [Citation18], who proposed individuals might privilege different aspects of the therapeutic relationship, possibly impacted by the severity and impact of the communication impairment.

People with communication impairment prioritised particular characteristics in their clinicians. Patients valued clinicians who they perceived as genuine and supportive [Citation5,Citation37], honest and trustworthy [Citation18,Citation23], knowledgeable and experienced [Citation23], caring [Citation18] and engaged [Citation37]. They placed importance on being “seen” and feeling heard by the clinician, that is, sensing the clinician had a good understanding of who they are and what they are going through, and were responding to this, individualising their interactions and subsequent healthcare [Citation5,Citation12,Citation18,Citation23,Citation24,Citation33]. This reflects a core form of collaboration for this population, seeking and listening to people’s narratives and working in a way that responds to these [Citation18]. Positive interactions, in which people felt they had a voice and that the voice was heard, were important in supporting adjustment and wellbeing [Citation33]. This gave a sense of being seen as an individual, as someone who has value, competence and intelligence, and whose needs, emotions and perspectives are important [Citation18,Citation23,Citation33]. This was evident in people describing feeling “genuinely valued and understood” and “cared for … as real people” [Citation5,p.283], something also described by Berg [Citation23]: “[They] emphasised the experience of being seen and heard by their speech pathologist as something they appreciated and valued” (p. 1125). Nyström suggested people with communication impairment wanted to “enter into a community where the patient recognises that the carer can – and really wants to – meet with him/her as an individual” [Citation21,p.2507]. Indeed, this was suggested to help support people as they worked to make sense of what had happened [Citation33]. This genuine desire to recognise and respond to someone’s personhood was apparent through the clinician’s communication and interactional style.

Patients valued clinicians who tried to communicate with them in a way which acknowledged and responded to their specific communication needs [Citation18,Citation21]. When patients perceived clinicians wanted to communicate with them this help validate them as a valued and legitimate communication partner. The clinician’s perceived intent could be evident in taking time and not rushing the patient, which one person suggested showed that they “had time for the patient” [Citation22,p.991]. The clinician’s attempts to communicate, even if unsuccessful, were positively received and interpreted as the clinician believing the patient had something important to contribute [Citation37,Citation41] which validated their expertise and experience [Citation41]. Worrall’s [Citation5] research reported people felt “more respected in their relationship with their therapist when an effort was made to inform and include them” (p. 291). Communication needed to be tailored to the communicative needs of the patient; if clinicians proceeded as though communication was “normal,” this was problematic and impeded relationships [Citation21,Citation39]. The fact that people tried to communicate was engaging and validating in and of itself. It gave people the sense that the clinician “could see something in me” [Citation12,p.1408] as one person with aphasia describe; this helped people have more confidence in themselves and their ability [Citation5]. This served to acknowledge and enhance an individual’s personhood at a time when their sense of identity was under threat [Citation12,Citation18,Citation33] as the attempt to communicate conveyed more than an interest in the person, but more fundamentally, demonstrated that the clinician recognised the person’s inherent competence [Citation12,Citation18,Citation21,Citation39].

For many people with communication impairment, relationship-building communication involved more than clinical talk, and more than simply using supported communication techniques [Citation11,Citation18,Citation33]. It involved non-verbal communication which seemed important for conveying care and support [Citation33,Citation37], and conversations about non-clinical matters [Citation11,Citation42]. Seemingly informal exchanges could “alleviate the awkwardness” of the different tasks [Citation42,p.898] and reinforce a sense of self as a competent individual [Citation21]. It seemed important that interactions were conversational and somewhat “natural” [Citation40] and authentic [Citation42] with a sense of flow and interaction throughout the exchanges, a sense of a living dialogue that was threaded through and across interactions [Citation11]. This approach to communication could be challenging when the patient and clinician had no apparent shared interest [Citation42]. Communication was key to sustaining relationships over time [Citation39]. Patients expected clinicians to modify their communication to include and support them rather than speak to others or to ignore them [Citation23,Citation39], and a failure to acknowledge the presence of communication difficulties was problematic [Citation21]. Communication attempts served to create a sense of relationship and togetherness which could lead to the development of a therapeutic connection.

