Abstract

Purpose

Limb salvage surgery is a surgical procedure for tumour resection in bone and soft-tissue cancers. Guidelines aim to preserve as much function and tissue of the limb as possible. Surgical outcome data is routinely available as part of surgical reporting processes. What is less known are important non-oncological outcomes throughout recovery from both clinical and patient perspectives. The objective of this review was to explore non-oncological outcomes in patients diagnosed with sarcoma around the knee following limb salvage surgery.

Materials and Methods

A scoping review methodology was used, and results analysed using CASP checklists.

Results

Thirteen studies were included and following appraisal and synthesis, three themes emerged as providing important measures intrinsic to successful patient recovery: (1) physical function, (2) quality of life and, (3) gait and knee goniometry. Specifically, patients develop range of motion complications that alter gait patterns and patients often limit their post-operative participation in sport and leisure activities.

Conclusions

This study has shown the importance of exploring confounding factors, adopting a holistic view of patient recovery beyond surgical outcomes, proposing evidence-based guidance to support and inform healthcare providers with clinical decision-making. This review highlights the paucity and lack of quality of research available, emphasising how under-represented this population is in the research literature.

Patients having undergone LSS often have limited participation in sport and leisure activities.

Patients can develop range of motion complications, such as flexion contracture or extension lag, which may affect the pattern of gait.

Clinical consideration should be given to walking ability and gait patterns during the rehabilitation phase to prevent poor functional outcomes during recovery.

Variation of treatment protocols, outcome measurement and rehabilitative care has been identified as important in predicting the outcomes in recovery from LSS procedures.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Bone cancer is considered a rare form of mesenchymal malignancy and is a life-threatening disease [Citation1]. The incidence of sarcoma is higher in men than women, occurring in 5.4 per million men and 4.0 per million women each year, and the predominant population is young adults, teenagers and children [Citation2,Citation3]. This paper will focus on knee sarcoma: osteosarcoma, which forms within bone cells, is the most common type of bone malignancy, representing 56% of bone cancer cases, followed by Ewing’s sarcoma, a malignancy formed within the bone or, in rare cases, the soft tissue around the bone, representing 34% of bone cancer cases [Citation3]. Osteogenic sarcoma arises in the metaphyseal end plates of the long bones in the extremities; two-thirds of cases affect the lower extremities, with the femur being the most common location (42%), followed by the tibia (19%) [Citation3–5]. Surgical management is standard care for sarcoma with amputation and disarticulation historically recognised as the main surgical options. However, due to medical advancements in imaging techniques, chemotherapy and radiation, surgical interventions have shifted from ablative surgery (such as amputation) to limb salvage or sparing techniques [Citation6–9]. Limb salvage surgery (LSS) is one such technique and is recommend by Steinau and colleagues [Citation10] for the treatment of sarcoma when used to locally control the disease, preserving unaffected tissue to maintain or restore limb function. From a medical viewpoint, success rates for LSS are considered high, based on a 70% 5-year survival rate of non-metastatic sarcoma patients and the local control of tumours. Several factors play important roles in the decision-making phase, including the age of the patient, skeletal maturity, response to treatment, tumour size and extent, which are reportedly correlated to surgical success and outcomes [Citation11,Citation12]. While surgical outcomes and survival rates are important oncological outcomes to report, other outcomes are also likely to be important to the patient beyond survival and into recovery.

LSS procedures can vary based on patient needs, however generally surgery occurs via a wide, local excision of the tumour and can involve autologous grafts, endoprostheses with metal implants, or a combination of both [Citation13,Citation14]. The knee joint is the most common location for lower extremity sarcoma involving the distal femur and proximal tibia. Due to the functional movement, complexity of the knee joint anatomy and the requirement for weight bearing, the knee is considered a challenging site for successfully restoring function and minimising impairment. Surgical procedures involving the knee can be accomplished using an intra-articular technique if the tumour size is under control; however, if the tumour has spread to adjacent tissue, then extra-articular resection may be required to maintain metastasis-free tissue [Citation13,Citation15,Citation16].

