Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the current review is to synthesize the evidence of patients’ perspectives of recovery after hip fracture across the care continuum.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted, focusing on qualitative data from hip fracture patients. Screening, quality appraisal, and a subset of articles for extraction were completed in duplicate. Themes were generated using a thematic synthesis of data from original studies.

Results

Fourteen high-quality qualitative studies were included. Four review themes were identified: recovery as participation, feelings of vulnerability, driving recovery, and reliance on support. Patients considered recovery as a return to pre-fracture activities or “normal” enabling independence. Feelings of vulnerability were observed irrespective of the time since hip fracture and only diminished when recovery of function and activities enabled participation in valued activities, e.g., outdoor mobility. Participants expressed a desire to engage in recovery with realistic expectations and the benefits of meaningful feedback reported. While reliance on healthcare professionals decreased towards a later stage of recovery, reliance on social support persisted until recovery was perceived to have been achieved.

Conclusion

Patient perspectives highlighted hip fracture as a major life event requiring health professional and social support to overcome feelings of vulnerability and enable active engagement in recovery.

Rehabilitation professionals should ensure expectations and goals are set early in the recovery process.

Rehabilitation professionals should ensure goals set with patients are tailored to the individual’s pre-fracture activities or “normal” promoting independence.

Rehabilitation professionals should monitor goals ensuring they are providing support, motivation, and managing expectations across the care continuum.

Rehabilitation professionals should address patients’ feelings of vulnerability, particularly in the absence of social support, and ensure appropriate ongoing input to maximize recovery.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

In the United Kingdom (UK), an estimated 70 000 older adults experience hip fractures each year [Citation1]. These fractures contribute to reduced mobility and independence affecting an individual’s health-related quality of life [Citation2]. Outcomes are often even worse for those with pre-existing conditions, such as dementia [Citation3]. In 98% of cases, older adults with hip fractures undergo surgery and subsequent rehabilitation in hospitals and the community [Citation4]. These interventions target a theoretical construct of “recovery” from hip fracture to determine the endpoint for care.

Recovery may be perceived differently depending on an individual’s role in the recovery process and more specifically, the point at which their role is completed. For example, a surgeon may consider recovery as “from fracture” achieved with fixation and bone healing or arthroplasty [Citation5] while physiotherapists may consider recovery as the attainment of pre-fracture function (e.g., mobility, activities of daily living) [Citation6]. These definitions of recovery highlight the time at which these professionals withdraw their care, rather than the time at which a patient and/or carer may consider themselves “recovered.”

More contemporary definitions of recovery were driven by the International Classification of Functioning with healthcare professionals, hospital administrators, and policymakers acknowledging the need to consider the role of body functions and structures as well as activities and participation in recovery [Citation7]. For hip fracture, previous quantitative research identified several domains of recovery including physical, instrumental, cognitive, affective, and social domains [Citation8]. Researchers highlighted variation in the time for recovery by domain informing a need for ongoing targeted healthcare professional support in the year post-fracture [Citation8]. This early research was based on quantitative evaluation using standardised outcome measures. While beneficial, in isolation it limits the potential for person-centred care as patients were not allowed to contribute by expressing their perspectives of recovery after hip fracture.

In 2011, a literature review of older adults’ recovery from hip fracture suggested patient recovery outcome is influenced by physical function and psychosocial factors [Citation9]. Since this time, there has been an influx of qualitative evidence exploring both patient and carer’s perspectives of recovery at different stages after hip fracture [Citation10–13]. This evidence adds depth to previous understanding of quantitative trajectories for recovery [Citation11,Citation12] as well as patient and carer’s perspectives of care received in support of recovery after hip fracture [Citation10,Citation13]. This evidence has been recognized through the publication of reviews synthesizing the evidence related to care about hip fracture from the informal carer’s perspective [Citation14] and the patient’s perspective of community-based rehabilitation [Citation15].

The purpose of the current review is to build upon previous work by considering patients’ perspectives of their recovery (encompassing but not restricted to rehabilitation) across the care continuum. More specifically, we will explore which patients are included in qualitative interview studies of recovery after hip fracture, when these interviews take place (about time since fracture), and which perspectives have been reported by patients about recovery after hip fracture.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies in adherence with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement [Citation16], and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [Citation17]. We registered the protocol for this review on the International Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO ID: CRD42020205858 [Citation18]. This review did not require ethical approval as all data is extracted from published literature available in the public domain.

Eligibility criteria

A summary of the eligibility criteria for studies included in this review is presented in .

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

We selected studies of “older adults” defined by the World Health Organization as those 60 years or older [Citation19] in receipt of rehabilitation after hip fracture surgery at any point along the care continuum [Citation12]. We included qualitative semi-structured interview studies as we sought to synthesize the evidence for patient perspectives after hip fracture which may not be captured by other qualitative designs, e.g., ethnography and/or quantitative design.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies of older adults who experienced multiple fractures [Citation20,Citation21], pathological hip fracture [Citation22], and those treated conservatively [Citation23], as their rehabilitation pathways and outcome vary from those with an isolated non-pathological hip fracture treated surgically. We excluded studies not published in English due to limited resources to cover translation costs.