People valued support from their clinicians [Citation5], having a sense that they were there “for them” [Citation24,p.153] and had a genuine interest in them “as a real person rather than simply another case to be managed” [Citation5,p.283]. One said the most important thing in therapy was that “they (the clinicians) were concerned about me” [Citation5,p.284]. This helped clinicians provide individualised care which responded to the needs, concerns and priorities of the individual [Citation5,Citation12]. “Concern” was also evident when clinicians closely “read” the person’s emotional state and responded to this through their actions and in conversation [Citation5,Citation11]. Clinicians needed to know when, and how much to push a patient [Citation12,Citation24], and how to maintain and foster hope [Citation5,Citation12]. Indeed, it was through communication that hope could be fostered or diminished [Citation43]. Making progress visible helped people maintain hope and enhanced their confidence [Citation12]. Responding to people’s psychological and emotional needs helped reduce their sense of isolation and enhanced trust in the clinician and in the rehabilitation process [Citation12]. Treating “the person” was an important factor in, and indicator of, a close therapeutic relationship [Citation12].

Creating therapeutic disconnections through invalidating, exclusionary interactions

Therapeutic disconnections could arise from the interaction (or lack thereof) between the clinician and patient. These disconnections could result from communication practices such as talking over, ignoring or excluding the patient, or by failing to make any communication accommodations [Citation11,Citation21,Citation23]. Infantilising communication was also reported by people with communication impairment, with one describing: “It’s the way you would talk to a little child and it strips you of your dignity somehow” [Citation44,p.142]. By not communicating or explicitly excluding patients from interactions, clinicians were said to “relinquish the opportunity to create a working alliance” [Citation21,p.2508]. Such behaviours conveyed a lack of attention to the person, their identity as an individual, and a lack of consideration of their communicative and psychosocial needs [Citation11,Citation21,Citation23]. These also suggested that clinicians did not value communicating with the person which became a relational barrier, reflecting that the patients were actively reading the clinician and their communication, and acted in response to this.

These negative communication practices could significantly impact on how people with communication impairment viewed themselves and their situation. They served to belittle and dehumanise people [Citation33], reduce their standing and power within the relationship, reinforce a lack of personhood [Citation44] and reinforce negative emotions [Citation21]. Such behaviors were perceived by the patient as meaning they [the patient] were lacking intelligence, they were incapable and that they were being rendered invalid as a human being [Citation36,Citation43]. A lack of communicative effort reinforced the sense of isolation and disability [Citation21,Citation37]. Patients suggested the resulting sense of inferiority and low self-esteem could be seen as worse than the impairment itself [Citation21]. These behaviours could “alienate [the patient] from the caring situation” [Citation21,p.2507] with negative implications for the therapeutic relationship and engagement in rehabilitation.

Patients commonly reported being excluded from interactions when others without communication impairments were present [Citation44,Citation45]. Failing attend to a patient’s requests for assistance with basic needs was isolating and left people vulnerable [Citation33]. People talked of being rendered invisible [Citation37] when they were talked over and talked about, something they considered humiliating [Citation21]. This was experienced in interactions between clinicians who talked about the patient as though they were not present [Citation21], and when clinicians interacted with family members rather than the patient [Citation44]. While aware this was happening, patients were often unable to challenge this due to their communication impairment. This further reinforced their sense of isolation and incompetence [Citation37,Citation45]. It is important to note that patients were sometimes happy for clinicians to talk to others, but what seemed critical was that this was negotiated and that the patient was able to maintain sense of agency and personhood throughout [Citation39].

Therapeutic disconnections could also result from clinician-centred interactions in which clinicians were perceived to be focused on the job they consider they need to do, and in the process, the person with communication impairment was unseen and unheard. People with communication impairment reported instances of being treated as a “task” or “just a number” [Citation33,p.3], with clinicians seen to be going through the motions, foregrounding what they or their service required [Citation5,Citation33,Citation37]. One patient described this saying “they come in to do a job but they don’t know me” [Citation37,p.1401], and accordingly, they were “perceived to be disconnected or disengaged with [the person] as an individual” [Citation37,p.1402]. It was notable that patients once again detailed how they read the clinicians’ behaviour, considering the reasons for such behaviour. One commented: “After my aphasia, she never talked to me again and avoided eye contact. I understood that she was afraid” [Citation21,p.2506]. Some patients took responsibility for a lack of communication, due to their own inability to communicate [Citation37,Citation45]. When patients saw the clinician as being disengaged and focused on their own priorities, they reported feelings of frustration, hurt, anger and disrespect as the practitioner’s disengaged behavior [Citation21,Citation37,Citation45]. When practitioners failed to communicate, or there was a lack of perceived attempts to communication, this could contribute to disengagement and therapeutic disconnection on the part of the patient and possibly the clinician [Citation37], an uncomfortable, tension-filled relationship [Citation5], or self-discharge from services [Citation23].

