Abstract

Purpose

To explore the parental impact and experiences of caring for a child with Down’s arthritis (DA), an aggressive, erosive form of arthritis affecting children with Down syndrome.

Materials and methods

Ten mothers of children with DA were interviewed via telephone. Interviews were guided using a semi-structured non-directive topic guide and ranged from 17 to 242 minutes in duration. Interpretative phenomenological analysis was the method of analysis.

Results

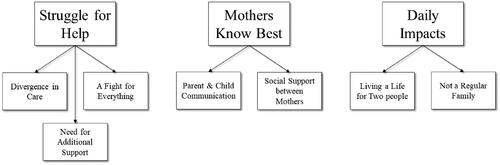

Three superordinate themes were identified: “Struggle for Help,” “Mothers Know Best,” and “Daily Impacts.” Common challenges included issues around child pain, communication, and challenges in accessing diagnoses and relevant healthcare services. Parents portrayed a reality characterised by ongoing struggles, particularly parents of nonverbal children and those living further from paediatric rheumatology services. Connecting with other parents of children with DA provided a vital source of emotional and informational support.

Conclusions

Findings provide novel insight into the experience of being mother of a child with DA, highlighting regional healthcare disparities, the need for upskilling of healthcare professionals, and for increased public awareness. Further research is needed to better understand the impact of DA on fathers and siblings. Findings can contribute to development and provision of supports to children with DA and their families.

Healthcare professionals need to be upskilled in the treatment of, and communication with, children with Down syndrome with chronic illnesses and their families.

A specialised stream of care for children with Down’s arthritis (DA) within paediatric rheumatology services may facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment and minimise risk of future complications.

Formalised support services for children with DA and their families are needed to minimise emotional distress.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an umbrella term used to describe chronic rheumatic diseases present with no other known cause in children under the age of 16 [Citation1]. It is relatively common, affecting approximately one in 1000 children in Europe [Citation2]. Delayed diagnosis, defined as three months from the onset of symptoms, is not uncommon in children with JIA, observed in an estimated 36% of cases [Citation3]. This delay in diagnosis and therefore treatment can have potentially detrimental consequences, including permanent disability resulting from irreversible joint damage, growth deformities, and loss of sight [Citation4].

Down syndrome (DS) is a lifelong chromosomal abnormality that affects an individual’s physical development while also causing learning difficulties. Down syndrome is one of the most common genetic causes of intellectual disability, accounting for approximately 15–20% of the intellectual disability population [Citation5]. It affects between one in 400–1500 babies born worldwide [Citation6]. In Ireland, the incidence of DS is estimated at one in 547, which is the highest rate in Europe [Citation7]. Children with DS are more likely to develop several other conditions, including leukaemia and other cancers, congenital heart disease, and Hirschsprung’s disease [Citation8]. However, arthritis among people with DS is largely underreported or recognised at onset [Citation4].

Down’s arthritis (DA), sometimes referred to as DS-associated arthritis, is a clinical term used to describe the co-occurrence of DS and arthritis. It is relatively common, with research reporting a shift in the estimated prevalence of DA from one in 1000 to 8.7–10.2 in 1000 [Citation9]. A recent Irish study [Citation4] reported that children with DS are at an increased risk of arthritis by 18–21 times relative to children without DS. The disease pattern appears unique to DA in that children frequently present with polyarticular arthritis where five or more joints are affected [Citation10]. As well as appearing to be a more aggressive and erosive disease than JIA, its treatment is complicated by a high percentage of drug-associated issues. Despite its prevalence, the unique challenges in its treatment, the developmental impact on the child, and the broader impacts on the family, research examining the co-occurrence of DS and arthritis to date is limited. There has been a recent increased emphasis on understanding DA from a biomedical perspective [Citation4]; however, hitherto there has been no published research exploring its impact from a psychological perspective. Research examining the emotional and psychological impacts of caring for a child with DA is therefore required.

Though no research has yet explored the impact of having a child with DA specifically, there is considerable evidence that having a child with either JIA or DS has significant impacts on the family. Being a parent to a child with DA is therefore likely to present a unique set of challenges. When asked about the impacts and experiences of being a parent of a child with JIA, parents describe this condition as being complicated, emotional, scary, multi-faceted, and isolating [Citation11]. They describe it as both a family and a community disease where communication and support are required. Similarly, caring for a child with chronic pain has a considerable impact on parents; many report a sense of burden, significant emotional distress, poorer family functioning, and financial hardship [Citation12–15]. In addition, in studies comparing families who have a child with DS to those without DS, parents of children with DS reported their families were just as cohesive and communicative as those without a child with a disability [Citation16], as well as having similar levels of confidence in their parenting abilities [Citation17]. However, their children tended to have more behavioural problems [Citation18]; a number of parents reported higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety [Citation19]; and some parents reported spending more time on caregiving activities [Citation20].

There is an important knowledge gap regarding the parental impacts of DA that needs to be addressed to advance research and practice in this area. This study therefore aimed to contribute to narrowing this knowledge gap by exploring the impacts and experiences of parents caring for a child with DA.

Methods

The Consolidated Criteria Reporting Qualitative Research Checklist (COREQ) [Citation21] for in-depth interviews and focus groups was used to ensure explicit and comprehensive reporting of this study (see Supplemental Appendix A).

Participants and recruitment

Parents of children with DA living in the Republic of Ireland were recruited online through social media platforms (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram). Interested parents contacted the researcher via phone or email and were provided with a detailed information sheet. Parents were eligible to take part if they were the parent of a child (i.e., under the age of 18) who had had a diagnosis of DA for a minimum of three months. Parents were also required to have significant daily contact with their child, to ensure they could report an accurate description of their day-to-day experiences. Parents who met the inclusion criteria were invited to partake. Mothers, fathers, and legal guardians were all eligible to participate; however, those who expressed interest (N = 12) were all mothers. Of these, one did not meet the inclusion criteria, and another withdrew due to a scheduling conflict. Therefore, a total of 10 mothers took part. provides demographic information about the participants and their children.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Study procedure

Non-directive, semi-structured interviews were conducted via phone to avoid the risk of COVID-19 transmission. This approach to qualitative interviewing was taken as it provided an appealing balance between structure and flexibility, and facilitated focused discussions regarding participants’ experiences of parenting a child with DA without strictly dictating the nature of the discussion. Parents were encouraged to lead the discussion, enabling exploration of topics not expressly listed in the interview schedule. The interview schedule was collaboratively developed by members of the research team (KMD and HD), with reference to previous research [Citation22]. Non-directive prompts were used to encourage parents to elaborate on topics of interest, enhancing the clarity and depth of the data. Field notes were taken during and after the interviews to ensure details not evident from the transcripts were not omitted. The lead researcher (KMD) kept a reflexive journal in which they recorded their evolving perceptions and personal introspections throughout the research process. This allowed the researcher to explicitly map their central role in the research process and created an audit trail of their insights to which they could refer during the analysis. Members of the research team (KMD and HD) met frequently during the data collection phase of the study to discuss how the interviews were progressing to further enhance reflexivity.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The average duration of the interviews was 77.2 minutes (range 17–242 minutes). In the interest of time, transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Participants were debriefed as to the purpose of the study at the end of the interview and were afforded the opportunity to ask any final questions. They were also given the option to follow up the researcher if any questions or concerns arose after the interview was terminated. There were no material incentives provided for participation in this study.

Qualitative analysis

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) is the qualitative analytical method employed in this study. The analysis was conducted according to the comprehensive description provided by Smith et al. [Citation23]. IPA is a well-suited method to the exploration of under-researched topics [Citation24], providing an inside view on the world in which participants are living [Citation25]. This method was also used in a similar study exploring the experiences of being a parent of an adolescent with complex chronic pain [Citation22], which further supports its suitability.

Following the transcription of interviews, the lead researcher (KMD) read through the transcripts multiple times to become familiar with the data before beginning the coding process. Transcripts were coded by KMD (20% double coded by HD) and themed individually and then combined to connect themes. Themes were then clustered and, finally, mastered into superordinate themes. The research team met frequently throughout the analysis process to discuss and refine evolving codes and themes. NVivo version 12 [Citation26] was used to facilitate the coding and analysis process. An experienced qualitative researcher (HD) oversaw all stages of the analysis to ensure the findings were coherent and that conclusions were grounded in the data. A final report of the study findings was circulated to all participants and an opportunity to discuss the findings with the research team was presented; however, given resource limitations in terms of time and funding, participants were not involved in the analysis.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the School of Psychology Research Ethics Committee at NUI Galway. Given that interviews were conducted via phone, all participants made an oral statement of informed consent to participate at the start of their interview, which was audio-recorded and stored in a secure repository separate from their interview recording/transcript to ensure their anonymity. Transcripts were anonymised to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of the interviewees. Data were curated and stored in a secure online Institutional repository that only the research team could access. This was in line with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Results

Analysis of the data resulted in three superordinate themes, which have been labelled “Struggle for Help,” “Mothers Know Best,” and “Daily Impacts.” All themes have sub-themes (see ), which we exemplify with verbatim quotations.

Struggle for help

This theme is comprised of three subthemes: “Divergence in Care,” “A Fight for Everything,” and “Need for Support.”

Divergence in care

Parents felt a divergence of care in three specified areas: the level of care available in Dublin relative to the rest of the country; the level of care given to children without DS as supposed to children with DA; and the level of care given to children who are verbal in comparison to those who are nonverbal.

The differential experiences of parents living in and around Dublin versus those in the rest of the country was reflected clearly in the interviews. The availability of healthcare services for children with DA varies considerably geographically, the implications of which were clear from the emotional tone of the interviews. The difficulty in accessing rheumatology services, as well as the time and financial cost of travelling to Dublin for multiple monthly appointments were clearly highlighted. In addition, the burden this posed to a young child with DA coupled with the challenges in organising care for other children was evident. All of these factors cumulatively represented a remarkable source of stress for parents. In comparison, parents living in the catchment area of Crumlin Children’s Hospital; although they experienced difficulties, they were relatively less stressed about accessing services due to fewer of these barriers being present.

All parents expressed frustration that, within the healthcare system, they felt that their children with DA were treated noticeably differently from children without DS living with chronic illnesses. They felt that healthcare professionals were not sufficiently trained as regards children with DA. In addition, parents strongly suggested that healthcare professionals had little experience in treating children with DA, which they felt required a particular set of skills and expertise. They felt that this resulted in their children receiving a lower level of care. Furthermore, parents described the limited access to services such as rehabilitation, hydrotherapy, or pain management for their children, relative to peers without a disability, as “unfair” (Blake) and “horrible” (Harriet).

Parents also described the search for a diagnosis for their children as particularly difficult. For example, the gold standard assessment for arthritis (i.e., magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) is often particularly stressful for children with DS, many of whom need a general anaesthetic to undergo the scan, resulting in many children being placed on a waiting list of up to two and a half years. This wait for the MRI and resultant delay in diagnosis, and therefore treatment, often results in irreversible damage to the joints. Parents struggled with frustration over this delay and were distressed and fearful of the possible physical damage that was occurring in the meantime. One parent described her DA experience as a “double blow” (Donna) from the child’s medical condition coupled with the perceived shortcomings in their care.

Kids with Down syndrome are overlooked […] they’re not getting treated and they’re not getting the same services as other kids. (Harriet)

It’s just, oh my god, it’s just…it’s just so frustrating that, you know, the Down syndrome would be… I don’t know?… the forgotten part of society… because I mean other, I’m sure other special conditions would feel the same, but we see other… others with special needs and they get everything thrown at them. (Anna)

Parents of children who were nonverbal relayed a more negative experience than parents whose children were verbal. They described feeling as though their child received a lower level of care, with one parent expressing with anger that nonverbal children were treated like “second class citizens” (Anna). They felt excluded from services such as pain management, believing the reason they could not access these vital services was that their child was nonverbal. A striking example described in several interviews related to children being repeatedly prescribed medications that they could not tolerate because they were unable to articulate their adverse effects. Parents became aware that their child could not tolerate the medication through observing dramatic changes in the child’s behaviour. One parent described her child as “a different boy” and “completely changed” as he was “curled up on a little ball on the couch… sucking his fingers, chewing his fingers, lashing out” (Anna). Another parent relayed her experience, saying she was “sick of telling them how sick he was” from the medication.

It’s actually unbelievable the disease like it’s really… it’s a horrible… debilitating disease… and for a child who’s nonverbal it’s so much worse because they don’t have a say. (Blake)

A fight for everything

Parents recounted a constant battle for everything (healthcare, resources, etc.) for their child, including supports to which they are legally entitled. The constant battling took a toll on parents, who described themselves as “so tired and weary from fighting” (Anna). The impact of this fight was apparent in the technical language some parents used in the interview, often neglecting to speak about their own experience and the effect it was having on themselves as individuals.

It’s the person that shouts the loudest that gets the most things. But you just get so tired and weary of just shouting and fighting for things constantly, because we have been fighting for things for the last 15 years. […] It’s always a fight. A fight for everything. Not just arthritis. It’s a fight for Down syndrome, […] for services, a fight for… information, a fight to be heard, a fight for… advice and help and tips and yeah, it is, it’s a fight for everything. (Anna)

Parents felt as though their child was considered less of a person than everyone else, as if they were somehow less entitled to help and support. Parents described being left with sole responsibility for doing everything for their child, placing considerable pressure on the parents. Responsibilities included but were not limited to being a carer for their child with additional needs, being a champion for their child, learning to do physiotherapy and occupational therapy exercises, along with advocating for more research. This caused some parents to feel, at times, “on the verge of a nervous breakdown” (Blake). This need to fight for their child was there from the very beginning; before receiving a diagnosis, parents struggled to be heard and not to be seen as “crazy” (Faye) when telling healthcare professionals that there was something wrong with her child.

Another struggle cited was the challenge in getting an accurate and full diagnosis. Some parents reported that doctors tended to attribute arthritis symptoms to the child’s DS without conducting a thorough investigation. Parents then felt that their concerns were not acknowledged. Some parents perceived doctors as condescending, not taking them or their child seriously, with one parent viewing the general practitioner (GP) as “their biggest hurdle” (Anna). Some parents felt that doctors were dismissive of their worries and attributed concerns to the parent’s psychological distress.

I found her [the GP] condescending on that occasion and she said to me ‘Blake, you seem not yourself, you’re, am… you know, have you got much help at home?’ and acting as if I was loopy… and I was like, this was like four weeks of this going on basically and I was like ‘No? He is not well? Nobody is listening to me.’ (Blake)

This evoked feelings of paranoia, anxiety, and frustration in parents. Parents were made to feel inferior as they were not medically trained, and as though they were searching for something to be wrong with their child. This raised concerns for parents about the possibility of being labelled “an overanxious mother” (Emma).

There was definitely pressure and distress and anxiety… and feelings of… paranoia I would say, oh you know, ‘Oh my god these people think… it’s me that has the issue and not the child.’ Then you go to the next level and say, ‘Jesus do they think that, you know, that I’m doing something to the child to leave her in this level of distress?’ (Emma)

Some parents recounted the fear they felt as they saw their child deteriorating quickly before their eyes before receiving a diagnosis. Some of these parents were afraid of the possibility of losing their child before they were diagnosed with DA. Some parents described feeling relieved when their child was diagnosed with DA as they finally had validation and confirmation that their concerns were genuine.

So for somebody to finally listen to me and tell me I wasn’t stark crazy, you know? It was relief, and then relief that it wasn’t all in my head. (Faye)

Definitely relief because as I say, we had gone from a position where we thought that our child was maybe going to… die. (Emma)

Parents spoke extensively about their fight to increase awareness of the condition. Parents felt that advocating for children with DA was particularly difficult given the invisible nature of the disease. They felt that most people do not recognise the debilitating effects of this chronic illness, with one parent admitting she had to change her own thinking and realise it is “not just a sore knee” (Anna). Parents also spoke with frustration and anger about organisations not recognising DA, the same organisations that they felt should be supporting their children. Parents felt that, due to this lack of awareness, the healthcare system was “prodding in the dark” (Emma), not knowing what to do with their children. Although parents acknowledged a lack of awareness regarding DA, some felt there was also an unwillingness to help, highlighting a perceived level of complacency among healthcare professionals when it came to treating their children. In discussing this lack of care, parental anger and fatigue was evident with the level of treatment afforded for their children, in some cases laughing with disbelief as they recalled their experiences.

[He was not being examined] literally because he has Down syndrome. […] I said, ‘I still want to know what’s wrong with him because maybe it will help us treat him,’… but they literally say, ‘Well, he has a diagnosis [of Down syndrome].’ (Blake)

Parents described a strong sense of responsibility for being their child’s voice and advocating for them to ensure they are not “left behind” (Emma). The importance of advocating for children with DA is something that some parents said they had learned from their experience, with the idea of fighting for your child and not relying on anyone else to do so being prevalent throughout the interviews.

The other thing that I would be saying as a parent to other parents is […] we advocate for them. We are their voices, whether they’re verbal or nonverbal. We are their advocates and… we need to advocate as strongly as possible because otherwise… we’d be left behind. They will be left to languish. (Emma)

Need for support

DS is characterised by several diverse features, including physical, neurological, sensory, cardiac, and gastrointestinal symptoms, which can present significant challenges to a child living with the condition. Similarly, juvenile arthritis presents unique challenges including living with chronic pain, stiffness, and fatigue, as well as a host of potential complications. Parents struggled to reconcile what a diagnosis of DA would mean for their child, in terms of the double-whammy of symptoms. One parent said the arthritis diagnosis had been “more distressing than anything else” (Emma). The way in which parents described their experiences varied from “devastating” (Donna) to “not as bad” (Jackie) as they had expected. However, it appeared that parents of children with fewer additional needs, those who were verbal with a greater level of independence, had more positive experiences. Coming to terms with the diagnosis was a significant emotional challenge for many parents. Others reported having to process feelings of guilt stemming from being unaware that their child was in pain, taking medication they did not tolerate, as well as fear about the future.

Ugh the guilt… and I still have the guilt. […] because [he] was nonverbal so he was never able to tell us what was wrong, but he was pointing to his wrists feeling sore, his ankles being sore. (Anna)

Parents described at length the various supports they wanted to see put in place for their children and their families. These included free counselling services to provide emotional support for parents, as they frequently recounted feelings of isolation accompanied by overwhelming responsibility. Given the limited availability of healthcare services, which necessitates parents providing vital therapies themselves, parents suggested practical supports such as home visits from physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Parents also expressed a need for reliable informational support; they felt that much of the information they had was obtained simply by chance, from other parents or through their own research. Parents communicated that advice and informational support from GPs and/or rheumatology teams is lacking, and that relevant information should be made available upon diagnosis. Furthermore, parents emphasised the need for better communication between primary care providers and paediatric rheumatology services in order for their children to receive adequate and appropriate ongoing care. They described the need for more social support from friends and family, such as simply asking how their child was or could they help in any way.

I just wish that people would see the same things that we see and would want to help, as much as we want to help. […] Because, you know, he goes through so much bad things anyway, it would be nice just to have a little bit of help, just to take some of the bad things away, and just to make things that little bit easier for him to manage, and just to make his life a little bit easier. (Blake)

Mothers know best

This theme is comprised of two subthemes: “Parent and Child Communication,” and “Social Support between Mothers.”

Parent and child communication

Communication difficulties between parent and child were discussed as a significant issue in most interviews, particularly in relation to the child’s pain communication. Some mothers spoke about how their child would not report their pain unless prompted, despite exhibiting pain behaviours (e.g., wincing, rubbing, and vocalisations). Some parents stated that their child “doesn’t realise the pain is not normal” (Claire) and may not have been communicating it for that reason. Attempting to teach their children that communication of pain can lead to solutions and relief from the pain was a task some parents took on. However, to most parents, pain communication remained a “puzzle” (Grace). This incognisance in relation to their child’s pain and diagnosis was present for many parents at the time of the interviews. Some felt that they are still “no wiser” (Donna) and cannot tell when or where their child is in pain, describing it as “guess work” (Blake). Parental distress was linked to uncertainty regarding their child’s diagnosis.

It’s very confusing, you know, as a mother you think you know your own child. […] When you’ve got… a very hidden… very aggressive thing like arthritis and a child that can’t verbalise it or doesn’t verbalise it… it’s very hard then to trust your own instinct. (Donna)

Looking back to before the diagnosis, some parents voiced that they were not shocked with the diagnosis and had, in some ways, “known for years” (Faye). However, while some parents had suspicions that their child had DA, others had no inclination. Though they believed that something was wrong with their child’s health, these parents did not expect it to be something as serious or chronic as DA. Some of the parents only had their child tested for DA because the test offered an opportunity to rule it out, or to ensure they would have no future regrets about not taking the test. One parent recalled feeling as though they were “wasting public resources” (Donna) by using this testing facility.

Communication between the parent and child posed as an issue in terms of receiving a diagnosis. Some parents did not think they would have gotten a referral or a diagnosis if they had attended a doctor without being armed with their own research. They advised other parents to do likewise when attending and not to accept “it’s just the Down syndrome” (Anna) as an answer. One parent also believed that healthcare professionals cited behavioural problems to avoid exploring other hypotheses or causes. Some parents learned from their experiences to insist and push for things with doctors and to always trust their gut instinct. In contrast, some parents learned to accept that they do not always know their child’s pain and put their trust in doctors to do the right thing in treating their child.

What I have learnt would be that mothers should always trust their gut instinct, okay? Nobody knows the child like the mother of the child, you know? (Isabelle)

Am trying to just to trust, I’m not one for blindly trusting in things but I kind of feel I have to. I have to believe that it’s working and that things are getting better because otherwise… I would go back into a depression about it. (Donna)

Social support between mothers

Some parents felt isolated in coping with their child’s DA, as many parents expressed that they were continuing to struggle to come to terms with the diagnosis. Although some parents spoke about receiving support from their husbands and families, many felt that their emotional needs differed from those of their male partners, who they felt took a more practical approach to coping with the diagnosis. Some felt that nobody else really understood the impacts of DA, including other family members. Several parents also stated that they would not discuss their child with parents of children without DS, believing that they would not understand or be able to provide emotional support. This perceived lack of understanding from others was attributed in part to the invisible nature of DA.

I think [friends and family] didn’t fully… understand, and I think maybe they still don’t. Maybe it’s a little bit of denial. I think they are still of the opinion that she looks fit and healthy, so she is fit and healthy. (Donna)

When feeling anxious, frustrated, isolated, upset, or in need of information, parents found solace in a closed Facebook support group for parents of children with DA, where they communicated with other mothers who understood their experiences. This group provided them with an invaluable source of comfort. Many parents labelled it as their main source of support, as well as a resource for finding out crucial information. It also helped them to put things into perspective. Parents recognised that every child with DA is different and that listening to other parents discuss their experiences could be frightening. However, this comradery helped parents feel as though they were not alone. This forum created a safe space, facilitating them to talk openly and honestly about their feelings, positive or negative, without judgement with others who truly understand. Some parents revealed that they would consult with other parents on this social forum even before consulting with healthcare professionals.

The issue of whether or not parents receive information from healthcare professionals surfaced more than once. This demonstrates the importance of parent-to-parent communication for them to remain informed. Some parents got their child tested for DA thanks to other parents advocating for it, highlighting the importance of parents being their own source of support and information, emotionally and medically.

It definitely helps to talk, you know? Like for me the support is other parents in the same situation… because there’s a huge comradery and empathy there and sympathy, you know, all round. […] And there is a very much a, kind of a… huge support, huge family there, you know? (Isabelle)

I definitely think parent to parent support is the best thing ever… learning from other people’s experiences. I think it’s just brilliant and… I think that’s vital. (Blake)

Daily impacts

This theme is comprised of two subthemes: “Living a Life for Two People,” and “Not a Regular Family.”

Living a life for two people

This title, a direct quote from a parent, encapsulates these parents’ lives, which are largely consumed by the impacts of their child’s DA.

You live in constant […] so I feel that I don’t live just my own life, I live a life for two people… because I have to interpret everything for her. […] It certainly consumes a large proportion of our life. (Emma)

Many parents spoke of the challenges of balancing employment and caring for a child with DA. They discussed having to use all their paid leave to take care of their child and to attend frequent appointments, expressing that “no employer would be okay with you taking all that time off” (Anna). Employment opportunities were impacted as parents felt they were left with the “burden of childcare” (Jackie) given the child’s diverse additional needs.

If I had three typically developing children, I would be happy with, you know, a nice lady who… is going to mind my children and keep them safe. But having a child who’s disabled, my needs are… I need somebody who is going to be a nice lady who will be nice to my children and keep them safe and also… help [child with DA] with his homework. And you know the nice lady down the road […] is not going to fit that bill for me. (Jackie)

Parents discussed a need to be “more alert with regard to [their child’s] health” (Claire) in day-to-day life. This is not only due to the invisible nature of the disease and the inability for many children with DS to communicate their pain; it was also due to the risk that COVID-19 posed to their children. At the time of the interviews, COVID-19 was rapidly spreading in communities and a nationwide lockdown was in effect. Children with DS already have compromised immunity due to their condition. In most cases, juvenile arthritis is treated with immunosuppressant medications, which places children with DA at even greater risk of contracting the virus. Concerned about the risk of COVID-19 infection for their child, some parents had made the decision to discontinue their immunosuppressant treatment, referring to it as a “catch-22” (Isabelle). Some parents felt that, in a way, they were already prepared for COVID-19, “already doing the extra hand washing and the alcohol gel and sterilising everything,” (Donna), while others were very worried about the vulnerability of their child.

Even in normal times we worry about [them] not being able to fight something as minor as a cold without it becoming more serious. Obviously, over the past few months we have been extremely worried about COVID-19. (Jackie)

Not a regular family

Having a child with DA impacts the entire family, limiting what they can and cannot do and where they can go as a family. The family must constantly think about whether the child with DA will be able to manage each activity. These challenges increase the stresses of the family. Parents described the impact on the siblings, with some parents admitting that siblings sometimes have to “take a back seat” (Anna) while the focus is on their child with DA. Mothers discussed how some siblings felt that the child with DA was favoured (e.g., “daddy’s favourite,” Jackie), whereas others experienced higher levels of anxiety as they worried about potential situations in relation to the child with DA. When the child with the condition is not well, it impacts the entire family.

It does affect our family life because [child] needs an awful lot of attention. And just if she’s not in form it affects everybody […] life can be very stressful. Very stressful at times like, d’ya know what I mean? Am, so it’s not, yeah it’s not normal. (Harriet)

One of the main challenges for some parents was keeping a “happy home for everyone” (Anna) and ensuring that everyone felt that their needs were being met. Parents were conscious to keep their other children informed regarding DA but were “mindful not to be burdening them” (Emma). In a lot of cases, there was one breadwinner and one carer in the family. This dynamic can have an adverse financial impact and in turn have a knock-on effect on marital relationships. Emotional impacts on parental relationships included some parents admitting to occasionally not sharing the hardships of their day in order not to worry their partner. In addition, some mothers found it difficult to confide in their partner due to their different outlooks on the situation.

On a personal level, between myself or my husband, you would be crashing things over in your own head but not maybe wanting to worry the other partner. […] It does put stress and pressure on relationships because… there was only one breadwinner so my poor husband was working ‘til the cows come home, and then he’d come home and maybe have to face into… whatever woes and worries were going on here in the day, so it definitely does have a negative impact. (Emma)

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the lived experiences of parents of children living with DA through qualitative interviews analysed using IPA. The analysis resulted in the construction of three main themes that captured these substantial impacts. The themes were “Struggle for Help,” “Mothers Know Best,” and “Daily Impacts.” Across these three themes, parents displayed an overall feeling of struggle, and a reality that was largely consumed by the needs of their child.

Communication about pain was an issue for all parents. Concerns over their child’s ability to communicate their pain resulted in distress, fear, and even devastation. Parents who believed that their child had a high pain threshold did not appear to be as distressed when discussing pain communication in comparison to parents who believed that their child did not have a high pain threshold but just could not communicate their pain. Parents’ difficulty in recognising the presence and location of the pain is not uncommon. Hennequin et al. [Citation27] indicate that 30% of parents of children with DS had difficulty in perceiving their child’s pain and 70% of parents had difficulty in identifying location of the pain. Having to depend on caregivers’ proxy reports of pain means that pain is often under-recognised and, therefore, undertreated [Citation28]. Davies [Citation29] reported that parents of children with DS recognise their child’s pain through verbalisations, behavioural expressions, and emotional changes, which were described in all interviews. However, as described by parents, constantly studying your child for these signs consumes a huge part of their lives, and in turn impacts other aspects.

All parents interviewed were mothers, and the majority were full-time carers whose partners were the breadwinners. Perceived differences in coping, whereby mothers felt their emotional coping style differed from their partners’ more practical approach, left some mothers feeling isolated. Differences between paternal and maternal coping styles are evident in the literature, with mothers being more likely to use emotional coping, whereas fathers prioritise cognitive coping strategies [Citation30]. This resulted in mothers seeking out peer support from other mothers through a closed Facebook group created by mothers specifically for parents of children with DA. Some felt that only other mothers of children with DA could truly understand what they were going through, with one parent describing the Facebook group as the only place she could go to discuss the hardships of the day. This highlights the need for greater awareness of the impacts of DA, as well as the need for more formal parental supports.

The nature of healthcare interactions had a considerable impact on parents’ experiences. Parental injustice appraisals were apparent in the data, whereby parents felt as though their psychological state was in question, rather than the health of their child. This induced stress and frustration in parents. Research has shown that higher levels of parental injustice appraisals are associated with increased parental stress and burden [Citation31]. This may hinder parents’ ability to effectively care for their child [Citation32], highlighting the importance of healthcare professionals listening to parents and taking their experiences and expertise on board. As one participant stated, “nobody knows our child to the extent that we do” (Emma). Although some parents spoke of their experience of being a parent of a child with DA as “not as bad” as they thought it would be, a picture of a life filled with a constant struggle, fear, and frustration dominated. Healthcare professionals attributing symptoms of arthritis to the child’s diagnosis of DS was frequently discussed as a source of distress. This further emphasises the need for upskilling of healthcare professionals in relation to the symptoms that present in children with DA. Furthermore, more research is needed to understand how to treat children with DA, as many parents felt the healthcare system was not adequately equipped given its unique disease pattern and the complications in its treatment.

Implications

Clinical implications

The current findings have several implications for clinical practice. First, results of this study highlight the importance of healthcare professionals viewing the parent as an informed participant in the treatment of their child and listening to and taking heed of the contextual information the parent provides. This would likely not only decrease the number of delayed diagnoses for children with DA, but would also reduce levels of parental distress when trying to find answers for their child. Second, findings suggest that increased awareness and recognition of DA as a unique condition among healthcare practitioners is needed. Indeed, current findings highlight the need for healthcare professionals to be upskilled in treatment of, and communication with, children with DS and their families in general. This is particularly pertinent given the long-term health implications of delayed diagnosis and access to appropriate medical care. These findings also highlight the need for a specialised stream of care within paediatric rheumatology services, and tailored support services for children and families to support the healthy development of the child.

Research implications

The current exploratory study illuminated further research questions that warrant investigation. Given that all participants in the current study were mothers, more research is needed to explore the impact of parenting a child with this condition on fathers. This is particularly pertinent given the potentially different primary coping styles of men and women. Similarly, research exploring the effect of DA on a child’s siblings is also warranted. Siblings are often neglected in the chronic illness and disability literature [Citation33,Citation34]; however, given the significant impacts on the family discussed by mothers in the current study, the experiences of siblings of children with DA must not be overlooked. Crucially, research exploring the lived experiences of children with DA themselves is needed. Though parents and siblings can provide important proxy information on the experience of DA, the voices of children living with DA must be heard to truly understand and address the impacts of this condition. There is a diversity of novel qualitative approaches (e.g., visual, creative, and play-based techniques) that may be used to allow children with DS with different levels of verbal ability to share their experiences and advance this under-researched area.

Second, parents in this study expressed the difficulty they had in recognising their child’s pain. Recognising pain in others is challenging, particularly in those who cannot communicate verbally [Citation35]. This means that pain in people with DS remains under-recognised and undertreated [Citation28,Citation36]. More research is needed into how these children communicate their pain through their behaviour, as well as how best to support parents to understand and recognise pain behaviours in their nonverbal children.

Finally, there have been no large-scale quantitative studies of psychological aspects of DA to date. The current findings reduce the knowledge gap and provide an important foundation for future quantitative research, as well as further qualitative research, to better understand the realities of living with a child with a diagnosis of DA.

Policy implications

According to the mothers we interviewed, a lack of awareness from both the public and healthcare professionals contributes to delayed diagnoses, irreversible joint damage, and lack of support and services available to children with DA. Efforts to increase public awareness of DA, for example, nationwide information campaigns, are therefore warranted. Additionally, results of this study support those of Butler et al. [Citation37] in that supporting parents to meet the emotional, physical, and financial challenges of being a caregiver is identified as a public health concern. The provision of programmes for parents of children with an intellectual disability and chronic pain should be a priority for practitioners and policymakers, with adequate funding provided to implement and evaluate these services. Parental engagement at such programmes could be considered in terms of change models [Citation38] in order to recognise the possible effects of a mandatory programme.

Strengths and limitations

The current study must be considered in light of certain limitations. First, carrying out interviews via phone due to COVID-19 restrictions may be considered a limitation. Historically, the use of telephones to conduct qualitative research has been considered inferior to face-to-face interviews for reasons including challenges in establishing rapport with the interviewee [Citation39] and the inability to identify and respond to visual cues [Citation40], leading to a possible negative impact on the richness and quality of the empirical data collected [Citation41]. However, telephone interviews offer certain advantages, including increased participation and access [Citation42] and increased interviewer safety [Citation43]. In addition, there is literature to suggest telephone interviews grant increased privacy to the interviewee [Citation44] and encourage reflexivity of the researcher [Citation40]. Despite the limitations, studies have supported the feasibility of obtaining rich, quality data from phone interviews [Citation45]. Second, as discussed above, all participants in the current study were mothers; this therefore limits the generalisability of findings to other kinds of caregivers, particularly fathers. More research exploring the experiences of other family members of children with DA is now needed.

Limitations notwithstanding, the current study offers important insights into the lived experience of parenting a child with DA, an area that has been hitherto understudied. This research boasts several important strengths. First, the sample size is a strength of this study as it captures the in-depth experiences of a relatively large number of participants from this unique population. Second, several steps were taken throughout the research process to ensure the study was rigorous in terms of its trustworthiness, credibility, dependability, and transferability. Finally, findings from this study not only support existing literature in the area of DS and chronic pain but raise additional important questions that provide scope for future research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study provides an in-depth analysis of the experience of being a parent to a child with DA. This study provides an important foundation for future clinical research and practice aimed at promoting awareness and understanding of the impact of a diagnosis of DA on the family. It stresses the need for greater medical training and upskilling of medical professionals on DA, as well as the development of psychological, emotional, and informational supports for parents and families of children with the condition.

COREQ__anon_.docx

Download MS Word (17.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

Data are not available due to ethical restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

References

- Giancane G, Consolaro A, Lanni S, et al. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(2):187–207.

- Hayward K, Wallace CA. Recent developments in anti-rheumatic drugs in pediatrics: treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):216.

- Ghazavi M. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective case-note analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(Suppl. 1):A36.

- Foley CM, Deely DA, MacDermott EJ, et al. Arthropathy of Down syndrome: an under-diagnosed inflammatory joint disease that warrants a name change. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000890.

- Karam SM, Riegel M, Segal SL, et al. Genetic causes of intellectual disability in a birth cohort: a population-based study. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167(6):1204–1214.

- Kazemi M, Salehi M, Kheirollahi M. Down syndrome: current status, challenges and future perspectives. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2016;5(3):125–133.

- Johnson Z, Lillis D, Delany V, et al. The epidemiology of Down syndrome in four counties in Ireland 1981–1990. J Public Health Med. 1996;18(1):78–86.

- Asim A, Kumar A, Muthuswamy S, et al. Down syndrome: an insight of the disease. J Biomed Sci. 2015;22(1):41–49.

- Juj H, Emery H. The arthropathy of Down syndrome: an underdiagnosed and under-recognized condition. J Pediatr. 2009;154(2):234–238.

- Foley CM, Killeen OG, Wilson G, et al. Down syndrome Ireland involved in life-changing research into arthritis. Down syndrome Ireland, Research into Arthritis in Children. Dublin (Ireland): Down Syndrome Ireland; 2017.

- Heath-Watson S, Sule S. Living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: parent and physician perspectives. Rheumatol Ther. 2018;5(1):1–4.

- Eccleston C, Crombez G, Scotford A, et al. Adolescent chronic pain: patterns and predictors of emotional distress in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents. Pain. 2004;108(3):221–229.

- Hunfeld JAM, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(3):145–153.

- Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, Stinson J, et al. Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1027–1038.

- Palermo TM. Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: a critical review of the literature. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21(1):58–69.

- Thomas V, Olson DH. Problem families and the circumplex model: observational assessment using the clinical rating scale (CRS). J Marit Fam Ther. 1993;19(2):159–175.

- Rodrigue JR, Morgan SB, Geffken GR. Psychosocial adaptation of fathers of children with autism, Down syndrome, and normal development. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22(2):249–263.

- Stores R, Stores G, Fellows B, et al. Daytime behaviour problems and maternal stress in children with Down's syndrome, their siblings, and non-intellectually disabled and other intellectually disabled peers. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998;42(Pt 3):228–237.

- Sanders JL, Morgan SB. Family stress and adjustment as perceived by parents of children with autism or Down syndrome: implications for intervention. Child Fam Behav Ther. 1997;19(4):15–32.

- Erickson M, Upshur CC. Caretaking burden and social support: comparison of mothers of infants with and without disabilities. Am J Ment Retard. 1989;94(3):250–258.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Jordan AL, Eccleston C, Osborn M. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(1):49–56.

- Smith JA, Jarman M, Osborn M. Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Murray M, Osborn M, editors. Qualitative health psychology: theories and methods. London (UK): Sage; 1999. p. 218–224.

- Smith JA. Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol Health. 1996;11(2):261–271.

- Conrad P. The experience of illness: recent and new directions. Res Sociol Health Care. 1987;6:1–31.

- International Q. NVivo qualitative data analysis software [software]; 1999. Available from: https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products

- Hennequin M, Faulks D, Allison PJ. Parents' ability to perceive pain experienced by their child with Down syndrome. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(4):347–353.

- McGuire BE, Daly P, Smyth F. Chronic pain in people with an intellectual disability: under-recognised and under-treated? J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54(3):240–245.

- Davies RB. Pain in children with Down syndrome: assessment and intervention by parents. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11(4):259–267.

- Barak-Levy Y, Atzaba-Poria N. Paternal versus maternal coping styles with child diagnosis of developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(6):2040–2046.

- Mohammadi S, de Boer MJ, Sanderman R, et al. Caregiving demands and caregivers’ psychological outcomes: the mediating role of perceived injustice. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(3):403–413.

- Baert F, McParland J, Miller MM, et al. Mothers' appraisals of injustice in the context of their child's chronic pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(10):1932–1945.

- Deavin A, Greasley P, Dixon C. Children’s perspectives on living with a sibling with a chronic illness. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20174151.

- Lamsal R, Ungar WJ. Impact of growing up with a sibling with a neurodevelopmental disorder on the quality of life of an unaffected sibling: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(4):586–594.

- Doody O, E. Bailey M. Pain and pain assessment in people with intellectual disability: issues and challenges in practice. Br J Learn Disabil. 2017;45(3):157–165.

- McGuire BE, Defrin R. Pain perception in people with Down syndrome: a synthesis of clinical and experimental research. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:194.

- Butler J, Gregg L, Calam R, et al. Parents' perceptions and experiences of parenting programmes: a systematic review and metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23(2):176–204.

- Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. Vol. 4. San Francisco (CA): Wiley; 2015. p. 125–148.

- Novick G. Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(4):391–398.

- Holt A. Using the telephone for narrative interviewing: a research note. Qual Res. 2010;10(1):113–121.

- Irvine A, Drew P, Sainsbury R. ‘Am I not answering your questions properly?’ Clarification, adequacy and responsiveness in semi-structured telephone and face-to-face interviews. Qual Res. 2013;13(1):87–106.

- Cachia M, Millward L. The telephone medium and semi‐structured interviews: a complementary fit. Qual Res Orgs Mgmt. 2011;6(3):265–277.

- Shuy RW. In-person vs. telephone interviews. In: Holstein JA, Guibrium JF, editors. Inside interviewing: new lenses, new concerns. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2003. p. 175–193.

- Carr ECJ, Worth A. The use of the telephone interview for research. Nurs Times Res. 2001;6(1):511–524.

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Salcedo B, et al. Conducting qualitative interviews by telephone: lessons learned from a study of alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Qual Soc Work. 2016;15(1):118–133.