Search strategy

We employed a pre-planned comprehensive search strategy to seek all available studies. We adopted previously published search terms for our strategies based on terms for “qualitative evidence” and “hip fracture” [Citation24–26], outlined in Supplementary File 1. The following databases were used to search for published literature: Medline, Embase, Psychinfo, and PEDro, Base, and OpenGrey were used to search for grey/unpublished literature. Searches were run from database inception to between 9 and 19 June 2020. We completed citation tracking of selected studies in Google Scholar on 10 July 2020 to identify any additional studies that may have been overlooked in our searches.

Screening

Two reviewers (NB and AR) independently screened the title and abstracts against eligibility criteria in Covidence software for managing systematic reviews. The same two reviewers independently screened the full text of potentially eligible articles against eligibility criteria. Reasons for exclusion were documented at full-text screening. Conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Quality appraisal

The conduct of the studies, their reporting, as well as the content and utility of their findings were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative research [Citation27]. This checklist includes the following domains: aims, methodology, research design, recruitment strategy, data collection, researcher relationship, ethical considerations, data analysis, findings, and research contributions. The appraisal was conducted independently by two researchers (NB and AR). Conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

We extracted study characteristics and results onto data extraction templates created a priori in Excel. Two reviewers (NB, AR) piloted the data extraction template on one study and refined the template before completing the extraction for the remaining studies. Two additional studies were extracted in duplicate. The remaining 11 studies were extracted once. The following study characteristics were extracted: the paper details (author, year published, country, and city of study), the methods and analytical approach (study design and data collection method), study details (where and when the study took place, length of interviews, interview details, topic guide, and type of analysis), participant details (sample number and participant characteristics) and key discussion points. Data on patients’ perspectives were extracted from the results sections of individual studies (themes identified and supporting quotes).

Data synthesis

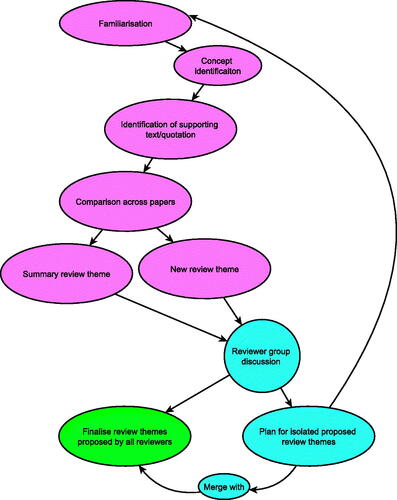

We adopted a thematic synthesis approach, outlined by Thomas and Harden which provides a clear link between conclusions and text of studies analysed () [Citation28]. This approach enables researchers to explore the perspectives of patients and highlight similarities and differences between their accounts. Three researchers (NB, AR, and KL) conducted thematic analysis independently. All authors individually read through all included papers first for familiarisation, and then generated concepts from the research data before coming together to discuss and finalise review themes. Themes in the current review were identified using data that included quotations from participants and text by the authors in the original papers. Data in each original paper were compared and organised into review themes and, where relevant, subthemes. The authors used an inductive approach to generate themes by observing patterns in the data within the original papers. Data in the original papers were collated and synthesised into variations of concepts defined by the original authors, and new concepts were created where deemed necessary. It was recognised that variations of the same concepts appeared in multiple studies, which informed the development of a new interpretation of the findings and the generation of novel and inclusive themes. Themes evolved further through discussion, re-reading of original papers, and re-evaluating content. Any conflicts were discussed until consensus occurred. Analysis was conducted using Excel and the NVivo qualitative data analysis computer software.

Results

Search results

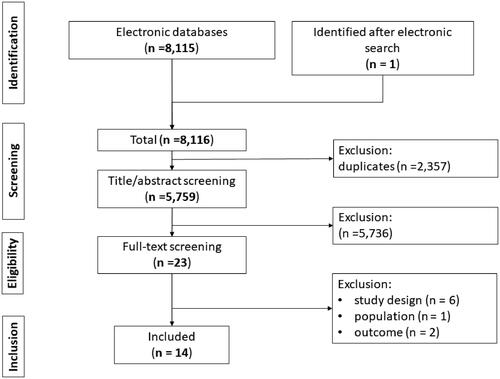

The results of the searches completed for this review are displayed in . We identified a total of 8115 potentially relevant studies. In total, 2357 were duplicates leaving 5759 studies to be screened. At this stage, 5736 title/abstracts were excluded, and 23 studies were brought forward to the full-text screening. Full-text copies of the 23 studies were acquired and evaluated against our predefined eligibility criteria. At this stage, nine studies were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria. One additional study published after the search date was identified through citation tracking of the remaining 13 studies. Therefore, 14 studies met the criteria for inclusion in this review.

