Abstract

Purpose

Reliable, valid, and pragmatic measures are essential for monitoring and evaluating employment readiness and comparing the effectiveness of alternative implementation strategies. The Work Readiness Inventory (WRI) and Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA) are valid measures of employment readiness in neurotypical populations; however, their acceptability (i.e., user perception of measure as agreeable/satisfactory) for persons on the autism spectrum is not yet known. This investigation assesses the acceptability of the WRI and a modified ACLSA (ACLSA-M) in measuring employment readiness in youth/young adults on the spectrum.

Methods

A concurrent triangulation mixed-methods study design utilizing quantitative pre-post measurement of a community-based employment readiness program alongside qualitative survey assessment was employed to determine concurrent acceptability. For robustness, further explication through peer debriefing of experts evaluated the retrospective acceptability via interview and acceptability-rate assessment.

Results

Findings indicated that both measures are acceptable, although individual- and job-specific item modifications are advised, particularly due to disability-specific needs. Significant change in employment readiness in youth/young adults on the spectrum supports concurrent acceptability. Peer debriefing provided rich data on retrospective acceptability. Acceptability-rates of 0.84 and 0.91 confirm broad acceptability of these measures.

Conclusions

Implications are presented for clinicians and researchers, highlighting the relevance for autism-specific measurement development and acceptability.

Given the lower labor force participation of persons on the autism spectrum, a combination of measures should be used in the assessment of an individual’s employment readiness.

In youth and young adults on the spectrum, employment readiness can be measured using the Work Readiness Inventory (WRI) and a modified version of the Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA-M).

In clinical practice and research, modifying the contents of these measures may be advised to minimize language complexity, and maximize ease in self report.

When designing, developing, and testing new measures in rehabilitation practice or research, the intent should be broadened by involving diverse representation from the project outset, by engaging both those on the spectrum and neurotypical populations.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

The employment rates for working-age individuals identified as having autism spectrum disorder (autism) are the lowest of any disability category in Canada, with only 21.5% of people 15–64 years of age on the spectrum engaged in the labor force [Citation1]. This low labor force participation (working or seeking work) is a trend that is seen internationally with employment rates ranging from 10% to 50% [Citation2,Citation3], despite this neurodiverse population having important skills to contribute to the workforce. The neurodiversity paradigm highlights how neurological differences are valuable and result from normal and natural variation, rather than disease or disorder, and can have desirable and enabling consequences both for the individual and society [Citation4,Citation5].

Persons on the autism spectrum (herein referred to as “the spectrum”) experience significant barriers in the workplace and education, as well as in accessing social services and supports, which may limit labor force participation [Citation6–9]. Unemployment for this group is associated with lower financial security, more limited independence, less community participation, and diminished self-esteem, often resulting in poorer quality of life and well-being [Citation10]. Employment among persons on the spectrum is linked with the broader “ecosystem” comprised of community resources, family support, workplace capacity building (e.g., employer, co-workers), and supportive policy [Citation11]. Thus, supports for employment may be limited if focused only on singular aims such as individual preparedness.

Community-based vocational resources and employment supports can improve employment success for adults on the spectrum [Citation12]; however, what predicts success appears to be a complex combination of factors, including employment readiness [Citation10,Citation13,Citation14]. Understanding employment readiness and how it intersects with other factors leading to meaningful employment is a critical step toward increasing employment outcomes for persons on the spectrum [Citation15–17]. Employment readiness encompasses an individual’s level of employment skills, core life skills (including social and self-management skills), and daily living skills that are all linked closely to an individual’s overall sense of well-being [Citation12,Citation13]. Self-development, occupational focus and action, navigation of work life, and personal well-being and health all contribute to employment readiness [Citation18].

Neurodiverse persons on the spectrum often experience challenges with social interaction and communication [Citation19–22], repetitive behaviors [Citation23], imaginative abilities [Citation5], sensory difficulties [Citation5,Citation24,Citation25], and restricted interests [Citation26]. Thus, persons on the spectrum can benefit from support that fosters the development of relevant and appropriate “soft skills” in areas like relationships and communication, work and study life, self-care, and career and life planning [Citation27]. However, a 2018 evaluation of employment support services indicated that programs appear to generally target specific work preparation tasks (such as resume writing) and not employment-related issues specific to these areas [Citation27].

The assessment of employment support program success and individual employment readiness is often based on the use of participant skill assessments developed for use with neurotypical populations. While numerous measures have been developed and validated to evaluate employment readiness and life skills, many of these, including career-planning and employment readiness measures, have not yet been assessed for use with persons on the spectrum [Citation28,Citation29]. The Work Readiness Inventory (WRI) and Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA) are two valid and reliable measures of employment readiness and life skills which were developed for use in neurotypical populations [Citation30,Citation31]. As a hallmark for a strong measure of employment readiness, it should be easy to administer, and present minimal burden on the individual completing it. The measure must also be acceptable such that users perceive it as “agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory,” considering key elements such as content, complexity, and comfort [Citation32,p.67]. Acceptability is a measure of the implementation outcome, which helps determine the quality of use of particular practices [Citation28] as well as a precondition for attaining desired service delivery outcomes [Citation32].

