Abstract

Purpose

To present the process used to develop the low back pain (LBP) assessment tool including evaluation of the initial content validity of the tool.

Methods

The development process comprised the elements: definition of construct and content, literature search, item generation, needs assessment, piloting, adaptations, design, and technical production. The LBP assessment tool was developed to assess the construct “functioning and disability” as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Involvement of patients and health professionals was essential.

Results

The elements were collapsed into five steps. In total, 18 patients and 12 health professionals contributed to the content and the design of the tool. The LBP assessment tool covered all ICF components shared among 63 ICF categories.

Conclusions

This study presents the process used to develop the LBP assessment tool, which is the first tool to address all ICF components and integrate biopsychosocial perspectives provided by patients and health professionals in the same tool. Initial evaluation of content validity showed adequate reflection of the construct “functioning and disability”. Further work on the way will evaluate comprehensiveness, acceptability, and degree of implementation of the LBP assessment tool to strengthen its use for clinical practice.

A biopsychosocial and patients-centred approach is a strong foundation for identifying the many relevant aspects related to low back pain (LBP).

Responding to a lack of tools to support a biopsychosocial and patients-centred approach the LBP assessment tool was developed using a robust, multi-step process with involvement of patients and health professionals.

The LBP assessment tool is a strong candidate for a user-friendly tool to facilitate use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in routine clinical practice.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability and evidence strongly supports the use of a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach [Citation1–3]. The biopsychosocial and patient-centre approaches are both rooted in a holistic perspective and emphasise the importance of active involvement of patients in their own care [Citation4]. However, implementation of this approach into clinical practice is lacking [Citation5,Citation6].

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a framework and classification system for describing the biopsychosocial approach [Citation7]. To make the ICF applicable for clinical practice, ICF core sets have been developed, also for LBP [Citation8,Citation9].

Patient-centred care aims to empower patients to participate actively in their care and is a core domain of high quality healthcare [Citation10,Citation11]. The use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is considered a prerequisite for patient-centred care [Citation12–14]. PROs are commonly used as outcome measures [Citation15], but increased attention has been focused on using PROs as part of the assessment in daily clinical practice for individual patient care [Citation16–18]. A study showed that commonly used LBP-specific PROs lack items identified as important to patients with LBP [Citation19]. In addition, the items from these PROs assess pain interference and activity limitations with limited coverage of functioning and disability as conceptualised by the ICF [Citation20–22]. Therefore, development of new PROs with the involvement of patients and based on the ICF model and taxonomy is warranted [Citation19,Citation21,Citation23].

To target all facets of LBP and fully understand patient needs, a systematic and comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment is needed to obtain information from patients by use of PROs in addition to clinician-reported outcomes (ClinROs) [Citation19,Citation24]. However, an assessment tool covering functioning as a whole has not yet been developed for patients with LBP [Citation20].

Therefore, we developed the LBP assessment tool, which was based on ICF core sets [Citation9,Citation25]. The LBP assessment tool was designed to support a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach to get a more complete picture of the patient than when using the traditional biomedical approach. The tool was web-based and built from three features: a PRO instrument (PRO-LBP), a ClinRO instrument (ClinRO-LBP), and a graphical overview displaying the individual patient's functioning and disability (patient-profile-LBP). The PRO-LBP obtained information from patients regarding functioning and disability as well as contextual factors. The ClinRO-LBP was designed to standardised health professionals' clinical examination of the patient's impairment in body functions and body structures. The patient-profile-LBP integrated data from the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP and displayed the patient's functioning and disability in accordance with ICF components.

Due to the large volume of information, reporting of the LBP assessment tool was split into two papers. The aim of this first paper (part 1) was to present the process used to develop the LBP assessment tool and evaluate the initial content validity of the tool. The second paper (part 2) presents results from a field-test conducted in a real-world setting in which the LBP assessment tool was intended to be used [Citation26].

Materials and methods

Population and setting

The LBP assessment tool was developed for patients with LBP with or without leg pain. The included patients aged 18–60 years and were referred from a general practitioner to a multidisciplinary team (doctor, chiropractor, physiotherapist, and nurse) specialised in assessment at a spine centre. The spine centre is a tax-financed hospital receiving approximately 12 000 patients with LBP annually.

Development of the LBP assessment tool

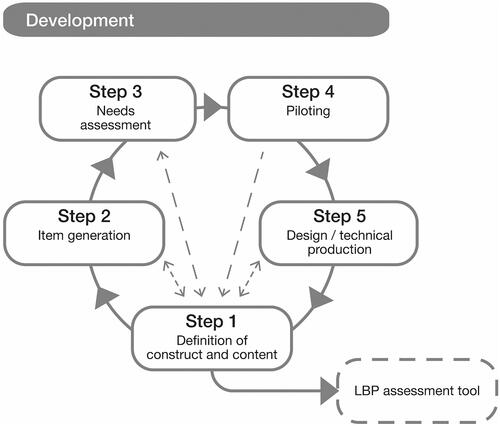

Evidence prompted seven elements to be addressed in the development of the LBP assessment tool [Citation27–29] ().

