Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore the patient perspective of their experiences of daily life after spasticity-correcting surgery for disabling upper limb (UL) spasticity after spinal cord injury (SCI) and stroke.

Materials and methods

Eight patients with UL spasticity resulting from SCI (n= 6) or stroke (n= 2) were interviewed 6–9 months after spasticity-correcting surgery. A phenomenographic approach was used to analyze the interviews.

Results

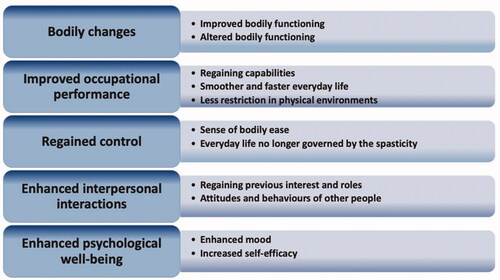

Five themes emerged from the interviews: (1) bodily changes, such as increased muscle strength, range of motion, and reduced muscle-hypertonicity; (2) improved occupational performance, facilitating tasks, mobility, and self-care; (3) regained control, explicating the perception of regaining bodily control and a more adaptable body; (4) enhanced interpersonal interactions, entailing the sense of being more comfortable undertaking social activities and personal interactions; and (5) enhanced psychological well-being, including having more energy, increased self-esteem, and greater happiness after surgery.

Conclusions

The participants experienced improvements in their everyday lives, including body functions, activities, social life, and psychological well-being. The benefits derived from surgery made activities easier, increased occupational performance, allowed patients regain their roles and interpersonal interactions, and enhanced their psychological well-being.

Spasticity-correcting surgery benefits patients by improving bodily functions, which in turn, enable gains in activities, social life, and psychological well-being.

Patients’ experiences of increased body functions, such as enhanced mobility and reduced muscle hypertonicity, appear to increase the sense of bodily control.

The surgery can increase participation and psychological well-being, even for patients whose functional or activity level did not improve after the treatment.

The benefits expressed by the individuals in this study can be used to inform, planning, and in discussion with patients and other healthcare professionals about interventions targeting spasticity.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Spasticity can have detrimental consequences, including loss of mobility and dexterity, contractures, joint deformity, pain, and medical complications such as skin breakdown and infections [Citation1–3]. These factors present challenges in daily life and thereby contribute to decreased independence [Citation1,Citation4] and quality of life [Citation5]. The prevalence of spasticity varies, reflecting differences in the definition of spasticity, the tools used to assess it, and patient selection [Citation6]. Spasticity occurs in 30% of patients after stroke [Citation4,Citation7], and in 80% of patients with spinal cord injuries (SCIs), especially those with cervical lesions or incomplete injuries [Citation8,Citation9]. Spasticity is a major life concern among patients with SCI [Citation10], and it is one of the most frequent secondary conditions in people with disabilities [Citation11]. Disabling spasticity after stroke can increase health-related costs fourfold [Citation12].

Definitions of spasticity have altered over time [Citation13], leading to discrepancies between patients’ and clinicians’ understanding of spasticity and differences in the definitions used [Citation14]. Spasticity is frequently defined as velocity-dependent hypertonia [Citation15], or sustained involuntary activations of muscles that affect body function, activities, or participation [Citation16].

Options for managing spasticity include nonpharmacological treatments, such as muscle stretching, positioning orthoses, and muscle strength training; pharmacological treatments; and surgical interventions [Citation17–19]. Little qualitative research has been done to understand how people with upper limb (UL) spasticity due to a neurological diagnosis experience spasticity treatment. Qualitative studies of patients’ perspectives on living with spasticity have shown complex and diverse effects, ranging from body function impairments to employment and relationship problems, long-term consequences for life goals, and fears for the future [Citation14,Citation20–22]. The varied and individual experience of spasticity suggests that the use of fixed criteria to assess the results of treatment will fail to capture the variety of lived experience, and some perspectives might be missed.

Qualitative studies of interventions for spasticity are rare. Previous qualitative studies have explored relatives’ perspectives on spasticity treatment for children with cerebral palsy [Citation23] and the experience of botulinum toxin treatment among patients with disabling spasticity after stroke [Citation24]. Previous findings show that surgery had beneficial effects for patients with SCI [Citation25] and those with mixed neurological diagnoses [Citation26,Citation27], as judged by improvements in functional and activity-based capacity. To deepen the knowledge of how people with disabling spasticity who undergo spasticity-correcting surgery with tendon lengthening and/or releases (tenotomy) and fractional muscle lengthening experience their everyday life, a qualitative study was conducted to obtain in-depth perspectives of such patients. Doing so would provide a better understanding of the impact of the surgery that would inform clinicians and provide patients with important knowledge for their decision making before undertaking interventions. The aim was to explore patients’ experiences of everyday living after UL spasticity-correcting surgery.