The WRI and a modified version of the ACLSA (ACLSA-M) were used in a community-based vocational intervention called Employment Works Canada (EWC) that was offered to youth and young adults on the spectrum. EWC is a Canada-wide employment readiness program for youth and young adults (15–29 years of age) with autism that focuses on social, communication, and job skills development [Citation33]. Using a broad-based approach, EWC characterizes work readiness within components of self-development, occupational focus and action, navigation of work life, and personal well-being and health [Citation18]. In this context, the ACLSA was modified to specifically capture life skills specific to employment readiness – social skills, well-being (including mental health), and other generalized life skills that may be required for employment of those on the spectrum. While both the ACLSA and WRI are reliable and valid measures in neurotypical populations, the acceptability is unknown among autistic youth. This study aims to answer the following question: are the WRI and ACLSA-M acceptable measures of employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum?

Methods

According to Proctor et al. [Citation32], acceptability should be assessed from participant and/or provider perspectives, considering either knowledge of or direct experience with various dimensions of the practice, or in this case, the measures, implemented. The literature supports both quantitative and qualitative methods of assessing healthcare implementation outcomes, including acceptability [Citation28,Citation34,Citation35]. Further, acceptability can be assessed prospectively (before implementation), concurrently (during implementation), and retrospectively (after implementation) [Citation35]. According to research on evaluating and measuring implementation outcomes such as acceptability, methods ought to be defined by the social purpose of the investigation [Citation34].

Participants

Concurrent acceptability

Participants were included in the quantitative assessment of concurrent acceptability when they met the following eligibility criteria:

EWC program enrolment. Enrolment criteria for EWC included a diagnosis of autism, being unemployed or underemployed, struggling to get and/or keep a job, seeking an opportunity to build workplace skills, openness to exploring different workplaces, age range of 15–29 years, and willingness to engage in a three-month manualized program for five hours per week.

Provision of informed consent (including sufficient comprehension to provide informed consent).

An age-equivalency (AE) score of at least 13 years on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-4 (PPVT-4) as administered and evaluated by EWC facilitators.

Participants were excluded when the WRI and ACLSA-M were not completed at the beginning and end of the intervention.

We randomly selected two participants from those who participated in the quantitative assessment for further qualitative assessment. These participants were identified via criterion sampling [Citation36] using the criteria that their cases indicated improved work readiness on the WRI and improved life skills indicated by the ACLSA-M domain changes. By selecting a small number of individuals with information-rich cases related to employment readiness, the phenomenon of interest, we were able to gain more detail around the nature of these changes to understand relevance to the measures [Citation36,Citation37].

Peer debriefing for retrospective acceptability

The selection of peer debriefers is a key to enhancing trust, credibility, and strength in findings. Of primary importance is the inclusion of participants who are meaningfully engaged in the fields of employment readiness and life skills assessment and are able to purposefully contribute to the validity of the findings [Citation38]. In this case, peer debriefing included assessment of retrospective acceptability of the WRI and ACLSA-M in measuring employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum, through key informant stakeholder interviews and survey assessment. Participants were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling and were selected for inclusion when identified as an expert in the area of employment readiness for youth and young adults on the spectrum. Source of expertise was determined through scholarly publications, research contributions, clinical experience, and/or other recognized and documented contributions in the areas of employment readiness, vocational training, or employment supports for youth and young adults on the spectrum. Peer debriefing participants were recruited through existing researcher networks and the Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorder Alliance (CASDA) 2018 Leadership Summit.

Setting

To understand the concurrent acceptability of these measures in practice, the WRI and ACLSA-M were used as pre-post measures for employment readiness in the EWC program. EWC is a Canada-wide employment readiness program for youth and young adults (15–29 years of age) on the spectrum that focuses on social, communication, and skill development to improve employment readiness, support occupational selection precision, and provide expansive work exposure [Citation39]. Using a broad-based approach, EWC characterizes employment readiness within components of self-development, occupational focus and action, navigation of work life, and personal well-being and health [Citation18].

In combination with mentorship-based training and workplace exposure, programming is tailored to individual goals and offers structured learning opportunity. Capacity building is targeted not only to participants, but also to employers, co-workers/peers, and the community at large. Domains of learning in weekly sessions, as outlined in a manualized curriculum, address the following topics: career exploration and goals, health and financial literacy, communication/socializing skills within the work environment, well-being and self-esteem, adaptive skills, and peer mentor/co-worker autism awareness [Citation11].

Participants were provided the WRI and the ACLSA-M at the beginning and at the end of the EWC program and were asked to complete the measures. Facilitators were available to answer questions or provide guidance for completion if needed.

Instruments

The WRI is a brief self-report that assesses employment readiness in six areas: responsibility, flexibility, skills, communication, self-view, and health and safety with 36 questions [Citation30]. Respondents rate their level of concern in these areas relative to the workplace on a five-point Likert scale, one being “not concerned” and five being “very concerned.” Scores on the WRI range from 36 to 180, with lower scores indicative of less concerns or perceived areas of strength, and higher scores indicative of increased concerns related to employment readiness. Used widely with neurotypical populations, the WRI focuses on “those personal attributes, worker traits, and coping mechanisms needed to not only land a job, but to keep that job” [Citation30,p.4]. The WRI exhibits strong content validity (complete construct-to-item fit, Fleiss’ kappa, K = 1) [Citation40] and concurrent criterion validity (mean Pearson’s r = −.21, p < 0.05) [Citation30], as well as internal consistency (median Spearman–Brown correlation coefficient r = 0.94, p < 0.001) [Citation30] and test–retest reliability (median Pearson’s r = 0.87, p < 0.001) when tested with neurotypical populations [Citation30].

