Abstract

Purpose

To explore specialist amputee physiotherapists’ experiences and subsequent views about specialist inpatient rehabilitation (IPR) as a National Health Service (NHS) pathway option for adult primary amputees and their perceptions and beliefs about the effects of inpatient amputee rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

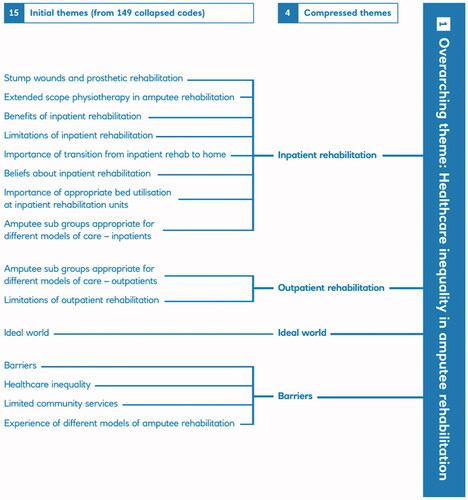

A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach. Semi-structured interviews were completed with seven physiotherapists experienced in working in both specialist amputee inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation settings. Interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed. Data were analysed using thematic analyses; inductive coding was completed; emerging themes are shown and a conceptual framework was developed. To promote rigour, this study was peer reviewed and coding was done by two people.

Results

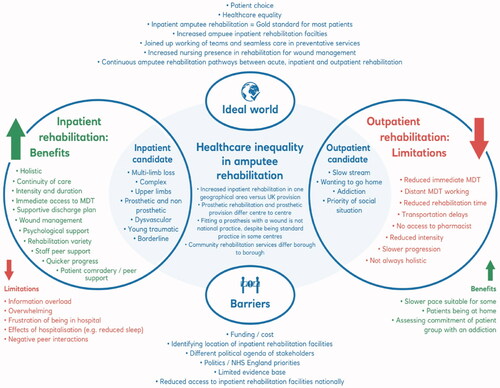

Clinicians believed inpatient amputee rehabilitation to be the preferred model of rehabilitation for the majority of adult primary amputees. A central theme of healthcare inequality within primary amputee rehabilitation provision emerged with four sub-themes: IPR, outpatient rehabilitation, barriers, the ideal world. Geographical variation was described in: type of rehabilitation provided, timescales of prosthetic rehabilitation provision, fitting a prosthesis with wounds, and the availability of community rehabilitation services.

Conclusions

Healthcare inequality is a central concern identified by clinicians who work within amputee rehabilitation in the UK. Clinicians interviewed believe NHS specialist amputee inpatient rehabilitation should be a more accessible pathway.

Clinicians believe healthcare inequality exists within primary amputee rehabilitation provision in the UK National Health Service (NHS).

Geographical variation in type of care provision, fitting a prosthesis with wounds, timescales in prosthetic rehabilitation provision and community rehabilitation services were described.

Clinicians believe inpatient amputee rehabilitation to be the preferred model of care for the majority of adult primary amputees and should be a more accessible pathway within the NHS.

Inpatient rehabilitation facilities may be a way of compensating for amputee rehabilitation inequalities.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease effects up to 20% of adults over the age of 70, with over 5000 major amputations undertaken in England annually [Citation1]. The five-year risk of amputation following revascularisation is high at 18% [Citation2] and the associated five-year mortality of those with a major amputation is as high as 52–80% [Citation3]. Major amputation causes both short- and long-term financial burdens for the National Health Service (NHS) and social care with NHS England spending an estimated £60 million per year on specialist rehabilitation for those with amputation or congenital limb deficiency [Citation4,Citation5]. Amputation is a life changing event effecting mortality, function, mobility, mental health, and a person’s overarching quality of life [Citation6]. Rehabilitation seeks to minimise the disabling effects of amputation for the individual [Citation7], and the economic consequence on health and social care [Citation8].

No randomised controlled trials or qualitative research investigating amputee inpatient rehabilitation (AIPR) or qualitative research were found from literature searches. The most recent systematic review of rehabilitation approaches to lower limb amputation does not discuss the role of inpatient rehabilitation (IPR) [Citation7]. However, prospective and retrospective cohort studies support AIPR as the most effective rehabilitation approach for amputees, with accelerated and improved patient outcomes. A prospective cohort study (n = 297) assessed prosthetic use and patient satisfaction following different models of rehabilitation of dysvascular amputees via telephone questionnaire six months after acute care discharge [Citation9]. Greater prosthetic use (17 h increase, p<.05) and prosthetic satisfaction were found for those who attended IPR versus a skilled nursing facility or home [Citation9]. A retrospective cohort study (n = 2673) identified those receiving IPR have an increased one-year survival (OR = 1.51, 95% CI of 1.26–1.80) than those with no evidence of IPR. This cohort were also more likely to be discharged home than those not attending an IPR (OR 2.58, 95% CI, 2.17–3.06) facility [Citation10]. Another retrospective cohort study found that patients discharged to IPR were significantly (p<.001) more likely to have survived 12 months post amputation (75%) than those at a skilled nursing facility (63%) or sent home (51%) [Citation11]. Patients discharged to a nursing facility were more likely to have a higher level of amputation (transfemoral) and be older (>75 years) compared to those discharged to IPR (p<.05), although there was no statistically significant difference found in comorbidities between groups. In addition, patients attending IPR have shown reduced depression and emotional suffering than patients discharged home or to a nursing facility [Citation12]. A UK retrospective analysis of patient functional and mental health outcomes following military IPR identified rapid physical and psychological improvement comparable with age-matched healthy individuals following an IPR program compared to normative data [Citation13]. The British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine draws on this evidence base to support AIPR as a pathway option in the UK [Citation14].