Materials and methods

Study design

Using qualitative research methods, we conducted semi-structured interviews between 1 January 2019 and 31 July 2020. The interviews were analyzed according to a phenomenographic approach [Citation28]. Phenomenography research maps the qualitatively different ways in which people experience, conceptualize, perceive, and understand a phenomenon. Since the aim was to collect a variety and broad range of experiences from a specific phenomenon, this approach was considered suitable [Citation28]. Conception is a central concept in phenomenographic research, and the most essential outcome is descriptions of differences and similarities in the patients’ conceptions of a phenomenon [Citation28].

Intervention

The patients were treated according to a structured protocol that allocated patients to a high-, low-, or non-functioning regimen (HFR, LFR, NFR) [Citation25–27]. The patients included in the present study were allocated to the HFR and the LFR. In the HFR, the goal of surgery is to improve volitional muscle control and thereby enable use of the affected arm in unimanual activities. In the LFR, the goal is to improve the use of the affected arm in bimanual UL activities. Inclusion criteria and content in the different regimens have previously been presented in detail [Citation27]. The surgical techniques and rehabilitation are briefly described in Appendix 1.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with UL spasticity who underwent surgery at the Centre for Advanced Reconstruction of Extremities at Sahlgrenska University Hospital were eligible for the study. The inclusion criteria were (1) ability to communicate in Swedish; (2) velocity-dependent hypertonicity or sustained involuntary activations of muscles as the primary component of spasticity; (3) spasticity-correcting surgery including at least lengthening or release of two UL muscle tendons; (4) some residual volitional motor control in the spastic UL enabling active range of motion; and (5) preoperative expectation of gains in uni- or bimanual activities in daily life or increased supportive use of the treated arm in activities. Patients were excluded if they had a postoperative injury or sickness such as fractures, cancer, or syringomyelia that affected performance in everyday life.

Data collection

An interview guide was developed by the primary researcher (TR) in consultation with the research group. As proposed by the method, the guide was not used as a strict checklist. The interview started with standard questions about each participant’s background. The opening interview question was “Can you describe your experiences in everyday life after the treatment with spasticity-correcting surgery and subsequent rehabilitation?” Additional questions mainly focused on their experiences, thoughts, and feelings about the impact of the treatment on daily life. The patients were invited to participate either in person during their planned 3-week postoperative inpatient stay or by mail or email after discharge.

The interview site was chosen together with the participant. Five interviews were conducted in a private room in the rehabilitation clinic nearest the patients’ homes’, and three were conducted at the patients’ homes’ via a digital meeting tool. All interviews were conducted one-on-one by the primary researcher – a PhD student with 20 years of clinical experience working as an occupational therapist in neurological rehabilitation. The interviews’ mean duration was 24 min (range: 15–42 min). All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by the primary researcher. Field notes made during the interviews were discussed with the participants afterward to verify the content of the key message. All interviews were completed before the analyses were initiated.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed according to the phenomenographic approach in four steps [Citation29]. First, verbatim transcripts of the interviews were read thoroughly several times to obtain an overall impression of the material. Second, similarities and differences in the material were noted. According to the phenomenographic approach, saturation is achieved when no new interpretations are found in the material. Third, similarities and differences were classified in order to generate an initial set of categories. These categories are called the outcome space in the phenomenographic approach. Fourth, the categories were reflected upon to identify themes describing participants’ experiences of how the treatment affected their daily life. The transcript was coded first by the primary researcher, who had theoretical experience and some practical experience with qualitative research. In order to enable discussion of the results and to prevent the findings from representing a researcher’s preconceived ideas, a parallel analysis was done. A co-examiner (JW) reviewed the similarities and differences identified by the primary examiner and created categories that were compared with those of the primary researcher. Similarities and differences were discussed first by the co-examiners and then by all authors; the final themes and categories were established by consensus. Both JW and LB-K are experienced qualitative researchers. The final categories were presented to an external independent examiner experienced in qualitative methodology who was not involved in the study. The examiner was asked to assign the quotations to the “correct category”. Agreement was 77%. NVivo (version 12.2) was used for the statistical analysis.

Trustworthiness

The COREQ criteria for reporting qualitative research were used [Citation30]. As with qualitative research in general, it should be possible to follow the researchers’ thinking throughout the study. To obtain a high level of trustworthiness, the categories must be sound and represent the perceptions of the participants and not simply those of the researcher [Citation29,Citation31,Citation32]. Credibility was taken into account by including a heterogeneous group of patients with the aim of sampling a rich variety of experiences. After the interviews, the field notes were discussed with the participants to check for accuracy. To ensure transferability, the participants’ characteristics are described as well as surgical treatment and the data collection and analysis procedures. To help readers evaluate the trustworthiness of the analysis, quotes from the interviews are given for each category.

Ethics

The participants received both written and oral information about the study. Before the interviews, all participants signed informed consent forms. To protect anonymity, personal details were removed from the interview transcripts. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr: 535-18).