The ACLSA is a strengths-based multidimensional instrument of capabilities, and assesses youth life skills in the areas of daily living, self-care, relationships and communication, housing and money management, work and study, career and education planning, and looking forward [Citation41,Citation42]. The ACLSA is widely used in the identification of developed life skills and for goal setting to acquire new skills [Citation31,Citation43,Citation44]. The ACLSA was modified (ACLSA-M) for use in the EWC program, honing in on generalized life skill abilities that are potential prerequisites to employment for those on the spectrum (and others), and skills directly relevant to the workplace. At the time of writing, the EWC program was the only program, to our knowledge, to use the ACLSA modified in this format. The skills underlying the items chosen for inclusion in the ACLSA-M include employment readiness, occupational focus and action, autism presentation (including social skills and behavior), and well-being (including mental health). The ACLSA demonstrates face, content, construct, and concurrent criterion validity as well as internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97), and test–retest reliability in neurotypical populations [Citation31,Citation45]. The modified ACLSA (ACLSA-M), however, has not been tested for validity or reliability.

Study design

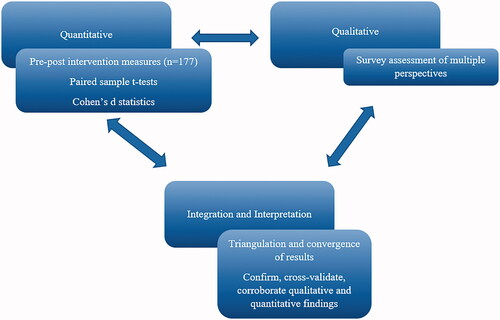

For robustness, our methodology explicitly included triangulation through quantitative and qualitative methodologies amalgamated in a complex mixed-method design selected to assess acceptability both from concurrent perspectives and retrospective perspectives. Using a concurrent triangulation mixed-methods design, we first investigated the concurrent acceptability of these measures in inferring findings about employment readiness quantitatively (using pre-post measurement) alongside qualitative data collection to elaborate on the construct of employment readiness relative to persons on the spectrum. The concurrent triangulation design is the most common and well known mixed-methods study design [Citation46], and its purpose is “to obtain different but complementary data on the same topic” [Citation47,p.122] to best understand the research problem. As represented in , the concurrent triangulation research design allows for the collection and analysis both of qualitative data and quantitative data to assess the same conceptual phenomenon simultaneously [Citation48]. While data analysis typically occurs separately, the qualitative results and quantitative results are integrated in the data interpretation stage [Citation46]. Concurrent triangulation designs are useful for attempting to confirm, cross-validate, and corroborate study findings from different methods, often adding to the depth and scope of the findings [Citation46,Citation49].

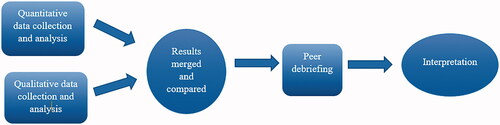

Second, to strengthen the validity of the findings, further explication through peer debriefing occurred whereby key informant stakeholders (i.e., employment readiness experts) were interviewed to evaluate the retrospective acceptability of these measures via the acceptability rate of the measures and their components by quantification of survey assessment (). Peer debriefing is often used to improve and demonstrate the rigor of qualitative research [Citation47,Citation50–53]. A well-established approach in ascertaining trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry, peer debriefing is methodologically implemented, based on the input of key experts external to the research process in eliciting their views of data resonance [Citation38]. This process further serves to “deepen understanding by collecting a variety of data on the same topic or problem with the aim of combining multiple views or perspectives and producing a stronger account rather than simply achieving consensus or corroboration” [Citation38,p.12–13].

Figure 2. Study methods consisting of a concurrent triangulation design followed by peer debriefing.

The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board (REB#15-0019, 17-2353). Secondary analysis of the anonymized program evaluation/quality improvement-oriented dataset was completed after identifying features in the data had been removed. Informed consent was received from all interview participants prior to data collection.

Data collection procedures

Concurrent acceptability

To assess concurrent acceptability of the WRI and ACLSA-M in capturing employment readiness quantitatively, participants were provided the WRI and the ACLSA-M at the beginning and at the end of the EWC program and were asked to complete the measures. Facilitators were available to answer questions or provide guidance for completion if needed. To further assess the concurrent acceptability of the WRI and ACLSA-M for use in capturing employment readiness, a review of post-EWC surveys, which contained the perspectives of the participants and their families, was conducted. These post-program surveys were provided to participants and parents and included ratings and free text. During the post-program survey, EWC participants and their parents were asked questions related to their experience in the EWC program, the phenomenon of employment readiness, and the measures utilized to capture changes in employment readiness.

