Abstract

Purpose

A rights perspective proposes supported decision-making as an alternative to substitute decision-making. However, evidence about supported decision-making practice is limited. Our aim was to build evidence about building the capacity of decision supporters.

Methods

Eighteen parents of people with intellectual disabilities were trained in decision support using the La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework. Data from repeated semi-structured interviews and mentoring sessions were used to capture parental reflections on the value of training.

Results

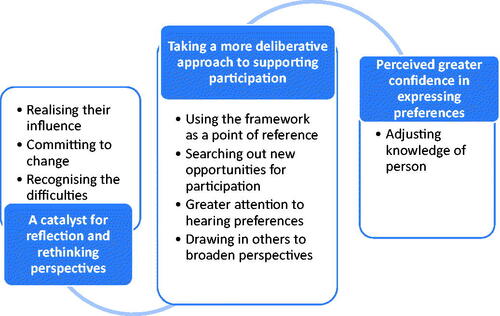

The training acted as a catalyst for parent self-reflection and the Framework prompted them to adopt a more deliberative approach to supporting decision-making. Some parents perceived increased confidence of their adult offspring in expressing preferences resulting from their own changed approach.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the efficacy of this Framework and evidence-based training in building the capacity of parental decision supporters to be consistent with the rights paradigm.

The La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework is an evidence-based approach to decision support practice with an accompanying set of free online resources which can be used by individual practitioners or programs to inform their practice and build the capacity of supporters.

Parents of adults with intellectual disabilities value training in the La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework, which they consider helps to develop their decision support skills and self-reflection.

Parents also value individual mentoring following training to assist them to apply the principles of the practice framework to the everyday support for decision-making they provide to their adult son or daughter.

Training in support practice should be accompanied by individual mentoring or other strategies to assist parents of adults with intellectual disabilities to discuss and solve the difficult issues they confront in providing decision support more aligned to the rights paradigm.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) has generated changed thinking about decision-making for people with intellectual disabilities. Article 12 of the CRPD has been interpreted as requiring “the ‘will and preferences’ paradigm to replace the “best interests” paradigm to ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy the right to legal capacity on an equal basis with others” [Citation1,p.5]. Such interpretations propose supported decision-making options should replace substitute decision-making regimes [Citation2]. The underpinning principles of such options are respect for the person’s right to participate in decision-making, support that gives primacy to their will and preferences, and mechanisms that safeguard against undue influence by supporters [Citation3].

In Australia, as in other jurisdictions, law reform agencies have reviewed the rationale for supported decision-making options (for review see Then et al. [Citation4]). Many have recommended new schemes as alternatives rather than replacements for substitute decision-making laws. However, legal reform has been slow. A common concern raised by law reform agencies has been the scant evidence about the support practices necessary to deliver rights-based support as well as concerns about potential abuse of supporters’ power [Citation5].

Evidence about supported decision-making practice is slowly growing. For example, Browning’s [Citation6] study of 25 decision supporters of people with intellectual disabilities in the context of Representation Agreements in British Columbia, Canada, found their support varied in its respect for a person’s preferences. This variability was mediated by the type of a decision, the context, the values of both supporters and the person, and their relationship. Supporters perceived the benefits of Representation Agreements as practical, such as recognition of their standing by third parties, and few had been offered training in supported decision-making principles. Various small pilot projects, in Australia and elsewhere have trialled models for delivering support aligned with the intent of supported decision-making outside legislated schemes [Citation7,Citation8]. Evaluations of pilots have been positive but point to limited evidence underpinning training for supporters and the frequent exclusion of people with more severe intellectual disabilities or those without existing supporters from schemes. Although evaluations of support practice are limited, findings do suggest the value of training and supervision for supporters.

Notably, similar variability in support practices to those found by Browning [Citation6,Citation9] has been identified by studies of decision support outside the context of formally supported decision-making schemes [Citation10–13]. These studies suggest supporters’ respect for preferences varies depending on the decision and context, and their actions can range from controlling to enabling. Empirical findings such as these add to the previous commentary by Carney [Citation14] about the importance of focussing on the capacity of decision supporters to deliver support that facilitates participation and respect for will and preferences both within and outside formal supported decision-making options.

Finding ways to build supporter capacity and progress the shift to a rights paradigm has posed a major policy challenge in Australia. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was intended to reflect aspects of the government’s CRPD obligations and increase the choice and control of people with disabilities through reform of the disability system [Citation15]. However, despite adults with intellectual disabilities being the largest single group of adult participants in the NDIS, it does not incorporate features to ensure availability of decision-making support, build supporters’ capacity to respect will and preferences, or ensure accountability of supporters. Rather the NDIS relies on existing unregulated informal support or appointment of substitute decision-makers through its nominee provisions or guardianship laws in each State or Territory [Citation16]. Six years since its inception the implications of these omissions from the NDIS are becoming clear: growing numbers of people with intellectual disabilities are losing their right to legal capacity as appointments of guardians increases, and evidence is accumulating about their lack of involvement in planning or decision-making about services (for review see [Citation17]). An investigation of supported decision-making was recommended as a priority in a review of the NDIS legislation [Citation18], and at the time of writing a public consultation had been promised.

