Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore factors that influence participants’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance with healthcare professionals; their participation in the alliance; and their commitment to treatment in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation setting.

Materials and methods

A qualitative research-design was used and 26 participants in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program were interviewed in-depth.

Results

Initially, participants reported to be satisfied with their healthcare professionals. After deeper reflection on the therapeutic alliance, several unspoken thoughts and feelings and relational ruptures emerged. Almost all participants mentioned a history of disappointing and fragmented healthcare, and they reported on how this affected their cognitions, perceptions, and beliefs about the current program. Participants felt insufficiently empowered to voice their concerns and regularly chose to avoid confrontation by not discussing their feelings. They felt a lack of ownership of their problems and did not experience the program as person-centered.

Conclusions

Several factors were found that negatively influence the quality of therapeutic alliance (agreement on bond) and efficacy of the treatment plan (agreement on goals and tasks). To improve outcomes of pain rehabilitation, healthcare professionals should systematically take into account the perceptions and needs of participants, and focus more on personalized collaboration throughout the program offered.

Differences in perceptions and experiences of pain, together with differences in beliefs about the causes of pain, negatively influence the therapeutic alliance.

When participants and healthcare professionals operate from different paradigms, it is important that they negotiate these differences.

From the perspective of participants, a clear-cut organization of healthcare that encourages collaboration is required.

It is important to focus on personalized collaboration from the start and during treatment, and to recognize and discuss disagreement on diagnosis and treatment plans.

During this collaboration, healthcare professionals should systematically take into account the perceptions and needs of the participants.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

In the past decades it has been shown that a strong therapeutic alliance increases treatment effects, with most evidence embedded in psychotherapy, psychology, and mental health research [Citation1]. In psychotherapy therapeutic alliance has been defined by Bordin (1979) as a negotiated, collaborative feature of the treatment relationship that enables the participant “to accept and follow treatment faithfully” [Citation2]. The therapeutic alliance includes three domains: level of agreement between participant and healthcare professional on the goals of the treatment and on tasks (to pursue the proposed goals), and quality of the bond between participant and healthcare professional [Citation2]. Clinically, the therapeutic alliance is a dynamic relationship in which building, maintaining, and repairing the collaboration between participant and healthcare professional are important features to strengthen the therapeutic relationship [Citation3]. Transient or longer-lasting strains in a therapeutic relationship are very common and may result in ruptures in the therapeutic alliance [Citation4]. Ruptures refer to misunderstandings, tensions, and conflicts between participant and healthcare professionals, and vary in intensity from minor tensions in the collaboration to a major breakdown of the therapeutic relationship [Citation5]. The theory of therapeutic alliance suggests that therapeutic relationships must be build, maintained, and also repaired. Repairing the therapeutic relationship acts as a vehicle to facilitate treatment effects, to improve function, and to reduce disability [Citation3]. This theory also suggests that the therapeutic alliance is relevant for all types of healthcare disciplines and treatment relationships [Citation1,Citation2].

Different studies suggest the potential of the therapeutic alliance in affecting rehabilitation outcomes in stroke-, cardiac-, and musculoskeletal rehabilitation, diabetes management, and chronic pain [Citation6–9]. These outcomes include psychosocial and biomedical outcomes such as depression, self-efficacy, adherence to treatment, physical functioning, pain intensity, and general health status [Citation6,Citation10]. Qualitative studies have shown context specific aspects within different rehabilitation disciplines that are important for how rehabilitation participants engage in treatment. For example, in pediatric rehabilitation, three interrelated aspects were found to be important regarding the therapeutic alliance and were identified from the perspective of the children, their parents and their pediatric physical therapists, namely; importance of trust in the healthcare professional, transparency in sharing information, and negotiation about goals and tasks of the treatment [Citation11]. In stroke rehabilitation, the therapeutic alliance appeared to consist of three interrelated components; personal connection, professional collaboration, and family collaboration [Citation12].

In multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation several professionals are involved in the treatment of an individual participant (e.g., physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and psychologist), and participants therefore have to handle multiple treatment relationships. Within the various therapeutic processes, each healthcare professional has a different role. In addition, negotiation about treatment goals and tasks is not only necessary between the rehabilitation participant and multiple healthcare professionals but also between these healthcare professionals. Because of these aspects, it is valuable to deepen our understanding of the specific aspects of the therapeutic alliance in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation setting.

Additionally, since multidisciplinary treatment programs for chronic pain vary in their effectiveness in reducing disability and improving quality of life of their participants, more understanding of the role of the therapeutic alliance is important [Citation13,Citation14]. Although multidisciplinary treatment programs for chronic pain are more effective compared to other monodisciplinary treatments, the differences in effect sizes are small [Citation14,Citation15]. Previously, it has been suggested that improvements in clinical outcomes are influenced by how rehabilitation participants relate to their healthcare professionals in the therapeutic alliance [Citation6,Citation16]. Moreover, previous qualitative research within pain rehabilitation showed that there is a need for more collaboration between healthcare professionals and the rehabilitation participants, not as a passive target, but as an active participant in the therapeutic process [Citation17].

To the best of our knowledge, little empirical research has been conducted on the therapeutic alliance in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation setting. It is unknown how rehabilitation participants perceive the therapeutic alliance with their healthcare professionals, how they experience their own participation and commitment to the treatment and which interpersonal dynamics affect the willingness of the rehabilitation participant to engage actively in the therapeutic process. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore factors that influence participants’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance with healthcare professionals, their participation in the alliance, and their commitment to treatment in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation setting.