Functional and Quality of Life (QoL) outcomes are crucial in any surgical technique performed to patients with sarcoma [Citation17]. These non-oncological factors can be assessed by using variant subjective and objective outcome measures in order to provide evidence of success levels and associated complications of a surgical intervention and its correlation with function and quality of life afterward [Citation18]. Some papers had conducted meta-analysis and systematic review of these aspects with sarcoma patients in general [Citation19–21]. However, no review of these non-oncological outcomes has been conducted specifically to limb salvage surgery as a treatment of sarcoma around the knee in order to synthesise this evidence to help support and inform clinical decision-making. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review is to identify and synthesise knowledge on non-oncological outcomes associated with LSS in patients with sarcoma around the knee. The outcome of this scoping review will summarise and synthesise the evidence with the aim of informing clinical decision making and identifying future research priorities.

Methods

There is a requirement to develop comprehensive, evidence-based guidance to support and inform healthcare providers with clinical decision-making [Citation22]. While traditionally scoping reviews were defined by the absence of an assessment of quality, more recent methodological work in this area, extending the original framework of Arksey and O’Malley [Citation23] has seen the inclusion in scoping reviews as essential for providing “research that in itself can be disseminated to others in a way that is useful for practice or policymaking and for future researchers.” [Citation24,Citation25]. As the principle of this review is to provide implications for practice, specifically rehabilitation where there is limited clinical guidance, a quality assessment is also included. In this review, the principles and approaches suggested by Booth et al. [Citation26] were applied to identify reliable studies and to synthesise those results in a rigorous way. This approach applies a detailed search question and strategy, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, and explicit criteria for assessing the validity of the eligible studies based on the scope of the review [Citation27].

The following is aligned to Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews: identifying the research question [Citation23]. The research question underpinning this review was developed with the PICO table () and defined as “What are the non-oncological outcomes following LSS of patients with sarcoma around the knee?”. Further, the PICO table was used to determine appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria for the search strategy [Citation28], and this refers to Arksey & O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews [Citation23]: study selection; specifically, the outcomes chosen were driven by clinical decision making and represent the Author’s experiences in managing clinical outcomes for this complex patient group.

Table 1. PICO Table to define the research question and support the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review.

The following refers to Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews: identifying relevant studies [Citation23]. The European Society for Medical Oncology [Citation29] osteosarcoma clinical recommendations and guidelines document is recognised in the field of treating sarcoma; therefore, it was identified in this literature review as the standard of care. The guidelines were reviewed and adapted to bone and soft-tissue cancer in 2018 through a partnership between the European Reference Network for Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) and the European Reference Network for Paediatric Oncology (PaedCan) and were accepted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). These primary clinical guidelines influenced this literature review by shaping the search strategy to focus on studies published from 2009 onward.

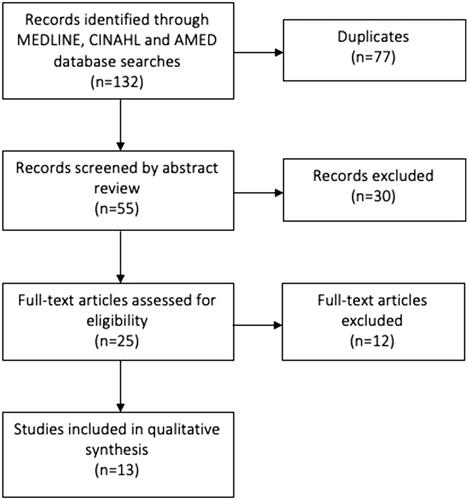

An initial search of the COCHRANE database as a specialist database for high-quality systematic reviews as recommended by Aveyard [Citation30]. This step was conducted using the search terms, Boolean operators and truncations identified in , which were later used for the other databases. After no matching systematic reviews were found in the COCHRANE database, a literature search was conducted in September 2020 in three databases: MEDLINE, CINAHEL and AMED. Restrictions were applied, such as date, English language articles and full-text access; the search results are recorded in the PRISMA flowchart (). A total of 132 articles were returned.

Table 2. Search terms included for the review.

All duplicates were removed (N = 77), and inclusion and exclusion criteria in were applied on the remaining 55 articles, providing the relevant studies. The abstracts were reviewed by an Author [NA], whereupon 30 were excluded. Full-text versions of the remaining 25 articles were re-assessed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Twleve articles were finally excluded for three main reasons; (1) irrelevant intervention or insufficient outcome measures, and (2) outcome content did not match the scope of this review.

Table 3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the review.