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in . Four studies were conducted in the United Kingdom [Citation10,Citation12,Citation29,Citation30], three in Sweden [Citation13,Citation31,Citation32], four in Canada [Citation11,Citation33–35], one in Norway [Citation36], in New Zealand [Citation37], and one in the Netherlands [Citation38]. Two studies were carried out in the hospital setting [Citation10,Citation13], one a rural community setting [Citation31], and the remaining studies in urban community settings [Citation11,Citation12,Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–38]. Six studies selected their sample from participants of a randomized control trial [Citation11,Citation13,Citation32,Citation33,Citation36,Citation38]. Studies conducted included qualitative semi-structured interviews face to face [Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation36–38], via telephone [Citation11,Citation33,Citation35], or face-to-face and/or by telephone [Citation30,Citation34]. Where reported, the mean interview duration ranged from 5-min [Citation33] to 90-min [Citation34,Citation37]. Included studies made sense of their qualitative data by looking for patterns and coding using both inductive and deductive approaches. Five studies used thematic analysis [Citation10–12,Citation30,Citation33,Citation35], one used thematic and cross case analysis [Citation12], four used a phenomenological approach [Citation12,Citation13,Citation29,Citation36], two used qualitative content analysis [Citation13,Citation31], two used a constant comparison analysis (as part of grounded theory approach) [Citation37,Citation38], one used topic coding [Citation34], one used a phenomenographic method [Citation32], and one a systematic text condensation [Citation36].

Table 2. Study and participant characteristics.

Participant characteristics

14 studies included in this review reflect a total of 279 participants. Where reported, the mean age of participants ranged from 80 years [Citation32] to 81.5 years [Citation12]. One study included participants with cognitive impairment [Citation12]. Four studies did not mention cognitive status of participants [Citation11,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37]. The remaining studies excluded patients with cognitive impairment, scoring <15 [Citation36], or <21 [Citation38] on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), or <8 [Citation10] on the Abbreviated Mental Test Score. Other measures of cognitive impairment included ensuring that the patient was orientated cognitively to person, time, space, and situation [Citation31]. Three studies stated the exclusion of patients with cognitive impairments without a description of how this was determined [Citation13,Citation29,Citation32]. Two studies followed eligibility criteria from a parent study excluding potential participants who could not provide informed consent [Citation30] or with a prior diagnosis of dementia [Citation33]. Three studies included participants admitted from or discharged to residential care [Citation12,Citation34,Citation38]. The time since participants hip fracture varied from 8 days [Citation10,Citation13] to more than 1 year [Citation33–35,Citation37] across studies.

Quality assessment

Results of quality assessment using the CASP tool are presented in . There was 100% agreement (Cohen’s Kappa 1.0) between reviewers for all domains. All studies included in this review clearly outlined their aims and objectives. Studies clearly stated themes and subthemes and selected appropriate methodology to answer their research questions. Two studies successfully fulfilled all appraisal sections [Citation30,Citation36]. Reflexivity was considered in seven studies [Citation10–13,Citation30,Citation32,Citation36]; data saturation was discussed in six studies [Citation10,Citation12,Citation30,Citation34–36]. All studies had ethical approval. Eleven studies considered all ethical components of analysis, including a clear explanation of obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, and debriefing participants [Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation29–33,Citation36,Citation37]. Fourteen studies provided clear finding statements and discuss the clinical impact of findings [Citation10–13,Citation29–34,Citation36–38].

Table 3. Critical appraisal of study quality using the CASP qualitative appraisal tool.

Patient perspectives of recovery after hip fracture

Themes and subthemes

The themes and subthemes from the 14 studies included in this review are summarised in . From the data, we generated four review themes related to patient perspectives of recovery after hip fracture: recovery as participation, feelings of vulnerability, driving recovery, and reliance on support.

Table 4. Collating themes as described by original authors of qualitative interview into review themes: recovery as participation, feelings of vulnerability, driving recovery, and reliance on support.

Theme 1: recovery as participation

Across studies, participants considered recovery as a return to pre-fracture activities [Citation11,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation38] or “normal” [Citation13,Citation36,Citation37] enabling independence [Citation10,Citation29,Citation31,Citation34,Citation36].

“For me it is obviously, first and foremost, that I become independent in every way.” [66-year-old woman lived alone at home prefracture, interviewed 7 days postoperatively in hospital] [Citation13].

These activities were often described in terms of mobility [Citation12,Citation13,Citation37], such as walking outdoors [Citation13,Citation32]; activities of daily living [Citation29], such as going to the toilet [Citation13], gardening [Citation11,Citation12], cooking [Citation11] and housework [Citation32,Citation33]; as well as participation in social events [Citation37], such as meeting friends and family [Citation13,Citation32,Citation33], attending the theatre [Citation32], working as a volunteer [Citation32], shopping [Citation12,Citation32], and participation in sport [Citation11,Citation13].

“I just miss getting up and getting out. I never stayed in. I'd go out in the morning and come back and then I'd go out again, I just used to go out looking round the shops. I just get these crossword books and I do those” [92-year-old woman living alone at home, interviewed at home 5 weeks postoperatively] [Citation12].

The participants in some studies indicated they were willing to accept new normal if it enabled a sense of identity [Citation30] or preserved their ability to complete previous activities albeit in a different manner [Citation10,Citation38].

“Activities take up much more time; I did the gardening in a single day, and now I need three or four days because I get tired a lot sooner, and therefore, I divide up the activities” [78-year-old man living alone at home prefracture, interviewed at home 6–8 months post-fracture] [Citation38].

For two studies, several participants struggled to define recovery as the hip fracture was perceived as part of their decline with age with uncertainty over the future [Citation10,Citation12].