Development of evidence-based support for decision-making practice framework

Achieving a substantive paradigm change in decision support for people with intellectual disabilities depends not only on the establishment of supported decision-making options but also on building the capacity of decision supporters. To fill the evidence gaps about practice and training, the La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework (the Framework) was developed [Citation19]. Intended as a guide to practice aligned with the intent of supported decision-making the Framework also provides the foundation for training supporters. The Framework was derived from a program of research about the components of effective support for decision-making for people with cognitive disabilities. Details of this program, the Framework, and steps in its development are published so not described in detail here [Citation19–21]. In summary, the Framework sets out that effective practice for decision support encompasses; three principles (commitment, orchestration, reflection & review), seven steps (knowing the person, identifying and describing the decision, understanding will and preferences, refining the decision to take into account of constraints, considering if a formal process is needed, reaching the decision and associated decisions, implementing the decision and seeking advocates if necessary), and an array of strategies tailored at each step to the decision, context and person. diagrammatically represents the Framework.

Study aims and research questions

This paper reports on a subset of data from a study that aimed to fill the gap in evidence about building the capacity of decision supporters. The study used mixed methods, qualitative interviews, and the completion of several quantitative measures, to explore the influence of an evidence-based training package, based on the Framework, on the quality of decision support provided to people with intellectual disabilities. Specifically, the training aimed to increase supporters’ capacity to enable participation of people with intellectual disabilities, respect their will and preferences, and use strategies reflecting evidence about effective practice. Drawing on a sub-set of qualitative data from the study, this paper reports findings of the following questions: (1) How do parents of adults with intellectual disabilities reflect on training about decision support practice and the relevance of the Framework? (2) How do parents perceive that training about decision support practice impacts their day-to-day provision of support?

Method

We used a social constructionist theoretical perspective, reflecting the focus on the subjective realities of decision supporters of people with intellectual disabilities [Citation22]. In line with a social constructionist perspective, an exploratory qualitative design was used to generate data using semi-structured interviews and mentoring sessions, focussing on participant reflections about their learning and behaviour, and other changes following the training. Approval was given by the University Human Research Ethics Committee and all participants gave informed consent to participate.

Sample and recruitment

Participants were recruited through information distributed about the study by industry organisations which were research partners and the researchers’ networks of advocacy, parent, and disability support organisations. Participants were 18 parents who regularly supported the decision-making of their adult son or daughter with intellectual disabilities, and who participated in a training intervention based on the Framework. Parents’ ages ranged from 47 to 74 years with a mean of 59 years, and thirteen were mothers. They lived in the three Australian states, Victoria, Queensland, and New South Wales. The adults they supported ranged in age from 19 to 39 years with a mean of 27 years. Most of the adults (15) lived at home with one or both of their parents. The severity of their intellectual disability was reported by parents and ranged from profound to mild. The age of each parent and the adult with an intellectual disability they supported, and the severity of each adult’s intellectual disability reported by their parent, are shown in .

Table 1. Age of parents and adults with intellectual disability, severity of disability, number of interviews and mentoring sessions conducted.

Training intervention

Parents participated in a one-day training session delivered to small groups by the first author or another experienced trainer. The session was based on the Framework and drew extensively on the video material available in the online training resources about supported decision-making [Citation23]. Following the training session, parents participated in up to six individual mentoring sessions that lasted up to an hour. Sessions provided an opportunity to explore the Framework further and discuss its application to their own context and specific decisions. Mentoring sessions were conducted by phone, with the first between 2 and 4 weeks post-training and the last before a final interview 11 months post-training.

Data collection

Data were generated through semi-structured interviews and mentoring discussions. Each parent was interviewed before the training and then following the training. The number of interviews and mentoring sessions each parent participated in are shown in . One parent was interviewed twice, 13 parents four times and 4 parents seven times. The period of time that elapsed between the training workshop and the first post-training interview, between subsequent interviews, and between mentoring sessions was dependant on the availability of parents and thus varied considerably between participants. On average however 3.4 weeks (SD = 2.1) elapsed between the training session and the first post-training interview. Twelve parents participated in six mentoring sessions and three participated in four sessions, two participated in two sessions and one participated in one session. The interviews asked parents to reflect on their support for decision-making and to describe a recent instance in detail. During the mentoring parents talked about specific instances of decision support. In the later interviews and the mentoring, without prompting, many parents reflected directly on what they had gained from the training and mentoring, and how it had informed their support.