The remaining 13 articles were included in the review. The included articles were mostly observational and longitudinal studies due to the rarity of this condition. Due to the variability of the methods used in the included studies, the CASP tool was used for cohort and case–control studies [Citation31] and the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist was used for cross-sectional studies and case series [Citation32]. These are valid, critical appraisal tools, and are recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Citation33] and Sanderson et al. [Citation34].

Results

The results presented follow Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews: charting the data, and are described below and presented in the format of a narrative review, recommend by Arksey and O’Malley [Citation23] in order to extract contextual information and add value to this under-researched area.

Papers published between 2009 and 4 September 2020 were considered for this literature review resulting in 13 papers. A summary of the relevant papers is provided in and describe both general information about the study and specific information to answer the research question. Eleven papers were retrospective and one prospective [Citation17]. The 11 retrospective articles included four cohort studies [Citation18,Citation19,Citation35,Citation42], two case-control studies [Citation20,Citation37], two analytical cross-sectional studies with retrospective data [Citation21,Citation35,Citation38] and three retrospective chart reviews [Citation39,Citation40,Citation43].

Table 4. Review results: articles identified from methods described.

The overall study population was heterogeneous for age, stage and type of tumour, associated treatment (e.g., chemotherapy), type of endoprostheses used, surgical techniques, presence of a comparison group and the type of comparison, (ablative surgery or a healthy control group). Most studies described age variation and two papers were dedicated to paediatrics and young adults [Citation18,Citation21].

The study location varied; five studies were from Asia; China [Citation18,Citation40,Citation43], Japan [Citation39] and Malaysia [Citation38] and five from Europe; Netherlands [Citation17,Citation21], United Kingdom [Citation35], Germany [Citation36] and Spain [Citation37]. The remaining papers were from the United States [Citation19] and Australia [Citation20,Citation41]. Most of the papers clearly addressed compliance with ethical standards of research and informed consent was obtained in all studies when needed. However, four papers [Citation20,Citation35,Citation36,Citation41] did not state whether ethical approval was obtained prior to conducting the research and accessing patient data, thus were not aligned to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [Citation44] for medical research involving human subjects.

For transparency and ease of comparison, summarises each paper with respect to the thematic content therein. The following thematic process follows Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews: Collating, summarising and reporting the results [Citation23]. were considered to be the most relevant to the research question. Themes were chosen that were considered most relevant to the research question.

Table 5. Summary review of articles with respect to three themes.

Physical function

Functional outcomes were measured in all of the included papers using various outcome measures and scores. The outcomes measured were physical function, walking distance, walking speed and functional mobility, utilising both disease-specific and generic outcome measures. Three papers used objective measures alongside a subjective measure, and these studies were the most focused on functional outcomes due to their use of multiple measures [Citation17,Citation19,Citation21]. However, it is important to stipulate that none of the functional measures take into account the patient’s perspective. Further information on the discrepancy between patient- and clinician-reported function in this population is reported in Janssen et al. [Citation45]. The remaining studies relied on a subjective measure for the functional outcome. The overall Musculoskeletal Tumour Society scoring system (MSTS) mean scores in all 10 papers was 23.9, indicating good and excellent functional ability following LSS. The location of the resected tumour was associated with the MSTS score in three studies [Citation37,Citation40,Citation43]. For example, in distal femur groups, the MSTS mean scores were above 23, indicating excellent functional ability. However, the correlation was not statistically significant in two of the papers [Citation37,Citation40] and the third study did not statistically analyse this correlation [Citation43]. Two studies investigated the correlation between the type of resection, whether extra-articular (EAR) or intra-articular (IAR), and the MSTS score [Citation35,Citation39]. One study found that the MSTS score was significantly better for IAR than for EAR [Citation39], whereas the other study, which had a larger sample size [Citation35], found no significant difference in the MSTS scores between the two procedures. Not all papers had descriptive data for the results of the MSTS components; however, “walking capacity” and “use of support” were reported in three papers and scored the lowest among the MSTS components [Citation17,Citation38,Citation39]. “Emotional capacity” and “functional ability” scored the lowest in two studies [Citation20,Citation40], while coversly in the same two papers, “pain” was the highest scored component. All of the components appeared to be affected by age and demographics, but no statistical correlations were presented to assess significance.