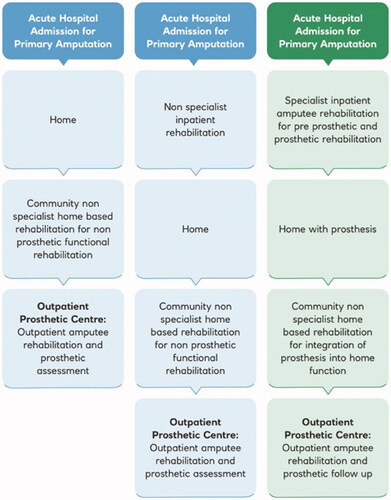

The UK, however, has minimal NHS specialist AIPR facilities, two of which are in the same geographical location within the Capital, London. Healthcare inequality in amputee and prosthetic services has been recognised by NHS England who have launched a review of prosthetic services following the results of their 2018 patient survey [Citation15]. The aim is to improve and ensure “equitable access to high quality care for amputees” and is supported by the vision shared in The NHS Long Term Plan [Citation16]. outlines the routine amputee rehabilitation pathway provided in the NHS versus an AIPR model available in some areas of the UK. It seems relevant and timely, in the context of an amputee rehabilitation and prosthetic service NHS England review, to investigate the role of specialist AIPR provision in the NHS.

Figure 1. Routine amputee rehabilitation pathway vs. specialist inpatient amputee rehabilitation pathway.

Gaining in-depth expert opinion in this area is an important starting point to further UK research into this topic [Citation17]. The purpose of this qualitative study is to identify and understand specialist clinicians’ experiences and subsequent beliefs about AIPR and to identify if the findings support the current evidence base.

Aims of study

To identify and explore specialist amputee physiotherapists’ experiences and views about specialist AIPR as a pathway option for adult primary amputees in the NHS.

To explore clinicians’ perceptions and beliefs about the effect of an AIPR approach for primary amputees in the UK and whether the type or subgroup of a primary amputee is an indicator for the rehabilitation pathway chosen.

Methods

Design

A qualitative phenomenological approach [Citation18], using individual semi-structured interviews as the data collection method [Citation19] to provide a depth and richness of participant beliefs and views from their experiences [Citation20]. Interpretation involved reflexively sorting data into progressively thematic groups with the aim of developing a meaningful interpretation. The study is reported according to SQOR guidelines [Citation21].

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted from the University of Hertfordshire; Health Science Engineering & Technology ECDA on 03/01/2019 as part of an MSc Research Investigation project. Protocol number HSK/PGT/UH/03623.

Reflexive statement

The lead researcher (JS) was a qualified physiotherapist with 11 years’ experience working within the field of amputee rehabilitation in the NHS who currently works as an advanced practitioner within an AIPR unit, with a special interest in the effectiveness of this approach. The researcher holds the belief that an inpatient approach to primary amputee rehabilitation is the optimum pathway for the majority of patients. The researcher believes this provides a rehabilitation program that is holistic and intense, expediting improvements in functional and psychological outcome and carried out this research as part of an MSc degree programme. Prior to starting the study, this researcher spent time reflecting upon her beliefs and assumptions and kept a reflective diary throughout the study. The second researcher (CML) has 24 years’ experience of carrying out qualitative research and supervised the study. Whilst the second researcher is also a physiotherapist by background, she works in predominantly academic and research settings and, to her knowledge, held no prior assumptions or beliefs about the effectiveness of different rehabilitation pathway options for amputees. The second researcher actively challenged the beliefs and views of the first researcher throughout, discussing them before the study, during data collection, and throughout data analyses. In this way, we sought to bring the insight and knowledge of the first researcher and the objective perspective of the second researcher together to benefit the research.