The initial interview was conducted face to face and subsequent interviews by phone, in person, or using video conferencing. Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min and were conducted by the third author and an experienced research assistant between December 2016 and June 2020. Interviews and mentoring sessions were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

NVIVO v.12 was used to support the analysis and manage the data. A template approach was used [Citation24], which, similar to Charmaz’s [Citation25] sensitising concepts, meant some codes were defined prior to the analysis. Initial template codes were informed by the research questions and the various components of the La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework and aimed to capture parents’ reflections and learning; their thinking about the value of the training and its influence on their support, and their reflections about the influence of the training on their actions and the way they provided support. For example, initial codes included, identifying the decision and thoughts about the diagrammatic representation of the support process. Other codes were developed inductively as the analysis progressed. Line by line coding, using grounded theory techniques [Citation22] was followed by focussed coding to identify themes, which were then refined into broader thematic categories. The analysis was undertaken by the first author in regular discussion with the second author. The emergent themes were then discussed and refined further by the other authors.

Findings

Two core categories captured parents’ reflections about the Framework and their learning from the training in terms of changes to their thinking and actions: a catalyst for reflecting and rethinking perspectives and taking a more deliberative approach to supporting participation. A third category captured parents’ reflections on changes in the person they supported as a result of their own changed approach to supporting decision-making: perceived greater confidence in expressing preferences. . presents the core categories and sub-categories. These are illustrated in the sections below using data extracts. The source of quotes is indicated by the name of the parent and the letter M for mentoring, or I for interviews I, and a number signifying which instance they came from, that is, Jane, I, 3 indicates the quote is from the third interview with the parent Jane. All names have been changed to provide anonymity.

A catalyst for reflection and rethinking perspectives, “made me stop and think”

Most parents were already familiar with and supportive of ideas about disability rights, but for some, the training was the first time they had heard about the CRPD in detail. Many thought the training helped them, as Gabby said in a mentoring session, to “stop and think” about how they provided decision support and whether it aligned with a rights perspective. Raymond’s comment in an interview, that the training had been “very helpful to reflect on how you have worked in the past” was illustrative of many of the things they said. Parents found reflection helpful for various reasons.

Realising their influence

Reflecting on their support helped parents to realise the influence they exerted over the decision-making of the adult they supported. As Bernice and Misha explained, it helped them to be more aware of how many decisions they made without involving the adult and how much they influenced preferences in the way they provided support. They said,

I reflected on the fact that virtually everything that Sally does has been decided by me… The fact that she’s in work is because I have a goal for Sally that work should be part of her life. … I didn’t really engage Sally in the decision-making process other than to say… “Wouldn’t it be a good idea if you went and got a job?” (Bernice, I, 2).

I think that the mentoring has really helped with reflecting more about how you can impact someone or how you do it (Misha, I, 3).

Parents recognised the ease with which they exerted influence stemmed from their close relationships or the suggestibility or deference to others of their sons or daughters due to their intellectual disability and their limited experience with decision-making. Kate said,

…over these last few weeks, I’ve realised how many decisions I was constantly making …out of every person on the planet, he loves me the most. And therefore, he’s acutely vulnerable to suggestions that I make and my view of him, and my attitude towards everything that he might do or might be. Therefore, it’s very difficult to separate my intention from his (Kate, M, 2)

Committing to change

Reflection helped parents to recognise they might need to change their approach to decision support if they were to follow through on a commitment to rights-based support. Many were concerned when they realised their degree of influence. They reflected on how they might have done things in the past and resolved to try doing it differently to reduce their influence. They thought this would mean relinquishing some control over decisions and handing more to their son or daughter, irrespective of whether they reached what parents themselves might consider being the “right” decision. Parents also talked about giving more attention and respect to their son or daughter’s preferences, which would require continued self-reflection on their own values and influence. For example, Margot talked about how she might have exerted less influence about a decision about activity programs, and Gabby about relinquishing some of their control over decisions,

I probably spoke about the good things with [drama]. But I probably only spoke about the bad things with [service]…I could’ve changed that…The fact that I should’ve probably talked to him about – the good times he’s had at [service], … the times that he’s enjoyed the service, the beautiful environment it is, the way he’s been there now for three years and it has been good… I could’ve reinforced all those things. (Margot, I, 3)

I’ve got to be a bit more aware of my own opinions of things, so just stand back a step and say is this really what Caleb might want…I think it’s made me stop and give it a bit more thought. …it’s made me think. (Gabby, I, 2)

The training helped some parents rethink their perceptions about their son’s or daughter’s participation in decision-making, and be more alert that they often expressed their preferences in ways that were not clear or direct. For example, Gabby and Raymond, said,