Multiple objective measures were also used to assess outcomes. Performance tests were used to assess physical and functional outcomes (6-min walk test, timed up & go, timed up & down stairs, various walking activities, and lie down & stand up). This set of tests was used in two papers [Citation17,Citation21]. The tests conducted in van Egmond-van Dam et al. [Citation17] did not show any improvement between 2-and 7-years post-operation. Bekkering et al. [Citation21] found no correlation between the type of LSS and the results of these tests; however, they reported that the LSS group had significantly better outcomes in some of these tests in comparison with an ablative surgery group.

The Physiological Cost Index (PCI) is an objective indirect measure of oxygen cost during exercise or walking [Citation46]. It was used in two studies [Citation19,Citation21], but contradicting results were found. Malek et al. [Citation19] reported a significantly better gait speed and distance in the LSS group than in the amputation group. In contrast, no significant differences between the LSS and ablative groups were found in the study by Bekkering et al. [Citation21], who also used activity monitors in a cross-sectional study for 24 h/7 days and showed no statistically significant difference between the groups. The PCI outcome measure has therefore been reported to be a valid but unreliable tool [Citation46,Citation47], and it has not been validated for use with sarcoma patients [Citation19]. A concluding statement of this theme is the variety of outcomes measured makes comparison difficult and this population may benefit from the development of a Core Outcome Set [Citation48], especially given the clear definition of the cohort.

Quality of life

Quality of life (QoL) encompasses a wide range of interrelated aspects that impact satisfaction and well-being [Citation49]. In soft tissue and bone cancer patients in particular, QoL aspects are considered difficult to assess due to heterogenosity of the population. McDonough et al. [Citation50] reported lower Health-Related QoL of Sarcoma patients when compared to healthy individuals in physical and psychosocial domains, despite the general lower outcme measures of this population in the different disease stages, some outcomes were found specifically higher in these patients such as fatigue, insomnia, loss of appetite and social interaction.

In this review, patient-reported outcome measures were used in 6 papers to assess the QoL of participants and its correlation with impairment and disability [Citation17–21,Citation37]. The Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) was used in five out of the 12 reviewed papers [Citation17–21]. The range of scores in these studies varied widely, with the lowest being reported by Zhang et al. [Citation18] in a knee arthroplasty group (76.33%), and the highest was 93.2% in van Egmond-van Dam et al. [Citation17]. The variation in scores suggest mild to moderate disability levels, but special consideration for confounding factors as age, gender and extent of surgery were ambiguous among the studies found. Carty et al. [Citation20] was the only study to address the TESS score in detail; the study found that the most affected components were related to kneeling movements, sport activities and walking upstairs or uphill. In four studies [Citation17–21] no significant correlation was found between the TESS score and other variables, such as the type of procedure and comparison with an amputee group. However, Carty et al. [Citation20] found a moderate positive correlation between the TESS score and the MSTS sub-components of walking ability and emotional acceptance. QoL was assessed by other patient-reported outcome measures, such as the Baecke Questionnaire [Citation17,Citation21], the Short-Form 36 Questionnaire [Citation42], the Reintegration to Normal Living Index (RNL) [Citation19] and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) score [Citation37]. These outcome measures covered different perspectives of QoL ranging from physical and leisure activities, pain, wellbeing, social and emotional status from patient-perspectives which is essential in this aspect rather than relying solely on clinician-based outcomes. All of the self-reported outcome measures suggested a good-to-high QoL for LSS patients. The RNL score in Malek et al. [Citation19] was the only outcome measure to report a significantly better QoL level in LSS patients compared to an ablative surgery group, while the other studies found no significant difference between groups.

Gait and knee goniometry

There is a paucity of literature on gait in this field and it was investigated in only one study. Using a cross-sectional design, the authors conducted gait analysis with a small group of patients via convenience sampling at a university hospital and compared the findings with healthy data [Citation38]. The study itself had many limitations, including a small sample size and a wide variation in age (8 − 44 years) and corresponding MSTS scores. Singh et al. [Citation38] revealed significant differences between the affected and non-affected site in terms of knee goniometry and gait quality (determined as “pattern” and cyclicality of gait). In addition, the affected gait pattern was positively correlated with the lowest-scoring MSTS component, which was walking ability. This finding is consistent with the three papers reporting “walking ability” as having the lowest score [Citation17,Citation38,Citation39]. Interestingly, the study found that 90% of participants who exhibited stiff knee gait when the range of motion (ROM) was actively and passively assessed were within a normal range, although their gait was affected.