“They keep telling me that, the more I do, the better I’m going to be at it. But I think at the age I am it’s not going to be that easy you know? I’m hoping I’m wrong” [82-year-old woman living alone at home prefracture, interviewed in hospital] [Citation10].

Theme 2: feelings of vulnerability

Participants across studies reported new anxieties related to fear of falling, ability to cope at home, and feasibility of recovery enabling a return to valued activities, such as going out in the community and attending social events. These anxieties were particularly evident among older adults, those with poorer mobility, and with multiple long-term conditions. This often led to poor mental health which diminished only when valued activities resumed.

Participants in several studies highlighted a fear of falling as they felt they had a reduced capacity to overcome a subsequent injury in the future [Citation12,Citation30–32,Citation38]. Several participants reported adapting activities or avoiding them completely to minimize their risk of falls [Citation30,Citation31,Citation38]. Participants reported these fears at 1-year follow-up in one study [Citation30].

“You think, why didn’t I put the light on when I got up [at night]? … So, I’m very careful now, almost excessively so…. I’m careful when I’m out walking … Then I take it really easy! Look down at the ground … Now I’m afraid that it will happen again. And [that I will] break something else” [66-year-old woman, living with spouse at home, interviewed at home 1-year post-discharge] [Citation32].

Participants in two studies reported concerns around home life on discharge from hospital whether they would be able to cope [Citation10,Citation13]. In particular, participants highlighted anxieties related to becoming housebound and unable to engage in activities meaningful for their recovery.

“…I’m worried about how it will be when I come home, and I know that I won’t be able to go out…I haven’t said this to anyone before now, but that’s how I feel, I am, I’m worried about it” [89-year-old man living with wife at home, interviewed in hospital] [Citation13].

Concerns around coping and being able to return to previous activities often were often interwoven with fear of gradual and permanent decline in functioning following a hip fracture [Citation10,Citation30]. Anxieties related to declining were more apparent in older patients who often characterised their experience as a consequence of ageing [Citation10,Citation30], those with poorer mobility [Citation10], and those with multiple long-term conditions [Citation11,Citation30,Citation31]. Compounding these fears, participants felt if their hip fracture was treated in isolation (and not considered in the context of additional morbidities) their ability to recover would be impaired [Citation10,Citation11].

“I’m just not receiving the same kind of attention or treatment or even interest … I know that you’re focusing on the hip surgery recovery … the shoulder issue is much more annoying and upsetting to me than the hip. The hip recovery is basically straightforward … but [my shoulder is] not really being taken care of” [76-year old, interviewed at home 4 months post-fracture] [Citation11].

Participants described experiencing negative consequences, such as boredom, distress, loneliness, and depressive symptoms [Citation12,Citation30,Citation32,Citation36] up to 1-year after fracture [Citation30,Citation32]. Many attributed these feelings to reduced mobility and inability to attend activities outside of their home with friends and family [Citation12,Citation30,Citation36] which persisted in the longer term [Citation30].

“Makes me feel awful… I’m missing out on such a lot. I mean it was my granddaughter’s – well I said, her birthday today. And they’re gone out, you know. Lots of things… I didn’t want to get like this. I wanted to be, when I finished work, I wanted to carry on and do things” [80-89 year old woman living alone at home, interviewed at home 2.5 months post-operatively] [Citation30].

These negative consequences diminished overtime for some participants with increasing ability to return to valued activities [Citation30,Citation34].

“I’ve done it now, I’ve walked to the post box and I’ve walked to the shop and I’ve walked down to the library so I’ve – and back, so I – I’ve done that now… When you’ve done it, yeah, you – you – you feel, ‘Oh good, you know, that’s another mile gone, another milestone gone’” [80–89 year old woman living alone at home, interviewed at home 7 months post-operatively] [Citation30].

Theme 3: driving recovery

Participants across studies acknowledged a need for a positive outlook and active engagement in their recovery process. This engagement was reliant on a clear understanding of their recovery process with specific realistic expectations and goals tailored to their needs and activities. These expectations fueled motivation for engagement and coupled with positive feedback enabled transition to independent ownership of their recovery process. Unrealistic expectations or perceived generalized feedback were detrimental to recovery leading to feelings of frustration, disappointment, and reduced engagement.

Setting expectations for recovery trajectory

Participants discussed the importance of establishing realistic expectations and goals early with healthcare professionals as well as friends and family [Citation13,Citation33–35,Citation37]. Information received from staff, patients, and informal carers needed to be clear to facilitate confidence in expectations for their recovery [Citation10,Citation37] particularly at the point of discharge home [Citation31,Citation34].

“Staff should explain the other aspects of recovering from hip fracture such as time it will take; the adjustments one will need to make, the potential impact on a person, what to expect. Having these non-physical aspects would help increase confidence post discharge and assist recovery.” [interviewed at home] [Citation37].

Misalignment between expectations and reality of the recovery process led to frustration, disappointment, depressive symptoms, and reduced engagement with the recovery process [Citation32,Citation35,Citation36].

“My expectations for my own recovery were much higher than reality, and that have made me frustrated and impatient” [85–89 year-old woman, interviewed at home 3-4 months post-fracture] [Citation36].

“The doctor said in 3 weeks I’d be feeling fine and in 6 weeks I’d be back to everything, and I’m not. It’s a bit depressing. It’s been a long time” [80-year-old woman, interviewed at home 6-months post-operatively] [Citation35].