Figure 1. The seven elements addressed in the development process. Element derived from ade Vet et al. [Citation28]; bElwyn et al. [Citation27]; cRothrock et al. [Citation29].

![Figure 1. The seven elements addressed in the development process. Element derived from ade Vet et al. [Citation28]; bElwyn et al. [Citation27]; cRothrock et al. [Citation29].](/cms/asset/8c1e41dd-1256-46cc-996d-8b8026b1d9b0/idre_a_1913648_f0001_b.jpg)

Involvement of patients in the development of the PRO-LBP and health professionals in the development of the PRO-LBP, ClinRO-LBP, and patient-profile-LBP were essential. A project group comprising the authors CI, TM, and BSC was responsible for final decisions. Adaptations were integrated continuously during the development.

Definition of construct and content

The LBP assessment tool was developed to cover the multidimensional construct “functioning and disability” as defined by ICF [Citation7]. According to ICF functioning and disability are considered as a dynamic interaction between a person's health condition and contextual factors (environmental and personal factors). Environmental factors make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environment where people live and lead their lives. Personal factors are related to the background of an individual's life such as age, gender, other health conditions, and lifestyle. The components body functions, body structures, activities, and participation and environmental factors comprise various domains, and each domain contains numerous ICF categories. Personal factors are not classified [Citation7]. As the construct “functioning and disability” is the result of the presented items, the LBP assessment tool was based on a formative measurement model [Citation30]. The formative model applies to multidimensional tools where no inter-correlation between the items is expected and where a change in the construct does not necessarily affect all items [Citation31]. As the LBP assessment tool follows a formative model, the traditional psychometric approach was not appropriate in the development process [Citation30].

The content of the LBP assessment tool was based on the comprehensive ICF core set for LBP [Citation9] and the ICF rehabilitation set [Citation25] (Supplementary table S1). The rehabilitation set is endorsed in addition to condition-specific core sets when assessing functioning and disability in clinical populations [Citation25]. In total, the two core sets contain 81 unique ICF categories. The project group allocated ICF categories to the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP. The allocation was decided on the basis on which ICF categories were relevant for patients and health professionals, respectively. Continuous feedback from patients and health professionals prompted inclusion or exclusion of ICF categories.

Literature search

To clearly define the construct, explore the content validity, and inform the development process a literature search was conducted focusing on the two core sets [Citation9,Citation25] and commonly used LBP-specific PRO instruments. Literature was searched in SCOPUS and MEDLINE databases (Supplementary table S2).

Item generation

Wording of ICF categories allocated to the PRO-LBP was based on several sources: the definition of the ICF category, lay language, and terminology from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) [Citation32,Citation33]. PROMIS items are developed and validated with state-of-the-science methods to be psychometrically sound [Citation33]. Relevant response options from the PROMIS physical function item bank were applied [Citation34]. Wording of ICF categories allocated to the ClinRO-LBP was based on the definition of the ICF category [Citation7,Citation35], medical terms familiar to health professionals and commonly used in clinical practice. The project group developed an initial proposal of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP. Three patients were invited to a pre-testing of the initial PRO-LBP. Each patient answered the initial PRO-LBP, while the first author CI asked a series of probe questions about comprehension, wording, degree of difficulty and severe flaws and deficiencies [Citation36]. Three health professionals were invited to a pre-testing of the initial ClinRO-LBP using the same procedure as for the PRO-LBP. Notes from the probe questions were collected and used to adjust the initial PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP. Furthermore, feedback from the patients was used to qualify the interview guide for the focus group interviews (described below).

Needs assessment

The needs assessment consisted of focus group interviews with patients and then with health professionals. The focus group interviews were conducted to encourage discussions and sharing of experiences on how to describe functioning and disability. In total, 11 patients and eight health professionals accepted to participate. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide. Examples of key questions in the interviews with patients included: "Which information about you and your symptoms do you find important to be available for the health professional before the consultation?" and "What would you emphasise as important in a patient-centred consultation with the use of PROs?" [Citation37]. Examples of key questions in the interviews with health professionals included: "Describe how you assess functioning and disability in patients with LBP" and "How do you use PRO data in everyday clinical practice?". The interviews lasted 120 min, were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed in a four-step analysis guided by interpretive description methodology [Citation37,Citation38]. First, a thorough reading of the transcribed data was performed, followed by discussions and agreement upon themes. Second, manual coding according to the themes was carried out. Third, the themes were condensed. Finally, critical interpretation and synthesis were conducted. Results from the focus group interviews were part of the initial evaluation of content validity; the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP were adapted according to the results.