Participants

Purposeful sampling was adopted to ensure the selection of “information-rich” participants who had in-depth understanding of the phenomena to be investigated [Citation22]. Criterion sampling was specifically used, selecting participants with experience working in both a specialist AIPR and OPR (outpatient rehabilitation) setting [Citation23]. Physiotherapists were chosen for this study to represent a profession present at both models of rehabilitation with a holistic view of rehabilitation delivery [Citation6]. The role of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) in providing rehabilitation was considered and is acknowledged. However, it was beyond the resources for the current study to include, and achieve data saturation, for all professional groups and therefore the study participants were limited to physiotherapists [Citation24]. Participants were recruited from amputee rehabilitation specialist interest groups within the chosen geographical area of the study with physiotherapist members. Permissions were obtained from the specialist networks before sending the study recruitment flyer to the membership secretaries for distribution via email. The geographical location of the study was chosen to ensure participants would have exposure to both AIPR and OPR models, both present in the chosen location of the study ().

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Procedures

Participants were purposefully selected using the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Further sampling was not required. A participant information sheet and a consent form were sent to the selected participants for review via email, and an interview date and time was arranged. Interviews took place at either the participant’s place of work (n = 5) or the researcher’s place of work, an AIPR facility (n = 2). Signed consent forms were collected from participants before the interview commenced. The semi-structured interview guide was developed referring to qualitative research literature, using a mix of question types to capture demographic data, experience, opinion and feeling questions, tailored to meet the study aims [Citation20]. The semi-structured interview guide for the study was drafted by JS (), peer reviewed by CML and revised until the guide included non-leading questions to allow the aims of the study to be achieved [Citation18,Citation19]. The semi-structured interviews lasted up to 60 min (Median = 43 min). Interviews were completed between 17 January 2019–30 March 2019 [Citation24,Citation26]. Interviews were carried out by JS and recorded using a digital recorder (Olympus VN-540PC, Shinjuku City, Japan). Field notes were taken by JS [Citation27]. These included general feelings evoked during the interview, tone of voice, areas of the topic which sparked passion/enthusiasm/concern/sadness, any interruptions to the interview and the impact, body language, hesitancies to provide information, follow up questions and times when a participant needed guiding back to the topic. The first interview formed a pilot phase. This was fully transcribed and coded by JS. CML independently coded the interview and provided feedback regarding interviewer technique and initial coding.

Figure 2. Semi-structured interview guide [Citation25].

![Figure 2. Semi-structured interview guide [Citation25].](/cms/asset/147accd0-eb1f-44d9-a3e4-f2222d29542c/idre_a_1970830_f0002_b.jpg)

Data analyses

Audio recordings of the interviews were fully transcribed by the researcher and anonymised for any identifying characteristics of either participants or services [Citation28]. This included neutralising data due to the risk to anonymity within this small expert field, such as removing any colloquial language or identifying characteristics of participants. Initial coding (JS) was completed by re-reading the transcripts and identifying each spoken topic, line by line, and allocating an individual code. Thematic analysis was undertaken with inductive coding applied to develop a coding frame [Citation29]. The first interview transcription and coding was peer reviewed by CML and discussed [Citation30]. The next process was to group codes together which had the same meaning within each transcript and then across transcripts. Codes were then gathered together to show emerging themes demonstrated in [Citation29]. Renaming and the re-allocation of codes into themes became a fluid process [Citation31]. Using inductive thematic analysis the development of meaningful interpretation relevant to clinical practice emerged [Citation23,Citation32]. A reflexive diary was used throughout the research process, particularly in the analysis phase. Personal feelings and thoughts were included and reflected upon throughout the data analysis process, along with rationale for how codes were developed [Citation29]. This allowed for personal assumptions and beliefs to be transparent and challenged, whilst acknowledging the experience of the lead researcher. This reflexive approach helped to evidence trustworthiness within the study [Citation27]. The development of concepts in the context of the available evidence base of amputee rehabilitation is represented in : conceptual framework [Citation33,Citation34]. CML peer viewed and supervised all stages of the analyses and development of the conceptual framework. After completion of the MSc module CML coded all transcripts and cross referenced these against the initial codes, categories and emerging themes developed by JS to improve trustworthiness of data interpretation [Citation25,Citation28]. This measure, along-side the reflexive diary helped to capture if the lead researcher’s past experiences had influenced interpretation of the data and sought to identify this for discussion. Following the coding by CML, deviant cases and further details were added to the analyses and the conceptual framework slightly revised to improve clarity. Quotations which appropriately presented and represented the data were used to demonstrate the emergent themes. The quotations selected were sent to participants for member checking via email [Citation35]. Participants were given 10 days to reply. If there was no reply, as informed in the patient information leaflet, this was taken to mean that the participants were happy the quotations were a true representation of their views. This acted as a measure of conformability, ensuring the quotations were an accurate account of the data [Citation30].

Results

Of the 44 available staff, 15 responded to the invitation to participate in the study. Purposeful sampling was successfully used and seven participants were included who were information rich [Citation22], with the required experience to be able to answer the research question. Participants all worked within the NHS and had between 3 and 23 years of specialist amputee rehabilitation experience, all having experience of both AIPR and OPR. presents the number of years participants had worked within amputee rehabilitation. Two AIPR centres (50% of NHS AIPR centres) and two OPR centres were represented. Four participants had worked at more than one regional outpatient centre and drew on this wider experience. Additional demographic data such as age, ethnicity, and workplace have not been included within publication due to risk to anonymity. Further recruitment throughout the study was not required as data saturation appeared to be satisfactorily achieved by reviewing the codes and subsequent emerging themes through the data analysis process. No major differences between codes or themes were found between the two interviews completed at the AIPR facility and the five interviews completed off site.