Discussion

Interpersonal communication is inherently entwined with the development and maintenance of the therapeutic relationship between the person with communication impairments and their clinicians. Patients are active as this relationship develops, reading the clinician’s communication as well as the intent and attitudes behind their communication. Based on this reading and whether they perceive it renders them valid or (in)valid, different relational possibilities are created. Which type of connection occurs had consequences for how the patient engages in healthcare services, and potentially, for their treatment outcomes, although the latter is outside the scope of this review.

In many ways, the finding that therapeutic connections are fundamental in rehabilitation is not a surprising finding. A body of literature highlights the crucial role of relationships in enhancing patient experience and engagement in rehabilitation [Citation1,Citation9,Citation46] while there is a growing body of evidence that relationships impact on treatment outcomes [Citation1,Citation3,Citation47]. This review identified that relatively little research has explored the perspectives of people with acquired communication impairments. In synthesising this literature, we can clearly say that the connections between patients and clinicians matter. These connections are relationally produced and shaped by people’s perceptions of themselves and others. This supports a socio-relational model of rehabilitation, which holds that rehabilitation is inherently relational and that social interaction and the rehabilitation environment influence people’s sense of self, their feelings and behaviour [Citation48]. Similarly, it resonates with the SENSES framework which propose that people require a sense of security, continuity, belonging, purpose, achievement, and significance in care, and that this is achieved through interdependent relationships between patients, family and staff [Citation49]. We suggest that therapeutic connections are particularly important in light of the existential challenges people experience after a stroke [Citation50], including the changes in sense of self and psychosocial well-being that are common after stroke [Citation51–53] which can be exacerbated or disproportionately common in people with communication impairment [Citation51,Citation54]. Given the central role of therapeutic connections in rehabilitation, and the potential implications of a therapeutic disconnection, we argue relationships are a legitimate focus for time and attention and needed to be valued not just by clinicians, but within organisational structures and culture, and seen as a form of fundamental care [Citation55,Citation56].

Communication functioned as a critical mechanism in developing therapeutic connections. This is a relational form of communication that was inherently interactional and social in nature. Indeed, the core features of this relational communication are strikingly similar to what people with aphasia value in social interaction (i.e., with friends and family, not clinicians) – connectedness, humour, small talk, and some revelation of the self [Citation57]. What is notable about relational communication is what it accomplishes. Communication does not “just” allow people to access and participate in healthcare [Citation58] or serve to acknowledge competence [Citation19], common desired outcomes of communication. It also actively constructs an individual’s competence and personhood [Citation20,Citation59], creates different relational configurations (connected or disconnected), and facilitates engagement in rehabilitation [Citation11]. Arguably, relational communication could be considered a therapeutic intervention in its own right, worthy of explicit attention in education and practice [Citation60]. Relational communication requires particular actions and attitudes from clinicians and requires these intentions to be received and “felt” by patients, a form of joint action [Citation61]. Viewing communication as relational and co-constructed should prompt reflection on how the clinician’s actions are being interpreted, internalised and responded to by the patient, and how their social and relational needs are being met [Citation50]. This sits alongside other forms of reflection considered important in relational approaches to care, including reflection on the feelings of discomfort and uncertainty that can occur in these interactions [Citation20], and reflection on how the clinician’s own engagement is impacting on the patient [Citation37]. It is clear that relational communication is multi-faceted, personalised and responsive to the individual person, a sophisticated way of working and being.

Viewing communication as inherently relational raises questions about how this is, or could be, considered in communication partner training. This training, usually led by speech-language therapists, is designed to support clinicians and other communication partners to improve their communication with those with communication impairments [Citation58]. Such training commonly addresses their knowledge and skills, but it does not appear that relational communication is consistently addressed in communication partner training for clinicians [Citation20,Citation58]. While these principles are evident in some approaches [Citation59,Citation62], many reflect a “professionalised technical discourse” [Citation63,p.1256] based on the knowledge and skills that speech-language therapists’ consider others need such as knowledge about aphasia, and specific communication techniques [Citation63]. There is a risk that such training might (unintentionally) suppress relational aspects of communication and may indeed reinforce a “practitioner-centred” approach to communication and possibly, to care [Citation11,Citation64]. We echo the calls of others who suggest that clinicians’ communication needs to be built on a deep understanding of the fundamental, existential needs of people with communication impairment [Citation20] that is based on, and explicitly supports people to attend to the “experiences of insiderness” of those with communication impairment [Citation63,p.1260], and that supports clinicians to reflect not just on their communicative behaviours, but the attitudes, values and feelings that these may represent.