Piloting

To evaluate aspects of content validity including comprehensibility, relevance, and comprehensiveness [Citation39] of the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP, piloting was conducted [Citation40]. Thirteen patients were invited to pilot the PRO-LBP. A link to the PRO-LBP was e-mailed and a semi-structured telephone interview was then performed to explore the patients' perspectives on comprehensibility, relevance, and comprehensiveness. Five health professionals were invited to complete the ClinRO-LBP based on a patient case, followed by a questionnaire on comprehensibility, relevance, and comprehensiveness.

Design and technical production

Electronic versions of the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP were designed in collaboration between four health professionals, the first author CI and a data manager with analytical and technical expertise. Simultaneously, the patient-profile-LBP was developed. It was designed to be user-friendly and easy to interpret; colours and figures were preferred rather than numbers and sum scores. Issues concerning technical considerations, such as platforms, site structure, navigation, graphic illustrations, and data security, were discussed in the project group. The PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP were designed in SurveyXact®. The patient-profile-LBP was developed in the statistical analysis program R using Shiny Server as the web-based platform, retrieving data from SurveyXact®.

Ethics

The Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics were notified about the study (file. no. 150/2016). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (file no. 1-16-02-477-16), and a non-commercial research licence from World Health Organization was granted (LC/20/010). Written consent was obtained from patients and health professionals.

Results

The seven elements derived from evidence [Citation27–29] were collapsed into five steps ().

The element “literature search” was incorporated into “definition of construct and content” (step 1) because the evidence was fundamental to defining the construct and content. The element “adaptation” was continuously integrated; thus, adaptations were made between each step. The development of the LBP assessment tool lasted 11 months. In total, 18 patients were involved in steps 2, 3 and 4, and 12 different health professionals were involved in steps 2, 3, 4, and 5. Between steps 3 and 4, an advisory group was established consisting of two physiotherapists, two nurses, and the first author CI.

Step 1: definition of construct and content

The literature searches on ICF core sets resulted in 22 studies (Supplementary table S3). Overall, the studies supported good content validity of the LBP core set. It was found to be usable in clinical practice, capture the problems of patients with LBP and broaden the perspective of participation and environmental factors. No studies had tested the rehabilitation set in clinical practice [Citation25]. One study reported operational items and response options for the LBP core set; however, items regarding environmental and personal factors were not included [Citation41].

The literature searches on measurement properties of LBP-specific PRO instruments yielded 21 reviews (Supplementary table S4). The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) were the most frequently evaluated PRO instruments. However, their structural validity was reported to be problematic, and their content validity is understudied [Citation42].

The literature searches on content classification of commonly used LBP-specific PRO instruments according to the ICF yielded seven studies (Supplementary table S5). Key results showed that (1) few instruments addressed environmental and personal factors, (2) the LBP core set can be used as a starting point, and (3) due to reduced coverage of ICF it is not endorsed to use them.

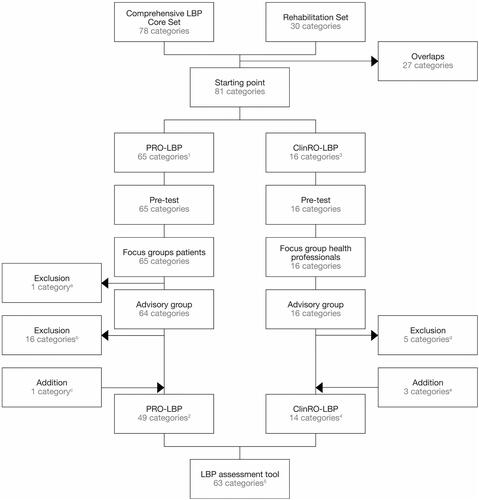

The content specification () resulted in 65 of the 81 unique ICF categories being allocated to the PRO-LBP.

Figure 3. Addition and exclusion of ICF categories during the development process. aPRO-LBP exclusion: d465. be120, e150, e225, e255, e325, e330, e360, e425, e455, e460, e465, e540, e550, e575, e585, and e590. cPRO-LBP addition: b525. dClinRO-LBP exclusion: b260, b715, b720, b735, and s770. eClinRO-LBP addition: b265, b280, and b789. 1Initial PRO-LBP: 8 categories from body functions (BF), 32 from activities and participation (AP), and 25 from environmental factors (EF). 2PRO-LBP: 9 categories from BF, 31 from AP, and 9 from EF. 3Initial ClinRO-LBP: 11 categories from BF and 5 from body structures (BS). 4ClinRO-LBP: 10 categories from BF and 4 from BS. 5LBP assessment tool: 18 categories from BF, 4 from BS, 32 from AP, and 9 from EF.

Focus groups with patients (step 3) resulted in exclusion of Moving around using equipment, as it was found “not relevant for the target population”. The advisory group recommended to reduce the number of ICF categories regarding environmental factors (25 ICF categories) and to exclude Legal services, systems, and policies. To comply with these recommendations, we used ICF categories from the brief ICF core set for LBP (10 ICF categories) to describe environmental factors and excluded the aforementioned category [Citation9]. The advisory group recommended to address bowel incontinence, a possible neurological deficit (red flag) in patients with LBP. Consequently, Defecation functions were added. Sixteen of the unique 81 ICF categories were allocated to the ClinRO-LBP. Five categories were excluded because they were “not relevant in a hospital setting”. The advisory group added three categories, namely, Touch function, Sensation of pain, and Movement functions other specified and unspecified because they were relevant from a health professional perspective. The LBP assessment tool finally comprised 63 ICF categories.