Range of motion of knee flexion and extension was measured in eight of the papers; however, its calculation was inconsistent. Zhang et al. [Citation43] reported the use of ROM to assess knee goniometry; however, it was used with patients who developed the complication of “patella alta”, which is a high position of the patella in the knee, and the rest of the participants were disregarded in this study. ROM has been used in multipurpose studies that are concerned with post-operative outcomes in terms of survival, complications and functional outcomes. Therefore, the ROM reported through the analysis of these papers ranged considerably, from 60 degrees to 140 degrees, which was the highest degree reported among the studies [Citation20,Citation35,Citation38–40,Citation43,Citation50]. Only four papers [Citation18,Citation20,Citation35,Citation40] addressed ROM with univariate statistical tests with either the type of procedure or location of tumour.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to gain insights into non-oncological outcomes following LSS around the knee due to osteosarcoma. The included papers were diverse in their protocols, healthcare settings, location and population. The surgical intervention of LSS itself varied from study to study due to the anatomical site, tumour characteristics, cancer stage and the indication for chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The study design and methodology of the reviewed studies also varied widely; most of the studies were retrospective and can be considered as level III, IV or V, according to Sackett [Citation51]. Moreover, the studies consisted of small sample sizes, which may lead to systematic bias.

However, due to the low occurrence of this disease clinical trials are challenging and therefore studies are limited to longitudinal and observational methods. Some of the reviewed papers had multiple aims; therefore, these studies could not provide a coherent analysis of their findings. The results showed that non-oncological recovery outcomes were not investigated and analysed to the same extent as other outcome measures, such as survival rates or surgical complications.

Functional outcomes

This review revealed the lack of studies in this field and the limited outcomes that were deemed important to measure. The Musculoskeletal Tumour Society (MSTS) scoring system is an oncology-specific subjective outcome measure that relies on the clinician to interview the patient. The MSTS score measures functional outcome with reference to six components: pain, functional ability, emotional acceptance, use of support, walking capacity and gait. Each component is assigned a score ranging from 0 (lowest) to 5 (highest), where 30 is the maximum score achievable. A score of 23–30 is considered an excellent functional score, 15–22 is good, 8–14 is fair, and below 8 is considered a poor functional score [Citation40]. Although the MSTS score has been translated and validated in many languages and is considered to be a reliable tool, it can over- or under-estimate functional levels because it is assessed by the clinician and not the patient [Citation45]. The mean scores from the reviewed papers showed good-to-excellent functional levels using MSTS. The study by Singh et al. [Citation38], showed four participants (20% of the sample) aged between 10 and 50 years had a fair MSTS score, especially for walking, pain and support components. The patients reported that limited functional levels are due to moderate pain experienced with walking, requiring them to use a cane in outdoor activities. The lowest scores for walking ability and support components are consistent with the findings of van Egmond-van Dam et al. [Citation17] and Ieguchi et al. [Citation39]. However, the pain component contradicts the results of Carty et al. [Citation20] and Tan et al. [Citation40], where the pain score was the highest of the components. Inconsistent MSTS scores can be due to confounding factors, as reported by Davis et al. [Citation52], who found the MSTS and TESS scores to be affected by tumour size, percentage of bone resected and the involvement of nervous tissue. These factors were not analysed or reported in the reviewed papers, yet some papers surmised that other factors affected the functional levels, such as the type of LSS procedure (IAR vs EAR), as was reported by four studies [Citation20,Citation35,Citation36,Citation39]. Ieguchi et al. [Citation39] was the only study that reported EAR to have reduced functional outcomes than IAR. This is consistent with the findings in related literature [Citation53,Citation54].

Age was widely heterogeneous in most of the reviewed papers; however, two studies were dedicated to paediatric and young adult patients [Citation18,Citation20] and demonstrated that some aspects of the functional levels, gait and QoL outcomes were within acceptable ranges for this subpopulation. Activity in the sport domain, as measured using the Baecke questionnaire, was lowest in [Citation21] for this subpopulation; this is consistent with the findings of related papers [Citation55–57], where sport activity was the most affected aspect in the lives of these children. This is an important finding, as activity in sport is reported as an important child occupation to support health and well-being, but also social interaction [Citation58–60].