Results

Between June 2018 and March 2020, a total of 33 individuals underwent spasticity-correcting surgeries in the UL. Of those, 15 individuals were not eligible since no gains as a result of surgery could be expected in terms of uni- or bimanual activities in daily life or increased supportive use of the treated arm. Six were excluded due to cognitive difficulties that hindered reflection upon the intervention’s effect, and four individuals were excluded due to language difficulties. Eight patients were thus eligible and accepted to participate in the study. In six patients, spasticity was due to SCI; three had bilateral UL impairment, and three had incomplete unilateral injuries. The remaining two patients had unilateral spastic hemiplegia due to stroke. The mean age of the patients was 62 years (range 49–78 years). The mean time since injury was eight years (range 1–18 years). In four cases, the goal of surgery was to improve volitional muscle control and thereby enable use of the affected arm in unimanual activities. In the remaining four cases, the goal was to improve use of the affected arm in bimanual UL activities. The type of ambulation reported by patients were wheelchair (n = 4) and walking (n = 4). The participants were geographically dispersed all over Sweden. The interviews took place at a mean of 7.6 months after the surgery (range 6–9 months) ( and ).

Table 1. Characteristics of the interviewed participants.

Table 2. Diagnosis, type of injury, and target muscles.

Five themes emerged from our analysis of the interviews: (1) bodily changes, (2) improved occupational performance, (3) regained control, (4) enhanced interpersonal interactions, and (5) enhanced psychological well-being. Each theme is represented by two to three categories, each demonstrating a particular aspect of the theme ().

Theme 1: bodily changes

The first theme covers the participants’ perspectives on how their bodies had changed after the treatment. All participants described bodily changes, most of which were positive. This theme has two categories: (1) improved bodily functioning and (2) altered bodily functioning.

Improved bodily functioning

All participants noted improvements in bodily functions, such as improved muscle strength, flexibility, reduced tone, and increased range of motion. Some commented that their posture had improved, enabling them to move more easily, and some also noted reduced spasticity-related pain after the surgery. Participant 2 (a 58-year-old man) said:

I had a constant sensation of tension and pulling in the hand. Now I can open the hand and let go of stuff.

Participant 6 (a 68-year-old man), commented:

Yes mobility and a little more strength. The body has become softer.

Altered bodily functioning

Some participants noted an initial reduction in hand strength, which they perceived as worrisome. During a 3-week restriction period when a splint had to be worn 24 h per day, some said they could not be as active as they used to be or engage in their regular exercise regimen, resulting in reduced strength of the UL. The initial postoperative weakness required behavioral changes by the participants to continue with their regular activities of daily living. In the words of participant 1 (a 74-year-old man):

I had to modify some exercises and do what I could do, and some exercises I did not get done, which was restrictive for me and made me weaker. And it was very hard. I had the splint on the right hand, the operated one, and I could not hold the walker with that hand. And the left hand was also affected in a way, which was challenging, but I learned to live with it. It was the most difficult time—the two-three weeks or whatever it was when the splint was on 24 hours a day.

Participant 2 (a 58-year-old man) said:

I could not separate the spasticity from my own strength before the surgical procedure. That was the difficult part for me after having undergone the surgery—that I was so very weak in the hand. I got a little nervous and thought, How do I manage now?

Theme 2: improved occupational performance

The second theme covers the participants’ perceptions of how the surgery changed their capabilities and ways of engaging in certain activities and occupations. The participants noted that postoperative functional improvements led to gains in activities of daily life, including both general tasks and demands, and in mobility and self-care. Some participants noted increased activity levels soon after surgery, whereas others felt that it took time for the increased physical capabilities to lead to better performance of daily tasks. This theme consists of three categories: (1) regaining capabilities, (2) smoother and faster everyday life, and (3) less restriction in physical environments.

Regaining capabilities

All participants had increased ability to grasp, lift, and carry different objects after the surgery. Many noted greater independence in certain activities, such as eating with a knife and fork and being able to cut food into pieces, brushing their teeth, and grasping a glass. Some participants described being able to use the treated hand for unimanual activities or as a supporting hand in bimanual activities, such as slicing bread and opening bottles. Those who could undertake bimanual activities after surgery experienced greater independence. Many participants experienced satisfaction in being able to do things independently. Some noted that functional gains that would be considered minor for a healthy person were nevertheless important because they enabled greater independence. Participant 1 (a 74-year-old man) commented:

Before the surgery I could not hold cutlery, for example when I’m eating, which I am able to do today. And I could not move glasses cups and stuff, which I can do today.

Participant 8 (a 65-year-old man) noted:

The best thing, the absolute best thing with my hands, is that I can grasp a regular walker. I can grasp the handles and hold on to them while walking, for example on the property.

Quite a few participants experienced gains in bimanual activities, since the treated arm had improved enough to be used for support in activities such as washing, dressing, caring for the treated arm, cutting bread, and opening bottles. Participant 4 (a 49-year-old man) said about his affected hand:

It works as a support hand, because I can now rotate the palm upwards. I can place bottles and stuff in the hand.

Participant 4 (a 58-year-old woman) commented:

Yes I’m thinking about cutting stuff. I’ve thought about it a lot now and it’s something I can do now. Before I squeezed the bread with my clenched hand, but now I surely think I manage.

Many participants mentioned increased ability to engage in household activities, such as gardening, meal preparation, cooking, and shopping. Participant 1 (74-year-old man) said:

Open packages or when sitting and changing batteries in my remote controls and such stuff, I can do that myself now. I could not before.

Participant 3 (65-year-old woman) said:

I do some gardening, cut bushes and stuff, sit outside and pull weeds.

Smoother and faster everyday life

Some participants described positive changes in their everyday life, as many activities that were difficult or even impossible before the surgery became less problematic, which made everyday life easier and smoother. They also described scenarios that involved both upper and lower extremities. For instance, some participants reported that transfers and walking were easier, as the arm and hand functioned better. Participant 5 (49-year-old man) said:

My walking has improved.

Others described how UL activities were improved, and how some activities had become much easier to perform. For example, participant 2 (58-year-old man) said:

I do almost anything that requires letting go of things. Before, I had to pull it out of my hand. Now I can open my hand and drop things.

Participant 7 (60-year-old man) commented:

Easier to put on a jacket and remove it now when the arm is more flexible.

The participants also noted that many activities were less time-consuming. Describing his ability to release objects, participant 2 (58-year-old man) said:

Before it was more complicated. Now it is easier and faster to do similar things as before.

Less restriction in physical environments

Some participants felt less restricted by their physical surroundings. Before the surgery, secure access required environmental modifications. Their new ability to use another walking aid increased their ability to access public transportation, enabling alternative ways of traveling. As participant 8 (65-year-old man) said:

I can visit my neighbours. I have surprised them now. I had not visited them before because I needed assistance. The power chair was too clumsy, but it works fine now when I use a walker.

Theme 3: regained control

The third theme covers participants’ experiences of regaining control. Before surgery, they perceived their spasticity as being in charge of their body, determining which activities they chose to undertake. After the treatment, several participants noted that they themselves were in charge of their bodies and activities, not the spasticity. Many participants also highlighted the greater adaptability of their bodies after the surgery. This theme includes two categories: (1) sense of bodily ease and (2) everyday life no longer governed by the spasticity.

Sense of bodily ease

Many participants commented that the most important change was their perception that their body was more adaptable after the treatment. This aspect does not reflect on the regained capabilities or improved bodily functioning after the treatment, but rather that reduced spasticity led to a sense of ease and that daily activity performance became less of a hassle. Participant 7 (a 60-year-old man) said:

As I have now painted the porch, and it works really well now to stand and paint with the unaffected hand, since the affected hand remains still without spreading the paint around on the wall.

Participant 4 (58-year-old woman) commented:

It surely affects my whole life, that the body does not call for attention as much as before by being so damn pulling, but now the body is a bit more normal.

Everyday life no longer governed by spasticity

Several participants commented on their sense of regained control over both their body and their daily schedule, which was no longer restricted by spasticity. Participant 7 (a 60-year-old man) said:

Now I dare to walk next to another person without bumping into them. Before, I had to hold on to the affected arm and keep it close to the body, because when the spasm came the arm could drag someone along.

Participant 4 (a 58-year-old woman) said:

The body is no longer so unpredictable, that totally weird thing when it just went away and did strange things or was just tense. It’s probably more controllable now.

Theme 4: enhanced interpersonal interactions

The fourth theme covers the participants’ experiences of changes in their interactions with others. One aspect of this theme was that the treatment-induced gains in physical abilities enabled greater participation in social activities with family members or peers. Another aspect was the reduced misalignment of the UL after surgery, an improvement in appearance that enabled some participants to feel more comfortable participating in social interactions. They perceived they were no longer judged by the look of their disabled UL. The categories in this theme are (1) regaining previous interests and roles and (2) attitudes and behaviors of other people.

Regaining previous interests and roles

The participants felt they had more energy to participate in leisure activities, enabling them to regain some of their previous roles. For some participants, being less dependent increased their ability to devote time to leisure activities. Before the surgery, some said, their children had to assist them in their daily life, whereas afterward they could do a lot more by themselves and thus they regained the parent–child relationship to a certain extent. As participant 3 (a 65-year-old woman) put it:

Before, my daughter used to help me. Nowadays she does not need to and is not allowed to either. She has her own family and children. She should not come to me and clean. Now I do it myself, and we can spend our time doing other things, like going for coffee and shopping, so it works great.

Many participants also noted that they had resumed some of their previous leisure pursuits, such as gardening, crafts, and cultural activities. Participant 2 (a 58-year old man) said:

Write with a pen, do crosswords, and that kind of things I can do now. It keeps the brain active.

Attitudes and behaviors of other people

Many participants noted the stigmatization that a spastic UL entails. For example, people may not know how to act when shaking hands with a person with UL spasticity. The surgery brought about positive changes in the attitudes and behaviors of other people. Participant 1 (a 74-year-old man) put it this way:

It sure does look nicer, it does, when the hand is not clenched. When people reach out the hand to do a handshake, they do it in the right way…. It looks nicer when the hand is half-opened, as compared to when it was completely stiff and clenched.

Participant 5 (a 49-year-old man), said:

That the arm and especially the hand shiver less. It feels good when meeting other people. They look at me less than before.

Theme 5: enhanced psychological well-being

Improved psychological functioning was identified as a theme, which participants described as feeling more energetic, having greater self-esteem, more self-confidence, and a happier mood, feeling less frustrated, and having greater mental strength and improved confidence. The theme has two categories: (1) enhanced mood and (2) increased self-efficacy.

Enhanced mood

Many participants noted that they felt happier, less frustrated, and generally more at ease. Some noticed the improvement in their mood themselves, whereas others were told by family members or relatives. Participant 1 (a 74-year-old man) said:

I simply get in a better mood. These little annoyances, when you think, damn, I cannot do this, that everything should be so difficult. I no longer think that way because now I can do it. In that way it has become better.

Participant 7 (a 60-year-old man) simply said:

I feel better.

Some participants thought the improvement in mood was linked to treatment-induced gains in activity performance, whereas others noted that the spastic UL felt softer, alleviating the previous stiffness that had caused substantial frustration. In the words of participant 3 (a 65-year-old woman):

You do feel better about yourself than if you need help from others. That is what I think.

Increased self-efficacy

Several participants reported feeling more confident and secure after surgery. Enhanced self-esteem made participants more likely to increase both their participation and performance in activities after the treatment. They felt they could better challenge themselves, noting that greater success in carrying out activities in turn further increased their confidence. According to participant 8 (a 65-year-old man):

One dares to do more things now than before, even though I consider safety aspects. I’m now able to lift things and work with my hands in a different way. I can build mental strength also by approaching the achievability of things I didn’t do before. Having an independent life and so on is an important goal for me.

Participant 4 (a 58-year-old woman) put it this way:

It could be because I’m more confident with my body, I trust my body more.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that describes patients’ experiences of spasticity-correcting surgery and its impact on daily life. Five themes emerged from our analysis, all of which describe the participants’ conception of how the treatment brought about changes in their daily life. The chosen analysis method, phenomenography, aiming to explore the different ways people experience a phenomenon in order to capture a holistic view [Citation29,Citation33]. In phenomenography, the participants need to have experienced the phenomenon themselves [Citation29,Citation33]. The main approach is to highlight the “second-order perspective”, which asks how people experience a phenomenon, whereas “first-order perspective” asks what the phenomenon is [Citation29,Citation33]. The aim with phenomenography conforms with the aim of the present study. The different categories that emerge represent different ways to perceive a phenomenon form an “outcome space”, the outcome space being a holistic picture of how different conceptions relate to each other. The relation can be hierarchical or linear [Citation29]; the results in this study are linear but some hierarchical tendencies are presented. For example, all participants in the present study highlighted in particular the perceived bodily changes as the foremost result of their surgery. Beneficial gains such as having a more adaptable body, regaining previous interests and roles, enhanced mood and changes in the attitudes and behaviors of others could be ascribed to the participants’ improved bodily functioning and the regained capabilities. All participants believed the treatment had been beneficial.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is a classification system with an overall goal of creating a unified and standardized language and structure to describe health and health-related conditions [Citation34]. The perceived beneficial gains could be ascribed to the different domains of the ICF and are consistent with the range of experiences previously described by affected individuals [Citation14,Citation20–22,Citation24]. The variety of experiences most likely reflect the heterogeneity of the participants, who differed in the type and severity of injury (SCI and stroke) and consequently in the degree of spasticity and the resulting unimanual or bimanual impairment. These factors contributed to a wide range of conceptions, not all of which were applicable to the study population as a whole. This heterogeneity mirrors the various types and degrees of disabling spasticity caused by central nervous system injuries. Hence, the experiences of our patients may be representative of those of community-dwelling individuals tackling the consequences of UL spasticity.

Most of the conceptions revealed during the interviews were positive. However, one negative conception was the experience of initial weakness due to tendon lengthening and reduced activity level due to the splint, which had to be worn day and night after the surgery. This finding adds to the empirical knowledge base and highlights the importance of informing all patients before surgery about reduced muscle strength and its consequences in daily life. Another challenge for some participants was the need to relearn certain skills because of functional changes.

The positive conceptions mentioned by the participants cover a wide range of daily situations. The participants described gains in physical function after the surgery, such as improvements in range of motion, muscle strength, and grasp ability, as well as reduced muscle tone and less pain. These findings are in line with those of an observational study [Citation26]. Increased range of motion and decreased muscle tone are also commonly reported beneficial effects of botulinum injections [Citation35] and surgical interventions [Citation27,Citation36–38]. In the present study, improvement in range of motion and muscle tone was the first beneficial effect experienced by all participants. These gains were also reflected in comments that the UL was softer and contributed to increased mobility and beneficial postural changes. The participants mentioned various ways in which these improvements contributed to behavioral changes in their everyday life.

According to participants who were not dependent on walking aids, the improvements in UL function and joint positioning increased their walking capacity. Participants who used walking aids said they could more easily hold on to the aid, which they felt increased their walking capacity. This ameliorating effect was described after treatment of UL with botulinum toxin [Citation39,Citation40] and surgery [Citation41]. Moreover, the participants also noted a generally improved posture when standing, sitting, and lying down.

Our study included participants with different diagnoses, wheelchair users, walkers and both good and poor volitional muscle control. The cohort consisted mainly of participants with spasticity problems due to SCI (75%). In line with our clinical experience, previous findings [Citation27] suggest that the amount of residual volitional control prior to surgery is more indicative of what outcome to expect, rather than diagnosis and type of ambulation. Since sub-analyses are commonly not included in qualitative research, we cannot differentiate between factors such as diagnoses in the present study. Those with unimanual spasticity noted that they could carry out bimanual activities that were difficult or even impossible before surgery. Those with bimanual spasticity recounted that they could do some unimanual activities but were still restricted by the impaired arm when performing bimanual activities. Importantly, participants in both groups, especially those with poor muscle control (LFR), experienced a sense of regained bodily control and less daily hassle, which in turn led to enhanced mood, self-esteem, and participation. They did not have to think so much about their arm anymore and noted that it caused fewer problems. For some, these positive effects improved their energy levels, sleep quality, and sense of freedom. For others, the positive psychological impact came from the improved appearance of the spastic limb, reducing the stigma of a rigid flexed position of the elbow, wrist, or fingers. These changes were appreciated by the participants because they were concerned about their own appearance, as well as the conception of others. The positive aesthetic and physical effects, participants reported, enabled them to feel a little more at ease in their physical and social environments. Previous reports have shown that individuals with spasticity experience a lack of understanding about spasticity by the public, a feeling of social stigmatization, social embarrassment, and that other people do not like touching them, such as when shaking hands [Citation14,Citation20].

Some of the experienced gains reported by the patients in this study are in line with previous findings in observational studies on surgical interventions targeting spasticity, namely, increased range of motion and decreased muscle tone and pain [Citation36,Citation42]. Ease of care and aesthetic gains are other commonly reported gains after surgical interventions [Citation37,Citation43]. In this study, the expressed gains go beyond the previously reported gains relating to increased physical capacity and ease of care. The participants expressed that the beneficial effects of surgery affected their mood in a positive way and expressed enhanced self-confidence and self-esteem, which have not previously been reported. These perceptions are likely to be of value for participants given that the disorder is shown to bring about psychological distress, negative emotions, social isolation, and negative economic impact [Citation14,Citation20]. Likewise, since previous studies highlight the detrimental effects of spasticity on activity performance and participation [Citation14,Citation20], the increased activity performance and participation reported by patients in the present study are likely to be a significant finding. These findings may be difficult to capture by observer-based measures. Compared to observer-based measures, qualitative methodological approaches enable identification of gains in complex activities and participation. Measures such as the Spinal Cord Injury Spasticity Evaluation Tool (SCI-SET) [Citation44], which assesses feelings of control over the body, and the Patient-Reported Impact of Spasticity Measure (PRISM) [Citation45], which assesses the social and psychological impact of interventions, could be used to capture more fully a patient’s experience of the treatment and their increased capabilities. The use of patient reported outcomes (PROMS) is recommended in both research and clinical work and are essential to understand the patient’s experience. The use of PROMS, like SCI-SET and PRISM, would provide a more holistic view of the patient and could be useful in future research to deepen the understanding of interventions targeting spasticity.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the participants were recruited from a single center, which could affect the generalizability of findings. However, the context is well described in the appendix and in previous studies, increasing the possibility of assessing the transferability to other settings. Second, the researchers in this study contributed to the initial clinical care of the patients. As a result, some participants might not have mentioned negative aspects of their experiences; alternatively, they might have had greater trust and have been more likely to share their experiences, knowing that the information could more easily be implemented in the clinic. This “dual role” bias was limited by having an independent researcher assign quotations to the identified categories to increase trustworthiness. Third, the time elapsed since surgery was six to nine months, based on previous reports of gains in daily life six months after surgery [Citation25–27]. A later timepoint could possibly have resulted in patients having difficulties in reflecting on their past experiences. Nonetheless, there is a need to conduct observational studies investigating the long-term effectiveness of spasticity-correcting surgery. Finally, since we studied only eight patients with UL spasticity due to SCI or stroke, caution should be used in generalizing our results to other populations. The choice to terminate the inclusion at eight patients was due to the COVID pandemic, which started in 2020 and caused all surgeries to be put on hold. As the included patients varied in diagnosis, gender, and assigned regimen, variations in their experiences were expected and therefore the termination of inclusion felt justified. Although the intention of qualitative research is not to provide generalizable data but to report the conceptions and experiences of the participants, our results are consistent with our clinical experience and observational findings [Citation26]. Thus, our results are likely to be relevant to populations similar to the participants in this study.

Conclusions

The study participants’ conceptions about the beneficial effects of spasticity-correcting surgery on everyday life included improved bodily functions and occupational performance, a sense of bodily ease and that daily activity performance became less of a hassle because of regained bodily control. Other positive conceptions were that participants could return to previous social roles and that beneficial effects of surgery brought about enhanced psychological well-being. The effects were mainly positive. A negative effect that emerged was the initial weakness and its impact on everyday life. All participants described experiences of increased passive or active range of motion and reduced tone. One of the most interesting findings was the perceived increase in control of the body, which led to increased participation and greater psychological well-being, even for participants with minimal gains in function or activity level. These conceptions can be used to facilitate goal-setting in discussions between future patients and health care professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams MM, Hicks AL. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(10):577–586.

- Meijer R, Wolswijk A, Eijsden H. Prevalence, impact and treatment of spasticity in nursing home patients with central nervous system disorders: a cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(4):363–371.

- Barnes M, Kocer S, Murie Fernandez M, et al. An international survey of patients living with spasticity. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(14):1428–1434.

- Zorowitz DR, Gillard JP, Brainin JM. Poststroke spasticity: sequelae and burden on stroke survivors and caregivers. Neurology. 2013;80(3 Suppl. 2):S45–S52.

- Milinis K, Young CA, Trajectories of Outcome in Neurological Conditions (TONiC) Study. Systematic review of the influence of spasticity on quality of life in adults with chronic neurological conditions. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(15):1431–1441.

- McGuire JR. Epidemiology of spasticity in the adult and child. In: Brashear A, Elovic E, editors. Spasticity: diagnosis and management. New York: Demos; 2016.

- Thibaut A, Chatelle C, Ziegler E, et al. Spasticity after stroke: physiology, assessment and treatment. Brain Inj. 2013;27(10):1093–1105.

- Holtz KA, Lipson R, Noonan VK, et al. Prevalence and effect of problematic spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(6):1132–1138.

- Maynard FM, Karunas RS, Waring WP 3rd. Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71(8):566–569.

- Hart KA, Rintala DH, Fuhrer MJ. Educational interests of individuals with spinal cord injury living in the community: medical, sexuality, and wellness topics. Rehabil Nurs. 1996;21(2):82–90.

- Moharić M. Research on prevalence of secondary conditions in individuals with disabilities: an overview. Int J Rehabil Res. 2017;40(4):297–302.

- LundströM E, Smits A, Borg JRGEN, et al. Four-fold increase in direct costs of stroke survivors with spasticity compared with stroke survivors without spasticity: the first year after the event. Stroke. 2010;41(2):319–324.

- Malhotra S, Pandyan AD, Day CR, et al. Spasticity, an impairment that is poorly defined and poorly measured. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(7):651–658.

- Bhimani RH, McAlpine CP, Henly SJ. Understanding spasticity from patients' perspectives over time. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(11):2504–2514.

- Lance JW. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg lecture. Neurology. 1980;30(12):1303–1313.

- Pandyan A, Gregoric M, Barnes M, et al. Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(1–2):2–6.

- Richardson D. Physical therapy in spasticity. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9(Suppl. 1):17–22.

- Sunnerhagen SK, Olver EJ, Francisco EG. Assessing and treating functional impairment in poststroke spasticity. Neurology. 2013;80(3 Suppl. 2):S35–S44.

- Rekand T. Clinical assessment and management of spasticity: a review. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2010;190(190):62–66.

- Mahoney JS, Engebretson JC, Cook KF, et al. Spasticity experience domains in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(3):287–294.

- Morley A, Tod A, Cramp M, et al. The meaning of spasticity to people with multiple sclerosis: what can health professionals learn? Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(15):1284–1292.

- Bhimani R, Anderson L. Clinical understanding of spasticity: implications for practice. Rehabil Res Pract. 2014;2014:279175.

- Nguyen L, Di Rezze B, Mesterman R, et al. Effects of botulinum toxin treatment in nonambulatory children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: understanding parents' perspectives. J Child Neurol. 2018;33(11):724–733.

- Kerstens HCJW, Satink T, Nijkrake MJ, et al. Experienced consequences of spasticity and effects of botulinum toxin injections: a qualitative study amongst patients with disabling spasticity after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;1–8.

- Wangdell J, Fridén J. Rehabilitation after spasticity-correcting upper limb surgery in tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):136–143.

- Bergfeldt U, Stromberg J, Ramstrom T, et al. Functional outcomes of spasticity-reducing surgery and rehabilitation at 1-year follow-up in 30 patients. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45(8):807–812.

- Ramström T, Bunketorp-Käll L, Reinholdt C, et al. A treatment algorithm for spasticity-correcting surgery in patients with disabling spasticity: a feasibility study. J Surg. 2021;6:1363.

- Marton F. Phenomenography—a research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. J Thought. 1986;21(3):28–49.

- Alexandersson M. Den fenomenografiska forskningsansatsens fokus (the phenomenographic research approach in focus). In: Starrin B, Svensson P-G, editors. Kvalitativ metod och vetenskapsteori (qualitative method and scientific theory). Lund: Studentlitterattur; 1994.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2017.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2009.

- Marton F. Phenomenography — describing conceptions of the world around us. Instruct Sci. 1981;10(2):177–200.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Andringa A, van de Port I, van Wegen E, et al. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin treatment for upper limb spasticity poststroke over different ICF domains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(9):1703–1725.

- Tafti MA, Cramer SC, Gupta R. Orthopaedic management of the upper extremity of stroke patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(8):462–470.

- Gatin L, Schnitzler A, Calé F, et al. Soft tissue surgery for adults with nonfunctional, spastic hands following central nervous system lesions: a retrospective study. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(12):1035–1035.

- Gras M, Leclercq C. Spasticity and hyperselective neurectomy in the upper limb. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2017;36(6):391–401.

- Hirsch MA, Westhoff B, Toole T, et al. Association between botulinum toxin injection into the arm and changes in gait in adults after stroke. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):1014–1020.

- Bakheit A, Sawyer J. The effects of botulinum toxin treatment on associated reactions of the upper limb on hemiplegic gait—a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(10):519–522.

- AlHakeem N, Ouellette EA, Travascio F, et al. Surgical intervention for spastic upper extremity improves lower extremity kinematics in spastic adults: a collection of case studies. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;21(8):116.

- Tranchida GV, Van Heest A. Preferred options and evidence for upper limb surgery for spasticity in cerebral palsy, stroke, and brain injury. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45(1):34–42.

- Gschwind CR, Yeomans JL, Smith BJ. Upper limb surgery for severe spasticity after acquired brain injury improves ease of care. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2019;44(9):898–904.

- Adams MM, Ginis KA, Hicks AL. The spinal cord injury spasticity evaluation tool: development and evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(9):1185–1192.

- Cook KF, Teal CR, Engebretson JC, et al. Development and validation of patient reported impact of spasticity measure (PRISM). J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(3):363–371.

Appendix 1.

Description of the treatment

The surgical procedures used in this study population were tendon lengthening and releases (tenotomy) and fractional muscle lengthening. Lengthening of a tendon or releasing a muscle from its insertion relaxes the whole muscle-tendon unit. Hence, the spasticity is alleviated but not eliminated. The tendon lengthening procedure consisted of a stair-step incision and reattachment in the lengthened position with a side-to-side, cross-stich technique. The day after surgery, wrappings and custom-made orthoses were fashioned to facilitate prolonged soft tissue stretch and prevent postoperative edema. For the first 3 weeks, the orthosis was worn at all times to provide additional stretch, except during training sessions. When possible, active dynamic activation of the antagonist muscles of the lengthened muscles was done on the day after surgery, along with passive or dynamic activation of the lengthened muscles.

As a result of the surgical lengthening, the treated muscle was commonly weakened, which increases the patient’s potential to voluntarily recruit the antagonists to the spastic muscles. Therefore, even though closing of the hand was weakened, training of the finger extensors was prioritized at this point. Early active mobilization was done to reduce the risk of adhesions, joint stiffness, and muscle weakness. Before discharge, patients were taught a personalized home training program, to be done 2–4 times daily either independently or with assistance from career/relatives. Patients were also trained and encouraged to frequently use the hand (with the orthoses on) in daily activities to maintain muscle fitness and prevent edema by using the muscle pump. The postoperative treatment and length of stay varied depending on the regimen.

Three weeks after surgery, all patients returned to the ward for follow-up and inpatient rehabilitation of varying length. From then on, training in daily activities and motor control was added to the functional training, along with development of functional resting positions. Orthoses were now only worn at night time, until at least 3 months after surgery. The orthosis was re-adjusted if needed for optimal fit and further stretching. The continued training of functions and activities was individually tailored to meet the goals of each patient.