Step 2: item generation

Items in the PRO-LBP primarily comprised two types of PROMIS wording with the corresponding five-point response option (Supplementary table S6). Wording of items in the ClinRO-LBP was kept short and simple with two different response options (Supplementary table S7). Two males and one female (mean age of 49 years) participated in the pre-testing of the initial PRO-LBP. The three main findings were as follows: (1) items were comprehensible, (2) items were relevant, and (3) an introductory section was necessary to explain the aim of the PRO-LBP. One medical doctor, one physiotherapist, and one chiropractor participated in the pre-testing of the initial ClinRO-LBP. The main findings led to adaptations regarding wording of items in the ClinRO-LBP.

Step 3: needs assessment

Seven patients participated in two focus group interviews (reported elsewhere) [Citation37]. The primary findings were as follows: items should be kept to a minimum, overlapping items should be avoided, individualised answers are needed, and the PROs should be used actively in the dialogue between the patient and the health professional. The project group ensured no overlapping items and incorporated a text box to allow patients to write self-identified concerns. To facilitate use of PRO data, the patient-profile-LBP was designed. Overall, patients found that the content of the PRO-LBP covered the most important elements of functioning and disability. The patients decided that a seven-day recall period was appropriate for the PRO-LBP.

Eight health professionals participated in the focus group interview. They represented the multidisciplinary team (two chiropractors, two medical doctors, two physiotherapists, and two nurses). Three main themes emerged: diversity in clinical practice; comprehensive assessment of functioning and reduced use of PROs during the consultation. Diversity in clinical practice was related to discrepancy mainly caused by different professional backgrounds. Comprehensive assessment of functioning indicated that health professionals found assessment of functioning challenging and complex. Thus, they expressed an assessment performed in collaboration between different health professionals could be profitable. Reduced use of PROs indicated that health professionals found PRO data difficult to interpret and they were sceptical about the clinical relevance and meaning; thus, their use varied. As a result, the advisory group was established to allow more time to discuss the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP and to consider how to facilitate the use of PROs and the LBP assessment tool in routine clinical practice.

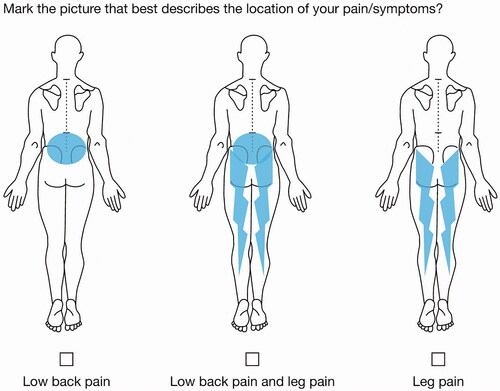

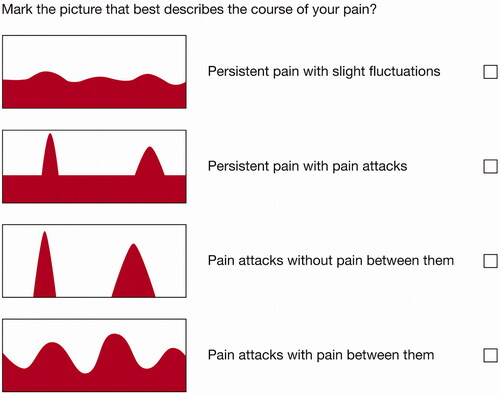

The advisory group met four times for two hours. They found that including items regarding “pain location” and “pain course pattern” in the PRO-LBP was important. Consequently, an entry question regarding “pain location” () and an item derived from the painDETECT questionnaire were added to address pain course patterns () [Citation43]. In accordance with the patients, the advisory group found a seven-day recall period appropriate.

Discussions in the advisory group resulted in three ClinRO-LBP adaptations: (1) exclusion of five categories (), (2) generation of items related to three ICF categories (), and (3) health professionals should only register positive findings to reduce the registration burden.

Step 4: piloting

Four males and four females with a mean age of 55 years completed the PRO-LBP and participated in the following telephone interview. Mean completion time of the PRO-LBP was 27 min (range: 15–40 min). Overall, the patients found that the PRO-LBP was easy to complete with relevant and meaningful items. The patients were especially satisfied with the text box allowing for the possibility to elaborate on their functioning and disability. Piloting of the PRO-LBP resulted in clarifications of items.

Two physiotherapists, two doctors, and one chiropractor with extensive experienced to assess and manage patients with LBP participated in the ClinRO-LBP piloting. Mean completion time of the ClinRO-LBP was 5 min (range: 3–12). The piloting resulted in three adaptations. First, the items were reorganised to make them more applicable to routine clinical practice. Second, clarifications regarding wordings were made. Finally, a summary section was incorporated to recapitulate the impact of the findings from the clinical examination (Supplementary table S7).