Materials and methods

Design

Although substantial evidence exists on the role and importance of the therapeutic alliance in healthcare in general, in the current study we want to explore how this phenomenon is perceived and experienced by the persons participating in a multidisciplinary pain program, from the assumption that effectiveness of this kind of program is lower than might be expected. Therefore, we have chosen for purposively sampling (see “sampling and recruitment”), in-depth interviews with participants; and interviews to be taken at the location of the rehabilitation center where participants followed a multidisciplinary pain program (a proxy of the “natural context”). We based our design on principles of “interpretive paradigm” [Citation18]. This method includes iterative data collection, theoretical memoing, and data saturation, as well as the idea that the information that occurs is, in a way, a construction of participant and researcher together (as they interact and influence each other during the course of the interviews). In this type of iterative data-collection the researcher acts as “subjective instrument [Citation19,Citation20]. Additionally, peer-debriefing was applied from the start of the interviews. The interviewer (DP) regularly discussed his experiences, impressions and findings in between the interviews with a clinically experienced senior researcher (GP), until saturation of information was assumed to be reached [Citation21]. With this type of design, we apply the ontological assumptions of “multiple realities”, which are constructed, complex and context dependent. In the current study multiple realities apply to the perception from the rehabilitation participant point of view, on the role and importance of the phenomenon “therapeutic alliance” (goals, tasks, and bond). In interviews and analyses we searched for notable issues, themes, patterns or dynamics from the rehabilitation participant’s perspective. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the UMCG (M17.217913).

Context of the pain rehabilitation program

The 12-week multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program of the Center for Rehabilitation of the University Medical Center Groningen (The Netherlands) aims to decrease disability, increase participation, and improve quality of life of persons experiencing chronic musculoskeletal pain. The program is based on cognitive behavioral principles; it includes thorough pain education and focus on self-management capacities concerning pain and disability. This program is in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines of International Association for the Study of Pain [Citation22]. Such programs are applied, in varieties, in many (western) countries [Citation23]. The program takes place in a weekly one-to-one setting. A detailed description of the program is provided in Supplementary material 1.

Sampling and recruitment

The participants of this study were purposefully selected aiming at heterogeneity in disability status, duration of chronic pain, gender, age, education level, and working status. Generally, participants were eligible for inclusion if they were admitted to the pain rehabilitation program, had followed the program for at least six weeks, to ensure that they had participated in multiple treatment sessions with their healthcare professionals (for participants who had stopped the program earlier, a minimum of two weeks was applied), were able to communicate and write in Dutch, had a history of earlier treatments for their pain complaints, and were at least 18 years of age. Potential participants were invited to this study by their rehabilitation physician. The recruitment period was from March 2017 to May 2019. During the iterative process of data collection and analyses also theoretical sampling was conducted, enabling exploration of preliminary ideas and to unfold relevant materials and refine interpretation of the data [Citation24]. For example, in the first four interviews the interviewer missed depth, dynamics, ambivalence and/or controversy in the reactions of the participants, as might be assumed based on the theory of Bordin and Safran et al. [Citation2,Citation4]. In peer-debriefing we assumed that “avoidance” of the inner tension (within the participant) and relational tension (between respondent and healthcare professional) might play a role. Therefore, we sought for ways to deepen the interviews. This assumed avoidance-tendency was taken into account during selection of the participants, and was thematized in the forthcoming interviews. Additionally, somewhat later in the course of the interviews, we especially included participants with a high or low effectiveness of the treatment, in order to be able to search for more dynamics in the therapeutic alliance.

Data collection

Prior to the interviews, participants were informed that their data would be anonymized and that their healthcare professionals would not be informed about the content of their interviews. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Interviews were conducted in the treatment rooms of the pain rehabilitation program. Before the interviews, the Working Alliance Inventory Rehabilitation Dutch Version (WAI-ReD) [Citation25], was filled out twice by participants, once concerning the professional with whom they experienced the most positive therapeutic alliance, and once concerning the professional with whom they experienced the least positive alliance (higher scores indicate a stronger and more positive therapeutic alliance). Thereafter, face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted by the first author (DP). All interviews were audio-recorded. Field notes were made to record impressions of the interviews and were used to prepare the next interviews.

In the interviews, participants were asked: “How do you experience your relationships with healthcare professionals, previous as well as current?” In the first four interviews, we missed reflection, ambivalence and dynamics concerning the therapeutic relationship. Therefore another question was asked first “Can you walk me through your history of experiencing (chronic) pain?” By adding this question the interviews became more sensitive. Participants generally expressed more affect and commented on their emotions, attitudes, and perceptions concerning their prior or current treatment. They also began to talk about the role of the therapeutic relationship. At the end, the WAI-ReD scores were used to reflect upon by the participant and to compare the scores with the content and tendency of the interview.

Participants’ characteristics (gender, age, education level, duration of chronic pain, working status, disability status (Pain Disability Index), and level of central sensitization (Central Sensitization Inventory) were obtained directly from the participants or from their medical records [Citation26,Citation27].

