Abstract

Purpose

The aim was to investigate how structured assessment of physical function can be performed in people with musculoskeletal disorders in arm-shoulder-hand. Specifically, we aimed to determine:

• Which questionnaires are available for structured assessment of physical function in people with musculoskeletal disorders in arm-shoulder-hand?

• What aspects of physical function do those questionnaires measure?

• What are the psychometric properties of the questionnaires?

Materials and methods

By means of a systematic review, questionnaires and psychometric tests of those were identified. ICF was used to categorise the content of the questionnaires, and the COSMIN checklist was used to assess the psychometric evaluations.

Results

Nine questionnaires were identified. Most items focused on activities rather than functions. Commonly, a couple of psychometric measurements had been tested, most often reported being adequate. Only one questionnaire had been tested for all aspects. Variation in scope and insufficient reports regarding validity and reliability make comparisons and decisions on use difficult both in clinical practice and for research purposes.

Conclusions

The level of psychometric evaluation differs, and often only a few aspects of validity and reliability have been tested. The questionnaires address activity issues to a higher extent than function.

This review investigates the content and quality of nine ASH questionnaires.

The questionnaires addressed activity issues to a higher extent than function.

The level of psychometric testing of the questionnaires differed.

DASH, Quick-DASH, and SPADI were the questionnaires that were most often evaluated with various psychometric tests, and with adequate results.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Information about patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are often used to diagnose a patient’s health condition and to evaluate the effects of treatment, as they are tools that are both practical and economical to use for gathering the necessary information. Regarding PROMs used to evaluate symptoms related to musculoskeletal disorders (MSD), there is a variety of questionnaires available with different content and quality, which makes comparisons between findings difficult or impossible [Citation1]. This study is a part of a research project investigating questionnaires available to measure physical function in people with musculoskeletal disorders [Citation2,Citation3]. In the current study, we focus on questionnaires clinically used to measure physical function related to MSD in arm-shoulder-hand (ASH). Different terms are used to characterise MSD in ASH, as work-related upper limb- (WRUL), upper limb- (UL), and upper extremity- (UE) disorders. A characteristic is that the conditions can affect tendon, nerve, muscle, circulation, joint, or bursa in the shoulders, elbows, forearms, wrists, and hands, resulting in pain and functional impairment and that no specific medical diagnosis or pathology can be determined [Citation4]. A series of different questionnaires are used in clinical practice to assess symptoms related to the disorders and there is no consensus regarding the state of the art of measurement [Citation5]. The use of different questionnaires makes the comparison of the results between studies somewhat difficult since focus, content, and assessment criteria might differ in some respects [Citation5,Citation6].

Some previous reviews on ASH questionnaires have been reported [Citation7–11]. The included questionnaires in those reviews were not all PROMS and they focused on different areas. For example, were some physical tests were included among the questionnaires [Citation12–14]. Some of the reviewed questionnaires were surgery-related [Citation15] while others included questionnaires focused on a specific illness, e.g., osteoarthritis [Citation16], rotator cuff syndrome [Citation17], and shoulder instability [Citation18].

When looking into the methods and checklists that were used to estimate the quality of the included questionnaires, two of the identified previous reviews [Citation9,Citation10] were merely descriptive and no analysis or checklist for quality estimation was used. The three remaining reviews [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11] used different instruments for quality estimation. The first [Citation7] used the COnsensus‐based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments, the COSMIN checklist [Citation19]. The second [Citation8] used a checklist composed using parts of review criteria developed by the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcome Trust [Citation8,Citation20] and a checklist developed by Bombardier and Tugwell [Citation21]. The third review [Citation11] developed a checklist of quality criteria based on the above-described checklist by Bot et al. [Citation8] and quality criteria described by Finch et al. [Citation22].

Regarding the quality of the questionnaires, Alreni et al. [Citation7] found limited positive evidence of the validity of the DASH, and QuickDASH, as well as unknown evidence of responsiveness. They found no available data regarding the three measures of reliability for the questionnaires. Although they found that DASH and Quick-DASH had a limited amount of low-quality evidence, they found them to be promising measures although they required further evaluation. Bot et al. [Citation8] included the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), Disability Arm Shoulder Hand (DASH), Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ), Upper Extremity Functional Scale (UEFS), and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) in their review, among others. They concluded that none of the questionnaires had satisfactory results for all properties and that most studies had small sample sizes. Among the studied questionnaires, DASH and SPADI were most extensively tested and DASH had the best ratings regarding clinimetric properties. Roy et al. [Citation11] also included DASH and SPADI among others in their review. They summarise that all of the included questionnaires had excellent reliability measured by intraclass correlation (ICC), were strongly correlated and could differentiate between different populations and disability levels and that the psychometric properties thereby were acceptable for clinical use.