…what this has really done though is it’s focused to me a little bit more…it has actually changed some of my language, the way I speak about it…I always used to call Caleb a non-decision-maker and I’ll never ever, ever in my life call him that again because very few people are non-decision-makers to be honest. (Gabby, I, 4)

I think for me it’s the reinforcement of the thing of listening and being alert to preferences as distinct from decisions… and I’m a bit more alert to listening for her preferences amongst all of her chatter as opposed to thinking how am I going to manage this situation. That’s a different outlook. (Raymond, M, 2)

One parent reflected on how she restricted full exploration of options around some decisions and her daughter’s preferences by focussing too much on possible constraints. She said, “I think of the constraints first rather than what she wants to do” (Misha, M, 2). Gabby also reflected how she would try to promote positive views about participation in decision-making more widely to change perceptions of other parents who were often dismissive of their son or daughter’s capability to express preferences. She said,

…I’ve actually got confidence now to correct them… I actually do that now. Even people who have these kids [and say], “My person’s non-verbal” and I go, “Do they make any noises?” They go, “Yeah.” “Well, why do you call them non-verbal? Those noises mean something.” (Gabby, M, 4)

Recognising the difficulties

Finally, reflection helped parents gain insights into some of the difficulties they experienced ensuring the adult they supported participated in decision-making. This helped them be more aware of what they needed to do. For example, both Brett and Raymond reflected on the discipline and energy needed to continually seek out and respect the preferences of their daughters to enable their participation in decisions. They said,

It can take a lot of energy, to try to make sure that Heather’s preferences are being taken into account as fully as possible. Very easy to be … lazy. Take the easy route and [about] some of the more day to day decisions, convince yourself, oh no, she doesn’t want to go outside right now, she can just stay inside. (Brett, I, 3)

Because it’s really hard to be disciplined, to continue asking open-ended questions and continue to pass over responsibility. But I feel confident to know I can do it if I turn my mind to it and keep disciplined… it is a discipline, it’s not a natural tendency. (Raymond, I, 3)

Similarly, Nara reflected that she didn’t always have the patience and time she needed to provide good support to her daughter,

…sometimes I’m impatient, so I just decide myself: “it’s okay; choose this one.” It shouldn’t be, but otherwise you have to sit down one hour, and then she might say, “I don’t know, I don’t know.” (Nara, I, 4)

Parents identified the lack of any external reinforcement as one of the difficulties of remaining focussed on good support. Several suggested that the NDIS discouraged rather than facilitated participation of people with intellectual disabilities in decision-making. For example, Kate said about the NDIS,

… they don’t really ask us whether the person that we’re making the decision for has been consulted. There isn’t any form that you get saying, “Did you speak to the participant about this? Do they agree?” It’s nowhere. So they’re perpetuating the old system, which is that parents act for children, and that doesn’t matter how old the children are…Sometimes planners don’t even talk to him. They just talk to me. (Kate, I. 7)

Taking a more deliberative approach to supporting participation, “having a structure”

The training influenced parents’ actions as well as their thinking. Their comments suggested parents were taking a more deliberative approach to support than previously. Bernice (I. 3) for example, explained that her confidence in providing support to her daughter had increased, saying, “[I am now] consciously doing it [providing support], and probably when we talked about it initially, I just wasn’t thinking as consciously as I perhaps am now.”

Using the framework as a point of reference

Parents found the structure of the Framework useful in guiding their practice and giving them language about decision support. Some referred to using the diagrammatic representation of the Framework as a prompt to remind them of the steps, or a checklist to reflect on their support. For example, Carol talked about the way she used the Framework, and Raymond about its value in giving him and his wife a shared language to talk about decision support,

…one of the things that [the trainer] gave us was a nice little wheel around the decision-making process. I love having a structure like that…so I kind of like that idea of checking in and have I covered all the different bases. And I am not just going on what I think as I have done in the past. (Carol, I, 2)

I think it’s been really fruitful because we’ve got two parents that think differently … and it’s been helpful to give us a structure to think along the same lines. (Raymond, I, 3)

Brett (I, 3) suggested the Framework provided something more concrete that helped him put the theory of supported decision-making into practice with his daughter. He said,

I feel like I’ve tried out some of the principles of practice of the support for decision-making and experienced them, felt like they’ve worked. Even just as an example, … realising that there’s a way to weigh up the options of what would it mean to keep Heather at the service on a Monday. What would it mean to change? And just going through some intentional stages or steps of thinking it through and realising that it can actually, and does actually, work (Brett, I, 3)

The next three sub-categories illustrate how parents described their support had changed since using the Framework by creating more decision-making opportunities, paying greater attention to preferences, and including others more.