Surgical outcomes

LSS was compared with ablative surgeries in four papers and the findings were contradictory; Shahid et al. [Citation35] and Malek et al. [Citation19] reported better functional and gait outcomes, where van Egmond-van Dam et al. [Citation17] and Bekkering et al. [Citation21] reported no differences. However, these four studies reported no differences for QoL aspects between the LSS and ablative surgery. The Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) is a valid and reliable outcome measure used to assess disability in sarcoma patients aged 12–85 years [Citation61]. TESS is a procedure-specific and self-reported questionnaire for patients following LSS. The score consists of 30 questions reporting the difficulty level of performing tasks related to dressing, grooming, mobility, work, sport and leisure. The score is calculated between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating better outcomes [Citation61].

Robert et al. [Citation62] demonstrated that the QoL did not substantially differ between the LSS and ablative surgery groups, instead they reported patients were mainly affected by the functional level and body image issues. Primary findings were supported by [Citation63–65], reporting no differences in QoL between groups. Postma et al. [Citation63] further reported that body-image was the main issue in an amputee group, whereas the LSS group experienced more physical problems, such as pain, distress and ADL.

Nagarajan et al. [Citation64] found that low levels of education (attainment rather than literacy levels) significantly affected QoL. Aksnes et al. [Citation65], a study by the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group in Norway and Sweden, found QoL to be similar; however, physical functioning was significantly better in the LSS group.

Other considerations

The findings presented here can vary based on cultural, financial and educational factors. Tan et al. [Citation40] discussed finances as an important factor in deciding the treatment protocol. Patients who were candidates for LSS with a required chemotherapy regimen, but who struggled financially, chose to undergo amputation, as they could not afford the standard treatment protocol. However, this would potentially have longer financial implications to the patient due to the life-long post-amputation rehabilitation, possible prostheses service provision and medical device supply, maintenance and repair requirements.

Jauregui et al. [Citation66] confirmed this assertion that the long-term care of amputation is slightly higher than LSS because the amputee requires life-long prosthesis maintenance, check-ups and stump care. However, this finding was positively correlated with age and the cost of the prosthesis. Therefore, the cost aspect of both procedures may vary based on demographics, the healthcare system supporting the patient, functional levels and the type of prosthesis device available.

The overall heterogeneity of the papers made the synthesis of findings difficult. This was due primarily to the resultant papers using different outcome measures and crucially, knowing what the important outcomes to measure are. In such a population, one could argue that the patients themselves could help determine what is important to measure in non-oncological recovery outcomes as it directly affects their ability to engage in meaningful occupation and improve the quality of their life. The findings presented here therefore identify and synthesise knowledge on non-oncological outcomes associated with LSS in patients with sarcoma around the knee, providing a summary of the evidence to inform clinical decision making and identify future research priorities. However, it is important to note that this is scoping review only included published academic research. It did not include a search of the grey literature, an therefore there is a risk of “publication bias” as it may not representative of all the research carried out in this field.

Conclusion

This scoping review investigated the non-oncological outcomes of LSS in patients with sarcoma around the knee. The findings were summarise into three themes: (1) functional outcomes, (2) QoL, and (3) gait and knee goniometry. The functional outcomes demonstrated good-to-excellent levels for LSS patients and the type of surgical procedure may affect the level of functionality. QoL did not substantially differ between the LSS and ablative surgery groups. However, studies did report that the aspects of QoL that patients were mainly affected by were pain, distress, reduced functional levels (in ADLs particularly) and body image issues. Gait patterns and walking ability were reported to adapt by using a flexed knee and a walking aid in outdoor activities. Most patients were affected by ROM limitations in the form of extension lag or limited flexion. While understandable, more holistic outcomes must be considered if we are to fully understand recovery following LSS from a a biopsychosocial and patient-centred perspective. This scoping review highlighted inconsistencies and confounding factors that emphasise the importance of evidence-based guidance to support and inform healthcare providers during clinical decision-making.

Author contributions

NAMD conceptualised the topic and conducted the literature search and analysis of the literature.

CO provided content from a specialist physiotherapy perspective, provided a critical review and helped refine the manuscript for publication.

MDH provided perspective from a health psychology viewpoint and provided critical review prior to submission of the manuscript.

CM provided guidance during the review process, refined and finalised the manuscript for publication.