Table 2. Participant demographic: experience in years.

One central theme emerged, with four related sub-themes (). These thematic concepts underpin the views and beliefs from the selected amputee specialist physiotherapists through their lived experiences of the phenomenon; AIPR, explained in .

The central theme which emerged was an overwhelming sense of “Healthcare inequality” in amputee rehabilitation, present throughout each sub-theme. Sub-themes included: the experiences and subsequent beliefs about amputee inpatient rehabilitation, outpatient rehabilitation, the ideal world scenario and barriers to the delivery of rehabilitation. presents quotations which illustrate these sub-themes.

Table 3. Supporting quotations to illustrate sub-themes for the study.

The semi-structured interview guide used did not ask about the benefits of IPR to avoid asking a leading question. During the analysis, it became clear that participants expressed their beliefs about AIPR effects in terms of benefits and limitations and although participants were not specifically asked about the outpatient pathway, analysis showed this was discussed as a comparison.

Inpatient rehabilitation

This sub-theme provided insight into the beliefs about the benefits of an AIPR approach including access to the MDT, the intensity and duration of rehabilitation provided and patient comradery. The approach promoted beneficial access to the MDT;

MDT working and collaborative working was a lot stronger and a lot more apparent [for AIPR]. (I/V 7)

they get really good continuity of care. (I/V 1)

Participants believed patients received increased intensity and variety of rehabilitation;

the intensity of the treatment you are receiving is greater. (I/V 2)

they get a lot of rehab in a short space of time… they progress… quicker. (I/V 1)

it’s a much more mixed bag [of treatment] …they attend an exercise group… they go to healthy living lectures…they do gardening… breakfast groups. (I/V 1)

Comradery and peer support were also considered beneficial. When reviewing the field notes alongside analysing the data this concept seemed of great importance to participants who spoke passionately about this.

a lot of comradery… the comradery is… a really good thing. It just allows patients to have time to talk to one another and share their experiences and realise they are not the only one who has lost a leg. They build up friendships that last quite a long time. (I/V 1)

Some limitations of an inpatient approach emerged too, these were important and relevant when considering which pathway to consider for individual patients. These were associated with general frustrations regarding hospitalisation as well as one negative view about the effects of peer support. The lead researcher’s (JS) interpretation from analysing the data and field notes was that the benefits of peer support outweighed the negative aspects. This was supported by the independent researcher’s analyses (CML), by the participants and fitted with the lead researcher’s own experience,

lack of sleep… one patient that’s just keeping the entire bay awake. (I/V 5)

you can get the odd bod in the group who can turn everything sour and then you get this kind of disruption that can be… negative at times. But I think 90% of it [peer support] works brilliantly. (I/V 4)

Due to limited AIPR resources, the need for appropriate bed utilisation was highlighted. By using a contextualist approach to data analysis, the lead researcher could empathise with this challenge, understanding that this could be seen as an example of health care inequality due to the unequal access to a resource;

if someone isn’t really that motivated… they’re probably not gunna [going to] use that time as effectively, and so might be stopping somebody else from being able to use that time. (I/V 6)

It was believed that the majority of amputees, no matter the reason or level of amputation, would benefit from an AIPR approach. This included upper limb amputees, experienced by the lead researcher as a patient group generally not considered for an IPR approach, primarily due to being independently mobile;

upper limb patients… really benefit from inpatient rehab… they felt more confident… they felt safer, they felt more independent. (I/V 3)

for borderline [prosthetic] patients… inpatient rehab gives you the best opportunity to see if somebody is suitable… you gather more information around cognition and problem solving, whereas if you’re seeing patient’s kind of once a week… those types of things are difficult to pick up. (I/V 7)

One participant described a different view: Their team were able to offer daily OPR in addition to AIPR so, bed pressures were described as an influencing factor on which pathway was offered. With bed pressures contributing to rehabilitation pathway chosen, healthcare inequality could arise. Furthermore, the provision of physiotherapy daily at one OPR was not offered at another, evidencing how rehabilitation provision varied dependent on which OPR centre a patient attended.

in terms of your simple patients… we try and push for them to be outpatients because… at our service we are able to offer daily rehab as an outpatient as well. (I/V 5)

we’re looking at the patient going ‘can you go home’ as we only have ten beds. (I/V 5)

Participants recognised an inpatient approach was the obvious choice for multi limb loss and complex amputees. This concept was discussed passionately by all participants, evidenced by powerful language, tone of voice, and participant body language;

Disastrous, I don’t see how you could send someone home as a quadrilateral amputee with the current ability of social services to provide input… let alone the psychological devastation of going though that. (I/V 1)

if they’ve… lost both legs and some upper limb loss… unhealed wounds, lots of scaring… they need intense therapy, nursing, doctor input, the whole MDT… it’s a no brainer that they need inpatient rehab. (I/V 4)

The importance of a seamless and supported transition home was considered paramount and AIPR allowed this to be carefully planned for, as opposed to acute hospital discharge planning “the discharge transition is a lot smoother and a lot more covered” (I/V 6).