The three previously published reviews [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11] on ASH questionnaires did not include all the same questionnaires and presented different results. One of them found the psychometric properties of the included questionnaires acceptable for clinical use [Citation11]; the other that none of the questionnaires had satisfactory results for all properties, and that most studies had small sample sizes [Citation8]; while the third reported that some of the questionnaires had a limited amount of low-quality evidence, were promising measures although they required further evaluation [Citation7]. All three reviews focused on psychometric testing and did no analysis of what the included items actually measure.

When it comes to measurement of physical function for MSD in arm-shoulder-hand one can conclude that a lot of different questionnaires and tests are used, which may focus on different areas and different symptoms. Previous reviews show different results [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11] and a need for further studies on different psychometric properties has been addressed [Citation7,Citation8]. None of the identified previous reviews has taken into account the content of the questionnaires. The purpose of the present study was to provide information to ease the clinical choice of a suitable questionnaire in the diagnostic process and evaluation of treatment. Thus the current systematic review aimed to (i) identify structured assessment questionnaires assessing physical function in people with musculoskeletal disorders in arm-shoulder-hand; (ii) describe what aspects of physical function are measured, and (iii) describe the reported psychometric properties of the questionnaires.

Materials and methods

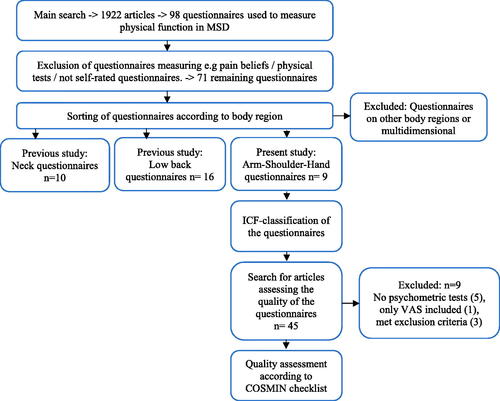

The current study was designed as a systematic literature review [Citation23,Citation24], comprising three phases. Phase 1, a systematic literature search for questionnaires to be included, was developed for structured assessment of function related to musculoskeletal disorder in arm-shoulder-hand. Phase 2, categorisation of item content in included questionnaires, and phase 3 determining measurements properties of the questionnaires ().

Phase 1: systematic literature search for questionnaires

The databases used were PubMed, Cinahl, Web of Science, and PsycInfo. Search terms () were identified according to the PICO model [Citation25], hence describing the population (P), intervention (I), and outcome (O). Comparison (C) was excluded since comparative studies were not in the scope of the current study. Initially, a broad search within the comprehensive research project was executed for articles reporting the development of systematic measures of physical function among people with musculoskeletal disorders. Excluded health conditions are described at the bottom of .

Table 1. Search terms used.

An updated focused search for articles reporting the use of arm-shoulder-hand questionnaires specifically was conducted, as some time had passed since the initial broad literature search in the larger multifactorial research project. The time frame was set to studies published until 18 September 2018 using slightly revised search terms ().

Phase 2: categorisation of item content using the ICF

To categorise the item content in the identified questionnaires, WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) [Citation26] was used. The ICF is widely used internationally in rehabilitation to characterise functional impairment caused by, e.g., musculoskeletal disorders. The classification builds on the biopsychosocial model, incorporating different perspectives on health and health-related conditions as the medical (body functions and body structures), and the social (in form of activities and participation). The definition of function and disability by WHO is: “the term functioning refers to all body functions, activities, and participation, while disability is similarly an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions” [Citation26], p. 2. To determine the focus of assessment and coverage of items, all items in the questionnaires were categorised using the whole hierarchical structure of the ICF [Citation26]. The categorisation of each item content was performed independently by both authors using the ICF classification on levels 2–5 and was followed by a comparative discussion to reach a consensus. Level 2 indicates chapters, e.g., d4 Mobility, and level 5, using four digits, e.g., d4302 Carrying in the arms. The categories “Other specified” or “unspecified” were not used. Initially, about 85% interrater reliability was achieved, and a full agreement was reached after mutual discussion.

Phase 3: determining measurements properties

Phase 3 included a systematic search, using the same databases as previously described, for articles reporting psychometric evaluation of the included arm-shoulder-hand questionnaires. Now, the search terms “validity OR reliability OR responsiveness AND name of questionnaire” were used. Selection of relevant articles was done by sifting through the title, abstract, and when necessary, the article text. Inclusion criteria were reports of psychometric tests of the original version of the questionnaires in the original language, so translated versions of the questionnaires were excluded as well as studies that met our previous criteria for exclusion (see ). During the process of analysis, repeated searches were performed to find any newly published studies, the last time 2 April 2020.

The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN checklist) was used, which provides a standardised set of criteria to determine which psychometric properties have been evaluated for an instrument, and to evaluate its validity and reliability [Citation19,Citation27–29].

It is suitable for the assessment of psychometric properties of questionnaires, as it contains standards for design and statistical methods to assess psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measurements. For further information regarding the COSMIN checklist see [Citation27], where definitions of relevant psychometric properties are to be found on p. 9. One of the authors and a statistician examined the psychometric properties, followed by a discussion to reach a consensus regarding the level of quality of the questionnaire. The measurement properties were rated as “adequate” or “not adequate” according to the guidelines in the COSMIN checklist [Citation27–30]. The rating not adequate indicated that the property was rated as “otherwise or cannot be determined.” The quality criteria and descriptions of the rating level adequate, are listed in .

Table 2. Adequate measurement properties for COSMIN checklist variables.

For criterion validity, only questionnaires (i.e., not single scales, such as visual analogue scales) were considered as criterion instruments. If an instrument (either evaluated instrument or criterion instrument) contained several scales, the overall methodological quality is determined by taking the lowest rating of any of the scales.

Results

Nine questionnaires developed for structural assessment of physical function among people with arm-shoulder-hand problems were identified [Citation31–39] (). The search for articles presenting psychometric testing of the questionnaires, whereof nine were excluded as the intended sample was not included, only VAS was investigated, or that no psychometric tests were performed. Thus, remaining for evaluation of psychometric testing were 36 articles [Citation34–43] ().

Table 3. Included arm-shoulder-hand questionnaires.

Questionnaire content

Eight of the questionnaires included items where several aspects of activity/participation were posed together in the same item and sometimes related to pain ( and , Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2). The UEFI included one aspect at a time, either regarding body function or activity/participation.

Table 4. Questionnaire content (No. of items).

Table 5. Prevalence of different aspects (ICF-codes) included in ASH questionnaires.

Some domains and areas in the ICF were included in more than half of the questionnaires. For body functions, it was, e.g., Mental function (b134 Sleep functions in six questionnaires) and Sensory functions and pain (b280 Sensation of pain in six questionnaires). For activity and participation it was seven aspects regarding Learning and applying knowledge (d170 Writing in five questionnaires), Mobility (d430 Lifting and carrying objects in nine questionnaires as well as d445 Hand and arm use in six questionnaires), Self-care (d540 Dressing in seven questionnaires, as well as d550, eating six questionnaires), Domestic life (d640 Doing housework in six questionnaires and Community, social, and civic life (d920 Recreation and leisure in six questionnaires).

Several more specific codes were frequently identified in the categorisation of item content (e.g., d430 Lifting and carrying objects, d4300 Lifting, d4400 Picking up, d449 Carrying, moving, and handling objects). However, the meaning was even more specific because the context or premises could differ between the separate items in the questionnaires.

Some questionnaire items were not possible to categorise according to the ICF classification, e.g., regarding sexual activity in DASH since the classification describes aspects of function but not activity. Other examples are the ability to do things over the head (ULFI/mod.ULFI), removing something from the back pocket (SPADI), doing things more often, as rub the shoulder (SDQ), rest, or use the other arm (ULFI/mod.ULFI). Further, items of a more general character, e.g., how well you are doing and your overall satisfaction (SRQ), was not possible to categorise according to the ICF.

Methodological quality

SPADI was evaluated in 15 studies, of which reported reliability measures in seven of them were rated being adequate regarding internal consistency, reliability, and measurement error ( and ). For validity measures, no adequate results were reported regarding content validity, but construct validity was reported in four studies and was here rated as adequate in three of them. Criterion validity was reported in 12 studies in relation to 18 other instruments, of which SIP and SDQ were used as a comparison twice. Here, criterion validity was rated as being adequate in 13 cases, where SDQ was used twice. Not adequate criterion validity was rated in seven of the cases, e.g., in relation to FABQ, SF-36, SSRS, CSQ, and SIP which was used twice. Responsiveness was rated as being adequate in 6 studies and inadequate in two. For interpretability, some aspects were reported in nine of the studies.

Table 6. Methodological quality of the included questionnaires.

Quick-DASH was evaluated in ten studies, and reports in five of them regarding reliability measurements were rated having adequate levels of internal consistency, reliability, as well as level of measurement error, apart from one study indicating a not adequate level of measurement error. Content and construct validity were rated to be adequate in one study and the criterion validity was adequate related to five other questionnaires but evaluated as inadequate in relation to one (PROMIS). Responsiveness was rated as adequate in four studies, and all aspects regarding interpretability were reported in two studies, while some were reported in five studies.

The DASH was evaluated in five studies and reported reliability measurements were rated as having adequate levels of internal consistency, reliability, as well as a level of measurement error. No results were reported for content and construct validity measures, but an adequate criterion validity was reported in relation to four other questionnaires, where SPADI was used twice. Adequate responsiveness was found in four studies, and all aspects of interpretability were reported in two of the studies and some aspects in two.

SDQ was evaluated in four studies whereof reliability measurements, reported in one study, was rated as having adequate internal consistency. Criterion validity tested in relation to SPADI and SRQ was rated as having adequate results and to EQ5D with an inadequate result. Responsiveness was tested in two of the studies with adequate results and in one with negative. Interpretability was presented for all aspects in three of the studies and some aspects in one of them.

UEFI was evaluated in four studies and reported reliability measurements of internal consistency and reliability was rated adequate and measurement error was adequate in some of them. Construct validity was found to be adequate in one study, while criterion validity was adequate related to PLS and UEFS, but correlational tests against PS, PL, and PIS described an inadequate level. Responsiveness was rated as being adequate in one study and inadequate in another one. Interpretability was presented for some aspects in three of the studies.

The ULFI was evaluated in four studies, two studies reported internal consistency and reliability measurements rated as adequate while adequate levels of measurement error were rated in three studies. Construct validity was rated to be adequate in one study, and criterion validity was adequate in relation to three other questionnaires. Responsiveness was rated adequate in one study and some aspects of interpretability were reported in all studies.

The SRQ was evaluated in two studies, where reported internal consistency and reliability were rated as being adequate in one of them. The reported criterion validity was rated as adequate in relation to three other ASH questionnaires, but inadequate in relation to EQ5D. Responsiveness was adequate in one study and some aspects of interpretability were presented in both studies.

UEFS was evaluated in two studies, where internal consistency in one study, and reliability and measurement error in the other, was rated as adequate. Adequate criterion validity was reported in relation to UEFI, while inadequate correlation levels were found in relation to PLS and PIS.

Psychometric properties of ULFI-Mod were tested in one study where internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, and construct validity were rated to be adequate and some aspects were presented for interpretability.

Discussion

Questionnaire content

Some dimensions of Body functions were included in the questionnaires. It was Mental functions as psychic stability, appetite, and sleep; Sensory functions and pain as pain and sensitivity to pressure; Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions as muscle power and stiffness. All included dimensions and codes for Body functions seem relevant vis-a-vis the target group and the intended assessment.

The most common dimensions of Activity and Participation included in the questionnaires were Mobility (17 codes), Domestic life (nine codes), and Self-care (six codes). The Mobility codes ranged from the fine motor ability as d440 Fine hand use, d4400 Picking up, and d4401 Grasping, to general mobility as d470 Using transportation, d475 Driving, and d4751 Driving motorized vehicles. Domestic life codes mostly considered housework as cleaning, washing, and preparing meals, while self-care codes were about basic self-care as washing, dressing, and eating. The remaining included dimensions were learning and applying knowledge, general tasks and demands, major life areas, community, social and civic life, while aspects of communication and interpersonal interactions and relationships were not included.

It was apparent from the result that items regarding Activity and Participation in the ICF were dominating in the questionnaires, not function per se, so the questionnaires are to some extent measuring physical function by proxy. Consequently, arm-shoulder-hand questionnaires measure physical function as such to a lesser degree than they measure consequences in the daily life of an affected function. However, maybe this is the feasible way to measure physical function via PROMS regarding activities, while physical function as such is better suited to be measured by health professionals via observation and physical examination. It is noteworthy that none of the previous reviews [Citation7–11] has investigated the content of the questionnaires the way we have. Further, the notion of defining the concept of physical function is stressed, since different definitions might influence the findings. Awareness of the identified differences in the evaluation and rehabilitation of MSD in ASH provides a possibility to enhance the precision in measurement and potentially the outcome of care.

Methodological quality

In the current study, SPADI and Quick-DASH, and DASH were the most often tested questionnaires regarding psychometric properties, which is in line with previous findings [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11]. SPADI, DASH, and Quick-DASH were also the questionnaires with the highest number of tests indicating an adequate level of methodological quality. However, psychometric properties were still missing for some aspects in the COSMIN checklist [Citation28–30]. For DASH, content and construct validity had not been evaluated, and for SPADI results regarding content, validity was lacking. In previous studies, construct convergent validity was established between the DASH and SPADI [Citation8], but another study reported a good or doubtful construct validity [Citation7]. Only Quick-DASH was tested for all psychometric aspects according to the COSMIN list.

As could be expected for adequate criterion validity measures, the results on all the tested questionnaires presented adequate results in comparison to similar questionnaires, but not for general questionnaires or questionnaires with a different focus. Further testing of the less well-tested questionnaires would contribute to the knowledge regarding the validity and reliability measures of the questionnaires since adequate levels for all psychometric properties were reported in merely a few studies.

Many of the studies included in this review had small sample sizes, a problem recognized in previous research [Citation8]. The study by Roach et al. [Citation34] included 37 men, and the study of Stratford et al. [Citation36] included 46 men and women. Some of the available tests are sensitive to small sample sizes and to do many hypothesis tests or conducting factor analysis, as, e.g., been conducted by Roach et al. [Citation34]. This may jeopardise the significance of the results. Among several rules of thumb presented for factor analyses, you can find subject-to-variable ratios of 4:1 or 5:1 or a sample size of 100 or 200 people [Citation44]. However, these ratio levels were not always met in the included studies. The importance of calculating and justifying the sample size is a topic that previously has been discussed in other reviews [Citation11].

Lack of heterogeneity of the sample and inclusion of transcultural adaptations of questionnaires are other issues that may affect the results as well as the interpretation of the methodological quality. The lack of heterogeneity in samples was noticed in many of the articles included in the current review. Examples of conditions included in the mixed samples were patients having undergone surgery [Citation45–49], having osteoarthritis [Citation35,Citation49,Citation50], and fracture [Citation49]. However, previous research has reported the strength in DASH and SPADI to be able to differentiate between different populations [Citation11].

Previous reviews have reported different results regarding psychometric evaluations. For example, Roy et al. [Citation11] reported DASH as having excellent reliability, while Alreni et al. [Citation7] reported that no data was to find on reliability measurements. A closer look at the included studies and their results show that the review by Roy et al. [Citation11] included a mixed sample including, e.g., studies with post-operative evaluation, translated versions of the questionnaire, and only evaluate ICC, while Alreni et al. [Citation7] seems to include only studies where the sample constituted of people with neck and upper-limb problems and evaluated all three aspects of reliability included in the COSMIN checklist [Citation28–30]. So when comparing the results of reviews of different questionnaires, it is important to consider which samples and tests the conclusions regarding psychometric quality rests upon.

Comparisons of the current results of quality assessments with that of previous reviews are not at all straightforward due to major differences in study designs. Of the five previous reviews identified [Citation7–11], only one used the COSMIN checklist [Citation7], and only two questionnaires here being investigated, DASH and Quick DASH, were included in the previous reviews as well. Further, there were also few similarities with previous reviews regarding the inclusion of studies. The current study included five studies investigating the DASH [Citation45,Citation51–54] and ten studies investigating the Quick-DASH [Citation32,Citation45,Citation49,Citation52,Citation53,Citation55–59], while Alreni et al. [Citation7] only presented results from two studies for DASH [Citation60,Citation61] and three for Quick-DASH [Citation55,Citation61,Citation62]. Only one study was used in both cases despite overlapping time frames. There are major differences despite many similarities between the search strategies, e.g., the inclusion of several databases (including PubMed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science), no conflicting time limit. However, the search terms used might have affected the number of studies identified as the majority of studies included here was published within the time frame of previous research. Looking at the results of the quality assessment, the study results also differed. The current study found adequate results in several studies for the different quality criteria regarding the DASH. However, previous findings reported assessment levels of “Unknown, due to poor methodological quality,” or “no information available” for all COSMIN criteria. Further testing of the less well-tested questionnaires would contribute to the knowledge regarding the validity and reliability of the questionnaires available for clinical use.

Method discussion

In the present review, we have used the COSMIN checklist [Citation28–30], with a complementary definition of concepts and acceptable levels of measures. The COSMIN checklist of standards for the evaluation of the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties is a thoroughly developed and evaluated tool developed by a large international workgroup using a Delphi method and a consensus procedure. However, due to a large variation in the use of concepts and alternate evaluative methods, there can be a problem registering some tests, since not all are included in the checklist. So, what the authors in the included studies claimed to have evaluated might not correspond with what had been tested according to the COSMIN checklist vocabulary.

The differences in vocabulary for various statistical tests, and the use of different methods to perform the tests, are challenging when estimating the psychometric quality of a questionnaire, and consequently, in conducting a literature review on the topic. The assessment of reported criterion validity and responsiveness measures was the most confusing since there sometimes was a mix-up between reliability and measurement error. Construct validity was another concept causing difficulties in the analyses.

Our analysis of the tests and results presented in the articles were assessed and interpreted using the Cosmin checklist and vocabulary. It is difficult to find a universal instrument for assessment, as the use of concepts differs and there are alternative choices of psychometric tests available. However, the use of the COSMIN checklist can be recommended for the structured assessment of measurement properties of instruments.

The quality of the ICF model has previously been tested with varying results in different groups; low reliability with the need for modification when used in geriatric care [Citation63], while the tests showed acceptable quality when tested among people with osteoarthritis [Citation64] and children with autism [Citation65]. In the present study, the ICF was considered useful for the categorisation of the item content in the questionnaires; it provided an overview of what was actually assessed. However, some difficulties with granularity and precision of terms were noticed regarding the categorization. It was not possible to categorise items including aspects like the ability to “lift arms over head” (DASH), or” do things at or above shoulder height” (ULFI), which seem relevant to include in arm–shoulder–hand questionnaires as a measure of function. Sexual activity was another aspect that could not be classified, as only sexual function was included in the ICF classification. For some items, there was ambiguity regarding how to classify, for example, the item “use a knife to cut food” (DASH). Is that to be classified as “preparing meals” (d630) or as “eating” (d550), both of which could comprise the item? The standardized expressions in the ICF regarding activities sometimes incorporate several sub-activities, which could be used in various contexts.

Additionally, some questionnaire items described different contextual examples in brackets (cleaning, lifting; ULFI, playing instrument or sport; DASH) which in turn indicates the use of different ICF codes. Such items might create ambiguity regarding what to respond to in the questionnaire, and ultimately when looking at the responses, what is actually measured., Some items in the questionnaires differentiated between lifting/carrying heavy and light weights but this level of differentiation was not possible to classify according to the ICF. Still, the use of the ICF as a classification scheme can be recommended and helped in this case to identify the distinction between function and activity in the questionnaire items.

Conclusion

The study shows that the ASH questionnaires address activity issues to a higher extent than function; most commonly items regarding mobility, domestic life, and self-care. However, this may be a feasible way to measure physical function via PROMS regarding activity, while physical function as such is better suited to be measured by health professionals via observation and physical examination [Citation5]. The level of psychometric testing of the questionnaires differed. DASH, Quick-DASH, and SPADI had the highest number in a total of tests with reported adequate results, while several of the other included questionnaires were sparsely tested. A different vocabulary and the use of methods to perform the tests are also challenging when estimating the quality of a questionnaire. Despite some difficulties in the categorization of questionnaire items using the ICF classification and also to register some psychometric tests using the COSMIN checklist, we recommend the use of both for evaluation of questionnaires.

Appendix_2_ICF_codes_with_explanations.docx

Download MS Word (14.6 KB)Appendix_1_ICF_classification_of_the_content.docx

Download MS Word (16.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Wiitavaara B, Bjorklund M, Brulin C, et al. How well do questionnaires on symptoms in neck-shoulder disorders capture the experiences of those who suffer from neck-shoulder disorders? A content analysis of questionnaires and interviews. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:30.

- Wiitavaara B, Heiden M. Content and psychometric evaluations of questionnaires for assessing physical function in people with neck disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(19):2227–2235.

- Wiitavaara B, Heiden M. Content and psychometric evaluations of questionnaires for assessing physical function in people with low back disorders. A systematic review of the literature. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(2):163–172.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Work-related neck and upper limb musculoskeletal disorders. Luxembourg: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; 1999.

- Taylor AM, Phillips K, Patel KV, et al. Assessment of physical function and participation in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(9):1836–1850.

- Gimeno-Santos E, Frei A, Dobbels F, et al. Validity of instruments to measure physical activity may be questionable due to a lack of conceptual frameworks: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:86.

- Alreni ASE, Harrop D, Lowe A, et al. Measures of upper limb function for people with neck pain. A systematic review of measurement and practical properties. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;29:155–163.

- Bot SD, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, et al. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):335–341.

- Desai AS, Dramis A, Hearnden AJ. Critical appraisal of subjective outcome measures used in the assessment of shoulder disability. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(1):9–13.

- Kirkley A, Griffin S, Dainty K. Scoring systems for the functional assessment of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):1109–1120.

- Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(5):623–632.

- Lippitt SB, Harryman DT, Matsen FA. A practical tool for evaluation of function: the simple shoulder test. In: Matsen FA, Fu FH, Hawkins RJ, editors. The shoulder: a balance of mobility and stability. Rosemont (IL): American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1993. p. 501–518.

- McLean SJ, Balassoubramanien T, Kulkarnai M, et al. Measuring upper limb disability in non-specific neck pain: a clinical performance measure. Int J Phys Ther Rehab. 2010;1:44–52.

- Lomond KV, Cote JN. Shoulder functional assessments in persons with chronic neck/shoulder pain and healthy subjects: Reliability and effects of movement repetition. Work. 2011;38:169–180.

- Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, et al. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(6):347–352.

- Lo IK, Griffin S, Kirkley A. The development of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: the Western Ontario osteoarthritis of the shoulder (WOOS) index. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(8):771–778.

- Hollinshead RM, Mohtadi NG, Vande Guchte RA, et al. Two 6-year follow-up studies of large and massive rotator cuff tears: comparison of outcome measures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):373–381.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The assessment of shoulder instability. The development and validation of a questionnaire. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(3):420–426.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–549.

- Lohr KN, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, et al. Evaluating quality-of-life and health status instruments: development of scientific review criteria. Clin Ther. 1996;18(5):979–992.

- Bombardier C, Tugwell P. Methodological considerations in functional assessment. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1987;14(Suppl 15):6–10.

- Finch E, Brooks D, Stratford PW, et al. Physical outcome measures: a guide to enhanced clinical decision making. Hamilton (ON); Baltimore (MD): BC Decker; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

- Fink A. Conducting research literature reviews. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications Inc; 2010.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443.

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Short version; 2001 [cited 2018 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. COSMIN checklist manual; 2012 [cited 2017 May 11]. Available from: http://www.cosmin.nl/images/upload/files/COSMIN%20checklist%20manual%20v9.pdf

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745.

- Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):651–657.

- Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C, et al. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The upper extremity collaborative group (UECG). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602–608.

- Beaton DE, Wright JG, Katz JN, et al. Development of the QuickDASH: comparison of three item-reduction approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1038–1046.

- van der Heijden GJ, Leffers P, Bouter LM. Shoulder disability questionnaire design and responsiveness of a functional status measure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(1):29–38.

- Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, et al. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4(4):143–149.

- L'Insalata JC, Warren RF, Cohen SB, et al. A self-administered questionnaire for assessment of symptoms and function of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(5):738–748.

- Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Stratford DM. Development and initial validation of the upper extremity functional index. Physiother Can. 2001;53:259–267.

- Pransky G, Feuerstein M, Himmelstein J, et al. Measuring functional outcomes in work-related upper extremity disorders. Development and validation of the upper extremity function scale. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39(12):1195–1202.

- Gabel CP, Michener LA, Burkett B, et al. The upper limb functional index: development and determination of reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Hand Ther. 2006;19(3):328–348; quiz 49.

- Gabel CP, Michener LA, Melloh M, et al. Modification of the upper limb functional index to a three-point response improves clinimetric properties. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(1):41–52.

- Riley SP, Cote MP, Swanson B, Tafuto V, et al. The shoulder pain and disability index: is it sensitive and responsive to immediate change? Manual Ther. 2015;20(3):494–498.

- Riley SP, Tafuto V, Cote M, et al. Reliability and relationship of the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire with the shoulder pain and disability index and numeric pain rating scale in patients with shoulder pain. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;35:464–470.

- Jerosch-Herold C, Chester R, Shepstone L, et al. An evaluation of the structural validity of the shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) using the Rasch model. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(2):389–400.

- Thoomes-de Graaf M, Scholten-Peeters W, Duijn E, et al. The responsiveness and interpretability of the shoulder pain and disability index. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(4):278–286.

- Streiner DL. Figuring out factors: the use and misuse of factor analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39(3):135–140.

- Angst F, Goldhahn J, Drerup S, et al. How sharp is the short QuickDASH? A refined content and validity analysis of the short form of the disabilities of the shoulder, arm and hand questionnaire in the strata of symptoms and function and specific joint conditions. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1043–1051.

- Beaton D, Richards RR. Assessing the reliability and responsiveness of 5 shoulder questionnaires. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(6):565–572.

- Chesworth BM, Hamilton CB, Walton DM, et al. Reliability and validity of two versions of the upper extremity functional index. Physiother Can. 2014;66(3):243–253.

- Cook KF, Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, et al. The measurement level and trait-specific reliability of 4 scales of shoulder functioning: an empiric investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(11):1558–1565.

- Dale LM, Strain-Riggs SR. Comparing responsiveness of the quick disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand and the upper limb functional index. Work. 2013;46(3):243–250.

- Beaton DE, Richards RR. Measuring function of the shoulder. A cross-sectional comparison of five questionnaires. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:882–890.

- Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14(2):128–146.

- Franchignoni F, Vercelli S, Giordano A, et al. Minimal clinically important difference of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure (DASH) and its shortened version (QuickDASH). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(1):30–39.

- Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44.

- Jester A, Harth A, Wind G, et al. Disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) questionnaire: Determining functional activity profiles in patients with upper extremity disorders. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30(1):23–28.

- Fan ZJ, Smith CK, Silverstein BA. Responsiveness of the QuickDASH and SF-12 in workers with neck or upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders: one-year follow-up. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):234–243.

- Stoop N, Menendez ME, Mellema JJ, et al. The PROMIS global health questionnaire correlates with the QuickDASH in patients with upper extremity illness. Hand. 2018;13(1):118–121.

- Chester R, Jerosch-Herold C, Lewis J, et al. The SPADI and QuickDASH are similarly responsive in patients undergoing physical therapy for shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(8):538–547.

- Gabel CP, Yelland M, Melloh M, et al. A modified QuickDASH-9 provides a valid outcome instrument for upper limb function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:161.

- Moradi A, Menendez ME, Kachooei AR, et al. Update of the quick DASH questionnaire to account for modern technology. Hand. 2016;11(4):403–409.

- Huisstede BM, Feleus A, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Is the disability of arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire (DASH) also valid and responsive in patients with neck complaints. Spine. 2009;34(4):E130–E138.

- Mehta S, Macdermid JC, Carlesso LC, et al. Concurrent validation of the DASH and the QuickDASH in comparison to neck-specific scales in patients with neck pain. Spine. 2010;35:2150–2156.

- Fan ZJ, Smith CK, Silverstein BA. Assessing validity of the QuickDASH and SF-12 as surveillance tools among workers with neck or upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. J Hand Ther. 2008;21(4):354–365.

- Okochi J, Utsunomiya S, Takahashi T. Health measurement using the ICF: test-retest reliability study of ICF codes and qualifiers in geriatric care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:46.

- Kurtaiş Y, Oztuna D, Küçükdeveci AA, et al. Reliability, construct validity and measurement potential of the ICF comprehensive core set for osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:255.

- Aljunied M, Frederickson N. Utility of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) for educational psychologists’ work. Educ Psychol Pract. 2014;30(4):380–392.

- Thoomes-de Graaf M, Scholten-Peeters W, Karel Y, et al. One question might be capable of replacing the shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) when measuring disability: a prospective cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(2):401–410.

- Hill CL, Lester S, Taylor AW, et al. Factor structure and validity of the shoulder pain and disability index in a population-based study of people with shoulder symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:8.

- MacDermid JC, Solomon P, Prkachin K. The shoulder pain and disability index demonstrates factor, construct and longitudinal validity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7(1):12.

- Heald SL, Riddle DL, Lamb RL. The shoulder pain and disability index: the construct validity and responsiveness of a region-specific disability measure. Phys Ther. 1997;77(10):1079–1089.

- Williams JW Jr., Holleman DR Jr., Simel DL. Measuring shoulder function with the shoulder pain and disability index. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(4):727–732.

- Paul A, Lewis M, Shadforth MF, et al. A comparison of four shoulder-specific questionnaires in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(10):1293–1299.

- de Winter AF, van der Heijden GJ, Scholten RJ, et al. The shoulder disability questionnaire differentiated well between high and low disability levels in patients in primary care, in a cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1156–1163.

- van der Windt DA, van der Heijden GJ, de Winter AF, et al. The responsiveness of the shoulder disability questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(2):82–87.

- Hamilton CB, Chesworth BM. A Rasch-validated version of the upper extremity functional index for interval-level measurement of upper extremity function. Phys Ther. 2013;93(11):1507–1519.

- Lehman LA, Sindhu BS, Shechtman O, et al. A comparison of the ability of two upper extremity assessments to measure change in function. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(1):31–40.