Double blind policy

The authors have chosen to adhere to the double-blind policy therefore have removed any information which might identify the author’s identity.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would also like to acknowledge the international research consortium, Exceed Research Network (ERN), coordinated by the International Non-Government Organisation, Exceed Worldwide, based in Lisburn, Northern Ireland, for providing substantial support to MDH, CO and CM.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Wittig JC, Bickels J, Priebat D, et al. Osteosarcoma: a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(6):1123–1132.

- Taran SJ, Taran R, Malipatil NB. Pediatric osteosarcoma: an updated review. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(1):33–43.

- Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer. 2009;115(7):1531–1543.

- Valery PC, Laversanne M, Bray F. Bone cancer incidence by morphological subtype: a global assessment. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(8):1127–1139.

- Jaffe N, Bruland O, Bielack S. Pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. New York (NY): Springer; 2010.

- Shiu Manh, Hajdu SI, Fortner JG. Surgical treatment of 297 soft tissue sarcomas of the lower extremity. Ann Surg. 1975;182:597.

- Clark MA, Thomas JM. Amputation for soft-tissue sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(6):335–342.

- Carrle D, Bielack SS. Current strategies of chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Int Orthop. 2006;30(6):445–451.

- Delaney TF, Kepka L, Goldberg SI, et al. Radiation therapy for control of soft-tissue sarcomas resected with positive margins. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(5):1460–1469.

- Steinau H-U, Daigeler A, Langer S, et al. Limb salvage in malignant tumors. Semin Plast Surg. 2010;24(1):18–33.

- Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Delling G, et al. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: an analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(3):776–790.

- Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, et al. Osteosarcoma treatment - where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(4):523–532.

- Zhang Y, He Z, Li Y, et al. Selection of surgical methods in the treatment of upper tibia osteosarcoma and prognostic analysis. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40(9):528–532.

- Brigman BE, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, et al. Allografts about the knee in young patients with high-grade sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(421):232–239.

- Ek EW, Rozen WM, Ek ET, et al. Surgical options for reconstruction of the extensor mechanism of the knee after limb-sparing sarcoma surgery: an evidence-based review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(4):487–495.

- Jentzsch T, Erschbamer M, Seeli F, et al. Extensor function after medial gastrocnemius flap reconstruction of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(7):2333–2339.

- van Egmond-van Dam JC, Bekkering WP, Bramer JAM, et al. Functional outcome after surgery in patients with bone sarcoma around the knee; results from a long-term prospective study. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(8):1028–1032.

- Zhang P, Feng F, Cai Q, et al. Effects of metaphyseal bone tumor removal with preservation of the epiphysis and knee arthroplasty. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8(2):567–572.

- Malek F, Somerson JS, Mitchel S, et al. Does limb-salvage surgery offer patients better quality of life and functional capacity than amputation? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(7):2000–2006.

- Carty CP, Dickinson IC, Watts MC, et al. Impairment and disability following limb salvage procedures for bone sarcoma. Knee. 2009;16(5):405–408.

- Bekkering WP, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Koopman HM, et al. Functional ability and physical activity in children and young adults after limb-salvage or ablative surgery for lower extremity bone tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103(3):276–282.

- Fineout-Overholt E, Johnston L. Teaching EBP: asking searchable, answerable clinical questions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2005;2(3):157–160.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):48.

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294.

- Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 2nd ed. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications Inc; 2016.

- Hek G. Systematically searching and reviewing literature. Nurse Res. 2000;7(3):40–57.

- Boland A, Cherry G, Dickson R. Doing a systematic review. 2nd ed. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd; 2017.

- Bielack S, Carrle D, Casali PG. Osteosarcoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2009;20(4):137–139.

- Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide. Nurse Res. 2011;18(4):45.

- CASP Checklists - CASP - critical appraisal skills programme. 2019.

- Critical Appraisal Tools. Joanna Briggs Institute. 2020.

- Developing NICE Guidelines: Tools & resources [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources

- Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–676.

- Shahid M, Albergo N, Purvis T, et al. Management of sarcomas possibly involving the knee joint when to perform extra-articular resection of the knee joint and is it safe? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(1):175–180.

- Hardes J, Henrichs MP, Gosheger G, et al. Endoprosthetic replacement after extra-articular resection of bone and soft-tissue tumours around the knee. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(10):1425–1431.

- Puerta-GarciaSandoval P, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Trigueros-Rentero MA, et al. Mid- to long-term results of allograft-prosthesis composite reconstruction after removal of a distal femoral malignant tumor are comparable to those of the proximal tibia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2218–2225.