AIPR emerged as the optimal model of primary amputee rehabilitation delivery for the majority of patients;

I think that an inpatient rehab unit is by far the best possible option’. (I/V 7)

I think it offers something unique and superior’. (I/V 2)

Outpatient rehabilitation

Participants described limitations of OPR for primary amputees including: transportation delays, reduced immediate access to the MDT, reduced rehabilitation sessions and intensity, and a longer route to reach patient goals. Outpatient rehabilitation intensity varied dependent on which centre patients attended. The examples shared by participants continued to evidence healthcare disparities within primary amputee rehabilitation, not only due to which pathway was followed (AIPR or OPR) but also between different OPR centres.

The reduction in OPR treatment time was understood by participants to adversely impact patient progression, identified as being a slower rehabilitation option lacking intensity;

For ‘quads… rehab would take forever’. (I/V 3);

it’s definitely a slower process… we tend to offer them once or twice a week. (I/V 1)

There was an overwhelming sense of a reduced immediate MDT, with less collaboration and reduced holistic focus demonstrating inequality between pathways with patient potentially missing expertise provided by different professions within the MDT;

outpatients will definitely have physio… most of them get OT [Occupational Therapy] but… not as much… We have got the availability of a clinical psychologist and a social worker but that’s not routine. (I/V 4)

they can still access a lot of that team but it’s a little bit more… disjointed. (I/V 6)

in an outpatient setting the appointments are very separate… sometimes you have no idea what’s going on in an OT session. (I/V 7)

OPR was considered more appropriate for patients who were “not engaging” (I/V 7) in rehabilitation or those preferring discharge home. This included those who were unable to tolerate the intensity of an AIPR program, those with other life priorities which impacted upon treatment and patients with supportive social networks to help them at home;

I think the social situation is a big determinant for which is the right service for an individual. (I/V 1)

Ideal world

Participants believed that “in an ideal world… AIPR is probably the best option for amputees” (I/V 1) for the majority of primary amputees, with a need for equitable access across the UK so that “a quick route to independent living” (I/V 7) can be promoted;

I would say 90% of amputees… would benefit from inpatient rehab. (I/V 4)

having that specialist knowledge and expertise all in one place [AIPR] is really beneficial. I think the majority of patients appreciate it and benefit from that. (I/V 7)

The lead researcher (JS) spent time reflecting on the below quotation, which brought feelings of sadness and disappointment about the reality of healthcare disparities within amputee rehabilitation in the NHS;

I like to think that… we can provide in the NHS… a good quality service, that’s standard around the country… that they don’t need to go private. (I/V 4)

These thoughts were captured within the reflexive diary to ensure transparency of these feelings, which could influence data analysis.

Providing patients with a choice about which rehabilitation pathway they followed was considered important for success;

if there were options of treatment that people could be provided, or offered the choice. (I/V 4)

because they have chosen to come… they are incredibly motivated to work hard. (I/V 1)

Ideal geographical locations of AIPR units were discussed. One participant advocated rehabilitation beds “being off site from the acute hospital” to ensure rehabilitation beds are not reallocated when there are acute bed shortages (I/V 3). Another option discussed was having all rehabilitation services on one site [AIPR and OPR] to enable smooth transition of care along the rehabilitation journey;

the ideal… is that you would have a… large site that would have your regional prosthetic centre… alongside your amputee inpatient rehab unit… the pathway would be even more seamless. (I/V 3)

Another benefit for rehabilitation beds outside of acute hospitals was to host environmental benefits such as rehabilitation gardens for occupational rehabilitation such as providing gardening groups (I/V 1).

Barriers

Participants identified the central barrier to patients accessing AIPR as being the disparity between provision across the country, this sub-theme highlighted more than any other the healthcare inequality present within amputee rehabilitation provision;

in xxx [hospital] we’re very lucky we’ve got inpatient beds… nationally, we know that’s not the case. (I/V 5)

we get a lot of patients from other areas… because there’s such a lack of AIPR units… patients… are often sitting on orthopaedic wards, vascular wards, … medical wards, so they’re not… getting the input they need. I think… these patients miss out on specialist care. (I/V 4)

There were concerns about inconsistencies between community rehabilitation services which differ borough to borough. This impacted on the success of a patient’s reintegration into home life as an amputee;

The main issue to think about is the transition from inpatient to outpatient…It depends on their area and what community services are available…you do see a bit of a drop off with patients after the inpatient stay. (I/V 1)

The challenge of identifying appropriate geographical locations of AIPR units was recognised;

I guess the only other barrier is where they are distributed. (I/V 6)

The lack of AIPR units was considered to be due to the initial increased cost of providing an AIPR service and lack of funding;

it’s expensive, but if you look at patient outcomes and their quality of life then I believe it outweighs the initial expense. (I/V 3)

I…hope that the NHS will realise the benefits of inpatient rehab. Even though… the financial costs are greater, it would be a false sense of economy to get rid of them…You may save initially, but it is such a complex patient group that if you set them up well from the very beginning you will save in the long term. (I/V 2)

The differing funding streams to support amputee and prosthetic services was highlighted as a challenge to overcome to improve care.

prosthetics and amputee services are funded in the main by NHS England on a specialist tariff… separate to vascular and diabetes pathways… they’re not merged from a financial modelling point of view. (I/V 3)

But the lack of resources and political pressures made future care uncertain;

I don’t know where the NHS is heading. (I/V 4)

This was a powerful statement, emotionally fuelled from genuine concern, field notes captured the emotion from body language and tone of voice.

Within the theme “barriers”, the overwhelming sense of healthcare inequality was strongly represented. Models of amputee rehabilitation experienced by participants was significantly different from service to service they had worked in;

Some of the prosthetic prescription they were using was… a bit more conservative to other prosthetic centres. (I/V 6)

it was three months [before limb fitting] and that was for like a…straight forward…case…Our…ethos here is…get them going as quickly as we can…to prevent any de-conditioning. (I/V 6)

Clinical treatment also varied, such as making a prosthesis with an open wound. Despite supporting evidence for this treatment and being standard practice in some services, it was not offered at other sites [Citation36];

the two main places I’ve worked in outpatients are quite different… so for example xxx, they don’t run things like the open wound policy. (I/V 6)

The semi-structured interview guide did not include questions relating to health care inequality. When analysing the data, it became apparent that the overall study aim which was to understand participants beliefs about AIPR was surpassed by the latent content running through all of the transcripts; healthcare inequality. This concept seemed powerful and was relatable to literature around this topic. The power of this theme was evident through language used by participants, body language and tone of voice. The lead researcher JS and second researcher CML reflected and discussed this theme at length, to fully understand the impact of healthcare inequality within primary amputee rehabilitation provision.

Discussion

This study has achieved its aim of exploring specialist physiotherapists’ experiences of AIPR and understanding their subsequent views and beliefs about this treatment option and its effects on primary amputees within the NHS for the first time.

Participants identified AIPR as the preferred model of care for the majority of primary patients. Furthermore, the results identified an overwhelming sense of healthcare inequality within primary amputee rehabilitation shown as the overarching theme. This study has recognised the necessity to standardise care provision, the need to break down barriers to achieving this and to improve access to AIPR nationally.

The findings presented in the theme “inpatient rehabilitation” are consistent with the evidence base, discussing the benefits of an IPR pathway for primary amputees and explores in greater detail the reasons associated with these improvements [Citation9,Citation12,Citation37]. The ability for peer support and immediate access to psychological/counselling professionals, immediate access to a comprehensive MDT including pharmacy and nursing professionals, with closer team working, and providing a rehabilitation program with greater duration, pace, and intensity, are identified by participants as contributing factors to why AIPR is believed to be the preferred pathway. These factors are supported in the literature. Pezzin et al. associate greater and lasting longer-term outcomes with IPR due to more “coordinated” interdisciplinary care, greater rehabilitation intensity (3 h per day) and extensive access to education from psychological professionals [Citation12]. Furthermore, immediate and intensive access to physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and the prosthetic service has been associated to greater prosthetic use. IPR is able to provide increased responsiveness to limb care and prosthetic fitting, linked to positive experiences with the device [Citation9]. A reduction in mortality and further amputation for those attending IPR is also represented in the literature, allowing chronic conditions to be further stabilised before discharge home, the ability to consult specialists easily, greater immediate wound management, and the capability to provide intensive holistic health education to both patients and carers [Citation11]. This detail may be useful for local services when reviewing their own service quality.

There is a known social gradient across many social and economic determinants that contribute to health, with poorer individuals experiencing worse health outcomes than people who are better off [Citation38]. There is a need to address inequalities in healthcare to address this gradient and improve outcomes for people in disadvantaged groups both in the NHS and globally [Citation39]. Healthcare inequality in relation to the accessibility of AIPR is reported in the literature. Dillingham and Pezzin recognise the variety in discharge destinations from acute hospitals for dysvascular amputees [Citation11]. This was dependent on the geographic region; some regions had increased access to IPR facilities than others. The findings of our study support this and have identified the reduced availability and access to AIPR facilities across the NHS. Whilst AIPR has been routine for the military population in the UK, this is not so for NHS patients [Citation14]. This healthcare inequality has been recognised by Murrison who stated The Defence Medical Rehabilitation Programme (DMRP), with its Consultant led multiple-disciplinary Complex Trauma Teams (CTTs) and IPR pathway “has no equivalent in the NHS” [Citation36].

This study identified further examples of healthcare inequality including variation of rehabilitation treatment between centres, both at AIPR and OPR facilities. Our study results support the NHS England’s Prosthetics Patient Survey (2018) which presented patient views about care received from Regional Prosthetic Centres [Citation15]. This survey clearly demonstrated healthcare inequalities, with a key theme being the “lack of clarity or consistency” in which resources and products are available in the NHS. Patients understandably wanted equitable access to resources. This was found not to be the case in the patient survey or in our study with prosthetic prescription and rehabilitation delivery varying between centres [Citation15]. The Prosthetics Patient Survey highlights that some of these inconsistencies may be attributed to local level service provision and policy [Citation15]. Our study findings identify clinicians express similar concerns about varieties in care with their “ideal world” allowing AIPR to be provided for all patients for whom it is indicated and where this approach is supported and agreed by the individual patient. This study highlights long waiting times for primary prosthetic provision at one OPR centre, versus rapid access at another and further research is required to explore and understand the reasons for this situation. A further variation in care was that at some centres fitting a transtibial prosthesis with a wound was standard practice whereas, despite evidence supporting this approach, this was not offered at other centres [Citation40]. This was believed to delay patient progression to prosthetic rehabilitation. Finally, one OPR centre was able to provide daily physiotherapy sessions for primary amputee rehabilitation, whilst another provided twice weekly physiotherapy for the majority of patients. Consideration is needed as to whether daily rehabilitation as an OP could be as beneficial as IPR. When reviewing the literature base, IPR does not only provide increased rehabilitation sessions and intensity, but a more holistic pathway, with varied rehabilitation options and greater access to an immediate MDT [Citation9,Citation12]. The benefits of incorporating these factors into a daily OPR service would need to be explored.

Wide variation in community rehabilitation services within the same geographical area has been previously identified and our findings are consistent with this variation in practice [Citation41]. This variance was believed by participants to be a contributing factor associated with differences in the success of patients reintegrating into home life following AIPR. Some boroughs were unable to support the transition from hospital to home and this was believed to adversely impact upon patient outcome following amputation. Our study also highlighted the importance of clear and appropriate amputee pathways between acute services, AIPR and OPR centres to ensure joined up and seamless transitions of care [Citation42].

Study strengths and limitations

This study adds to the very limited existing evidence exploring and evaluating AIPR. The study identifies and explores views not previously reported in the literature. It is recognised that this study included a small sample of physiotherapists with experience working at both AIPR and OPR facilities within a specific region and is not intended to produce findings generalisable across the NHS setting [Citation43]. Instead our research seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon, often missed in alternative quantitative survey designs [Citation44]. There was a wide age range of participants in the study but limited representation for gender and ethnicity. To expand on this work, future studies could consider sampling from the wider and larger MDTs, include participants from all four AIPR centres nationally and purposively sample for male physiotherapists and physiotherapists from varied ethnic backgrounds. Although not generalisable, the study findings are supported by literature within this field, and the study has identified barriers and inequalities which have raised questions for further research to investigate.

Second, this research was undertaken as part of an MSc project by an inexperienced researcher (JS). To promote rigour, an experienced researcher (CML) provided oversight for the study. She independently coded all transcripts in full, peer reviewed data analyses and revised the conceptual framework. It is considered a strength that the researchers provide different perspectives about the topic, JS works within an AIPR unit whilst CML is an academic researcher. JS was able to engage with participants, and understand the data fully within the context of both the literature and the challenges of delivering health care in the NHS [Citation45], whilst CML was able to question assumptions during analyses and provide a more independent viewpoint. A reflexive diary was used by the lead researcher (JS) throughout the research project and especially during data analysis. Member checking was also carried out to promote trustworthiness [Citation30,Citation45].

Finally, guidance on how to complete data saturation in the literature is limited, it is understood that achieving data saturation may not have been fully achieved due to time constraints when completing an MSc research project, however by the final interview, coding and subsequent thematic analysis indicated that no new topics were being identified [Citation24].

Conclusions

This is the first qualitative study design exploring different models of amputee rehabilitation provision within the UK. Further UK-based research into this area is required to develop the evidence base about amputee rehabilitation delivery within the NHS, to ensure patients receive high quality evidence-based care which is standardised across the UK. A larger, more generalisable national survey including multi-professionals is the logical next step to investigate this topic further. The NHS Prosthetic Evaluation Questionnaire sought to gain patient perspectives of prosthetic services [Citation15]. Building upon this, a qualitative approach may provide greater understanding of the patient’s perspective and experience of amputee rehabilitation provision in the UK.

The study findings raise concern about the healthcare inequalities which exist within amputee rehabilitation provision within the NHS, specifically access to AIPR. It is hoped that the study findings will be considered during the current national review of prosthetic and amputee services by NHS England to help to improve and standardise amputee rehabilitation for NHS patients.

Acknowledgements

This study has been completed in partial fulfilment for the award of an Advanced Physiotherapy MSc at the School of Health and Social Work, University of Hertfordshire, UK.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad N, Thomas GN, Gill P, et al. Lower limb amputation in England: prevalence, regional variation and relationship with revascularisation, deprivation and risk factors. A retrospective review of hospital data. J R Soc Med. 2014;107(12):483–489.

- Heikkila K, Loftus IM, Mitchell DC, et al. Population-based study of mortality and major amputation following lower limb revascularization. Br J Surg. 2018;105(9):1145–1154.

- Thorud JC, Plemmons B, Buckley CJ, et al. Mortality after nontraumatic major amputation among patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(3):591–599.

- Houghton JS, Urriza Rodriguez D, Weale AR, et al. Delayed discharges at a major arterial centre: a 4-month cross-sectional study at a single specialist vascular surgery ward. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011193.

- NHS_England. Prosthetics Service Review; 2018. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/group-d/d01/prosthetics-review/

- NCEPOD. Lower limb amputation: working together. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death; 2014. Available from: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2014report2/downloads/WorkingTogetherFullReport.pdf

- Ulger O, Yildirim Sahan T, Celik SE. A systematic literature review of physiotherapy and rehabilitation approaches to lower-limb amputation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34(11):821–834.

- Jordan RW, Marks A, Higman D. The cost of major lower limb amputation: a 12-year experience. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(4):430–434.

- Roth EV, Pezzin LE, McGinley EL, et al. Prosthesis use and satisfaction among persons with dysvascular lower limb amputations across postacute care discharge settings. PM R. 2014;6(12):1128–1136.

- Stineman MG, Kwong PL, Kurichi JE, et al. The effectiveness of inpatient rehabilitation in the acute postoperative phase of care after transtibial or transfemoral amputation: study of an integrated health care delivery system. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(10):1863–1872.

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE. Rehabilitation setting and associated mortality and medical stability among persons with amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(6):1038–1045.

- Pezzin LE, Padalik SE, Dillingham TR. Effect of postacute rehabilitation setting on mental and emotional health among persons with dysvascular amputations. PM R. 2013;5(7):583–590.

- Ladlow P, Phillip R, Etherington J, et al. Functional and mental health status of United Kingdom military amputees postrehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(11):2048–2054.

- BSRM. Amputee and prosthetic rehabilitation – standards and guidelines. 3rd ed. British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine; 2018. Available from: https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/prosthetic-amputeerehabilitation-standards-guidelines-3rdedition-webversion.pdf

- NHS England. Specialised commissioning: prosthetics patient survey report 2018. NHS England; 2018. Available from: https://www.engage.england.nhs.uk/survey/specialised-prosthetics-services/user_uploads/prosthetics-patient-survey-report-december-2018.pdf

- NHS_England. The NHS long term plan. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf

- Eibling D, Fried M, Blitzer A, et al. Commentary on the role of expert opinion in developing evidence-based guidelines. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(2):355–357.

- Dowling M. From Husserl to van Manen. A review of different phenomenological approaches. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(1):131–142.

- Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):314–321.

- Rosenthal M. Qualitative research methods: why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8(4):509–516.

- O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544.

- Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18.

- Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2009.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

- Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212–1222.

- Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2013.

- Braun V, Clarke V. What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. 2014;9(1):1–2.

- Hadi MA, Jose Closs S. Ensuring rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative research in clinical pharmacy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):641–646.

- Barker KL, Minns Lowe CJ, Toye F. 'It is a Big Thing': exploring the impact of osteoarthritis from the perspective of adults caring for parents – the sandwich generation. Musculoskelet Care. 2017;15(1):49–58.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Tuohy D, Cooney A, Dowling M, et al. An overview of interpretive phenomenology as a research methodology. Nurse Res. 2013;20(6):17–20.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(8):45.

- Torrance H. Triangulation, respondent validation, and democratic participation in mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6(2):111–123.

- Murrison A. A better deal for military amputees. Department of Health & Social Care; 2011. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215338/dh_130827.pdf

- Czerniecki JM, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al. The effect of rehabilitation in a comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation unit on mobility outcome after dysvascular lower extremity amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(8):1384–1391.

- Health profile for England; 2017. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-profile-for-england/chapter-6-social-determinants-of-health

- Donkin A, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Global action on the social determinants of health. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(Suppl. 1):e000603.

- VanRoss E, Johnson S, Abbott C. Effects of early mobilization on unhealed dysvascular transtibial amputation stumps: a clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):610–617.

- Neuburger J, Harding KA, Bradley RJ, et al. Variation in access to community rehabilitation services and length of stay in hospital following a hip fracture: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e005469.

- Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. The effectiveness of integrated care pathways for adults and children in health care settings: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2009;7(3):80–129.

- Constantinou CS, Georgiou M, Perdikogianni M. A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):571–588.

- Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, et al. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1272–1277.

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1985.