Communication and relationships are demonstrably important when working with people with communication impairments in supporting them to engage and to develop a strong self-identity post-stroke. However, these interpersonal aspects of care are not always prioritised in clinical practice [Citation11,Citation65,Citation66] and indeed, clinicians report many challenges in communicating with this population which can lead to them restricting their interactions [Citation15]. That is not to say that clinicians do not value them or consider important, rather, that they are “rendered invisible and devalued” [Citation55,p.2] in biomedical care models and in health systems which are focus on technical aspects of care, patient throughput, and readily measurable outcomes, arguably at the expense of relational models of care that value meaningful engagement with patients [Citation9,Citation55]. In speech-language therapy, particularly in acute care, communication management is often deprioritised for dysphagia [Citation67]. Despite evidence of the value of relationships and communication in stroke, they are rarely evident in stroke guidelines [Citation68]. These aspects of care are recognised as critical to “fundamental care,” a model used primarily in nursing to explain patients’ fundamental needs in healthcare: physical, psychosocial (which includes communication) and relational [Citation69]. However, the clinical context people work in is busy and complex. Communication is recognised as a leading form of “care” that nurses “left undone” in times of acuity and busyness [Citation66]. Staff report a lack of knowledge, skill and time which impacts on their communication [Citation15]. This reflects that clinicians’ ways of working are strongly influenced by the contexts they work in. We urge against attributing communication and relational breakdowns solely to the clinician (or indeed, to the patient). If clinicians are to communicate in ways that facilitate the development of therapeutic connections, it is critical that this work is both valued and enabled by the systems and structures that they work within [Citation9,Citation70], supporting Pound and colleagues’ call for humanised environments, not just humanised interactions [Citation20].

This metasynthesis provides a comprehensive analysis of the literature which details the interplay of communication and therapeutic relationships for people with communication impairment after stroke, from the perspectives of patients. It is possible we missed relevant papers in our search given that material may be embedded within papers on related topics and not captured through the search process which focused on titles, abstracts and keywords. However, the processes of involving a librarian, consulting with experts, and citation searching means we have likely retrieved the relevant papers. Gathering data from other patient-led sources such as books or blogs would likely bring different perspectives direct from those with communication impairments. This work could be valuable in developing deeper understandings in the future. This paper (re)presents perspectives gathered and interpreted by researchers. Some papers only had small sections of data (i.e., material in the Findings and Discussion) that spoke to the interplay of communication and therapeutic relationships, reflecting that the primary purpose of such studies was often to explore related phenomenon (e.g., patient satisfaction [Citation36]). Therefore, the analysis drew more heavily on papers which explored therapeutic relationships and/or interpersonal communication in more depth as they offered more comprehensive data (e.g., studies of engagement [Citation11] and therapeutic relationships [Citation12]) and allowed for more robust analysis and interpretation. We sound caution about the claims one might make as a result of this research. For example, whilst we provide evidence that communication is a core component in developing therapeutic relationships, it is important to note that it is only one component of a therapeutic relationship. Other research highlights the importance of family collaboration [Citation7], working on areas that matter to patients in the therapy process [Citation11], in a way that is consistent with the patient’s preferences [Citation11,Citation18]. Of course, this review did not intend to identify all the factors that contribute to therapeutic relationships, instead choosing to explicate the role of communication in therapeutic relationships, building the evidence base to support clinicians and services to value and prioritise relational communication, and expanding our knowledge of what relational-fostering communication involves.