Searching out new opportunities for participation

Prompted by the second step in the Framework, identifying and describing the decision, parents described ways they were trying to increase their son or daughter’s involvement in decision-making. They more consciously described the scope of decisions, identified decision-making opportunities, and were becoming more attuned to the way decisions were often embedded in each other or could be broken down into constituent parts. For example, Bernice talked about how she was approaching decisions differently:

… in the past, what I’ve done always is just get the list and you’ve got to select and rank order. And so, this time I thought “right I’m not going to just go to my diary and just write stuff in, I’ll print this out and show it to Sally, discuss it with Sally and give her an opportunity to actually select stuff” (Bernice, M, 4)

The mentoring prompted Brett to identify and revisit long-standing decisions about daily activities for his daughter to give her the opportunity to be involved in the decision about what time she went to the program and respect what he interpreted from her reluctance to get up as her preferences for a slow start to the morning. He said,

Then all of a sudden, it’s like what else – where else could we be offering her more choice…, you just prompted … our thinking about her daily timetable at … the Day Centre she’s at. She usually starts there at 9 o’clock each day. It’s often quite difficult to get her out of bed and get her moving in the morning so one of our decisions is actually is it possible that we start her day later…Maybe rather than having to struggle with having the morning to get out of bed we could just arrange her day so she gets the choice, she can get up later. (Brett, M, 1)

The sixth step in the Framework, reaching the decision and associated decisions had also prompted some parents to identify more decisions and opportunities for involvement. For example, Raymond said about his daughter,

…she’ll come up, show me a recipe that’s in a magazine and say, “I want to do that.” And rather than saying “Well, we’ll do it tomorrow.” Because we’ve got to buy the ingredients and it takes two hours to cook, like doing all the planning associated with implementing that decision. Now I’m more prone to say, “Well, who do you want to do it with or where do you want to do it?” Sort of bringing [her] into it and let her make choices. (Raymond, I, 3)

Greater attention to hearing preferences

Reflecting on step three, understanding the person’s will and preferences for the decision, parents talked about spending more time exploring options and the person’s preferences about these. For example, Joanne thought the quality of her support had improved and she had greater insight into her son’s preference from applying what she had learned about communication strategies in the training. She said,

… not that we didn’t really listen to what he was saying before, but really listening now. Like, taking on board what he’s saying and trying to go deeper and deeper, and peel off the layers, and trying to discover what he’s actually saying…. Trying to ask him more questions, and questions that he’ll understand better, in a different format, and really trying to get into the root of it basically…sort of coming at it in a different way, rather than just a direct hit, which doesn’t always sit well with him. So, I feel I’m in a better position to do that. I’m more patient, I’m able to listen more and hear what he’s actually saying, and not what I think he’s saying. (Joanne, I, 2)

Another parent described how she had encouraged her daughter to express her dreams through drawings in a series of short meetings, to ensure her will and preferences were better reflected in her NDIS plan goals than previously. She also contrasted her own attention to her daughter’s preferences now compared to before the training,

…and it’s different because Tamara’s very much involved…previously [pre-mentoring] it wouldn’t have unfolded like this and I can just see she’s really, really chuffed about being the centre of it. … I guess I’m just learning that when she says she wants something to happen she’s pretty correct…she doesn’t comprehend perhaps the implications of things. But intuitively she’s strong…I think I’m learning to go with her gut feel on things. (Misha, I, 3)

Brett described how he was giving opportunities for his daughter to express a preference about when she went to bed by taking more note of her response when offering assistance to get up from her chair. He said,

If she’s not ready to go up to her room, … if I just wait, give her a couple of minutes, go back and just offer her my hand and see if she chooses to stand up and come with me or not. If she doesn’t, give her another couple of minutes and try again. Eventually she’s ready to move and come with me. I think that’s an area that I kind of pay a bit more attention to her and I think it’s working better… She’s got her own timetable and it’s not – her timetable doesn’t match my timetable. (Brett, I, 3)

Similarly, Raymond (I, 3) talked about paying more attention to ascertaining his daughter’s preferences by looking for patterns when she vacillated over time, saying, “So you get this sort of divergence of views, but I guess, in a way, we’re looking at a pattern of what’s said more consistently or more frequently than other things.”

Drawing in others to broaden perspectives

Parents gave examples of applying the principle of orchestration by deliberately involving more people in decision support to bring alternative perspectives and more fully explore or understand the person’s preferences. Some did this by encouraging the decision-maker to seek the views of others, or themselves brought in other people to be involved in decision support. Mary, for example, said she had encouraged her daughter to seek advice from a family friend, and Kate noted that she had begun to draw in a circle of people with more diverse views to support her son. They said,

They’ve been able to raise things with Danielle that I would not be able to. So, I’ve become aware that that’s a very useful technique because she’s more likely to listen to other people than me on some matters. … And I’ve sometimes said “You might talk to Jenny about those things. She can help you as well as go through the options… .” (Mary, I, 3)

I’ve put in place this circle of support, which was an idea that came from one of the other participants around the table [at the training]. Of people that Jasper can talk to about his decisions for things he wants to do, apart from just me. (Kate, I, 5)