Analyses

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim (DP). Atlas.Ti (version 5.2) was used for data analyses. To explore the therapeutic relationship transcripts were analyzed in three phases by open, axial and selective coding[Citation18]. Open coding was applied line by line, and the initial codes were kept very close to the text, and the descriptive labels were assigned to small segments of data. Thereafter, axial coding was applied by grouping codes in categories and making connections between categories (including reanalysis of codes, and merging codes and categories). Last, selective coding was applied by searching for connections between categories to identify patterns and themes or dynamics from the rehabilitation participant point of view, on the role and importance of the phenomenon “therapeutic alliance” (goals, tasks, and bond). Deductive strategies were used to analyze the data with regard to the theory of the therapeutic alliance. Coding involved constant comparison, comparing data within and between participants, and comparing data with theory to identify indicators that emerge a pattern of themes. During the iterative consensus coding process, data from interviews and field notes were used. The first and the second author independently coded and analyzed all transcripts, and the evolving codes were repeatedly discussed in consensus meetings with the whole team, which took place during each phase of the data analyses: open-, axial-, and selective coding. The research team aimed for theoretical (data) saturation, which was assumed when no new categories were found and existing categories were fully defined [Citation28]. When saturation was assumed, two additional interviews were conducted.

Results

Thirty-seven potential participants were contacted, of whom 26 participated in the study (). Reasons for not participating in the study were: not starting with the pain rehabilitation program (n = 2), leaving the pain rehabilitation program because pain or pain-related problems ceased to exist and participated in the program less than two weeks (n = 2), leaving the program for job related issues (n = 2), and rejecting participation in the interview because of dissatisfaction with the rehabilitation program (n = 3). Two participants were excluded because they had no history of earlier treatments. Interviews lasted 70 min on average (range 53- 95 min).

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 26).

The two WAI-ReD scores are summarized in . In general, relatively high total scores and high domain scores were reported for the both healthcare professionals with whom the participant experienced the most- and less positive alliance.

Table 2. Difference between 2 healthcare professionals from participants’ perspectives (n = 26).

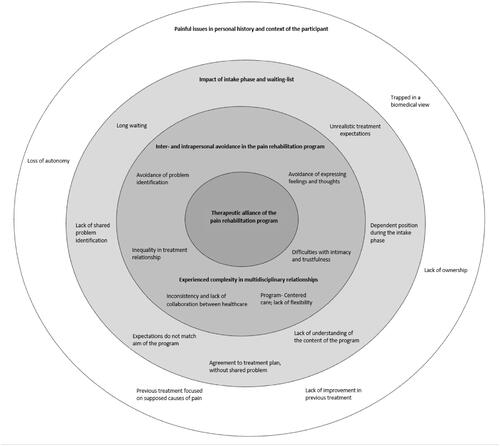

Themes, affecting engagement in the therapeutic alliance from the perspective of the participants were identified and are summarized in . These themes were related to painful issues in personal history and context of the participants, impact of intake and waiting-list, inter- and intrapersonal avoidance in the pain rehabilitation program, and experienced complexity in multidisciplinary relationships.

Figure 1. Participants’ perceptions affecting engagement in the therapeutic alliance in pain rehabilitation program.

Painful issues in personal history and context of the participants

At the start of the interviews, current and former healthcare-related therapeutic relationships were not at the center of participant’s concerns. Initially, participants reported to be satisfied with the therapeutic relationships (which was in line with the high WAI-ReD scores reported prior to the interview, see ), and tended to have a distanced attitude toward discussing this topic. They expressed that their struggle with pain in the course of their life (social and family life, daily activities, and work) was at the center of their concerns. It appeared that, painful issues in the personal history and context of the participants played a pivotal role in the participants perception of their relationships with their healthcare professionals in the current program (). Also previous experiences with healthcare professionals affected participants’ illness representations and their perception of healthcare relationships in general.

Almost all participants reported about a long period in which they suffered disability due to their pain, and they all had a substantial history of different healthcare treatments. This history and personal narrative shaped their cognitions, perceptions, and beliefs about the causes of their pain, as well as their current treatment expectations. In general, participants felt that their previous treatments were based on, or in trapped in a biomedical view that focused on treating supposed (biological) causes of pain. In those previous, biomedical oriented treatments participants had a more or less passive role, which affected their role and participation in the current cognitive behavioral treatment.

Participant (P) 5: […] “In the private MRI center, I was told that my intervertebral disc was too thin. That’s what the doctor told me. Next, I went back to the university hospital nearby. I had a new scan there. It turned out that my intervertebral disc was not too thin after all”

Interviewer (I): “This situation, how did it make you feel?”

P: “It really sucks! I thought I had something, but then, I was back to square one… I knew just as little as before [silent for a few seconds]…”

Most participants felt that their autonomy was reduced by the stress caused by their chronic pain and disability. The degree of personal and social stress depended on the severity and impact of pain and disability, the pressure it exerted on the participants’ interpersonal capacities, reduced participation in life activities, and the decrease in quality of social support. The most frequently mentioned factors resulting in loss of autonomy in the medical context were uncertainty about the diagnosis and/or lack of a clear diagnosis, uncertainty about the reduction of pain, and ineffectiveness of previous treatment(s). Participants felt trapped between hope for improvement and fear of further deterioration. From the narratives of the participants it became clear that these feelings of loss of autonomy further increased dependency of participants on their healthcare professionals resulting in a more unequal relationship.

Participants experienced a lack of ownership of their own disability, which seems related to their perceived lack of conversation, discussion, or participation in prior treatments. Through previous negative treatment experiences some participants had lost trust in their diagnostics outcomes, or in expecting cure for the supposed causes of their pain, or any long-term effects of any treatments of their pain. As a result, they felt a lack of ownership of previous treatment processes, and became increasingly passive in response to those treatments. These feelings led to a reduction in self-esteem and a negative self-image. Also, participants were reluctant to expect a positive outcome of the multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program, affecting the way they engage within their current therapeutic relationships.