Motivation

Participants viewed the recovery process as a collaboration with health professionals [Citation10,Citation34,Citation38] but recognized the need for internal locus of control as self-efficacy was paramount to their recovery [Citation33–35].

“It’s the only way of getting through that barrier, is pushing. Physios can’t help you doing that, you’ve got to do that yourself” [84-year-old woman living at home alone prefracture, interviewed in hospital] [Citation10].

They reported the need for a positive outlook [Citation10,Citation11,Citation31,Citation33–35,Citation38] and self-reliance [Citation11,Citation30,Citation36–38] to maintain motivation and ensuring success in their recovery [Citation32,Citation37]. This motivation was positively reinforced through meaningful feedback on activity and participation goals from healthcare professionals [Citation10,Citation13,Citation33,Citation36,Citation38].

“It was nice to have someone rooting for me [and] gauging my level of activity” [66-year-old woman living at home with spouse, interviewed at home 6 and 12 months postfracture] [Citation33].

Participants sometimes reported needing to drive their own recovery independent of healthcare professionals when their care was not focused on their expectations and goals for recovery [Citation31]. This was particularly evident where participants described feeling passive towards recovery with decisions made for them rather than with them [Citation31,Citation36] failing to consider their individual priorities [Citation13]. To overcome this, participants reported completing activities independently they felt were in support of their recovery [Citation36].

“I went by myself to training and got out of the high walker entirely by myself, …….and I said to the nurse that now I have to start washing myself because I am going home. Yes, the nurse said, − without showing any interest” [85–89 year-old woman, interviewed at home 3–4 months post-fracture] [Citation36].

Theme 4: reliance on support

Participants reported reliance on both professional support and social support across studies included in the current review. The reliance on professional support was strongly observed for those in the early post-operative phase and decreased over time, which may reflect service withdrawal rather than a decrease in the need. Increased reliance on social support was observed for studies across the care continuum and was highlighted more for participants who were living alone.

Professional support

Participants reported a reliance on healthcare professional support for successful recovery in eleven studies [Citation10,Citation11,Citation13,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38].

Access to support from healthcare professionals (in particular physiotherapy) during the hospital stay was considered a facilitator of recovery [Citation36]. Participants reported a desire for “more” rehabilitation during this stage to support their recovery [Citation10,Citation31]. Participants reported frustrations when rehabilitation was not commenced early or regularly, feeling that this impeded their recovery, yet this decision was out of their control [Citation36,Citation37]. Participants in the study by Stott-Evenshen et al., indicated access to more regular rehabilitation was their rationale for enrolment in the rehabilitation research study [Citation33].

“I saw other people in the hospital recovering faster. I believe it was because they were getting more physiotherapy and more intense physiotherapy after the hospital … I would have liked to have had more physiotherapy but couldn’t afford it. I was eventually able to find something, but it would have been better to have had it sooner … I jumped at the study hoping for extra physiotherapy” [69-year-old man living alone, interviewed at home 6 and 12 months postoperatively] [Citation33].

Follow-up from healthcare professionals in the community was perceived to advance participants recovery [Citation33,Citation38]. Support from healthcare professionals was particularly important to those living alone [Citation10,Citation33,Citation35].

“I think the key for me was the physio people that I dealt with… [my PT] was great. I liked [their] approach to it and the reality that [they] brought to it – a bit of a Sergeant Major which was good – a delightful person who really gave me some clues as to how to handle it.” [71-year-old, interviewed at home 4 months postfracture] [Citation11].

Social support

Participants in several studies considered hip fracture as a disruption to their normal life leading to a new reliance on others to perform activities of daily living [Citation10,Citation11,Citation29–31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38]. Participants reported feeling grateful at being able to return home acknowledging this was often only possible with the support of family and carers [Citation29,Citation31,Citation33]. Many participants expressed frustrations and feelings of guilt related to these new levels of dependency and feeling of burdening their family and carers [Citation10,Citation11,Citation30,Citation32,Citation34]. For example, participants reported feelings of frustration due to reliance on family for support for activities they were previously able to complete independently [Citation10,Citation11,Citation30–32].

“If I went to the toilet I had to wake her up, break her sleep for her to get me back into bed you know, its things like that you know, it’s like being back in your second childhood again like you know” [<70-year-old man, living with wife and child with disability, interviewed at home 2.5 months post-fracture] [Citation30].

The perceived reliance on social support persisted for many individuals after hip fracture from the early post-operative phase to later stages of recovery. Participants often identified this reliance through a comparison of their current and pre-fracture activity levels [Citation35].

“[Before hip fracture] I could get to the shops; have a little three-quarters of an hour walk around the district. I always used to go down then I could finish going downhill home! [After fracture] I can get about the house, go up and down stairs but not go out, oh no. I couldn’t go out now” [interviewed at home in first 3 months post-fracture] [Citation29].

However, for many, a new normal evolved which led to perceived reductions in the degree of dependency on social support in later stages of recovery [Citation13,Citation29]. This new normal was often facilitated by the use of mobility aids, changes in the home, and adjusting activities [Citation12,Citation30,Citation31,Citation35,Citation37,Citation38].