Brett gave another example of orchestration, saying that he had realised he should more fully understand his daughter’s preferences about what she did during the day. To do this he had begun to draw in the perspectives of those who saw her outside the home, such as a swim instructor and other participants in the program she attended. He said,

Alice and I aren’t the only ones who spend time with Heather and watch her closely and try to interpret what’s going on. There are others, and that intentionally drawing them into the conversation is important and has been beneficial …one thing I’ve noticed and probably paid more attention to than I would have… is whenever I get a chance, I ask one of Heather’s new friends what kind of day they think Heather had…Bree said “Heather loved the bus, she hated the beach.” It’s very clear, no filtering or particular way of framing it. She just said what she saw. It’s quite helpful in that sense. (Brett, M, 3)

Misha (M, 2) commented on the positive impact of having brought someone else into decision support who countered her often protective stance with her daughter, saying,

And that’s why it’s quite good to have maybe somebody else involved in there because they can alert you or remind you that it might be actually possible.

Joanne applied the idea of orchestration by prompting others involved in her son’s life to follow her lead in providing more opportunities for him to participate in decision-making. Talking about the way she orientated new support workers she said,

…we do tell them, “We expect you to have a conversation with Brendon, don’t make all his choices for him. Encourage him to speak to you, express himself, like speak in longer sentences, express ideas and things that he wouldn’t necessarily talk to us about perhaps.” (Joanne, I, 2)

Perceived increased confidence in expressing preferences

Reflecting on step 1 of the Framework, knowing the person, parents commented on how well they knew their adult son or daughter but also recognised the dynamic nature of knowing them and adjusting their knowledge as their child matured from adolescence to young adulthood or into middle age. Gavin said,

So, there’s been a lot of development with him and it all came about because I gave him an iPad… So, it was the first device he really took to. So now he’s got a smart phone and he uses it really well…So he uses it to find any information that’s valuable to him (Gavin, I, 4)

Parents also drew attention to recent changes in the confidence of their adult son or daughter which they thought were associated with greater participation in decision-making, as a result of their own changed support practice. Joanne said about her son,

He’s making more and more decisions himself. Like, smaller ones but he’s taking ownership of them a little bit more. So, in terms of what he wants to eat, where he wants to eat sometimes if we’re not eating at home, what he wants to wear … He just beams. He’s a different person. There’s a smile on his face. His shoulders are upright and it’s like, “I’m choosing this and I’m making it happen. I’m not waiting for someone else to lead me.” (Joanne, I, 4)

Parents observed that their sons and daughters’ greater confidence in expressing and standing by their preferences, had also been noticed by others involved in their life. As Gabby said,

I see a change in Caleb that he feels like he can now make those decisions because people are allowing him to make those decisions by encouraging him to make them and that is putting him in a really, really good place to be honest. …I actually do think that he can certainly get his message across when he really is adamant about something much more than he used to, and he doesn’t give up anymore. And, I’ve even had one of the services that he’s been going to … a few times they said to me, “Well, your son’s becoming a real little advocate for himself.” (Gabby, M, 1, 6)

Brett described how he thought his daughter was learning to better communicate her preferences and express them more often. He said,

There probably is a little bit of increase, the way that she communicates things like that, or the way that she responds to communication from us…she has become more stubborn if she doesn’t want to go somewhere. Like if it’s time to leave the house and she’s not ready or doesn’t want to go, she’s actually become more difficult to convince her to go to the front door. …. Yeah, so there probably is a little bit of development there now that I think about it. (Brett, M, 3)

Discussion

These findings demonstrate the feasibility of building the capacity of parental decision supporters through evidence-based training, and specifically the impact of training that utilises the La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework. The training and associated mentoring influenced the thinking and actions of parents, helped them to apply the Framework to their individual context, and gave them a reference point for their support practice. Acting as a catalyst for reflection, the training helped parents to realise how much they influenced their son or daughter’s decision-making and the difficulties of maintaining rights-based support. In turn, such realisations helped parents see the value of self-reflection and commit to changing aspects of their support. The findings suggest that parents followed through on their commitment to change with actions that increased decision-making opportunities, paid greater attention to the expression of preferences, and drew in a wider range of perspectives to help in considering options and preferences. These changes were in the right direction and aligned with the principles of supported decision-making. They were however incremental rather than wholesale changes. These data reflected the findings from other studies that each instance of support differs, and the practice of a supporter can range from controlling to enabling, depending on the context, decision, values of the supporter and person being supported and their relationship [Citation9,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13]. The findings also illustrate some of the challenges parents face in providing rights-based decision support, particularly in terms of the continued focus, energy, and patience required, which have been identified in other studies of decision support [Citation11–13,Citation26] and are explored in other papers published from the present study [Citation10,Citation21,Citation27,Citation28].