Step 5: design and technical production

This step revealed that developing a web-based tool is a complex and time-consuming process requiring several iterative steps. Furthermore, the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP were designed iteratively with the patient-profile-LBP, as adaptations in one would lead to changes in the other. Finally, in-depth knowledge about encryption, authentication and logging is essential when developing a web-based tool. Step 5 resulted in a prototype of the LBP assessment tool.

LBP assessment tool

The LBP assessment tool covered all ICF components shared among 63 categories. The PRO-LBP covered 49 ICF categories shared among 16 ICF domains from the following components: body function, activities, and participation as well as environmental factors (Supplementary table S6). Items regarding age, gender, other health conditions, and lifestyle were represented with the hitherto undeveloped ICF component Personal Factors. The items were organised in 15 sections, and the total number of items varied from 77 to 92 (). The ClinRO-LBP covered 14 ICF categories shared among five ICF domains from the body functions and the body structures components and reflected in 50 items (). The items were organised in six sections (Supplementary table S7).

Table 1. Sections in the PRO-LBP with the corresponding ICF domain and number of items.

Table 2. Sections in the ClinRO-LBP with the corresponding ICF domain and number of items.

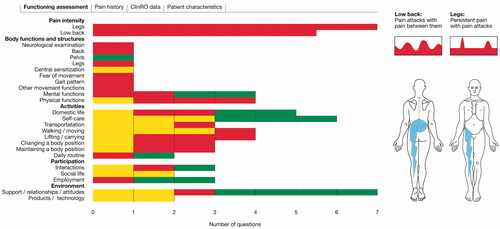

The patient-profile-LBP displayed a graphic overview of the patient's functioning and disability (). Four headers are presented at the top.

Figure 6. Screenshot of the patient profile-LBP. The colour codes signal the severity of disability: red: severe disability (response options 4 and 5); yellow: mild disability (response options 2 and 3); green: no disability (response option 1).

The header “Functioning assessment” integrated data from the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP in accordance with ICF domains together with colour-coded bars. The bars were designed to be interactive; when tapping the bar, the underlying items and responses were shown on the screen. The header “Pain history” contained information on the patient's pain: onset, character, location, duration, soothing factors, with or without leg pain symptoms, and use of pain-relieving drugs. The header “ClinRO data” comprised a detailed collection of items and responses from the ClinRO-LBP. The header “Patient characteristics” comprised baseline characteristics such as height, weight, body mass index, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, former back surgery, comorbidity, ODI scores [Citation44], and the European quality of life score [Citation45]. Furthermore, the patient's pain pattern and pain location were presented. The patient-profile-LBP also displayed the patients' self-identified concerns from the text box in the PRO-LBP.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the systematic and comprehensive development of the LBP assessment tool. A tool based on ICF core sets [Citation9,Citation25] designed to assess the multidimensional construct “functioning and disability” and support health professionals to apply a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach to assessment of patients with LBP. The initial evaluation of content validity showed that the LBP assessment tool adequately reflected the construct “functioning and disability”. To the authors knowledge, the LBP assessment tool is the first tool to address all ICF components and integrate biopsychosocial perspectives from patients and health professionals to be used in routine assessment of patients with LBP.

Step 1: definition of construct and content

To include recently published relevant literature, the literature searches were updated. Neither the search on core set [Citation41,Citation46–51] nor the search on LBP-specific PRO instruments provided new knowledge [Citation52–55]. This study is the first to provide an ICF-based tool for patients with LBP addressing ICF categories from all ICF components. Previous studies [Citation41,Citation47] presented a checklist based on the ICF core set for LBP [Citation9] to facilitate patient ratings of activity limitations and participation, but did not include environmental or personal factors [Citation35,Citation42]. We included contextual factors (environmental and personal factors) in the PRO-LBP, which is in accordance with findings from a recent study [Citation19]. They concluded that commonly used LBP specific PRO instruments do not evaluate contextual factors, though they are very important to patients [Citation19].

Step 2: item generation

To determine if items from the PROMIS physical function item bank could have been integrated into the PRO-LBP, the authors TM and CI linked the items to the ICF [Citation56]. However, the PROMIS-items did not cover all ICF components, and several items addressed more than one ICF category. Thus, we did not directly apply the items, but still used PROMIS wordings [Citation34] in combination with the ICF categories [Citation7,Citation35]. To develop operational items for the core sets, we used a self-development approach. Two other approaches have been suggested: (1) use of the generic ICF qualifiers and (2) integration of items from previous PRO instruments [Citation57]. We did not use the ICF qualifiers as their reliability [Citation58] and validity were unclear when we planned the study [Citation59]. However, professionally rated ICF qualifiers have been recently used to measure functioning [Citation60]. Consequently, we could have used the qualifiers for the ClinRO-LBP, but their applicability for patient ratings remains unclear. We did not use items from commonly used PRO instruments due to reduced validity and coverage of the ICF components [Citation22,Citation54]. Moreover, the self-development approach has shown to generate more validated items than using items from previous PRO instruments [Citation48]. Our study contributes with new knowledge on the development of operational and user-friendly items for ICF core sets to advance implementation of core sets in clinical practice.