Given that communication can shape a patient’s engagement in rehabilitation [Citation11] and their sense of self and well-being following stroke [Citation33,Citation40], it is critical that this is attended to in clinical practice. Our description of relationship-enhancing communicative practices will support clinicians to critically reflect on their own communication, identifying which elements are most evident their own practice. We urge clinicians to also reflect on the circumstances which may facilitate, or hinder this approach to communication, recognising that the context of care and workplace structures and pressures influence how people work [Citation15]. It has been suggested that clinicians’ communicative practices are influenced by values, knowledge and skills [Citation11,Citation20,Citation71]. Relationship-fostering communication requires clinicians to value the humanity and personhood of those with communication impairments and value therapeutic relationships as foundational in rehabilitation [Citation5,Citation20,Citation71]. It requires them to be able to prioritise these aspects when working in healthcare contexts which often prioritise other aspects of care [Citation67,Citation71], and requires that they have the knowledge and skills to communicate in this way [Citation20,Citation71]. Speech-language therapists have a crucial role in supporting colleagues to work with those with communication impairment. We suggest that such support and training should attend not just to communicative techniques, which are clearly important, but also foreground the perspectives and experiences with those with communication impairment. Training should aim to enhance knowledge of why communication matters for personhood and relationships, and should support clinicians to reflect on the values which underpin and are enacted through their own communicative practice. The findings should give confidence to clinicians who value communication and relationships in stroke care and may support them in advocating for service design and delivery that allows clinicians to prioritise these aspects of practices.

Conclusions

This review explicates how communication and therapeutic relationships are entwined. It demonstrates how interactions can produce different relational possibilities. Through interaction, people with communication impairment can be constructed as valued or invalid communicators; this then informs what therapeutic connections and disconnections arise. Rehabilitation providers from all disciplines can benefit from critically reflecting on how their interactions can enhance or diminish a therapeutic connection with their patient, whilst also acknowledging that these interactions and ways of working are influenced by the context they work in. Improving interactions and connections can facilitate engagement in rehabilitation and have an important role in supporting people’s psychosocial wellbeing and ability to live well after stroke, a primary outcome of rehabilitation [Citation72].

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kayes NM, McPherson KM, Kersten P. Therapeutic connection in neurorehabilitation: theory, evidence and practice. In: Demaerschalk B, Wingerchuk D, Uitdehaag B, editors. Evidence-based neurology. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 303–318.

- Kayes NM, Mudge S, Bright FAS, et al. Whose behaviour matters? Rethinking practitioner behaviour and its influence on rehabilitation outcomes. In: McPherson K, Gibson B, LePlege A, editors. Rethinking rehabilitation. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2015. p. 249–271.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1099–1110.

- Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Human technologies in rehabilitation: 'Who' and 'How' we are with our clients. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(22):1907–1911.

- Worrall L, Davidson B, Hersh D, et al. The evidence for relationship-centred practice in aphasia rehabilitation. JIRCD. 2011;1(2):277–300.

- Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychother Theor Res Pract. 1979;16(3):252–260.

- Bishop M, Kayes N, McPherson K. Understanding the therapeutic alliance in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1651909

- Miciak M, Mayan M, Brown C, et al. The necessary conditions of engagement for the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: an interpretive description study. Arch Physiother. 2018;8:3.

- Lawton M, Haddock G, Conroy P, et al. Therapeutic alliances in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-ethnography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(11):1979–1993.

- Kayes NM, Cummins C, Theadom A, et al., editors. What matters most to the therapeutic relationship in neurorehabilitation? European Health Psychology Society. Aberdeen (Scotland): The European Health Psychologist; 2016.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, McPherson KM, et al. Engaging people experiencing communication disability in stroke rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;53(5):981–994.

- Lawton M, Haddock G, Conroy P, et al. People with aphasia’s perception of the therapeutic alliance in aphasia rehabilitation post stroke: a thematic analysis. Aphasiology. 2018;32(12):1321–1397.

- Dickey L, Kagan A, Lindsay P, et al. Incidence and profile of inpatient stroke-induced aphasia in Ontario, Canada. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(2):196–202.

- Hemsley B, Georgiou A, Hill S, et al. An integrative review of patient safety in studies on the care and safety of patients with communication disabilities in hospital. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(4):501–511.

- Carragher M, Steel G, O’Halloran R, et al. Aphasia disrupts usual care: the stroke team’s perceptions of delivering healthcare to patients with aphasia. Disabil Rehabil. 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1722264

- Hersh D, Godecke E, Armstrong E, et al. Ward talk": nurses' interaction with people with and without aphasia in the very early period poststroke. Aphasiology. 2016;30(5):609–628.

- Gordon C, Ellis-Hill C, Ashburn A. The use of conversational analysis: nurse-patient interaction in communication disability after stroke. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(3):544–553.