Peer debriefing for retrospective acceptability

First, we utilized semi-structured one-on-one interviews to assess retrospective acceptability. Qualitative assessment was based on stakeholder knowledge of and direct experience with all dimensions of the measures to report on the perceived retrospective acceptability of the measures. Interviews occurred via telephone and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were asked to discuss the relevance, clarity, and acceptability of the measures as well as the meaning and degree to which individual items represented acceptable content, complexity, and comfort of domains.

Next, participants were also asked to rate each item on the measure as relevant in reflecting the underlying construct of employment readiness using a four-point Likert scale, from not relevant (1), somewhat relevant (2), quite relevant (3), to highly relevant (4). The item rating allowed for the quantification of participant assessment and proportion agreement on acceptability of the measure items.

In addition to the WRI and ACLSA-M, participants were also provided the full unmodified ACLSA and asked to rate each item as they had done previous. The inclusion of the full measure in the assessment of retrospective acceptability led to the determination of acceptability-rates as well as the identification of potential items on the ACLSA relevant to employment readiness for youth and young adults on the spectrum that had not been included in the ACLSA-M.

Data analysis

Concurrent acceptability

The assumption of normalcy was tested both for the WRI data and the ACLSA-M data. To evaluate the concurrent acceptability of the WRI paired sample t-tests were conducted for each domain of the WRI, using a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of 0.008 to correct for multiple comparisons. For concurrent acceptability of the ACLSA-M, paired samples t-tests were conducted for each domain using a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of 0.007 to correct for multiple comparisons. During the post-program survey, EWC participants and their parents were asked questions related to their experience in the EWC program, the phenomenon of employment readiness, and the measures utilized to capture changes in employment readiness.

Peer debriefing for retrospective acceptability

Using a six-step framework [Citation54], interview transcripts were inductively analyzed with the support of qualitative data management and analysis software (NVivo 11). This analysis framework included the following stages: step 1: become familiar with the data; step 2: generate initial codes; step 3: search for themes; step 4: review themes; step 5: define themes; and step 6: write-up [Citation54]. Data were coded line-by-line, with the interconnectedness of codes examined and salient themes extracted. Both semantic and latent themes were observed and analyzed, which allowed for recognition of the full diversity of the data.

Likert scale ratings were anonymized and pooled by item. The inter-rater proportion agreement for each item was calculated as the proportion in agreement of acceptability (those giving a rating of either 3 or 4) divided by the total number of experts according to the Lynn method [Citation55]. To address the potential inflation of values due to random chance, we linked these values to a modified kappa statistic [Citation56,Citation57]. The modified kappa was calculated for 10 participants and compared to the standards for evaluating kappa by Fleiss [Citation58] and Cicchetti and Sparrow [Citation59]. After adjusting for chance, any item with a value exceeding 0.79 was deemed acceptable. Once the inter-rater proportion agreement for each item was calculated, the measures themselves were then assessed. The measures were deemed acceptable if the proportion of items from each measure surpassed 0.80 [Citation55,Citation60].

Results

Concurrent acceptability

Between April 2017 and April 2018, a total of 177 participants took part in the EWC program in seven provinces across Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia). Participants were between 17 and 29 years of age (M = 21, SD = 3), 73% were male and 94% indicated their primary language was English. At the beginning of the program, 12% of participants were employed, and 92% indicated that they were interested in obtaining employment. Of this total, 134 participants received a PPVT AE of at least 13. Among these eligible participants, 90% (n = 121) completed the WRI and 84% (n = 112) completed the ACLSA-M at the beginning and at the end of the intervention. Data from both measures were normally distributed. There was a significant decrease in all of the WRI pre- to post-test domain scores indicating increases in employment readiness (p < 0.05) (). On the ACLSA-M, participants on the spectrum had significantly more positive scores in the domains directly related to employability: (i) relationships and communication, (ii) work and study, (iii) career and education planning, and (iv) looking forward (p < 0.05) (). Although the focus of this investigation was not on intervention effectiveness, we additionally found that Cohen’s d statistics for the WRI ranged from 0.25 to 0.28, suggestive of a small effect [Citation61]. Cohen’s d statistics on the ACLSA-M ranged from 0.29 to 0.67, suggestive of a small to medium effect [Citation61].

Table 1. Concurrent acceptability pre- and post-test scores on the Work Readiness Inventory (n = 121).

Table 2. Concurrent acceptability pre- and post-test scores on the modified Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (n = 112).

Participant 1, an 18-year-old male, had not looked for work in the four weeks preceding the program. He indicated “past unsuccessful job-finding experiences” and “no adequate training/experience” were barriers which discouraged him from actively searching for a job. Upon completion of the program, the participant’s perceptions of his communication abilities and self-view improved. On the ASCLA-M positive changes were noted in the four domains of life skills related to employment readiness: relationship and communication, work and study, career and education planning and looking forward. His parents observed positive changes in his social communication skills and mentioned:

Since doing the program, he is able to speak more confidently to people. At the end of the program, he was able to get up and speak in front of (the) group. Before [doing EWC], he would have never been able to do this. He would never speak or start a conversation, but he is now able to feel comfortable going into a bank for instance and opening an account.

Shifts in the participant’s self-view of his communication were noted on both the WRI and ACSLA-M including an increased ability to speak up for himself and perceived ability to get along with his coworkers. His parents further stated:

With EWC we are both excited and have a new outlook on his life and work. He now has the right tools and confidence he needs to get a job such as interview skills, job portfolio, and what employers expect of him.