P22: […] “In the first week my pain only increased [after the injection]. Thereafter, I had the idea that it had helped a bit; the pain decreased. But that was only for a short period of time and the pain returned. I was told ‘You have to wait for at least 3 months to see whether there is an effect……….’ Then I got a TENS., stickers on my back, with electric current running through it… To make a long story short… No or little effect. Even with the highest-intensity TENS… no effect on my pain experiences at all… [2 second of silence]…. And then… the doctor [mentions name of the doctor] did not have anything to offer me anymore…”

From these previous experiences many participants indicated that they were familiar with a paternalistic attitude of healthcare professionals and were used to functional and superficial interaction within the therapeutic relationships. From these experiences, participants had learned that they only played a minor role in the treatment process and in the eventual handling of their complaints. The messages they heard were “the healthcare provider knows best” and “I am not a professional.”

In participants’ narratives about previous healthcare experiences, considerable strains or ruptures in therapeutic relationships came to light. Most participants emphasized they preferred to avoid confrontation with their healthcare professional when they felt anger or frustration, instead of expressing their true feelings.

P17: […] “The physician was sitting in front of me (bending over), and I felt myself getting smaller and smaller… In the end he said: ‘well you have to (learn) to live with it’… I didn’t say anything else. I have dealt with it, for more than 20 years (talks in a different voice). But I can’t take it anymore. It hurts and I am tired. Yes… I still have to learn to cope with that. And yes, I ran away from it… Well, I don’t know what to do. Apparently, no one seems to know what to do…”

I: “After that, did you go back to your general practitioner?”

P: “Not immediately… Thereafter, I felt defeated… I felt his eyes piercing my back. The eyes of that man [physician]!”

Only a few participants reported they had a confrontation with their healthcare professional after expressing their true feelings. However, participants emphasized that their previous relationship with healthcare professional influenced their relational trust in (current) healthcare professionals.

P15: […] “Well, he [physician] just told me… I am a poser. I said, okay… And he says, it was all between my ears, I was crazy… I said: I’m not crazy. And the physician talked in the hallway about my medical file. I said that’s not okay. He said: ‘well, if I want to do that, I will do it.’ And I said, I will not visit you again. […] I went to my general practitioner and then it was all over; he [general practitioner] said ‘you don’t have go there anymore…”

Impact of the intake phase and waiting-list

The previous healthcare experiences (including painful issues in history and the context of the participant) shaped participants’ individual illness representations and their individual perceptions of relationships with healthcare professionals. These previous experiences generally tempered expectations of the current program but expectations differed between participants. Two types of expectations were frequently mentioned, either low expectations regarding the effectiveness of the treatment or high expectations. In case of low expectations, participants felt there was “no harm in trying”, they lost hope due to earlier failing treatments. In case of high expectations the program was hoped to be “the Holy Grail.” Low expectations were mostly expressed by participants who had lost confidence in all other treatments.

P15: […] “I wanted to join the pain rehabilitation program, but I was afraid that it would happen again… I was afraid that this treatment would not work either… My hopes had been destroyed several times… And then what? …Then I am alone again, with my pain …”

High expectations were expressed by participants who expected (too) much from the program and/or the academic setting and saw the rehabilitation program as a last treatment option. These expectations were further strengthened by the long waiting list, which gave some participants the idea that “If the waiting list is that long, the program must be very good.” The name pain rehabilitation led participants to expect a focus on pain relief combined with additional diagnostics on the causes of pain. Almost all participants spontaneously expressed their displeasure and concomitant uncertainty about the duration of the waiting list. They emphasized that being on the waiting list had a negative impact on their lives. The waiting list seemed to reinforce the unequal relationship between participant and healthcare professionals. Some participants felt they had to demonstrate certain types of behavior in order to be accepted into the program.

P12: […] “They [healthcare professionals] say…: ‘that person [the participant herself] has already gone through a whole process leading up the program.’ …Yes… That is true and it [the process] takes even longer now… They say: ‘you’ve already had several treatments and diagnostic exams…’ Yes. I hear that every time, but in the end, it does not speed up anything…”

I: “It’s hurting you, isn’t?”

P: “Yes… Yes… [Silent for a few seconds]… Yes, and I wonder whether I am the only one for whom it takes so long? ……. I don’t know … The whole journey to this program was terrible…”

These unrealistic treatment expectations in combination with frustrations about the long waiting list, affected participants’ attitude (aloof and avoidant) and role-taking ability in the therapeutic relationships with their current healthcare professionals.

Despite extensive pain education and explanations, verbally and in writing, about the content and goal of the program from the rehabilitation physician’s side before screening, participants appeared to have little knowledge and understanding of the actual content of the pain rehabilitation program. This lack of knowledge and understanding complicated transparent negotiations on goals and tasks between participant and rehabilitation professionals in the intake phase. Participants also reported that the intake process went too fast: the problem identification and proposal of the treatment plan (formulated in the next appointment after the intake) followed a mere week after three screening interviews, with three different healthcare professionals (all in one day). Despite the fact that the goals seemed to be jointly set, and agreement on goals was checked by the rehabilitation physician after the screening, it remained difficult for the participants to comprehend what exactly they had agreed upon. Notably, the expectations of many participants (reduction of pain) fundamentally differed from the aim of the program. This difference emphasized a lack of agreement on goals. During the interviews it was clear that talking about these former issues evoked emotions in some participants, they expressed displeasure or coped with their emotions by taking distant attitude.