- Lawton M, Haddock G, Conroy P, et al. People with aphasia's perspectives of the therapeutic alliance during speech-language intervention: a Q methodological approach. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;22(1):59–69.

- Kagan A. Revealing the competence of aphasic adults through conversation: a challenge to health professionals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 1995;2(1):15–28.

- Pound C, Jensen LR. Humanising communication between nursing staff and patients with aphasia: potential contributions of the Humanisation Values Framework. Aphasiology. 2018;32(10):1225–1249.

- Nyström M. Professional aphasia care trusting the patient's competence while facing existential issues. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(17):2503–2510.

- Fourie RJ. Qualitative study of the therapeutic relationship in speech and language therapy: perspectives of adults with acquired communication and swallowing disorders. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2009;44(6):979–999.

- Berg K, Askim T, Balandin S, et al. Experiences of participation in goal setting for people with stroke-induced aphasia in Norway. A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(11):1122–1130.

- Boutin-Lester P, Gibson RW. Patients' perceptions of home health occupational therapy. Aust Occup Ther J. 2002;49(3):146–154.

- Brady MC, Clark AM, Dickson S, et al. Dysarthria following stroke: the patient's perspective on management and rehabilitation . Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(10):935–952.

- Thorne SE. Metasynthetic madness: what kind of monster have we created? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(1):3–12.

- Thorne SE. Qualitative metasynthesis: a technical exercise or a source of new knowledge? Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1347–1348.

- Levack WMM. The role of qualitative metasynthesis in evidence-based physical therapy. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17(6):390–397.

- Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(6):e12931–e12931.

- Levack WMM, Kayes NM, Fadyl JK. Experience of recovery and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(12):986–999.

- Hammell W. K. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(2):124–139.

- Beverley CA, Booth A, Bath PA. The role of the information specialist in the systematic review process: a health information case study. Health Info Libr J. 2003;20(2):65–74.

- Clancy L, Povey R, Rodham K. "Living in a foreign country": experiences of staff-patient communication in inpatient stroke settings for people with post-stroke aphasia and those supporting them. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):324–334.

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, et al. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton Rogers W, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. 2nd ed. London (UK): SAGE; 2017. p. 17–37.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, McCann CM, et al. Hope in people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2013;27(1):41–58.

- Tomkins B, Siyambalapitiya S, Worrall L. What do people with aphasia think about their health care? Factors influencing satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Aphasiology. 2013;27(8):972–991.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, Cummins C, et al. Co-constructing engagement in stroke rehabilitation: a qualitative study exploring how practitioner engagement can influence patient engagement. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(10):1396–1405.

- McNamee S, Gergen KJ. Introduction. In: McNamee S, Gergen KJ, editors. Therapy as social construction. Newbury Park (CA): SAGE Publications; 1992.

- Burns M, Baylor C, Dudgeon BJ, et al. Asking the stakeholders: perspectives of individuals with aphasia, their family members, and physicians regarding communication in medical interactions. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015;24(3):341–357.

- Hjelmblink F, Bernsten CB, Uvhagen H, et al. Understanding the meaning of rehabilitation to an aphasic patient through phenomenological analysis – a case study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2007;2(2):93–100.

- Young A, Gomersall T, Bowen A. Trial participants' experiences of early enhanced speech and language therapy after stroke compared with employed visitor support: a qualitative study nested within a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(2):174–182.

- Hersh D, Wood P, Armstrong E. Informal aphasia assessment, interaction and the development of the therapeutic relationship in the early period after stroke. Aphasiology. 2018;32(8):876–901.

- Mackay R. Tell them who i was’[1]: the social construction of aphasia. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(6):811–826.

- Dickson S, Barbour RS, Brady M, et al. Patients' experiences of disruptions associated with post-stroke dysarthria. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008;43(2):135–153.

- Stans SEA, Dalemans R, de Witte L, et al. Challenges in the communication between 'communication vulnerable' people and their social environment: an exploratory qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):302–312.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, Worrall L, et al. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(8):643–654.

- Stagg K, Douglas J, Iacono T. A scoping review of the working alliance in acquired brain injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(4):489–497.

- Douglas J, Drummond M, Knox L, et al. Rethinking social-relational perspectives in rehabilitation: Traumatic brain injury as a case study. In: McPherson K, Gibson B, LePlege A, editors. Rethinking rehabilitation. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2015. p. 137–161.