Step 3: needs assessment

The perspectives of patients and health professionals led to inclusion and exclusion of ICF categories in the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP (). Patients suggested to “keep the number of items at a minimum”, which were a challenge when using the comprehensive LBP core set (78 categories). We considered using the brief core set as a starting point (35 categories); however, it did not provide sufficient information about pulling/pushing and leisure/recreational activities [Citation61]. Thus, we used the comprehensive LBP core set but applied the environmental ICF categories from the brief LBP core set. Other studies have found contextual factors to be important among patients with LBP [Citation19,Citation62]; this is in accordance with our findings. The advisory group found that the Touch function and Defecation functions were missing in the LBP assessment tool. Touch function has been suggested for inclusion in the comprehensive ICF core set [Citation63], and our study suggests that Defecation functions should also be included. Our study contributes to the on-going discussions regarding the validity of ICF core sets from the perspective of patients and health professionals. Additionally, it underlines the importance of involving patients and health professionals because they focus on different issues when assessing functioning and disability. Furthermore, our study revealed that the background of health professionals was an essential factor in how to perform patient assessment (biopsychosocial vs. biomedical). The LBP assessment tool covered all relevant ICF categories and we believe the tool can facilitate a biopsychosocial approach and assessment regardless of the professional background.

Step 4: piloting

We evaluated three aspects of content validity: relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility during the piloting [Citation40]. Eight patients and five health professionals participated, which is considered “very good” quality (≥7 participants) in accordance with COSMIN ratings for PRO development [Citation40]. However, further evaluation of comprehensiveness will be examined in future research with a larger sample.

Step 5: design and technical production

In this step, we acknowledged the importance of using platforms and technology already known and available to facilitate applicability in clinical practice. Furthermore, we learned that how to display data was just as essential as item generation. Therefore, the patient-profile-LBP was designed parallel to the item generation. Variation in PRO scoring, scaling and presentation is an obstacle to interpretation and application [Citation64]. Hence, we designed the patient-profile-LBP to be easy to interpret from the perspective of both patients and health professionals. Finally, health professionals had the opportunity to use summarised PRO data as part of standard procedure, but our study revealed their reduced use. This is in accordance with previous research emphasising the importance of staff training to facilitate implementation [Citation12,Citation65]. Thus, training will pose an essential element in the implementation of the LBP assessment tool.

Methodological considerations

It was a considerable strength of the LBP assessment tool that it was based on the construct “functioning and disability” as defined by ICF [Citation7] and the relevant content was specified using ICF categories from the validated comprehensive LBP core set [Citation9] and the rehabilitation set [Citation25]. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in the development and thereby, we gained a more complete description and understanding of functioning and disability in patients with LBP. Tailoring the content of the LBP assessment tool to the end-users maximises acceptability and reduces implementation barriers. Moreover, the development process followed established guidelines [Citation27–29] and COSMIN recommendations [Citation40]. To evaluate the quality of the PRO-LBP design, we reviewed the 12-point COSMIN checklist regarding item generation [Citation40]. The ratings showed “very good” methodological quality for all check points. This is contrary to commonly used LBP-specific PRO instruments where content specification has received less attention [Citation65]. Since ICF was proposed, implementing it in healthcare systems has been a goal [Citation66,Citation67]. To achieve this, practice-friendly tools are needed to obtain internationally comparable data of functioning and disability [Citation66,Citation68]. We believe that the LBP assessment tool provides a prototype of such a tool.

This study has some limitations. We used a quantitative approach to define the content by using the ICF core sets as a starting point. However, a qualitative approach including interviews with patients and health professionals could have provided insights into other important perspectives. By asking the patients to complete an initial draft of the PRO-LBP and health professionals to complete an initial draft of the ClinRO-LBP, it could be argued that we primed them, which might have biased their selection of outcomes. Personal factors are not classified in the ICF core sets [Citation9,Citation25]. Thus, relevant items such as age, gender, lifestyle, and comorbidities were selected by the authors on the basis of the current description in ICF [Citation7]. It could be argued that this selection can have underestimated items regarding personal factors in the PRO-LBP. However, personal factors are important in the biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach [Citation69]. This supports our decision to include those items in the PRO-LBP [Citation70]. No patients were directly involved in the development of the patient-profile-LBP. Patient involvement was planned but failed due to recruitment barriers. A previous research examining different presentation formats demonstrated that patients prefer simple line graphs [Citation64], which is in accordance with the format of the patient-profile-LBP. However, patients' perspectives on the usefulness of the patient-profile-LBP could have changed the format. The advisory group did not reflect the multidisciplinary team as no doctors or chiropractors participated. This might have influenced the content of the LBP assessment tool; however, we expect that the following field-testing will reveal if essential information is lacking [Citation26]. Finally, the PRO-LBP was used as a one-time PRO assessment for individual patient care [Citation71]. At this stage, responsiveness of the PRO-LBP is thus unknown.