- Singh VA, Heng CW, Yasin NF. Gait analysis in patients with wide resection and endoprosthesis replacement around the knee. Indian J Orthop. 2018;52(1):65–72.

- Ieguchi M, Hoshi M, Aono M, et al. Knee reconstruction with endoprosthesis after extra-articular and intra-articular resection of osteosarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(9):812–817.

- Tan PX, Yong BC, Wang J, et al. Analysis of the efficacy and prognosis of limb-salvage surgery for osteosarcoma around the knee. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2012;38(12):1171–1177.

- Carty CP, Bennett MB, Dickinson IC, et al. Electromyographic assessment of Gait function following limb salvage procedures for bone sarcoma. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2010;20(3):502–507.

- Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, et al. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(286):241–246.

- Zhang C, Hu J, Zhu K, et al. Survival, complications and functional outcomes of cemented megaprostheses for high-grade osteosarcoma around the knee. Int Orthop. 2018;42(4):927–938.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2018;310:2191–2194.

- Janssen SJ, van Rein EAJ, Paulino Pereira NR, et al. The discrepancy between patient and clinician reported function in extremity bone metastases. Sarcoma. 2016;2016:1–6.

- Ijzerman MJ, Nene AV. Feasibility of the physiological cost index as an outcome measure for the assessment of energy expenditure during walking. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(12):1777–1782.

- Graham RC, Smith NM, White CM. The reliability and validity of the physiological cost index in healthy subjects while walking on 2 different tracks. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(10):2041–2046.

- Webbe J, Sinha I, Gale C. Core outcome sets. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018;103(3):163–166.

- Meeberg GA. Quality of life: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(1):32–38.

- McDonough J, Eliott J, Neuhaus S, et al. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and unmet health needs in patients with sarcoma: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):653–664.

- Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1989;95(2 Suppl):2S–4S.

- Davis AM, Sennik S, Griffin AM, et al. Predictors of functional outcomes following limb salvage surgery for lower-extremity soft tissue sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73(4):206–211.

- Kinkel S, Lehner B, Kleinhans JA, et al. Medium to long-term results after reconstruction of bone defects at the knee with tumor endoprostheses. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(2):166–169.

- Nakamura S, Kusuzaki K, Murata H, et al. Extra-articular wide tumor resection and limb reconstruction in malignant bone tumors invading the knee joint. Oncol Rep. 2001;8(2):365–368.

- Jacobs PA. Limb salvage and rotationplasty for osteosarcoma in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;(188):217–222.

- Eiser C, Cool P, Grimer RJ, et al. Quality of life in children following treatment for a malignant primary bone tumour around the knee. Sarcoma. 1997;1(1):39–45.

- Tunn P-U, Schmidt-Peter P, Pomraenke D, et al. Osteosarcoma in children: long-term functional analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;421:212.

- Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, et al. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:135.

- Ziviani J, Macdonald D, Ward H, et al. Physical activity and the occupations of children: perspectives of parents and children. J Occup Sci. 2006;13(2–3):180–187.

- Feldhacker D, Cerny S, Brockevelt B, et al. 2018. Occupations and well-being in children and youth. In: de la Vega LR, Toscano WN, editor. Handbook of leisure, physical activity, sports, recreation and quality of life. Cham: Springer. p. 119–138.

- Matthews CE, Ainsworth BE, Thompson RW, et al. Sources of variance in daily physical activity levels as measured by an accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(8):1376–1381.

- Robert RS, Ottaviani G, Huh WW, et al. Psychosocial and functional outcomes in long-term survivors of osteosarcoma: a comparison of limb-salvage surgery and amputation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(7):990–999.

- Postma A, Kingma A, De Ruiter JH, et al. Quality of life in bone tumor patients comparing limb salvage and amputation of the lower extremity. J Surg Oncol. 1992;51(1):47–51.

- Nagarajan R, Clohisy DR, Neglia JP, et al. Function and quality-of-life of survivors of pelvic and lower extremity osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(11):1858–1865.

- Aksnes LH, Bauer HCF, Jebsen NL, et al. Limb-sparing surgery preserves more function than amputation: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 118 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90–B(6):786–794.

- Jauregui JJ, Nadarajah V, Munn J, et al. Limb salvage versus amputation in conventional appendicular osteosarcoma: a systematic review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2018;9(2):232–240.