Inter- and intrapersonal avoidance in the pain rehabilitation program

Previous encounters with healthcare systems had led many participants to consider these systems as top-down and depersonalizing. They did not feel involved in the diagnostic process and felt excluded from the points of view of the professionals. The current pain rehabilitation program was perceived as a one-sided affair, in which the participants had neither been offered nor experienced a great deal of involvement. They anticipated on new setbacks in the treatment, to protect themselves from further disappointments, in combination with their long history of failing treatments, this resulted in a passive and distanced attitude toward the current pain rehabilitation program.

In the interviews concerning this issue, a discrepancy emerged between what participants initially said about the program and what they actually thought, which only emerged later in the interviews. It appeared that a great deal of avoidance took place, also in therapeutic relationships which the participants indicated as “satisfactory”. This avoidance was expressed in different levels: engagement in the program, avoidance of personal feelings, as well as avoidance of transparency and intimacy in the therapeutic relationship. For instance, some participants mentioned they avoided to attend to their own feelings and fears, and therefore did not express these to their healthcare professionals either.

P12: […] “I have been afraid for some time that I will develop a spinal cord injury…”

I: “Did you share your fears with your healthcare professionals?”

P: “No… No…”

I: “Do you have an idea why not?”

P: “Uhm… Yes well… I don’t like to talk about it that much.”

Other participants reported that they did not feel comfortable enough to express their feelings and/or thoughts.

P21: […] I: “Do you experience difficulties in expressing feelings or thoughts during the rehabilitation program?”

P: “Uhm… Yes. A few times.”

I: “And… What happens then?”

P: “Then it’s as if I shut down……… Even though I am someone who talks a lot and says quite a lot… I often change the topic.”

Some participants mentioned that they were afraid to admit their personal feelings, because the professionals might act upon this.

P20: […] “Perhaps I have more fears than I want to admit. If you surrender to your fears then they really exist… And if I bring it [the fears] into the conversation, they [professionals] may want to use it in the treatment. I don’t know if I want that to happen”

Although quite implicitly experienced by the participants, these levels of avoidance of expressing feelings and/or thoughts can be interpreted as a sign of stagnation, strain or rupture in the therapeutic alliance. The majority of the participants reported to have experienced a considerable deterioration in a therapeutic relationship with at least one healthcare professional. A frequently mentioned factor leading to deterioration in the therapeutic relationship was the switch between different professionals within the same discipline because of illness of healthcare professionals, scheduling issues, or other reasons. Participants indicated that they did not always openly discuss these strains or ruptures. They left their thoughts and feelings unspoken and chose to avoid confrontation in most circumstances.

P19: […] “But as soon as I get an advice from her [substitute occupational therapist, because of illness], more or less a repetition of what I told her, I mentally withdraw and I say ‘yes’ right away and do not talk about the things that really bother me…”

Some participants mentioned that they had problems with vulnerability and intimacy, and therefore kept professionals at a distance; they took a passive, adjusted and submissive role in the therapeutic alliance, to avoid personal issues concerning their difficulties in joining the program.

P27: […] “… Sometimes I come across as hard and cold apparently… but actually, I’m none of these things. But that is how I am perceived sometimes… people feel uncomfortable with me… […] As a result, the relationship remains superficial [during the rehabilitation]… I wait and see…”

Some participants developed a dependent, passive, even surrendering relationship with their healthcare professionals. In those relationships, participants offer their autonomy and leave the ownership of their problems to their healthcare professionals, which is in fact not the goal of the treatment, namely focus on self-management capacities concerning pain and disability.

P23: […] “I am going here [rehabilitation program]; I look at the schedule to see what time I have to be here or there. […] I just endure it… Let me just say it like that. Really, I undergo it… I am all right with it. I just do it as well as I possibly can. […] I assume they know the best; they do this more often and with more people.…. There are lots of other patients like me. I think they [the healthcare professionals] are specialists and know what they are talking about. I just assumed that. […] I keep that in mind now, and I will just have to see whether it is right. I have surrendered to it, and I will do everything to get rid of it [the pain].”

Also the focus on the biopsychosocial, cognitive-behavioral approach in the current program was unclear and difficult for many participants, as most participants reported that they were used to a biomedical view from their previous healthcare experiences. These differences in presumed approaches between by participants and healthcare professionals, together with still more or less top-down treatment-proposal, resulted in incoherent perceptions, interpretations, and beliefs regarding the issue of pain and effective pain treatment. During the interviews, many participants reported that they did not, or only partially, agreed with the healthcare professionals in the problem identification, but did not discuss these issues.

P4: […] “In treatment, I have often heard that it’s all in my head. But I feel the problem is in my back, really!”

P14: […] “You are here to learn how to deal with the pain and not to look for its causes. [Silent for a few seconds]… Anyway, I underwent a scan: no hernia. Rheumatologists said it’s not rheumatism… I still have a feeling [points to her back] that there must be someone who can manipulate my back… For example, a physiotherapist who does something different from what has been done so far, which will reduce my pain.”

Since the overall aim of the program was to cope with pain complaints, and not reduce pain, some participants described they felt unable to discuss their desire for pain-reduction, because they had already signed on to the program. Participants indicated they were satisfied with the program because the help and attention they received from professionals enabled them to cope with their problems in life. Nevertheless, many participants felt that their real problem in life was pain, which made the rehabilitation program less important. This crucial disagreement on problem identification remained mostly latent, however, it influenced the commitment to the program gravely and therefore the therapeutic alliance. In some participants, this issue was more manifestly present and was discussed between the participant and the healthcare professional(s), sometime leading either to consensus or conflict.