The variability of the practice of each supporter depending on the decision and context, together with the difficulties of maintaining a focus on rights-based support identified in the study suggest the need for ongoing strategies that will continue to build supporters’ capacity. These could take the form of regular individual mentoring or peer support through communities of practice that assist parental supporters to maintain a momentum of change, apply the Framework to their individual context and reinforce the value of good practice to the person they support.

The findings suggest a ripple effect of training, as it influenced the nature of support, which in turn influenced the confidence of the people being supported (at least as perceived by supporters). Demonstrated also was the value to the quality of life that participation in decision-making brings and the ongoing developmental potential of people with intellectual disabilities to participate in decision-making. This was also evident in the small group of people with more severe or profound disabilities who were supported by parents in this study, for whom participation in decision-making sometimes relied on parents attending to their non-verbal behaviours and interpreting their preferences. The value of self-advocacy groups in learning skills and enabling people with intellectual disabilities to speak out about their needs have been well documented [Citation29]. In Australia, there have also been various initiatives to improve the capability of people with intellectual disabilities to exercise choice and control [Citation30]. However, self-advocacy or other initiatives generally do not include people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities, whose potential for continued learning has tended to be neglected as the focus shifted from a developmental to a rights model of understanding disability and training supporters. This study demonstrated the influence of good support on the development of the adults involved, whose severity of intellectual disability ranged from mild to profound. This suggests that building the capacity of all adults with intellectual disability might be a parallel strategy in furthering the exercise of rights, and value of evidence-based individual training models in decision-making such as those developed by Shrogen and colleagues [Citation31].

The study highlighted the interchangeability of strategies used in person-centred planning and those for decision support, as well as the multiple decisions often embedded in goals and plans. It provides a timely reminder that many visual and exploratory strategies embedded in the practice and explanatory texts on person-centred planning may be of value to decision supporters outside the context of planning [Citation32].

These findings suggest the potential of the Framework as the basis for a supporters’ checklist for reflecting on their practice, and as a means for others to review and if necessary, challenge the nature of decision support. As the parents in this study suggested, this type of external monitoring that also serves to reinforce good support is largely missing from the Australian service systems. Checklists based on the Framework might provide the first line of accountability of supporters and safeguard people with intellectual disabilities from the undue influence of supporters in interactions they have with funding bodies, such as the NDIS or service providers.

Limitations

This was a qualitative study of a one-day training session, access to associated online resources and follow-up mentoring, which did not control for the volume or timing of these. While all parents participated in a one-day training session, due to their commitments and unanticipated events the number of mentoring sessions and time between them was not consistent among the sample; some parents dropped out after one or two sessions, which also meant the number of interviews varied between participants. A strength of the study however was its non-experimental nature and thus findings that reflect the application of the Framework and parental learning to their own context rather than an experimental one, or as is often the case with training evaluations in respect of case scenarios or vignettes. A further limitation was that the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities about change to decision support were not captured, although strength was the inclusion of parents of adults who had severe and profound intellectual disabilities, who are often left out of studies as their sons or daughters are unable to easily provide their own perspective through interviews. Another limitation is that the data captured the change in discourses of parents, which was indicative of the potential change in their practice rather than what they actually did, which could only be captured through observation.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to capture the reflections of parents of adults with intellectual disabilities on the value of the training and the application of their learning to support practices. The focus was on changes to practice that reflected the Framework and thus associated with providing more effective support rather than outcomes for the people supported in terms of concepts such as reduced paternalism or increased empowerment which as Carney et al. [Citation27] suggest are elusive-concepts to measure. The study has demonstrated the efficacy of the Framework, and evidence-based training in building the capacity of parental decision supporters to bring it closer to the type of support envisaged by the rights paradigm and supported decision-making schemes. It points however to the need for ongoing strategies to assist supporters to maintain momentum for change, retain their focus on good practice, extend their skills, and reinforce its value to the quality of life of participation in decision-making. The findings also suggest that in parallel to building the capacity of supporters, greater attention could be given to the potential for continued learning about expressing preferences and decision-making of people with intellectual disabilities, particularly those with more severe levels of impairment who often do not participate in self-advocacy groups which support learning and confidence about speaking out.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Article 12: Equal recognition before the law 2014 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): United Nations Human Rights. Committee on the rights of persons with disabilities; 2014 [cited 2021 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/crpd/pages/gc.aspx

- Arstein-Kerslake A. Restoring voice to people with cognitive disabilities: realizing the right to equal recognition before the law. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2017.

- Bach M, Kerzner LA. New paradigm for protecting autonomy and the right to legal capacity. Ontario (Canada): Law Commission of Ontario; 2010.