On the WRI, the participant felt he was better able to fit in with his co-workers and be successful. At the three-month follow-up, he had obtained a general labor position at a non-profit organization. Of note, his scores appeared consistent with his reported experiences and perspectives related to employment.

The second participant, a 24-year-old female, indicated at the beginning of the program that she had looked for work during the last four weeks and would continue to look for work over the course of the program. All of her scores on the WRI improved indicating that she perceived herself as more work ready at the end of the program. At the end of the program, she indicated she was proud to accept “guidance” and “complete tasks” – items directly explored on the ACLSA-M. She indicated she “learned new skills” and indicated that she was “more prepared to find a job” and her parents stated, “I noticed her being more independent … she is ready to (take) transit to a paid job.” Shifts on the WRI Skills domain and the ACLSA-M work and study life domain reflected these sentiments. At the end of the program, she had obtained a position as a kitchen assistant in a restaurant and remained in this position at the three-month follow-up. Again, as indicated, the measure scores complemented the reported experiences of this individual with autism.

Peer debriefing for retrospective acceptability

Participants included 10 experts from across Canada who were recruited from Alberta (4), Ontario (3), Quebec (2), and Saskatchewan (1). Among participants, 30% were male, 70% female. All had extensive experience in the area of autism and employment for those on the spectrum. Forty percent had affiliation with a university, 60% were involvement in leadership roles or direct service provision with 7–30+ years of experience, and 40% had journal articles published in high caliber peer-reviewed journals.

Thematically, the qualitative data extracted were classified into three main categories, which identified areas for improvement of the two measures: (1) item-specific, (2) individual-specific, and (3) job-specific.

Item-specific

Stakeholders highlighted the relevance of the content and the clarity of item wording (i.e., complexity). They asserted that to be effectively interpreted by youth and young adults on the spectrum, many items needed nuancing and refinement. For example, an item on the ACLSA-M asks respondents to rate the following item, “I know how to use public transportation to get to where I need to go.” A participant wondered: “Are you assessing their ability to navigate using whatever means or assessing their ability to get to a workplace?” Enhancing clarity was recommended.

Items with abstract concepts or lacking specificity and/or context were also flagged as potentially problematic. It is generally more difficult for those on the spectrum to conceptualize any vagueness, and therefore may answer inaccurately. Ultimately, deconstruction of the items was a recurring theme among participants. To illustrate, a participant advised:

Dive deep a little bit more in some of the questions like ‘I can deal with anger without hurting others or damaging things’ like ‘I can recognize when I am feeling angry’ or you know ‘I know how to walk away’ or you know like breaking that down a little more.

Individual-specific

Assessment of individual characteristics like self-view and self-confidence was seen by participants to be important; however, the lack of items related to skills specific to the individual on the spectrum, such as emotional regulation, mental health, and dealing with anxiety, was raised as a concern. These skills were noted to commonly need further development among individuals on the spectrum. The lack of communication skills, social skills, and relational skills of youth and young adults on the spectrum often result in them feeling isolated, alone, or without friends. To illustrate, one participant said: “A lot of folks…if they do get the job the reason they’ll lose it is social.” Another stated the importance of context:

That social communication piece in the workplace…what topics are, you know, workplace safe to talk about, what topics, you know, are not safe to talk about in the workplace because they’re more like, hanging out with your friends topics.

To include items related to social skills, abilities and behavioral responses to new, different, and/or frustrating circumstances were seen as a positive direction in moving forward. Along these lines, a lack of assessing abilities to manage mental health was also a commonly identified need for inclusion.

Job-specific

The majority of participants noted a general need for more focus on the person-job fit, as many of the skills assessed were not necessarily needed for all jobs. One participant wondered: “There will be a lot of folks who try for jobs that they don’t need to create and save and print and send a document. Does this mean they’re not work ready?” There were participants who noted not only the importance of including more focus on the person-job fit, but also unique environmental factors such as group noise, distractions, and the management of job-specific situations.

Overall, all participants agreed that the measures were clear and readable. The content of the assessments was consistently understood. Specificity and clarity around the items being addressed, individual circumstances, and job circumstances were described as important considerations when administering these tools in employment readiness programs for persons on the spectrum. Stakeholders believed that modifications to the tools may improve their ability to meaningfully measure employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum. A common recommendation was for the items in the ACLSA-M and WRI to be more explicit. The lack of specificity in certain items resulted in a number of questions regarding the context of the item or requiring further elaboration, with participants recommending slight alterations to clarify any ambiguity resulting from broad interpretations of various items on the ACLSA-M and/or WRI. According to participants, more granularity would provide enhanced clarity concerning the tangible capacities being assessed. Examples of recommended item insertion include facets of accountability (owning up to mistakes and taking responsibility for one’s actions), job satisfaction (expectations), and personal reflection.