Conclusions

This study presents the process used to develop the multi-item assessment tool; the LBP assessment tool. This tool is the first to address all ICF components and integrate biopsychosocial perspectives from patients and health professionals. The perspectives of patients and health professionals qualified the content and the design of the LBP assessment tool. The initial evaluation of content validity including face validity showed adequate reflection of the construct. The LBP assessment tool may have the potential to enhance a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach in routine clinical practice among patients with LBP. Further work on the way will evaluate comprehensiveness, acceptability, and degree of implementation of the LBP assessment tool to strengthen its use for clinical practice.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (72.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients and health professionals who generously shared their time and experiences and the Spine Centre for hosting the study. We appreciate the work of research assistant Christina Dam Sørensen for preparing the electronic version of the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP and to Allan Lind-Thomsen for his great work in producing the patient-profile-LBP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy could be compromised, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–2367.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–2383.

- O’Sullivan P, Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan K, et al. Multidimensional approach for the targeted management of low back pain. In: Jull GA, Grieve GP, editors. Grieve's modern musculoskeletal physiotherapy. 4th ed. Edinburg, New York: Elsevier; 2015. p. 465–469.

- Kramer MH, Bauer W, Dicker D, et al. The changing face of internal medicine: patient centred care. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(2):125–127.

- Pincus T, Kent P, Bronfort G, et al. Twenty-five years with the biopsychosocial model of low back pain—is it time to celebrate? A report from the twelfth international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Spine. 2013;38(24):2118–2123.

- Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):468–472.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Stucki G, Cieza A, Ewert T, et al. Application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in clinical practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(5):281–282.

- Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, et al. ICF core sets for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:69–74.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001.

- Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm J. 2012;16(3):49–53.

- Boyce MB, Browne JP, Greenhalgh J. The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(6):508–518.

- Van Der Wees PJ, Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden MW, Ayanian JZ, et al. Integrating the use of patient-reported outcomes for both clinical practice and performance measurement: views of experts from 3 countries. Milbank Q. 2014;92(4):754–775.

- Olde Rikkert MGM, van der Wees PJ, Schoon Y, et al. Using patient reported outcomes measures to promote integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(2):8.

- Espallargues M, Valderas JM, Alonso J. Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: a systematic review of its impact. Med Care. 2000;38(2):175–186.

- Valderas JM, Alonso J, Guyatt GH. Measuring patient-reported outcomes: moving from clinical trials into clinical practice. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):93–94.

- Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–193.

- Wheat H, Horrell J, Valderas JM, et al. Can practitioners use patient reported measures to enhance person centred coordinated care in practice? A qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):223.

- Calmon Almeida V, da Silva Junior WM, de Camargo OK, et al. Do the commonly used standard questionnaires measure what is of concern to patients with low back pain? Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(10):1313–1324.

- Ibsen C, Schiottz-Christensen B, Melchiorsen H, et al. Do patient-reported outcome measures describe functioning in patients with low back pain, using the Brief International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set as a reference? J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(7):618–624.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Sussex R. Disentangling disability in the fear avoidance model: more than pain interference alone. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(3):273–274.

- Wang P, Zhang J, Liao W, et al. Content comparison of questionnaires and scales used in low back pain based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(14):1167–1177.

- Taylor AM, Phillips K, Patel KV, et al. Assessment of physical function and participation in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(9):1836–1850.

- Grill E, Stucki G. Criteria for validating comprehensive ICF core sets and developing brief ICF core set versions. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(2):87–91.

- Prodinger B, Cieza A, Oberhauser C, et al. Toward the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Rehabilitation Set: a minimal generic set of domains for rehabilitation as a health strategy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):875–884.

- Ibsen C, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Nielsen CV, et al. Assessment of functioning and disability in patients with low back pain – the low back pain assessment tool. Part 2: field-testing. Disabil Rehabil. 2021. DOI:10.1080/09638288.2021.1913649

- Elwyn G, Kreuwel I, Durand MA, et al. How to develop web-based decision support interventions for patients: a process map. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):260–265.

- de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Chapter 3: development of a measurement instrument. In: De Vet H, Terwee C, Mokkink L, et al., editors. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide (Practical Guides to Biostatistics and Epidemiology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 30–64.

- Rothrock NE, Kaiser KA, Cella D. Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(5):737–742.

- Fayers PM, Hand DJ. Causal variables, indicator variables and measurement scales: an example from quality of life. J R Stat Soc A. 2002;165(2):233–261.

- Eboli L, Forciniti C, Mazzulla G. Formative and reflective measurement models for analysing transit service quality. Public Transp. 2018;10(1):107–127.

- Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(9):1311–1321.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194.

- Schnohr CW, Rasmussen CL, Langberg H, et al. Danish translation of a physical function item bank from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017;3(29):29.

- Schiøler G, Dahl T. ICF. International Klassifikation af Funktionsevne, funktionsevnenedsaettelse og helbredstilstand. 1st ed. Copenhagen: Muncksgaard Denmark; 2003.

- Willis GB, Artino AR Jr. What do our respondents think we're asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):353–356.

- Ibsen C, Schiottz-Christensen B, Maribo T, et al. "Keep it simple": perspectives of patients with low back pain on how to qualify a patient-centred consultation using patient-reported outcomes. Musculoskeletal Care. 2019;17(4):313–326.

- Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. New York: Routledge; 2016.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745.

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. Self-reported disability according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Low Back Pain Core Set: test–retest agreement and reliability. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(4):621–626.

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Terwee CB, et al. Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index: which has better measurement properties for measuring physical functioning in nonspecific low back pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1620–1637.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911–1920.

- Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271–273.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. What do clinicians consider when assessing chronic low back pain? A content analysis of multidisciplinary pain centre team assessments of functioning, disability, and health. Pain. 2018;159(10):2128–2136.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J, Meredith PJ, et al. Rasch analysis supported the construct validity of self-report measures of activity and participation derived from patient ratings of the ICF low back pain core set. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;84:161–172.

- Gao Y, Yan T, You L, et al. Developing operational items for the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Rehabilitation Set: the experience from China. Int J Rehabil Res. 2018;41(1):20–27.

- Prodinger B, Scheel-Sailer A, Escorpizo R, et al. European initiative for the application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: development of clinical assessment schedules for specified rehabilitation services. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(2):319–332.

- Selb M, Gimigliano F, Prodinger B, et al. Toward an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health clinical data collection tool: the Italian experience of developing simple, intuitive descriptions of the rehabilitation set categories. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(2):290–298.

- Stucki G, Prodinger B, Bickenbach J. Four steps to follow when documenting functioning with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(1):144–149.

- Ramasamy A, Martin ML, Blum SI, et al. Assessment of patient-reported outcome instruments to assess chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2017;18(6):1098–1110.

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, et al. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20(3):245–263.

- Chiarotto A, Ostelo RW, Boers M, et al. A systematic review highlights the need to investigate the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures for physical functioning in patients with low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;95:73–93.

- Chiarotto A, Terwee CB, Kamper SJ, et al. Evidence on the measurement properties of health-related quality of life instruments is largely missing in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;102:23–37.

- Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, et al. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;41:1–10.

- Cieza A, Hilfiker R, Boonen A, et al. Items from patient-oriented instruments can be integrated into interval scales to operationalize categories of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):912–921.

- Okochi J, Utsunomiya S, Takahashi T. Health measurement using the ICF: test–retest reliability study of ICF codes and qualifiers in geriatric care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3(46):46.

- Bautz-Holter E, Sveen U, Cieza A, et al. Does the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for low back pain cover the patients' problems? A cross-sectional content-validity study with a Norwegian population. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(4):387–397.

- Prodinger B, Stucki G, Coenen M, et al. The measurement of functioning using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: comparing qualifier ratings with existing health status instruments. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):541–548.

- Lygren H, Strand LI, Anderson B, et al. Do ICF core sets for low back pain include patients' self-reported activity limitations because of back problems? Physiother Res Int. 2014;19(2):99–107.

- Abbott AD, Hedlund R, Tyni-Lenné R. Patients' experience post-lumbar fusion regarding back problems, recovery and expectations in terms of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1399–1408.

- Røe C, Sveen U, Kristoffersen O, et al. Testing of ICF core set for low back pain. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2008;128(23):2706–2708.

- Brundage MD, Smith KC, Little EA, et al. Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2457–2472.

- Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med. 2014;28(2):158–175.

- World Health Organization. WHO global disability action plan 2014–2021 – better health for all people with disability; 2015. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/199544/9789241509619_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0398FD6A933B6D79E313B1968F2DE692?sequence=1

- Imamura M, Gutenbrunner C, Stucki G, et al. The International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine: the way forward – II. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(2):97–107.

- Ustun B, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N. Comments from WHO for the Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine Special Supplement on ICF Core Sets. J Rehabil Med. 2004;(44 Suppl.):7–8.

- Leonardi M, Sykes CR, Madden RC, et al. Do we really need to open a classification box on personal factors in ICF? Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(13):1327–1328.

- World Health Organization. How to use the ICF: a practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Exposure draft for comment. WHO; 2013; [updated 2013 Oct]. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/drafticfpracticalmanual.pdf

- International Society for Quality of Life Research (prepared by Aaronson N ET, Greenhalgh J, Halyard M, Hess R, Miller D, Reeve B, Santana M, Snyder C). User’s guide to implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice; 2015; [cited 2020]. Available from: https://www.isoqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2015UsersGuide-Version2.pdf