- Then S-N, Carney T, Bigby C, et al. Supporting decision-making of adults with cognitive disabilities: the role of law reform agencies - recommendations, rationales and influence. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018;64:64–75.

- Kohn NA, Blumenthal JA, Campbell AT. Supported decision-making: a viable alternative to guardianship? Penn State Law Rev. 2014;117(4):1111–1157.

- Browning MJ. Developing an understanding of supported decision-making practice in Canada: the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities and their supporters [dissertation]. Melbourne (Australia): La Trobe University; 2018.

- Arstein-Kerslake A, Watson J, Browning M, et al. Future directions in supported decision-making. Disabil Stud Q. 2017;37(1).

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Carney T, et al. Delivering decision-making support to people with cognitive disability — what has been learned from pilot programs in Australia from 2010 to 2015. Aust J Soc Issues. 2017;52(3):222–240.

- Browning M, Bigby C, Douglas J. A process of decision-making support: exploring supported decision-making practice in Canada. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;46(2):138–149.

- Bigby C, Douglas J, Smith E, et al. Parental strategies that support adults with intellectual disabilities to explore decision preferences, constraints and consequences. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2021. DOI:10.3109/13668250.2021.1954481.

- Curryer B, Stancliffe RJ, Dew A. Self-determination: adults with intellectual disability and their family. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;40(4):394–399.

- Curryer B, Stancliffe RJ, Wiese MY, et al. The experience of mothers supporting self-determination of adult sons and daughters with intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(3):373–385.

- Taylor WD, Cobigo V, Ouellette-Kuntz H. A family systems perspective on supporting self-determination in young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(5):1116–1128.

- Carney T. Supported decision-making in Australia: meeting the challenge of moving from capacity to capacity-building? Law Context. 2017;35(2):44–63.

- Commonwealth of Australia. National disability insurance scheme act 2013. Canberra (Australia): Commonwealth of Australia; 2013.

- Cukalevski E. Supporting choice and control—an analysis of the approach taken to legal capacity in australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Laws. 2019;8(2):8–19.

- Bigby C. Dedifferentiation and people with intellectual disabilities in the australian national disability insurance scheme: bringing research, politics and policy together. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;45(4):309–319.

- Tune D. Review of the national disability insurance scheme act 2013. Removing red tape and implementing the NDIS participant service guarantee. Canberra (Australia): Commonwealth of Australia; 2019.

- Douglas J, Bigby C. Development of an evidence-based practice framework to guide decision-making support for people with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury or intellectual disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):434–441.

- Bigby C, Douglas J. Supported decision-making. In: Stancliffe R, Wehmeyer P, Shrogran K, editors. Choice, preference, and disability: promoting self-determination across the lifespan. Amsterdam (The Netherlands): Springer; 2020. p. 45–66.

- Bigby C, Douglas J. Examining the complexities of support for decision-making practice. In: Khemka I, Hickson L, editors. Decision-making by individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: research and practice. Amsterdam (The Netherlands): Springer; 2021.

- Bryant A, Charmaz K. The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE; 2007.

- The La Trobe Support for Decision-making Practice Framework. An online learning resource [Internet]. Melbourne (Australia): La Trobe University; 2018 [cited 2021 Feb 17]. Available from: www.supportfordecisionmakingresource.com.au

- King N. Template analysis. In: Symon G, Cassel C, editors. Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research: a practical guide. London (UK): SAGE; 1998. p. 118–134.

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. 2nd ed. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE; 2003. p. 249–291.

- Bigby C, Whiteside M, Douglas J. Supporting decision-making of adults with intellectual disabilities: perspectives of family members and workers in disability support services. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2019;44(4):396–409.

- Carney T, Bigby C, Then S-N, et al. Paternalism to empowerment: all in the eye of the beholder? Disabil Soc. 2021. DOI:10.1080/09687599.2021.1941781.

- Wiesel I, Bigby C, Carney T, et al. The temporalities of supported decision-making by people with cognitive disability. Soc Cult Geogr. 2020. DOI:10.1080/14649365.2020.1829689.

- Mineur T, Tideman M, Mallander O. Self-advocacy in Sweden-an analysis of impact on daily life and identity of self-advocates with intellectual disability. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017;3(1)

- Anything is possible when your choice matters [Internet]. New South Wales (Australia): Council For Intellectual Disability; 2018. Available from: https://cid.org.au/our-stories/anything-is-possible-when-your-choice-matters/

- Burke KM, Shogren KA, Raley SK, et al. Implementing evidence-based practices to promote self-determination: lessons learned from a state-wide implementation of the self-determined learning model of instruction. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil. 2019;54(1):18–29.

- O’Brien CL, O’Brien J. The origins of person centred planning: a community of practice perspective. In: O’Brien J, O’Brien CL, editors. Implementing person-centered planning: voices of experience. Toronto (Canada): Inclusion Press; 2002.