Calculation of acceptability rates allowed a deeper assessment of retrospective acceptability. Based on the pre-defined criteria of a value of 0.80 for measure acceptability, the ACLSA-M and WRI were judged acceptable by participants with acceptability rates of 0.84 and 0.91, respectively ( and ). At the item-level, 88.9% (32) of the WRI items, and 75.0% (33) of the ACLSA-M items were judged to be acceptable with an inter-rater proportion agreement acceptability rate for items greater than or equal to the pre-defined 0.79. While both measures were determined to be acceptable in reflecting employment readiness, participants noted individual items that were less useful ( and ). Critical examination and comparison between the ACLSA and the ACLSA-M provided a number of items reflective of employment readiness (with acceptability rates greater than or equal to 0.79) that were not included at the initial modification of the scale to the ACLSA-M ( and ).

Table 3. Acceptability rate based on inter-rater proportion agreement per item on the Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA) and modified Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA-M).

Table 4. Acceptability rate based on inter-rater proportion agreement for the Work Readiness Inventory individual items and overall measure.

Table 5. Items determined to be acceptable (with an acceptability rate >0.79) in assessing employment readiness on the Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA) that are not included on the modified Ansell–Casey Life Skills Assessment (ACLSA-M).

Discussion

This investigation presented a robust and novel assessment of acceptability of employment readiness measures with a specific disability population: youth and young adults on the autism spectrum. Using a concurrent triangulation mixed-methods study design, we determined that the WRI and ACLSA-M are acceptable measures in assessing employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum. We first assessed their concurrent acceptability in measuring employment readiness in this population during a pre-post measurement investigation, which indicated statistically significant increases in employment readiness following the EWC intervention, using both instruments. These findings were elaborated and deepened via qualitative assessment. Peer debriefing enabled us to utilize key informant stakeholders in the assessment of retrospective acceptability of the measures, while also contextualizing results and highlighting the findings. Determination of the acceptability-rate of each measure according to a predefined level of acceptance allowed for consideration of additional items for future measure, something which participants felt was needed. The use of this methodology allowed for a robust exploration of the implementation effectiveness of these measures. Mixing quantitative and qualitative research methodologies results in higher quality inferences [Citation62] and underscores the overarching purpose of the choices for this investigation.

The suggested modifications noted by stakeholders during peer debriefing to both measures would enhance acceptability rates and implementation effectiveness. While the full version of the ACLSA was determined to lack acceptability, assessment at the item-level allowed identification of additional items that should be reconsidered for inclusion on the acceptable modified version. These additional items illustrate the importance of including more comprehensive generalized life skills and appropriate “soft skills” in areas like relationships and communication, work and study life, self-care, and career and life planning in assessing employment readiness in those on the spectrum. Participants advocated for a more granular approach through slight alteration of item language and content on the WRI and ACLSA-M to address the ambiguity that arose in items that were too broad or lacked context. Further, such adjustments were advised for item-, individual-, and job-specific elements. These findings highlight the need and relevance for autism-specific measures to be developed or modified as proposed in this manuscript. These modifications speak to the specific challenges faced by this population in their quest to be “employment ready.” Recognizing that employment readiness exceeds measurement or documentation of a sole outcome measure and to improve confidence in tools assessing employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum, it is recommended that while acceptable in current formats, future modification of these measures occur to include improved social and life skills, including problem-solving, social initiation, and responsiveness. Of note, inherent limitations in empathizing and using pragmatic language consistently emerged.

A heterogeneity of needs among the neurodiverse autism population requires a variety of interventions to improve employment outcomes [Citation2,Citation16]. For youth and young adults on the spectrum, targeted support programs that include components of workplace communication have been shown to improve access to competitive employment over time [Citation63–65], while studies also consistently find that greater independence and enhanced life skills contribute to more positive employment outcomes [Citation16]. Research shows that improved social and communication skills and increased functional independence in personal care, use of public transportation, and social interaction increase access to meaningful employment [Citation16,Citation66]. These identified points were all reiterated by participants as being important to employment readiness.

Improvements in employment readiness for persons on the spectrum are critical as a step toward improving employment outcomes. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities highlights the need to eliminate barriers and to ensure greater opportunities for people with disability [Citation67]. The UN Human Rights secretariat recently highlighted an urgent need for implementing rights monitoring systems and specifically emphasized the lack of available data regarding youth on the spectrum [Citation68]. This means labor markets, education, and training opportunities should be inclusive and accessible, and we need measures to assess this in education and training opportunities. This study is a first step in examining implementation effectiveness and acceptability among autism-stakeholders for using the WRI and ACLSA-M in measuring employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum. The domains in these measures provide some helpful direction for focused training programs to better prepare these individuals for employment as well as individualizing their programs to address a participant's concerns about his or her work readiness skills. Items from either tool may be used to shape an attainable goal, actions, and strategies for a participant, in addition, items of concern provide an opportunity to explore supports and accommodations that may be helpful. Skills that are not a concern or that are of less of concern to an individual are equally important as they provide a means to recognize an individuals' strengths and/or skills. More broadly, these tools may be of assistance to pre-employment and employment programs as they develop their program content and objectives. These tools focus on skills that are important to employers, such as responsibility, flexibility, communication, but also address important individual attributes like self-efficacy and hopefulness that extend beyond immediate employment to career planning.

This study is not without limitations. First, the number of participants in the qualitative assessment of concurrent acceptability is a potential limitation. Next, the subjective nature of peer debriefer feedback may have introduced potential bias. Efforts were made to minimize bias by purposely recruiting participants with a variety of experience across Canada. The use of the Lynn method for proportion agreement has been criticized for its inability to adjust for chance agreement [Citation57,Citation69]. To address this concern, this study incorporated the use of the modified kappa to adjust for chance agreement and provide information about the degree of agreement beyond chance [Citation56,Citation57]. In addition, although this assessment of acceptability of the WRI and ACLSA-M in youth and young adults on the spectrum shows promise, further research is needed to examine the validity and reliability of the ASLSA-M. While the WRI and ACLSA are both valid and reliable, and the findings of this study suggest that the ACLSA-M is acceptable, research is needed to determine its psychometric properties. Lastly, further robust research is needed to replicate and generalize these findings.

Moving forward, the establishment of other tests and tools as a measure of employment readiness and life skills in persons on the spectrum is necessary to better encapsulate the space with which employment readiness nurtures improvement of employment outcomes for those on the spectrum. The WRI and ACLSA-M, at this time, serve as acceptable measures of employment readiness in this population, and their use in intervention and evaluation should not be overlooked. In addition, our use of peer-debriefing revealed that diverse stakeholders across Canada in the area of employment readiness for youth and young adults on the autism spectrum agreed on the WRI and ACLSA-M being agreeable, palatable, and satisfactory overall, with some suggested changes to content and reduced complexity to maximize self-report comfort. By making additional adjustments to these measures when used with youth and young adults on the spectrum, the WRI and ACLSA-M will arguably comprehensively measure employment readiness outcomes.

Pragmatic measures for youth on the spectrum are essential for monitoring and evaluating their success in alternative population and implementation contexts. Our findings align with others in the need for sensitivity in evaluative instrumentation for youth on the spectrum [Citation70,Citation71] and highlight the importance of clinical utility and implementation effectiveness when measuring employment support program outcomes. These findings can be utilized and applied to other employment support programs using these measures, with or without refinement, to assess employment readiness in youth and young adults on the spectrum.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge participants as well as staff, facilitators, and participants of EWC Calgary and Edmonton.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zwicker J, Zaresani A, Emery JCH. Describing heterogeneity of unmet needs among adults with a developmental disability: an examination of the 2012 Canadian Survey on Disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;65:1–11.

- Hendricks D. Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorders: challenges and strategies for success. J Vocat Rehabil. 2010;32(2):125–134.

- Shattuck PT, Narendorf SC, Cooper B, et al. Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1042–1049.

- den Houting J. Neurodiversity: an insider's perspective. Autism. 2019;23(2):271–273.

- Jaarsma P, Welin S. Autism as a natural human variation: reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement. Health Care Anal. 2012;20(1):20–30.

- Ministers Responsible for Social Services. In Unison: a Canadian approach to disability issues: a vision paper by the federal/provincial/territorial ministers responsible for social services; [Internet]; 1998. Available from: https://www.crwdp.ca/sites/default/files/ResearchandPublications/EnviornmentalScan/5.InUnison/1.InUnison-ACanadianApproachtoDisabilityIssues-Compressed.pdf

- Bizier C, Fawcett G, Gilbert S, et al. Developmental disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years and older, 2012. Can Surv Disabil. 2015;89–654(3251):8300.

- Till M, Leonard T, Yeung S, et al. A profile of the labour market experiences of adults with disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years and older, 2012; [Internet]; 2015 [cited 2020 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2015005-eng.htm

- Scott M, Milbourn B, Falkmer M, et al. Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Autism. 2019;23(4):869–901.

- Dudley C, Nicholas DB, Zwicker JD. What do we know about improving employment outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder? Sch Public Policy Publ. 2015;8(4):1–4.

- Nicholas DB, Mitchell W, Dudley C, et al. An ecosystem approach to employment and autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(1):264–275.

- Nicholas DB, Attridge M, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Vocational support approaches in autism spectrum disorder: a synthesis review of the literature. Autism. 2015;19(2):235–245.

- Walsh L, Lydon S, Healy O. Employment and vocational skills among individuals with autism spectrum disorder: predictors, impact, and interventions. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;1(4):266–275.

- Wehman P, Brooke V, Brooke AM, et al. Employment for adults with autism spectrum disorders: a retrospective review of a customized employment approach. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;53–54:61–72.

- Carter EW, Austin D, Trainor AA. Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2012;23(1):50–63.

- Pillay Y, Brownlow C. Predictors of successful employment outcomes for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic literature review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;4(1):1–11.

- Test DW, Mazzotti VL, Mustian AL, et al. Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Dev Except Individ. 2009;32(3):160–181.

- Nicholas DB, Clarke M, Mitchell W. EmploymentWorks Canada: an employment readiness program for young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Calgary (Alberta): The Ability Hub; 2015.

- Higgins KK, Koch LC, Boughfman EM, et al. School-to-work transition and Asperger syndrome. Work. 2008;31(3):291–298.

- Kuenssberg R, Murray AL, Booth T, et al. Structural validation of the abridged Autism Spectrum Quotient-Short Form in a clinical sample of people with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18(2):69–75.

- Schaller J, Yang NK. Competitive employment for people with autism. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2005;49(1):4–16.

- Sun X, Allison C, Auyeung B, et al. Validation of existing diagnosis of autism in mainland China using standardised diagnostic instruments. Autism. 2015;19(8):1010–1017.