“Ok, so I use a stick when I go out … I need secure hold … yes it's a symbolic thing, which means [it] just gives me space” [interviewed at home] [Citation37].

Discussion

Main findings

We identified 14 qualitative interview studies which explored patient perspectives of recovery after hip fracture. The overall quality of included studies was high. We identified four review themes from our synthesis of data from the 14 studies: recovery as participation, feelings of vulnerability, driving recovery, and reliance on support. Patients considered recovery as a return to pre-fracture activities or “normal” enabling independence. Feelings of vulnerability were observed for patients irrespective of the time since hip fracture and only diminished when recovery of function and activities enabled participation in valued activities. Participants expressed a desire to actively engage in recovery with realistic expectations and benefits of meaningful feedback reported. Reliance on healthcare support varied by time since fracture with patients highlighting a greater reliance on professional support in the early vs. late stages of recovery, particularly for those living alone. In contrast, reliance on social support persisted until recovery was perceived to have been achieved, irrespective of time since fracture.

Interpretation

For the current review, patients described activities/goals for recovery in terms of mobility, activities of daily living, and participation in social events. These descriptions align well with the International Classification of Functioning which outlines the role of body functions and structures as well as activities and participation in recovery [Citation7]. Of note, patients indicated the need for mobility to support activities of daily living and participation, e.g., outdoor mobility rather than as a goal in itself. These definitions were consistent across studies for those patients able to articulate what recovery means to them. However, a recent analysis of 24 492 patients indicated a weighted probability of up to 10% for recovery of mobility at 30-days among those able to walk outdoors pre-fracture [Citation39].

This poor early recovery may relate to contextual factors reported in the current review including multiple long-term conditions [Citation10,Citation12], and fear of falling [Citation8]. This fear of falling was often related to a perceived lack of reserve to overcome a subsequent injury. Indeed, up to 65% of older adults report low fall-related self-efficacy after hip fracture [Citation40]. Previous home-based rehabilitation intervention studies have demonstrated promise for improving falls-related self-efficacy after hip fracture [Citation41,Citation42]. Crotty and colleagues demonstrated patients enrolled for an average of 28 days on a target-orientated rehabilitation programme saw improvements in the Falls Efficacy Scale [Citation41]. Ziden et al. programme of balance confidence, physical function, and activities at daily living for 3 weeks following discharge also saw improvements in the Falls Efficacy Scale [Citation42]. The authors reported marked differences in the change in instrumental activities of daily living items of the Falls Efficacy Scale between groups (19.7 for intervention, 7.1 for control) which may signal a potential impact on the recovery of participation [Citation42]. Addressing poor self-efficacy for falls after hip fracture may better enable recovery through independence and participation in social events [Citation43].

Many considered their hip fracture as an event in a wider decline in their “normal” abilities. This “new normal” was acceptable to many if a sense of independence could be preserved. However, a definition for this “new normal” was not explored by any of the studies in the current review. Ensuing uncertainty may serve to reinforce feelings of vulnerability as, without a clear positive view of who they will become after their fracture, many patients consider the worst-case scenario – decline, loss of independence, transition to nursing care, and death [Citation44]. This perspective can lessen one’s self-image and increase feelings of alienation and social withdrawal [Citation45]. There is a need for rehabilitation professionals to set transparent realistic expectations, ensure they preserve patient choice in decision-making, and work towards patient specified valued activities. This will give hope and empower patients to define an evolving fresh narrative of self that preserves their desired self-image while reducing feelings of loss and restriction in everyday life [Citation46].

Value in healthcare relates to outcomes achieved, i.e., what matters to patients [Citation47]. In the current review, participants across studies acknowledged a desire for active engagement in their recovery across the care continuum. This finding is in keeping with previous reviews which identified a need for self-determination [Citation48] and a positive patient perspective in community rehabilitation as key drivers of recovery [Citation15]. For the current review, patients highlighted a desire for setting expectations and goals early, collaborative working with healthcare professionals to enable this active engagement to meet expectations, and a sustained positive outlook. However, this desire was not always met. This was particularly evident for the early post-operative period where patients reported feeling passive and lacked trust in decisions made “for them” and not “with them.” Moreover, patients reported anxieties related to preparedness for discharge home. The studies included in the current review did not identify reasons for the perceived absence of shared decision-making. As this was particularly evident in the early post-operative phase, it may reflect organisational pressures to reduce the length of stay transitioning patients to the community setting earlier [Citation49–51]. It is important that person-centered care is not compromised in efforts to meet these pressures [Citation52].

The current review supports a wealth of evidence indicating the patient-reported need for professional and social support after hip fracture [Citation15,Citation48]. The current review extends our understanding of support after hip fracture by highlighting patient-perceived needs vary by time since fracture for healthcare professional support. In contrast, patients' perceived need for social support varied by degree of recovery achieved irrespective of time since fracture. This discrepancy may be due to patient’s reflections on the withdrawal of healthcare services over time since their hip fracture, opposed to their perceived need for ongoing care. Indeed, several patients reported ongoing feelings of vulnerability, fear of falling, and fear-avoidance up to 1 year after their fracture – long after healthcare services ended. Of interest, a participant related their need for social support to both physical domains of health (e.g., going to the toilet, ability to walk outdoors to the shop), psychological domains (e.g., fear of falling), and social domains (e.g., attending a granddaughter’s birthday party). Many of these domains may be supported by health and social care services and align with previous quantitative research indicating a need for longer-term rehabilitation after hip fracture [Citation8,Citation53,Citation54].