- Nolan MR, Davies S, Brown J, et al. Beyond person-centred care: a new vision for gerontological nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(3a):45–53.

- Loft MI, Martinsen B, Esbensen BA, et al. Call for human contact and support: an interview study exploring patients' experiences with inpatient stroke rehabilitation and their perception of nurses' and nurse assistants' roles and functions. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(4):396–404.

- Lincoln NB, Kneebone II, Macniven JAB, et al. Psychological management of stroke. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- Satink T, Cup EH, Ilott I, et al. Patients' views on the impact of stroke on their roles and self: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(6):1171–1183.

- Salter K, Hellings C, Foley N, et al. The experience of living with stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(8):595–602.

- Mitchell AJ, Sheth B, Gill J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of post-stroke mood disorders: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:48–60.

- Feo R, Kitson A. Promoting patient-centred fundamental care in acute healthcare systems. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:1–11.

- Kitson AL, Dow C, Calabrese JD, et al. Stroke survivors' experiences of the fundamentals of care: a qualitative analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(3):392–403.

- Davidson B, Worrall L, Hickson L. Exploring the interactional dimension of social communication: a collective case study of older people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2008;22(3):235–257.

- Cruice M, Blom Johansson M, Isaksen J, et al. Reporting interventions in communication partner training: a critical review and narrative synthesis of the literature. Aphasiology. 2018;32(10):1135–1166.

- Kagan A. Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology. 1998;12(9):816–830.

- Priebe S, McCabe R. Therapeutic relationships in psychiatry: the basis of therapy or therapy in itself? Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20(6):521–526.

- Gergen KJ. Relational being: beyond self and community. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Sorin-Peters R, McGilton KS, Rochon E. The development and evaluation of a training programme for nurses working with persons with communication disorders in a complex continuing care facility. Aphasiology. 2010;24(12):1511–1536.

- Horton S, Pound C. Communication partner training: re-imagining community and learning. Aphasiology. 2018;32(10):1250–1265.

- Hiller A, Guillemin M, Delany C. Exploring healthcare communication models in private physiotherapy practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1222–1228.

- Lawton M, Sage K, Haddock G, et al. Speech and language therapists' perspectives of therapeutic alliance construction and maintenance in aphasia rehabilitation post-stroke. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;53(3):550–563.

- Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, et al. Care left undone' during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):116–125.

- Foster A, O’Halloran R, Rose M, et al. Communication is taking a back seat": speech pathologists’ perceptions of aphasia management in acute hospital settings. Aphasiology. 2016;30(5):585–608.

- Bright FAS. Reconceptualising engagement: a relational practice with people experiencing communication disability after stroke. Auckland: Auckland University of Technology; 2016.

- Feo R, Conroy T, Jangland E, et al. Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: a modified Delphi study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2285–2299.

- McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred practice in nursing and healthcare: Theory and practice. Newark (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

- Byng S, Cairns D, Duchan J. Values in practice and practicing values. J Commun Disord. 2002;35(2):89–106.

- Kirkevold M, Bronken BA, Martinsen R, et al. Promoting psychosocial well-being following a stroke: developing a theoretically and empirically sound complex intervention. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(4):386–397.

Appendix 1.

Search strategy

(aphasia OR dysphasia) OR dysarthria OR (apraxia OR dyspraxia) OR (cognitive-communication) OR (“communication disabil*” OR “communication difficult*” OR “communication impair*”)

AND

(care OR car*) OR (relationship OR “therapeutic relationship” OR “therapeutic alliance” OR “working alliance”) OR presence OR communication OR conversation OR interaction OR rapport

AND

("speech therapist" OR "speech-language therapist" OR "speech language therapist" OR "speech pathologist” OR “speech-language pathologist” OR “speech language pathology”) OR nurse OR assistance OR psychology* OR psychiatry* OR (“social work*”) OR therapist* OR (“health professional" OR "healthcare professional" OR "health care provider” OR “healthcare provider”) OR “health practition*” OR (physician OR doctor) OR (physiotherapist OR “physical therap*”) OR “occupational therap*” OR practitioner*

AND

Qualitative OR “grounded theory” OR phenomenology OR “discourse analysis” OR “conversation analysis” OR “thematic analysis” OR “qualitative descriptive” OR “interpretive descripti*” OR interview* OR “focus group” OR observation* OR review