Experienced complexity in multidisciplinary relationships

An important finding was that most of the participants experienced difficulties in critically evaluating the relationship with their healthcare professionals. They sometimes contradicted themselves. For example, when participants mentioned a deterioration in the relationship with a certain professional, they subsequently played this down or mentioned they experienced no problems. After some prompting, participants mentioned that it was difficult for them to explain about their different relationships with different professionals. Moreover, participants struggled to find words, resulting in moments of silence and an altogether less coherent conversation. Some participants tried to alleviate their discomfort by changing the topic. Others became inconsistent in their statements. A majority of participants felt a conflict of loyalty when addressing negative feelings or thoughts about the treatment, even when they expected no or small treatment effects.

The WAI-ReD was filled out twice by the participants, once concerning the most positive therapeutic alliance (higher scores) and the other concerning the least positive alliance (lower scores) (). However, in many cases this difference in scores was not confirmed in the interviews. Some participants found it difficult to indicate differences between the relationships with the different professionals beforehand. Some indicated that to them it felt more like they were engaged in a relationship with the entire treatment team (team alliance). Participants considered consistency and mutual collaboration between healthcare professionals to be important aspects contributing to team alliance.

P19: […] “It is a team that works together, and they look at your problem from all angles very thoroughly… It works for a lot of people, so why not for me? Prior to this program, you went to the individual therapies or practices… […] Sometimes you were squeezed into their [earlier treatment] program… It feels like that. Here, the program is more structured. Everything I discuss and do will be evaluated with all professionals.”

Other participants experienced a different therapeutic relationship with each of the professionals. Some mentioned that one specific professional came much closer to them than others, resulting in a stronger therapeutic alliance with this professional.

P3: […] “The psychologist also focuses on other things that are related to my past and influence my current problem. She really is the queen [most important healthcare professional], and the others [remaining healthcare professionals] are all followers…”

Each participant had a different professional who was most important to him or her; often, this was the professional the participant expected to make the most progress with.

A few participants indicated that the strength of the therapeutic alliance changed during the program. For instance, the relationship with a specific professional became more important over time. In contrast, other participants expressed they had no further need for help from a specific professional. During the interview they wondered why they continued treatment with this professional because it did not benefit them.

Participants experienced the pain rehabilitation program as a more or less standardized program with limited flexibility to adjust duration, frequency, and goals of the treatment. Sometimes this standardization gave participants the feeling of program-centered care as opposed to person-centered care, which also influenced participants’ perceptions of their own role during the treatment.

P27: […] “Of course, they [rehabilitation professionals] work from a multifactorial perspective. And you know, one factor is more important for me than the other factors… You know that in advance. And they know it too. But the program is a package deal and you just have to deal with all the factors as they come.”

Discussion

In this qualitative study we explored factors that influence participants’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance with their healthcare professionals and their participation in the therapeutic alliance within a pain rehabilitation program. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study within pain rehabilitation identifying themes which were important from the perception of the participants on the quality of therapeutic alliance. This study indicated that painful issues in personal history and context of the participants, impact of intake and waiting-list, inter- and intrapersonal avoidance in the pain rehabilitation program, and experienced complexity in multidisciplinary relationships were important factors according to rehabilitation participants. Previous research has shown that the quality of the therapeutic alliance is an important predictor of the effectiveness of therapies in any therapeutic context [Citation6,Citation29,Citation30]. This study, however, found that many participants of the pain rehabilitation program did not experience a clear or helpful therapeutic alliance with their healthcare professionals, neither in the past nor in the current program. Moreover, participants were not used to reflecting on the therapeutic alliance and its association with treatment effects. The participants scored relatively high on the WAI-ReD, indicating high therapeutic alliance. However, during the interviews, it became clear that these scores were based on superficial responses of the participants, regarding to kindness and attention from healthcare professionals. Deeper reflection of the participants during the interviews brought to light ruptures in the therapeutic relationships.

The interviews showed that participants’ history of pain was a combination of their treatment (consisting of unsuccessful, fragmented, and ultimately disappointing interventions) and a personal history (characterized by the negative impact of pain problems). This history had not only negatively influenced their personal illness representations, but also distorted their perceptions of the function and aim of the relationship with (previous or current) healthcare professionals. Generally, participants experienced these relationships as top-down. They did not share the view of professionals on the pain diagnosis nor did they feel involved in the treatment plan. These negative expectations, together with a long waiting list, resulted in quite a passive and avoidant attitude in most of the participants. They avoided both their own negative feelings concerning their pain history and problems and their negative feelings concerning the treatment plan and healthcare professionals. Some participants had very low expectations, while others had unrealistically high expectations of the pain rehabilitation program. Nevertheless, most participants did not experience a cooperative relationship with clear-cut goals and tasks, despite the fact that the goals were co-formulated by the participants themselves. Summarizing, participants’ experiences contradicted with the aim and proposed course of the rehabilitation program, in which participants were expected to participate actively.

Negotiation on participants’ perception on coping with pain

The pain rehabilitation program aims to teach participants how to reflect on their behavior and offers them coping strategies concerning their pain-complaints (Supplementary material 1). This helps them to better cope with their chronic pain and improve quality of life and participation in activities of daily living. The interviews showed that participants neither fully comprehended, nor accepted this treatment focus. They considered their chronic pain to be a physical problem mainly, and they did not accept the suggested link between chronic pain, their own behavior, and other coping strategies regarding pain. These cognitions were reinforced by many previous healthcare experiences based on a biomedical approach [Citation31]. Although the current program worked from a biopsychosocial approach, participants had difficulties comprehending, accepting, and recognizing this approach. To the participants, it felt as though they were not on the same page as their healthcare professionals. The participants often lacked the capacity to negotiate about these differences, which in turn made it difficult to bridge them.