The current review highlighted a lack of representation for patients with cognitive impairment and hip fracture in qualitative research. Up to 30% of hip fracture patients present with cognitive impairment [Citation55]. Physiotherapists recently reported a lack of confidence in using standardised care protocols with patients with cognitive impairment, expressing a desire for specialist training to enable a more patient-centered approach for these patients [Citation56]. An important step in developing more appropriate care for patients with cognitive impairment is gaining an understanding of what matters to them in their recovery after hip fracture. A previous systematic review of carers of patients with hip fracture identified 21 qualitative interview studies which reported extensive caregiver burden among those trying to support a person after hip fracture with cognitive impairment [Citation14]. Future research should consider the inclusion of patients with cognitive impairment and/or carers for those with severe cognitive impairment to better understand what is important in the recovery journey. This research may draw upon previous strategies to enable persons with dementia to take part in qualitative research, such as simplifying the structure of questions, allowing additional time for responses, and redirecting dialogue [Citation57].

Limitations

We updated our eligibility criteria from the protocol registration to include only adults surgically treated for hip fracture and irrespective of time since fracture (protocol indicated adults and carers in the first post-operative year). We did not include studies published in languages other than English nor did we search conference proceedings or for published dissertations which may have increased the risk of publication bias [Citation58]. We adopted a thematic synthesis approach. A limitation of this method is that data from the original studies are analysed out of context and concepts identified in one setting may not apply to another [Citation28]. We further acknowledge there is a level of uncertainty around our conclusions as we cannot be sure the data is completely representative of the older population recovering from a hip fracture. We did not have information regarding participants excluded from the study, for example, participants with cognitive impairments, or those too unwell to take part in interviews. Therefore, conclusions made from this review may not be representative of the underlying population with hip fractures. Finally, all studies included in the review were from countries with high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [Citation59], and are therefore not globally representative.

Conclusions

Patients considered recovery as a return to pre-fracture activities or “normal” enabling independence. Patient perspectives highlighted hip fracture as a major life event that requires health professional and social support to overcome feelings of vulnerability and enable active engagement in recovery. Future research should investigate the recovery perspective of patients with cognitive impairment, and further consider perspectives on recovery from carers.

Supplementary_files_Final.pdf

Download PDF (96.9 KB)Disclosure statement

KS received funding from the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit, the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Charitable Trust, and the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship for hip fracture health services research. KS is the current Lead of the International Fragility Fracture Network’s Hip Fracture Recovery Research Special Interest Group. NB, AR, BV, KL, and DW report no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Royal College of Physicians. National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) annual report 2019. London: Royal College of Physicians [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-hip-fracture-database-nhfd-annual-report-2019

- Castelli A, Daidone S, Jacobs R, et al. The determinants of costs and length of stay for hip fracture patients. PoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133545.

- Seitz DP, Gill SS, Austin PC, et al. Rehabilitation of older adults with dementia after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):47–54.

- Nahm ES, Resnick B, Orwig D, et al. Exploration of informal caregiving following hip fracture. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):254–262.

- Xu DF, Bi FG, Ma CY, et al. A systematic review of undisplaced femoral neck fracture treatments for patients over 65 years of age, with a focus on union rates and avascular necrosis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):28.

- Egol KA, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Functional recovery following hip fracture in the elderly. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(8):594–599.

- World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health; 2001 [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

- Magaziner J, Hawkes W, Hebel JR, et al. Recovery from hip fracture in eight areas of function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(9):M498–M507.

- Healee D, McCallin A, Jones M. Older adult’s recovery from hip fracture: a literature review. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2011;15(1):18–28.

- Southwell J, Potter C, Wyatt D, et al. Older adults’ perceptions of early rehabilitation and recovery after hip fracture surgery: a UK qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020. DOI:10.1080/09638288.2020.1783002.

- Langford D, Edwards N, Gray SM, et al. Life goes on.” everyday tasks, coping self-efficacy, and independence: exploring older adults’ recovery from hip fracture. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(8):1255–1266.

- Griffiths F, Mason V, Boardman F, et al. Evaluating recovery following hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of what is important to patients. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e005406.

- Asplin G, Carlsson G, Fagevik Olsén M, et al. See me, teach me, guide me, but it’s up to me! patients’ experiences of recovery during the acute phase after hip fracture. Eur J Physiother. 2021;23(3):135–139.

- Saletti-Cuesta L, Tutton E, Langstaff D, et al. Understanding informal carers’ experiences of caring for older people with a hip fracture: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(7):740–750.

- Blackburn J, Yeowell G. Patients’ perceptions of rehabilitation in the community following hip fracture surgery. A qualitative thematic synthesis. Physiotherapy. 2020;108:63–75.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA); 2020. [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: prisma-statement.org

- PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews; 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/

- World Health Organization (WHO). Aging and health; 2018 [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Penrod JD, Litke A, Hawkes WG, et al. The association of race, gender, and comorbidity with mortality and function after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(8):867–872.