- Militerni R, Bravaccio C, Falco C, et al. Repetitive behaviors in autistic disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(5):210–218.

- Ghilain CS, Parlade MV, McBee MT, et al. Validation of the Pictorial Infant Communication Scale for preschool-aged children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2017;21(2):203–216.

- Holwerda A, Van Der Klink JJL, Groothoff JW, et al. Predictors for work participation in individuals with an autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(3):333–352.

- Spiker MA, Lin CE, Van Dyke M, et al. Restricted interests and anxiety in children with autism. Autism. 2012;16(3):306–320.

- Nicholas DB, Zwaigenbaum L, Zwicker J, et al. Evaluation of employment-support services for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2018;22(6):693–702.

- Willmeroth T, Wesselborg B, Kuske S. Implementation outcomes and indicators as a new challenge in health services research: a systematic scoping review. Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019861257.

- Murray N, Hatfield M, Falkmer M, et al. Evaluation of career planning tools for use with individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;23:188–202.

- Brady RP. Work Readiness Inventory – administrator’s guide. Indianapolis (IN): JIST Publishing; 2010.

- Nollan KA, Wolf M, Ansell D, et al. Ready or not: assessing youths' preparedness for independent living. Child Welfare. 2000;79(2):159–176.

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

- Worktopia. What is Worktopia? [Internet]; 2018 [cited 2020 Jun 29]. Available from: https://worktopia.ca/

- Long KM, McDermott F, Meadows GN. Being pragmatic about healthcare complexity: our experiences applying complexity theory and pragmatism to health services research. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):1–9.

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–13.

- Patton MQuM. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2002.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544.

- Given LM, editor. Peer debriefing. In: The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2008.

- The Sinneave Family Foundation. Employment works; [Internet]; 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 29]. Available from: https://employment-works.ca/

- Houser R. Counseling and educational research: evaluation and application. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2009.

- Nollan KA, Horn M, Downs A, et al. Ansell–Casey Life SKills Assessment (ACLSA) and life skills guidebook manual. Seattle (WA): Casey Family Programs; 2002.

- Ansell D, Morse J, Nollan KA, et al. Life skills guidebook. Seattle (WA): Casey Family Programs; 2004.

- Horn MT. Investigating the construct validity of a life-skills assessment instrument [dissertation]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; 2001.

- Lou C, Anthony EK, Stone S, et al. Assessing child and youth well-being: implications for child welfare practice. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2008;5(1–2):91–133.

- Children, Youth and FA-R (CYFAR). Career planning; [Internet]; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 13]. Available from: https://cyfar.org/sites/default/files/CareerPlanning(ages16andup).pdf

- Hanson WE, Plano Clark VL, Petska KS, et al. Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):224–235.

- Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Pract. 2000;39(3):124–130.

- Greene J, McClintock C. Triangulation in evaluation: design and analysis issues. Eval Rev. 1985;9(5):523–545.

- Schoonenboom J, Johnson RB. How to construct a mixed methods research design. Kolner Z Soz Sozpsychol. 2017;69(Suppl. 2):107–131.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 1994.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (CA): SAGE Publications; 1985.

- Merriam SB. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1998.

- Weiss RS. Learning from strangers: the art and method of qualitative interview studies. New York (NY): Free Press; 1994.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Qualitative research in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382–386.

- Banerjee M, Capozzoli M, McSweeney L, et al. Beyond kappa: a review of interrater agreement measures. Can J Stat. 1999;27(1):3–23.

- Halek M, Holle D, Bartholomeyczik S. Development and evaluation of the content validity, practicability and feasibility of the innovative dementia-oriented assessment system for challenging behaviour in residents with dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):554.

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1981.

- Cicchetti D, Sparrow S. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am J Ment Defic. 1981;86(2):127–137.

- Davis LL. Instrument review: getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl Nurs Res. 1992;5(4):194–197.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research; Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2003.

- Wehman P, Schall C, McDonough J, et al. Project SEARCH for youth with autism spectrum disorders: increasing competitive employment on transition from high school. J Posit Behav Interv. 2013;15(3):144–155.

- Wehman PH, Schall CM, McDonough J, et al. Competitive employment for youth with autism spectrum disorders: early results from a randomized clinical trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(3):487–500.

- Taylor JL, Mailick MR. A longitudinal examination of 10-year change in vocational and educational activities for adults with autism spectrum disorders. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(3):699–708.

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(5):566–574.

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities; [Internet]; 2008. Available from: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf.

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities; [Internet]; 2017. Available from: http://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2FPPRiCAqhKb7yhshFUYvCoX405cFaiGbrIbL87R7e4hNB%2FgZKnTAU8BqK7FKCyFSQGUzS4dKwSRSD%2FCPUoSzW7oP9OI5lweGr%2Br%2B7wpRzQbCN1rv%2B%2BwMd4F0fZ

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–467.

- Chen J, Sung C, Pi S. Vocational rehabilitation service patterns and outcomes for individuals with autism of different ages. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(9):3015–3029.

- Nicholas DB, Mitchell W, Zulla R, et al. A review of CommunityWorks Canada®: toward employability among high school-age youth with autism spectrum disorder. Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19885542.