Avoidance in the therapeutic alliance

The high WAI-ReD scores reported by the participants in this study contrasted with the tensions and strains in the therapeutic relationship that were later reported by the participants in the interviews. This discrepancy suggests that participants in pain rehabilitation avoided intimacy as well as disagreement regarding treatment. Earlier research has suggested that avoiding the expression of feelings instead of openly discussing experiences of strains or ruptures in the relationship may be a natural response of participants in healthcare [Citation32]. Moreover, research within psychotherapy has found that strains and ruptures are common in therapeutic relationships, but that both participants and healthcare professionals underreport ruptures due to a lack of awareness or feelings of uncomfortableness [Citation33]. Previous research has emphasized that an unsafe environment and/or an unequal relationship may be a barrier to establishing helpful therapeutic alliance [Citation34]. Participants’ feelings of uncomfortableness in expressing themselves might implicitly indicate that they experienced the rehabilitation program as an unsafe environment for sharing their feelings.

Attachment style regarding avoidance in the therapeutic alliance

The conflict and intimacy avoidance strategies employed by the participants in this study may be partly explained by their attachment history [Citation32,Citation35–37]. Participants in pain rehabilitation programs who had an insecure attachment reported a poorer therapeutic alliance compared with participants who had a secure attachment [Citation38]. Maybe participants with insecure attachment styles have specific needs concerning the therapeutic alliance [Citation39]. As insecure attachment styles frequently occur in participants with persistent pain, the findings of the current study are relevant for pain rehabilitation [Citation40]. However, in a systematic review concerning attachment styles of healthcare professionals evidence was found that also interactions from professionals with participants contributed to quality of therapeutic alliance as well as treatment outcomes [Citation37]. In this study healthcare professionals were not interviewed but more research is required regarding the attachment styles of healthcare professionals and the consequences for therapeutic alliance and treatment outcomes in rehabilitation.

Organizational factors that influence the therapeutic alliance

This study found that organizational factors, such as intake procedures, waiting lists, flexibility of the program, and treatment duration influence the therapeutic alliance. These findings are consistent with earlier studies, which found that organizational and financial factors could have a negative impact on the strength of the therapeutic alliance and collaboration within the alliance [Citation41–43] The protocol of the three screening interviews (Supplementary material 1) was found to be one-sided. In these screening interviews, less attention was paid to the participants’ own definition of their problems, and this lack of attention, in combination with prior experiences, may have contributed to a passive, distanced attitude of the participants. Although the current pain rehabilitation program aims for person-centered care, the organizational and financial aspects might have inadvertently undermined this aim [Citation43].

Implications

This study has several important implications. First, it was found that many participants did not experience a strong therapeutic alliance. Participants were insufficiently aware of the position they held in the alliance and the tasks they could perform therein. Furthermore, they did not feel engaged in the agreement on goals and tasks set forth in the treatment plan. Other studies have shown that a strong therapeutic alliance can contribute considerably to treatment effects [Citation29,Citation30]. This implies that a stronger focus on the therapeutic alliance is needed to improve the effects of pain rehabilitation programs. Healthcare professionals should effectively explore unspoken thoughts, feelings, and dilemmas of participants regarding the therapeutic relationship in combination with the diagnosis and treatment plan. In this way a reciprocal and negotiable relationship with agreement on goals and in tasks can be reached.

A second implication concerns the way ruptures in the therapeutic alliance are addressed. Within psychotherapy, addressing ruptures in the therapeutic alliance is seen as a key component in treatment progress [Citation44]. Solving relational ruptures not only re-establishes the therapeutic alliance, but also functions as an important mechanism for improvement in the health condition of the participant [Citation33]. This implies that it may be beneficial to develop and apply these principles in pain rehabilitation programs. Further research should focus on detecting and solving alliance ruptures in pain rehabilitation programs.

Third, this study shows that the experienced quality of the current therapeutic alliance was negatively affected by previous experiences of fragmented healthcare. Therefore, non-fragmented healthcare, team-based collaboration between healthcare professionals involved in the treatment, and discussions with the participants about the healthcare (treatment-negotiation) are needed to prevent deterioration of the quality of the alliance. The treatment should only start when agreement is reached on problem identification and treatment goals. Better collaboration between healthcare professionals and fewer changes in the members of the healthcare team may strengthen the therapeutic alliance and improve health outcomes [Citation45–47]. Moreover, to achieve this, incorporating relational-therapeutic skills and knowledge of therapeutic alliance as a professional competence in curricula of healthcare professionals may be a prerequisite. Lastly, this study in pain rehabilitation provided in-depth explanations and meanings which may be transferable to other type of multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs.

Study limitations

Three participants voluntarily dropped out of the pain rehabilitation program because they were dissatisfied with its content. They refused an interview despite multiple requests. This non-participation to the interviews may have limited transferability of the results.

Two other limitations were that no interviews were conducted after completion of the rehabilitation program and that the participants were not interviewed for a second time. Participants may experience the therapeutic alliance differently during and after completing the program. Future research should explore how the therapeutic alliance changes over time during the rehabilitation program. An additional limitation of this study was that healthcare professionals were not interviewed. It could be interesting to use dyadic data analysis in this respect, with the participant and healthcare professional forming a dyad. Such an analysis could help in understanding why certain well-meant intentions of healthcare professionals get lost in translation.

Conclusions

In this study on the participant’s perceptions of the therapeutic alliance in a pain rehabilitation, themes were found that obstruct the efficacy of the therapeutic alliance and the treatment plan. These themes were related to painful issues in personal history and context of the participants, impact of intake and waiting-list, inter- and intrapersonal avoidance in the pain rehabilitation program, and experienced complexity in multidisciplinary relationships. In order to improve outcomes, a stronger focus on personalized collaboration from the start of the treatment program is required (dealing with complaints, agreement on diagnosis and treatment plans). During the program, the healthcare professionals should systematically take into account the perceptions and needs of the participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of all participants to this study and also thanks Sonja Hintzen of the University Medical Centre Groningen for her constructive advice and editing service.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, et al. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy. 2018;55(4):316–340.

- Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 1979;16(3):252–260.

- Bordin ES. Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: new directions. New York: John Wiley, Inc.; 1994.

- Safran JD, Newhill CE, Muran JC. Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2003.

- Miller-Bottome M, Talia A, Eubanks CF, et al. Secure in-session attachment predicts rupture resolution: negotiating a secure base. Psychoanal Psychol. 2019;36(2):132–138.

- Babatunde F, MacDermid J, MacIntyre N. Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):375.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The Influence of the Therapist-Patient Relationship on Treatment Outcome in Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1099–1110.

- Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Human technologies in rehabilitation: 'Who' and 'How' we are with our clients. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(22):1907–1911.

- Taccolini Manzoni AC, Bastos de Oliveira NT, Nunes Cabral CM, et al. The role of the therapeutic alliance on pain relief in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34(12):901–915.

- Kinney M, Seider J, Beaty AF, et al. The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;36(8):886–898.

- Crom A, Paap D, Wijma A, et al. Between the lines: A qualitative phenomenological analysis of the therapeutic alliance in pediatric physical therapy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2020;40(1):1–14.

- Bishop M, Kayes N, McPherson K. Understanding the therapeutic alliance in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;43(8):1074–1083.

- Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford)). 2008;47(5):670–678.

- Waterschoot FPC, Dijkstra PU, Hollak N, et al. Dose or content? Effectiveness of pain rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain. 2014;155(1):179–189.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444.

- Besley J, Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Assessing therapeutic relationships in physiotherapy: literature review. New Zeal J Physiother. 2011;39:81–91.

- Danilov A, Danilov A, Barulin A, et al. Interdisciplinary approach to chronic pain management. 2020;132(sup3):5–9.

- Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative research methods. Londen: Sage; 2010.

- Cresswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Los Angeles: Sage; 2012.

- Leedy PD, Ormrod JE, Johnson LR. Practical research: Planning and design. Boston: Pearson Education; 2014.

- McMahon SA, Winch PJ. Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: an essential analysis step in applied qualitative research. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3:1–6.

- Schatman ME, Campbell A. Chronic pain management: guidelines for multidisciplinary program development. Kansas: CRC Press; 2007.

- Schatman ME. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: international perspectives. Pain Clin Updat. 2012;20:1–5.

- Corbin J, Strauss AL, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage; 2015.

- Paap D, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory Dutch version for use in rehabilitation setting. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(12):1292–1303.

- Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, et al. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68(7):438–441.

- Mayer TG, Neblett R, Cohen H, et al. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract. 2012;12(4):276–285.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques. Los Angeles: Sage; 1998.

- Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Flückiger C, et al. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):9–16.

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, et al. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):10–17.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–287.

- Miller-Bottome M, Talia A, Safran JD, et al. Resolving alliance ruptures from an attachment-informed perspective. Psychoanal Psychol. 2018;35(2):175–183.

- Safran JD, Muran JC, Eubanks-Carter C. Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):80–87.

- Fumagalli LP, Radaelli G, Lettieri E, et al. Patient Empowerment and its neighbours: clarifying the boundaries and their mutual relationships. Health Policy. 2015;119(3):384–394..

- Ainsworth MS. Infant–mother attachment. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):932–937.

- Mackie AJ. Attachment theory: its relevance to the therapeutic alliance. Br J Med Psychol. 1981;54(Pt 3):203–212.

- Degnan A, Seymour-Hyde A, Harris A, et al. The role of therapist attachment in alliance and outcome: a systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2016;23(1):47–65.

- Pfeifer A-C, Meredith P, Schröder-Pfeifer P, et al. Effectiveness of an attachment-informed working alliance in interdisciplinary pain therapy. JCM. 2019;8(3):364–381.

- Gillath O, Karantzas GC, Fraley RC. Adult attachment: a concise introduction to theory and research. London: Academic Press; 2016.

- Pfeifer A-C, Gomez Penedo JM, Ehrenthal J, et al. Impact of attachment behavior on the treatment process of chronic pain patients. J Pain Res. 2018;11:2653–2662.

- Mangset M, Dahl TE, Førde R, et al. We’re just sick people, nothing else”: … factors contributing to elderly stroke patients’ satisfaction with rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:825–835.

- Worrall L, Davidson B, Hersh D, et al. The evidence for relationship-centred practice in aphasia rehabilitation. J Interact Res Commun Disord. 2011;1:277–300.

- Lawton M, Haddock G, Conroy P, et al. Therapeutic alliances in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-ethnography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(11):1979–1993.

- Barber JP, Muran JC, McCarthy KS, et al. Research on dynamic therapies. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013.

- Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, et al. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD000072.

- Hardin L, Kilian A, Spykerman K. Competing health care systems and complex patients: An inter-professional collaboration to improve outcomes and reduce health care costs. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2017;7:5–10.

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321.