- Di Monaco M, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, et al. Functional recovery after concomitant fractures of both hip and upper limb in elderly people. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(4):195–197.

- Willeumier JJ, van der Linden YM, van de Sande MA, et al. Treatment of pathological fractures of the long bones. EFORT Open Rev. 2016;1(5):136–145.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hip fracture: management; 2017 [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124

- Handoll HHG, Cameron ID, Mak JCS, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older people with hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007125. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007125.pub2.

- Parker MJ, Gurusamy KS, Azegami S. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD001706. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001706.pub4.

- Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S, et al. Clients' perceptions and experiences of targeted digital communication accessible via mobile devices for reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(10):CD013447.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Qualitative checklist; 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- Archibald G. Patients' experiences of hip fracture. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(4):385–392.

- Fox R, Gooberman-Hill R, Swinkels A, et al. Recovery from extra capsular hip fracture. A longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ experiences [dissertation]. Bristol: University of the West of England [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/883358/recovery-from-hip-fracture-a-longitudinal-qualitative-study-of-patients-experiences

- Segevall C, Söderberg S, Randström KB. The journey toward taking the day for granted again: the experiences of rural older people's recovery from hip fracture surgery. Orthop Nurs. 2019;38(6):359–366.

- Zidén L, Scherman MH, Wenestam C-G. The break remains – elderly people's experiences of a hip fracture 1 year after discharge. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(2):103–113.

- Stott-Eveneshen S, Sims-Gould J, McAllister MM, et al. Reflections on hip fracture recovery from older adults enrolled in a clinical trial. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2017;3:233372141769766.

- Schiller C, Franke T, Belle J, et al. Words of wisdom – patient perspectives to guide recovery for older adults after hip fracture: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:57–64.

- Sims-Gould J, Stott-Eveneshen S, Fleig L, et al. Patient perspectives on engagement in recovery after hip fracture: a qualitative study. J Aging Res. 2017;2017:2171865.

- Bruun-Olsen V, Bergland A, Heiberg KE. “I struggle to count my blessings”: recovery after hip fracture from the patients' perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):18–19.

- Healee DJ, McCallin A, Jones M. Restoring: how older adults manage their recovery from hip fracture. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2017;26:30–35.

- Pol M, Peek S, van Nes F, et al. Everyday life after a hip fracture: what community-living older adults perceive as most beneficial for their recovery. Age Ageing. 2019;48(3):440–447.

- Goubar A, Martin FC, Potter C, et al. The 30-day survival and recovery after hip fracture by timing of mobilization and dementia: a UK database study. Bone Joint J. 2021;103(7):1317–1324.

- Visschedijk J, Achterberg W, Van Balen R, et al. Fear of falling after hip fracture: a systematic review of measurement instruments, prevalence, interventions, and related factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1739–1748.

- Crotty M, Whitehead CH, Gray S, et al. Early discharge and home rehabilitation after hip fracture achieves functional improvements: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(4):406–413.

- Ziden L, Frandin K, Kreuter M. Home rehabilitation after hip fracture. A randomized controlled study on balance confidence, physical function and everyday activities. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(12):1019–1033.

- Taylor NF, Barelli C, Harding KE. Community ambulation before and after hip fracture: a qualitative analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(15):1281–1290.

- Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ. 2000;320(7231):341–346.

- Lloyd A, Kendall M, Starr JM, et al. Physical, social, psychological and existential trajectories of loss and adaptation towards the end of life for older people living with frailty: a serial interview study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):176.

- Soundy A, Smith B, Dawes H, et al. Patient's expression of hope and illness narratives in three neurological conditions: a meta-ethnography. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7(2):177–201.

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–2481.

- Rasmussen B, Uhrenfeldt L. Establishing well-being after hip fracture: a systematic review and Meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(26):2515–2529.

- Williams N, Hardy BM, Tarrant S, et al. Changes in hip fracture incidence, mortality and length of stay over the last decade in an Australian Major Trauma Centre. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8(1–2):150.

- Sobolev B, Guy P, Sheehan KJ, et al. Hospital mortality after hip fracture surgery in relation to length of stay by care delivery factors. Medicine. 2017;96(16):e6683.

- Nordstrom P, Gustafson Y, Michaelsson K, et al. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and short term risk of death after discharge: a total cohort study in Sweden. BMJ. 2015;350(1):h696.

- National Health Service England. What is personalised care? [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/what-is-personalised-care/

- Burns A, Banerjee S, Morris J, et al. Treatment and prevention of depression after surgery for hip fracture in older people: randomized, controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(1):75–80.

- Salpakoski A, Tormakangas T, Edgren J, et al. Effects of a multicomponent home-based physical rehabilitation program on mobility recovery after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(5):361–368.

- Mundi S, Chaudhry H, Bhandari M. Systematic review on the inclusion of patients with cognitive impairment in hip fracture trials: a missed opportunity? Can J Surg. 2014;57(4):E141–E145.

- Hall AJ, Watkins R, Lang IA, et al. The experiences of physiotherapists treating people with dementia who fracture their hip. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):91.

- Beuscher L, Grando VT. Challenges in conducting qualitative research with individuals with dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(1):6–11.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, et al., editors. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- The World Bank. GDP growth (annual %); 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG